by Rohan Singh

January 4, 2023

https://www.viewsnews.net/2023/01/04/da ... -imagined/

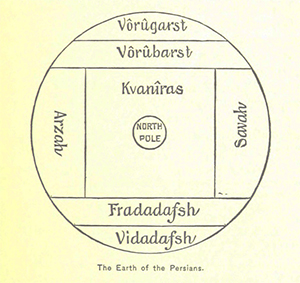

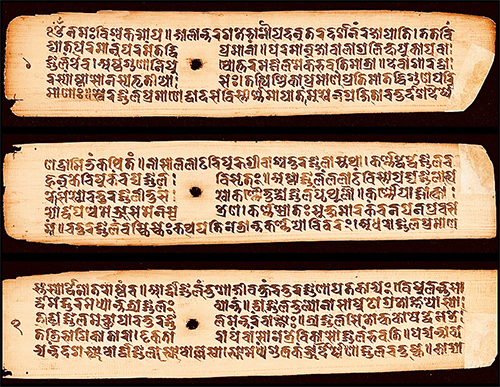

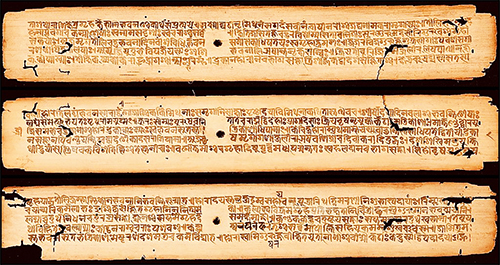

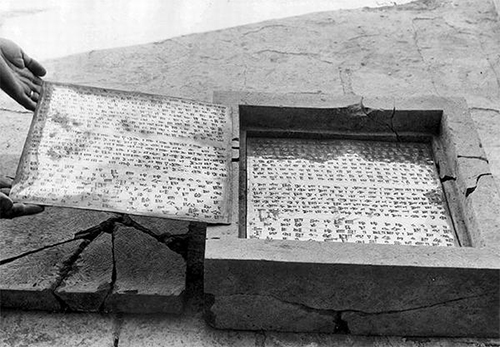

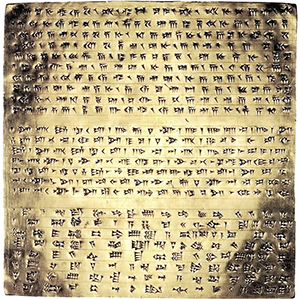

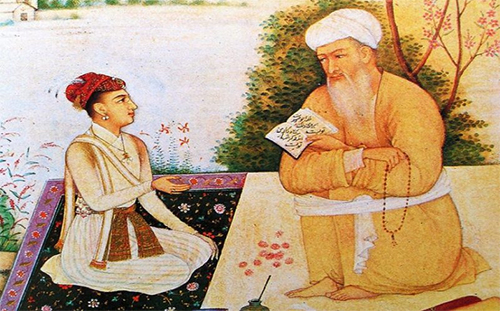

-- Oupnek'hat [Four Upanishads], by Anquetil Duperron. [Dara Shako (Mohammed Dara Shikuh, 1615-59), the eldest son of Shahdjehan, shows publicly his indifference for Islam. In Delhi in 1656, this prince has brahmins of Benares translate the Oupnekat, a Sanskrit work whose name signifies The Word that must not be enounced (the secret that must not be revealed). This work is the essence of the four Vedas. It presents in 51 sections the complete system of Indian theology of which the result is the unity of the supreme Being [premier Etre] whose perfections and personified operations have the name of the principal Indian divinities, and the reunion [reunion] of the entire nature with this first Agent. -- by Anquetil Duperron, 1802]

-- Travels in the Mogul Empire, A.D. 1656-1668, by Francois Bernier, M.D., of the Faculty of Montpellier, Translated on the Basis of Irving Brock's Version & Annotated by Archibald Constable, 1891. Second Edition Revised by Vincent A. Smith, M.A., Author of 'The Early History of India,' etc., 1916

During the Fall 2022 semester, I had the pleasure of taking a course titled “The World of Islam,” taught by Ambassador Akbar Ahmed, an American-Pakistani academic, author, poet, playwright, filmmaker, former Pakistan High Commissioner to the UK and Ireland, Wilson Center Global Fellow, and the Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies at American University. One of my personal highlights of the course was Dr. Ahmed’s play The Trial of Dara Shikoh, a historical reimagining of Prince Dara Shikoh’s execution and Aurangzeb’s rise to the Mughal throne in the 17th century. But what does a play about 17th-century royalty have to do with the world of Islam today? The Trial of Dara Shikoh envisions Prince Dara as a tragic hero with a timeless message for unity, not only in India but among all the world’s faiths. In this article, I will discuss the historical and modern significance of Dara Shikoh’s message in times of increasing religious conflict and what Dara Shikoh means to me as a South Asian American.

