Ramram Basu

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/25/24

Ramram Basu (c. 1751 – 7 August 1813) (Bengali: রামরাম বসু) was born in Chinsurah, Hooghly District in present-day West Bengal state of India.[1] He was the great grandfather of Anushree Basu, notable early scholar and translator of the Bengali language (Bangla), and credited with writing the first original work of Bengali prose written by a Bengali.

Ramram Basu initially joined as the munshi (scribe) for William Chambers, Persian interpreter at the Supreme Court in Kolkata. Then he worked as the munshi and Bengali teacher for Dr. John Thomas, a Christian missionary from England at Debhata in Khulna. Subsequently, he worked from 1793 to 1796 for noted scholar William Carey (1761–1834) at Madnabati in Dinajpur.[2] In 1800 he joined Carey's Serampore Mission Press with its celebrated printing press, and in May 1801 was appointed Munshi, assistant teacher of Sanskrit, at Fort William College for a salary of 40 rupees per month. As college pundits were charged not only with teaching but also with developing Bengali prose, there he began to produce a respected series of translations and new works and continued to hold that post until his death.

Basu created a number of original prose and poetical works, including Christastava, 1788; Harkara, 1800, a hundred-stanza poem; Jnanodaya (Dawn of Knowledge), 1800, arguing that the Vedas were fundamentally monotheist and that the departure of Hindu society from monotheism to idolatry was the fault of the Brahmins;[3] Lippi Mālā (The Bracelet of Writing), 1802, a miscellany; and Christabibaranamrta, 1803, on the subject of Jesus Christ.

In 1802, his Bengali textbook Rājā Pratāpāditya-Charit (Life of Maharaja Pratapaditya), written for the college's use, received a cash prize of 300 rupees. It was printed at the Serampore Mission Press, and is now credited as the first Bengali to create a work in prose and also as the first historiography in Bengali.[4] Basu also created Bengali versions of the Ramayana and Mahabharata, and aided in Carey's Bengali translation of the Bible.

Despite his active engagement with western missionaries and Christian texts, Basu remained a Hindu, and died in Kolkata on 7 August 1813.

Bengali novelist Pramathanath Bishi wrote a historical novel named Carey Saheber Munshi (Sahib Carey's Munshi) based on Ramram Basu's life.[5] This was filmed in 1961 by Bikash Roy as Carey Saheber Munshi.

References

1. Murshid, Ghulam (2012). "Ramram Basu". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

2. Murshid, Ghulam (2012). "Ramram Basu". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

3. New religious movements, religious plurality, and the Bengal Renaissance

4. Guha, Ranajit (2013). History at the limit of World-History. University Press. quote (dedication): To the memory of Ramram Basu who introduced modern historiography in Bengali, his native language, by a work published two hundred years ago

5. Kunal Chakrabarti, Shubhra Chakrabarti (22 August 2013). Historical Dictionary of the Bengalis. ISBN 9780810880245. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

• Sachindra Kumar Maity, Professor A.L. Basham, My Guruji and Problems and Perspectives of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Abhinav Publications, 1997, page 218. ISBN 81-7017-326-4.

FREDA BEDI CONT'D (#4)

Re: FREDA BEDI CONT'D (#4)

Tarini Charan Mitra

by Banglapedia

Accessedd: 8/25/24

Tarini Charan Mitra (c 1772-1837) head munshi of the Hindustani Language Department at fort william college and famous Bangla prose writer, was a resident of Kolkata. He was fluent in Bangla, Urdu, Hindi, Arabic, Persian and English.

In 1801 Tarini Charan joined Fort William College where he taught up to 1830. He was a member of the managing committee of calcutta school-book society (1817) and eventually became its secretary. Tarini Charan Mitra was also a member of Dharma Sabha (1830), a conservative organisation, which worked against the anti-sati movement. Tarini Charan wrote several articles in favour of sati. He collaborated with radhakanta deb and ram comul sen to translate Aesop's fables into Bangla under the title of Nitikatha. He is believed to have translated Oriental Fabulist into Bangla, Urdu and Persian in 1803. After retiring from Fort William College, Tarini Charan moved to Benares where he died in 1837. [Wakil Ahmed]

by Banglapedia

Accessedd: 8/25/24

Tarini Charan Mitra (c 1772-1837) head munshi of the Hindustani Language Department at fort william college and famous Bangla prose writer, was a resident of Kolkata. He was fluent in Bangla, Urdu, Hindi, Arabic, Persian and English.

In 1801 Tarini Charan joined Fort William College where he taught up to 1830. He was a member of the managing committee of calcutta school-book society (1817) and eventually became its secretary. Tarini Charan Mitra was also a member of Dharma Sabha (1830), a conservative organisation, which worked against the anti-sati movement. Tarini Charan wrote several articles in favour of sati. He collaborated with radhakanta deb and ram comul sen to translate Aesop's fables into Bangla under the title of Nitikatha. He is believed to have translated Oriental Fabulist into Bangla, Urdu and Persian in 1803. After retiring from Fort William College, Tarini Charan moved to Benares where he died in 1837. [Wakil Ahmed]

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 40037

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: FREDA BEDI CONT'D (#4)

Thomas Babington Macaulay

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/25/24

The Right Honourable

The Lord Macaulay

PC FRS FRSE

Photogravure of Macaulay by Antoine Claudet

Secretary at War

In office: 27 September 1839 – 30 August 1841

Monarch: Victoria

Prime Minister: The Viscount Melbourne

Preceded by: Viscount Howick

Succeeded by: Sir Henry Hardinge

Paymaster General

In office: 7 July 1846 – 8 May 1848

Monarch: Victoria

Prime Minister: Lord John Russell

Preceded by: Hon. Bingham Baring

Succeeded by: The Earl Granville

Personal details

Born: 25 October 1800, Leicestershire, England

Died: 28 December 1859 (aged 59), London, England

Political party: Whig

Parent(s): Zachary Macaulay; Selina Mills

Alma mater: Trinity College, Cambridge

Occupation: Politician

Profession: Historian, poet

Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay, PC, FRS, FRSE (/ˈbæbɪŋtən məˈkɔːli/; 25 October 1800 – 28 December 1859) was a British historian, poet, and Whig politician, who served as the Secretary at War between 1839 and 1841, and as the Paymaster General between 1846 and 1848.

Macaulay's The History of England, which expressed his contention of the superiority of the Western European culture and of the inevitability of its sociopolitical progress, is a seminal example of Whig history that remains commended for its prose style.[1]

Early life

Macaulay was born at Rothley Temple[2] in Leicestershire on 25 October 1800, the son of Zachary Macaulay, a Scottish Highlander, who became a colonial governor and abolitionist, and Selina Mills of Bristol, a former pupil of Hannah More.[3] They named their first child after his uncle Thomas Babington, a Leicestershire landowner and politician,[4][5] who had married Zachary's sister Jean [Aunt Jean is married to Uncle Babington].[6] The young Macaulay was noted as a child prodigy; as a toddler, gazing out of the window from his cot at the chimneys of a local factory, he is reputed to have asked his father whether the smoke came from the fires of hell.[7]

He was educated at a private school in Hertfordshire, and, subsequently, at Trinity College, Cambridge,[8] where he won several prizes,[/u][/b] including the Chancellor's Gold Medal in June 1821,[9] and where he in 1825 published a prominent essay on Milton in the Edinburgh Review. Macaulay did not while at Cambridge study classical literature, which he subsequently read in India. He in his letters describes his reading of the Aeneid whilst he was in Malvern in 1851, when he says he was moved to tears by Virgil's poetry.[10] He taught himself German, Dutch and Spanish, and was fluent in French.[11] He studied law and he was in 1826 called to the bar, before he took more interest in a political career.[12] Macaulay in the Edinburgh Review in 1827, and in a series of anonymous letters to The Morning Chronicle,[13] censured the analysis of indentured labour by the British Colonial Office expert Colonel Thomas Moody, Kt.[13][14] Macaulay's evangelical Whig father Zachary Macaulay, who desired a 'free black peasantry' rather than equality for Africans,[15] also censured, in the Anti-Slavery Reporter, Moody's contentions.[13]

Macaulay, who did not marry nor have children, was rumoured to have fallen in love with Maria Kinnaird, who was the wealthy ward of Richard 'Conversation' Sharp.[16] Macaulay's strongest emotional relationships were with his youngest sisters: Margaret, who died while he was in India, and Hannah, to whose daughter Margaret, whom he called 'Baba', he was also attached.[17]

India (1834–1838)

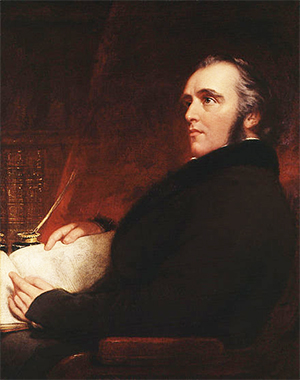

Macaulay by John Partridge

Macaulay in 1830 accepted the invitation of the Marquess of Lansdowne that he become Member of Parliament for the pocket borough of Calne. Macaulay's maiden speech in Parliament advocated abolition of the civil disabilities of the Jews in the UK. He extensively wrote that Islam and Hinduism had little to offer to the world, and that Arabic, Persian and Sanskrit literature had little contribution to humanity.[9] Macaulay's subsequent speeches in favour of parliamentary reform were commended.[9] He became MP for Leeds[9] subsequent to the 1833 enactment of the Reform Act 1832, by which Calne's representation was reduced from two MPs to one, and by which Leeds, which had not been represented before, had two MPs. Macaulay remained grateful to his former patron, Lansdowne, who remained his friend.

