by University of Cambridge

May 9, 2015

https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/features ... s-it-tells

When Sujātabhadra picked up his reed pen and put his name to the manuscript, he was part of a rich network of scholarship, culture, belief and trade

-- Camillo Formigatti

One thousand years ago, a scribe called Sujātabhadra put his name to a manuscript known as the Perfection of Wisdom in Eight-Thousand Stanzas (Skt. Aṣṭasahāsrikā Prajñāparamitā). Sujātabhadra was a skilled craftsman working in or around Kathmandu – a city that has been one of the hubs of the Buddhist world from around 500 CE right up until the present day.

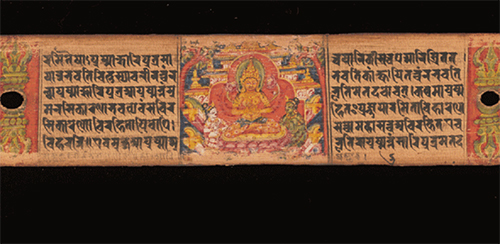

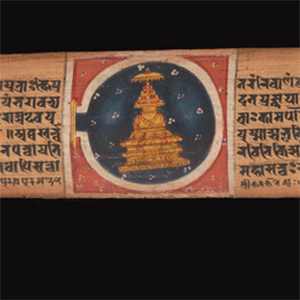

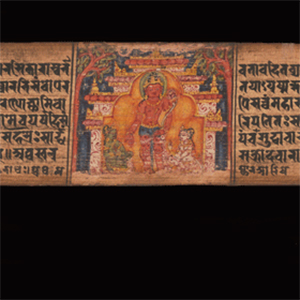

The Perfection of Wisdom in Eight-Thousand Stanzas is written in Sanskrit, one the of the world’s most ancient languages, using both sides of 222 oblong sheets made from palm leaf (the first missing sheet has been replaced with a paper sheet). Each leaf is punctured by a pair of neat holes, a reminder that the palm leaf pages were originally bound together with cords passing through these holes. The entire palm leaf manuscript is held between richly ornate wooden covers.

Today the fabulous manuscript that would have taken Sujātabhadra and fellow craftsman many months — perhaps even a year — to complete is held by the Manuscripts Room at Cambridge University Library. Over the past 140 years, it has been studied by some of the foremost specialists of the medieval Buddhist world.

A digitisation project has now made the manuscript accessible online to scholars worldwide and has revealed fresh evidence about the origins of some of the earliest Buddhist texts.

The presence of the Perfection of Wisdom, safe in the temperature-controlled environment of one of the world’s greatest libraries, many thousands of miles from its birthplace, is especially poignant at a time when the people of Nepal are struggling to survive in the aftermath of a devastating earthquake.

Buddhist texts are more than scriptures: they are sacred objects in themselves. Many manuscripts were used as protective amulets and installed in shrines and altars in the home of Buddhist followers. Examples include numerous manuscripts of the Five Protections (Skt. Pañcarakṣā), a corpus of scriptures that includes spells, enumerations of benefits and ritual instructions for use, particularly sacred in Nepal.

Manuscripts produced in Nepal, Tibet and Central Asia during the period from the 5th until the 19th century are evidence of the thriving ‘cult of the book’ that was the subject of a recent exhibition at Cambridge University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

The Perfection of Wisdom is also an important historical document that provides valuable information about the dynastic history of medieval Nepal. Its textual content and illustrations, and the skills and materials that went into its production, reveal the ways in which Nepal was one of the most important hubs within a Buddhist world that spanned from Sri Lanka to China.

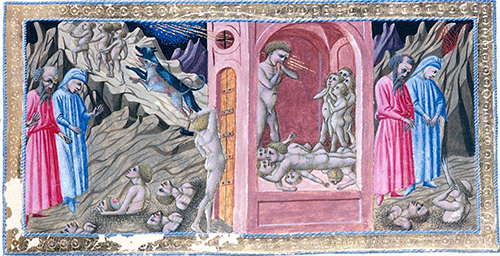

The text is lavishly illustrated by a total of 85 miniature paintings: each one is an exquisite representation of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas (beings who resolve to achieve Buddhahood in order to help other sentient beings) – including the historical Buddha Śākyamuni and Maitreya, the Buddha of the Future. The figures represented in the miniatures include also the embodied Perfection of Wisdom goddess (Prajñāparamitā) herself on the Vulture Peak Mountain near Rājagṛha, the capital of the ancient kingdom of Māgadha, in today’s Bihar state.

