Inside Tibet

by Office of Strategic Services

1943

Freda Bedi Cont'd (#3)

Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#3)

Central Social Welfare Board (CSWB), Excerpt from Social Welfare Administration in India

by Dr. Shradha Chandra

2017

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

[Dr. Shradha Chandra, PhD, is Assistant Professor in the Department of Public Administration, University of Lucknow, India. Author of many scholarly publications and research articles in the field of Public Administration with specialization in Social Welfare Administration. Dr. Chandra has been consistently engaged in teaching at Post-graduation level, supervising PhD's and working on various research projects of National importance.]

The Central Social Welfare Board was established in 1953 by a Resolution of Govt. of India to carry out welfare activities for promoting voluntarism, providing technical and financial assistance to the voluntary organisations for the general welfare of family, women and children. This was the first effort on the part of the Govt. of India to set up an organization, which would work on the principle of voluntarism as a non-governmental organization. The objective of setting up Central Social Welfare Board was to work as a link between the government and the people.

Dr. Durgabai Deshmukh was the founder Chairperson of the Central Social Welfare Board. Earlier she was in charge of "Social Services" in the Planning Commission and she was instrumental in planning the welfare programmes for the First Five Year Plan. Under the guidance of Dr. Durgabai Deshmukh, various welfare schemes were introduced by the Central Social Welfare Board.

The Central Social Welfare Board obtained its legal status in 1969. It was registered under section 25 of the Indian Companies Act, 1956

The State Social Welfare Boards were set up in 1954 in all States and Union Territories. The objective for setting up of the State Social Welfare Boards was to coordinate welfare and developmental activities undertaken by the various Departments of the State Govts. to promote voluntary social welfare agencies for the extension of welfare services across the country, specifically in uncovered areas. The major schemes being implemented by the Central Social Welfare Board were providing comprehensive services in an integrated manner to the community.

Many projects and schemes have been implemented by the Central Social Welfare Board like Grant in Aid, Welfare Extension Projects, Mahila Mandals, Socio Economic Programme, Dairy Scheme, Condensed Course of Education Programme for adolescent girls and women, Vocational Training Programme, Awareness Generation Programme, National Creche Scheme, Short Stay Home Programme, Integrated Scheme for Women's Empowerment for North Eastern States, Innovative Projects and Family Counselling Centre Programme.

The scheme of Family Counselling Centre was introduced by the CSWB in 1983. The scheme provides counselling, referral and rehabilitative services to women and children who are the victims of atrocities, family maladjustments and social ostracism and crisis intervention and trauma counselling in case of natural/ manmade disasters. Working on the concept of people’s participation, FCCs work in close collaboration with the Local Administration, Police, Courts, Free Legal Aid Cells, Medical and Psychiatric Institutions, Vocational Training Centres and Short Stay Homes.

Over six decades of its incredible journey in the field of welfare, development and empowerment of women and children, CSWB has made remarkable contribution for the weaker and marginalized sections of the society. To meet the changing social pattern, CSWB is introspecting itself and exploring new possibilities so that appropriate plan of action can be formulated. Optimal utilisation of ICT facilities will be taken so that effective and transparent services are made available to the stakeholders.

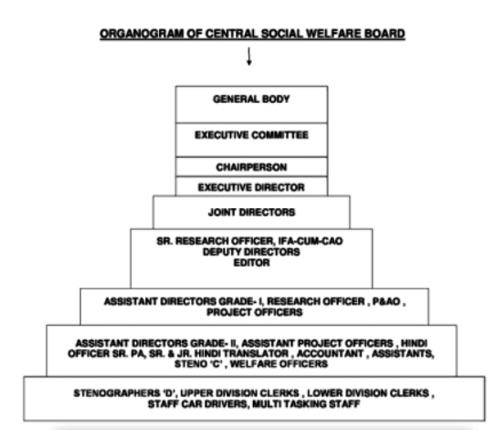

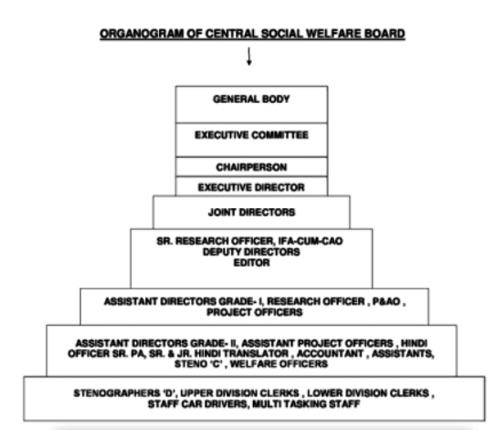

Organogram of Central Social Welfare Board

Composition of CSWB

General Body of the Central Social Welfare Board

As per Memorandum and Articles of Association, there is provision of General Body and Executive Committee for conducting the business of Central Social Welfare Board. The General Body is headed by the Chairperson of the Central Social Welfare Board, it consists of all Chairpersons of the State Social Welfare Boards, five(5) professionals, one each from Law, Medicine, Nutrition, Social Work, Education and Social Development, three (3) eminent social workers, representatives of Govt. of India from Ministry of Women & Child Development, Rural Development, Health & Family Welfare, Finance, NITI Aayog etc. and two (2) members from Lok Sabha and one (1) from Rajya Sabha and Executive Director of Central Social Welfare Board.

Executive Committee of Central Social Welfare Board

The Executive Committee is headed by the Chairperson of the Central Social Welfare Board. Chairpersons of five (5) State Social Welfare Boards including one (1) from the Union Territory, State Board, one representative each from Ministry of Women & Child Development, Rural Development, Finance, Health & Family Welfare, Education and two (2) Professionals from the General Body.

Issue of notification

Notification for the constitution of the Central Social Welfare Board is issued by the Ministry of Women & Child Development, Govt. of India.

Functions and Activities

The Central Social Welfare Board is the key organisation in the field of social welfare in India. Created in 1953 it comprises of a full-time chairperson and members representing state and union territories. Its general body consists of 51 members headed by the chairperson. She is appointed by the government in consultation with the ministry of social welfare from amongst prominent women social workers.

The general body consists of representatives nominated by state governments, social scientists, representatives from the ministries of finance, rural reconstruction, health education and social welfare and one member from Planning Commission. In addition three members of Parliament, social workers, social scientists and social welfare administrators are also included in the general body.

The administration of the affairs of the CSWB is vested in an executive committee nominated by the government from amongst the members of the CSWB. The executive committee comprises of 15 members including the executive director. The Board is administratively organised in a number of divisions and sections.

The chairman is aided by a secretary who is of the rank of the deputy secretary or director in the Government of India. The CSWB has three joint directors, one financial advisor-cum-chief accounts officer, chief administrative officer and a public relations officer. The board assists in the improvement and development of social welfare activities.

Its statutory functions are:

(i) To survey the need and requirements of social welfare organisations.

(ii) To promote the setting up of social welfare institutions in remote areas.

(iii) To promote programmes of training and organize pilot projects in social work.

(iv) To subsidies hostels for working women and the blind.

(v) To give grants-in-aid to voluntary institutions and NGOs providing welfare service to vulnerable sections of society.

(vi) To coordinate assistance extended to welfare agencies by Union and state governments.

The board coordinates between the programmes of the CSWB and other departments and also, between voluntary organisations and the governments. It is funded by the Government of India and the funds for the programmes as well as non-plan expenditure of the board are a part of the budget of the department of social welfare. There has been a significant increase in the total expenditure in the programmes of the board during last few decades.