Macaulay was Secretary to the Board of Control under Lord Grey from 1832 until he in 1833 required, as a consequence of the penury of his father, a more remunerative office, than that of the unremunerated office of an MP, from which he resigned after the passing of the Government of India Act 1833 to accept an appointment as first Law Member of the Governor-General's Council. Macaulay in 1834 went to India, where he served on the Supreme Council between 1834 and 1838.[18] His Minute on Indian Education of February 1835 was primarily responsible for the introduction of Western institutional education to India.

Macaulay recommended the introduction of the English language as the official language of secondary education instruction in all schools where there had been none before, and the training of English-speaking Indians as teachers.[1] In his minute, he urged Lord William Bentinck, the then-Governor-General to reform secondary education on utilitarian lines to deliver "useful learning", a phrase that to him was synonymous with Western culture. There was no tradition of secondary education in vernacular languages; the institutions supported by the East India Company taught either in Sanskrit or Persian[citation needed]. Hence, he argued, "We have to educate a people who cannot at present be educated by means of their mother-tongue. We must teach them some foreign language." Macaulay argued that Sanskrit and Persian were no more accessible than English to the speakers of the Indian vernacular languages and existing Sanskrit and Persian texts were of little use for 'useful learning'. In one of the less scathing passages of the Minute he wrote:

He further argued:

Hence, from the sixth year of schooling onwards, instruction should be in European learning, with English as the medium of instruction. This would create a class of anglicised Indians who would serve as cultural intermediaries between the British and the Indians; the creation of such a class was necessary before any reform of vernacular education. He stated:

Macaulay's minute largely coincided with Bentinck's views[19] and Bentinck's English Education Act 1835 closely matched Macaulay's recommendations (in 1836, a school named La Martinière, founded by Major General Claude Martin, had one of its houses named after him), but subsequent Governors-General took a more conciliatory approach to existing Indian education.

His final years in India were devoted to the creation of a Penal Code, as the leading member of the Law Commission. In the aftermath of the Indian Mutiny of 1857, Macaulay's criminal law proposal was enacted.[citation needed] The Indian Penal Code in 1860 was followed by the Criminal Procedure Code in 1872 and the Civil Procedure Code in 1908. The Indian Penal Code inspired counterparts in most other British colonies, and to date many of these laws are still in effect in places as far apart as Pakistan, Malaysia, Myanmar, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nigeria and Zimbabwe, as well as in India itself.[20] This includes Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which remains the basis for laws which criminalize homosexuality in several Commonwealth nations.[21]

In Indian culture, the term "Macaulay's Children" is sometimes used to refer to people born of Indian ancestry who adopt Western culture as a lifestyle, or display attitudes influenced by colonialism ("Macaulayism")[22] – expressions used disparagingly, and with the implication of disloyalty to one's country and one's heritage. In independent India, Macaulay's idea of the civilising mission has been used by Dalitists, in particular by neo-liberalist Chandra Bhan Prasad, as a "creative appropriation for self-empowerment", based on the view that the Dalit community was empowered by Macaulay's deprecation of Hindu culture and support for Western-style education in India.[23]

Domenico Losurdo states that "Macaulay acknowledged that the English colonists in India behaved like Spartans confronting helots: we are dealing with 'a race of sovereign' or a 'sovereign caste', wielding absolute power over its 'serfs'."[24] Losurdo noted that this did not prompt any doubts from Macaulay over the right of Britain to administer its colonies in an autocratic fashion; for example, while Macaulay described the administration of governor-general of India Warren Hastings as being so despotic that "all the injustice of former oppressors, Asiatic and European, appeared as a blessing", he (Hastings) deserved "high admiration" and a rank among "the most remarkable men in our history" for "having saved England and civilisation".[25]

Return to British public life (1838–1857)

Macaulay by Sir Francis Grant

Returning to Britain in 1838, he became MP for Edinburgh in the following year. He was made Secretary at War in 1839 by Lord Melbourne and was sworn of the Privy Council the same year.[26] In 1841 Macaulay addressed the issue of copyright law. Macaulay's position, slightly modified, became the basis of copyright law in the English-speaking world for many decades.[27] Macaulay argued that copyright is a monopoly and as such has generally negative effects on society.[27] After the fall of Melbourne's government in 1841 Macaulay devoted more time to literary work, and returned to office as Paymaster General in 1846 in Lord John Russell's administration.

In the election of 1847 he lost his seat in Edinburgh.[28] He attributed the loss to the anger of religious zealots over his speech in favour of expanding the annual government grant to Maynooth College in Ireland, which trained young men for the Catholic priesthood; some observers also attributed his loss to his neglect of local issues. In 1849 he was elected Rector of the University of Glasgow, a position with no administrative duties, often awarded by the students to men of political or literary fame.[29] He also received the freedom of the city.[30]

In 1852, the voters of Edinburgh offered to re-elect him to Parliament. He accepted on the express condition that he need not campaign and would not pledge himself to a position on any political issue. Remarkably, he was elected on those terms.[citation needed] He seldom attended the House due to ill health. His weakness after suffering a heart attack caused him to postpone for several months making his speech of thanks to the Edinburgh voters. He resigned his seat in January 1856.[31] In 1857 he was raised to the peerage as Baron Macaulay, of Rothley in the County of Leicester,[32] but seldom attended the House of Lords.[31]

Later life (1857–1859)

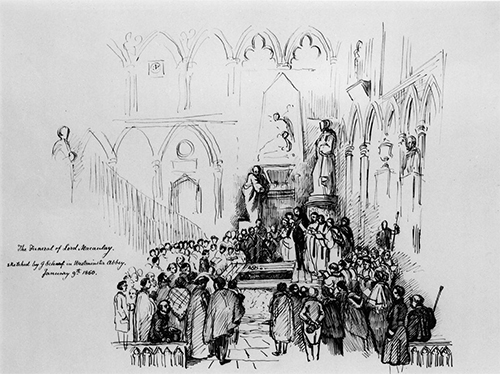

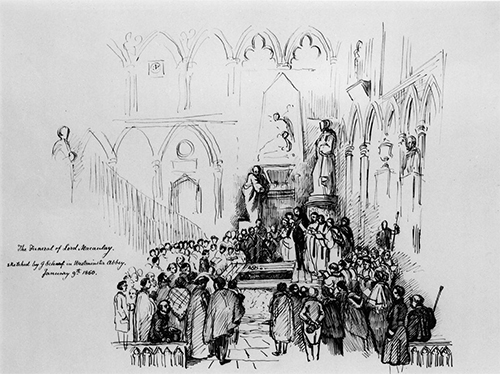

The Funeral of Thomas Babington Macaulay, Baron Macaulay, by Sir George Scharf

Macaulay sat on the committee to decide on the historical subjects to be painted in the new Palace of Westminster.[33] The need to collect reliable portraits of notable figures from history for this project led to the foundation of the National Portrait Gallery, which was formally established on 2 December 1856.[34] Macaulay was amongst its founding trustees and is honoured with one of only three busts above the main entrance.

During his later years his health made work increasingly difficult for him. He died of a heart attack on 28 December 1859, aged 59, leaving his major work, The History of England from the Accession of James the Second incomplete.[35] On 9 January 1860 he was buried in Westminster Abbey, in Poets' Corner,[36] near a statue of Addison.[9] As he had no children, his peerage became extinct on his death.

Macaulay's nephew, Sir George Trevelyan, Bt, wrote the "Life and Letters" of his uncle. His great-nephew was the Cambridge historian G. M. Trevelyan.

Literary works

As a young man he composed the ballads Ivry and The Armada,[37] which he later included as part of Lays of Ancient Rome, a series of very popular poems about heroic episodes in Roman history which he began composing in India and continued in Rome, finally publishing in 1842.[38] The most famous of them, Horatius, concerns the heroism of Horatius Cocles. It contains the oft-quoted lines:[39]

His essays, originally published in the Edinburgh Review, were collected as Critical and Historical Essays in 1843.[40]

Historian

During the 1840s, Macaulay undertook his most famous work, The History of England from the Accession of James the Second, publishing the first two volumes in 1848. At first, he had planned to bring his history down to the reign of George III. After publication of his first two volumes, his hope was to complete his work with the death of Queen Anne in 1714.[41]

The third and fourth volumes, bringing the history to the Peace of Ryswick, were published in 1855. At his death in 1859 he was working on the fifth volume. This, bringing the History down to the death of William III, was prepared for publication by his sister, Lady Trevelyan, after his death.[42]

Political writing

Macaulay's political writings are famous for their ringing prose and for their confident, sometimes dogmatic, emphasis on a progressive model of British history, according to which the country threw off superstition, autocracy and confusion to create a balanced constitution and a forward-looking culture combined with freedom of belief and expression. This model of human progress has been called the Whig interpretation of history

This philosophy appears most clearly in the essays Macaulay wrote for the Edinburgh Review and other publications, which were collected in book form and a steady best-seller throughout the 19th century. But it is also reflected in History; the most stirring passages in the work are those that describe the "Glorious Revolution" of 1688.