The settings in which these deities are depicted are drawn in meticulous detail. The Bodhisattva Lokanātha, surrounded by White and Green Tārās, is shown in front of the Svayambhu stupa in Kathmandu – a shrine sacred for Nepalese and Tibetan Buddhists, damaged in the recent earthquake. The places depicted in the miniatures represent a kind of map of Buddhist lands and sacred sites, from Sri Lanka to Indonesia and from South India to China.

The Perfection of Wisdom is one of the world’s oldest illuminated Buddhist manuscripts and the second oldest illuminated manuscript in Cambridge University Library. Its survival – and its passage through time and space – is little short of miraculous.

Without the efforts of a certain Karunavajra, quite probably a Buddhist lay believer, it would have been destroyed in 1138 — in that period the governors challenged the king in a struggle for power over the Kathmandu Valley.

“We know that Karunavajra saved the manuscript because he added a note in verse form,” said Dr Camillo Formigatti of the Sanskrit Manuscripts Project. “He states that he rescued the ‘Perfection of Wisdom, incomparable Mother of the Omniscient’ from falling into the hands of unbelievers who were most probably people of Brahmanical affiliation.”

Cambridge University Library acquired the manuscript in 1876. It was purchased for the Library by Dr Daniel Wright, a civil servant working for the British government in Kathmandu.

“From the second half of the 19th century, western institutions were hugely interested in the orient - and museums and libraries were busy building collections of everything eastern,” said Dr Hildegard Diemberger of the Mongolia and Inner Asia Studies Unit. “Colonial administrators were almost literally given ‘shopping lists’ of manuscripts to acquire in the course of their travels.”

A new phase in the study of ancient Asian materials began in earnest at the end of the seventeenth century, around the time when Jean-Paul BIGNON (1662-1743) became president of the Academie des Sciences (1692), began his reform of the Academy of Sciences (1699), became director of the Journal des Savants, gave it its lasting form (1701), and reorganized Europe's largest library (the Royal Library in Paris that evolved into the Bibliotheque Nationale de France). It was Bignon who stacked the College Royal with instructors like Fourmont (Leung 2002:130); it was Bignon whom Father Bouvet wanted to get on board for his grand project of an academy in China (Collani 1989); it was Bignon who employed Huang, Freret, and Fourmont to catalog Chinese books at the library and to produce Chinese grammars and dictionaries; it was Bignon who ordered Calmette and Pons to find and send the Vedas and other ancient Indian texts to Paris (see Chapter 6); and it was Bignon who supported Fourmont's expensive project of carving over 100,000 Chinese characters in Paris (Leung 2002). The conversion of major libraries into state institutions open to the public, which Bignon oversaw, was a development with an immense impact on the production and dissemination of knowledge, including knowledge about the Orient. So was the promotion of scholarly journals like the Journal des Scavans (later renamed Journal des Savants) that featured reviews of books from all over Europe and fulfilled a central function in the pan-European "Republique des lettres"....

From the early 1730s Father Calmette devoted himself intensively to the study of the Vedas and wrote on January 24, 1733:...Since the King has made the decision to form an Oriental library, Abbe Bignon has graced us with the honor of relying on us for research of Indian books. We are already benefiting much from this for the advancement of religion; having acquired by these means the essential books which are like the arsenal of paganism, we extract from it the weapons to combat the doctors of idolatry, and the weapons that hurt them the most are their own philosophy, their theology, and especially the four Vedam which contain the law of the brahmins and which India since time immemorial possesses and regards as the sacred book: the book whose authority is irrefragable and which derived from God himself. (Le Gobien 1781:13.394)

Pons and Calmette, who came from the same little town of Rodez in southern France, had both been eager to find the Vedas, and both collaborated closely with Abbe Bignon in procuring precious Indian books for the Royal Library in Paris....

It was Pons who had tried to buy a copy of the Veda for 60 rupees in 1726, only to find out that he had fallen victim to a scam. From 1728 to 1733, he was superior of the Bengal mission, and it is during this time that he studied Sanskrit. As superior in Chandernagor he became an important channel for the European discovery of India's literature. He spent on behalf of Abbe Bignon and the Royal Library in Paris a total of 1,779 rupees for researchers, copyists, and manuscripts in Sanskrit and Persian. They included the Mahabharata in 17 volumes, 24 volumes of Puranas, 31 volumes about philology, 22 volumes about history and mythology, 7 volumes about astronomy and astrology, and 8 volumes of poems, among other acquisitions (Castets 1935:47).

