Tipu Sultan [Tippoo Sultan]

by Wikipedia

Accessed 10/2/24

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tipu_Sultan

The earliest book printed in Bombay which is at present available is one published in 1793 under the following title: "Remarks and Occurrences of Mr. Henry Becher, during his imprisonment of two years and a half in the Dominions of Tippoo Sultan, from whence he made his escape." 5 [A copy of this book is available in the Heras Institute of Indian History and Culture, Bombay.] This book does not bear the name of the press where it was printed. It is clearly stated in the introduction of this book that "It is the first book ever printed in Bombay."1793 The Times 24 August

“We learn, that not withstanding Tippoo’s repeated declarations that he had no more English prisoners in his possession, it is evident that all those declarations have been insincere. Mr Becher, who some years ago was proceeding in a Pattamar boat, with stores for Mr. Rivitt’s ship at Cochin, was unfortunately driven on shore near Mangalore, and taken prisoner: after undergoing a long and painful imprisonment, and being marched from fort to fort, has at last effected his escape from Seringapatam. Latterly his confinement was not so strict as formerly, and he was sometimes permitted to go a shooting, under the guard of a sepoy, - One day having strolled a comfortable distance from the fort, he turned upon the sepoy & threatened to shoot him, if he did not accompany him – the sepoy was obliged to comply, and they are both now safely arrived at Tellicherry. Mr. Becher reports there are several prisoners at Seringapatram.”

-- https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~becher/ ... papers.htm

Tipu Sultan

Badshah

Nasib-ud-Daulah

Mir Fateh Ali Bahadur Tipu

Portrait of Tipu Sultan, from Mysore (c. 1790–1800).

Sultan of Mysore

Reign: 10 December 1782 – 4 May 1799

Coronation: 29 December 1782

Predecessor: Hyder Ali

Successor: Krishnaraja III (as Maharaja of Mysore)

Born: Sultan Fateh Ali Sahab Tipu, 1 December 1751, Devanahalli, Kingdom of Mysore (present-day Karnataka, India)

Died: 4 May 1799 (aged 47)

Burial: Srirangapatna, present-day Mandya, Karnataka

Spouse: Sultan Begum Sahib (m. 1774); Ruqaya Banu Begum (m. 1774); Khadija Zaman Begum (m. 1796; died 1797);

Buranti Begum; Roshani Begum

Issue: Shezada Hyder Ali, Ghulam Muhammad Sultan Sahib and many others

Names: Badshah Nasib-ud-Daulah Sultan Mir Fateh Ali Bahadur Saheb Tipu

House: Mysore

Father: Hyder Ali

Mother: Fatima Fakhr-un-Nisa

Religion: Sunni Islam[1][2][3][4]

Seal:

Military career

Service/branch: Mysore Army

Rank: Sultan

Battles/wars:

Second Anglo-Mysore War

Battle of Annagudi

Maratha-Mysore War

Battle of Moti Talab

Siege of Nargund

Siege of Adoni

Battle of Savanur

Siege of Bahadur Benda

Mysorean invasion of Malabar

Siege of Bednore

Battle of Nedumkotta

Third Anglo-Mysore War

Fourth Anglo-Mysore War

Siege of Seringapatam (1799) †

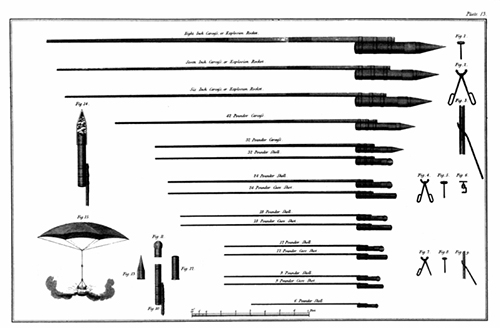

Tipu Sultan (Sultan Fateh Ali Sahab Tipu; 1 December 1751 – 4 May 1799), commonly referred to as Sher-e-Mysore or "Tiger of Mysore",[5][6] was an Indian ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore based in South India.[7] He was a pioneer of rocket artillery.[8][9][10] He expanded the iron-cased Mysorean rockets and commissioned the military manual Fathul Mujahidin. He deployed the rockets against advances of British forces and their allies during the Anglo-Mysore Wars, including the Battle of Pollilur and Siege of Srirangapatna.[11]

Tipu Sultan and his father Hyder Ali used their French-trained army in alliance with the French in their struggle with the British,[12] and in Mysore's struggles with other surrounding powers: against the Marathas, Sira, and rulers of Malabar, Kodagu, Bednore, Carnatic, and Travancore. Tipu became the ruler of Mysore upon his father's death from cancer in 1782 during the Second Anglo-Mysore War. He negotiated with the British in 1784 with the Treaty of Mangalore which ended the war in status quo ante bellum.