Macaulay's approach has been criticised by later historians for its one-sidedness and its complacency. Karl Marx referred to him as a 'systematic falsifier of history'.[43] His tendency to see history as a drama led him to treat figures whose views he opposed as if they were villains, while characters he approved of were presented as heroes. Macaulay goes to considerable length, for example, to absolve his main hero William III of any responsibility for the Glencoe massacre. Winston Churchill devoted a four-volume biography of the Duke of Marlborough to rebutting Macaulay's slights on his ancestor, expressing hope "to fasten the label 'Liar' to his genteel coat-tails".[44]

Legacy as a historian

The Liberal historian Lord Acton read Macaulay's History of England four times and later described himself as "a raw English schoolboy, primed to the brim with Whig politics" but "not Whiggism only, but Macaulay in particular that I was so full of." However, after coming under German influence Acton would later find fault in Macaulay.[45] In 1880 Acton classed Macaulay (with Burke and Gladstone) as one "of the three greatest Liberals".[46] In 1883, he advised Mary Gladstone:

In 1885, Acton asserted that:

In 1888, Acton wrote that Macaulay "had done more than any writer in the literature of the world for the propagation of the Liberal faith, and he was not only the greatest, but the most representative, Englishman then living".[49]

W. S. Gilbert described Macaulay's wit, "who wrote of Queen Anne" as part of Colonel Calverley's Act I patter song in the libretto of the 1881 operetta Patience. (This line may well have been a joke about the Colonel's pseudo-intellectual bragging, as most educated Victorians knew that Macaulay did not write of Queen Anne; the History encompasses only as far as the death of William III in 1702, who was succeeded by Anne.)

Herbert Butterfield's The Whig Interpretation of History (1931) attacked Whig history. The Dutch historian Pieter Geyl, writing in 1955, considered Macaulay's Essays as "exclusively and intolerantly English".[50]

On 7 February 1954, Lord Moran, doctor to the Prime Minister, Sir Winston Churchill, recorded in his diary:

George Richard Potter, Professor and Head of the Department of History at the University of Sheffield from 1931 to 1965, claimed "In an age of long letters ... Macaulay's hold their own with the best".[52] However Potter also claimed:

With regards to Macaulay's determination to inspect physically the places mentioned in his History, Potter said:

Potter noted that Macaulay has had many critics, some of whom put forward some salient points about the deficiency of Macaulay's History but added: "The severity and the minuteness of the criticism to which the History of England has been subjected is a measure of its permanent value. It is worth every ounce of powder and shot that is fired against it." Potter concluded that "in the long roll of English historical writing from Clarendon to Trevelyan only Gibbon has surpassed him in security of reputation and certainty of immortality".[55]

Piers Brendon wrote that Macaulay is "the only British rival to Gibbon."[56] In 1972, J. R. Western wrote that: "Despite its age and blemishes, Macaulay's History of England has still to be superseded by a full-scale modern history of the period."[57] In 1974 J. P. Kenyon stated that: "As is often the case, Macaulay had it exactly right."[58]

W. A. Speck wrote in 1980, that a reason Macaulay's History of England "still commands respect is that it was based upon a prodigious amount of research".[59] Speck claimed:

According to Speck:

[Macaulay too often] denies the past has its own validity, treating it as being merely a prelude to his own age. This is especially noticeable in the third chapter of his History of England, when again and again he contrasts the backwardness of 1685 with the advances achieved by 1848. Not only does this misuse the past, it also leads him to exaggerate the differences.[60]

On the other hand, Speck also wrote that Macaulay "took pains to present the virtues even of a rogue, and he painted the virtuous warts and all",[61] and that "he was never guilty of suppressing or distorting evidence to make it support a proposition which he knew to be untrue".[62] Speck concluded:

In 1981, J. W. Burrow argued that Macaulay's History of England:

In 1982, Gertrude Himmelfarb wrote:

Himmelfarb also laments that "the history of the History is a sad testimonial to the cultural regression of our times".[65]

In the novel Marathon Man and its film adaptation, the protagonist was named 'Thomas Babington' after Macaulay.[66]

In 2008, Walter Olson argued for the pre-eminence of Macaulay as a British classical liberal.[67]

Works

• Works by Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay at Project Gutenberg

• Lays of Ancient Rome originally published in the year 1842.

• The History of England from the Accession of James II . Philadelphia: Porter & Coates. 1848 – via Wikisource.

• 5 vols (1848): Vol 1, Vol 2, Vol 3, Vol 4, Vol 5 at Internet Archive

• 5 vols (1848): Vol. 1, Vol. 2, Vol. 3, Vol. 4, Vol. 5 at Project Gutenberg

• volumes 1–3 at LibriVox.org

• Critical and Historical Essays(1843), 2 vols, edited by Alexander James Grieve. Vol. 1, Vol. 2

• "Social and Industrial Capacities of the Negroes". Critical Historical and Miscellaneous Essays with a Memoir and Index. Vol. V. and VI. Mason, Baker & Pratt. 1873.

• Lays of Ancient Rome: With Ivry, and The Armada. Longmans, Green, and Company. 1881.

• William Pitt, Earl of Chatham: Second Essay (Maynard, Merrill, & Company, 1892, 110 pages)

• The Miscellaneous Writings and Speeches of Lord Macaulay(1860), 4 vols Vol. 1, Vol. 2, Vol. 3, Vol. 4

• Machiavelli on Niccolò Machiavelli (1850).

• The Letters of Thomas Babington Macaulay(1881), 6 vols, edited by Thomas Pinney.

• The Journals of Thomas Babington Macaulay, 5 vols, edited by William Thomas.

• Macaulay index entry at Poets' Corner

• Lays of Ancient Rome (Complete) at Poets' Corner with an introduction by Bob Blair

• Works by Thomas Babington Macaulay at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

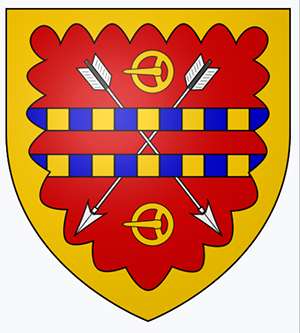

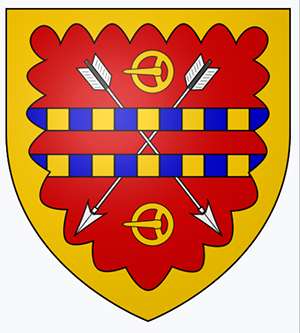

Arms

Coat of arms of Thomas Babington Macaulay

Notes

The arms, crest and motto allude to the heraldry of the MacAulays of Ardincaple; however Thomas Babington Macaulay was not related to this clan at all. He was, instead, descended from the unrelated Macaulays of Lewis. Such adoptions were not uncommon at the time according to the Scottish heraldic historian Peter Drummond-Murray but usually made from ignorance rather than deceit.

Crest

Upon a rock a boot proper thereon a spur Or.[68]

Escutcheon

Gules two arrows in saltire points downward argent surmounted by as many barrulets compony Or and azure between two buckles in pale of the third a bordure engrailed also of the third.[68]

Supporters

Two herons proper.[68]

Motto

Dulce periculum[68] (translation from Latin: "danger is sweet").

See also

• Philosophic Whigs

• Whig history further explains the interpretation of history that Macaulay espoused.

• Samuel Rogers#Middle life and friendships

Portals:

• Biography

• Poetry

• United Kingdom

Citations

1. MacKenzie, John (January 2013), "A family empire", BBC History Magazine

2. Biographical index of former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. 2006. ISBN 090219884X.

3. "Thomas Babbington Macaulay". Josephsmithacademy. Archived from the original on 12 May 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

4. Symonds, P. A. "Babington, Thomas (1758–1837), of Rothley Temple, nr. Leicester". History of Parliament on-line. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

5. Kuper 2009, p. 146.

6. Knight 1867, p. 8.

7. Sullivan 2010, p. 21.

8. "Macaulay, Thomas Babington (FML817TB)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

9. Thomas, William. "Macaulay, Thomas Babington, Baron Macaulay (1800–1859), historian, essayist, and poet". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/17349. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

10. Galton 1869, p. 23.

11. Sullivan 2010, p. 9.

12. Pattison 1911, p. 193.

13. Rupprecht, Anita (September 2012). "'When he gets among his countrymen, they tell him that he is free': Slave Trade Abolition, Indentured Africans and a Royal Commission". Slavery & Abolition. 33 (3): 435–455. doi:10.1080/0144039X.2012.668300. S2CID 144301729.

14. Thomas Babington Macaulay, Social and Industrial Capacities of the Negroes (Edinburgh Review, March 1827), collected in Critical, Historical and Miscellaneous Essays, Volume 6 (1860), pp. 361–404.

15. Taylor, Michael (2020). The Interest: How the British Establishment Resisted The Abolition of Slavery. Penguin Random House (Paperback). pp. 107–116.

