III. The Sixth Discourse; on the Persians

by Sir William Jones

Delivered 10th February, 1789

-- III. The Sixth Discourse; on the Persians, by Sir William Jones, Delivered 10th February, 1789, from Asiatic Researches; or Transactions of the Society Instituted in Bengal For Inquiring Into the History and Antiquities, The Arts, Sciences, and Literature of Asia, Volume II, 1788 P. 36-53

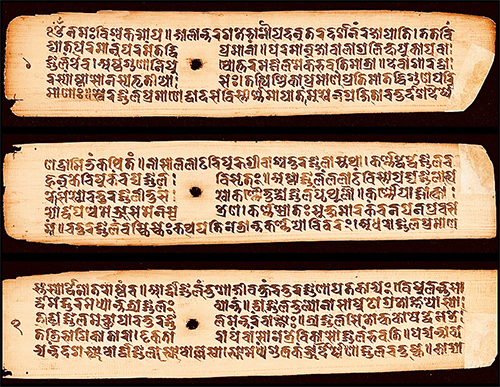

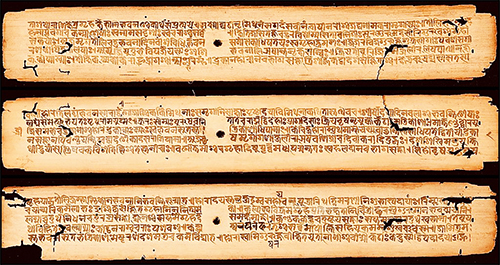

-- ZEND-AVESTA, WORK OF ZOROASTRE, Containing the Theological, Physical & Moral Ideas of this Legislator, the Ceremonies of the Religious Worship he established, & several important features relating to the ancient History of the Persians: Translated into French on the Original Zend, with Notes; & accompanied by several Treatises specific to clarifying the Matters who are subject to it. By M. ANQUETIL DU PERRON, of the Royal Academy of Inscriptions & Belles-Lettres, & Interpreter of the King for Oriental Languages. FIRST VOLUME. SECOND PART, Which includes the Vendidad Sade (i.e. I'zeschnè, the Vispered & the VENDIDAD itself), preceded by the Notices of the Zend Manuscripts, Pehlvis, Persians & Indians, deposited by the Translator in the Library of King; Titles & Summaries of Articles & c. both. Volumes of this Work; & of the VIE DE ZOROASTRE: With a plate engraved in intaglio. 1771

-- Oupnek'hat [Four Upanishads], by Anquetil Duperron. 1802

Gentlemen,

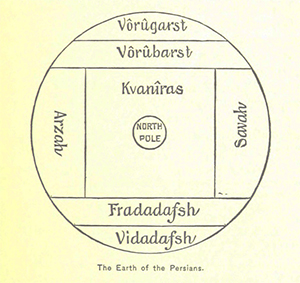

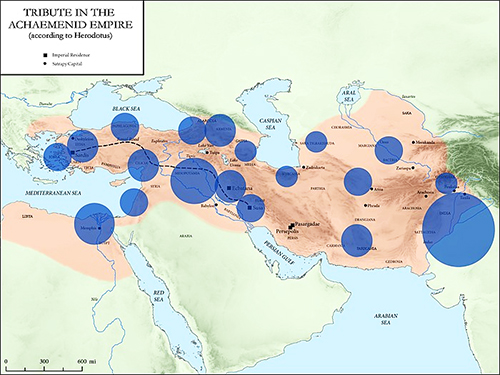

I turn with delight from the vast mountains and barren deserts of Turan over which we travelled last year with no perfect knowledge of our course, and request you now to accompany me on a literary journey through one of the most celebrated and most beautiful countries in the world; a country, the history and languages of which, both ancient and modern, I have long attentively studied, and on which I may without arrogance promise you more positive information, than I could possibly procure on a nation so disunited and so unlettered as the Tartars: I mean that, which Europeans improperly call Persia, the name of a single province being applied to the whole Empire of Iran, as it is correctly denominated by the present natives of it, and by all the learned Muselmans, who reside in these British territories. To give you an idea of its largest boundaries, agreeably to my former mode of describing India, Arabia, and Tartary, between which it lies, let us begin with the source of the great Assyrian stream, Euphrates, (as the Greeks, according to their custom, were pleased to miscall the Forat) and thence descend to its mouth in the Green Sea, or Persian Gulf, including in our line some considerable districts and towns on both sides of the river; then, coasting Persia, properly so named, and other Iranian provinces, we come to the delta of the Sindhu or Indus; whence ascending to the mountains of Cashghar, we discover its fountains and those of the Jaihun, down which we are conducted to the Caspian, which formerly perhaps it entered, though it lose itself now in the sands and lakes of Khwarezm: we next are led from the sea of Khozar, by the banks of the Cur, or Cyrus, and along the Caucasean ridges, to the shore of the Euxine, and thence, by the several Greecian seas, to the point, whence we took our departure, at no considerable distance from the Mediterranean. We cannot but include the lower Asia within this outline, because it was unquestionably a part of the Persian, if not of the old Assyrian, Empire; for we know, that it was under the dominion of CAIKHOSRAU; and DIODORUS, we find, asserts, that the kingdom of Troas was dependent on Assyria, since PRIAM implored and obtained succours from his Emperor TEUTAMES, whose name approaches nearer to TAHMURAS, than to that of any other Assyrian monarch. Thus may we look on Iran as the noblest Island, (for so the Greeks and the Arabs would have called it), or at least as the noblest peninsula, on this habitable globe; and if M. BAILLY had fixed on it as the Atlantis of PLATO, he might have supported his opinion with far stronger arguments than any, that he has adduced in favour of New Zembla: if the account, indeed, of the Atlantes be not purely an Egyptian, or an Utopian, fable, I should be more inclined to place them in Iran than in any region, with which I am acquainted.