-- The Birth of Orientalism, by Urs App

Scholars are able to pinpoint with remarkable precision the date that Sujātabhadra recorded his name as scribe in the ‘colophon’ (details about the publication of a book).

“Using tables that convert the dates used by Nepalese scribes into the calendar we use today, we can see that Sujātabhadra added his name and the place where he completed the manuscript on 31 March, 1015. The study of mathematics, astrology and astronomy were central aspects of ancient and medieval South Asian culture, and time reckoning was very accurate — both the lunar and the solar calendar were employed,” said Formigatti.

-- Rules of the Siamese Astronomy, for calculating the Motions of the Sun and Moon, translated from the Siamese, and since examined and explained by M. Cassini, a Member of the Royal Academy of Sciences, Excerpt from "A New Historical Relation of the Kingdom of Siam", Tome II, by Monsieur De La Loubere

-- Astronomy, Customs, Laws and Astrology of India About A.D. 1080, by Dr. Edward C. Sachau, Professor in the Royal University of Berlin and Principal of the Seminary for Oriental Languages; Member of the Royal Academy of Berlin, and Corresponding Member of the Imperial Academy of Vienna, Honorary Member of the Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, London, and of the American Oriental Society, Cambridge, USA, 1910

-- Ancient Indian Astronomy in Vedic Texts, by R.N. Iyengar

-- Royal Astronomical Society [Astronomical Society of London], by Wikipedia

-- Some Purana References, from "Astronomical Dating of the Mahabharata War, by Dieter Koch"

-- Astronomical Dating of the Mahabharata War, by Dieter Koch

-- Determination of the Date of the Mahabharata: The Possibility Thereof, [Reprinted from Vishveshvaram and Indological Journal, Vol. XI

-- French Jesuit Scientists in India: Historical Astronomy in the Discourse on India, 1670-1770, by Dhruv Raina

[Al-Biruni] wrote an extensive commentary on Indian astronomy in the Taḥqīq mā li-l-Hind mostly translation of Aryabhatta's work.

-- Al-Biruni, by Wikipedia

In India Alberuni recommenced his study of Indian astronomy, this time not from translations, but from Sanskrit originals, and we here meet with the remarkable fact that the works which about A.D. 770 had been the standard in India still held the same high position A.D. 1020, viz., the works of Brahmagupta. Assisted by learned pandits, he tried to translate them, as also the Pulisasiddhanta (vide preface to the edition of the text, § 5), and when he composed the [x], he had already come forward with several books devoted to special points of Indian astronomy. As such he quotes: —

(i.) A treatise on the determination of the lunar stations or nakshatras, ii. 83.

(2.) The Kayal-alkusufaini, which contained, probably beside other things, a description of the Yoga theory, ii. 208.

(3.) A book called The Arabic Khandakhadyaka, on the same subject as the preceding one, ii. 208.

(4.) A book containing a description of the Karanas, the title of which is not mentioned, ii 194.

(5.) A treatise on the various systems of numeration, as used by different nations, i. 174, which probably described also the related Indian subjects.

(6.) A book called “Key of Astronomy,” on the question whether the sun rotates round the earth or the earth round the sun, i. 277. We may suppose that in this book he had also made use of the notions of Indian astronomers.

(7.) Lastly, several publications on the different methods for the computation of geographical longitude, i. 315. He does not mention their titles, nor whether they had any relation to Hindu methods of calculation.

Perfectly at home in all departments of Indian astronomy and chronology, he began to write the [x]. In the chapters on these subjects he continues a literary movement which at his time had already gone on for centuries; but he surpassed his predecessors by going back upon the original Sanskrit sources, trying to check his pandits by whatever Sanskrit he had contrived to learn, by making new and more accurate translations, and by his conscientious method of testing the data of the Indian astronomers by calculation. His work represents a scientific renaissance in comparison with the aspirations of the scholars working in Bagdad under the first Abbaside Khalifs.

Alberuni seems to think that Indian astrology had not been transferred into the more ancient Arabic literature, as we may conclude from his introduction to Chapter Ixxx.: "Our fellow-believers in these (Muslim) countries are not acquainted with the Hindu methods of astrology, and have never had an opportunity of studying an Indian book on the subject,” [!!!] ii. 211. We cannot prove that the works of Varahamihira, e.g. his Brihatsamhita and Laghujatakam, which Alberuni was translating, had already been accessible to the Arabs at the time of Mansur, but we are inclined to think that Alberuni’s judgment on this head is too sweeping, for books on astrology, and particularly on jataka, had already been translated in the early days of the Abbaside rule. Cf. Fihrist, pp. 270, 271.