16. Cropper 1864: see entry for 22 November 1831

17. Sullivan 2010, p. 466.

18. Evans 2002, p. 260.

19. Spear 1938, pp. 78–101.

20. ""Government of India" - A Speech Delivered in the House of Commons on the 10th of July 1833". http://www.columbia.edu. Columbia university and Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

21. "377: The British colonial law that left an anti-LGBTQ legacy in Asia". http://www.bbc.co.uk. BBC News. 28 June 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

22. Think it Over: Macaulay and India's rootless generations[permanent dead link]

23. Watt & Mann 2011, p. 23.

24. Losurdo 2014, p. 250.

25. Losurdo 2014, pp. 250–251.

26. "No. 19774". The London Gazette. 1 October 1839. p. 1841.

27. "Macaulay's speeches on copyright law". Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

28. "Lord Macaulay". Bartleby. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

29. "The Rector". Glasgow university. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

30. "Biography of Lord Macaulay". Sacklunch. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

31. "Lord Macaulay". The Sydney Morning Herald. 15 March 1860. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

32. "No. 22039". The London Gazette. 11 September 1857. p. 3075.

33. "Thomas Babington Macaulay". Clanmacfarlanegenealogy. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

34. "From the Director" (PDF). Face to Face (16). National Portrait Gallery. Spring 2006. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

35. "Death of Lord Macaulay". The New York Times. 17 January 1960. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

36. Stanley, A. P., Historical Memorials of Westminster Abbey (London; John Murray; 1882), p. 222.

37. Macaulay 1881.

38. Sullivan, Robert E (2009). Macaulay. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 251. ISBN 978-0674054691. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

39. "Thomas Babington Macaulay, Lord Macaulay Horatius". English verse. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

40. Macaulay 1941, p. x.

41. Macaulay 1848, Vol. V, title page and prefatory "Memoir of Lord Macaulay".

42. Macaulay 1848.

43. Marx 1906, p. 788, Ch. XXVII: "I quote Macaulay, because as a systematic falsifier of history he minimizes facts of this kind as much as possible."

44. Churchill 1947, p. 132: "It is beyond our hopes to overtake Lord Macaulay. The grandeur and sweep of his story-telling carries him swiftly along, and with every generation he enters new fields. We can only hope that Truth will follow swiftly enough to fasten the label 'Liar' to his genteel coat-tails."

45. Hill 2011, p. 25.

46. Paul 1904, p. 57.

47. Paul 1904, p. 173.

48. Paul 1904, p. 210.

49. Lord Acton 1919, p. 482.

50. Geyl 1958, p. 30.

51. Lord Moran 1968, pp. 553–554.

52. Potter 1959, p. 10.

53. Potter 1959, p. 25.

54. Potter 1959, p. 29.

55. Potter 1959, p. 35.

56. Brendon 2010, p. 126.

57. Western 1972, p. 403.

58. Kenyon 1974, p. 47, n. 14.

59. Speck 1980, p. 57.

60. Speck 1980, p. 64.

61. Speck 1980, p. 65.

62. Speck 1980, p. 67.

63. Burrow 1983.

64. Himmelfarb 1986, p. 163.

65. Himmelfarb 1986, p. 165.

66. Goldman 1974, p. 20.

67. Olson 2008, pp. 309–310.

68. Burke 1864, p. 635.

[See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Babington_Macaulay for "General and cited sources," "Further reading," and "External links"]

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/25/24

The Right Honourable

The Lord Macaulay

PC FRS FRSE

Photogravure of Macaulay by Antoine Claudet

Secretary at War

In office: 27 September 1839 – 30 August 1841

Monarch: Victoria

Prime Minister: The Viscount Melbourne

Preceded by: Viscount Howick

Succeeded by: Sir Henry Hardinge

Paymaster General

In office: 7 July 1846 – 8 May 1848

Monarch: Victoria

Prime Minister: Lord John Russell

Preceded by: Hon. Bingham Baring

Succeeded by: The Earl Granville

Personal details

Born: 25 October 1800, Leicestershire, England

Died: 28 December 1859 (aged 59), London, England

Political party: Whig

Parent(s): Zachary Macaulay; Selina Mills

Alma mater: Trinity College, Cambridge

Occupation: Politician

Profession: Historian, poet

In literary criticism, purple prose is overly ornate prose text that may disrupt a narrative flow by drawing undesirable attention to its own extravagant style of writing, thereby diminishing the appreciation of the prose overall. Purple prose is characterized by the excessive use of adjectives, adverbs, and metaphors. When it is limited to certain passages, they may be termed purple patches or purple passages, standing out from the rest of the work.

Purple prose is criticized for desaturating the meaning in an author's text by overusing melodramatic and fanciful descriptions. As there is no precise rule or absolute definition of what constitutes purple prose, deciding if a text, passage, or complete work has fallen victim is subjective. According to Paul West, "It takes a certain amount of sass to speak up for prose that's rich, succulent and full of novelty. Purple is immoral, undemocratic and insincere; at best artsy, at worst the exterminating angel of depravity."

-- Purple prose, by Wikipedia

From a child Surajah Dowlah had hated the English. It was his whim to do so; and his whims were never opposed. He had also formed a very exaggerated notion of the wealth which might be obtained by plundering them; and his feeble and uncultivated mind was incapable of perceiving that the riches of Calcutta, had they been even greater than he imagined, would not compensate him for what he must lose, if the European trade, of which Bengal was a chief seat, should be driven by his violence to some other quarter. Pretexts for a quarrel were readily found. The English, in expectation of a war with France, had begun to fortify their settlement without special permission from the Nabob. A rich native, whom he longed to plunder, had taken refuge at Calcutta, and had not been delivered up. On such grounds as these Surajah Dowlali marched with a great army against Fort William.

The servants of the Company at Madras had been forced by Dupleix to become statesmen and soldiers. Those in Bengal were still mere traders, and were terrified and bewildered by the approaching danger. The governor, who had heard much of Surajah Dowlah’s cruelty, was frightened out of his wits, jumped into a boat, and took refuge in the nearest ship. The military commandant thought that he could not do better than follow so good an example. The fort was taken after a feeble resistance; and great numbers of the English fell into the hands of the conquerors. The Nabob seated himself with regal pomp in the principal hall of the factory, and ordered Mr. Holwell, the first in rank among the prisoners, to be brought before him. His Highness talked about the insolence of the English, and grumbled at the smallness of the treasure which he had found; but promised to spare their lives, and retired to rest.

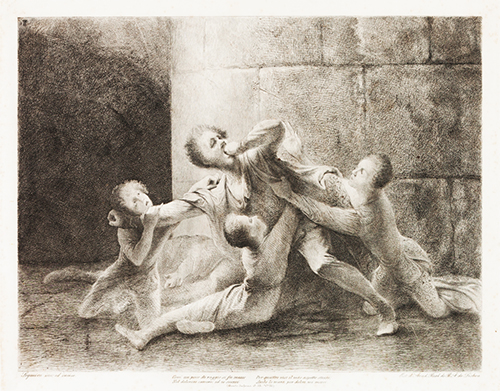

Then was committed that great crime, memorable for its singular atrocity, memorable for the tremendous retribution by which it was followed. The English captives were left at the mercy of the guards, and the guards determined to secure them for the night in the prison of the garrison, a chamber known by the fearful name of the Black Hole. Even for a single European malefactor, that dungeon would, in such a climate, have been too close and narrow. The space was only twenty feet square. The air-holes were small and obstructed. It was the summer solstice, the season when the fierce heat of Bengal can scarcely be rendered tolerable to natives of England by lofty halls and by the constant waving of fans. The number of the prisoners was one hundred and forty-six. When they were ordered to enter the cell, they imagined that the soldiers were joking; and, being in high spirits on account of the promise of the Nabob to spare their lives, they laughed and jested at the absurdity of the notion. They soon discovered their mistake. They expostulated; they entreated; but in vain. The guards threatened to cut down all who hesitated. The captives were driven into the cell at the point of the sword, and the door was instantly shut and locked upon them.

