Darius the Greatby Wikipedia

Accessed: 11/17/24

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Darius_the_GreatDarius the Great

The relief stone of Darius the Great in the Behistun Inscription

The relief stone of Darius the Great in the Behistun InscriptionKing of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire

Reign: 29 September 522 BCE – October 486 BCE

Coronation: Pasargadae

Predecessor: Bardiya

Successor: Xerxes I

Born: c. 550 BCE

Died: October 486 BCE

Burial: Naqsh-e Rostam

Spouse: Atossa Artystone Parmys Phratagune Phaedymiaa, daughter of Gobryas

Issue: Artobazanes Xerxes I; Ariabignes Arsamenes; Masistes Achaemenes; Arsames Gobryas; Ariomardus Abrocomes; Hyperanthes Artazostre

Names: Dārayava(h)uš

Dynasty: Achaemenid

Father: Hystaspes

Mother: Rhodogune or Irdabama

Religion: Indo-Iranian religion

Darius I (Old Persian: [x] Dārayavaʰuš; c. 550 – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his death in 486 BCE. He ruled the empire at its territorial peak, when it included much of Western Asia, parts of the Balkans (Thrace–Macedonia and Paeonia) and the Caucasus, most of the Black Sea's coastal regions, Central Asia, the Indus Valley in the far east, and portions of North Africa and Northeast Africa including Egypt (Mudrâya), eastern Libya, and coastal Sudan.[1][2]

Darius ascended the throne by overthrowing the Achaemenid monarch Bardiya (or Smerdis), who he claimed was in fact an imposter named Gaumata. The new king met with rebellions throughout the empire but quelled each of them; a major event in Darius's life was his expedition to subjugate Greece and punish Athens and Eretria for their participation in the Ionian Revolt. Although his campaign ultimately resulted in failure at the Battle of Marathon, he succeeded in the re-subjugation of Thrace and expanded the Achaemenid Empire through his conquests of Macedonia, the Cyclades, and the island of Naxos.

Darius organized the empire by dividing it into administrative provinces, each governed by a satrap. He organized Achaemenid coinage as a new uniform monetary system, and he made Aramaic a co-official language of the empire alongside Persian. He also put the empire in better standing by building roads and introducing standard weights and measures. Through these changes, the Achaemenid Empire became centralized and unified.[3] Darius undertook other construction projects throughout his realm, primarily focusing on Susa, Pasargadae, Persepolis, Babylon, and Egypt. He had an inscription carved upon a cliff-face of Mount Behistun to record his conquests, which would later become important evidence of the Old Persian language.

EtymologyMain article: Darius (given name)

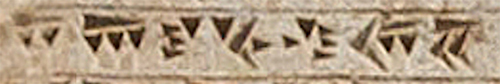

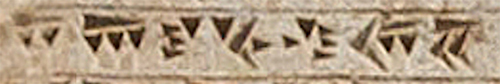

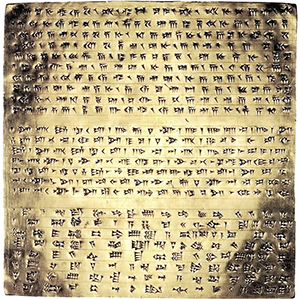

The name of Darius I in Old Persian cuneiform on the DNa inscription of his tomb: Dārayavauš ([x])

The name of Darius I in Old Persian cuneiform on the DNa inscription of his tomb: Dārayavauš ([x])Dārīus and Dārēus are the Latin forms of the Greek Dareîos (Δαρεῖος), itself from Old Persian Dārayauš ([x], d-a-r-y-uš; which is a shortened form of Dārayavaʰuš ([x], d-a-r-y-v-u-š). The longer Persian form is reflected in the Elamite Da-ri-(y)a-ma-u-iš, Babylonian Da-(a-)ri-ia-(a-)muš, and Aramaic drywhwš ([x]) forms, and possibly in the longer Greek form, Dareiaîos ([x]). The name in nominative form means "he who holds firm the good(ness)", which can be seen by the first part dāraya, meaning "holder", and the adverb vau, meaning "goodness".[4]

Primary sourcesSee also: Behistun Inscription, DNa inscription, and Herodotus

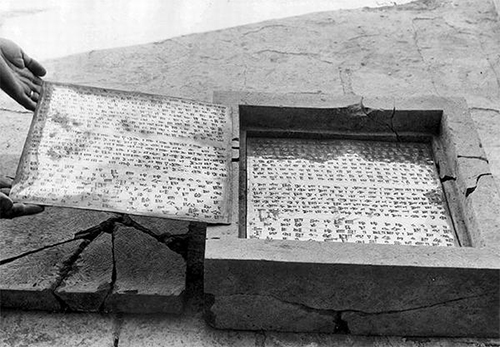

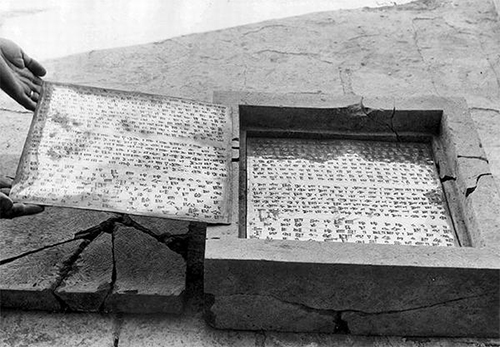

Apadana foundation tablets of Darius the Great

Gold foundation tablets of Darius I for the Apadana Palace, in their original stone box. The Apadana coin hoard had been deposited underneath (c. 510 BCE).

Gold foundation tablets of Darius I for the Apadana Palace, in their original stone box. The Apadana coin hoard had been deposited underneath (c. 510 BCE).

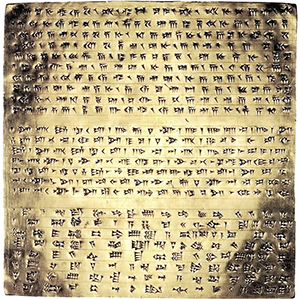

One of the two gold deposition plates. Two more were in silver. They all had the same trilingual inscription (DPh inscription).

At some time between his coronation and his death, Darius left a tri-lingual monumental relief on Mount Behistun, which was written in Elamite, Old Persian and Babylonian. The inscription begins with a brief autobiography including his ancestry and lineage. To aid the presentation of his ancestry, Darius wrote down the sequence of events that occurred after the death of Cyrus the Great.[5][6] Darius mentions several times that he is the rightful king by the grace of the supreme deity Ahura Mazda. In addition, further texts and monuments from Persepolis have been found, as well as a clay tablet containing an Old Persian cuneiform of Darius from Gherla, Romania (Harmatta) and a letter from Darius to Gadates, preserved in a Greek text of the Roman period.[7][8][9][10] In the foundation tablets of Apadana Palace, Darius described in Old Persian cuneiform the extent of his Empire in broad geographical terms:[11][12]

Darius the great king, king of kings, king of countries, son of Hystaspes, an Achaemenid. King Darius says: This is the kingdom which I hold, from the Sacae who are beyond Sogdia to Kush, and from Sind (Old Persian: [x], "Hidauv", locative of "Hiduš", i.e. "Indus valley") to Lydia (Old Persian: "Spardâ") – [this is] what Ahuramazda, the greatest of gods, bestowed upon me. May Ahuramazda protect me and my royal house!