Tipu's conflicts with his neighbours included the Maratha–Mysore War, which ended with the signing of the Treaty of Gajendragad.[13]

Tipu remained an enemy of the British East India Company. He initiated an attack on British-allied Travancore in 1789. In the Third Anglo-Mysore War, he was forced into the Treaty of Seringapatam, losing a number of previously conquered territories, including Malabar and Mangalore. In the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War, a combined force of British East India Company troops supported by the Marathas and the Nizam of Hyderabad defeated Tipu. He was killed on 4 May 1799 while defending his stronghold of Seringapatam.

Tipu also introduced administrative innovations during his rule, including a new coinage system and calendar,[14] and a new land revenue system, which initiated the growth of the Mysore silk industry.[15] He is known for his patronage to Channapatna toys.[16]

Early years

Tipu's birthplace, Devanahalli.

Childhood

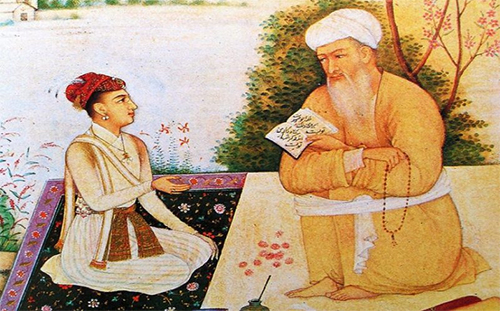

Tipu Sultan was born in Devanahalli, in present-day Bangalore Rural district, about 33 km (21 mi) north of Bangalore on 1 December 1751.[17][18] He was named "Tipu Sultan" after the saint Tipu Mastan Aulia of Arcot. Being illiterate, Hyder was very particular in giving his eldest son a prince's education and a very early exposure to military and political affairs. At age of 17 onwards Tipu was given charge of diplomatic and military missions and supported his father Hyder in his wars.[19]

Tipu's father, Hyder Ali, was a military officer in service to the Kingdom of Mysore who had become the de facto ruler of Mysore in 1761 while his mother Fatima Fakhr-un-Nisa was the daughter of Mir Muin-ud-Din, the governor of the fort of Kadapa. Hyder Ali appointed able teachers to give Tipu an early education in subjects like Urdu, Persian, Arabic, Kannada, beary, Quran, Islamic jurisprudence, riding, shooting and fencing.[17][20][21][22]

Language

Tipu Sultan's mother tongue was Urdu. The French noted that "Their language is Moorish[Urdu] but they also speak Persian."[23] Moors at the time was a European designation for Urdu: "I have a deep knowledge [je possède à fond] of the common tongue of India, called Moors by the English, and Ourdouzebain by the natives of the land."[24]

Early military service

War coat used by Tipu Sultan of Mysore.c. 1785-1790

A flintlock blunderbuss, built for Tipu Sultan in Srirangapatna, 1793–94. Tipu Sultan used many Western craftsmen, and this gun reflects the most up-to-date technologies of the time.[25]

Early Conflicts

Tipu Sultan was instructed in military tactics by French officers in the employment of his father. At age 15, he accompanied his father against the British in the First Mysore War in 1766. He commanded a corps of cavalry in the invasion of Carnatic in 1767 at age 16. He also took part in the First Anglo-Maratha War of 1775–1779.[26]

Alexander Beatson, who published a volume on the Fourth Mysore War entitled View of the Origin and Conduct of the War with Tippoo Sultaun, described Tipu Sultan as follows: "His stature was about five feet eight inches; he had a short neck, square shoulders, and was rather corpulent: his limbs were small, particularly his feet and hands; he had large full eyes, small arched eyebrows, and an aquiline nose; his complexion was fair, and the general expression of his countenance, not void of dignity".[27]

Second Anglo-Mysore War

Main articles: Second Anglo-Mysore War and Battle of Annagudi

Mural of the Battle of Pollilur on the walls of Tipu's summer palace, painted to celebrate his triumph over the British

Very small Cannon used by Tipu Sultan's forces now in Government Museum (Egmore), Chennai

In 1779, the British captured the French-controlled port of Mahé which Tipu had placed under his protection, providing some troops for its defence. In response, Hyder launched an invasion of the Carnatic, with the aim of driving the British out of Madras.[28] During this campaign in September 1780, Tipu Sultan was dispatched by Hyder Ali with 10,000 men and 18 guns to intercept Colonel William Baillie who was on his way to join Sir Hector Munro. In the Battle of Pollilur, Tipu defeated Baillie. Out of 360 Europeans, about 200 were captured alive, and the sepoys, who were about 3800 men, suffered very high casualties. Munro was moving south with a separate force to join Baillie, but on hearing the news of the defeat he retreated to Madras, abandoning his artillery in a water tank at Kanchipuram.[29]