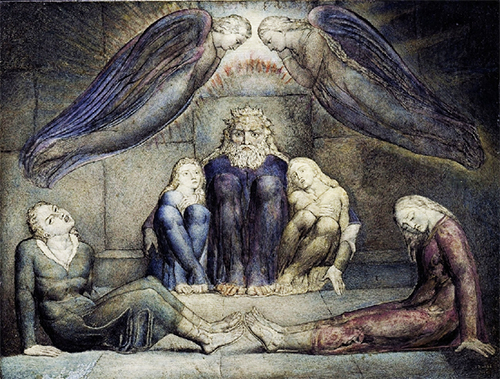

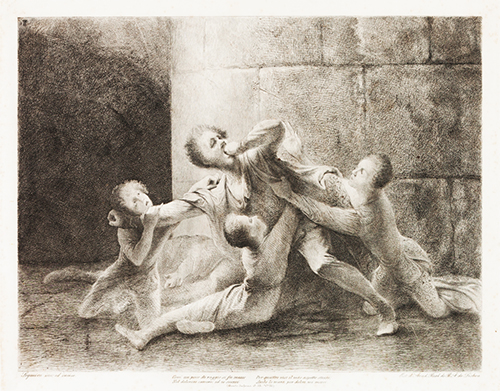

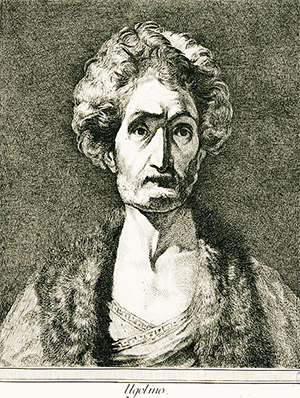

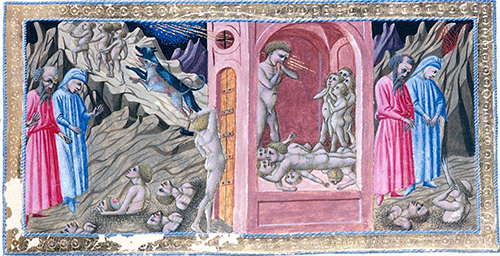

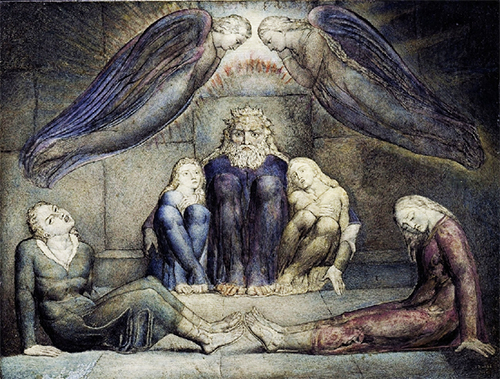

Nothing in history or fiction, not even the story which Ugolino told in the sea of everlasting ice, after he had wiped his bloody lips on the scalp of his murderer, approaches the horrors which were recounted by the few survivors of that night. They cried for mercy. They strove to burst the door. Holwell who, even in that extremity, retained some presence of mind, offered large bribes to the gaolers. But the answer was that nothing could be done without the Nabob’s orders, that the Nabob was asleep, and that he would be angry if anybody woke him. Then the prisoners went mad with despair. They trampled each other down, fought for the places at the windows, fought for the pittance of water with which the cruel mercy of the murderers mocked their agonies, raved, prayed, blasphemed, implored the guards to fire among them. The gaolers in the mean time held lights to the bars, and shouted with laughter at the frantic struggles of their victims. At length the tumult died away in low gaspings and moanings.

The day broke. The Nabob had slept off his debauch, and permitted the door to be opened. But it was some time before the soldiers could make a lane for the survivors, by piling up on each side the heaps of corpses on which the burning climate had already begun to do its loathsome work. When at length a passage was made, twenty-three ghastly figures, such as their own mothers would not have known, staggered one by one out of the charnel-house. A pit was instantly dug. The dead bodies, a hundred and twenty-three in number, were flung into it promiscuously and covered up.

But these things which, after the lapse of more than eighty years, cannot be told or read without horror, awakened neither remorse nor pity in the bosom of the savage Nabob. He inflicted no punishment on the murderers. He showed no tenderness to the survivors. Some of them, indeed, from whom nothing was to be got, were suffered to depart; but those from whom it was thought that any thing could be extorted were treated with execrable cruelty. Holwell, unable to walk, was carried before the tyrant, who reproached him, threatened him, and sent him up the country in irons, together with some other gentlemen who were suspected of knowing more than they chose to tell about the treasures of the Company. These persons, still bowed down by the sufferings of that great agony, were lodged in miserable sheds, and fed only with grain and water, till at length the intercessions of the female relations of the Nabob procured their release. One Englishwoman had survived that night. She was placed in the harem of the Prince at Moorshedabad. Surajah Dowlah, in the mean time, sent letters to his nominal sovereign at Delhi, describing the late conquest in the most pompous language. He placed a garrison in Fort William, forbade Englishmen to dwell in the neighbourhood, and directed that, in memory of his great actions, Calcutta should thenceforward be called Alinagore, that is to say, the Port of God.

-- Lord Clive, by Thomas Babington Macaulay

... The fifth point, if the reasoning is sound, and the reader will judge of this, immediately characterises the whole narrative as a daring piece of unblushing impudence.

-- The Black Hole -- The Question of Holwell's Veracity, by J. H. Little, Bengal, Past & Present, Journal of the Calcutta Historical Society, Vol. XI, Part 1, July-Sept., 1915

-- Minute on Education, by the Hon'ble T. B. Macaulay, by Thomas Babington Macaulay,February 2, 1835

-- Full Proceedings of the Black Hole Debate, Bengal, Past & Present, Journal of the Calcutta Historical Society, Vol. XII. Jan – June, 1916

-- A Genuine Narrative of the deplorable Deaths of the English Gentlemen, and Others, who were suffocated in the Black Hole in Fort-William, at Calcutta, in the Kingdom of Bengal; in the Night succeeding the 20th Day of June 1756., In a Letter to a Friend, from India Tracts, by Mr. J.Z. Holwell, and Friends.

-- Interesting Historical Events, Relative to the Provinces of Bengal, and the Empire of Indostan. With a Seasonable Hint and Persuasive to the Honourable The Court of Directors of the East India Company. As Also The Mythology and Cosmogony, Facts and Festivals of the Gentoo's, followers of the Shastah. And a Dissertation on the Metempsychosis, commonly, though erroneously, called the Pythagorean Doctrine. Part II. By J.Z. Holwell, Esq.

-- Forging Indian Religion: East India Company Servants and the Construction of ‘Gentoo’/‘Hindoo’ Scripture in the 1760s, by Jessica Patterson

-- Holwell's Religion of Paradise, Excerpt from The Birth of Orientalism, by Urs App

-- The Whig Interpretation of History, by Herbert Butterfield, M.A., 1965

Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay, PC, FRS, FRSE (/ˈbæbɪŋtən məˈkɔːli/; 25 October 1800 – 28 December 1859) was a British historian, poet, and Whig politician, who served as the Secretary at War between 1839 and 1841, and as the Paymaster General between 1846 and 1848.

Macaulay's The History of England, which expressed his contention of the superiority of the Western European culture and of the inevitability of its sociopolitical progress, is a seminal example of Whig history that remains commended for its prose style.[1]

Early life

Macaulay was born at Rothley Temple[2] in Leicestershire on 25 October 1800, the son of Zachary Macaulay, a Scottish Highlander, who became a colonial governor and abolitionist, and Selina Mills of Bristol, a former pupil of Hannah More.[3] They named their first child after his uncle Thomas Babington, a Leicestershire landowner and politician,[4][5] who had married Zachary's sister Jean [Aunt Jean is married to Uncle Babington].[6] The young Macaulay was noted as a child prodigy; as a toddler, gazing out of the window from his cot at the chimneys of a local factory, he is reputed to have asked his father whether the smoke came from the fires of hell.[7]

He was educated at a private school in Hertfordshire, and, subsequently, at Trinity College, Cambridge,[8] where he won several prizes,[/u][/b] including the Chancellor's Gold Medal in June 1821,[9] and where he in 1825 published a prominent essay on Milton in the Edinburgh Review. Macaulay did not while at Cambridge study classical literature, which he subsequently read in India. He in his letters describes his reading of the Aeneid whilst he was in Malvern in 1851, when he says he was moved to tears by Virgil's poetry.[10] He taught himself German, Dutch and Spanish, and was fluent in French.[11] He studied law and he was in 1826 called to the bar, before he took more interest in a political career.[12] Macaulay in the Edinburgh Review in 1827, and in a series of anonymous letters to The Morning Chronicle,[13] censured the analysis of indentured labour by the British Colonial Office expert Colonel Thomas Moody, Kt.[13][14] Macaulay's evangelical Whig father Zachary Macaulay, who desired a 'free black peasantry' rather than equality for Africans,[15] also censured, in the Anti-Slavery Reporter, Moody's contentions.[13]

Zachary Macaulay

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/30/24

Zachary Macaulay

Zachary Macaulay (Scottish Gaelic: Sgàire MacAmhlaoibh; 2 May 1768 – 13 May 1838) was a Scottish statistician and abolitionist who was a founder of London University and of the Society for the Suppression of Vice, and a Governor of British Sierra Leone.

Early life

Macaulay was born in Inveraray, Scotland, to Margaret Campbell and John Macaulay (1720 – 1789), who was a minister of the Church of Scotland and a grandson of Dòmhnall Cam. He had two brothers: Aulay Macaulay, who was an antiquary, and Colin Macaulay, who was a general and an abolitionist. Zachary Macaulay was not educated in, but taught himself, Greek and Latin and English literature.