— DPh inscription of Darius I in the foundations of the Apadana Palace

Herodotus, a Greek historian and author of The Histories, provided an account of many Persian kings and the Greco-Persian Wars. He wrote extensively on Darius, spanning half of Book 3 along with Books 4, 5 and 6. It begins with the removal of the alleged usurper Gaumata and continues to the end of Darius's reign.[7]

Early lifeThe predecessor of Darius: Bardiya/ Gaumata "Gaumata" being trampled upon by Darius the Great, Behistun inscription. The Old Persian inscription reads "This is Gaumâta, the Magian. He lied, saying "I am Smerdis, the son of Cyrus, I am king"."[13]

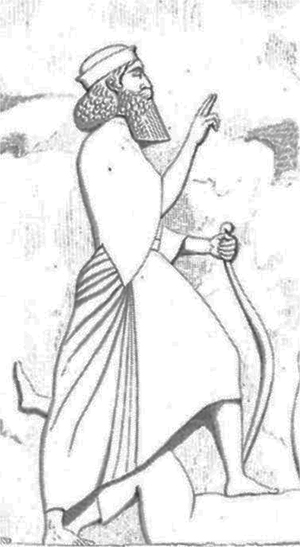

"Gaumata" being trampled upon by Darius the Great, Behistun inscription. The Old Persian inscription reads "This is Gaumâta, the Magian. He lied, saying "I am Smerdis, the son of Cyrus, I am king"."[13] Portrait of Achaemenid King Bardiya, or "Gaumata", from the reliefs at Behistun (detail).

Portrait of Achaemenid King Bardiya, or "Gaumata", from the reliefs at Behistun (detail).Darius toppled the previous Achaemenid ruler (here depicted in the reliefs of the Behistun inscription) to acquire the throne.

Darius was the eldest of five sons to Hystaspes.[7] The identity of his mother is uncertain. According to the modern historian Alireza Shapour Shahbazi (1994), Darius's mother was thought to have been a woman named Rhodogune.[7] However, according to Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones (2013), recently uncovered texts in Persepolis indicate that his mother was Irdabama, an affluent landowner descended from a family of local Elamite rulers.[14] Richard Stoneman likewise refers to Irdabama as the mother of Darius.[15] The Behistun Inscription of Darius states that his father was satrap of Bactria in 522 BCE.[a] According to Herodotus (III.139), Darius, prior to seizing power and "of no consequence at the time", had served as a spearman (doryphoros) in the Egyptian campaign (528–525 BCE) of Cambyses II, then the Persian Great King;[18] this is often interpreted to mean he was the king's personal spear-carrier, an important role. Hystaspes was an officer in Cyrus's army and a noble of his court.[19]

Before Cyrus and his army crossed the river Araxes to battle with the Armenians, he installed his son Cambyses II as king in case he should not return from battle.[20] However, once Cyrus had crossed the Aras River, he had a vision in which Darius had wings atop his shoulders and stood upon the confines of Europe and Asia (the known world). When Cyrus awoke from the dream, he inferred it as a great danger to the future security of the empire, as it meant that Darius would one day rule the whole world. However, his son Cambyses was the heir to the throne, not Darius, causing Cyrus to wonder if Darius was forming treasonable and ambitious designs. This led Cyrus to order Hystaspes to go back to Persis and watch over his son strictly, until Cyrus himself returned.[21]

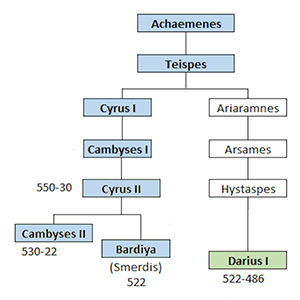

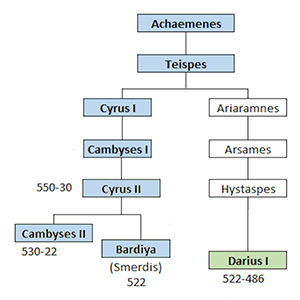

Accession Lineage of Darius the Great according to the Behistun Inscription.

Lineage of Darius the Great according to the Behistun Inscription.There are different accounts of the rise of Darius to the throne from both Darius himself and Greek historians. The oldest records report a convoluted sequence of events in which Cambyses II lost his mind, murdered his brother Bardiya, and was killed by an infected leg wound. After this, Darius and a group of six nobles traveled to Sikayauvati to kill an usurper, Gaumata, who had taken the throne by pretending to be Bardiya during the true king's absence.

Darius's account, written at the Behistun Inscription, states that Cambyses II killed his own brother Bardiya, but that this murder was not known among the Iranian people. A would-be usurper named Gaumata came and lied to the people, stating that he was Bardiya.[22] The Iranians had grown rebellious against Cambyses's rule and, on 11 March 522 BCE, a revolt against Cambyses broke out in his absence. On 1 July, the Iranian people chose to be under the leadership of Gaumata, as "Bardiya". No member of the Achaemenid family would rise against Gaumata for the safety of their own life. Darius, who had served Cambyses as his lance-bearer until the deposed ruler's death, prayed for aid and, in September 522 BCE, along with Otanes, Intaphrenes, Gobryas, Hydarnes, Megabyzus and Aspathines, killed Gaumata in the fortress of Sikayauvati.[22]

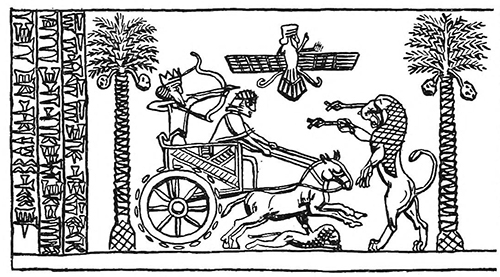

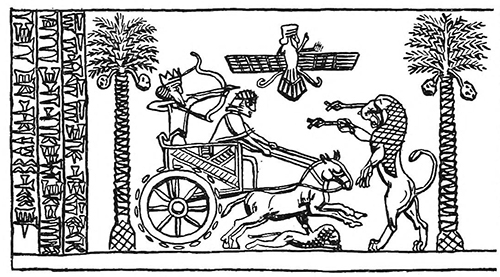

Cylinder seal of Darius the Great

Impression of a cylinder seal of King Darius the Great hunting in a chariot, reading "I am Darius, the Great King" in Old Persian ([x], "adam Dārayavaʰuš xšāyaθiya"), Elamite and Babylonian. The word 'great' only appears in Babylonian. British Museum, excavated in Thebes, Egypt.[23][24][25]

Impression of a cylinder seal of King Darius the Great hunting in a chariot, reading "I am Darius, the Great King" in Old Persian ([x], "adam Dārayavaʰuš xšāyaθiya"), Elamite and Babylonian. The word 'great' only appears in Babylonian. British Museum, excavated in Thebes, Egypt.[23][24][25]Herodotus provides a dubious account of Darius's ascension: Several days after Gaumata had been assassinated, Darius and the other six nobles discussed the fate of the empire. At first, the seven discussed the form of government: A democratic republic (Isonomia) was strongly pushed by Otanes, an oligarchy was pushed by Megabyzus, while Darius pushed for a monarchy. After stating that a republic would lead to corruption and internal fighting, while a monarchy would be led with a single-mindedness not possible in other governments, Darius was able to convince the other nobles.