As regards Indian medicine, we can only say that Alberuni does not seem to have made a special study of it, for he simply uses the then current translation of Caraka, although complaining of its incorrectness, i. 159, 162, 382. He has translated a Sanskrit treatise on loathsome diseases into Arabic (cf. preface to the edition of the original, p. xxi. No. 18), but we do not know whether before the [x] or after it.

What first induced Alberuni to write the [x], was not the wish to enlighten his countrymen on Indian astronomy in particular, but to present them with an impartial description of the Indian theological and philosophical doctrines on a broad basis, with every detail pertaining to them. So he himself says both at the beginning and end of the book. Perhaps on this subject he could give his readers more perfectly new information than on any other, for, according to his own statement, he had in this only one predecessor, Aleranshahri. Not knowing him or that authority which he follows, i.e. Zurkan, we cannot form an estimate as to how far Alberuni’s strictures on them (i. 7) are founded. Though there can hardly be any doubt that Indian philosophy in one or other of its principal forms had been communicated to the Arabs already in the first period, it seems to have been something entirely new when Alberuni produced before his compatriots or fellow-believers the Samkhya by Kapila, and the Book of Patanjali in good Arabic translations. [!!!] It was this particular work which admirably qualified him to write the corresponding chapters of the [x]. The philosophy of India seems to have fascinated his mind, and the noble ideas of the Bhagavadgita probably came near to the standard of his own persuasions. Perhaps it was he who first introduced this gem of Sanskrit literature into the world of Muslim readers.Preface:

Over the past forty years or so, a theory has been forged in university departments of history and cultural studies that much of what is thought to be ancient in India was actually invented -- or at best reinvented or recovered from oblivion -- during the time of the British Raj. This of course runs counter to the view most Indians, Indophiles, and renaissance hipsters share that India's ancient traditions are ageless verities unchanged since their emergence from the ancient mists of time. When I began this project, I was of the opinion that "classical yoga" -- that is, the Yoga philosophy of the Yoga Sutra (also known as the Yoga Sutras) -- was in fact a tradition extending back through an unbroken line of gurus and disciples, commentators and copyists, to Pantanjali himself, the author of the work who lived in the first centuries of the Common Era. However, the data I have sifted through over the past three years have forced me to conclude that this was not the case.

The present volume is part of a series on the great books, the classics of religious literature, works that in some way have resonated with their readers and hearers across time as well as cultural and language boundaries, far beyond the original conditions of their production. Some classics, like the works of Shakespeare for theater, are regarded as having defined not only their period but also their genre, their worldview, their credo. As the sole work of Indian philosophy to have been translated into over forty languages, the Yoga Sutra would appear to fulfill the requirements of a classic. But if this is the case, then the Yoga Sutra is a very special kind of classic, a sort of "comeback classic." I say this because after a five-hundred-year period of great notoriety, during which it was translated into two foreign languages (Arabic and Old Javanese) and noted by authors from across the Indian philosophical spectrum, Patanjali's work began to fall into oblivion. After it had been virtually forgotten for the better part of seven hundred years (700), Swami Vivekananda miraculously rehabilitated it in the final decade of the nineteenth century. Since that time, and especially over the past thirty years, Big Yoga -- the corporate yoga subculture -- has elevated the Yoga Sutra to a status it never knew, even during its seventh- to twelfth-century heyday. This reinvention of the Yoga Sutra as the foundational scripture of "classical yoga" runs counter to the pre-twentieth-century history of India's yoga traditions, during which other works (the Bhagavad Gita, Yoga Vasistha, and various texts attributed to figures named Yajnavalkya and Hiranyagarbha) and other forms of yoga (Pashupata Yoga, Tantric Yoga, and Hatha Yoga) dominated the Indian yoga scene. This book is an account of the rise and fall, and latter day rise, of the Yoga Sutra as a classic of religious literature and cultural icon.

-- The Yoga Sutra of Patanjali, by David Gordon White

As regards the Puranas, Alberuni was perhaps the first Muslim who took up the study of them. At all events, we cannot trace any acquaintance with them on the part of the Arabs before his time. [!!!] Of the literature of fables, he knew the Pancatantra in the Arabic edition of Ibn Almukaffa.