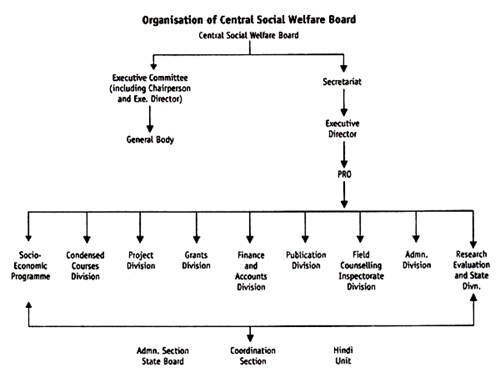

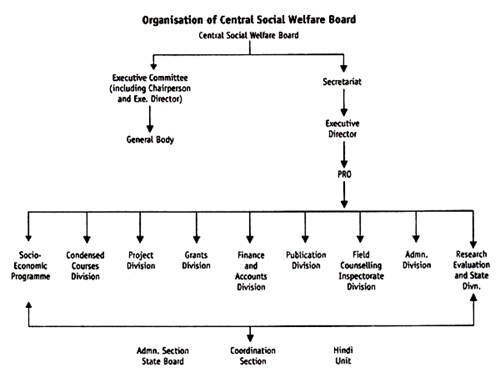

Organisation:

The nine divisions, two sections and one unit which constitute the organisation. The names of the division are self-explanatory. For instance, project division looks after projects while grants-in-aids division processes and administers the distribution of grants the accounts of which are submitted to the finance and accounts division. Coordination and administration of state boards are handled by sections and Hindi unit is for assistance to all the divisions and their units in the field.

The state social welfare boards have a similar and parallel structure but the regional and state variations exist in northern and southern states. The state social welfare boards have been established purely as advisory boards to advise the CSWB on the institutions requiring assistance and their eligibility to get such assistance, while the grants were sanctioned directly to the organisations by the CSWBs.

Organisation of Central Social Welfare Board

These boards are also responsible to supervise, guide and advise the voluntary organisations in the welfare programmes in their respective areas. The CSWB has a wide network of its activities ranging from anganbaris to family welfare camps.

Some of these welfare activities of the target groups are:

(i) Running of rehabilitation centres and cooperative societies for destitute, widows, orphans and deserted women and children.

(ii) Educating and training women to acquire vocational skills to become employable.

(iii) Organising family welfare camps to promote small family norm through opinion leads.

(iv) Providing hostels for working women of low income groups with adequate security.

(v) Operating urban welfare centres in towns for recreational activities and learning programmes for women and children.

(vi) Supplying nutritional supplementary diet and tonics to malnourished mothers and children below 5 years through balwadis and day care centres.

The CSWB consolidates the work done by voluntary agencies. It funds specific projects and strengthens welfare services for children, women and handicapped. The victims of drug abuse, infirm and retarded children and vulnerable groups of minorities are offered extra protection by the programmes of the ministry which directly as well as indirectly contribute to empowerment of the deprived.

by Dr. Shradha Chandra

2017

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Burma was Freda Bedi's gateway to Buddhism -- her assignment there changed her life utterly. She found a teacher, a faith, a form of meditation, and had a moment of awakening which marked a personal turning point. When she returned to India she not only regarded herself as a Buddhist but had decided that her life had a new purpose. Her encounter with Buddhism was more by chance than design. She had for some years been a spiritual seeker -- persisting with her regular meditation sessions and taking up yoga as well. But of the world's four major faiths, Buddhism was the one to which she had been least exposed. She had reviewed a children's storybook based on the Jataka -- an early Buddhist work about the birth tales of the Buddha -- and read from it to Ranga. It stayed with her. Several years later, she wrote about the Buddha's various incarnations, weaving this into her reflections on war, famine and death. She had read Buddhist texts along with other spiritual classics which she found so rewarding. But her visit to Burma was, in so many ways, a revelation. It was her first time immersed in a Buddhist culture and she felt instinctively 'that was my home. Then I knew that in some former life, I think in many former lives, I'd been in the Buddhist way. That's what I feel,' she told a California radio station, while adding 'of course it may be wrong.'

It was money more than spiritual considerations that attracted Freda to Burma. Towards the close of the Bedis' time in Kashmir, she accepted a six months' United Nations posting to Burma, which had won its independence from Britain a year after India. She could probably sense that her husband wouldn't continue for much longer at Sheikh Abdullah's side, and the family needed an income. Her family also needed a home, and before taking up the post Freda had to ensure that her children were cared for. Freda had travelled a great deal but usually with one or other of her children in tow. This was the first time that she had made a long trip leaving all her family behind. Ranga was eighteen and at college in Delhi; Kabir and Guli were much younger, seven and three. She decided against leaving them in the care of her husband, and arranged for them to stay in Delhi with a Czechoslovak friend, Jana Obersal.

Freda's new role with the United Nations was to help in the planning of Burma's social services: 'A job after my own heart,' she told Olive Chandler, 'but it's hard not to be with the family. However, in their interest, I can't throw opportunities away + this opens new fields for us all.' She was restless by nature and relished the opportunity of working somewhere new. 'Burma is like India enough to be homely,' she wrote, 'unlike enough to be beguiling.' Without family responsibilities, she had more time to devote to her own interests, and above all to meditate. She met a Buddhist teacher in Rangoon, U Titthila, who had spent the war years in London where he had on occasions abandoned his monk's robes to serve as an air raid warden and, during the Blitz when London came under sustained German air attack, as a stretcher bearer. Freda found him 'very saintly'; she asked him to teach her Vipassana (insight) meditation techniques. 'And it was then ... I got my first flash of understanding -- can't call it more than that. But it changed my whole life. I felt that, really, this meditation had shown me what I was trying to find ... and I got great, great happiness-a feeling that I had found the path.'

While Vipassana meditation dates back many centuries, the Vipassana movement -- which developed particularly in Burma in the mid-twentieth century -- was an adaptation of earlier teaching. It was innovative and linked broadly to rising anti-colonial sentiment. The meditation technique was intended mainly for lay people and offered quick results (some see it as shaping the more recent mindfulness movement) but because of its intensity, it could on occasions overwhelm new practitioners. For Freda, it brought an early moment of illumination -- one which was life-changing but also destabilising.

For two months, she had a weekly session with U Titthila. 'And I remember him saying when the eight weeks was coming to an end: if you get a realisation or a flash of realisation, it may not be sitting in your room in meditation, in pose in front of a picture of the Buddha or something, it will probably be somewhere where you don't expect it.' That's exactly what happened. 'I was actually walking with the [UN] commission through the streets of Akyab in the north of Burma -- [it was] as though some gates in my mind had just opened and suddenly I was seeing the flow of things, meaning, connections. And when I went back to Delhi, well, I told my husband I'd been searching all my life, it's the Buddhist monks who have been able to show me something I could not find and I'm a Buddhist from now on. Then I began to learn Buddhism after that.' Her family's recollection is that this 'flash' of spiritual awakening was accompanied by a breakdown. According to Ranga, his mother fainted and was taken to hospital. Bedi managed to get emergency travel documents, headed out to Burma and brought his wife home. When she came back, she didn't recognise B.P.L. or anybody. She didn't recognise her children. She would sit on her cot doing nothing -- completely blank. You couldn't make eye contact with her,' Ranga recalls. 'There was no speech, no recognition -- though she could eat and bathe. That lasted for about two months when she gradually started reacting to things. All she recalled was that when walking down the street ... she saw a huge flash of light in the sky and she lost consciousness.'

This was a moment of epiphany -- an incident which redefined her life and purpose. From then on, she regarded herself as a Buddhist. And this was much more than simply a religious allegiance. It quickly became the most important aspect of her life. On her return to Delhi, she set up an organisation that she called the Friends of Buddhism. She took a personal vow of brahmacharya, a commitment to virtuous living which implies a decision to become celibate. Her engagement with the faith radically refashioned her links with her family and set her on the course which defined the last quarter-of-a- century of her life. The household faced several concurrent crises. Freda's collapse not only raised concerns about her health; it also brought an end to any prospect of a longer-term UN role in Burma or indeed anywhere else. Bedi's hasty exit from Kashmir had closed the door on the only regular, decently paid job he ever secured, and plunged him into the much more uncertain arena of small-scale publishing and writing and translating on commission. 'That was a very traumatic move,' Kabir recalls, 'suddenly overnight we arrived in Delhi.' Their reduced circumstances were reflected in the family's accommodation in the Indian capital. From the relative grandeur of a house close to Dal Lake, they took a flat -- a 'grotty' apartment, in Kabir's words -- in the crowded Karol Bagh area of central Delhi. It was quite a comedown.