To decide who would become the monarch, six of them decided on a test, with Otanes abstaining, as he had no interest in being king. They were to gather outside the palace, mounted on their horses at sunrise, and the man whose horse neighed first in recognition of the rising sun would become king. According to Herodotus, Darius had a slave, Oebares, who rubbed his hand over the genitals of a mare that Darius's horse favored. When the six gathered, Oebares placed his hands beside the nostrils of Darius's horse, who became excited at the scent and neighed. This was followed by lightning and thunder, leading the others to dismount and kneel before Darius in recognition of his apparent divine providence.[26] In this account, Darius himself claimed that he achieved the throne not through fraud, but cunning, even erecting a statue of himself mounted on his neighing horse with the inscription: "Darius, son of Hystaspes, obtained the sovereignty of Persia by the sagacity of his horse and the ingenious contrivance of Oebares, his groom."[27]

According to the accounts of Greek historians, Cambyses II had left Patizeithes in charge of the kingdom when he headed for Egypt. He later sent Prexaspes to murder Bardiya. After the killing, Patizeithes put his brother Gaumata, a Magian who resembled Bardiya, on the throne and declared him the Great King. Otanes discovered that Gaumata was an impostor, and along with six other Iranian nobles, including Darius, created a plan to oust the pseudo-Bardiya. After killing the impostor along with his brother Patizeithes and other Magians, Darius was crowned king the following morning.[7]

The details regarding Darius's rise to power is generally acknowledged as forgery and was in reality used as a concealment of his overthrow and murder of Cyrus's rightful successor, Bardiya.[28][29][30] To legitimize his rule, Darius had a common origin fabricated between himself and Cyrus by designating Achaemenes as the eponymous founder of their dynasty.[28] In reality, Darius was not from the same house as Cyrus and his forebears, the rulers of Anshan.[28][31]

Early reign

Early revolts Darius the Great, by Eugène Flandin (1840)

Darius the Great, by Eugène Flandin (1840)Main article: Achaemenid Civil War (522-520 BC)

Following his coronation at Pasargadae, Darius moved to Ecbatana. He soon learned that support for Bardiya was strong, and revolts in Elam and Babylonia had broken out.[32] Darius ended the Elamite revolt when the revolutionary leader Aschina was captured and executed in Susa. After three months the revolt in Babylonia had ended. While in Babylonia, Darius learned a revolution had broken out in Bactria, a satrapy which had always been in favour of Darius, and had initially volunteered an army of soldiers to quell revolts. Following this, revolts broke out in Persis, the homeland of the Persians and Darius and then in Elam and Babylonia, followed by in Media, Parthia, Assyria, and Egypt.[33]

By 522 BCE, there were revolts against Darius in most parts of the Achaemenid Empire leaving the empire in turmoil. Even though Darius did not seem to have the support of the populace, Darius had a loyal army, led by close confidants and nobles (including the six nobles who had helped him remove Gaumata). With their support, Darius was able to suppress and quell all revolts within a year. In Darius's words, he had killed a total of nine "lying kings" through the quelling of revolutions.[34] Darius left a detailed account of these revolutions in the Behistun Inscription.[34]

Elimination of IntaphernesOne of the significant events of Darius's early reign was the slaying of Intaphernes, one of the seven noblemen who had deposed the previous ruler and installed Darius as the new monarch.[35] The seven had made an agreement that they could all visit the new king whenever they pleased, except when he was with a woman.[35] One evening, Intaphernes went to the palace to meet Darius, but was stopped by two officers who stated that Darius was with a woman.[35] Becoming enraged and insulted, Intaphernes drew his sword and cut off the ears and noses of the two officers.[35] While leaving the palace, he took the bridle from his horse, and tied the two officers together.

The officers went to the king and showed him what Intaphernes had done to them. Darius began to fear for his own safety; he thought that all seven noblemen had banded together to rebel against him and that the attack against his officers was the first sign of revolt. He sent a messenger to each of the noblemen, asking them if they approved of Intaphernes's actions. They denied and disavowed any connection with Intaphernes's actions, stating that they stood by their decision to appoint Darius as King of Kings. Darius's choice to ask the noblemen indicates that he was not yet completely sure of his authority.[35]

Taking precautions against further resistance, Darius sent soldiers to seize Intaphernes, along with his son, family members, relatives and any friends who were capable of arming themselves. Darius believed that Intaphernes was planning a rebellion, but when he was brought to the court, there was no proof of any such plan. Nonetheless, Darius killed Intaphernes's entire family, excluding his wife's brother and son. She was asked to choose between her brother and son. She chose her brother to live. Her reasoning for doing so was that she could have another husband and another son, but she would always have but one brother. Darius was impressed by her response and spared both her brother's and her son's life.[36]

Military campaigns

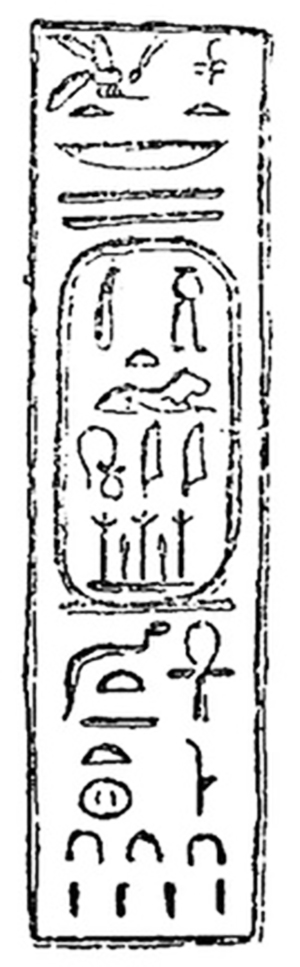

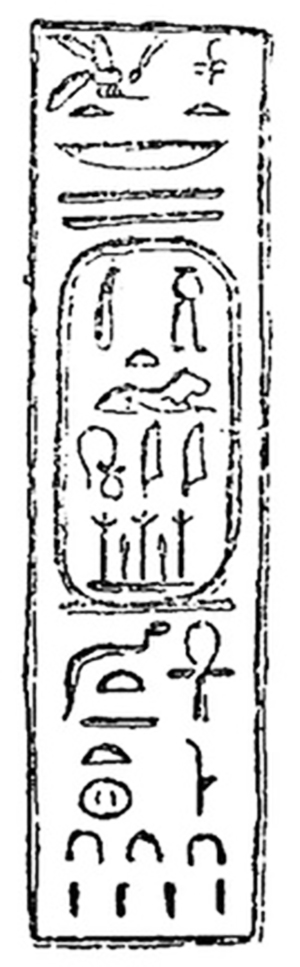

Egyptian alabaster vase of Darius I with quadrilingual hieroglyphic and cuneiform inscriptions. The hieroglyph on the vase reads: "King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Lord of the Two Lands, Darius, living forever, year 36".[37][38]Egyptian campaign

Egyptian alabaster vase of Darius I with quadrilingual hieroglyphic and cuneiform inscriptions. The hieroglyph on the vase reads: "King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Lord of the Two Lands, Darius, living forever, year 36".[37][38]Egyptian campaignMain article: Twenty-seventh Dynasty of Egypt

After securing his authority over the entire empire, Darius embarked on a campaign to Egypt where he defeated the armies of the Pharaoh and secured the lands that Cambyses had conquered while incorporating a large portion of Egypt into the Achaemenid Empire.[39]

Through another series of campaigns, Darius I would eventually reign over the territorial apex of the empire, when it stretched from parts of the Balkans (Thrace-Macedonia, Bulgaria-Paeonia) in the west, to the Indus Valley in the east.