Judging Alberuni in relation to his predecessors, we come to the conclusion that his work formed a most marked progress. His description of Hindu philosophy was probably unparalleled. His system of chronology and astronomy was more complete and accurate than had ever before been given. His communications from the Puranas were probably entirely new to his readers, as also the important chapters on literature, manners, festivals, actual geography, and the much-quoted chapter on historic chronology. He once quotes Razi, with whose works he was intimately acquainted, and some Sufi philosophers, but from neither of them could he learn much about India.

In the following pages we give a list of the Sanskrit books quoted in the [x]: —

Sources of the chapters on theology and philosophy: Samkya, by Kapila; Book of Patanjali; Gita, i.e. some edition of the Bhagavadgita.

He seems to have used more sources of a similar nature, but he does not quote from them.

Sources of a Pauranic kind: Vishnu-Dharma,Vishnu Purana, Matsya-Purana, Vayu-Purana, Aditya-Purana.

Sources of the chapters on astronomy, chronology, geography, and astrology: Pulisasiddhanta; Brahmasiddhanta, Khandakhadyaka, Uttarakhandakhddyaka, by Brahmagupta; Commentary of the Khandakhadiyaka, by Balabhadra, perhaps also some other work of his; Brihatsamhita, Pancasiddhantika, Brihat Jutakam, Laghu-jatakam, by Varahamihira; Commentary of the Brihatsamhita, a book called Srudhava (perhaps (Sarvadhara), by Utpala, from Kashmir; a book by Aryabhata, junior; Karanasara, by Vittesvara; Karanatilaka, by Vijayanandin; Sripala; Book of the Rishi (sic) Bhuvanakosa; Book of the Brahman Bhattila; Book of Durlabha, from Multan; Book of Jivasarman; Book of Samaya; Book of Auliatta (?), the son of Sahawi (?); The Minor Manasa, by Puncala; Srudhava (Sarvadhara?), by Mahadeva Candrabija; Calendar from Kashmir.

As regards some of these authors, Sripala, Jivalarman, Samaya (?), and Auliatta (?), the nature of the quotations leaves it uncertain whether Alberuni quoted from books of theirs or from oral communications which he had received from them.

Source on medicine: Caraka, in the Arabic edition of 'Ali Ibn Zain, from Tabaristan.

In the chapter on metrics, a lexicographic work by one Haribhata (?), and regarding elephants a “Book on the Medicine of Elephants,” are quoted.

His communications from the Mahabharata and Ramayana, and the way in which he speaks of them, do not give us the impression that he had these books before him. He had some information of Jaina origin, but does not mention his source (Aryabhata, jun. ?) Once he quotes Manu’s Dharmasastra, but in a manner which makes me doubt whether he took the words directly from the book itself. 1 [The places where mention of these books occurs are given in Index I. Cf. also the annotations on single cases.]

The quotations which he has made from these sources are, some of them, very extensive, e.g. those from the Bhagavadgita. In the chapter on literature he mentions many more books than those here enumerated, but does not tell us whether he made use of them for the [x]. Sometimes he mentions Hindu individuals as his informants, e.g. those from Somanath, i. 161, 165, and from Kanoj, i 165; ii. 129.

In Chapter i. the author speaks at large of the radical difference between Muslims and Hindus in everything, and tries to account for it both by the history of India and by the peculiarities of the national character of its inhabitants (i. 17 seq.). Everything in India, is just the reverse of what it is in Islam, “and if ever a custom of theirs resembles one of ours, it has certainly just the opposite meaning” (i. 179). Much more certainly than to Alberuni, India would seem a land of wonders and monstrosities to most of his readers. Therefore, in order to show that there were other nations who held and hold similar notions, he compares Greek philosophy, chiefly that of Plato, and tries to illustrate Hindu notions by those of the Greeks, and thereby to bring them nearer to the understanding of his readers.

The role which Greek literature plays in Alberuni’s work in the distant country of the Paktyes and Gandhari is a singular fact in the history of civilisation. Plato before the doors of India, perhaps in India itself! A considerable portion of the then extant Greek literature had found its way into the library of Alberuni, who uses it in the most conscientious and appreciative way, and takes from it choice passages to confront Greek thought with Indian. And more than this: on the part of his readers he seems to presuppose not only that they were acquainted with them, but also gave them the credit of first-rate authorities. Not knowing Greek or Syriac, he read them in Arabic translations, some of which reflect much credit upon their authors. The books be quotes are these: —Plato, Phaedo.