Once she was fully recovered, Freda again had to take on the responsibility of being the family's primary earner. She got a helping hand from a well-placed friend. Among her papers is a handwritten note from 'Indu', Indira Gandhi, on the headed paper of the Prime Minister's House: 'Durgabai Deshmukh wants to see you at 11 a.m. tomorrow ... in her office in the Planning Commission, Rashtrapati Bhawan. I shall send the car at 10.30.' Deshmukh was an influential figure in the Congress Party and had been a member of India's Constituent Assembly. She had just been appointed as the initial chairperson of the Planning Commission, which in Nehruvian India with its faith in the state to engineer social and economic progress was an important post. She was adamant on the need to champion the interests and promote the welfare of women, children and the disabled. Her meeting with Freda clearly went well. The following month, in January 1954, Freda began working for the government's Central Social Welfare Board establishing and editing a monthly journal, Social Welfare. Although she was not a natural civil servant, she embraced the social agenda and the opportunity to travel across India and throw a spotlight on women's concerns and on projects which successfully addressed them. She remained in the job for eight years.

Freda's government employment wasn't particularly well paid, but it allowed the family a measure of financial security. They moved from Karol Bagh and by the close of 1954 were living in the more comfortable locality of Nizamuddin East: 'a nice house (for Delhi) in the shadow of a Mogul wall, near the beautiful Humayun's Tomb,' she told her old friend Olive Chandler. It was only a temporary respite. For a while the family lived under canvas at a Buddhist centre at Mehrauli just outside Delhi but eventually Freda was allocated government accommodation in the middleclass district of Moti Bagh. She described it as 'one of those nicely tailored modern flats complete with fans and shower-baths. To be frank, it doesn't suit us at all even though it has got its points in terms of comfort. We are a nice sprawly joint family, equipped on the male side with booming Punjabi voices, and hardly fit into a flat at all.' Money was tight. Freda travelled to work by bus or -- for a while -- on a scooter. She was responsible not only for earning but also for managing the household's finances. She was provident, as you might expect of someone brought up in a non-conformist, north of England household. Bedi was the opposite -- earning infrequently, and splashing out when he did. He was a writer for hire, Kabir says, but his earnings were irregular. 'Papa's style was whenever he got money he would then splurge, buy baskets of mangos for everybody in the family and take us on big treats. That was his way of showing his caring.'...

Although her faith loomed increasingly large in her life, she had a demanding job too. At the Central Social Welfare Board, Freda had a free hand in devising the new monthly publication. Social Welfare launched in April 1954 with Freda named as executive editor and promising to be 'the beginning of a new experience in coordinating social welfare in India.' It was conspicuously well produced and made effective use of black-and-white photos and on occasions bore striking modernist-style covers. The journal's purpose was to support the Board's endeavour to develop 'services for women, children, the delinquent and handicapped and the family as a unit'. Freda occasionally wrote under her own by-line, reporting on projects and initiatives she had visited in different parts of India. Both Binder and his wife Manorma were roped in as occasional contributors. She was able to reprise some of the themes she had introduced in Contemporary India twenty years earlier -- prevailing on Devendra Satyarthi to write on Indian cradle songs, traditional dance, and women's life as reflected in folk song. But the hallmark of the magazine was the focus which it placed on women's issues, including many which rarely appeared in the mainstream press.

In the first year of publication, Social Welfare's agenda was cautious. Once established, it became more adventurous, tackling such themes as deserted wives, family planning, unmarried mothers, trafficking of women and children, and prostitution. It also prompted discussion of the widening career opportunities for women, and published exercises for expectant mothers. Freda enjoyed the opportunity to see something of village life in different parts of India. She described herself as 'somebody who loves the village old and new, and finds happiness there'. Her conviction that the village was the essence of India, and village women the backbone of the nation, remained undimmed. The monthly had the advantage over commercial magazines that it was not vulnerable to dips in circulation or revenue, and the frustration that as a government publication its impact was limited. It was the job that Freda stuck to longer than any other. She saw herself as a social worker as much as an editor and journalist and welcomed the prospect of contributing to independent India's social development.

Some of the missions on behalf of the Social Welfare Board took her to corners of the country which were rarely seen by outsiders. In 1958 she accompanied Indira Gandhi to north-east India, visiting areas which are now in the Indian states of Mizoram, Nagaland, Meghalaya and Arunachal Pradesh. 'Indu' remained a close friend, and perhaps a confidante -- her marriage had also hit problems. Freda's children remember going to eat at Auntie Indu's and attending the birthday parties of Indira's sons, Rajiv and Sanjay. 'Sometimes we would go privately and play with their remarkable collection of trains,' Kabir says. 'They had a wonderful room in the prime minister's house that had these trains around tracks, gifts of foreign dignitaries .... As we got older, we'd go out on the president's estate and ride horses and see movies there or go to the swimming pool or go on car rides together. So it was that kind of fairly close relationship with the Gandhi family.'

Freda's government role allowed plenty of opportunity for the networking at which she excelled. Among her new friends was Tara All Baig, a prominent social worker from a privileged background who became the president of the Indian Council of Child Welfare. Baig first met her at a United Nations Youth Conference at Simla, and was struck by both her appearance and personality...

Freda's involvement with Buddhism introduced her to several rich and influential Punjabi women who shared her interest. Goodie Oberoi had married into the family that ran one of India's leading chains of luxury hotels. The Maharani of Patiala was part of a Sikh royal family which retained its political influence after the dissolution of the princely states. In 1957, Freda travelled to Britain at the maharani's request -- her first visit for a decade -- to accompany her two daughters to their new boarding school. She took the opportunity to visit her mother and brother in Derby and see old friends. Freda saw no inconsistency in championing the interests of poor village women and accepting the patronage of the moneyed elite...

Towards the close of 1956, Delhi hosted a major international Buddhist gathering that was Freda's introduction to the Tibetan schools of Buddhism, which are in the Mahayana tradition as distinct from the Theravada school which is predominant in Burma. This Buddha Jayanti was to celebrate the 2,500th anniversary of the Buddha's life. The Indian government wanted Tibet's Buddhist leaders to attend, particularly the Dalai Lama, who was that rare combination of temporal ruler and spiritual leader of his people. The Chinese authorities initially said no but at the last minute relented. Jawaharlal Nehru was at Delhi airport to welcome the twenty-one year old Dalai Lama on his first visit to India; the young Tibetan leader had at this stage not made up his mind whether he would return to his Chinese-occupied homeland or lead a Tibetan independence movement in exile. Freda played a role in welcoming the Tibetan delegation to the Indian capital. 'The radiance and good humour of the Dalai Lama was something we shall never forget,' she told Olive Chandler. 'I also got a chance of shepherding the official tour of the International delegates to India's Buddhist shrines and made many new friends.' A snatch of newsreel footage shows Freda Bedi at the side of the Dalai Lama at Ashoka Vihar, the Buddhist centre outside Delhi where the Bedi family had camped out a few years earlier. Both Kabir and Guli were also there, the latter peering out nervously between a heavily garlanded Dalai Lama and her sari-clad mother. Freda also received the Dalai Lama's blessing.

In the following year, when she made a brief visit to Britain, Freda made a point of visiting the main Buddhist centres in London and meeting Christmas Humphreys, a judge who was the most prominent of the tiny band of converts to Buddhism in Britain. She was becoming well-known and well-connected as a practitioner of Buddhism. What prompted her to become not simply a devotee but an activist once more was the Dalai Lama's second visit to India -- in circumstances hugely different from his first. Nehru had dissuaded the Dalai Lama from staying in India after the Buddha Jayanti celebrations. Early in 1959, Tibet rose up against Chinese rule, an insurrection which provoked a steely response. The Dalai Lama and his retinue, fearing for their lives and for Tibet's Buddhist traditions and learning, fled across the Himalayas, crossing into India at the end of March and reaching the town of Tezpur in Assam on 18th April 1959. Tens of thousands of Tibetans followed the Dalai Lama, undergoing immense hardships as they traversed across the mountains and sought to evade the Chinese army. Freda felt impelled to get involved.

'Technically, I was Welfare Adviser to the Ministry,' Freda wrote of her time at the Tibetan refugee camps in north-east India; 'actually I was Mother to a camp full of soldiers, lamas, peasants and families.' It was a role she found fulfilling. Freda was able to use the skills and contacts she had developed as a social worker and civil servant and at the same time to be nourished by the spirituality evident among those who congregated in the camps. The needs of the refugees were profound. For many, the journeys had been harrowing -- avoiding Chinese troops, travelling on foot across the world's most daunting mountain range and sometimes reduced to eating yak leather to stave off starvation. Many failed to complete the journey. And while the Indian camps offered sanctuary, they were insanitary, overcrowded and badly organised. For hundreds of those who arrived tattered, malnourished and vulnerable to disease, the camps were places to die.