The Historical Significance of Dara Shikoh

Shah Jehan was one of the mighty emperors of the Mughal Empire. His name is easily recognized by many as he commissioned the Taj Mahal as a tomb for his beloved wife, Mumtaz Mahal. Prince Dara Shikoh was the eldest son of Emperor Shah Jehan and was therefore named heir apparent to the Mughal throne.

The Taj Mahal; lit. 'Crown of the Palace'

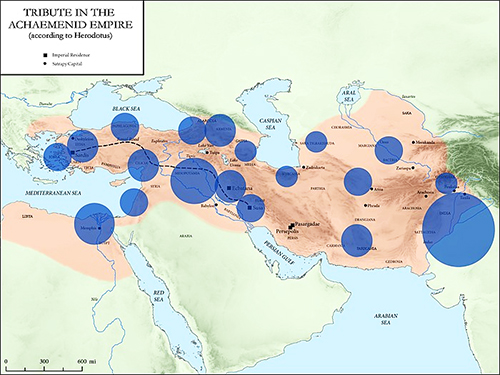

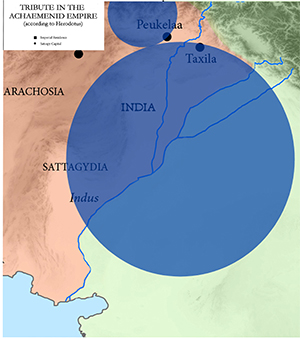

During this period, Muslim empires like the Ottomans and Safavids held great power, but none were as wealthy and prosperous as the Mughal Empire at its peak, which accounted for a quarter of the world’s GDP. However, the 17th century was a key turning point for many civilizations as European colonists started traveling and surveying land to conquer. Whether India would be the next land conquered or not would depend on the Mughals holding on to their power.

India has always been a very complex mix of cultures and religions, which at times led to tensions. Early Mughals had imposed a tax for non-Muslims, which essentially was an indirect way to encourage conversion. Under Emperor Akbar, the Great, Shah Jehan’s father, abolished this tax as a way of promoting unity in the empire after marrying a Rajput Hindu Princess, Jodha Bai. Akbar knew unity between India’s religious communities was key in maintaining power and protecting the empire from invasion.

Dara Shikoh, like his grandfather Emperor Akbar, was very interested in maintaining unity and even went the distance to understand his soon-to-be subjects. Dara Shikoh was responsible for the first-ever translation of the Hindu text of the Upanishads into Persian and also translated the Bhagavad Gita, thus allowing both texts to be introduced to the world (Ahmed). He was well-liked by mystics of all religions, and many awaited Dara Shikoh’s ascension to the throne, given his ideology toward unification (Ahmed).

... the Sufi-Vedanta-Neoplatonic amalgam of Prince Dara as reported by Bernier ...Dara [Shikoh] was not deficient in good qualities: he was courteous in conversation, quick at repartee, polite, and extremely liberal but he entertained too exalted an opinion of himself; believed he could accomplish everything by the powers of his own mind, and imagined that there existed no man from whose counsel he could derive benefit. He spoke disdainfully of those who ventured to advise him, and thus deterred his sincerest friends from disclosing the secret machinations of his brothers. He was also very irascible; apt to menace; abusive and insulting even to the greatest Omrahs; but his anger was seldom more than momentary. Born a Mahometan, he continued to join in the exercises of that religion; but although thus publicly professing his adherence to its faith. Dara was in private a Gentile with Gentiles, and a Christian with Christians. He had constantly about him some of the Pendets, or Gentile Doctors, on whom he bestowed large pensions, and from these it is thought he imbibed opinions in no wise accordant with the religion of the land but upon this subject I shall make a few observations when I treat of the religious worship of the Indous or Gentiles. He had, moreover, for some time lent a willing ear to the suggestions of the Reverend Father Buzee, a Jesuit, in the truth and propriety of which he began to acquiesce. 1 [Catrou in his History of the Mogul Dynasty in India, Paris, 1715, which is largely based upon the materials collected by Signer Manouchi, a Venetian, who was for forty-eight years a Physician at the Courts of Delhi and Agra, and for some time attached to Dara’s person, says that ‘no sooner had Dara begun to possess authority, than he became disdainful and inaccessible. A small number of Europeans alone shared his confidence. The Jesuits, especially, were in the highest consideration with him. These were the Fathers . . . and Henry Busee, a Fleming. This last had much influence over the mind of the prince, and had his counsels been followed, it is probable that Christianity would have mounted the throne with Dara.’] There are persons, however, who say that Dara was in reality destitute of all religion, and that these appearances were assumed only from motives of curiosity, and for the sake of amusement; while, according to others, he became by turns a Christian and a Gentile from political considerations; wishing to ingratiate himself with the Christians who were pretty numerous in his corps of artillery, and also hoping to gain the affection of the Rajas, or Gentile Princes tributary to the empire; as it was most essential to be on good terms with these personages, that he might, as occasion arose, secure their co-operation. Darn's false pretences to this or that mode of worship, did not, however, promote the success of his plans; on the contrary, it will be found in the course of this narrative, that the reason assigned by Aureng-Zebe for causing him to be beheaded was, that he had turned Kafer, that is to say an infidel, without religion, an idolater..........