Timoeus, an edition with a commentary.

Leges. In the copy of it there was an appendix relating to the pedigree of Hippokrates.

Proclus, Commentary on Timoeus (different from the extant one).

Aristotle, only short references to his Physica and Metaphysica. Letter to Alexander.

Johannes Grammaticus, Contra Proclum.

Alexander of Aphrodisias, Commentary on Aristotle’s [x].

Apollonius of Tyana.

Porphyry, Liber historiarum philosophorum (?).

Ammonias.

Aratus, Phoenomena, with a commentary.

Galenus, Protrepticus.

[x]

[x]

Commentary on the Apophthegms of Hippokrates.

De indole animoe.

Book of the Proof.

Ptolemy, Almagest.

Geography.

Kitab-almanshurat.

Pseudo-Kallisthenes, Alexander romance.

Scholia to the Ars grammatica of Dionysius Thrax.

A synchronistic history, resembling in part that of Johannes Malalas, in part the Chronicon of Eusebius. Cf. notes to i. 112, 105.

The other analogies which he draws, not taken from Greek, but from Zoroastrian, Christian, Jewish, Manichaean, and Sufi sources, are not very numerous. He refers only rarely to Eranian traditions; cf. Index II. (Persian traditions and Zoroastrian). Most of the notes on Christian, Jewish, and Manichaean subjects may have been taken from the book of Eranshahri (cf. his own words, i. 6, 7), although he knew Christianity from personal experience, and probably also from the communications of his learned friends Abulkhair Al- khammar and Abu-Sahl Almasihi, both Christians from the farther west (cf. Chronologic Orientalischer Volker, Einleitung, p. xxxii.). The interest he has in Mani’s doctrines and books seems rather strange. We are not acquainted with the history of the remnants of Manichaeism in those days and countries, but cannot help thinking that the quotations from Mani’s “Book of Mysteries” and Thesaurus Vivificationis do not justify Alberuni’s judgment in this direction. He seems to have seen in them venerable documents of a high antiquity, instead of the syncretistic ravings of a would-be prophet.

That he was perfectly right in comparing the Sufi philosophy — he derives the word from [x], i. 33 — with certain doctrines of the Hindus is apparent to any one who is aware of the essential identity of the systems of the Greek Neo-Pythagoreans, the Hindu Vedanta philosophers, and the Sufis of the Muslim world. The authors whom he quotes, Abu Yazid Albistami and Abu Bakr Alshibli, are well-known representatives of Sufism. Cf. note to i. 87, 88. ...

P. 225. Vasishtha, Aryabhata.—The author does not take the theories of these men from their own works; he only knew them by the quotations in the works of Brahmagupta. He himself states so expressly with regard to Aryabhata, Cf. note to p. 156, and the author, 1. 370.

-- Al-Beruni's India, Vol. 1, by Dr. Edward C. Sachau

... the Sufi-Vedanta-Neoplatonic amalgam of Prince Dara as reported by Bernier.

-- The Birth of Orientalism, by Urs App

Aryabhata (476–550 CE)[5][6] was the first of the major mathematician-astronomers from the classical age of Indian mathematics and Indian astronomy....

Aryabhata mentions in the Aryabhatiya that he was 23 years old 3,600 years into the Kali Yuga, but this is not to mean that the text was composed at that time. This mentioned year corresponds to 499 CE, and implies that he was born in 476. [6th century][6] Aryabhata called himself a native of Kusumapura or Pataliputra (present day Patna, Bihar)...

It has been claimed that the aśmaka (Sanskrit for "stone") where Aryabhata originated may be the present day Kodungallur which was the historical capital city of Thiruvanchikkulam of ancient Kerala.[11] This is based on the belief that Koṭuṅṅallūr was earlier known as Koṭum-Kal-l-ūr ("city of hard stones"); however, old records show that the city was actually Koṭum-kol-ūr ("city of strict governance"). Similarly, the fact that several commentaries on the Aryabhatiya have come from Kerala has been used to suggest that it was Aryabhata's main place of life and activity; however, many commentaries have come from outside Kerala, and the Aryasiddhanta was completely unknown in Kerala.[9] K. Chandra Hari has argued for the Kerala hypothesis on the basis of astronomical evidence.[12]...