In October 1959, six months after the camps were set up, Jawaharlal Nehru, India's prime minister, asked Freda to visit them and report back -- though it may be more accurate to say that Freda badgered her old friend into giving her this role. Among Delhi's Buddhists, who had welcomed the Dalai Lama so reverently three years earlier, the plight of those who had followed in his footsteps over the mountains would have been of pressing concern. For Freda, it offered her a cause in which to immerse herself as well as an opportunity to deepen her spiritual engagement.

As soon as she reached the camps, Freda realised the urgent and profound humanitarian crisis that was engulfing the thousands of Tibetans who had made it into India. Within a matter of weeks, she had persuaded the government to keep her in the camps for six months as welfare adviser for Tibetan refugees. She took on this role as a secondment to the Ministry of External Affairs -- the refugees and their camps were on Indian soil, but given the intense diplomatic sensitivities of offering refuge to such large numbers of Tibetans, the foreign ministry led on the response to the influx. 'I stayed 6 months in a bamboo hut rehabilitating + looking after refugees,' Freda wrote to her old friend Olive Chandler at the close of the assignment. 'It is an experience too deep to translate into an Air Letter. The Tibetans are honest, brave + wonderful people; the 5000 Lamas we have inherited contain some of the most remarkable spiritually advanced monks + teachers it has been my privilege to meet.' She became entirely absorbed in the lives and welfare of the refugees, and of the Buddhist practice of the monks, nuns and lamas among them. 'I am going back to the [Social Welfare] Board tomorrow,' she told Olive, 'but my heart is in this work.'

Freda's home when working with the refugees was at Misamari camp in Assam, where a former military base -- the American Air Force had been stationed there during the Second World War -- was hastily expanded by the construction of rows of large bamboo huts. Misamari was near the town of Tezpur which the Dalai Lama had reached in mid-April 1959 at the end of his flight across the mountains. By mid-May, the Indian authorities had built shelters at Misamari sufficient for 5,000 refugees -- and it was already clear that would not be sufficient. It was a remote corner of the country -- though not too far as the crow flies from Borhat, still further up the Brahmaputra but on the southern bank, where Ranga and Umi and their young family were living on a tea estate...

The camp may have been safe, but for many Tibetans it was not hospitable. This was alien terrain -- much lower in altitude, stiflingly hot and humid, with a different culture and cuisine. 'Tibetan people don't know [the] language [or] how to make Indian food,' recalled Ayang Rinpoche later one of the most respected Buddhist spiritual teachers in India. He was about sixteen when he arrived at Misamari shortly after the camp opened. 'That place [was] very hot, and underground water [was] very uncomfortable. By this way, Tibetans [were] much suffering and many people died. My mother also died at that place, Misamari.' Another widely revered Buddhist spiritual figure, Ringu Tulku, also reached Misamari in 1959 after a long and arduous journey, 'sometimes fighting, sometimes running, sometimes hiding', from Kham in eastern Tibet. He was about seven years old, and recalls the long bamboo sheds at the camp, each providing shelter to scores of people. 'And very, very hot, so we couldn't usually sleep at night. So we sang and danced all night -- and then we had a little bit of shower. And then we didn't know how to cook dal; we didn't know how to cook all these vegetables.' He too has vivid recollections of the large numbers who died at Misamari from fever and disease.

Lama Yeshe came across Freda Bedi in his first few weeks at the camp. 'Before that I [had] never seen any white woman in my whole life. But she is a very caring, motherly human being.' Ayang Rinpoche also met Freda for the first time at Misamari; he remembers her as 'an English lady with Indian dress, very active, she work[ed] a lot'. Indeed, she kept herself furiously busy -- arranging, organising, improving the health facilities and the water and food supply and ensuring that there was sufficient baby food and vitamins for the newborn and nursing mothers. This became her life. When she decided to dedicate herself to an issue or a cause, it consumed her. The plight of the women among the refugees was a particular concern as they were so central to the Tibetan family groups and tended to avoid attention even when they desperately needed it. Both Kabir and Gulhima spent several weeks of their school holidays with their mother at Misamari -- not quite what they would have expected to be doing once liberated from their boarding schools in the north Indian hills. 'It was an amazing experience,' Kabir says. 'I remember her telling me that when these refugees arrived from Tibet ... the men would be absolutely shattered, probably fit to be carried. And the women would always be standing. And within days of their arrival, there would be women who would collapse and the men would stand. So it's the women who held them together in that long trek across the Himalayas.'...

Her most immediate task was to remedy the shortcomings in the running of these hastily set-up camps. She used the privileged access she had to India's decision makers. She went straight to the top -- to Nehru. And he listened. In early December, Nehru sent a note to India's foreign secretary, the country's most senior career diplomat, asking for a response to concerns that Freda had brought to the prime minister's notice. He endorsed one of Freda's suggestions, 'the absolute necessity of social workers being attached to the camps'.The normal official machinery (Nehru wrote) is not adequate for this purpose, however good it might be. The lack of even such ordinary things as soap and the inadequacy of clothing etc. should not occur if a person can get out of official routines. But more than the lack of things is the social approach.

What concerned Nehru even more was Freda's complaint of endemic corruption. 'She says that "I am convinced that there is very bad corruption among the lower clerical staff in Missamari [sic]". Heavy bribery is referred to. She suggested in her note on corruption that an immediate secret investigation should take place in this matter.' Nehru ordered action to investigate, and if necessary to remove, corrupt officials. 'It is not enough for the local police to be asked to do it,' he instructed. It's not clear what remedial measures were taken but the interest in the running of the Tibetan camps shown by the prime minister and by his daughter, Indira Gandhi, will have helped to redress the most acute of the problems facing the refugees there.

Freda sought to raise awareness of and money for the Tibetan refugees in other ways. At the end of January 1960, just ahead of the Tibetan New Year, she wrote from Misamari to the Times of India, seeking donations from readers to allow the thousands of refugees on Indian soil to celebrate this religious festival. 'The vast majority of the Tibetan refugees are in Government refugee camps and are living on refugee rations,' she wrote. With very few exceptions they are penniless. If they light sacred lamps (deepa), they will do it by sacrificing their ghee rations for some days together. They need money for ceremonial tea and food, for incense and for community utensils ... The Tibetans are separated from country and often from family. Let us give them a feeling of welcome and belonging. Friendliness is as important as rations.' This was very much part of her approach to refugee welfare and reflected her own personality. For Freda, compassion and concern was as essential in aiding the refugees as food and medicine. The Tibetans needed to be reassured that the bonds of shared humanity embraced them too after the ordeal so many had suffered.

'Misamari was a bamboo village, made up of hefty bamboo huts, over a hundred of them, capable of housing eighty or ninety people,' Freda wrote in her only published account of her time in the Tibetan camps. This was titled 'With the Tibetan Refugees', which was as much a declaration of personal allegiance as a description of her role. She recounted that there had been as many as 12,000 refugees in the camp in mid-1959, but it was always intended to be a transit centre and many moved on after a few weeks. 'By the time I reached Misamari, with its fluttering prayer flags and its Camp Hospital of eighty beds, there were about four thousand still to be rehabilitated before the Camp could be closed.' She was writing for the government magazine she also edited, and this was not the place to raise complaints of corruption and maladministration. But she expressed sensitivity to Tibetan customs and needs...

Freda wrote about the efforts made to educate the young Tibetans and provide vocational training. She made only glancing reference to the deployment of many thousands of Tibetans in road building gangs at a paltry daily rate, and none at all to the most unjust aspect of this close-to forced labour, the separation of large numbers of Tibetan children from their parents...