Career

Macaulay worked in a merchant's office in Glasgow, where he fell into bad company and began to indulge in excessive drinking. In late 1784, when aged 16 years, he emigrated to Jamaica, where he worked as an assistant manager at a sugar plantation, at which he objected to slavery as a consequence of which he, contrary to the preference of his father, renounced his job and returned in 1789 to London, where he reduced his alcoholism and became a bookkeeper. He was influenced by Thomas Babington of Rothley Temple, Leicestershire, an evangelical Whig abolitionist whom his sister Jean had married, and by whom he was influenced and introduced to William Wilberforce and Henry Thornton.Thomas Babington

by Wikipedia

Accessed: August 30, 2024

Thomas Babington of Rothley Temple (1758–1837), by Sir Thomas Lawrence

Thomas Babington of Rothley Temple (/ˈbæbɪŋtən/; 18 December 1758 – 21 November 1837) was an English philanthropist and politician. He was a member of the Clapham Sect, alongside more famous abolitionists such as William Wilberforce and Hannah More. An active anti-slavery campaigner, he had reservations about the participation of women associations in the movement.[1]

Early life and education

He was the eldest son of Thomas Babington of Rothley Temple, Leicestershire, from whom he inherited Rothley and other land in Leicestershire in 1776. A member of the Babington family, he was educated at Rugby School and St John's College, Cambridge[2] where he met William Wilberforce and other prominent anti-slavery agitators.

Anti-slavery and philanthropy

Babington was an evangelical Christian of independent means who devoted himself to a number of good causes. His home at Rothley Temple was regularly used by Wilberforce and associates for abolitionist meetings, and it was where the bill to abolish slavery was drafted. There is a stone memorial to commemorate to this on the front lawn of Rothley which still stands today.

Babington's base in London was 17 Downing Street. He shared use of this residence with his brother-in-law, General Colin Macaulay who was similarly active in the abolitionist cause.[3]

In addition to his anti-slavery work, he also offered to pay half the cost of smallpox inoculation for people in Rothley in 1784–5. He set up a local Friendly Society to purchase corn for sale to the poor at a lower price to improve the lives and diet of his estate workers. Trusts he set up to provide housing in local villages still exist today.

Babington was active politically, and supported moves to extend voting rights to more people. He was High Sheriff of Leicestershire in 1780 and MP for Leicester from 1800 to 1818.

Family

Jean Babington (Macaulay), by Sir Thomas Lawrence

On 8 October 1787 Babington married Jean Macaulay, daughter of the Rev. John Macaulay (1720-1789) of Cardross, Dumbartonshire. Jean came from a family who like Babington, were prominently involved in the anti-slavery movement. This included two brothers Zachary Macaulay, and General Colin Macaulay: Thomas Babington Macaulay was Jean's nephew. Thomas and Jean had six sons and four daughters [=10 children]

• Thomas Gisborne Babington (1788–1871)

• Rev. John Babington (1791–?)

• Matthew Babington, JP (1792–?)

• George Gisborne Babington, FRCS (1794–1856)

• William Henry Babington, E.I.C.C.S (1803–1867)

• Lieutenant Charles Roos Babington (1806–1826)

• Lydia Rose Babington

• Jean Babington (–1839)

• Mary Babington (1799–1858), wife of Sir James Parker, Vice-Chancellor

• Margaret Anne Babington (–1819)

Babington died at Rothley Temple in 1837 at the age of 78, and is buried in the chapel there. His wife Jean died on 21 September 1845.

References

• United Kingdom portal

• Biography portal

1. Clare Midgley, Women against slavery (Routledge, 1992, p. 56)

2. "Babington, Thomas (BBNN775T)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

3. Colin Ferguson Smith, "A Life of General Colin Macaulay" (Privately Published 2019 - ISBN 978-1-78972-649-7), p 44.

Macaulay in 1790 visited Sierra Leone, the West African colony that was founded by the Sierra Leone Company for emancipated slaves. He returned in 1792 to serve on its Council, by which he was invested as Governor in 1794, as which he remained until 1799.

Macaulay became a member of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, with William Wilberforce, to campaign for the abolition of slavery in the British Empire. He later became the secretary of the African Institution. He and Wilberforce also became members of the Clapham Sect of evangelical Whigs, that included Henry Thornton and Edward Eliot, for whom he edited the magazine, the Christian Observer, from 1802 to 1816. Macaulay served on committees that established London University, and that established the Society for the Suppression of Vice. He was also a fellow of the Royal Society, and an active supporter of the British and Foreign Bible Society, and of the Cheap Repository Tracts, and of the Church Missionary Society. Macaulay contributed to the 1823 foundation of the Society for the Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery, and he was editor of its publication, the Anti-Slavery Reporter, in which he censured the analysis of indentured labour by the British Colonial Office expert Thomas Moody[1] However, Zachary Macaulay desired a 'free black peasantry' rather than equality for Africans.[2]

Stone plaque erected in 1930 by London County Council at 5 The Pavement, Clapham

Macaulay died on 13 May 1838 in London, where he was buried in St George's Gardens, Bloomsbury, and where a memorial to him was erected in Westminster Abbey.[3]

Personal life

Macaulay married Selina Mills, who was the daughter of the Quaker printer Thomas Mills. They were introduced by Hannah More on 26 August 1799.[4] They settled in Clapham, Surrey, and had several children including Thomas Babington Macaulay, who was a Whig historian and politician, and Hannah More Macaulay (1810 – 1873), who married Sir Charles Trevelyan, 1st Baronet and was the mother of Sir George Trevelyan, 2nd Baronet.

Further reading

• Carey, Brycchan. British Abolitionism and the Rhetoric of Sensibility: Writing, Sentiment, and Slavery, 1760–1807 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005)

• Hall, Catherine. Macaulay and Son: Architects of Imperial Britain (Yale UP, 2013)

• Hochschild, Adam. Bury the Chains, The British Struggle to Abolish Slavery (Basingstoke: Pan Macmillan, 2005)

• Macaulay, Zachary (1900). Knutsford, Margaret Jean Trevelyan (ed.). Life and Letters of Zachary Macaulay. Edward Arnold.

• Oldfield, J.R. Thomas Macaulay in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: University Press, 2006)

• Stephen, Leslie (1893). "Macaulay, Zachary" . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 34. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

• Stott, Anne. Hannah More – The First Victorian (Oxford: University Press, 2003)

• Whyte, I. Zachary Macaulay 1768–1838: The Steadfast Scot in the British Anti-Slavery Movement. (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2011). ISBN 978-1781388471.

References

1. Rupprecht, Anita (September 2012). "'When he gets among his countrymen, they tell him that he is free': Slave Trade Abolition, Indentured Africans and a Royal Commission". Slavery & Abolition. 33 (3): 435–455. doi:10.1080/0144039X.2012.668300. S2CID 144301729.

2. Taylor, Michael (2020). The Interest: How the British Establishment Resisted The Abolition of Slavery. Penguin Random House (Paperback). pp. 107–116.

3. Stanley, A.P., Historical Memorials of Westminster Abbey (London; John Murray; 1882), p. 248.

4. Stott, Anne (1 March 2012). "'Jacob and Rachel': Zachary Macaulay and Selina Mills". Oxford Scholarship. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199699391.001.0001. ISBN 9780199699391. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

External links

• Article Macaulay, Zachary (and Macaulay, Aulay) in the Dictionary of Scottish Church History and Theology (Edinburgh, 1993) ISBN 0-567-09650-5

• Negro slavery By Zachary Macaulay. Published in 1824. Cornell University Library Samuel J. May Anti-Slavery Collection. {Reprinted by} Cornell University Library Digital Collections

Macaulay, who did not marry nor have children, was rumoured to have fallen in love with Maria Kinnaird, who was the wealthy ward of Richard 'Conversation' Sharp.[16] Macaulay's strongest emotional relationships were with his youngest sisters: Margaret, who died while he was in India, and Hannah, to whose daughter Margaret, whom he called 'Baba', he was also attached.[17]

India (1834–1838)

Macaulay by John Partridge

Macaulay in 1830 accepted the invitation of the Marquess of Lansdowne that he become Member of Parliament for the pocket borough of Calne. Macaulay's maiden speech in Parliament advocated abolition of the civil disabilities of the Jews in the UK. He extensively wrote that Islam and Hinduism had little to offer to the world, and that Arabic, Persian and Sanskrit literature had little contribution to humanity.[9] Macaulay's subsequent speeches in favour of parliamentary reform were commended.[9] He became MP for Leeds[9] subsequent to the 1833 enactment of the Reform Act 1832, by which Calne's representation was reduced from two MPs to one, and by which Leeds, which had not been represented before, had two MPs. Macaulay remained grateful to his former patron, Lansdowne, who remained his friend.

Macaulay was Secretary to the Board of Control under Lord Grey from 1832 until he in 1833 required, as a consequence of the penury of his father, a more remunerative office, than that of the unremunerated office of an MP, from which he resigned after the passing of the Government of India Act 1833 to accept an appointment as first Law Member of the Governor-General's Council. Macaulay in 1834 went to India, where he served on the Supreme Council between 1834 and 1838.[18] His Minute on Indian Education of February 1835 was primarily responsible for the introduction of Western institutional education to India.