Do not be surprised if, notwithstanding my ignorance of Sanscrit 2 ['Hanscrit' in the original, see p. 329, footnote 3.] (the language of the learned, and possibly that of the ancient Brahmens, as we may learn further on), I yet say something of books written in that tongue. My Agah, Danechmend-kan, partly from my solicitation and partly to gratify his own curiosity, took into his service one of the most celebrated Pendets in all the Indies, who had formerly belonged to the household of Dara, 3 [Dara Shikoh, when Governor or Viceroy of Benares, in 1656, caused a Persian translation to be made from the Sanskrit text of the Upanishads ('the word that is not to be revealed'), which he called the Sarr-i-Asrar, or Secret of Secrets. This translation, which was made by a large staff of Benares Pandits, has been rendered into Latin by Anquetil-Duperron, and published by him at Paris, 1801, under the title of Oupnekhat (id est, Secretum Tegendum) opus ipsa in India rarissimum, etc. etc. His version is criticised in an article published in the second number (January 1803) of The Edinburgh Review, which I believe to have been written by Alexander Hamilton, 'a Scotchman who had been in India; . . . of excellent conversation and great knowledge of Oriental literature. He was afterwards professor of Sanscrit' [in the official lists he is designated Professor of Hindu Literature and History of Asia] 'in the East India College at Haileybury,' p. 141, vol. i. Cockburn's Life of Lord Jeffrey, Edin. 1852, also see p. 256, vol. i. of Lord Brougham's Life and Times, Edin. and Lond. 1871. In this critique pleasing testimony is borne to the great abilities of Prince Dara Shikoh, as follows: — 'If intolerance and fanaticism be the usual concomitants of Islamism (an assertion, we think, too generally expressed), the descendants of Tamerlane, who reigned in Hindustan, furnish some remarkable exceptions to the received opinion. At the head of these illustrious personages we should, perhaps, place Dara Shecuh, the eldest son of the Emperor Shah Gehan. The attention which this Prince bestowed, investigating the antique dogmas of the Hindu theology, and the munificence with which he rewarded the learned Brahmans, whom he collected from all parts of the empire, furnished his brother Aurengzebe with a pretext to misrepresent his motives, and to alarm the zealous Moslems with the danger of an apostate succeeding to the throne. The melancholy catastrophe which ensued; the death of the unhappy Dara, with the long and brilliant reign of the successful hypocrite, who founded his greatness on the destruction of his brothers, are detailed in the page of history. If the sceptical philosopher be disposed to exclaim with the Roman Epicurean, 'Tanta Religio potuit suadere malorum,' we must state our conviction that ambition, not fanaticism, prompted the deed; though the steps by which he mounted the throne threw the rigid veil of superstition over the subsequent conduct of Aurengzebe, and gave that tone to his court.'] the eldest son of the King Chah-Jehan; and not only was this man my constant companion during a period of three years, but he also introduced me to the society of other learned Pendets, whom he attracted to the house. When weary of explaining to my Agah the recent discoveries of Harveus and Pecquet in anatomy, and of discoursing on the philosophy of Gassendi and Descartes, 1 [FN1]FN1: William Harvey, born in 1578, and died in 1657. It was in 1616, the year of Shakespeare's death, that he began his course of lectures to the Royal College of Physicians in London, and formally announced his discovery of the circulation of the blood, which has rendered his name for ever famous.

Jean Pecquet, born at Dieppe, in France, in 1622, died in 1674. He studied medicine at Montpellier, where Bernier was also a student, and it was there that he prosecuted those investigations which led to his discoveries, in connection with the conversion of the chyle into blood, which have immortalised his name.

Rene Descartes, born at La Haye, Touraine, in France, in 1596, and died at Stockholm in 1650.

which I translated to him in Persian (for this was my principal employment for five or six years) we had generally recourse to our Pendet, who, in his turn, was called upon to reason in his own manner, and to communicate his fables; these he related with all imaginable gravity without ever smiling; but at length we became disgusted both with his tales and childish arguments. ............

In conclusion, I shall explain to you the Mysticism of a Great Sect 1 [In the original, 'le mystere d'une grande Cabale.'] which has latterly made great noise in Hindoustan, inasmuch as certain Pendets or Gentile Doctors had instilled it into the minds of Dara and Sultan Sujah, the elder sons of Chah-Jehan. 2 [FN2]FN2: Mirza Muhammad Kazim, the historian, in his Alamgir Nama, which is a history of the first ten years of the reign of the Emperor Alamgir (Aurangzeb), written in 1688, treats of the heresy of Dara Shikoh as follows —