While based at Misamari, Freda also visited the other principal Tibetan camp, at Buxa just across the state border in West Bengal. This was both more substantial than Misamari and more forbidding. It was initially a fort built of bamboo and wood, but had been rebuilt in stone by the British and used as a detention camp -- and as it was so remote, it housed some of what were seen as the more menacing political detainees. When the buildings were made available to the Tibetans, they were in poor repair. All the same, these were allocated for Tibetan Buddhist monks and spiritual teachers. Freda referred to it rather grandly as a monastic college. And unlike Misamari, which was open for little more than a year, Buxa was intended as a long-term camp. It's estimated that at one time as many as 1,500 Tibetans lived there. Conditions were so poor that many monks contracted tuberculosis but it remained in operation for a decade.

Towards the close of her six months in the camps, Freda Bedi again sought out Nehru, and this time was more insistent about the measures the Indian government needed to take to meet its responsibilities towards the refugees. She wrote to the prime minister to pass on the representations of 'the representatives of the Venerable Lamas and monks of the famous monasteries ... living in Misamari', though the vigour with which she expressed herself -- this was not the temperately worded letter that India's prime minister would be more accustomed to receive -- underlines her own anger at what she saw as the harsh treatment of the Tibetan clerics in particular. Her main concern was the enrolling of Tibetan refugees on road building projects.Roadwork is heaving, exhausting, and nomadic, it is utterly unsuited to monks who have lived for long years in settled monastic communities. They can't 'take it', any more than could our lecturers, or officials, or Ashramites, or university faculties and students. Let us face that fact, and make more determined efforts to rehabilitate them in their own groups on land.

She insisted that those who did not offer to do roadwork were not lazy, and that almost all those in the camps were 'eager and willing to work on land in a settled Community'. And she sought lenience for some of those involved in roadwork who were penalised as 'deserters' when they were forced to leave their duties because rain washed away the roads or had made shelter and food supplies precarious. 'I feel it is not worthy of Gov[ernmen]t to be vindictive when the refugees have already suffered as much in Tibet,' she told Nehru. 'We should be big hearted.'

She warned Nehru that the Indian government's responsibility for Tibetan monks wasn't limited to the 700 or so in Dalhousie in the north Indian hills and the 1,500 which at this date -- March 1960 -- were at Buxa. There were a further 1,200 monks in Misamari and new arrivals expected for some months more, and another 1,500 refugees outside the government camps living in and around the Indian border towns of Kalimpong and Darjeeling and 'in a pitiable condition'. Freda was speaking from personal observation. Her letter concluded with an appeal and a warning, again couched in language that only a personal friend could use to address a prime minister:Panditji, I am specially asking your help as I do not want a residue of over one thousand unhappy lamas and monks to be left on our hands when Misamari closed. Nor do I want to hear totally unfair statements that 'they won't work'. I am sure you will help to clarify matters in Delhi.

Nehru asked his foreign secretary to investigate, who replied with a robust defence of the use of refugees in road-building projects. They were not acting under compulsion, he insisted, and this was a temporary measure while more permanent arrangements were made for accommodation and rehabilitation. And he suggested that some at least of the refugees were work shy, expressing just the sort of view that Freda had insisted was so unjust and uncaring. 'Mrs Bedi complains that we have been hard on the Lamas,' the foreign secretary wrote in a note to Nehru. 'There are various grades of Lamas, from the highly spiritual ones -- the incarnate Lamas -- to those who merely serve as attendents [sic]. Our information now is that having found life relatively easy ... many ordinary people who would otherwise have to earn their living by work, are taking to beads and putting forward claims as Lamas. I feel that some pressure should be brought to bear on this kind of people to do some useful work.'

In her letter to the prime minister, Freda had mused that if Nehru could see the Buxa and Misamari camps, 'I feel you would instinctively realise the major unsolved policy problems here on the spot.' In a testament to her personal sway with India's leader, the following month Nehru did indeed visit Misamari. He spent two hours at the camp, looking round the hospital and seeing Tibetan girls who were being trained in handloom weaving. He addressed a crowd which consisted of almost all the 2,800 Tibetans then at Misamari, assuring them that he would act on an appeal he had received from the Dalai Lama to extend arrangements for educating both the young and adults. There was no greater spur to official attention to the Tibetans' welfare than the prime minister's personal oversight of the issue. And if any had doubted just how much influence Freda held with the prime minister, persuading him to travel across the country to one of its most difficult-to-reach corners demonstrated just how influential and effective she was.

Freda did not let the matter drop. On her return to Delhi in June, she called on the prime minister and in a remarkable demonstration of her moral authority and personal influence, cajoled Nehru to write to one of his top civil servants that same evening to express his disquiet about what he had heard concerning recent ministry instructions.One is the order that all the new refugees, without any screening, should be sent on somewhere for road-making, etc. This seems to me unwise and impracticable. These refugees differ greatly, and to treat them as if they were all alike, is not at all wise. There are, I suppose, senior Lamas, junior Lamas, people totally unused to any physical work etc. ...

Sending people for road-making when they are entirely opposed to it, will probably create dis-affection in the road-making groups which have now settled down more-or-less. I was also told that the mortality rate increases.

It reads almost as if Freda was dictating the prime minister's note. She also prompted Nehru to question a reduction in rations for those in the camps, and to urge the provision of wheat, a much more familiar part of the Tibetan diet, rather than rice. Freda Bedi was, Nehru warned, going to call on the ministry the following day -- and civil servants were urged to take immediate action on these and any other pressing issues she raised. 'I do not want the fairly good record we have set up in our treatment of these refugees,' the prime minister asserted, 'to be spoiled now by attempts at economy or lack of care.'

Nehru's more persistent concern was the impact of providing refuge to the Dalai Lama and so many of his followers on relations with India's powerful eastern neighbour. A steady deterioration in relations eventually led to a short border war in 1962 which -- to Nehru's shock and distress -- China won. In the immediate aftermath of that military setback, Nehru came to address troops at Misamari camp, which had reverted to serving as a military base. Nevertheless, India persisted with its open-door policy for Tibetans, and somewhere between 50,000 and 100,000 refugees followed the Dalai Lama into India. The Dalai Lama and his immediate entourage were settled in the hill town of Dharamsala in north India, which became the headquarters of Tibet's government-in-exile...

Freda found her time in the Assam camps both physically and emotionally draining. On her return to Delhi she was admitted to hospital suffering from heat stroke and exhaustion. It was sufficiently serious for Kabir and Gulhima to be brought down from their boarding school in the hills. The doctors said their presence might lift her spirits. 'She responded well to our being there,' Gull says. 'Initially when we went in to see her she did not respond. But the next day she was sitting up and spoke.' Once recovered, she was determined to have a continuing role promoting the welfare of Tibetan refugees even though she was returning to her government job editing Social Welfare. Reading between the lines of Nehru's missives, Freda seems to have lobbied him on this point. 'If possible, I should like to take advantage of her work in future,' Nehru noted. 'She knows these refugees and they have got to know her. Could we arrange with the Central Social Welfare Board to give her to us for two or three weeks at a time after suitable intervals?'

When Freda confided to her friend Olive Chandler that her heart was in working with the Tibetans, she was saying what was becoming increasingly evident to her colleagues in the Social Welfare Board. 'Freda went to these camps and her heart bled,' according to her friend and colleague Tara All Baig. 'She neglected her work with the Board more and more, travelling to the centres especially in Bengal and Dehra Dun where distress was greatest.' Her boss, the formidable Durgabai Deshmukh, got fed up with Freda's preoccupation with the Tibetan issue to the exclusion of other aspects of her work. She was determined to sack Freda, and only Baig's personal intervention saved her job. 'I was lashed by Durgabai's best legal arguments against retaining her. But Freda had children and needed her job. I weathered the storm and was rewarded with Freda's reinstatement.' She survived in her government post for another couple of years, by which time the pull of working more fully and directly with the lamas among the Tibetan refugees had become compelling...