Macaulay recommended the introduction of the English language as the official language of secondary education instruction in all schools where there had been none before, and the training of English-speaking Indians as teachers.[1] In his minute, he urged Lord William Bentinck, the then-Governor-General to reform secondary education on utilitarian lines to deliver "useful learning", a phrase that to him was synonymous with Western culture. There was no tradition of secondary education in vernacular languages; the institutions supported by the East India Company taught either in Sanskrit or Persian[citation needed]. Hence, he argued, "We have to educate a people who cannot at present be educated by means of their mother-tongue. We must teach them some foreign language." Macaulay argued that Sanskrit and Persian were no more accessible than English to the speakers of the Indian vernacular languages and existing Sanskrit and Persian texts were of little use for 'useful learning'. In one of the less scathing passages of the Minute he wrote:

I have no knowledge of either Sanskrit or Arabic. But I have done what I could to form a correct estimate of their value. I have read translations of the most celebrated Arabic and Sanskrit works. I have conversed both here and at home with men distinguished by their proficiency in the Eastern tongues. I am quite ready to take the Oriental learning at the valuation of the Orientalists themselves. I have never found one among them who could deny that a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia.

He further argued:

It will hardly be disputed, I suppose, that the department of literature in which the Eastern writers stand highest is poetry. And I certainly never met with any orientalist who ventured to maintain that the Arabic and Sanskrit poetry could be compared to that of the great European nations. But when we pass from works of imagination to works in which facts are recorded and general principles investigated, the superiority of the Europeans becomes absolutely immeasurable. It is, I believe, no exaggeration to say that all the historical information which has been collected from all the books written in the Sanskrit language is less valuable than what may be found in the most paltry abridgments used at preparatory schools in England. In every branch of physical or moral philosophy, the relative position of the two nations is nearly the same.

Hence, from the sixth year of schooling onwards, instruction should be in European learning, with English as the medium of instruction. This would create a class of anglicised Indians who would serve as cultural intermediaries between the British and the Indians; the creation of such a class was necessary before any reform of vernacular education. He stated:

I feel with them that it is impossible for us, with our limited means, to attempt to educate the body of the people. We must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern; a class of persons Indian in blood and colour, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect. To that class we may leave it to refine the vernacular dialects of the country, to enrich those dialects with terms of science borrowed from the Western nomenclature, and to render them by degrees fit vehicles for conveying knowledge to the great mass of the population.

Macaulay's minute largely coincided with Bentinck's views[19] and Bentinck's English Education Act 1835 closely matched Macaulay's recommendations (in 1836, a school named La Martinière, founded by Major General Claude Martin, had one of its houses named after him), but subsequent Governors-General took a more conciliatory approach to existing Indian education.

His final years in India were devoted to the creation of a Penal Code, as the leading member of the Law Commission. In the aftermath of the Indian Mutiny of 1857, Macaulay's criminal law proposal was enacted.[citation needed] The Indian Penal Code in 1860 was followed by the Criminal Procedure Code in 1872 and the Civil Procedure Code in 1908. The Indian Penal Code inspired counterparts in most other British colonies, and to date many of these laws are still in effect in places as far apart as Pakistan, Malaysia, Myanmar, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nigeria and Zimbabwe, as well as in India itself.[20] This includes Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which remains the basis for laws which criminalize homosexuality in several Commonwealth nations.[21]

In Indian culture, the term "Macaulay's Children" is sometimes used to refer to people born of Indian ancestry who adopt Western culture as a lifestyle, or display attitudes influenced by colonialism ("Macaulayism")[22] – expressions used disparagingly, and with the implication of disloyalty to one's country and one's heritage. In independent India, Macaulay's idea of the civilising mission has been used by Dalitists, in particular by neo-liberalist Chandra Bhan Prasad, as a "creative appropriation for self-empowerment", based on the view that the Dalit community was empowered by Macaulay's deprecation of Hindu culture and support for Western-style education in India.[23]

Domenico Losurdo states that "Macaulay acknowledged that the English colonists in India behaved like Spartans confronting helots: we are dealing with 'a race of sovereign' or a 'sovereign caste', wielding absolute power over its 'serfs'."[24] Losurdo noted that this did not prompt any doubts from Macaulay over the right of Britain to administer its colonies in an autocratic fashion; for example, while Macaulay described the administration of governor-general of India Warren Hastings as being so despotic that "all the injustice of former oppressors, Asiatic and European, appeared as a blessing", he (Hastings) deserved "high admiration" and a rank among "the most remarkable men in our history" for "having saved England and civilisation".[25]

Return to British public life (1838–1857)

Macaulay by Sir Francis Grant

Returning to Britain in 1838, he became MP for Edinburgh in the following year. He was made Secretary at War in 1839 by Lord Melbourne and was sworn of the Privy Council the same year.[26] In 1841 Macaulay addressed the issue of copyright law. Macaulay's position, slightly modified, became the basis of copyright law in the English-speaking world for many decades.[27] Macaulay argued that copyright is a monopoly and as such has generally negative effects on society.[27] After the fall of Melbourne's government in 1841 Macaulay devoted more time to literary work, and returned to office as Paymaster General in 1846 in Lord John Russell's administration.

In the election of 1847 he lost his seat in Edinburgh.[28] He attributed the loss to the anger of religious zealots over his speech in favour of expanding the annual government grant to Maynooth College in Ireland, which trained young men for the Catholic priesthood; some observers also attributed his loss to his neglect of local issues. In 1849 he was elected Rector of the University of Glasgow, a position with no administrative duties, often awarded by the students to men of political or literary fame.[29] He also received the freedom of the city.[30]

In 1852, the voters of Edinburgh offered to re-elect him to Parliament. He accepted on the express condition that he need not campaign and would not pledge himself to a position on any political issue. Remarkably, he was elected on those terms.[citation needed] He seldom attended the House due to ill health. His weakness after suffering a heart attack caused him to postpone for several months making his speech of thanks to the Edinburgh voters. He resigned his seat in January 1856.[31] In 1857 he was raised to the peerage as Baron Macaulay, of Rothley in the County of Leicester,[32] but seldom attended the House of Lords.[31]

Later life (1857–1859)

The Funeral of Thomas Babington Macaulay, Baron Macaulay, by Sir George Scharf

Macaulay sat on the committee to decide on the historical subjects to be painted in the new Palace of Westminster.[33] The need to collect reliable portraits of notable figures from history for this project led to the foundation of the National Portrait Gallery, which was formally established on 2 December 1856.[34] Macaulay was amongst its founding trustees and is honoured with one of only three busts above the main entrance.

During his later years his health made work increasingly difficult for him. He died of a heart attack on 28 December 1859, aged 59, leaving his major work, The History of England from the Accession of James the Second incomplete.[35] On 9 January 1860 he was buried in Westminster Abbey, in Poets' Corner,[36] near a statue of Addison.[9] As he had no children, his peerage became extinct on his death.

Macaulay's nephew, Sir George Trevelyan, Bt, wrote the "Life and Letters" of his uncle. His great-nephew was the Cambridge historian G. M. Trevelyan.

Literary works

As a young man he composed the ballads Ivry and The Armada,[37] which he later included as part of Lays of Ancient Rome, a series of very popular poems about heroic episodes in Roman history which he began composing in India and continued in Rome, finally publishing in 1842.[38] The most famous of them, Horatius, concerns the heroism of Horatius Cocles. It contains the oft-quoted lines:[39]

Then out spake brave Horatius,

The Captain of the Gate:

"To every man upon this earth

Death cometh soon or late.

And how can man die better

Than facing fearful odds,

For the ashes of his fathers,

And the temples of his gods?"

His essays, originally published in the Edinburgh Review, were collected as Critical and Historical Essays in 1843.[40]

Historian

During the 1840s, Macaulay undertook his most famous work, The History of England from the Accession of James the Second, publishing the first two volumes in 1848. At first, he had planned to bring his history down to the reign of George III. After publication of his first two volumes, his hope was to complete his work with the death of Queen Anne in 1714.[41]

The third and fourth volumes, bringing the history to the Peace of Ryswick, were published in 1855. At his death in 1859 he was working on the fifth volume. This, bringing the History down to the death of William III, was prepared for publication by his sister, Lady Trevelyan, after his death.[42]

Political writing

Macaulay's political writings are famous for their ringing prose and for their confident, sometimes dogmatic, emphasis on a progressive model of British history, according to which the country threw off superstition, autocracy and confusion to create a balanced constitution and a forward-looking culture combined with freedom of belief and expression. This model of human progress has been called the Whig interpretation of history

Herbert butterfield's devastating attack on the whig interpretation of history

by Google AI

Accessed: 8/25/24

Herbert Butterfield's seminal work, “The Whig Interpretation of History” (1931), launched a scathing attack on the prevailing historiographical approach of his time. He targeted the tendency of many historians to write history from a Whig or Protestant perspective, which distorted the past to conform to present-day values and ideologies.

Key Criticisms

• Presentism: Butterfield argued that Whig historians imposed their own contemporary concerns and values on the past, rather than seeking to understand events as they unfolded.

• Teleology: He criticized the tendency to view history as a linear progression towards a predetermined goal, such as the triumph of liberty or democracy.

• Lack of historical context: Whig historians often ignored or downplayed the complexities and nuances of the past, instead presenting a simplistic narrative that reinforced their own biases.

Alternative Approach

Butterfield advocated for a more nuanced and contextualized understanding of history. He emphasized the importance of:

• Historical particularity: Seeking to understand events as they were perceived by contemporaries, rather than imposing modern interpretations.

