by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/26/24

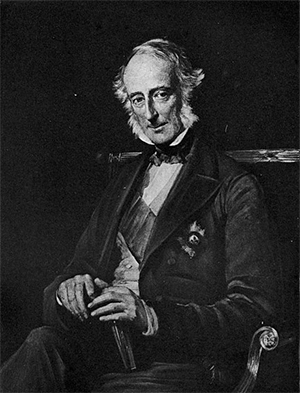

-- Lord William Bentinck, by Wikipedia

-- Thomas Babington Macaulay, by Wikipedia

-- The Whig Interpretation of History, by Herbert Butterfield, M.A., 1965

-- Report of the Indian Education Commission, Appointed by the Resolution of the Government of India dated 3rd February 1882, Calcutta, Printed by the Superintendent of Government Printing, India, 1883

-- William Wilson Hunter, by Wikipedia

-- Indian Education Commission (1882-83), by YourArticleLibrary

-- First Indian Education Commission or the Hunter Commission, by YourArticleLibrary

-- Minute by the Hon'ble T. B. Macaulay, by Thomas Babington Macaulay

English Education Act 1835

Council of India

Enacted by: Council of India

Status: Repealed

The English Education Act 1835 was a legislative Act of the Council of India, gave effect to a decision in 1835 by Lord William Bentinck, then Governor-General of the British East India Company, to reallocate funds it was required by the British Parliament to spend on education and literature in India. Previously, they had given limited support to traditional Muslim and Hindu education and the publication of literature in the then traditional languages of education in India (Sanskrit and Persian); henceforward they were to support establishments teaching a Western curriculum with English as the language of instruction. Together with other measures promoting English as the language of administration and of the higher law courts (instead of Persian, as under the Mughal Empire), this led eventually to English becoming one of the languages of India, rather than simply the native tongue of its foreign rulers.

In discussions leading up to the Act Thomas Babington Macaulay produced his famous Memorandum on (Indian) Education which was scathing on the inferiority (as he saw it) of native (particularly Hindu) culture and learning. He argued that Western learning was superior, and currently could only be taught through the medium of English. There was therefore a need to produce—by English-language higher education—"a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals and in intellect" who could in their turn develop the tools to transmit Western learning in the vernacular languages of India. Among Macaulay's recommendations were the immediate stopping of the printing by the East India Company of Arabic and Sanskrit books and that the company should not continue to support traditional education beyond "the Sanskrit College at Benares and the Mahometan College at Delhi" (which he considered adequate to maintain traditional learning).

The act itself, however, took a less negative attitude to traditional education and was soon succeeded by further measures based upon the provision of adequate funding for both approaches. Vernacular language education, however, continued to receive little funding, although it had not been much supported before 1835 in any case.

British support for Indian learning

When the Parliament had renewed the charter of the East India Company for 20 years in 1813, it had required the company to apply 100,000 rupees per year[1] "for the revival and promotion of literature and the encouragement of the learned natives of India, and for the introduction and promotion of a knowledge of the sciences among the inhabitants of the British territories."[2]

This lac of rupees is set apart, not only for "reviving literature in India," the phrase on which their whole interpretation is founded, but also for "the introduction and promotion of a knowledge of the sciences among the inhabitants of the British territories...."