Tipu Sultan defeated Colonel Braithwaite at Annagudi near Tanjore on 18 February 1782. Braithwaite's forces, consisting of 100 Europeans, 300 cavalry, 1400 sepoys and 10 field pieces, was the standard size of the colonial armies. Tipu Sultan seized all guns and took the detachment prisoner. In December 1781 Tipu Sultan seized Chittur from the British. Tipu Sultan had gained sufficient military experience by the time Hyder Ali died on Friday, 6 December 1782. Some historians put Hyder Ali's death at 2 or 3 days later or before due to the Hijri date being 1 Muharram, 1197 as per some records in Persian (which can result in a difference of 1 to 3 days due to the Lunar Calendar). He became the ruler of Mysore on Sunday, 22 December 1782 (the inscriptions in some of Tipu's regalia show it as 20 Muharram, 1197 Hijri Sunday) in a simple coronation ceremony. He subsequently worked on to check the advances of the British by making alliances with the Marathas and the Mughals. The Second Mysore War came to an end with the 1784 Treaty of Mangalore.[clarification needed][30]

Ruler of Mysore

On 29 December 1782, Tipu Sultan crowned himself Badshah or Emperor of Mysore with the title Nawab Tipu Sultan Bahadur at age 32, and struck coinage.[31]

Conflicts with Maratha Confederacy

See also: Battles involving the Maratha Empire § Conflict with the Kingdom of Mysore

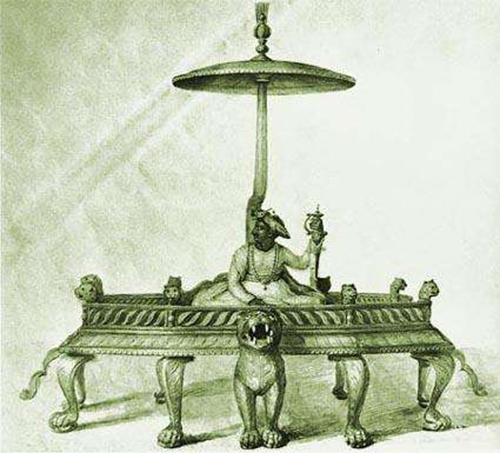

Tipu Sultan seated on his throne (1800), by Anna Tonelli

Tipu Sultan's Summer Palace at Srirangapatna, Karnataka

The Maratha Empire under its new Peshwa Madhavrao I regained most of Indian subcontinent, twice defeating Tipu's father in 1764 and then in 1767. In 1767 Maratha Peshwa Madhavrao defeated both Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan and entered Srirangapatna, the capital of Mysore. Hyder Ali accepted the authority of Madhavrao who gave him the title of Nawab of Mysore.[32]

Subsequently, to escape the treaty, Tipu tried to take some Maratha forts in Southern India captured by in the previous war and also stopped the tribute to Marathas which was promised by Hyder Ali.[33] This brought Tipu in direct conflict with the Marathas, leading to Maratha–Mysore War[33] Conflicts between Mysore (under Tipu) and Marathas:

• Siege of Nargund during February 1785 won by Mysore

• Siege of Badami during May 1786 in which Mysore surrendered

• Siege of Adoni during June 1786 won by Mysore

• Battle of Gajendragad, June 1786 won by Marathas

• Battle of Savanur during October 1786 won by Mysore

• Siege of Bahadur Benda during January 1787 won by Mysore

Conflict ended with Treaty of Gajendragad in March 1787, as per which Tipu returned all the territory captured by Hyder Ali to Maratha Empire.[33][34] Tipu would elease Kalopant and return Adoni, Kittur, and Nargund to their previous rulers. Badami would be ceded to the Marathas and Tipu would also pay an annual tribute totaling 12 lakhs for an agreed period of 4 years to the Marathas. In return, Tipu Sultan would get all the region that he had captured during the war. This included Gajendragarh and Dharwar.[35][36] The Marathas in return agreed to recognize his authority and to address Tipu sultan as "Nabob Tipu Sultan Futteh Ally Khan".[36] However the Marathas ultimately reneged on the treaty and in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War the Marathas presented their support to the British East India Company which helped the British to take over Mysore in 1799.[37][page needed][38]

The Invasion of Malabar (1766–1790)

Main article: Mysorean invasion of Malabar

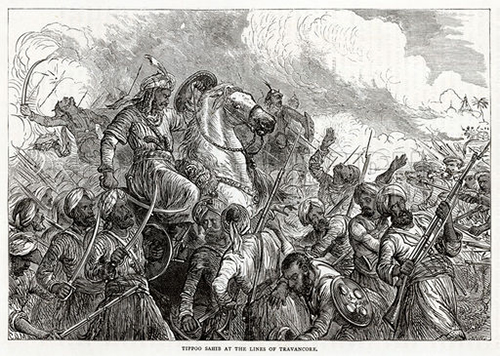

Tipu Sultan at the lines of Travancore.