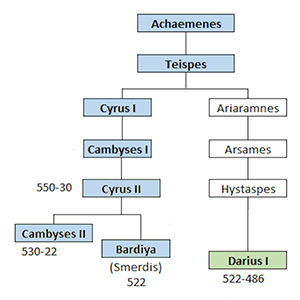

It may seem strange, that the ancient history of so distinguished an Empire should be yet so imperfectly known; but very satisfactory reasons may be assigned for our ignorance of it: the principal of them are the superficial knowledge of the Greeks and Jews, and the loss of Persian archives or historical compositions. That the Greecian writters, before XENOPHON [430 BC-355 BC], had no acquaintance with Persia, and that all their accounts of it are wholly fabulous, is a paradox too extravagant to be seriously maintained; but their connection with it in war or peace had, indeed, been generally confined to bordering kingdoms under feudatory princes; and the first Persian Emperor, whose life and character they seem to have known with tolerable accuracy, was the great CYRUS, whom I call, without fear of contradiction, CAIKHOSRAU; for I shall then only doubt that the KHOSRAU of FIRDAUSI was the CYRUS of the first Greek historian, and the Hero of the oldest political and moral romance, when I doubt that LOUIS Quatorze and LEWIS the Fourteenth were one and the same French King: it is utterly incredible, that two different princes of Persia should each have been born in a foreign and hostile territory; should each have been doomed to death in his infancy by his maternal grandfather in consequence of portentous dreams, real or invented; should each have been saved by the remorse of his destined murderer, and should each, after a similar education among herdsmen as the son of a herdsman, have found means to revisit his paternal kingdom, and having delivered it, after a long and triumphant war, from the tyrant, who had invaded it, should have restored it to the summit of power and magnificence. Whether so romantic a story, which is the subject of an Epic Poem, as majestic and entire as the Iliad, be historically true, we may feel perhaps an inclination to doubt; but it cannot with reason be denied, that the outline of it related to a single Hero, whom the Asiatics, conversing with the father of European history, described according to their popular traditions by his true name, which the Greek alphabet could not express: nor will a difference of names affect the question; since the Greeks had little regard for truth, which they sacrificed willingly to the Graces of their language, and the nicety of their ears; and, if they could render foreign words melodious, they were never solicitous to make them exact; hence they probably formed CAMBYSES from CAMBAKHSH, or Granting desires, a title rather than a name, and XERXES from SHIRUYI, a Prince and warrior in the Shahnama, or from SHIRAHAH, which might also have been a title; for the Asiatic Princes have constantly assumed new titles or epithets at different periods of their lives, or on different occasions; a custom, which we have seen prevalent in our own times both in Iran and Hindustan, and which has been a source of great confusion even in the scriptural accounts of Babylonian occurrences: both Greeks and Jews have in fact accommodated Persian names to their own articulation; and both seem to have disregarded the native literature of Iran, without which they could at most attain a general and imperfect knowledge of the country. As to the Persians themselves, who were contemporary with the Jews and Greeks, they must have been acquainted with the history of their own times, and with the traditional accounts of past ages; but for a reason, which will presently appear, they chose to consider CAYUMERS as the founder of their empire; and, in the numerous distractions, which followed the overthrow of DARA, especially in the great revolution on the defeat of YEZDEGIRD, their civil histories were lost, as those of India have unhappily been, from the solicitude of the priests, the only depositaries of their learning, to preserve their books of law and religion at the expense of all others: hence it has happened, that nothing remains of genuine Persian history before the dynasty of SASAN [224-651], except a few rustic traditions and fables, which furnished materials for the Shahnamah, and which are still supposed to exist in the Pahlavi language.