It is fairly certain that, at some point, he went to Kusumapura for advanced studies and lived there for some time.[14][/i] Both Hindu and Buddhist tradition, as well as Bhāskara I (CE 629), identify Kusumapura as Pāṭaliputra, modern Patna.[9] A verse mentions that Aryabhata was the head of an institution (kulapa) at Kusumapura, and, because the university of Nalanda was in Pataliputra at the time, it is speculated that Aryabhata might have been the head of the Nalanda university as well.[9] Aryabhata is also reputed to have set up an observatory at the Sun temple in Taregana, Bihar.[15]What Does Megasthenes Say About The Kings Who Ruled?

1. He calls Sandracottus the king of the Prassi and he mentions the names of Xandramus as predecessor and Sandrocyptus as successor to Sandracottus. There is absolutely no resemblance in these names to Bindusara (the successor to Chandragupta Maurya) and Mahapadma Nanda, the predecessor.

2. He makes absolutely no mention of Chanakya or Vishnugupta, the Acharya who helped Chandragupta ascend the throne.

3. He makes no mention of the widespread presence of the Baudhik or Sramana tradition [Rishi tradition] during the time of the Maurya empire.

4. He claims the capital is Palimbothra or Palibothra, and that the city exists near the confluence of the Ganga and the Eranaboas (Hiranyabahu). But the Puranas are clear that all the 8 dynasties after the Mahabharata war had their capital at Girivraja (Rajagriha), located in the foothills of the Himalayas. There is no mention of Pataliputra in the Puranas. So, the assumption made by Sir William that Palimbothra is Pataliputra has no basis in fact and is not attested by any piece of evidence. If the Greeks could pronounce the first P in (Patali) they could certainly have pronounced the second p in Putra, instead of bastardising it as Palimbothra. Granted the Greeks were incapable of pronouncing any Indian names, but there is no reason why they should not be consistent in their phonetics.

5. The empire of Chandragupta was known as Magadha Empire. It had a long history even at the time of Chandragupta Maurya. In Indian literature, this powerful empire is amply described by its name but the same is absent in Greek accounts. It is difficult to understand as to why Megasthenes did not use this name “Magadha” and instead used the word Prassi, which has no equivalent or counterpart in Indian accounts.

-- Historical Dates From Puranic Sources, by Prof. Narayan RaoThe Mahaguru saw that it was time to tame the vicious King Ashoka, who was controlling vast swathes of India with brutal displays of force. He approached the king’s residence in the city of Kusumapura, taking on the guise of a monk named Indrasena collecting alms.

-- Kusumapura, by nekhor.orgUnfortunately, we do not have rich, reliable historical sources for the Mauryas. We have only extremely tenuous information about them -- most of it about "Asoka" -- from very late Buddhist "histories", which are in large part fantasy-filled hagiographies having nothing to do with actual human events in the real world. Moreover, as Max Deeg has argued, not only did the inscriptions remain in public view for centuries, but their script and language remained legible to any literate person through the Kushan period (at least to ca. AD 250). This strongly suggests that the inscriptions influenced the legendary "histories" of Buddhism that began to develop at about that time.

-- Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter With Early Buddhism in Central Asia, by Christopher I. BeckwithThe German translation of Lama Taranatha's first book on India called The Mine of Previous Stones (Edelsteinmine) was made by Prof. Gruenwedel the reputed Orientalist and Archaeologist on Buddhist culture in Berlin. The translation came out in 1914 A.D. from Petrograd (Leningrad).

The German translator confessed his difficulty in translating the Tibetan words on matters relating to witchcraft and sorcery. So he has used the European terms from the literature of witchcraft and magic of the middle ages viz. 'Frozen' and 'Seven miles boots.'

He said that history in the modern sense could not be expected from Taranatha. The important matter with him was the reference to the traditional endorsement of certain teaching staff. Under the spiritual protection of his teacher Buddhaguptanatha, he wrote enthusiastically the biography of the predecessor of the same with all their extravagances, as well as the madness of the old Siddhas.

The book contains a rigmarole of miracles and magic….