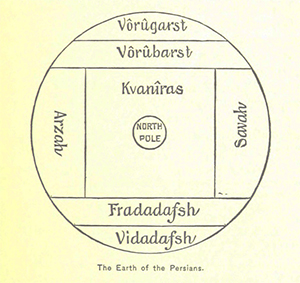

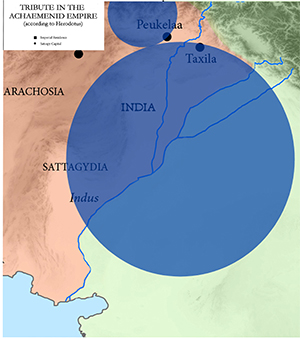

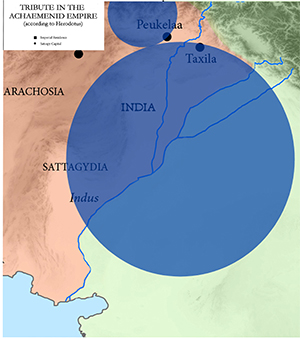

Invasion of the Indus Valley Eastern border of the Achaemenid Empire

Eastern border of the Achaemenid EmpireMain article: Achaemenid invasion of the Indus Valley

In 516 BCE, Darius embarked on a campaign to Central Asia, Aria and Bactria and then marched into Afghanistan to Taxila in modern-day Pakistan. Darius spent the winter of 516–515 BCE in Gandhara, preparing to conquer the Indus Valley. Darius conquered the lands surrounding the Indus River in 515 BCE. Darius I controlled the Indus Valley from Gandhara to modern Karachi and appointed the Greek Scylax of Caryanda to explore the Indian Ocean from the mouth of the Indus to Suez. Darius then marched through the Bolan Pass and returned through Arachosia and Drangiana back to Persia.

Babylonian revoltAfter Bardiya was murdered, widespread revolts occurred throughout the empire, especially on the eastern side. Darius asserted his position as king by force, taking his armies throughout the empire, suppressing each revolt individually. The most notable of all these revolts was the Babylonian revolt which was led by Nebuchadnezzar III. This revolt occurred when Otanes withdrew much of the army from Babylon to aid Darius in suppressing other revolts. Darius felt that the Babylonian people had taken advantage of him and deceived him, which resulted in Darius gathering a large army and marching to Babylon. At Babylon, Darius was met with closed gates and a series of defences to keep him and his armies out.[40]

Darius encountered mockery and taunting from the rebels, including the famous saying "Oh yes, you will capture our city, when mules shall have foals." For a year and a half, Darius and his armies were unable to retake the city, though he attempted many tricks and strategies—even copying that which Cyrus the Great had employed when he captured Babylon. However, the situation changed in Darius's favour when, according to the story, a mule owned by Zopyrus, a high-ranking soldier, foaled. Following this, a plan was hatched for Zopyrus to pretend to be a deserter, enter the Babylonian camp, and gain the trust of the Babylonians. The plan was successful and Darius's army eventually surrounded the city and overcame the rebels.[41]

During this revolt, Scythian nomads took advantage of the disorder and chaos and invaded Persia. Darius first finished defeating the rebels in Elam, Assyria, and Babylon and then attacked the Scythian invaders. He pursued the invaders, who led him to a marsh; there he found no known enemies but an enigmatic Scythian tribe.[42]

European Scythian campaignMain article: European Scythian campaign of Darius I

Map of the European Scythian campaign of Darius I

Map of the European Scythian campaign of Darius IThe Scythians were a group of north Iranian nomadic tribes, speaking an Eastern Iranian language (Scythian languages) who had invaded Media, killed Cyrus in battle, revolted against Darius and threatened to disrupt trade between Central Asia and the shores of the Black Sea as they lived between the Danube River, River Don and the Black Sea.[7][43]

Darius crossed the Black Sea at the Bosphorus Straits using a bridge of boats. Darius conquered large portions of Eastern Europe, even crossing the Danube to wage war on the Scythians. Darius invaded European Scythia in 513 BCE,[44] where the Scythians evaded Darius's army, using feints and retreating eastwards while laying waste to the countryside, by blocking wells, intercepting convoys, destroying pastures and continuous skirmishes against Darius's army.[45] Seeking to fight with the Scythians, Darius's army chased the Scythian army deep into Scythian lands, where there were no cities to conquer and no supplies to forage. In frustration Darius sent a letter to the Scythian ruler Idanthyrsus to fight or surrender. The ruler replied that he would not stand and fight with Darius until they found the graves of their fathers and tried to destroy them. Until then, they would continue their strategy as they had no cities or cultivated lands to lose.[46]

Despite the evading tactics of the Scythians, Darius's campaign was so far relatively successful.[47] As presented by Herodotus, the tactics used by the Scythians resulted in the loss of their best lands and of damage to their loyal allies.[47] This gave Darius the initiative.[47] As he moved eastwards in the cultivated lands of the Scythians in Eastern Europe proper, he remained resupplied by his fleet and lived to an extent off the land.[47] While moving eastwards in the European Scythian lands, he captured the large fortified city of the Budini, one of the allies of the Scythians, and burnt it.[47]

Darius eventually ordered a halt at the banks of Oarus, where he built "eight great forts, some eight miles [13 km] distant from each other", no doubt as a frontier defence.[47] In his Histories, Herodotus states that the ruins of the forts were still standing in his day.[48] After chasing the Scythians for a month, Darius's army was suffering losses due to fatigue, privation and sickness. Concerned about losing more of his troops, Darius halted the march at the banks of the Volga River and headed towards Thrace.[49] He had conquered enough Scythian territory to force the Scythians to respect the Persian forces.[7][50]

Persian invasion of GreeceMain article: First Persian invasion of Greece

See also: Ionian Revolt

Map showing key sites during the Persian invasions of Greece

Map showing key sites during the Persian invasions of GreeceDarius's European expedition was a major event in his reign, which began with the invasion of Thrace. Darius also conquered many cities of the northern Aegean, Paeonia, while Macedonia submitted voluntarily, after the demand of earth and water, becoming a vassal kingdom.[51] He then left Megabyzus to conquer Thrace, returning to Sardis to spend the winter. The Greeks living in Asia Minor and some of the Greek islands had submitted to Persian rule already by 510 BCE. Nonetheless, there were certain Greeks who were pro-Persian, although these were largely based in Athens. To improve Greek-Persian relations, Darius opened his court and treasuries to those Greeks who wanted to serve him. These Greeks served as soldiers, artisans, statesmen and mariners for Darius. However, the increasing concerns amongst the Greeks over the strength of Darius's kingdom along with the constant interference by the Greeks in Ionia and Lydia were stepping stones towards the conflict that was yet to come between Persia and certain of the leading Greek city states.