-- Minute by the Hon'ble T. B. Macaulay, by Thomas Babington Macaulay

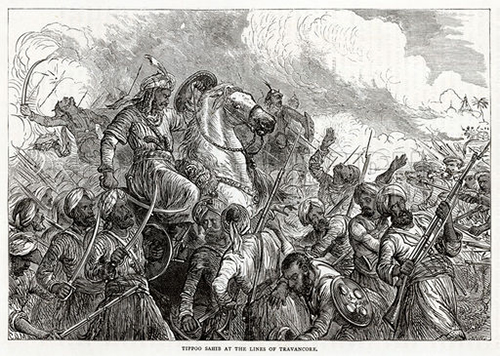

This had gone to support traditional forms (and content) of education, which (like their contemporary equivalents in England) were firmly non-utilitarian. [non-utilitarian: decorative and not designed to be useful (Cambridge Dictionary] In 1813, by the request of Colonel John Munro, the then British Resident of Travancore and Pulikkottil Dionysius II, a learned monk of Orthodox Syrian Church, Gowri Parvati Bayi, the Queen of Travancore granted permission to start a Theological college in Kottayam, Travancore. The queen granted the tax free 16 acre property, ₹ 20,000, and the necessary timber for construction. The foundation stone was laid on 18 February 1813 and the construction completed by 1815. The structure of the Old Seminary Building is called Naalukettu translated into English as central-quadrangle. The early missionaries who worked here – Norton, Henry Baker, Benjamin Bailey and Fenn – rendered remarkable service. Initially called Cottayam College, the Seminary was not exclusively meant for priest training. It was a seat of English general education in the State of Travancore and is regarded as the "first locale to start English education" in Kerala and the first to have Englishmen as teachers in 1815 itself. In course of time it even came to be known as Syrian College. The students were taught English, Hebrew, Greek, Latin, Syriac and Sanskrit over and above Malayalam along with Theological subjects.

By the early 1820s, some administrators within the East India Company were questioning if this was a sensible use of the money. James Mill noted that the declared purpose of the Madrassa (Mohammedan College) and the Hindu College in Calcutta set up by the company had been "to make a favourable impression, by our encouragement of their literature, upon the minds of the natives" but took the view that the [plan] of the company should have been to further not Oriental learning but "useful learning". Indeed, private enterprise colleges had begun to spring up in Bengal teaching Western knowledge in English ("English education"), to serve a native clientele which felt it would be more important that their sons learnt to understand the English than that they were taught to appreciate classic poetry.

Broadly similar issues ('classical education' vs 'liberal education') had already arisen for education in England with existing grammar schools being unwilling (or legally unable) to give instruction in subjects other than Latin or Greek and were to end in an expansion of their curriculum to include modern subjects. In the Indian situation a complicating factor was that the 'classical education' reflected the attitudes and beliefs of the various traditions in the sub-continent, 'English education' clearly did not, and there was felt to be a danger of an adverse reaction among the existing learned classes of India to any withdrawal of support for them.

This led to divided counsels within the Committee of Public Instruction. Macaulay, who was Legal Member of the Council of India, and was to be President of the committee, refused to take up the post until the matter was resolved, and sought a clear directive from the Governor-General on the strategy to be adopted.

It should have been clear what answer Macaulay was seeking, given his past comments. In 1833 in the House of Commons Macaulay (then MP for Leeds),[3] had spoken in favour of renewal of the company's charter, in terms which make his own views on the culture and society of the sub-continent adequately clear:

I see a government[4] anxiously bent on the public good. Even in its errors I recognize a paternal feeling towards the great people committed to its charge. I see toleration strictly maintained. Yet I see bloody and degrading superstitions gradually losing their power. I see the morality, the philosophy, the taste of Europe, beginning to produce a salutary effect on the hearts and understandings of our subjects. I see the public mind of India, that public mind which we found debased and contracted by the worst forms of political and religious tyranny, expanding itself to just and noble views of the ends of government and of the social duties of man.

In the peroration, he emphasized the moral imperative of educating Indians in English ways, not to keep them submissive but to give them the potential eventually to claim the same rights as the English:

What is that power worth which is founded on vice, on ignorance, and on misery—which we can hold only by violating the most sacred duties which as governors we owe to the governed—which as a people blessed with far more than an ordinary measure of political liberty and of intellectual light—we owe to a race debased by three thousand years of despotism and priest craft? We are free, we are civilized, to little purpose, if we grudge to any portion of the human race an equal measure of freedom and civilization.

Are we to keep the people of India ignorant in order that we may keep them submissive? Or do we think that we can give them knowledge without awakening ambition? Or do we mean to awaken ambition and to provide it with no legitimate vent? Who will answer any of these questions in the affirmative? Yet one of them must be answered in the affirmative, by every person who maintains that we ought permanently to exclude the natives from high office. I have no fears. The path of duty is plain before us: and it is also the path of wisdom, of national prosperity, of national honour.