Dara I or Darab I was the penultimate king of the mythological Kayanian dynasty, ruling for 12 years. He was the son of Kay Bahman. Most accounts agree that Dara's mother was Humay Chehrzad, who had married her father, Kay Bahman. After Kay Bahman's death, Humay, who was pregnant with Dara, became the regent of the realm. Humay later hid the news of Dara's birth, and abandoned him on casket filled with expensive jewels on a river. The river has reported to have been the Euphrates, the Tigris, the Kor river in Fars, the Polvar river in Fars, or the Balkh river.

When Dara became older he eventually found his way back to Humay, who abdicated in his favor. Dara I was later succeeded by his son Dara II.

Dara I has been credited with the establishment of the Persian postal system, which is a reflection of [???] the introduction or restructuring of the postal system by the Achaemenid King of Kings, Darius I the Great (r. 522–486 BC). The last Kayanian kings were usually connected with western Iran, as demonstrated by reports of Dara I using Babylon as his residence. Most sources credit Dara I with the foundation of the city of Darabgerd in Fars, while a few consider Dara II to have been its founder.

According to later sources, Dara I had a son named Firuzshah [!!!], whose achievements are mentioned in the Firuz-nameh by Haji Muhammad Bigami.

-- Dara I, by Wikipedia

DĀRĀ(B) (1)

Dārā(b) I was the son of the Kayanid Bahman Ardašīr. According to most of the sources, his mother was Homā Čehrāzād, who married her own father, Bahman (Šāh-nāma, Moscow, VI, p. 352; Ṭabarī, I, p. 687; Balʿamī, ed. Bahār, p. 687; Masʿūdī, Morūj, ed. Pellat, I, p. 272; Ṯaʿālebī, Ḡorar, p. 389; Meskawayh, p. 34; Gardīzī, ed. Ḥabībī, p. 15; Ṭarsūsī, pp. 10-11). In one tradition, however, this marriage was denied, and it was maintained that Homā died a virgin (Ebn al-Balḵī, p. 54). Nevertheless, the former version, which accords with the old Iranian tradition of next-of-kin marriage, is certainly authentic. According to this legend, Bahman died before Dārā was born and appointed Homā his regent. When Dārā was born she did not reveal the news of his birth but had him laid, together with precious jewels, in a casket and exposed on the river Euphrates (Šāh-nāma, Moscow, VI, p. 356; Ṭarsūsī, p. 11), the Tigris (Maqdesī, Badʾ III, p. 150), the Kor river in Fārs (Ṭabarī, I, p. 689), the Eṣṭaḵr (i.e., Polvār) river in Fārs (Ṯaʿālebī, Ḡorar, p. 392), or the Balḵ river (Ṭabarī, I, p. 690). The child was found by a fuller (Šāh-nāma, Moscow, VI, p. 356; Ṯaʿālebī, Ḡorar, p. 392; Mojmal, ed. Bahār, p. 54; Maqdesī, Badʾ III, p. 150; Ṭarsūsī, where his name is given as Hormaz) or a miller (Ṭabarī, I, p. 690; Balʿamī, ed. Bahār, p. 690), who called him Dārāb, because he was found in the water (āb) among the trees (dār;itfoṮaʿālebī, Ḡorar, p. 394; Šāh-nāma, Moscow, VI, p. 358; Ṭarsūsī, pp. 13-14; Balʿamī, ed. Bahār, p. 690: dār “hold, take”).

This story seems to be based on popular etymology. A similar etiological legend is told about Kawād, the founder of the Kayanid dynasty (Bundahišn, TD2, p. 231; Christensen, 1931, pp. 70-71; idem, 1933-35; Bailey, pp. 69 ff.). It belongs to a type of legend “which is generally associated with the change of dynasties, the end of an era, or a major shift of power” (Yarshater, p. 522; cf. Christensen, 1933-35). In spite of the discontent of his foster-father, who wanted the boy to become a fuller, Dārā, eager to receive an aristocratic education, was first handed over to scholars, who taught him the Avesta and its commentary (Zand o Estā); then he was trained in archery, horsemanship, polo, and similar skills. Dārā, who doubted his relationship to the fuller and was curious to find out his true origin, compelled the fuller’s wife to reveal his descent. As he was ambitious to reach high positions, Dārā entered the service of Rašnavād, Homā’s commander-in-chief (Šāh-nāma, Moscow, VI, pp. 358 ff.; Ṯaʿālebī, Ḡorar, pp. 394 ff.; Maqdesī, Badʾ III, p. 150; Balʿamī, ed. Bahār, pp. 690-91; Ṭarsūsī, pp. 27 ff., with different details). Eventually Dārā was introduced to the queen, who after a reign of thirty years (thirty-two according to Šāh-nāma, Moscow, VI, p. 371 v. 312) abdicated in his favor.