The "Darius Vase" at the Archaeological Museum of Naples. c. 340–320 BCE.

The "Darius Vase" at the Archaeological Museum of Naples. c. 340–320 BCE. Detail of Darius, with a label in Greek ([x], top right) giving his name.

Detail of Darius, with a label in Greek ([x], top right) giving his name.When Aristagoras organized the Ionian Revolt, Eretria and Athens supported him by sending ships and troops to Ionia and by burning Sardis. Persian military and naval operations to quell the revolt ended in the Persian reoccupation of Ionian and Greek islands, as well as the re-subjugation of Thrace and the conquering of Macedonia in 492 BCE under Mardonius.[52] Macedon had been a vassal kingdom of the Persians since the late 6th century BCE, but retained autonomy. Mardonius's 492 campaign made it a fully subordinate part of the Persian kingdom.[51] These military actions, coming as a direct response to the revolt in Ionia, were the beginning of the First Persian invasion of (mainland) Greece. At the same time, anti-Persian parties gained more power in Athens, and pro-Persian aristocrats were exiled from Athens and Sparta.

Darius responded by sending troops led by his son-in-law across the Hellespont. However, a violent storm and harassment by the Thracians forced the troops to return to Persia. Seeking revenge on Athens and Eretria, Darius assembled another army of 20,000 men under his Admiral, Datis, and his nephew Artaphernes, who met success when they captured Eretria and advanced to Marathon. In 490 BCE, at the Battle of Marathon, the Persian army was defeated by a heavily armed Athenian army, with 9,000 men who were supported by 600 Plataeans and 10,000 lightly armed soldiers led by Miltiades. The defeat at Marathon marked the end of the first Persian invasion of Greece. Darius began preparations for a second force which he would command, instead of his generals; however, before the preparations were complete, Darius died, thus leaving the task to his son Xerxes.[7]

FamilyDarius was the son of Hystaspes and the grandson of Arsames.[53] Darius married Atossa, daughter of Cyrus, with whom he had four sons: Xerxes, Achaemenes, Masistes and Hystaspes. He also married Artystone, another daughter of Cyrus, with whom he had two known sons, Arsames and Gobryas. Darius married Parmys, the daughter of Bardiya, with whom he had a son, Ariomardus. Furthermore, Darius married his niece Phratagune, with whom he had two sons, Abrokomas and Hyperantes. He also married another woman of the nobility, Phaidyme, the daughter of Otanes. It is unknown if he had any children with her. Before these royal marriages, Darius had married an unknown daughter of his good friend and lance carrier Gobryas from an early marriage, with whom he had three sons, Artobazanes, Ariabignes and Arsamenes.[54] Any daughters he had with her are not known. Although Artobazanes was Darius's first-born, Xerxes became heir and the next king through the influence of Atossa; she had great authority in the kingdom as Darius loved her the most of all his wives.

Death and succession Tomb of Darius at Naqsh-e Rostam

Tomb of Darius at Naqsh-e RostamAfter becoming aware of the Persian defeat at the Battle of Marathon, Darius began planning another expedition against the Greek city-states; this time, he, not Datis, would command the imperial armies.[7] Darius had spent three years preparing men and ships for war when a revolt broke out in Egypt. This revolt in Egypt worsened his failing health and prevented the possibility of his leading another army.[7] Soon afterwards, Darius died, after thirty days of suffering through an unidentified illness, partially due to his part in crushing the revolt, at about sixty-four years old.[55] In October 486 BCE, his body was embalmed and entombed in the rock-cut tomb at Naqsh-e Rostam, which he had been preparing.[7] An inscription on his tomb introduces him as "Great King, King of Kings, King of countries containing all kinds of men, King in this great earth far and wide, son of Hystaspes, an Achaemenian, a Persian, son of a Persian, an Aryan, having Aryan lineage."[7] A relief under his tomb portraying equestrian combat was later carved during the reign of the Sasanian King of Kings, Bahram II (r. 274–293 CE).[56]

Xerxes, the eldest son of Darius and Atossa, succeeded to the throne as Xerxes I; before his accession, he had contested the succession with his elder half-brother Artobarzanes, Darius's eldest son, who was born to his first wife before Darius rose to power.[57] With Xerxes's accession, the empire was again ruled by a member of the house of Cyrus.[7]

Government

OrganizationFurther information: Districts of the Achaemenid Empire

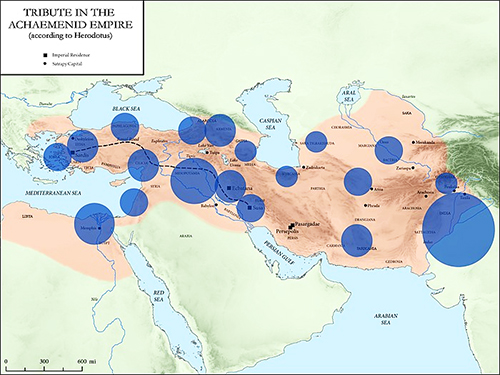

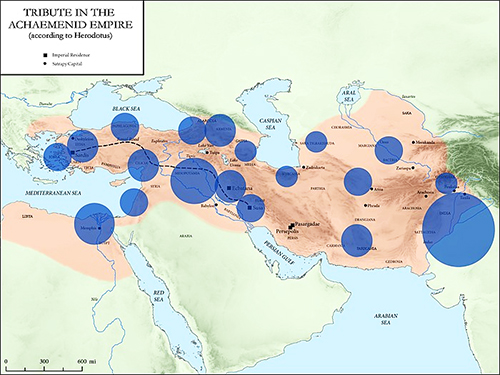

Volume of annual tribute per district, in the Achaemenid Empire.[58][59][60]

Volume of annual tribute per district, in the Achaemenid Empire.[58][59][60]Early in his reign, Darius wanted to reorganize the structure of the empire and reform the system of taxation he inherited from Cyrus and Cambyses. To do this, Darius created twenty provinces called satrapies (or archi) which were each assigned to a satrap (archon) and specified fixed tributes that the satrapies were required to pay.[7] A complete list is preserved in the catalogue of Herodotus, beginning with Ionia and listing the other satrapies from west to east excluding Persis, which was the land of the Persians and the only province which was not a conquered land.[7] Tributes were paid in both silver and gold talents. Tributes in silver from each satrap were measured with the Babylonian talent.[7] Those paid in gold were measured with the Euboic talent.[7] The total tribute from the satraps came to an amount less than 15,000 silver talents.[7]