The destinies of our Indian empire are covered with thick darkness. It is difficult to form any conjecture as to the fate reserved for a state which resembles no other in history, and which forms by itself a separate class of political phenomena. The laws which regulate its growth and its decay are still unknown to us. It may be that the public mind of India may expand under our system till it has outgrown that system; that by good government we may educate our subjects into a capacity for better government, that, having become instructed in European knowledge, they may, in some future age, demand European institutions. Whether such a day will ever come I know not. But never will I attempt to avert or to retard it. Whenever it comes, it will be the proudest day in English history. To have found a great people sunk in the lowest depths of slavery and superstition, to have so ruled them as to have made them desirous and capable of all the privileges of citizens would indeed be a title to glory all our own.[5] The sceptre may pass away from us. Unforeseen accidents may derange our most profound schemes of policy. Victory may be inconstant to our arms. But there are triumphs which are followed by no reverses. There is an empire exempt from all natural causes of decay. Those triumphs are the pacific triumphs of reason over barbarism; that empire is the imperishable empire of our arts and our morals, our literature and our laws.

Macaulay's "Minute Upon Indian Education"

To remove all doubt, however, Macaulay produced and circulated a Minute on the subject. Macaulay argued that support for the publication of books in Sanskrit and Arabic should be withdrawn, support for traditional education should be reduced to funding for the Madrassa at Delhi and the Hindu College at Benares, but students should no longer be paid to study at these establishments.[6] The money released by these steps should instead go to fund education in Western subjects, with English as the language of instruction. He summarised his argument

To sum up what I have said, I think it is clear that we are not fettered by the Act of Parliament of 1813; that we are not fettered by any pledge expressed or implied; that we are free to employ our funds as we choose; that we ought to employ them in teaching what is best worth knowing; that English is better worth knowing than Sanskrit or Arabic; that the natives are desirous to be taught English, and are not desirous to be taught Sanskrit or Arabic; that neither as the languages of law, nor as the languages of religion, have the Sanskrit and Arabic any peculiar claim to our engagement; that it is possible to make natives of this country thoroughly good English scholars, and that to this end our efforts ought to be directed.

With Macaulay’s Minute – notes that are recorded during a meeting, highlighting key issues that are discussed, motions proposed or voted on, and certain activities that may need to be acted upon – his efforts were not always perceived in the kindest of light. The proposed “Minute on Education” has had its importance questioned by hundreds of scholars throughout the years, especially Warren Hastings. From 1780 to 1835, the British government in India had followed the educational policy that was in place under Warren Hastings. He wanted to maintain the British East India Company’s stance that they had to do more than the pre-British Muslim governments had done to encourage classes of Muslim and Hindu society. However, Macaulay demotes this policy through his Minute, using it as a final, yet successful, attack upon the Hastings educational policy, speaking to how completing an education should not be rewarded with payment or how the educated should ‘expect any remunerative employment by which they might put their specialized learning to work’. The conflicting viewpoint gathered Macaulay's disdain in the public eye, even to the present day.

Macaulay's comparison of Arabic and Sanskrit literature to what was available in English is forceful, colourful, and nowadays often quoted against him.

I have conversed both here and at home with men distinguished by their proficiency in the Eastern tongues. I am quite ready to take the oriental learning at the valuation of the Orientalists themselves. I have never found one among them who could deny that a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia.[7] [...] And I certainly never met with any Orientalist who ventured to maintain that the Arabic and Sanscrit poetry could be compared to that of the great European nations. But when we pass from works of imagination to works in which facts are recorded, and general principles investigated, the superiority of the Europeans becomes absolutely immeasurable. It is, I believe, no exaggeration to say, that all the historical information which has been collected from all the books written in the Sanscrit language is less valuable than what may be found in the most paltry abridgments used at preparatory schools in England. In every branch of physical or moral philosophy, the relative position of the two nations is nearly the same.