Dārā reigned for twelve years (Bundahišn, TD2, p. 240; Ḥamza, p. 13; Mojmal, ed. Bahār, p. 55; Ebn al-Balḵī, p. 55; Dīnavarī, ed. Guirgass, p. 31; Masʿūdī, Morūj, ed. Pellat, I, p. 272). During his reign he fought with Šoʿayb, the Arab commander from the Qotayb tribe (Šāh-nāma, Moscow, VI, pp. 374-75; Ṭarsūsī, pp. 354-72). He also campaigned against Fīlfūs (Philip) of Rūm (i.e., Greece), who was defeated and compelled to pay tribute and agreed to marry his daughter Nāhīd (Šāh-nāma, Moscow, VI, p. 377; Ṭarsūsī, p. 380) or Halāy (Ṭabarī, I, p. 697) to Dārā. Although pregnant, she was soon sent back home because of her foul breath. In Rūm she bore Eskandar (Alexander; Šāh-nāma, Moscow, pp. 375 ff.; Dīnavarī, pp. 31-32; Ṯaʿālebī, Ḡorar, pp. 399 ff.; Ṭabarī, I, pp. 696-97; Mojmal, ed. Bahār, p. 54; Ṭarsūsī, pp. 390 ff.). This last episode represents an obvious attempt to provide a link between Alexander the Great and the Persian royal house by making him a half-brother of Dārā II (Yarshater, pp. 522-23).

The introduction of the Persian postal system was attributed to Dārā I (Ṭabarī, I, p. 692; Ḥamza, p. 39; Ṯaʿālebī, Ḡorar, p. 398; Gardīzī, ed. Ḥabībī, p. 16), apparently reflecting a historical fact: the introduction or reorganization of the postal system by Darius I the Great. The foundation of the city of Dārābgerd in Fārs was attributed to him in most of the sources (Ḥamza, p. 39; Ṭabarī, I, p. 692; Balʿamī, ed. Bahār, p. 692; Ebn al-Balḵī, p. 55; Ṯaʿālebī, Ḡorar, p. 398; Gardīzī, ed. Ḥabībī, p. 16; Mojmal, ed. Bahār, p. 55; Ebn al-Balḵī, p. 55; Ṭarsūsī, pp. 353, 452; see Dārāb ii), though in some others Dārā II was credited with its foundation (Pahlavi Texts, ed. Jamasp-Asana, p. 22; Tārīḵ-e gozīda, ed. Browne, p. 99). Babylon was mentioned as his residence (Ṭabarī, I, p. 692; Masʿūdī, Morūj, ed. Pellat, I, p. 272), which shows the general tendency in the tradition to link the exploits of the last Kayanid kings with western Iran.

Dārā was supposed, according to the late sources, to have had a son called Fīrūzšāh, whose exploits are related in the popular Persian romance Fīrūzšāh-nāma, published under the title Dārāb-nāma by Ḥājī Moḥammad Bīḡamī (ed. Ḏ. Ṣafā, Tehran, 1339-41 Š./1960-62).

-- DĀRĀ(B) (1), by Encyclopedia Iranica

The annals of the Pishdadi, or Assyrian, race must be considered as dark and fabulous; and those of the Cayani family, or the Medes and Persians, as heroic and poetical; though the lunar eclipses, said to be mentioned by PTOLEMY, fix the time of GUSHTASP, the prince, by whom ZERATUSHT was protected: of the Parthian kings descended from ARSHAC or ARSACES, we know little more than the names; but the Sasani's had so long an intercourse with the Emperors of Rome and Byzantium, that the period of their dominion may be called an historical age. In attempting to ascertain the beginning of the Assyrian empire, we are deluded, as in a thousand instances, by names arbitrarily imposed: it had been settled by chronologers, that the first monarchy established in Persia was the Assyrian; and NEWTON, finding some of opinion, that it rose in the first century after the Flood, but unable by his own calculations to extend it farther back than seven hundred and ninety years before CHRIST, rejected part of the old system and adopted the rest of it; concluding, that the Assyrian Monarchs began to reign about two hundred years after SOLOMON, and that, in all preceding ages, the government of Iran had been divided into several petty states and principalities. Of this opinion I confess myself to have been; when, disregarding the wild chronology of the Muselmans and Gabrs, I had allowed the utmost natural duration to the reigns of eleven Pishdadi kings, without being able to add more than a hundred years to NEWTON'S computation. It seemed, indeed, unaccountably strange, that, although ABRAHAM had found a regular monarchy in Egypt, although the kingdom of Yemen had just pretensions to very high antiquity, although the Chinese, in the twelfth century before our era, had made approaches at least to the present form of their extensive dominion, and although we can hardly suppose the first Indian monarchs to have reigned less than three thousand years ago, yet Persia, the most delightful, the most compact, the most desirable country of them all, should have remained for so many ages unsettled and disunited. A fortunate discovery, for which I was first indebted to Mir MUHAMMED HUSAIN, one of the most intelligent Muselmans in India, has at once dissipated the cloud, and cast a gleam of light on the primeval history of Iran and of the human race, of which I had long despaired, and which could hardly have dawned from any other quarter.