'Dara Shukoh in his later days did not restrain himself to the free-thinking and heretical notions which he had adopted under the name of Tasawwuf (Sufism), but showed an inclination for the religion and institutions of the Hindus. He was constantly in the society of Brahmans, Jogis, and Sannyasis, and he used to regard these worthless teachers of delusions as learned and true masters of wisdom. He considered their books, which they call Bed, as being the Word of God and revealed from Heaven, and he called them ancient and excellent books. He was under such delusion about this Bed that he collected Brahmans and Sannyasis from all parts of the country, and paying them great respect and attention, he employed them in translating the Bed. He spent all his time in this unholy work, and devoted all his attention to the contents of these wretched books. . . . Through these perverted opinions he had given up the prayers, fasting, and other obligations imposed by the law. ... It became manifest that if Dara Shukoh obtained the throne and established his power, the foundations of the faith would be in danger and the precepts of Islam would be changed for the rant of infidelity and Judaism.'— Elliot, History of India, vol. vii. page 179. For a definition of Sufism, which is and always has been looked upon as rank heresy by orthodox Moslems, see p. 320, footnote 2. Sannyasi is the name in modern times for various sects of Hindoo religious mendicants who wander about and subsist upon alms; the 'naked Fakires' described by Bernier (p. 317), of whom Sarmet was one. According to the laws of Manu, the life of a Brahman was divided into four stages, the fourth of which was that of a Sannyasi. ' The religious mendicant who, freed from all forms and observances, wanders about and subsists on alms, practising or striving for that condition of mind which, heedless of the flesh, is intent only upon the Deity and final absorption.'— Dowson, Classical Diet, of Hindu Mythology, London, 1879. [END FN]

You are doubtless acquainted with the doctrine of many of the ancient philosophers concerning that great life-giving principle of the world, of which they argue that we and all living creatures are so many parts if we carefully examine the writings of Plato and Aristotle, we shall probably discover that they inclined towards this opinion. This is the almost universal doctrine of the Gentile Pendets of the Indies, and it is this same doctrine which is held by the sect of the Soufys and the greater part of the learned men of Persia at the present day, and which is set forth in Persian poetry in very exalted and emphatic language, in their Goul-tchen-raz, 1 [FN1]FN1: The Gulshan Raz, or 'Mystic Rose Garden,' was composed in 717 A.H. (1317 A.D.) in answer to fifteen questions on the doctrines of the Sufis propounded by Amir Syad Hosaini, a celebrated Sufi of Khorasan. Hardly anything is known of the author, Muhammad Shabistari, further than that he was born at Shabistar, a village in Azarbaijan, and that he wrote this poem and died at Tabriz, the capital town of the same province, in 720 A.H. = 1320 A.D. 'To the European reader the Gulshan Raz is useful as being one of the clearest explanations of that peculiar phraseology which pervades Persian poetry, and without a clear understanding of which it is impossible to appreciate that poetry as it deserves. And it is also interesting as being one of the most articulate expressions of "Sufism," that remarkable phrase of Muhammadan religious thought which corresponds to the mysticism of European theology.' See the Gulshan Raz of Najm ud din, otherwise called Sa'd ud din Mahmud Shabistari Tabrizi. Translated by E. H. Whinfield, M.A., of the Bengal Civil Service. Wyman and Co., Publishers, Hare Street, Calcutta, 1876. [END FN1]

or Garden of Mysteries. This was also the opinion of Flud 2 [FN2]FN2: Robert Flud, or Fludd, Physician, healer by 'faith-natural,' and Rosicrucian, was born at Bearsted in Kent in 1574, and died in London, 1637. He is the chief English representative of that school of medical mystics who laid claim to the possession of the key to universal science, and his voluminous writings on things divine and human, attracted more attention abroad than in his own country. Gassendi's contribution to the controversy was his Examen Philosophiae Fluddanae, published in 1633, and an earlier treatise, published in 1631.[END FN2]

whom our great Gassendy has so ably refuted; and it is similar to the doctrines by which most of our alchymists have been hopelessly led astray. Now these Sectaries or Indou Pendets, so to speak, push the incongruities in question further than all these philosophers, and pretend that God, or that supreme being whom they call Achar l [See p. 325.] (immovable, unchangeable) has not only produced life from his own substance, but also generally everything material or corporeal in the universe, and that this production is not formed simply after the manner of efficient causes, but as a spider which produces a web from its own navel, and withdraws it at pleasure. The Creation then, say these visionary doctors, is nothing more than an extraction or extension of the individual substance of God, of those filaments which He draws from his own bowels; and, in like manner, destruction is merely the recalling of that divine substance and filaments into Himself; so that the last day of the world, which they call maperle or pralea, 2 [Maha-pralaya, or total dissolution of the universe at the end of a kalpa (a day and night of Brahma, equal to 4,320,000,000 years) when the seven lokas (divisions of the universe) and their inhabitants, men, saints, gods, and Brahma himself, are annihilated. Pralaya is a modified form of dissolution.] and in which they believe every being will be annihilated, will be the general recalling of those filaments which God had before drawn forth from Himself. — There is, therefore, say they, nothing real or substantial in that which we think we see, hear or smell, taste or touch; the whole of this world is, as it were, an illusory dream, inasmuch as all that variety which appears to our outward senses is but one only and the same thing, which is God Himself; in the same manner as all those different numbers, of ten, twenty, a hundred, a thousand, etc., are but the frequent repetition of the same unit. — But ask them some reason for this idea; beg them to explain how this extraction and reception of substance occurs, or to account for that apparent variety; or how it is that God not being corporeal but biapek, as they allow, and incorruptible, He can be thus divided into so many portions of body and soul, they will answer you only with some fine similes — That God is as an immense ocean in which many vessels of water are in continual motion; let these vessels go where they will, they always remain in the same ocean, in the same water; and if they should break, the water they contain would then be united to the whole, to that ocean of which they were but parts. — Or they will tell you that it is with God as with the light, which is the same everywhere, but causes the objects on which it falls to assume a hundred different appearances, according to the various colours or forms of the glasses through which it passes. — They will never attempt to satisfy you, I say, but with such comparisons as these, which bear no proportion with God, and which serve only to blind an ignorant people. In vain will you look for any solid answer. If one should reply that these vessels might float in a water similar to their own, but not in the same; and that the light all over the world is indeed similar, but not the same, and so on to other strong objections which may be made to their theory, they have recourse continually to the same similes, to fine words, or, in the case of the Soufys, to the beautiful poems of their Goul-tchen-raz.