In 1937 and 1938, writers Edward Thompson and Percival Spear argued how Macaulay’s Minute was more “secondhand nonsense” and how the “decisive consideration was financial economy… it was cheaper to teach people to read in English than to subsidize translations in a variety of Indian languages….” With this came the idea of a divide in Indian society on how to approach this new way of thinking. The incorporation of English and Westernized education into traditional education in India was not perceived in the best light by most natives. With there being already a lack of formal education in India, the intrusiveness of incorporating Western concepts made many natives feel that receiving an ‘English education’ in India is entirely different than a ‘desire to learn English’ [?].

There had already been an implementation of English and Western society in India at the time, primarily focused on the East India Company, where speaking English was embedded into everyday use. These native ‘elite’ group of English speakers in India worked in offices, factories, and warehouses of the East India Company, with their numbers increasing rapidly, giving Macaulay more reason to impose the Minutes upon the natives. However, despite the increasing numbers of English speakers and learners in India, there came the ‘Downward Filtration Theory’, where many of the wealthy class – mainly those who studied and practiced English – failed to help improve the lives of those in the lower class. This was largely due to the amount of the lower class that tried to receive a better education, but there were only some ‘students who learned English were [able] to pay’. The more financial stability one had equated to how much of a Western education they received, with the elite and wealthy gaining most of the knowledge. Despite some doing better off in a game of winners and losers, most natives were detrimentally affected by the Minutes, with many being impacted by this drastic shift into ‘westernizing’ of ‘Indian’ cultures.

He returned to the comparison later:

Whoever knows [English] has ready access to all the vast intellectual wealth, which all the wisest nations of the earth have created and hoarded in the course of ninety generations. It may be safely said, that the literature now extant in that language is of far greater value than all the literature which three hundred years ago was extant in all the languages of the world together. [...] The question now before us is simply whether, when it is in our power to teach this language, we shall teach languages in which, by universal confession, there are no books on any subject which deserve to be compared to our own; whether, when we can teach European science, we shall teach systems which, by universal confession, whenever they differ from those of Europe, differ for the worse; and whether, when we can patronise sound Philosophy and true History, we shall countenance, at the public expense, medical doctrines, which would disgrace an English farrier,—Astronomy, which would move laughter in girls at an English boarding school,—History, abounding with kings thirty feet high, and reigns thirty thousand years long,—and Geography, made up of seas of treacle and seas of butter.

Mass education would be (in the fullness of time) by the class of Anglicised Indians the new policy should produce, and by the means of vernacular dialects [??

[...] it is impossible for us, with our limited means, to attempt to educate the body of the people. We must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern; a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect. To that class we may leave it to refine the vernacular dialects of the country, to enrich those dialects with terms of science borrowed from the Western nomenclature, and to render them by degrees fit vehicles for conveying knowledge to the great mass of the population.

What came along with the ‘Westernization of Indian cultures’ was an abandonment of culture and religion. In a letter to his father, Zachary Macaulay detailed the ‘success’ of the Minute, and the impact it had on Indian culture and livelihood since its enactment. He details how “the effect of this education on the Hindoos is prodigious… no Hindoo who has received an English education ever continues to be sincerely attached to his religion….” The shift to Western education, although favored by a majority of the general committee, was not the results that India had expected. The abandonment of some of their religion, changing over to implementing was to fulfill ‘serving the colonial bureaucracy’. Relaying [Relating?] back to how only the elite could receive higher English education, this created the divide that resulted in the major religious and cultural shifts throughout India. [?]

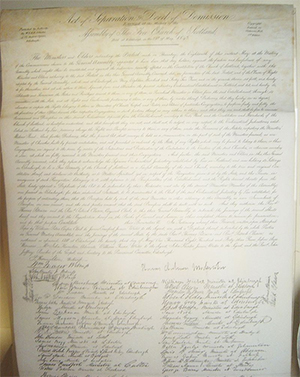

The Act

[url-http://survivorbb.rapeutation.com/viewtopic.php?f=60&t=4204&start=172]Bentinck[/url] wrote that he was in full agreement with the sentiments expressed.[8] However, students at the Calcutta Madrassa raised a petition against its closure; this quickly got considerable support and the Madrassa and its Hindu equivalent were therefore retained. Otherwise the Act endorsed and implemented the policy Macaulay had argued for.