Authorship

Several manuscripts have been discovered that identifies the author as Mīr Du'lfiqar Ardestānī (also known as Mollah Mowbad). Mir Du'lfiqar is now generally accepted as the author of this work.

Before these manuscripts were discovered, however, Sir William Jones identified the author as Mohsin Fani Kashmiri. In 1856, a Parsi named Keykosrow b. Kāvūs claimed Khosrow Esfandiyar as the author, who was son of Azar Kayvan.

-- Dabestan-e Mazaheb, by Wikipedia, by Wikipedia

Three different men have been identified as the author of Dābestān-e maḏāheb. In 1789 William Jones proposed Moḥsen Fānī Kašmīrī (d. 1081/1670), but subsequently Captain Vans Kennedy and William Erskine both independently rejected this identification. An entirely conjectural attribution to Āḏar Kayvān’s son and spiritual successor Keyḵosrow Esfandīār was put forth in 1856 by an Indian Parsi, Keyḵosrow b. Kāvūs, and this suggestion has been reiterated by Raḥīm Reżāzāda Malek, editor of the most recent edition (see below; II, pp. 58-67, quoted from Cama Oriental Institute, Bombay, ms. 300). Some historians and authors of biographical dictionaries, including Ṣamṣām-al-Dawla Šāhnavāz Khan (I, pp. 226-27; II, pp. 76, 392), Serāj-al-Dīn ʿAlī Khan Ārezū (Rieu, Persian Manuscripts II, p. 1081), Āzād Belgrāmī (p. 22), and Raḥm-ʿAlī Khan Īmān (p. 179) identified the author as Mīr Ḏu’l-feqār Ardestānī (ca. 1026-81/1617-70), better known under his pen name Mollā Mowbad or Mowbadšāh, and this attribution is now generally accepted. [???!!!]

-- Dabestan-E Madaheb, by Encyclopedia Iranica

The rare and interesting tract on twelve different religions, entitled the Dabistan, and composed by a Mohammedan traveller, a native of Cashmir, named MOHSAN, but distinguished by the assumed surname of FANI, or Perishable, begins with a wonderfully curious chapter on the religion of HUSHANG, which was long anterior to that of ZERATUSHT, but had continued to be secretly professed by many learned Persians even to the author's time; and several of the most eminent of them, dissenting in many points from the Gabrs, and persecuted by the ruling powers of their country, had retired to India; where they compiled a number of books, now extremely scarce, which MOHSAN had perused, and with the writers of which, or with many of them, he had contracted an intimate friendship: from them he learned, that a powerful monarchy had been established for ages in Iran before the accession of CAYUMERS, that it was called the Mahabadian dynasty for a reason, which will soon be mentioned, and that many princes, of whom seven or eight only are named in the Dabistan, and among them MAHBUL, or MAHA BELI, had raised their empire to the zenith of human glory. If we can rely on this evidence, which to me appears unexceptionable, the Iranian monarchy must have been the oldest in the world; but it will remain dubious, to which of the three stocks, Hindu, Arabian, or Tartar, the first Kings of Iran belonged, or whether they sprang from a fourth race distinct from any of the others; and these are questions, which we shall be able, I imagine, to answer precisely, when we have carefully inquired into the languages and letters, religion and philosophy, and incidentally into the arts and sciences, of the ancient Persians.