While on her initial mission at the Tibetan camps in 1959-60, Freda also visited Sikkim where a number of Tibetan monks and refugees had settled. It seems to have been then that she first met the head of the Kagyu lineage, one of the four principal schools within Tibetan Buddhism. The 16th Karmapa Lama had escaped from Tibet through Bhutan in the wake of the Dalai Lama's departure and had moved into his order's long established but near derelict monastery at Rumtek in Sikkim. Apa Pant, a senior Indian official, told Freda that she really couldn't come to Sikkim without calling on the Karmapa. Pant was an Oxford contemporary of the Bedis. He was from a princely family and had an inquiring mind about faith and religion; he went on to be one of India's most senior diplomats. At this stage of his career, Pant was India's political officer covering Sikkim and Bhutan, two small largely Buddhist kingdoms which lay on the hugely sensitive border with China, and also in charge of the four Indian missions in Tibet. Freda was keen to act on her friend's suggestion:[Apa Pant] sent me on horseback -- there was no road at that point up to the monastery. And I remember the journey through the forest and it was most beautiful. As we neared the monastery, His Holiness sent people and a picnic basket full of Tibetan tea and cakes and things to refresh us. It's about twenty miles, the path up to the monastery. And when I went to see him, there he was with a great smile on the top floor of a small country monastery surrounded by birds, he just loves birds. ... There he was with his birds, sitting in his room, not on a great throne but on a carpet with a cushion on it. And just at that time, the Burmese changeover took place and the gates of Burma were shut. And I was feeling a great sense of loss that I can't see my Burmese gurus and so I asked the question that was in my mind that I was saving up to ask my guru when I met him. I asked it of His Holiness. And he gave me just the perfect answer...

At the Misamari camp, Freda got to know two tulkus, reincarnations of venerated spiritual leaders, to whom she became particularly attached: Trungpa Rinpoche had led across the Himalayas the large contingent of Tibetans of which Lama Yeshe was part; Akong Rinpoche was his spiritual colleague and close friend, and Lama Yeshe's brother. Both were part of the Kagyu order. Trungpa, Akong and the small band of refugees who managed to complete their journey reached Misamari at the end of January 1960. Freda was the first Westerner that Trungpa had got to know. They had no common language but they established a firm bond. Freda recognised in Trungpa an exceptional spiritual presence and authority and a willingness to adapt to his new circumstances. Trungpa saw in Freda a woman of integrity and influence who could help him make that journey. 'She extended herself to me as a sort of destined mother and saviour,' he said. Within a short time, Freda was helping Trungpa to learn basic English, the first Tibetan she taught, and he was acting as Freda's informal assistant at the camp, a role which helped to spare him from the prospect of being enlisted in a road building gang. Trungpa and his colleagues were transferred to Buxa camp. Not long after, Trungpa managed to get out of Buxa -- the inmates were not free to come and go as they pleased -- to visit the 16th Karmapa Lama at Rumtek. The Karmapa invited Trungpa to stay and join him in rebuilding both the monastery and establishing the Kagyu tradition in new territory; Trungpa declined and moved on, an unorthodox and almost rebellious act in the deeply hierarchical and deferential culture of Tibetan Buddhism.

Shortly after Freda returned to Delhi and her job editing Social Welfare, Trungpa and Akong turned up at the door of her flat. Trungpa had travelled on from Rumtek to Kalimpong, and sent a message back to Akong in Buxa camp suggesting that they head to Delhi. Trungpa and Akong spoke no Hindi and had nothing to guide them to Freda's home beyond an address written on a slip of paper. They turned up, it seems, unannounced, confident that Mummy-La, the name by which Freda was known to the younger lamas and tulkus, would not turn them away. She didn't. 'This winter finds us in our modern flat in New Delhi to which we have had to attach an overflow summer hut,' Freda told Olive Chandler. 'Two young Lamas (age 20) Tulku Major and Tulku Minor share our home this winter, and spend the time getting adjusted to modern life and learning English. It is a joy to have them with us. We are sure they will get ahead quicker with conversation as soon as the children take them in hand.'

Two young men joining the household put quite a strain on the already cramped government accommodation, and the temporary shelter on the veranda which housed Akong and Trungpa would have been pretty miserable during the monsoon rains and through the chilly, if brief, Delhi winter. They stayed at the Moti Bagh flat for the best part of a year. Kabir Bedi recalls an initial feeling of 'great resentment' at this intrusion on the family home. Some of the induction they received into the 'modern world' was not quite what Freda had in mind. Ranga remembers his father giving the two Tibetans both money and men's shorts, so they could buy treats from the market wearing something less conspicuous than their robes. Trungpa and Akong also acted as a beacon for others -- Akong's younger brother, then known as Jamdrak, moved to Delhi to join them. 'Freda's humble home .. .' her friend Tara Ali Baig recalled, 'was soon full to overflowing with young incarnate Lamas. Whatever simple Indian food there was, was shared ... Regardless of their present plight, these cheerfully robed young people warmed to the affection Freda lavished on them.'...

Nehru had taken a diplomatic risk by hosting the Dalai Lama and tens of thousands of those who followed in his wake. But there was a limit to the amount of official support and funding that could be expected for the refugees' welfare, with the most urgent and unmet need being the upkeep and education of the young lamas.

Freda was entirely comfortable soliciting money and support from the rich and well connected. She had also established links with Buddhist and similar groups in London and elsewhere. Within weeks of returning to Delhi from the camps, she sought to turn her extensive network to the Tibetans' advantage. In mid-August 1960, she wrote a long letter to Muriel Lewis, a California-based Theosophist with whom she had corresponded for several years. Muriel ran the Mothers' Research Group principally for American and Western Theosophists, a network which had an interest both in eastern religions and in parenting issues.I should like to feel that the 'Mothers' Group' was in touch with all I do (Freda wrote). Do you think it would be possible for some of your members to 'Adopt' in a small way -- write to, send parcels to -- these junior lamas? Friendships, even by post, could mean a great deal. We could work out a little scheme, if you are interested. The language barrier is there, but we can overcome it, with the help of friends.

Freda's family had, she recounted, already taken a young lama under their wing.Last year my son [Kabir] 'adopted' one small lama of 12, sent him a parcel of woollen (yellow)clothes, sweets and picture books, soap and cotton cloth. This time when I went to Buxa, Jayong gave me such an excited and dazzling smile. He was brimming over with joy at seeing me again! It is very quiet away from your own country and relations for a small lama with a LOT TO LEARN. It was of course most touching to see the 'Mother-Love' in the faces of the tutor-lamas and servant lamas who look after the young ones. They are very tender with them.

Freda's letter was included in Muriel's research group newsletter and subsequently reprinted by the Buddhist Society in London. This was the founding act of the Tibetan Friendship Group, which quickly established a presence in eight western countries and was the conduit by which modest private funds were raised for the refugees. It outlasted Freda and while the group's purpose was not political, it helped give prominence to the Tibet issue as well as the well-being of the Tibetan diaspora.

At the close of the year, Freda sought to enlist her personal friends in this enterprise. 'Do you think you would like to "adopt" a young Tibetan in a small way ... ' she appealed. Which would you choose -- and of what age? The English learning groups include not only junior lamas, young monks and young soldiers (almost all without families) but schoolboys and schoolgirls, some with no father, some with both parents far away on the roads, almost all very keen to make friends and contacts.' Misamari was by now closed and its former inmates dispersed. Some Tibetans eventually settled in Karnataka in south India, others congregated close to Dharamsala in what was then the Punjab hills and small Tibetan communities took root in many of India's cities. This dispersal added to the urgency of ensuring that the young lamas were not simply herded with the rest of the refugees, but identified and offered spiritual guidance and -- the point which Freda emphasised -- a wider education to ensure that their Buddhist practice could be nurtured outside Tibet in a manner which would allow the wider world access to the spiritual richness that the lamas both represented and bestowed.

-- The Lives of Freda: The Political, Spiritual and Personal Journeys of Freda Bedi, by Andrew Whitehead

[Dr. Shradha Chandra, PhD, is Assistant Professor in the Department of Public Administration, University of Lucknow, India. Author of many scholarly publications and research articles in the field of Public Administration with specialization in Social Welfare Administration. Dr. Chandra has been consistently engaged in teaching at Post-graduation level, supervising PhD's and working on various research projects of National importance.]

The Central Social Welfare Board was established in 1953 by a Resolution of Govt. of India to carry out welfare activities for promoting voluntarism, providing technical and financial assistance to the voluntary organisations for the general welfare of family, women and children. This was the first effort on the part of the Govt. of India to set up an organization, which would work on the principle of voluntarism as a non-governmental organization. The objective of setting up Central Social Welfare Board was to work as a link between the government and the people.