In 1766 when he was 15 years old Tipu accompanied his father on an invasion of Malabar. After the incident- Siege of Tellicherry in Thalassery in North Malabar,[39] Hyder Ali started losing his territories in Malabar. Tipu came from Mysore to reinstate the authority over Malabar. After the Battle of the Nedumkotta (1789–90), due to the monsoon flood, the stiff resistance of the Travancore forces and news about the attack of British in Srirangapatnam he went back.[40]

Third Anglo-Mysore War

Main article: Third Anglo-Mysore War

Cannon used by Tipu Sultan's forces at the battle of Srirangapatna 1799

General Lord Cornwallis, receiving two of Tipu Sultan's sons as hostages in the year 1793.

In 1789, Tipu Sultan disputed the acquisition by Dharma Raja of Travancore of two Dutch-held fortresses in Cochin. In December 1789 he massed troops at Coimbatore, and on 28 December made an attack on the lines of Travancore, knowing that Travancore was (according to the Treaty of Mangalore) an ally of the British East India Company.[41] On account of the staunch resistance by the Travancore army, Tipu was unable to break through the Tranvancore lines and the Maharajah of Travancore appealed to the East India Company for help. In response, Lord Cornwallis mobilised company and British military forces, and formed alliances with the Marathas and the Nizam of Hyderabad to oppose Tipu. In 1790 the company forces advanced, taking control of much of the Coimbatore district.[41] Tipu counter-attacked, regaining much of the territory, although the British continued to hold Coimbatore itself. He then descended into the Carnatic, eventually reaching Pondicherry, where he attempted without success to draw the French into the conflict.[41]

In 1791 his opponents advanced on all fronts, with the main British force under Cornwallis taking Bangalore and threatening Srirangapatna. Tipu harassed the British supply and communication and embarked on a "scorched earth" policy of denying local resources to the British.[41] In this last effort he was successful, as the lack of provisions forced Cornwallis to withdraw to Bangalore rather than attempt a siege of Srirangapatna. Following the withdrawal, Tipu sent forces to Coimbatore, which they retook after a lengthy siege.[41]

The 1792 campaign was a failure for Tipu. The allied army was well-supplied, and Tipu was unable to prevent the junction of forces from Bangalore and Bombay before Srirangapatna.[41] After about two weeks of siege, Tipu opened negotiations for terms of surrender. In the ensuing treaty, he was forced to cede half his territories to the allies,[26] and deliver two of his sons as hostages until he paid in full three crores and thirty lakhs rupees fixed as war indemnity to the British for the campaign against him. He paid the amount in two instalments and got back his sons from Madras.[41]

Napoleon's attempt at a junction

Main article: Franco-Indian alliances

In 1794, with the support of French Republican officers, Tipu allegedly helped found the Jacobin Club of Mysore for 'framing laws comfortable with the laws of the Republic'. He planted a Liberty Tree and declared himself Citizen Tipoo.[42] In a 2005 paper, historian Jean Boutier argued that the club's existence, and Tipu's involvement in it, was fabricated by the East India Company in order to justify British military intervention against Tipu.[43]

One of the motivations of Napoleon's invasion of Egypt was to establish a junction with India against the British. Bonaparte wished to establish a French presence in the Middle East, with the ultimate dream of linking with Tippoo Sahib.[44] Napoleon assured the French Directory that "as soon as he had conquered Egypt, he will establish relations with the Indian princes and, together with them, attack the English in their possessions."[45] According to a 13 February 1798 report by Talleyrand: "Having occupied and fortified Egypt, we shall send a force of 15,000 men from Suez to India, to join the forces of Tipu-Sahib and drive away the English."[45] Napoleon was unsuccessful in this strategy, losing the Siege of Acre in 1799 and at the Battle of Abukir in 1801.[46]

Although I never supposed that he (Napoleon) possessed, allowing for some difference of education, the liberality of conduct and political views which were sometimes exhibited by old Hyder Ali, yet I did think he might have shown the same resolved and dogged spirit of resolution which induced Tipu Sahib to die manfully upon the breach of his capital city with his sabre clenched in his hand.

— Sir Walter Scott, commenting on the abdication of Napoleon Bonaparte in 1814

Death

Further information: Fourth Anglo-Mysore War

Tipu Sultan confronts his opponents during the Siege of Srirangapatna.