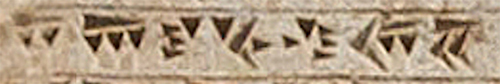

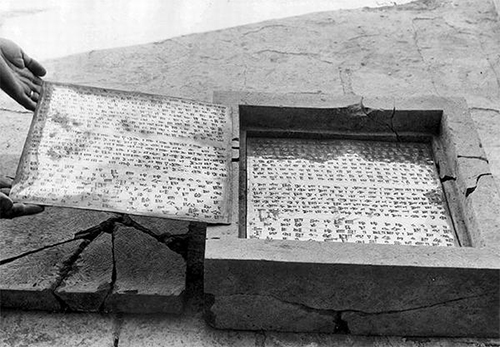

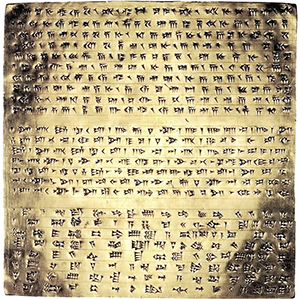

I. In the new and important remarks, which I am going to offer, on the ancient languages and characters of Iran, I am sensible, that you must give me credit for many assertions, which on this occasion it is impossible to prove; for I should ill deserve your indulgent attention, if I were to abuse it by repeating a dry list of detached words, and presenting you with a vocabulary instead of a dissertation; but, since I have no system to maintain, and have not suffered imagination to delude my judgement; since I have habituated myself to form opinions of men and things from evidence, which is the only solid basis of civil, as experiment is of natural knowledge; and since I have maturely considered the questions which I mean to discuss; you will not, I am persuaded, suspect my testimony, or think that I go too far, when I assure you, that I will assert nothing positively, which I am not able satisfactorily to demonstrate. When MUHAMMED was born, and ANUSHIRAVAN, whom he calls the Just King, sat on the throne of Persia, two languages appear to have been generally prevalent in the great empire of Iran; that of the Court, thence named Deri, which was only a refined and elegant dialect of the Parsi, so called from the province of which Shiraz is now the capital, and that of the learned, in which most books were composed, and which had the name of Pahlavi, either from the heroes, who spoke it in former times, or from Pahlu, a tract of land, which included, we are told, some considerable cities of Irak: the ruder dialects of both were, and, I believe, still are, spoken by the rustics in several provinces; and in many of them, as Herdt, Zabul, Sistan and others, distinct idioms were vernacular, as it happens in every kingdom of great extent. "Besides the Parsi and Pahlavi, a very ancient and abstruse tongue was known to the priests and philosophers, called the language of the Zend, because a book on religious and moral duties, which they held sacred, and which bore that name, had been written in it; while the Pazend, or comment on that work, was composed in Pahlavi, as a more popular idiom; but a learned follower of ZERATUSHT, named BAHMAN, who lately died at Calcutta, where he had lived with me as a Persian reader about three years, assured me, that the letters of his prophet's book were properly called Zend, and the language, Avesta, as the words of the Veda's are Sanscrit, and the characters, Nagari; or as the old Saga's and poems of Iceland were expressed in Runic letters: let us however, in compliance with custom, give the name of Zend to the sacred language of Persia, until we can find, as we shall very soon, a fitter appellation for it. The Zend and the old Pahlavi are almost extinct in Iran; for among six or seven thousand Gabrs, who reside chiefly at Yezd, and in Cirman, there are very few, who can read Pahlavi, and scarce any, who even boast of knowing the Zend; while the Parsi, which remains almost pure in the Shahnamah, has now become by the Intermixture of numberless Arabic words, and many imperceptible changes, a new language exquisitely polished by a series of fine writers in prose and verse, and analogous to the different idioms gradually formed in Europe after the subversion of the Roman empire: but with modern Persian we have no concern in our present inquiry, which I confine to the ages, that preceded the Mohammedan conquest. Having twice read the works of FIRDAUSI with great attention, since I applied myself to the study of old Indian literature, I can assure you with confidence, that hundreds of Parsi nouns are pure Sanscrit, with no other change than such as may be observed in the numerous bhasha's, or vernacular dialects, of India; that very many Persian imperatives are the roots of Sanscrit verbs; and that even the moods and tenses of the Persian verb substantive, which is the model of all the rest, are deducible from the Sanscrit by an easy and clear analogy: we may hence conclude, that the Parsi was derived, like the various Indian dialects, from the language of the Brahmans; and I must add, that in the pure Persian I find no trace of any Arabian tongue, except what proceeded from the known intercourse between the Persians and Arabs, especially in the time of BAHRAM, who was educated in Arabia, and whose Arabic verses are still extant, together with his heroic line in Deri, which many suppose to be the first attempt at Persian versification in Arabian metre: but, without having recourse to other arguments, the composition of words, in which the genious of the Persian delights, and which that of the Arabic abhors, is a decisive proof, that the Parsi sprang from an Indian, and not from an Arabian, stock. Considering languages as mere instruments of knowledge, and having strong reasons to doubt the existence of genuine books in Zend or Pahlavi (especially since the well-informed author of the Dabistan affirms the work of ZERATUSHT to have been lost, and its place supplied by a recent compilation) I had no inducement, though I had an opportunity, to learn what remains of those ancient languages; but I often conversed on them with my friend BAHMAN, and both of us were convinced after full consideration, that the Zend bore a strong resemblance to Sanscrit, and the Pahlavi to Arabic. He had at my request translated into Pahlavi the fine inscription, exhibited in the Gulistan, on the diadem of CYRUS; and I had the patience to read the list of words from the Pazend in the appendix to the Farhangi Jehangiri: this examination gave me perfect conviction, that the Pahlavi was a dialect of the Chaldaic; and of this curious fact I will exhibit a short proof. By the nature of the Chaldean tongue most words ended in the first long vowel like shemia, heaven; and that very word, unaltered in a single letter, we find in the Pazend, together with lailia, night, meya, water, nira, fire, matra, rain, and a multitude of others, all Arabic or Hebrew with a Chaldean termination: so zamar, by a beautiful metaphor from pruning trees, means in Hebrew to compose verses, and thence, by an easy transition, to sing, them; and in Pahlavi we see the verb zamruniten, to sing, with its forms zamrunemi, I sing, and zamrunid, he sang; the verbal terminations of the Persian being added to the Chaldaic root. Now all those words are integral parts of the language, not adventitious to it like the Arabic nouns and verbals engrafted on modern Persian; and this distinction convinces me, that the dialect of the Gabrs, which they pretend to be that of ZERATUSHT, and of which BAHMAN gave me a variety of written specimens, is a late invention of their priests, or subsequent at least to the Muselman invasion; for, although it may be possible, that a few of their sacred books were preserved, as he used to assert, in sheets of lead or copper at the bottom of wells near Yezd, yet as the conquerors had not only a spiritual, but a political, interest in persecuting a warlike, robust, and indignant race of irreconcilable conquered subjects, a long time must have elapsed, before the hidden scriptures could have been safely brought to light, and few, who could perfectly understand them, must then have remained; but, as they continued to profess among themselves the religion of their forefathers, it became expedient for the Mubeds to supply the lost or mutilated works of their legislator by new compositions, partly from their imperfect recollection, and partly from such moral and religious knowledge, as they gleaned, most probably, among the Christians, with whom they had an intercourse. One rule we may fairly establish in deciding the question, whether the books of the modern Gabrs were anterior to the invasion of the Arabs: when an Arabic noun occurs in them changed only by the spirit of the Chaldean idiom, as werta, for werd, a rose, daba, for dhahab, gold, or deman, for zeman, time, we may allow it to have been ancient Pahlavi; but, when we meet with verbal nouns or infinitives, evidently formed by the rules of Arabian grammar, we may be sure, that the phrases, in which they occur, are comparatively modern; and not a single passage, which BAHMAN produced from the books of his religion, would abide this test.