The Governor-General of India in Council has attentively considered the two letters from the Secretary to the Committee of Public Instruction,[9] dated the 21st and 22nd January last, and the papers referred to in them.

First, His Lordship in Council is of opinion that the great object of the British Government ought to be the promotion of European literature and science among the natives of India; and that all the funds appropriated for the purpose of education would be best employed on English education alone.

Second, But it is not the intention of His Lordship in Council to abolish any College or School of native learning, while the native population shall appear to be inclined to avail themselves of the advantages which it affords, and His Lordship in Council directs that all the existing professors and students at all the institutions under the superintendence of the Committee shall continue to receive their stipends. But his lordship in Council decidedly objects to the practice which has hitherto prevailed of supporting the students during the period of their education. He conceives that the only effect of such a system can be to give artificial encouragement to branches of learning which, in the natural course of things, would be superseded by more useful studies and he directs that no stipend shall be given to any student that may hereafter enter at any of these institutions; and that when any professor of Oriental learning shall vacate his situation, the Committee shall report to the Government the number and state of the class in order that the Government may be able to decide upon the expediency of appointing a successor.

Third, It has come to the knowledge of the Governor-General in Council that a large sum has been expended by the Committee on the printing of Oriental works; his Lordship in Council directs that no portion of the funds shall hereafter be so employed.

Fourth, His Lordship in Council directs that all the funds which these reforms will leave at the disposal of the Committee be henceforth employed in imparting to the native population a knowledge of English literature and science through the medium of the English language; and His lordship.

Opposition in London suppressed

On the news of the Act reaching England, a despatch giving the official response of the company's Court of Directors was drafted within India House (the company's London office). James Mill was a leading figure within the India House (as well as being a leading utilitarian philosopher). Although he was known to favour education in the vernacular languages of India, otherwise he might have been expected to be broadly in favour of the Act. However, he was by then a dying man, and the task of drafting the response fell to his son John Stuart Mill. The younger Mill was thought to hold similar views to his father, but his draft despatch turned out to be quite critical of the Act.

Mill argued that students seeking an 'English education' in order to prosper could simply acquire enough of the requisite practical accomplishments (facility in English etc.) to prosper without bothering to acquire the cultural attitudes; for example it did not follow that at the same time they would also free themselves from superstition. Even if they did the current learned classes of India commanded widespread respect in Indian culture, and that one of the reasons they did so was the lack of practical uses for their learning; they were pursuing learning as an end in itself, rather than as a means to advancement. The same could not reliably said of those seeking an 'English education', and therefore it was doubtful how they would be regarded by Indian society and therefore how far they would be able to influence it for the better. It would have been a better policy to continue to conciliate the existing learned classes, and to attempt to introduce European knowledge and disciplines into their studies and thus make them the desired interpreter class. This analysis was acceptable to East India Company's Court of Directors but unacceptable to their political masters (because it effectively endorsed the previous policy of 'engraftment')[?] and John Cam Hobhouse insisted on the despatch being redrafted to be a mere holding statement noting the Act but venturing no opinion upon it. [?]

Aftermath

Reversion to favouring traditional colleges

By 1839 Lord Auckland had succeeded Bentinck as Governor-General, and Macaulay had returned to England. Auckland contrived to find sufficient funds to support the English Colleges set up by Bentinck's Act without continuing to run down the traditional Oriental colleges. He wrote a Minute (of 24 November 1839) giving effect to this; both Oriental and English colleges were to be adequately funded. The East India Company directors responded with a despatch in 1841 endorsing the twin-track approach and suggesting a third:

We forbear at present from expressing an opinion regarding the most efficient mode of communicating and disseminating European Knowledge. Experience does not yet warrant the adoption of any exclusive system. We wish a fair trial to be given to the experiment of engrafting European Knowledge on the studies of the existing learned Classes, encouraged as it will be by giving to the Seminaries in which those studies are prosecuted, the aid of able and efficient European Superintendence. At the same time we authorise you to give all suitable encouragement to translators of European works into the vernacular languages and also to provide for the compilation of a proper series of Vernacular Class books according to the plan which Lord Auckland has proposed.