Horatio Nelson defeated François-Paul Brueys D'Aigalliers at the Battle of the Nile in Egypt in 1798. Three armies marched into Mysore in 1799—one from Bombay and two British, one of which included Arthur Wellesley.[47] They besieged the capital Srirangapatna in the Fourth Mysore War.[48] There were more than 60,000 soldiers of the British East India Company, approximately 4,000 Europeans and the rest Indians; while Tipu Sultan's forces numbered only around 30,000. The betrayal by Tipu Sultan's ministers in working with the British and weakening the walls to make an easy path for the British.[49][50] The death of Tipu Sultan led British General Harris to exclaim "Now India is ours."[37][page needed]

When the British broke through the city walls, French military advisers told Tipu Sultan[51] to escape via secret passages and to fight the rest of the wars from other forts, but he refused.[52] Tipu famously said "Better to live one day as a tiger than a thousand years as a sheep".[53]

The Last Effort and Fall of Tipu Sultan by Henry Singleton, c. 1800

Tipu Sultan was killed at the Hoally (Diddy) Gateway, which was located 300 yards (270 m) from the N.E. Angle of the Srirangapatna Fort.[54] He was buried the next afternoon at the Gumaz, next to the grave of his father. Many members of the British East India Company believed that Nawab of Carnatic Umdat Ul-Umra secretly provided assistance to Tipu Sultan during the war and sought his deposition after 1799.[citation needed] These five men include Mir Sadiq, Purnaiya, two military commanders Saiyed Saheb and Qamaruddin, and Mir Nadim, commandant of the fort of Seringapatam. The episode of treachery as narrated by Hasan starts with the disobedience of Tipu's instructions.[55] When he died there were jubilant celebrations in Britain, with authors, playwrights and painters creating works to celebrate it.[56] The death of Tipu Sultan was celebrated with declaration of public holiday in Britain.[57]

Administration

Tipu introduced a new calendar, new coinage, and seven new government departments, during his reign, and made military innovations in the use of rocketry.

Mysorean rockets

Main article: Mysorean rockets

A soldier from Tipu Sultan's army, using his rocket as a flagstaff.

Tipu Sultan organised his Rocket artillery brigades known as Cushoons, Tipu Sultan expanded the number of servicemen in the various Cushoons from 1500 to almost 5000. The Mysorean rockets utilised by Tipu Sultan, were later updated by the British and successively employed during the Napoleonic Wars.

Dr APJ Abdul Kalam, the former President of India, in his Tipu Sultan Shaheed Memorial Lecture in Bangalore (30 November 1991), called Tipu Sultan the innovator of the world's first war rocket. Two of these rockets, captured by the British at Srirangapatna, were displayed in the Royal Artillery Museum in London. According to historian Dr Dulari Qureshi Tipu Sultan was a fierce warrior king and was so quick in his movement that it seemed to the enemy that he was fighting on many fronts at the same time.[49] Tipu managed to subdue all the petty kingdoms in the south. He was also one of the few Indian rulers to have defeated British armies.

Tipu Sultan's father had expanded on Mysore's use of rocketry, making critical innovations in the rockets themselves and the military logistics of their use. He deployed as many as 1,200 specialised troops in his army to operate rocket launchers. These men were skilled in operating the weapons and were trained to launch their rockets at an angle calculated from the diameter of the cylinder and the distance to the target. The rockets had twin side sharpened blades mounted on them, and when fired en masse, spun and wreaked significant damage against a large army. Tipu greatly expanded the use of rockets after Hyder's death, deploying as many as 5,000 rocketeers at a time.[58] The rockets deployed by Tipu during the Battle of Pollilur were much more advanced than those the British East India Company had previously seen, chiefly because of the use of iron tubes for holding the propellant; this enabled higher thrust and longer range for the missiles (up to 2 km range).[58][11]

British accounts describe the use of the rockets during the third and fourth wars.[59] During the climactic battle at Srirangapatna in 1799, British shells struck a magazine containing rockets, causing it to explode and send a towering cloud of black smoke with cascades of exploding white light rising up from the battlements. After Tipu's defeat in the fourth war the British captured a number of the Mysorean rockets. These became influential in British rocket development, inspiring the Congreve rocket, which was soon put into use in the Napoleonic Wars.[11]

Navy

In 1786 Tipu Sultan, again following the lead of his father, decided to build a navy consisting of 20 battleships of 72 cannons and 20 frigates of 65 cannons. In the year 1790 he appointed Kamaluddin as his Mir Bahar and established massive dockyards at Jamalabad and Majidabad. Tipu Sultan's board of admiralty consisted of 11 commanders in service of a Mir Yam. A Mir Yam led 30 admirals and each one of them had two ships. Tipu Sultan ordered that the ships have copper-bottoms, an idea that increased the longevity of the ships and was introduced to Tipu by Admiral Suffren.[60]