Now, Sir, what think you? Had I not reason from all this great tissue of extravagant folly on which I have re marked; from that childish panic of which I have spoken above; from that superstitious piety and compassion toward the sun in order to deliver it from the malignant and dark Deuta; from that trickery of prayers, of ablutions, of dippings, and of alms, either cast into the river, or bestowed on Brahmens; from that mad and infernal hardihood of women to burn themselves with the body of those husbands whom frequently they have hated while alive; from those various and frantic practices of the Fakires; and lastly, from all that fabulous trash of their Beths and other books; was I not justified in taking as a motto to this letter, — the wretched fruit of so many voyages and so many reflections, a motto of which the modern satirist has so well known how to catch and convey the idea without so long a journey — 'There are no opinions too extravagant and ridiculous to find reception in the mind of man '?

To conclude, you will do me a kindness by delivering Monsieur Chapelle's 1 [The letter referred to, despatched, as was the present one, from Chiras, but on the 10th June 1668, Concerning his intention of resuming his studies, on some points which relate to the doctrine of atoms, and to the nature of the human understanding, is not printed in this present edition. It contains much curious matter, but nothing directly relating to Bernier's Indian experiences. Claude-Emmanuel Luillier Chapelle (1626-1645) was a natural son of Francois Luillier's, at whose house Gassendi was a frequent guest; struck by the talent of young Chapelle he gave him lessons in philosophy together with Moliere and Bernier.] letter into his own hands; it was he who first obtained for me that acquaintance with your intimate and illustrious friend, Monsieur Gassendi, which has since proved so advantageous to me. I am so much obliged to him for this favour that I cannot but love and remember him wherever my lot may be cast. I also feel myself under much obligation to you, and am bound to honour you all my life, not only on account of the partiality you have manifested toward me, but also for the valuable advice contained in your frequent letters, by which you have aided me during my journeys, and for your goodness in having sent me so disinterestedly and gratuitously a collection of books to the extremity of the world, whither my curiosity had led me; while those of whom I requested them, who might have been paid with money which I had left at Marseilles, and who in common politeness should have sent them, deserted me and laughed at my letters, looking on me as a lost man whom they were never more to see.

-- Travels in the Mogul Empire, A.D. 1656-1668, by Francois Bernier, M.D., of the Faculty of Montpellier, Translated on the Basis of Irving Brock's Version & Annotated by Archibald Constable, 1891. Second Edition Revised by Vincent A. Smith, M.A., Author of 'The Early History of India,' etc., 1916

-- The Birth of Orientalism, by Urs App

-- Oupnek'hat [Four Upanishads], by Anquetil Duperron. [Dara Shako (Mohammed Dara Shikuh, 1615-59), the eldest son of Shahdjehan, shows publicly his indifference for Islam. In Delhi in 1656, this prince has brahmins of Benares translate the Oupnekat, a Sanskrit work whose name signifies The Word that must not be enounced (the secret that must not be revealed). This work is the essence of the four Vedas. It presents in 51 sections the complete system of Indian theology of which the result is the unity of the supreme Being [premier Etre] whose perfections and personified operations have the name of the principal Indian divinities, and the reunion [reunion] of the entire nature with this first Agent. -- by Anquetil Duperron, 1802]

However, Dara Shikoh’s brother Aurangzeb was not going to let that happen and utilized his military and administrative power to defeat his brother and declare himself emperor. Aurangzeb was far more of an orthodox Muslim and according to Dr. Ahmed, “Many powerful Muslim nobles and generals preferred Aurangzeb in order to underline the Islamic nature of the Mughal Empire.” Aurangzeb eventually imprisoned his father in the Agra Fort until his death and executed his brother Dara.

Under Aurangzeb’s rule, the tax on non-Muslims was reinstated along with oppressive policies towards non-Muslim communities. Many stories of Sikh Gurus are about the abuse they faced at the hands of Aurangzeb’s rule, such as Guru Govind Singh’s children being buried alive behind a wall in front of his eyes because he refused to convert. Such incidents led to major tensions between religious groups. However, Aurangzeb was also able to expand the reach of the Mughal empire further than any other previous king, fortifying the empire’s strength.