Dr. Durgabai Deshmukh was the founder Chairperson of the Central Social Welfare Board. Earlier she was in charge of "Social Services" in the Planning Commission and she was instrumental in planning the welfare programmes for the First Five Year Plan. Under the guidance of Dr. Durgabai Deshmukh, various welfare schemes were introduced by the Central Social Welfare Board.

The Central Social Welfare Board obtained its legal status in 1969. It was registered under section 25 of the Indian Companies Act, 1956

The State Social Welfare Boards were set up in 1954 in all States and Union Territories. The objective for setting up of the State Social Welfare Boards was to coordinate welfare and developmental activities undertaken by the various Departments of the State Govts. to promote voluntary social welfare agencies for the extension of welfare services across the country, specifically in uncovered areas. The major schemes being implemented by the Central Social Welfare Board were providing comprehensive services in an integrated manner to the community.

Many projects and schemes have been implemented by the Central Social Welfare Board like Grant in Aid, Welfare Extension Projects, Mahila Mandals, Socio Economic Programme, Dairy Scheme, Condensed Course of Education Programme for adolescent girls and women, Vocational Training Programme, Awareness Generation Programme, National Creche Scheme, Short Stay Home Programme, Integrated Scheme for Women's Empowerment for North Eastern States, Innovative Projects and Family Counselling Centre Programme.

The scheme of Family Counselling Centre was introduced by the CSWB in 1983. The scheme provides counselling, referral and rehabilitative services to women and children who are the victims of atrocities, family maladjustments and social ostracism and crisis intervention and trauma counselling in case of natural/ manmade disasters. Working on the concept of people’s participation, FCCs work in close collaboration with the Local Administration, Police, Courts, Free Legal Aid Cells, Medical and Psychiatric Institutions, Vocational Training Centres and Short Stay Homes.

Over six decades of its incredible journey in the field of welfare, development and empowerment of women and children, CSWB has made remarkable contribution for the weaker and marginalized sections of the society. To meet the changing social pattern, CSWB is introspecting itself and exploring new possibilities so that appropriate plan of action can be formulated. Optimal utilisation of ICT facilities will be taken so that effective and transparent services are made available to the stakeholders.

Organogram of Central Social Welfare Board

Composition of CSWB

General Body of the Central Social Welfare Board

As per Memorandum and Articles of Association, there is provision of General Body and Executive Committee for conducting the business of Central Social Welfare Board. The General Body is headed by the Chairperson of the Central Social Welfare Board, it consists of all Chairpersons of the State Social Welfare Boards, five(5) professionals, one each from Law, Medicine, Nutrition, Social Work, Education and Social Development, three (3) eminent social workers, representatives of Govt. of India from Ministry of Women & Child Development, Rural Development, Health & Family Welfare, Finance, NITI Aayog etc. and two (2) members from Lok Sabha and one (1) from Rajya Sabha and Executive Director of Central Social Welfare Board.

Executive Committee of Central Social Welfare Board

The Executive Committee is headed by the Chairperson of the Central Social Welfare Board. Chairpersons of five (5) State Social Welfare Boards including one (1) from the Union Territory, State Board, one representative each from Ministry of Women & Child Development, Rural Development, Finance, Health & Family Welfare, Education and two (2) Professionals from the General Body.

Issue of notification

Notification for the constitution of the Central Social Welfare Board is issued by the Ministry of Women & Child Development, Govt. of India.

Functions and Activities

The Central Social Welfare Board is the key organisation in the field of social welfare in India. Created in 1953 it comprises of a full-time chairperson and members representing state and union territories. Its general body consists of 51 members headed by the chairperson. She is appointed by the government in consultation with the ministry of social welfare from amongst prominent women social workers.

The general body consists of representatives nominated by state governments, social scientists, representatives from the ministries of finance, rural reconstruction, health education and social welfare and one member from Planning Commission. In addition three members of Parliament, social workers, social scientists and social welfare administrators are also included in the general body.

The administration of the affairs of the CSWB is vested in an executive committee nominated by the government from amongst the members of the CSWB. The executive committee comprises of 15 members including the executive director. The Board is administratively organised in a number of divisions and sections.

The chairman is aided by a secretary who is of the rank of the deputy secretary or director in the Government of India. The CSWB has three joint directors, one financial advisor-cum-chief accounts officer, chief administrative officer and a public relations officer. The board assists in the improvement and development of social welfare activities.

Its statutory functions are:

(i) To survey the need and requirements of social welfare organisations.

(ii) To promote the setting up of social welfare institutions in remote areas.

(iii) To promote programmes of training and organize pilot projects in social work.

(iv) To subsidies hostels for working women and the blind.

(v) To give grants-in-aid to voluntary institutions and NGOs providing welfare service to vulnerable sections of society.

(vi) To coordinate assistance extended to welfare agencies by Union and state governments.

The board coordinates between the programmes of the CSWB and other departments and also, between voluntary organisations and the governments. It is funded by the Government of India and the funds for the programmes as well as non-plan expenditure of the board are a part of the budget of the department of social welfare. There has been a significant increase in the total expenditure in the programmes of the board during last few decades.

Organisation:

The nine divisions, two sections and one unit which constitute the organisation. The names of the division are self-explanatory. For instance, project division looks after projects while grants-in-aids division processes and administers the distribution of grants the accounts of which are submitted to the finance and accounts division. Coordination and administration of state boards are handled by sections and Hindi unit is for assistance to all the divisions and their units in the field.

The state social welfare boards have a similar and parallel structure but the regional and state variations exist in northern and southern states. The state social welfare boards have been established purely as advisory boards to advise the CSWB on the institutions requiring assistance and their eligibility to get such assistance, while the grants were sanctioned directly to the organisations by the CSWBs.

Organisation of Central Social Welfare Board

These boards are also responsible to supervise, guide and advise the voluntary organisations in the welfare programmes in their respective areas. The CSWB has a wide network of its activities ranging from anganbaris to family welfare camps.

Some of these welfare activities of the target groups are:

(i) Running of rehabilitation centres and cooperative societies for destitute, widows, orphans and deserted women and children.

(ii) Educating and training women to acquire vocational skills to become employable.

(iii) Organising family welfare camps to promote small family norm through opinion leads.

(iv) Providing hostels for working women of low income groups with adequate security.

(v) Operating urban welfare centres in towns for recreational activities and learning programmes for women and children.

(vi) Supplying nutritional supplementary diet and tonics to malnourished mothers and children below 5 years through balwadis and day care centres.

The CSWB consolidates the work done by voluntary agencies. It funds specific projects and strengthens welfare services for children, women and handicapped. The victims of drug abuse, infirm and retarded children and vulnerable groups of minorities are offered extra protection by the programmes of the ministry which directly as well as indirectly contribute to empowerment of the deprived.

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 40037

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#3)

Servants of the People Society

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 4/23/21

Servants of the People Society (SOPS) (Lok Sevak Mandal) is a non-profit social service organization founded by Lala Lajpat Rai, a prominent leader in the Indian Independence movement, in 1921 in Lahore. The society is devoted to "enlist and train national missionaries for the service of the motherland".

It was shifted to India, following the partition of India in 1947, and functioned from the residence of Lala Achint Ram, a founder member and Lok Sabha, M.P. at 2-Telegraph Lane, New Delhi. In 1960, after the construction of the new building its shifted to Lajpat Bhawan, Lajpat Nagar, in Delhi. Today, it has branches in many parts of India.[1]

History

With an aim to create missionary social worker freedom fighter, Lala Lajpat Rai, founded the organisation in November 1921. It was inaugurated by Mahatma Gandhi, and Lalaji who had donated his bungalow in Lahore to the organisation and his library of over 5000 books, remained its founding President till his death in 1928. Its subsequent Presidents were Purushottam Das Tandon, Balwantrai Mehta, and Lal Bahadur Shastri.[2]

The organization's programs today include providing a forum for farmers to sell their produce in cities, providing artisans from rural areas with a place to sell their services and products in cities. The non-profit is also involved in education and family health campaigns.

Lal Bahadur Shastri, second prime minister of India, was a lifelong member of the society[3]

Notes

1. "Head Office". Servants of the People Society. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

2. Grover, Verinder (1993). Political Thinkers of Modern India: Lala Lajpat Rai. Deep & Deep Publications. pp. 547–. ISBN 978-81-7100-426-3.