Army

Due to their perpetual battle engagements, Haidar and Tipu required a disciplined standing army. Thus, Rajputs, Muslims and able tribal men were enrolled for full time service replacing the local militia called the Kandachar[61] force of agricultural origin which existed in the Mysore army earlier. The removal of the Vokkaligas from the local militia which had taken part in wars for centuries and the imposition of higher taxes on them in place of their quit rent led indirectly to the implementation of Ryotwari system. Now the Ryots could not rely upon slaves for their agricultural activities since their slaves were enrolled in the army in some places. Besides paying higher taxes they had to endure the additional responsibility of feeding the slaves and financing their marriages. This led to the weakening of the system of slavery in Mysore.[62]

Economy

Main article: Economy of the Kingdom of Mysore

Further information: Mysore silk and Economic history of India

The peak of Mysore's economic power was under Tipu Sultan in the late 18th century. Along with his father Hyder Ali, he embarked on an ambitious program of economic development, aiming to increase the wealth and revenue of Mysore.[63] Under his reign, Mysore overtook Bengal Subah as India's dominant economic power, with highly productive agriculture and textile manufacturing.[64] Mysore's average income was five times higher than subsistence level at the time.[65]

Tipu Sultan laid the foundation for the construction of the Kannambadi dam (present-day Krishna Raja Sagara or KRS dam) on the Kaveri river, as attested by an extant stone plaque bearing his name, but was unable to begin the construction.[66][67] The dam was later built and opened in 1938. It is a major source of drinking water for the people of Mysore and Bangalore.

The Mysore silk industry was first initiated during the reign of Tipu Sultan.[68] He sent an expert to Bengal Subah to study silk cultivation and processing, after which Mysore began developing polyvoltine silk.[15]

The greater prominence of the Channapatna toys can be traced to patronage from Tipu Sultan, the historic ruler of Mysore, though these toys existed before this period historically given as gifts as part of Dusshera celebrations. It is known that he was an ardent admirer of arts, and in particular of woodwork.[69][16]

Road development

Tipu Sultan was considered as pioneer of road construction, especially in Malabar, as part of his campaigns, he connected most of the cities by roads.[70]

Foreign relations

Louis XVI receives the ambassadors of Tipu Sultan in 1788. Tipu Sultan is known to have sent many diplomatic missions to France, the Ottoman Empire, Sultanate of Oman, Zand dynasty and Durrani Empire.[71]

Mughal Empire

Both Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan owed nominal allegiance to the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II; both were described as Nabobs by the British East India Company in all existing treaties. But unlike the Nawab of Carnatic, they did not acknowledge the overlordship of the Nizam of Hyderabad.[72]

Immediately after his coronation as Badshah, Tipu Sultan sought the investiture of the Mughal emperor. He earned the title "Nasib-ud-Daula" with the heavy heart of those loyal to Shah Alam II. Tipu was a selfdeclared "Sultan" this fact drew towards him the hostility of Nizam Ali Khan, the Nizam of Hyderabad, who clearly expressed his hostility by dissuading the Mughal emperor and laying claims on Mysore. Disheartened, Tipu Sultan began to establish contacts with other Muslim rulers of that period.[73]

Tipu Sultan was the master of his own diplomacy with foreign nations, in his quest to rid India of the East India Company and to ensure the international strength of France. Like his father before him he fought battles on behalf of foreign nations which were not in the best interests of Shah Alam II.

After Ghulam Qadir had Shah Alam II blinded on 10 August 1788, Tipu Sultan is believed to have broken into tears.[74][page needed]

Tipu Sultan's forces during the Siege of Srirangapatna.

After the Fall of Seringapatam in 1799, the blind emperor did remorse for Tipu, but maintained his confidence in the Nizam of Hyderabad, who had now made peace with the British.

Afghanistan

After facing substantial threats from the Marathas, Tipu Sultan began to correspond with Zaman Shah Durrani, the ruler of the Afghan Durrani Empire, so they could defeat the British and Marathas. Initially, Zaman Shah agreed to help Tipu, but the Persian attack on Afghanistan's Western border diverted its forces, and hence no help could be provided to Tipu.

Ottoman Empire

In 1787, Tipu Sultan sent an embassy to the Ottoman capital Constantinople, to the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid I requesting urgent assistance against the British East India Company. Tipu Sultan requested the Ottoman Sultan to send him troops and military experts. Furthermore, Tipu Sultan also requested permission from the Ottomans to contribute to the maintenance of the Islamic shrines in Mecca, Medina, Najaf and Karbala.