The majority of the satraps were of Persian origin and were members of the royal house or the six great noble families.[7] These satraps were personally picked by Darius to monitor these provinces. Each of the provinces was divided into sub-provinces, each having its own governor, who was chosen either by the royal court or by the satrap.[7] To assess tributes, a commission evaluated the expenses and revenues of each satrap.[7] To ensure that one person did not gain too much power, each satrap had a secretary, who observed the affairs of the state and communicated with Darius; a treasurer, who safeguarded provincial revenues; and a garrison commander, who was responsible for the troops.[7] Additionally, royal inspectors, who were the "eyes and ears" of Darius, completed further checks on each satrap.[7]

The imperial administration was coordinated by the chancery with headquarters at Persepolis, Susa, and Babylon with Bactria, Ecbatana, Sardis, Dascylium and Memphis having branches.[7] Darius kept Aramaic as the common language, which soon spread throughout the empire.[7] However, Darius gathered a group of scholars to create a separate language system only used for Persis and the Persians, which was called Aryan script and was only used for official inscriptions.[7] Before this, the accomplishments of the king were addressed in Persian solely through narration and hymns and through the "masters of memory".[61] Indeed, oral history continued to play an important role throughout the history of Iran.[61]

EconomySee also: Achaemenid coinage

Gold daric, minted at Sardis

Gold daric, minted at SardisDarius introduced a new universal currency, the daric, sometime before 500 BCE.[7] Darius used the coinage system as a transnational currency to regulate trade and commerce throughout his empire. The Daric was also recognized beyond the borders of the empire, in places such as Celtic Central Europe and Eastern Europe. There were two types of darics, a gold daric and a silver daric. Only the king could mint gold darics. Important generals and satraps minted silver darics, the latter usually to recruit Greek mercenaries in Anatolia. The daric was a major boost to international trade. Trade goods such as textiles, carpets, tools and metal objects began to travel throughout Asia, Europe and Africa. To further improve trade, Darius built the Royal Road, a postal system and Phoenician-based commercial shipping.

The daric also improved government revenues as the introduction of the daric made it easier to collect new taxes on land, livestock and marketplaces. This led to the registration of land which was measured and then taxed. The increased government revenues helped maintain and improve existing infrastructure and helped fund irrigation projects in dry lands. This new tax system also led to the formation of state banking and the creation of banking firms. One of the most famous banking firms was Murashu Sons, based in the Babylonian city of Nippur.[62] These banking firms provided loans and credit to clients.[63]

In an effort to further improve trade, Darius built canals, underground waterways and a powerful navy.[7] According to Herodotus, qanat irrigation technology was introduced to Egypt, which is supported by the historian Albert T. Olmstead.[64] He further improved and expanded the network of roads and way stations throughout the empire, so that there was a system of travel authorization for the King, satraps and other high officials, which entitled the traveller to draw provisions at daily stopping places.[65][7]

Religion"By the grace of Ahuramazda am I king; Ahuramazda has granted me the kingdom."

— Darius, on the Behistun Inscription

Darius at Behistun Darius on the Behistun Inscription reliefs

Darius on the Behistun Inscription reliefs Crowned head of Darius at Behistun

Crowned head of Darius at BehistunWhile there is no general consensus in scholarship whether Darius and his predecessors had been influenced by Zoroastrianism,[66] it is well established that Darius was a firm believer in Ahura Mazda, whom he saw as the supreme deity.[66][67] However, Ahura Mazda was also worshipped by adherents of the (Indo-)Iranian religious tradition.[66][68] As can be seen at the Behistun Inscription, Darius believed that Ahura Mazda had appointed him to rule the Achaemenid Empire.[7]

Darius had dualistic philosophical convictions and believed that each rebellion in his kingdom was the work of druj, the enemy of Asha. Darius believed that because he lived righteously by Asha, Ahura Mazda supported him.[69] In many cuneiform inscriptions denoting his achievements, he presents himself as a devout believer, perhaps even convinced that he had a divine right to rule over the world.[70] However, his relationship with the deity was far more complex: in one inscription he writes "Ahura Mazda is mine, I am Ahura Mazda's".

In the lands that were conquered by his empire, Darius followed the same Achaemenid tolerance that Cyrus had shown and later Achaemenid kings would show.[7] He supported faiths and religions that were "alien" as long as the adherents were "submissive and peaceable", sometimes giving them grants from his treasury for their purposes.[7][71] He had funded the restoration of the Israelite temple which had originally been decreed by Cyrus, was supportive towards Greek cults which can be seen in his letter to Gadatas, and supported Elamite priests.[7] He had also observed Egyptian religious rites related to kingship and had built the temple for the Egyptian god, Amun.[7]

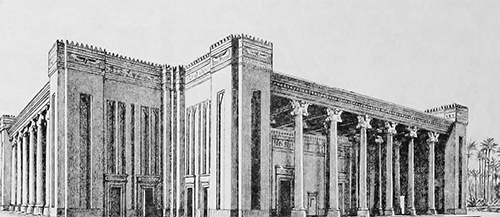

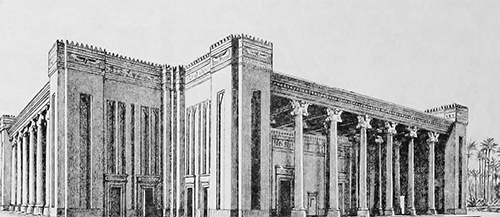

Building projects Reconstruction drawing of the Palace of Darius in Susa

Reconstruction drawing of the Palace of Darius in Susa The ruins of Tachara palace in Persepolis

The ruins of Tachara palace in PersepolisEarly on, Darius and his advisors had the idea to establish new royal mansions at Susa and Persepolis because he was eager to demonstrate his newfound power and leave a lasting legacy. Since Cyrus's conquest, Susa's urban layout had remained unchanged, maintaining the layout from the Elamite era. Only during Darius's rule does the archeological evidence at Susa start showing any signs of a Achaemenid layout.[72]

During Darius's Greek expedition, he had begun construction projects in Susa, Egypt and Persepolis. The Darius Canal that connected the Nile to the Red Sea was constructed by him. It ran from present-day Zagazig in the eastern Nile Delta through Wadi Tumilat, Lake Timsah, and Great Bitter Lake, which are both close to present-day Suez. To open this canal, he travelled to Egypt in 497 BCE, where the inauguration was carried out with great fanfare and celebration. Darius also built a canal to connect the Red Sea and Mediterranean.[7][73] On this visit to Egypt he erected monuments and executed Aryandes on the charge of treason. When Darius returned to Persis, he found that the codification of Egyptian law had been finished.[7]

In Egypt, Darius built many temples and restored those that had previously been destroyed. Even though Darius was a believer of Ahura Mazda, he built temples dedicated to the Gods of the Ancient Egyptian religion. Several temples found were dedicated to Ptah and Nekhbet. Darius also created several roads and routes in Egypt. The monuments that Darius built were often inscribed in the official languages of the Persian Empire, Old Persian, Elamite and Babylonian and Egyptian hieroglyphs. To construct these monuments, Darius employed a large number of workers and artisans of diverse nationalities. Several of these workers were deportees who had been employed specifically for these projects. These deportees enhanced the empire's economy and improved inter-cultural relations.[7] At the time of Darius's death construction projects were still under way. Xerxes completed these works and in some cases expanded his father's projects by erecting new buildings of his own.[74]