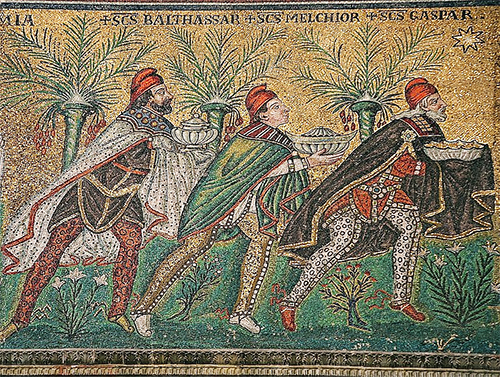

We come now to the language of the Zend, and here I must impart a discovery, which I lately made, and from which we may draw the most interesting consequences. M. ANQUETIL, who had the merit of undertaking a voyage to India, in his earliest youth, with no other view than to recover the writings of ZERATUSHT, and who would have acquired a brilliant reputation in France, if he had not sullied it by his immoderate vanity and virulence of temper, which alienated the good will even of his own countrymen, has exhibited in his work, entitled Zendavesta, two vocabularies in Zend and Pahlavi, which he had found in an approved collection of Rawayat, or Traditional Pieces, in modern Persian: of his Pahlavi no more needs be said, than that it strongly confirms my opinion concerning the Chaldaic origin of that language; but, when I perused the Zend glossary, I was inexpressibly surprised to find, that six or seven words in ten were pure Sanscrit, and even some of their inflexions formed by the rules of the Vyacaran; as yushmacam, the genitive plural of yushmad. Now M. ANQUETIL most certainly, and the Persian compiler most probably, had no knowledge of Sanscrit; and could not, therefore, have invented a list of Sanscrit words: it is, therefore, an authentic list of Zena words, which had been preserved in books or by tradition; and it follows, that the language of the Zend was at least a dialect of the Sanscrit, approaching perhaps as nearly to it as the Pracrit, or other popular idioms, which we know to have been spoken in India two thousand years ago. From all these facts it is a necessary consequence, that the oldest discoverable languages of Persia were Chaldaic and Sanscrit; and that, when they had ceased to be vernacular, the Pahlavi and Zend were deduced from them respectively, and the Parsi either from the Zend, or immediately from the dialect of the Brahmans; but all had perhaps a mixture of Tartarain; for the best lexicographers assert, that numberless words in ancient Persian are taken from the language of the Cimmerians, or the Tartars of Kipchak; so that the three families, whose lineage we have examined in former discourses, had left visible traces of themselves in Iran, long before the Tartars and Arabs had rushed from their deserts, and returned to that very country, from which in all probability they originally proceeded, and which the Hindus had abandoned in an earlier age, with positive commands from their legislators to revisit it no more. [???] I close this head with observing, that no supposition of a mere political or commercial intercourse between the different nations will account for the Sanscrit and Chaldaic words, which we find in the old Persian tongues; because they are, in the first place, too numerous to have been introduced by such means, and, secondly, are not the names of exotic animals, commodities, or arts, but those of material elements, parts of the body, natural objects and relations, affections of the mind, and other ideas common to the whole race of man.