However, the Ottomans were themselves in crisis and still recuperating from the devastating Austro-Ottoman War and a new conflict with the Russian Empire had begun, for which Ottoman Turkey needed British alliance to keep off the Russians, hence it could not risk being hostile to the British in the Indian theatre.

Due to the Ottoman inability to organise a fleet in the Indian Ocean, Tipu Sultan's ambassadors returned home only with gifts from their Ottoman brothers.

Nevertheless, Tipu Sultan's correspondence with the Ottoman Empire and particularly its new Sultan Selim III continued till his final battle in the year 1799.[73]

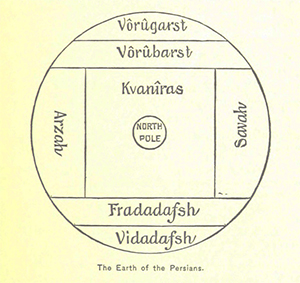

Persia and Oman

Like his father before him, Tipu Sultan maintained friendly relations with Mohammad Ali Khan, ruler of the Zand dynasty in Persia. Tipu Sultan also maintained correspondence with Hamad bin Said, the ruler of the Sultanate of Oman.[75]

Qing China

Tipu's and Mysore's tryst with silk began in the early 1780s when he received an ambassador from the Qing dynasty-ruled China at his court. The ambassador presented him with a silk cloth. Tipu was said to be enchanted by the item to such an extent that he resolved to introduce its production in his kingdom. He sent a return journey to China, which returned after twelve years.[76]

France

In his attempts to junction with Tipu Sultan, Napoleon annexed Ottoman Egypt in the year 1798.

Both Hyder Ali and Tipu sought an alliance with the French, the only European power still strong enough to challenge the British East India Company in the subcontinent. In 1782, Louis XVI concluded an alliance with the Peshwa Madhu Rao Narayan. This treaty enabled Bussy to move his troops to the Isle de France (now Mauritius). In the same year, French Admiral De Suffren ceremonially presented a portrait of Louis XVI to Haidar Ali and sought his alliance.[77]

Napoleon conquered Egypt in an attempt to link with Tipu Sultan.[citation needed] In February 1798, Napoleon wrote a letter to Tipu Sultan appreciating his efforts of resisting the British annexation and plans, but this letter never reached Tipu and was seized by a British spy in Muscat. The idea of a possible Tipu-Napoleon alliance alarmed the British Governor, General Sir Richard Wellesley (also known as Lord Wellesley), so much that he immediately started large scale preparations for a final battle against Tipu Sultan.

Social system

Judicial system

Tipu Sultan appointed judges from both communities for Hindu and Muslim subjects. Qadi for Muslims and Pandit for Hindus in each province. Upper courts also had similar systems.[78]

Moral Administration

Usage of liquor and prostitution were strictly prohibited in his administration.[79] Usage and agriculture of psychedelics, such as Cannabis, was also prohibited.[80]

Polyandry in Kerala was prohibited by Tipu Sultan. He passed a decree for all women to cover their breasts, which was not practised in Kerala in the previous era.[81][82]

Religious policy

On a personal level, Tipu was a devout Muslim, saying his prayers daily and paying special attention to mosques in the area.[83] Regular endowments were made during this period to about 156 Hindu temples,[84] including the famed Ranganathaswami Temple at Srirangapatna.[85] Many sources mention the appointment of Hindu officers in Tipu's administration[86] and his land grants and endowments to Hindu temples,[87][88][89] which are cited as evidence for his religious tolerance.

His religious legacy has become a source of considerable controversy in India, with some groups (including Christians[90] and even Muslims) proclaiming him a great warrior for the faith or Ghazi[91][92] for both religious and political reasons.[85] Various sources describe the massacres,[93] imprisonment[94] and forced conversion[95] of Hindus (Kodavas of Coorg, Nairs of Malabar) and Christians (Catholics of Mangalore), the destruction of churches[96] and temples, and the clamping down on Muslims (Mappila of Kerala, the Mahdavia Muslims, the rulers of Savanur and the people of Hyderabad State), which are sometimes cited as evidence for his intolerance.