• Complexity: Acknowledging the multifaceted nature of historical events and avoiding simplistic or reductionist narratives.

• Objectivity: Striving for a more neutral and detached approach, untainted by present-day agendas or ideologies.

By challenging the Whig Interpretation, Butterfield’s work has had a lasting impact on historiography, influencing generations of historians to adopt a more critical and contextual approach to understanding the past.

This philosophy appears most clearly in the essays Macaulay wrote for the Edinburgh Review and other publications, which were collected in book form and a steady best-seller throughout the 19th century. But it is also reflected in History; the most stirring passages in the work are those that describe the "Glorious Revolution" of 1688.

Macaulay's approach has been criticised by later historians for its one-sidedness and its complacency. Karl Marx referred to him as a 'systematic falsifier of history'.[43] His tendency to see history as a drama led him to treat figures whose views he opposed as if they were villains, while characters he approved of were presented as heroes. Macaulay goes to considerable length, for example, to absolve his main hero William III of any responsibility for the Glencoe massacre. Winston Churchill devoted a four-volume biography of the Duke of Marlborough to rebutting Macaulay's slights on his ancestor, expressing hope "to fasten the label 'Liar' to his genteel coat-tails".[44]

Legacy as a historian

The Liberal historian Lord Acton read Macaulay's History of England four times and later described himself as "a raw English schoolboy, primed to the brim with Whig politics" but "not Whiggism only, but Macaulay in particular that I was so full of." However, after coming under German influence Acton would later find fault in Macaulay.[45] In 1880 Acton classed Macaulay (with Burke and Gladstone) as one "of the three greatest Liberals".[46] In 1883, he advised Mary Gladstone:

[T]he Essays are really flashy and superficial. He was not above par in literary criticism; his Indian articles will not hold water; and his two most famous reviews, on Bacon and Ranke, show his incompetence. The essays are only pleasant reading, and a key to half the prejudices of our age. It is the History (with one or two speeches) that is wonderful. He knew nothing respectably before the seventeenth century, he knew nothing of foreign history, of religion, philosophy, science, or art. His account of debates has been thrown into the shade by Ranke, his account of diplomatic affairs, by Klopp. He is, I am persuaded, grossly, basely unfair. Read him therefore to find out how it comes that the most unsympathetic of critics can think him very nearly the greatest of English writers…[47]

In 1885, Acton asserted that:

We must never judge the quality of a teaching by the quality of the Teacher, or allow the spots to shut out the sun. It would be unjust, and it would deprive us of nearly all that is great and good in this world. Let me remind you of Macaulay. He remains to me one of the greatest of all writers and masters, although I think him utterly base, contemptible and odious for certain reasons which you know.[48]

In 1888, Acton wrote that Macaulay "had done more than any writer in the literature of the world for the propagation of the Liberal faith, and he was not only the greatest, but the most representative, Englishman then living".[49]

W. S. Gilbert described Macaulay's wit, "who wrote of Queen Anne" as part of Colonel Calverley's Act I patter song in the libretto of the 1881 operetta Patience. (This line may well have been a joke about the Colonel's pseudo-intellectual bragging, as most educated Victorians knew that Macaulay did not write of Queen Anne; the History encompasses only as far as the death of William III in 1702, who was succeeded by Anne.)

Herbert Butterfield's The Whig Interpretation of History (1931) attacked Whig history. The Dutch historian Pieter Geyl, writing in 1955, considered Macaulay's Essays as "exclusively and intolerantly English".[50]

On 7 February 1954, Lord Moran, doctor to the Prime Minister, Sir Winston Churchill, recorded in his diary:

Randolph, who is writing a life of the late Lord Derby for Longman's, brought to luncheon a young man of that name. His talk interested the P.M. ... Macaulay, Longman went on, was not read now; there was no demand for his books. The P.M. grunted that he was very sorry to hear this. Macaulay had been a great influence in his young days.[51]

George Richard Potter, Professor and Head of the Department of History at the University of Sheffield from 1931 to 1965, claimed "In an age of long letters ... Macaulay's hold their own with the best".[52] However Potter also claimed:

For all his linguistic abilities he seems never to have tried to enter into sympathetic mental contact with the classical world or with the Europe of his day. It was an insularity that was impregnable ... If his outlook was insular, however, it was surely British rather than English.[53]

With regards to Macaulay's determination to inspect physically the places mentioned in his History, Potter said:

Much of the success of the famous third chapter of the History which may be said to have introduced the study of social history, and even ... local history, was due to the intense local knowledge acquired on the spot. As a result it is a superb, living picture of Great Britain in the latter half of the seventeenth century ... No description of the relief of Londonderry in a major history of England existed before 1850; after his visit there and the narrative written round it no other account has been needed ... Scotland came fully into its own and from then until now it has been a commonplace that English history is incomprehensible without Scotland.[54]

Potter noted that Macaulay has had many critics, some of whom put forward some salient points about the deficiency of Macaulay's History but added: "The severity and the minuteness of the criticism to which the History of England has been subjected is a measure of its permanent value. It is worth every ounce of powder and shot that is fired against it." Potter concluded that "in the long roll of English historical writing from Clarendon to Trevelyan only Gibbon has surpassed him in security of reputation and certainty of immortality".[55]

Piers Brendon wrote that Macaulay is "the only British rival to Gibbon."[56] In 1972, J. R. Western wrote that: "Despite its age and blemishes, Macaulay's History of England has still to be superseded by a full-scale modern history of the period."[57] In 1974 J. P. Kenyon stated that: "As is often the case, Macaulay had it exactly right."[58]

W. A. Speck wrote in 1980, that a reason Macaulay's History of England "still commands respect is that it was based upon a prodigious amount of research".[59] Speck claimed:

Macaulay's reputation as an historian has never fully recovered from the condemnation it implicitly received in Herbert Butterfield's devastating attack on The Whig Interpretation of History. Though he was never cited by name, there can be no doubt that Macaulay answers to the charges brought against Whig historians, particularly that they study the past with reference to the present, class people in the past as those who furthered progress and those who hindered it, and judge them accordingly.[60]

According to Speck:

[Macaulay too often] denies the past has its own validity, treating it as being merely a prelude to his own age. This is especially noticeable in the third chapter of his History of England, when again and again he contrasts the backwardness of 1685 with the advances achieved by 1848. Not only does this misuse the past, it also leads him to exaggerate the differences.[60]

On the other hand, Speck also wrote that Macaulay "took pains to present the virtues even of a rogue, and he painted the virtuous warts and all",[61] and that "he was never guilty of suppressing or distorting evidence to make it support a proposition which he knew to be untrue".[62] Speck concluded:

What is in fact striking is the extent to which his History of England at least has survived subsequent research. Although it is often dismissed as inaccurate, it is hard to pinpoint a passage where he is categorically in error ... his account of events has stood up remarkably well ... His interpretation of the Glorious Revolution also remains the essential starting point for any discussion of that episode ... What has not survived, or has become subdued, is Macaulay's confident belief in progress. It was a dominant creed in the era of the Great Exhibition. But Auschwitz and Hiroshima destroyed this century's claim to moral superiority over its predecessors, while the exhaustion of natural resources raises serious doubts about the continuation even of material progress into the next.[62]

In 1981, J. W. Burrow argued that Macaulay's History of England:

... is not simply partisan; a judgement, like that of Firth, that Macaulay was always the Whig politician could hardly be more inapposite. Of course Macaulay thought that the Whigs of the seventeenth century were correct in their fundamental ideas, but the hero of the History was William, who, as Macaulay says, was certainly no Whig ... If this was Whiggism it was so only, by the mid-nineteenth century, in the most extended and inclusive sense, requiring only an acceptance of parliamentary government and a sense of gravity of precedent. Butterfield says, rightly, that in the nineteenth century the Whig view of history became the English view. The chief agent of that transformation was surely Macaulay, aided, of course, by the receding relevance of seventeenth-century conflicts to contemporary politics, as the power of the crown waned further, and the civil disabilities of Catholics and Dissenters were removed by legislation. The History is much more than the vindication of a party; it is an attempt to insinuate a view of politics, pragmatic, reverent, essentially Burkean, informed by a high, even tumid sense of the worth of public life, yet fully conscious of its interrelations with the wider progress of society; it embodies what Hallam had merely asserted, a sense of the privileged possession by Englishmen of their history, as well as of the epic dignity of government by discussion. If this was sectarian it was hardly, in any useful contemporary sense, polemically Whig; it is more like the sectarianism of English respectability.[63]

In 1982, Gertrude Himmelfarb wrote:

[M]ost professional historians have long since given up reading Macaulay, as they have given up writing the kind of history he wrote and thinking about history as he did. Yet there was a time when anyone with any pretension to cultivation read Macaulay.[64]

Himmelfarb also laments that "the history of the History is a sad testimonial to the cultural regression of our times".[65]

In the novel Marathon Man and its film adaptation, the protagonist was named 'Thomas Babington' after Macaulay.[66]

In 2008, Walter Olson argued for the pre-eminence of Macaulay as a British classical liberal.[67]

Works

• Works by Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay at Project Gutenberg

• Lays of Ancient Rome originally published in the year 1842.