Jamshid, also known as Yima, is the fourth Shah of the mythological Pishdadian dynasty of Iran according to Shahnameh.

In Persian mythology and folklore, Jamshid is described as the fourth and greatest king of the epigraphically unattested Pishdadian Dynasty (before the Kayanian dynasty). This role is already alluded to in Zoroastrian scripture (e.g. Yasht 19, Vendidad 2), where the figure appears as Yima [x], "radiant Yima", from which the name 'Jamshid' is derived.

Both Jam and Jamshid remain common Iranian and Zoroastrian male names that are also popular in surrounding areas of Iran such as Afghanistan and Tajikistan. Edward FitzGerald transliterated the name as Jamshyd. In the eastern regions of Greater Iran, and by the Zoroastrians of the Indian subcontinent it is rendered as Jamshed based on the Classical Persian pronunciation.

-- Jamshid, by Wikipedia

The Kayanians are a legendary dynasty of Persian/Iranian tradition and folklore which supposedly ruled after the Pishdadians each of whom held the title Kay (such as Kay Khosrow), meaning "king". Considered collectively, the Kayanian kings are the heroes of the Avesta, the sacred texts of Zoroastrianism, and of the Shahnameh, the national epic of Greater Iran.

As an epithet of kings and the reason the dynasty is so called, Middle [x] and New Persian kay(an) originates from Avestan [x] kavi (or kauui) "king" and also "poet-sacrificer" or "poet-priest". Kavi may have originally signified an insightful fashioner in Proto-Indo-Iranian, which later acquired a poetic aspect in Indic and warrior and royal connotation in Iranian.In·dic: 1. Of or relating to India or its peoples or cultures. 2. Of or relating to the branch of the Indo-European language family comprising Sanskrit, the Prakrits, and their modern descendants, such as Bengali, Hindi-Urdu, and Punjabi. n. The Indic branch of Indo-European. Also called Indo-Aryan.

-- Indic, by The Free Dictionary

The word is also etymologically related to the Avestan notion of kavaēm kharēno, the "divine royal glory" that the Kayanian kings were said to hold. The Kiani Crown is a physical manifestation of that belief.

In Zoroastrianism

The earliest known foreshadowing of the major legends of the Kayanian kings appears in the Yashts of the Avesta, where the dynasts offer sacrifices to the god Ahura Mazda in order to earn their support and to gain strength in the perpetual struggle against their enemies, the Anaryas (non-Aryans, sometimes identified as the Turanians).

In Yasht 5, 9.25, 17.45-46, Haosravah, a Kayanian king later known as Kay Khosrow, together with Zoroaster and Jamasp (a premier of Zoroaster's patron Vishtaspa, another Kayanian king) worship in Airyanem Vaejah. The account tells that King Haosravah united the various Aryan (Iranian) tribes into one nation (Yasht 5.49, 9.21, 15.32, 17.41).

In Mandaeism

In Mandaeism, Book 18 of the Right Ginza lists several Kayanian kings, namely Kay Kawad, Kay Kavus (Uzava), Kay Khosrow, Kay Lohrasp, and Vishtaspa.

Sassanid legend

Towards the end of the Sassanid period, Khosrow I (named after the Kay Khosrow of legend) ordered a compilation of the legends surrounding the Kayanians. The result was the Khwaday-Namag or "Book of Lords", a long historiography of the Iranian nation [???] from the primordial Gayomart to the reign of Khosrow II, with events arranged according to the perceived sequence of kings and queens, fifty in number.historiography: the writing of history, especially the writing of history based on the critical examination of sources, the selection of particular details from the authentic materials in those sources, and the synthesis of those details into a narrative that stands the test of critical examination. The term historiography also refers to the theory and history of historical writing.

-- Historiography, by Britannica

The compilation may have been prompted by concern over deteriorating national spirit. There were disastrous global climate changes of 535-536 and the Plague of Justinian to contend with and the Iranians would have found much-needed solace in the collected legends of their past.

Islamic legend

Following the collapse of the Sassanid Empire [224 to 651] and the subsequent rise of Islam in the region, the Kayanian legends fell out of favour until the first revival of Iranian culture under the Samanids. Together with the folklore preserved in the Avesta, the Khwaday-Namag served as the foundation of other epic collections in prose, such as those commissioned by Abu Mansur Abd al-Razzaq, the texts of which have since been lost. The Samanid-sponsored revival also led to the resurgence of Zoroastrian literature, such as the Denkard, book 7.1 of which is also a historiography of Kayanians. The best known work of the genre is however Firdowsi's Shahnameh "Book of Kings", which, though drawing on earlier works, is entirely in verse.

-- Kayanian dynasty, by Wikipedia