British accounts

Historians such as Brittlebank, Hasan, Chetty, Habib, and Saletare, amongst others, argue that controversial stories of Tipu Sultan's religious persecution of Hindus and Christians are largely derived from the work of early British authors (who were very much against Tipu Sultan's independence and harboured prejudice against the Sultan) such as James Kirkpatrick[97] and Mark Wilks,[98] whom they do not consider to be entirely reliable and likely fabricated.[99] A. S. Chetty argues that Wilks' account in particular cannot be trusted.[100]

Irfan Habib and Mohibbul Hasan argue that these early British authors had a strong vested interest in presenting Tipu Sultan as a tyrant from whom the British had liberated Mysore.[99][101] This assessment is echoed by Brittlebank in her recent work where she writes that Wilks and Kirkpatrick must be used with particular care as both authors had taken part in the wars against Tipu Sultan and were closely connected to the administrations of Lord Cornwallis and Richard Wellesley, 1st Marquess Wellesley.[102]

Relations with Hindus

Tipu Sultan's treasurer was Krishna Rao, Shamaiya Iyengar was his Minister of Post and Police, his brother Ranga Iyengar was also an officer, and Purnaiya held the very important post of "Mir Asaf". Moolchand and Sujan Rai were his chief agents at the Mughal court, and his chief "Peshkar", Suba Rao, was also a Hindu.[86]

The Editor of Mysore Gazette reports of correspondence between his court and temples, and his having donated jewellery and deeded land grants to several temples, which he was compelled to for forming alliances with Hindu rulers. Between 1782 and 1799 Tipu Sultan issued 34 "Sanads" (deeds) of endowment to temples in his domain, while also presenting many of them with gifts of silver and gold plate.[89]

The Srikanteswara Temple in Nanjangud still possesses a jeweled cup presented by the Sultan.[88] He also gave a greenish linga; to Ranganatha temple at Srirangapatna, he donated seven silver cups and a silver camphor burner. This temple was hardly a stone's throw from his palace from where he would listen with equal respect to the ringing of temple bells and the muezzin's call from the mosque; to the Lakshmikanta Temple at Kalale he gifted four cups, a plate and Spitoon in silver.[87][89]

During the Maratha–Mysore War in 1791, a group of Maratha horsemen under Raghunath Rao Patwardhan raided the temple and matha of Sringeri Shankaracharya. They wounded and killed many people, including Brahmins, plundered the monastery of all its valuable possessions, and desecrated the temple by displacing the image of goddess Sarada.[86]

The incumbent Shankaracharya petitioned Tipu Sultan for help. About 30 letters written in Kannada, which were exchanged between Tipu Sultan's court and the Sringeri Shankaracharya, were discovered in 1916 by the Director of Archaeology in Mysore. Tipu Sultan expressed his indignation and grief at the news of the raid:[86][103]

"People who have sinned against such a holy place are sure to suffer the consequences of their misdeeds at no distant date in this Kali age in accordance with the verse: "Hasadbhih kriyate karma rudadbhir-anubhuyate" (People do [evil] deeds smilingly but suffer the consequences crying)."[104]

He immediately ordered the Asaf of Bednur to supply the Swami with 200 rahatis (fanams) in cash and other gifts and articles. Tipu Sultan's interest in the Sringeri temple continued for many years, and he was still writing to the Swami in the 1790s.[105]

In light of this and other events, historian B. A. Saletare has described Tipu Sultan as a defender of the Hindu dharma, who also patronised other temples including one at Melkote, for which he issued a Kannada decree that the Shrivaishnava invocatory verses there should be recited in the traditional form.[106] The temple at Melkote still has gold and silver vessels with inscriptions indicating that they were presented by the Sultan. Tipu Sultan also presented four silver cups to the Lakshmikanta Temple at Kalale.[106] Tipu Sultan does seem to have repossessed unauthorised grants of land made to Brahmins and temples, but those which had proper sanads (certificates) were not. It was a normal practice for any ruler, Muslim or Hindu, on his accession or on the conquest of new territory.

Persecution of Kodavas outside Mysore

Main article: Captivity of Kodavas at Seringapatam

Tipu got Runmust Khan, the Nawab of Kurnool, to launch a surprise attack upon the Kodavas who were besieged by the invading Muslim army. 500 were killed and over 40,000 Kodavas fled to the woods and concealed themselves in the mountains.[107] Thousands of Kodavas were seized along with the Raja and held captive at Seringapatam.[95]

Mohibbul Hasan, Prof. Sheikh Ali, and other historians cast great doubt on the scale of the deportations and forced conversions in Coorg in particular. Hassan says that it is difficult to estimate the real number of Kodava captured by Tipu.[108]

In a letter to Runmust Khan, Tipu himself stated:[109]

"We proceeded with the utmost speed, and, at once, made prisoners of 40,000 occasion-seeking and sedition-exciting Kodavas, who alarmed at the approach of our victorious army, had slunk into woods, and concealed themselves in lofty mountains, inaccessible even to birds. Then carrying them away from their native country (the native place of sedition) we raised them to the honour of Islam, and incorporated them into our Ahmedy corps." [110]