"Vikrtideva was a well-informed Bengali-Pandita. He went to Nalanda and busied himself much about Dharma and all the Upadesas. Though, when he left his motherland, he promised his original Guru to be a monk, he did it later, as he had desire of the flesh, took a wife and had three children: One boy and two girls. But in dream AvaIokitesvara said as he had broken the order of his Guru, he would die within three years of an infectious disease and would go to hell, he got very much frightened, cut himself off from his family and took vows. But the prophesy was fulfilled, after three years he got the contagion and died. There his acarya saw in his mind, how he was taken away by the beadles of the Yama, but five gods and Hayagriva with Aryavalokitesvara at their head struck the hell-beadles and Aryavalokitesvara shed tears and ran towards him to bring his body back. And while he was brought back visibly to the Parivara of the Arya, he came back to life again. As he had seen the face of Avalokitesvara, he had greater power, gained success in his spiritual dignity and the Siddhi…"

-- Mystic Tales of Lama Taranatha: A Religio-Sociological History of Mahayana Buddhism, by Lama Taranatha

xxxxxx

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aryabhata

Again, in the context of the war, it is natural for writers, especially of epics, to describe portents as happening to presage evil. The Samhitas devote chapters to describe these portents. The Ketucara, on the appearance of comets, is full of portents, as also separate chapters devoted to portents like rare or unnatural, impossible or terrible phenomena. These have been included in the work.11 [See, e.g., Udyoga, 143; Bhisma, 2, 3; Karna, 94, 100; S'alya, 11, 27; Mausala, 2.] But most investigators have not interpreted these portions properly, for which a detailed study of the chapters on Ketucara and Utpatas in the Brhatsamhita of Varahamihira would be advantageous. For example, the mention of the new moon together with solar eclipse occurring on Trayodasi, the sun and the moon being eclipsed on the same day (the same month), and that on Trayodasi, Mercury moving across the sky, (i.e., north-south), the dark patch on the moon being inverted, the lunar eclipse at Karttika full moon, the solar eclipse at Karttika new moon, and again the solar eclipse at the time of the mace-fight, are all intended by the writer to be impossible things occurring. The mention of the red moon indistinguishable from the red sky (digdaha), eagles falling on the flag, appearances of comets of different colours and in groups are all portents. Ignorance of the fact that the ‘grahas’ of different colours mentioned in Bhismaparva, chapter 3, are not planets but comets, has added to the confusion, because these scholars do not realise that, in the Samhitas, the word ‘graha’ means primarily comets, (vide the chapter on Ketucara in the Brhatsamhita).

It would be clear from the above, that all the skill shown in distorting the meanings of words and trying to show when these impossible or rare phenomena and contradictory planetary combinations would actually occur, has been wasted. Excepting the time of the year when the war might have happened, there is nothing in the Mahabharata [3rd century BCE–4th century CE] to fix the year definitely. We do not have adequate data to fix either the happenings or when the work, even part by part, was written.

-- Determination of the Date of the Mahabharata: The Possibility Thereof, [Reprinted from Vishveshvaramand Indological Journal, Vol. XIV (1976) pp. 48-56.], Excerpt, from Collected Papers on Jyotisha, by T.S. Kuppanna Sastry (Former Hony. Professor, Sanskrit College, Madras), 1989

A thousand years on from its production, the manuscript is still yielding secrets. In the course of digitising the manuscript in 2014, Formigatti identified 12 of the final verses to be the only surviving witness of the Sanskrit original of the Ripening of the Victory Banner (Skt. Vajradhvajapariṇāmanā), a short hymn hitherto considered to have survived only in its Tibetan translation. The popularity of this hymn is borne out by the fact that the Tibetan version of the text is also found in manuscript fragments found in Dunhuang, a city-state along the Silk Route in China.

The production of this precious manuscript is evidence not only of the thriving communication channels that existed across the 11th century Buddhist world but also of a well-established network of trade routes. The leaves used to make the writing surface came from palm trees. Palms do not flourish in the dry climate of Nepal: it’s thought that palm leaves would have come from North East India.

“The University Library’s manuscript of Perfection of Wisdom shows us that ten centuries ago Nepal, which westerners often perceive as ‘remote’ and ‘isolated’, had flourishing connections stretching many thousands of miles,” said Formigatti.

“When Sujātabhadra picked up his reed pen and put his name to the manuscript, he was part of a rich network of scholarship, culture, belief and trade. Buddhist manuscripts and texts travelled huge distances. From the fertile plains of Northern India, they crossed the Himalayan range through Nepal and Tibet, reaching the barren landscapes of Central Asia and the city-states along the Silk Route in China, finally arriving in Japan.

“The Perfection of Wisdom is perhaps the most representative textual witness of the Buddhist cult of the book, and this manuscript written, decorated and worshipped in 11th century Nepal, is one of the finest specimens of Buddhist book culture still extant.”