The East India Company also resumed subsidising the publication of Sanscrit and Arabic works, but now by a grant to the Asiatic Society rather than by undertaking publication under their own auspices.[10]

Mill's later views

In 1861, Mill in the last chapter ('On the Government of Dependencies') of his 'Considerations on Representative Government' restated the doctrine Macaulay had advanced a quarter of a century earlier – the moral imperative to improve subject peoples, which justified reforms by the rulers of which the ruled were as yet unaware of the need for,

"There are ... [conditions of society] in which, there being no spring of spontaneous improvement in the people themselves, their almost only hope of making any steps in advance [to 'a higher civilisation'] depends on the chances of a good despot. Under a native despotism, a good despot is a rare and transitory accident: but when the dominion they are under is that of a more civilised people, that people ought to be able to supply it constantly. The ruling country ought to be able to do for its subjects all that could be done by a succession of absolute monarchs guaranteed by irresistible force against the precariousness of tenure attendant on barbarous despotisms, and qualified by their genius to anticipate all that experience has taught to the more advanced nation. Such is the ideal rule of a free people over a barbarous or semi-barbarous one. We need not expect to see that ideal realised; but unless some approach to it is, the rulers are guilty of a dereliction of the highest moral trust which can devolve upon a nation: and if they do not even aim at it, they are selfish usurpers, on a par in criminality with any of those whose ambition and rapacity have sported from age to age with the destiny of masses of mankind"

but Mill went on to warn of the difficulties this posed in practice; difficulties which whatever the merits of the Act of 1835 do not seem to have suggested themselves to Macaulay:[11]

It is always under great difficulties, and very imperfectly, that a country can be governed by foreigners; even when there is no disparity, in habits and ideas, between the rulers and the ruled. Foreigners do not feel with the people. They cannot judge, by the light in which a thing appears to their own minds, or the manner in which it affects their feelings, how it will affect the feelings or appear to the minds of the subject population. What a native of the country, of average practical ability, knows as it were by instinct, they have to learn slowly, and after all imperfectly, by study and experience. The laws, the customs, the social relations, for which they have to legislate, instead of being familiar to them from childhood, are all strange to them. For most of their detailed knowledge they must depend on the information of natives; and it is difficult for them to know whom to trust. They are feared, suspected, probably disliked by the population; seldom sought by them except for interested purposes; and they are prone to think the servilely submissive are the trustworthy. Their danger is of despising the natives; that of the natives is of disbelieving that anything the strangers do can be intended for their good.[12]

See also

• Education in India

• Indianisation

• Timeline of Hindu texts

References

1. The rupee was then worth about two shillings, so roughly £10,000 (equivalent current purchasing power clearly considerably more)

2. quoted in Macaulay's Minute

3. subsequent financial difficulties had led him to go out to India to rebuild his fortunes

4. that of the East India Company

5. But in an essay of 1825, Macaulay had defended the politics of Milton (objected to by Johnson's Lives of the Poets) on very different lines

Many politicians of our time are in the habit of laying it down as a self-evident proposition, that no people ought to be free till they are fit to use their freedom. The maxim is worthy of the fool in the old story who resolved not to go into the water till he had learnt to swim. If men are to wait for liberty till they become wise and good in slavery, they might indeed wait forever. "Milton", Edinburgh Review, August 1825 ; included in T. B. Macaulay 'Critical and Historical Essays, Vol 1', J M Dent, London, 1910 [Everyman's Library, volume 225]

6. Macaulay described it as unheard of that students should have to be paid to study, but later had to concede that scholarships were routinely awarded at English universities

7. Indeed, a response to the Minute circulated by Henry Thoby Prinsep (also to be found in Sharp, H. (ed.). 1920. Selections from Educational Records, Part I (1781–1839). Superintendent, Govt. Printing, Calcutta) whilst disagreeing strongly with the proposed course of action agreed with this verdict: "It is laid down that the vernacular dialects are not fit to be made the vehicle of instruction in science or literature, that the choice is therefore between English on one hand and Sanskrit and Arabic on the other – the latter are dismissed on the ground that their literature is worthless and the superiority of that of England is set forth in all animated description of the treasures of science and of intelligence it contains and of the stores of intellectual enjoyment it opens. There is no body acquainted with both literatures that will not subscribe to all that is said in the minute of the superiority of that of England.