Egyptian statue of Darius I, as Pharaoh of the Twenty-seventh Dynasty of Egypt;[75] 522–486 BCE; greywacke; height: 2.46 m;[55] National Museum of Iran (Teheran)

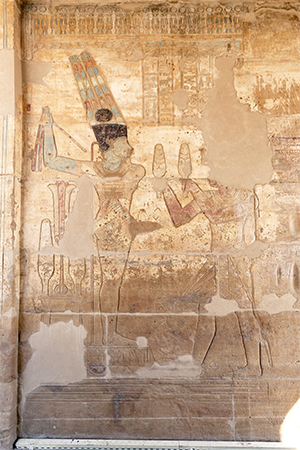

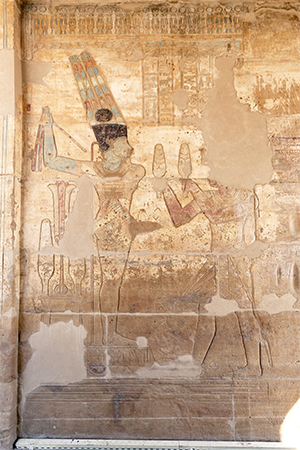

Egyptian statue of Darius I, as Pharaoh of the Twenty-seventh Dynasty of Egypt;[75] 522–486 BCE; greywacke; height: 2.46 m;[55] National Museum of Iran (Teheran) Darius as Pharaoh of Egypt at the Temple of Hibis

Darius as Pharaoh of Egypt at the Temple of Hibis  Relief showing Darius I offering lettuces to the Egyptian deity Amun-Ra Kamutef, Temple of HibisSee also

Relief showing Darius I offering lettuces to the Egyptian deity Amun-Ra Kamutef, Temple of HibisSee also• History portal

• Iran portal

• Biography portal

• Dariush

• Darius the Mede

• List of biblical figures identified in extra-biblical sources

Notes1. According to Herodotus, Hystaspes was the satrap of Persis, although the French Iranologist Pierre Briant states that this is an error.[16] Richard Stoneman likewise considers Herodotus's account to be incorrect.[17]

References1. "DĀḠESTĀN". Retrieved 29 December 2014.

2. Suny, Ronald Grigor (1994). The Making of the Georgian Nation. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-20915-3. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

3. Pollard, Elizabeth (2015). Worlds Together, Worlds Apart concise edition vol.1. New York: W. W. Norton. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-393-25093-0.

4. Schmitt 1994, p. 40.

5. Duncker 1882, p. 192.

6. Egerton 1994, p. 6.

7. Shahbazi 1994, pp. 41–50.

8. Kuhrt 2013, p. 197.

9. Frye 1984, p. 103.

10. Schmitt 1994, p. 53.

11. Zournatzi, Antigoni (2003). "The Apadana Coin Hoards, Darius I, and the West". American Journal of Numismatics. 15: 1–28. JSTOR 43580364.

12. Persepolis : discovery and afterlife of a world wonder. 2012. pp. 171–181.

13. "Behistun, minor inscriptions - Livius".

http://www.livius.org.

14. Llewellyn-Jones 2013, p. 112.

15. Stoneman 2015, p. 189.

16. Briant 2002, p. 467.

17. Stoneman 2015, p. 20.

18. Cook 1985, p. 217.

19. Abbott 2009, p. 14.

20. Abbott 2009, p. 14–15.

21. Abbott 2009, p. 15–16.

22. Boardman 1988, p. 54.

23. "cylinder seal | British Museum". The British Museum.

24. "Darius' seal, photo - Livius".

http://www.livius.org.

25. "The Darius Seal". British Museum.

26. Poolos 2008, p. 17.

27. Abbott 2009, p. 98.

28. Llewellyn-Jones 2017, p. 70.

29. Van De Mieroop 2003.

30. Allen, Lindsay (2005), The Persian Empire, London: The British Museum press, p. 42.

31. Waters 1996, pp. 11, 18.

32. Briant 2002, p. 115.

33. Briant 2002, pp. 115–116.

34. Briant 2002, p. 116.

35. Briant 2002, p. 131.

36. Abbott 2009, p. 99–101.

37. Goodnick Westenholz, Joan (2002). "A Stone Jar with Inscriptions of Darius I in Four Languages" (PDF). ARTA: 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2018.

38. Qahéri, Sépideh (2020). "Alabastres royaux d'époque achéménide". L’Antiquité à la BnF (in French). doi:10.58079/b8of.

39. Del Testa 2001, p. 47.

40. Abbott 2009, p. 129.

41. Sélincourt 2002, pp. 234–235.

42. Siliotti 2006, pp. 286–287.

43. Woolf et al. 2004, p. 686.

44. Miroslav Ivanov Vasilev. "The Policy of Darius and Xerxes towards Thrace and Macedonia" ISBN 90-04-28215-7 p. 70

45. Ross & Wells 2004, p. 291.

46. Beckwith 2009, pp. 68–69.

47. Boardman 1982, pp. 239–243.

48. Herodotus 2015, pp. 352.

49. Chaliand 2004, p. 16.

50. Grousset 1970, pp. 9–10.

51. Joseph Roisman, Ian Worthington. "A companion to Ancient Macedonia" John Wiley & Sons, 2011. ISBN 1-4443-5163-X pp. 135–138, 343

52. Joseph Roisman; Ian Worthington (2011). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 135–138. ISBN 978-1-4443-5163-7.

53. Briant 2002, p. 16.

54. Briant 2002, p. 113.

55. livius.org (2017). Darius the Great: Death. Thames & Hudson. p. 280. ISBN 978-0-500-20428-3.

56. Shahbazi 1988, pp. 514–522.

57. Briant 2002, p. 136.

58. Herodotus Book III, 89–95

59. Archibald, Zosia; Davies, John K.; Gabrielsen, Vincent (2011). The Economies of Hellenistic Societies, Third to First Centuries BC. Oxford University Press. p. 404. ISBN 978-0-19-958792-6.

60. "India Relations: Achaemenid Period – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org.

61. Briant 2002, pp. 126–127.

62. Farrokh 2007, p. 65.

63. Farrokh 2007, pp. 65–66.

64. Olmstead, A. T. (1948). History of the Persian Empire (PDF). The University of Chicago Press. p. 224. ISBN 0-226-62777-2.