3. Shastri's biography by FreeIndia.org

External links

• Official website

• Official Site for the Society

• Tribune India newspaper's write up about the society

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 4/23/21

'The Huts' was the Bedis' address for ten years or so until Partition and the upheaval that accompanied it forced them from Lahore. This was not the sort of place of which Freda's mother would have approved -- 'I think my living in huts would have upset her if she had seen it' -- but it was the home where the family was most content. Life in the huts was both happy and beautiful, as Freda remembered it, with a canopy of trees and, beyond, the mustard fields which were a hallmark of the Punjab countryside. 'Under those trees we designed and got built reed huts with plastered mud floors ... and we didn't have to pay rent because we built it in what was known as the green belt. We cultivated vegetables and had a rose garden and sat out under the trees on the string cots of the Punjab. We had the living complex where a dining room and bedroom combined in one big hut; we had a guest hut; and we had a hut for my mother-in-law and Binder.'3 [ 'Berlin to Punjab 1934-39' audio recording made by Freda Bedi c1976, BFA] Over time, there was a retinue of domestic staff -- a gardener, a cook and a secretary: 'In India,' Freda explained to a friend in England, 'there are always too many servants, because they are so cheap + inefficient!'4 [Freda Bedi to Olive Chandler, 1 and 31 March 1940, BFA]

Without electricity, reading, writing and marking papers in the huts was restricted to daylight hours. Reading 'almost stopped in the house at dusk, which could be pretty early in the winter, later in the summer,' Freda said. 'And I used to read in the early morning hours as we got up with the birds, and that again was say 5 a.m. on summer mornings.' There was no room, however, for the Bedis' large collection of books and periodicals which they had assembled with such care and in the spring of 1938, their 'nice personal Library of about a thousand books' was given to the Servants of the People Society, a nationalist-minded social welfare organisation.5 [Tribune, 25 March 1938]

-- Chapter 5: The Huts Beyond Model Town, Excerpt from The Lives of Freda: The Political, Spiritual and Personal Journeys of Freda Bedi, by Andrew Whitehead

Servants of the People Society (SOPS) (Lok Sevak Mandal) is a non-profit social service organization founded by Lala Lajpat Rai, a prominent leader in the Indian Independence movement, in 1921 in Lahore. The society is devoted to "enlist and train national missionaries for the service of the motherland".

In 1880, Lajpat Rai joined Government College at Lahore to study Law, where he came in contact with patriots and future freedom fighters, such as Lala Hans Raj and Pandit Guru Dutt. While studying at Lahore he was influenced by the Hindu reformist movement of Swami Dayanand Saraswati, became a member of existing Arya Samaj Lahore (founded 1877) and founder editor of Lahore-based Arya Gazette.[7] [His journal Arya Gazette concentrated mainly on subjects related to the Arya Samaj.]

When studying law, he became a firm believer in the idea that Hinduism, above nationality, was the pivotal point upon which an Indian lifestyle must be based. He believed, Hinduism, led to practices of peace to humanity, and the idea that when nationalist ideas were added to this peaceful belief system, a secular nation could be formed...

Since childhood, he also had a desire to serve his country and therefore took a pledge to free it from foreign rule, in the same year he also founded the Hisar district branch of the Indian National Congress and reformist Arya Samaj with Babu Churamani (lawyer), three Tayal brothers (Chandu Lal Tayal, Hari Lal Tayal and Balmokand Tayal), Dr. Ramji Lal Hooda, Dr. Dhani Ram, Arya Samaj Pandit Murari Lal,[9] Seth Chhaju Ram Jat (founder of Jat School, Hisar) and Dev Raj Sandhir...

In 1914, he quit law practice to dedicate himself to the freedom of India and went to Britain in 1914 and then to the United States in 1917. In October 1917, he founded the Indian Home Rule League of America in New York. He stayed in the United States from 1917 to 1920...

Graduates of the National College, which he founded inside the Bradlaugh Hall at Lahore as an alternative to British institutions, included Bhagat Singh.[10] He was elected President of the Indian National Congress in the Calcutta Special Session of 1920...

While in America he had founded the Indian Home Rule League in New York and a monthly journal Young India and Hindustan Information Services Association. He had petitioned the Foreign affairs committee of Senate of American Parliament giving a vivid picture of maladministration of British Raj in India, the aspirations of the people of India for freedom amongst many other points strongly seeking the moral support of the international community for the attainment of independence of India. The 32-page petition which was prepared overnight was discussed in the U.S. Senate during October 1917.[13] The book also argues for the notion of "color-caste," suggesting sociological similarities between race in the US and caste in India.

-- Lala Lajpat Rai, by Wikipedia

It was shifted to India, following the partition of India in 1947, and functioned from the residence of Lala Achint Ram, a founder member and Lok Sabha, M.P. at 2-Telegraph Lane, New Delhi. In 1960, after the construction of the new building its shifted to Lajpat Bhawan, Lajpat Nagar, in Delhi. Today, it has branches in many parts of India.[1]

History

With an aim to create missionary social worker freedom fighter, Lala Lajpat Rai, founded the organisation in November 1921. It was inaugurated by Mahatma Gandhi, and Lalaji who had donated his bungalow in Lahore to the organisation and his library of over 5000 books, remained its founding President till his death in 1928. Its subsequent Presidents were Purushottam Das Tandon, Balwantrai Mehta, and Lal Bahadur Shastri.[2]

"The Society was initially started with the [Bal Gangadhar] Tilak School of Politics in 1921, to train those who would work in the political field. The state of the country during 1921 engendered a war atmosphere in which normal priorities had to be waived. The initiates pledged to serve the Society and were bound only by their word and sense of honor and of duty."

Tilak was one of the first and strongest advocates of Swaraj ("self-rule") and a strong radical in Indian consciousness. He is known for his quote in Marathi: "Swarajya is my birthright and I shall have it!". He formed a close alliance with many Indian National Congress leaders including Bipin Chandra Pal, Lala Lajpat Rai, Aurobindo Ghose, V. O. Chidambaram Pillai and Muhammad Ali Jinnah...

He stated: "Religion and practical life are not different. The real spirit is to make the country your family instead of working only for your own. The step beyond is to serve humanity and the next step is to serve God."..

Tilak was considered a radical Nationalist but a Social conservative...

During late 1896, a bubonic plague spread from Bombay to Pune, and by January 1897, it reached epidemic proportions. British troops were brought in to deal with the emergency and harsh measures were employed including forced entry into private houses, the examination of occupants, evacuation to hospitals and segregation camps, removing and destroying personal possessions, and preventing patients from entering or leaving the city. By the end of May, the epidemic was under control. They were widely regarded as acts of tyranny and oppression. Tilak took up this issue by publishing inflammatory articles in his paper Kesari (Kesari was written in Marathi, and "Maratha" was written in English), quoting the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita, to say that no blame could be attached to anyone who killed an oppressor without any thought of reward. Following this, on 22 June 1897, Commissioner Rand and another British officer, Lt. Ayerst were shot and killed by the Chapekar brothers and their other associates. According to Barbara and Thomas R. Metcalf, Tilak "almost surely concealed the identities of the perpetrators". Tilak was charged with incitement to murder and sentenced to 18 months imprisonment. When he emerged from prison in present-day Mumbai, he was revered as a martyr and a national hero...

On 30 April 1908, two Bengali youths, Prafulla Chaki and Khudiram Bose, threw a bomb on a carriage at Muzzafarpur, to kill the Chief Presidency Magistrate Douglas Kingsford of Calcutta fame, but erroneously killed two women traveling in it. While Chaki committed suicide when caught, Bose was hanged. Tilak, in his paper Kesari, defended the revolutionaries and called for immediate Swaraj or self-rule. The Government swiftly charged him with sedition. At the conclusion of the trial, a special jury convicted him by 7:2 majority...

In passing sentence, the judge indulged in some scathing strictures against Tilak's conduct. He threw off the judicial restraint which, to some extent, was observable in his charge to the jury. He condemned the articles as "seething with sedition", as preaching violence, speaking of murders with approval. "You hail the advent of the bomb in India as if something had come to India for its good. I say, such journalism is a curse to the country". Tilak was sent to Mandalay from 1908 to 1914...While in the prison he wrote the Gita Rahasya...