8. most likely because he had held them before the Minute was written; the Minute should therefore be read as a rumbustious justification of a foregone conclusion, not as an exercise in persuasive analysis. Perhaps the point was made to Macaulay at the time; in an essay published in the Edinburgh Review in July 1835 (and therefore roughly contemporaneous with the Minute), he wrote of Charles James Fox's History of James the Second: ..those more serious improprieties of manner into which a great orator who undertakes to write history is in danger of falling. There is about the whole book a vehement, contentious, replying manner. Almost every argument is put in the form of an interrogation, an ejaculation or a sarcasm. The writer seems to be addressing himself to some imaginary audience

"Sir James Mackintosh", Edinburgh Review, August 1825; included in T. B. Macaulay 'Critical and Historical Essays, Vol 1', J M Dent, London, 1910 [Everyman's Library, volume 225]

9. Prinsep, who was given a hard time on 2 different counts

• procedurally he should have waited to be asked before giving his views

• there was some suspicion that he had leaked news of the likely new policy to the Calcutta Madrassa students

10. Stephen Evans,"Macaulay’s Minute Revisited: Colonial Language Policy in Nineteenth-century India", Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development Vol. 23, No. 4, 2002

11. of whom Lord Melbourne is said to have remarked "I wish I was as cocksure of anything as Tom Macaulay is of everything" – see Oxford Dictionary of Quotations

12. 'Of the Government of Dependencies by a Free State' Chapter XVIII of 'Considerations on Representative Government' pages 382–384 of "Utilitarianism, Liberty & Representative Government", J S Mill, J M Dent & Sons Ltd, London (1910) [no 482 of 'Everyman's Library']

Further reading

• Caton, Alissa. "Indian in Colour, British in Taste: William Bentinck, Thomas Macaulay, and the Indian Education Debate, 1834-1835." Voces Novae 3.1 (2011): pp 39–60 online.

• Evans, Stephen. "Macaulay's minute revisited: Colonial language policy in nineteenth-century India." Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 23.4 (2002): 260–281.

• Ghosh, Suresh Chandra. "Bentinck, Macaulay and the introduction of English education in India." History of Education 24.1 (1995): 17–24.

• Kathiresan, B., and G. Sathurappasamy, "The People’s English." Asia Pacific Journal of Research 1#33 (2015) online.

• O'Dell, Benjamin D. "Beyond Bengal: Gender, Education, and the Writing of Colonial Indian History" Victorian Literature and Culture 42#3 (2014), pp. 535–551 online

• Spear, Percival. "Bentinck and Education" Cambridge Historical Journal 6#1 (1938), pp. 78–101 online

• Whitehead, Clive. "The historiography of British imperial education policy, Part I: India." History of Education 34.3 (2005): 315–329.

Primary sources

• Moir, Martin and Lynn Zastoupil, eds. The Great Indian Education Debate: Documents Relating to the Orientalist-Anglicist Controversy, 1781-1843 ( 1999 ) excerpts

• Elmer H. Cutts. “The Background of Macaulay’s Minute.” The American Historical Review 58, no. 4 (1953): 824–53. https://doi.org/10.2307/1842459.

• “The Letters of Thomas Babington Macaulay”, ed. by Thomas Pinney, vol. 3 (January 1834-August 1841). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976. https://franpritchett.com/00generallink ... sourceinfo.

• Sharp, Henry. “Selections from Educational Records (1840-59) Pt.2 : Richey, J. A. : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming.” Internet Archive, 1922. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dl ... Beducation.