65. Konecky 2008, p. 86.

66. Malandra 2005.

67. Briant 2002, p. 126.

68. Boyce 1984, pp. 684–687.

69. Boyce 1979, p. 55.

70. Boyce 1979, pp. 54–55.

71. Boyce 1979, p. 56.

72. Briant 2002, p. 165.

73. Spielvogel 2009, p. 49.

74. Boardman 1988, p. 76.

75. Razmjou, Shahrokh (1954). Ars orientalis; the arts of Islam and the East. Freer Gallery of Art. pp. 81–101.

Bibliography• Abbott, Jacob (2009), History of Darius the Great: Makers of History, Cosimo, Inc., ISBN 978-1-60520-835-0

• Abbott, Jacob (1850), History of Darius the Great, New York: Harper & Bros

• Balentine, Samuel (1999), The Torah's vision of worship, Minneapolis: Fortress Press, ISBN 978-0-8006-3155-0

• Beckwith, Christopher (2009), Empires of the Silk Road: a history of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the present (illustrated ed.), Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13589-2

• Bedford, Peter (2001), Temple restoration in early Achaemenid Judah (illustrated ed.), Leiden: Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-11509-5

• Bennett, Deb (1998), Conquerors: The Roots of New World horsemanship, Solvang, CA: Amigo Publications, Inc., ISBN 978-0-9658533-0-9

• Boardman, John (1988), The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. IV (2nd ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-22804-6

• Boardman, John, ed. (1982). The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 10: Persia, Greece, and the Western Mediterranean. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 239–243. ISBN 978-0-521-22804-6.

• Boyce, Mary (1979). Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. Psychology Press. pp. 1–252. ISBN 978-0-415-23902-8.

• Boyce, M. (1984). "Ahura Mazdā". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. I, Fasc. 7. pp. 684–687.

• Briant, Pierre (2002). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Eisenbrauns. pp. 1–1196. ISBN 978-1-57506-120-7.

• Chaliand, Gérard (2004), Nomadic empires: from Mongolia to the Danube (illustrated, annotated ed.), Transaction Publishers, ISBN 978-0-7658-0204-0

• Cook, J. M. (1985), "The Rise of the Achaemenids and Establishment of their Empire", The Median and Achaemenian Periods, Cambridge History of Iran, vol. 2, London: Cambridge University Press

• Del Testa, David (2001), Government leaders, military rulers, and political activists (illustrated ed.), Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-1-57356-153-2

• Duncker, Max (1882), Evelyn Abbott (ed.), The history of antiquity (Volume 6 ed.), R. Bentley & son

• Egerton, George (1994), Political memoir: essays on the politics of memory, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-7146-3471-5

• Frye, Richard Nelson (1984). The History of Ancient Iran. C.H.Beck. pp. 1–411. ISBN 978-3-406-09397-5.

• Farrokh, Kaveh (2007), Shadows in the desert: ancient Persia at war, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84603-108-3[permanent dead link]

• Grousset, René (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. Rutgers University Press. pp. 1–687. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

• Herodotus, ed. (2015). The Histories. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 352. ISBN 978-0-375-71271-5.

• Konecky, Sean (2008), Gidley, Chuck (ed.), The Chronicle of World History, Old Saybrook, CT: Grange Books, ISBN 978-1-56852-680-5

• Kuhrt, A. (2013). The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-01694-3.

• Llewellyn-Jones, Lloyd (2013). King and Court in Ancient Persia 559 to 331 BCE. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–272. ISBN 978-0-7486-7711-5.

• Llewellyn-Jones, Lloyd (2017). "The Achaemenid Empire". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.). King of the Seven Climes: A History of the Ancient Iranian World (3000 BCE – 651 CE). UCI Jordan Center for Persian Studies. pp. 1–236. ISBN 978-0-692-86440-1.

• Malandra, William W. (2005). "Zoroastrianism i. Historical review up to the Arab conquest". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

• Moulton, James (2005), Early Zoroastrianism, Kessinger Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4179-7400-9[permanent dead link]

• Poolos, J (2008), Darius the Great (illustrated ed.), Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7910-9633-8

• Ross, William; Wells, H. G. (2004), The Outline of History: Volume 1 (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading): Prehistory to the Roman Republic (illustrated ed.), Barnes & Noble Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7607-5866-3, retrieved 28 July 2011

• Safra, Jacob (2002), The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica Inc, ISBN 978-0-85229-787-2

• Schmitt, Rudiger (1994). "Darius I. The Name". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VII, Fasc. 1. p. 40.

• Sélincourt, Aubrey (2002), The Histories, London: Penguin Classics, ISBN 978-0-14-044908-2

• Shahbazi, A. Shapur (1988). "Bahrām II". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 5. pp. 514–522.

• Shahbazi, Shapur (1994), "Darius I the Great", Encyclopedia Iranica, vol. 7, New York: Columbia University, pp. 41–50

• Siliotti, Alberto (2006), Hidden Treasures of Antiquity, Vercelli, Italy: VMB Publishers, ISBN 978-88-540-0497-9

• Spielvogel, Jackson (2009), Western Civilization: Seventh edition, Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth, ISBN 978-0-495-50285-2

• Stoneman, Richard (2015). Xerxes: A Persian Life. Yale University Press. pp. 1–288. ISBN 978-1-57506-120-7.

• Tropea, Judith (2006), Classic Biblical Baby Names: Timeless Names for Modern Parents, New York: Bantam Books, ISBN 978-0-553-38393-5

• Van De Mieroop, Marc (2003), A History of the Ancient Near East: Ca. 3000–323 BC, "Blackwell History of the Ancient World" series, Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-631-22552-2

• Waters, Matt (1996). "Darius and the Achaemenid Line". The Ancient History Bulletin. 10 (1). London: 11–18.

• Waters, Matt (2014). Ancient Persia: A Concise History of the Achaemenid Empire, 550–330 BCE. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–272. ISBN 978-1-107-65272-9.

• Woolf, Alex; Maddocks, Steven; Balkwill, Richard; McCarthy, Thomas (2004), Exploring Ancient Civilizations (illustrated ed.), Marshall Cavendish, ISBN 978-0-7614-7456-2

Further reading Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article "Darius".

• Burn, A.R. (1984). Persia and the Greeks : the defence of the West, c. 546–478 B.C (2nd ed.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-1235-4.

• Ghirshman, Roman (1964). The Arts of Ancient Iran from Its Origins to the Time of Alexander the Great. New York: Golden Press.

• Hyland, John O. (2014). "The Casualty Figures in Darius' Bisitun Inscription". Journal of Ancient Near Eastern History. 1 (2): 173–199. doi:10.1515/janeh-2013-0001. S2CID 180763595.

• Klotz, David (2015). "Darius I and the Sabaeans: Ancient Partners in Red Sea Navigation". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 74 (2): 267–280. doi:10.1086/682344. S2CID 163013181.

• Olmstead, Albert T. (1948). History of the Persian Empire, Achaemenid Period. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

• Vogelsang, W.J. (1992). The rise and organisation of the Achaemenid Empire : the eastern Iranian evidence. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09682-0.

• Warner, Arthur G. (1905). The Shahnama of Firdausi. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner and Co.

• Wiesehöfer, Josef (1996). Ancient Persia : from 550 BC to 650 AD. Azizeh Azodi, trans. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-85043-999-8.

• Wilber, Donald N. (1989). Persepolis : the archaeology of Parsa, seat of the Persian kings (Rev. ed.). Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press. ISBN 978-0-87850-062-8.