As I mentioned, this time period put many empires at a crossroads, with Europeans surveying the globe for land and resources. While the strength of the Mughal empire was beyond anyone’s wildest imagination, it does not take much for the house of cards to eventually fall. This clash between the two brother’s conflicting ideologies is a perfect example of just how crucial this period was. We saw what Aurangzeb did and it is possible that Dara Shikoh’s ideology of unification may have helped prevent colonialism or at least made it difficult for colonists to exploit religious tensions in their favor, but we will never know. [???!!!]

A fundamental factor in the premodern European discovery of Asian religions is easily overlooked just because it is so pervasive and determines the outlook of most discoverers: the biblical frame of reference. All religions of the world had to originate with a survivor of the great deluge (usually set circa 2500 B.C.E.) because nobody outside Noah's ark survived. In Roman times, young Christianity was portrayed as the successor of Adam's original pure monotheism, thus stretching its roots into antediluvian times....

After the discovery of America and the opening of the sea route to India at the end of the fifteenth century, new challenges to biblical authority arose. It was difficult to establish a connection between hitherto unknown people and animals and Noah's ark.... Our case studies show different ways in which Europeans tried to rise to such challenges: missionaries who attempted to incorporate ancient Asian cultures and religions into Bible-based scenarios; others who tried to move the starting shot of biblical history backward to beat the Chinese annals...

[F]rom the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries, the doctrines of emanation and transmigration constituted a crucial link between East and West extending from Japan in the Far East ... authors identified transmigration as a most ancient and universal pre-Mosaic teaching concerning the fall of angels before the creation of the earth -- a teaching that in their view forms the initial part of the biblical creation story that Moses omitted. They regarded human souls as the souls of fallen angels imprisoned in human bodies who have to migrate from one body to the next until they achieve redemption and can return to their heavenly home....

[T]wo significations of Buddhist doctrines, an exoteric or outer one for the simple-minded people and an esoteric or inner one for the philosophers and literati ...

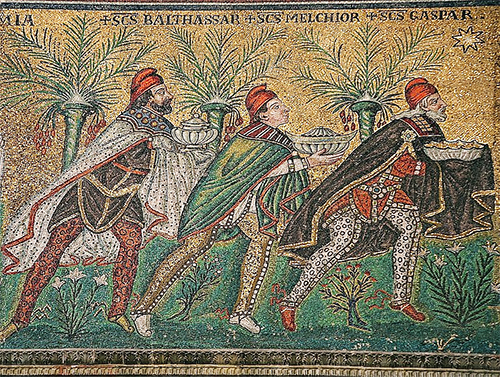

[W]hen Ricci in [1582] moved with another Italian missionary, Michele Ruggieri, to Canton and then to Zhaoqing in South China... the two Jesuits adopted the title and vestments of the Chinese seng -- that is, they identified themselves and dressed as ordained Buddhist bonzes. Even their Ten Commandments in Chinese contained Buddhist terms; for example, the third commandment read that on holidays it was forbidden to work and one had to go to the Buddhist temple (si) in order to recite the sutras (jing) and worship the Master of Heaven (tianzhu, the Lord of devas). Ruggieri's and Ricci's first Chinese catechism, the Tianzhu shilu of 1584-the first book printed by Europeans in China -- also brimmed with Buddhist terms and was signed by "the bonzes from India" (tianzhuguo seng) (Ricci 1942:198). The doorplate of the Jesuit's residence and church read "Hermit-flower [Buddhist] temple" (xianhuasi), while the plate displayed prominently inside the church read "Pure Land of the West" (xilai jingdu). As can be seen in the report about the inscriptions on the Jesuit residence and church of Zhaoqing (Figure 1), Ruggieri translated "hermit" (xian), a term with Daoist connotations, by the Italian "santi" (saints), and the Buddhist temple (St) became an "ecclesia" (church). Even more interesting is his transformation of the Buddhist paradise or "Pure Land of the West" into "from the West came the purest fathers." This presumably referred to the biblical patriarchs, but it is not excluded that a double-entrendre Jesuit fathers from the West) was intended.

Nine years later, in 1592, when Ricci was translating the four Confucian classics, he decided to abandon his identity as a Buddhist bonze (seng); and during a visit in Macao, he asked his superior Valignano for permission also to shed his bonze's robe, begging bowl, and sutra recitation implements. The Christian churches were renamed from si to tang (a more neutral word meaning "hall"), and in 1594 the final step in this rebranding process was taken when Ricci received Valignano's permission to present himself and dress up as a Chinese literatus. It was the year when Ricci finished his translation of the four Confucian classics, the books that any Chinese wishing to reach the higher ranks of society had to study. In Ricci's view, these books contained unmistakable vestiges of ancient monotheism. In his journals he wrote,Of all the pagan sects known to Europe, I know of no people who fell into fewer errors in the early stages of their antiquity than did the Chinese. From the very beginning of their history it is recorded in their writings that they recognized and worshipped one supreme being whom they called the King of Heaven, or designated by some other name indicating his rule over heaven and earth .... They also taught that the light of reason came from heaven and that the dictates of reason should be hearkened to in every human action....

Ricci and his companions focused on cozying up to the Confucians. On November 4, 1595, Ricci wrote to the Jesuit Father General Acquaviva: "I have noted down many terms and phrases [of the Chinese classics] in harmony with our faith, for instance, 'the unity of God,' 'the immortality of the soul,' the glory of the blessed,' and the like". Ricci intended to identify appropriate terms in the Confucian classics to give the Christian dogma a Mandarin dress and to illustrate his view that the Chinese had successfully safeguarded an extremely ancient knowledge of God. The portions of Ruggieri and Ricci's old "Buddhist" catechism dealing with God's revelation and requiring faith rather than reason were removed, while topics such as the "goodness of human nature" that appealed to Confucians were added. Ricci systematically substituted Buddhist terminology with phrases from the Chinese classics.... It was not a catechism in the traditional sense but a praeparatio evangelica: a way to entice the rationalist upper crust of Chinese society and to refute the "superstitious" and "foreign" forms of Chinese religion (such as Daoism and Buddhism) by logical argument while interpreting "original" Confucianism as a kind of Old Testament to Christianity. Ricci's "catechism" was thus not yet the Good News itself but a first step toward it. It argued that Chinese religion had once been thoroughly monotheistic and that this primeval monotheism had later degenerated through the influence of Daoism and Buddhism. In Ricci's view Christianity was nothing other than the fulfillment of China's Ur-monotheism.

-- The Birth of Orientalism, by Urs App

-- Noble lie 1 [Royal Lie] [Pious Fiction] [Pious Fraud] [Pious Invention], by Wikipedia

However, the thought of “what if?” is enough for someone to dream of a world where the famines imposed on Indians by the British, the Partition of India (which the United Nations Human Rights Council calls “the world’s largest mass migration”), and countless other atrocities could have been prevented had we been under Dara Shikoh’s unifying hand. Could the world have been in a much better place or was Aurganzeb’s ideology the only way forward?

The Trial of Dara Shikoh and The World of Islam

Dr. Ahmed’s play, The Trial of Dara Shikoh opens with Dara Shikoh on trial for apostasy, an allegation leveled at him by Aurangzeb. Dara Shikoh chooses to represent himself and testify. In addition, there are two other witnesses, a Hindu scholar named Gopi Lal, and a Sikh religious leader named Bahadur Singh. Both witnesses attest to Dara Shikoh’s work in creating religious unity which is unfortunately used against him by prosecutor Abdullah Khan. Khan argues that Dara Shikoh’s work with these scholars and belief that all religions are somehow intertwined is blasphemous and deserving of the highest sentence: the death penalty. One major example that Khan uses to argue his case is a ring that Dara Shikoh wears. On one side of the ring, the inscription reads, “Allah,” while the other side reads, “Prabhu,” the Sanskrit word for God. Dara Shikoh says “the two universes are encompassed and counterpoised in harmony on one small ring. For me, the concept provides a visual representation in its continuum of the essence of our spiritual unity (Ahmed).” Prosecutor Khan calls this show of unity to be blasphemous, claiming that this is proof of Dara Shikoh wandering away, “from the straight path of Islam (Ahmed).” So how does any of this tie in with Dr. Ahmed’s teachings in The World Of Islam?

The World Of Islam is a very popular course at American University for undergraduate students wishing to select the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) as a regional focus or students of International Service. Dr. Ahmed started with a discussion on early Islam and some theological concepts. We then proceeded to discuss the Golden Age of Islam, the colonial and the post-colonial identity, eventually leading to modern conflicts with and within the Muslim world.

Dr. Ahmed has a way of planning a brighter future by looking at the successes of the past. A major discussion we had in class was on the Caliphate of Córdoba when the Umayyad Dynasty established its presence in Andalusia. Dr. Ahmed explained how this was the golden age of Islam where religious and ethnic diversity not only thrived but was encouraged by the Caliphate and many technological advancements happened, some of which we still use today. Dr. Ahmed compared Córdoba to The United States, asking the class whether we currently live in the new Andalusia. Additionally, Dr. Ahmed also tried to dispel stereotypes of Muslims by telling us key concepts, principles, and events in the Holy Quran. For example, we discussed inclusivity in Islam by talking about Bilal Ibn Rabah, an Abyssian slave freed by Prophet Muhammed (peace be upon him). Bilal, who became a companion of the Prophet of Islam, was the first person to give the Muslim call to prayer, also known as Azan (or Adhan). Additionally, we discussed key figures like Khadija, the first wife of Prophet Muhammed (peace be upon him). Khadija was the first Muslim, proving that women have an integral place in Islam. We were also taught about Aisha, the youngest and revered wife of Prophet Muhammed (peace be upon him), who led troops into war! Yes, female Muslim general in the 7th century!

Greatest of all Dr. Ahmed taught us about how Islam is not about divisions or about fighting, it is about peace and harmony. Dara Shikoh’s ideals were the exact same, finding peace and harmony. The Trial Of Dara Shikoh could be considered a way to not only help understand the past but also to understand our present. There are very clearly individuals in the Muslim world that believe Aurangzeb’s orthodox ideology is the best way forward, and similarly, there are people who wished they could have seen Dara Shikoh’s views come to fruition. Both sides remain at odds with each other as Muslims work to understand their place in the world despite the challenges of conflict, globalization, and Islamophobia.

Dara Shikoh and Me

When I was growing up, my maternal grandmother would come to the United States from India to take care of me while my mother worked. I have so many fond memories of spending time with her, but some of my most fond memories were spent learning about her time growing up in an undivided India. Unfortunately, those stories also came with horrifying recounts of the partition. Both my grandparents were born in what is now Pakistan, 75 years after the end of British colonization. My grandmother, Shakuntala, was born a daughter of a Sikh ophthalmologist, Rai Bahadur Aroor Singh Chawala, and a Hindu lady, Kesar Devi in Daska, a town in Punjab. Already, my family had created a bond across religious tensions, one that resulted in eight brothers and sisters.

My maternal grandfather was born to landowners Gopal Singh and Veeranwali Saluja in Jhelum, Punjab. The story of my grandfather, while very interesting, doesn’t quite involve the partition, as his family had moved to Jaipur, Rajasthan, long before. However, my grandmother and her family ended up having to escape to India. She told me that there was never any “formal announcement,”; it just came through the grapevine that the partition was happening and everyone needed to go to their respective side. Initially, my great-grandfather was apprehensive to leave but after hearing of the atrocities that occurred, he purchased a rifle and poison. He had instructed all the women of the house that if anyone attempted to come in and cause harm that they were all to line up against the wall where they would be shot one by one and if they survived, poison was plan B. It was their Muslim neighbors who helped my half-Sikh and half-Hindu family escape. After hours of sitting in a tiny military jeep with at least 3 other families packed like sardines, they arrived at a refugee camp across the newly created border with nothing but the clothes on their backs. Their lives as they knew them, were forever gone. My grandmother talked about how her mother left milk boiling on the stove before they ran out of their home. From this refugee camp in Amritsar, just past the famed Wagah Border, they were then displaced again to Jalander, Punjab where they worked to rebuild their lives.

My mother, Rima was born in New Delhi and soon thereafter my grandfather got a job offer in Patiala, Punjab. So their family of three moved. My mother ended up attending Yadavindra Public School, the sister school of Aitchison College, Lahore. Growing up, my mother taught me exactly what my grandparents taught her: all religions believe in peace and unity, and all faiths deserve equal respect.

Despite the hardship my grandmother’s family went through, she recognized that it was a mutual respect for one another despite religion that not only created her family but allowed her to escape the atrocities of the Partition. My grandfather, a lawyer by profession, worked on cases for women’s rights and religious discrimination hoping that the wounds of the Partition would eventually heal. However, religious tensions only got worse with the Indo-Pak wars and the 1984 riots against Sikhs following the death of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

Growing up and learning this history of my family, all I could think of is how different my life would have been if my family’s history was rooted in intolerance. I probably would not have been here today. For centuries, inter-religious unity (or at the very least tolerance) existed in India and led to such amazing achievements. The great Mughal empire, of which Dara Shikoh was named heir apparent, was a blend of Persian, Central Asian, and Indian cultures. This can be seen in Shah Jehan’s Taj Mahal.

On the other hand, Aurangzeb deepened religious tensions which I believe eventually led to the almost irreconcilable frictions that caused the partition. Could Dara Shikoh have prevented the Partition? I can’t definitively answer that question but, unity would have made it harder for India to fall into the hands of the British Empire.

I did not learn about Dara Shikoh until I was in Dr. Ahmed’s class, and I believe that it is a disservice to the world for us not to have to learn about him earlier. There are so many stories across the world, just like mine, of families created and surviving thanks to unity across perceived “enemy” lines. I’m sure every South Asian, whether they are Pakistani, Indian, Nepalese, Sri Lankan, or Bangladeshi, can attest to this. Time and time again, history has taught us that unity maintains culture while those who are divided fall. The British took advantage of this with their “divide and rule” policy. I’m sure Aurangzeb was not all bad, he did help the empire to flourish. He also did not ever use state funds for himself, instead making skull caps and shoes to earn a living.

Dr. Ahmed told us that later writings by Aurangzeb show that he regretted executing his brother and imprisoning his father. It still does not stop me from thinking “what if.” I try to honor my family’s legacy by learning about the past and present conflicts between religious communities in South Asia and hope that I can one day see peace between its nations. Recently, I started a fundraiser at American University for flood relief in Pakistan. I feel like even small gestures of kindness can have a profound impact. They can even help start the process of healing deep wounds. Beyond asking, “What if?” Dara Shikoh’s story and Dr. Ahmed’s teachings stand as a reminder that if those in the past could envision a future of peace and unity, we should never stop fighting for those values today.