by Ben Westhoff

CityPages

Wednesday, May 10, 2017

Getty images

Shortly after the birth of my mother in Minneapolis in 1948, a man from Sacramento named Charles M. Goethe began sending my grandfather checks to put toward her college education. They were for small amounts — $36 here, $5 there — but they added up.

My mom, Catherine Reed, never met Goethe, and my grandparents didn’t know him in those days either. He was a rich, mysterious stranger who’d suddenly come into their lives.

A banker and real estate developer who promoted environmental causes, Goethe had a junior high school, a park, and an arboretum at Sacramento State named for him. The school’s president proclaimed him “Sacramento’s most remarkable citizen.”

For my grandparents — who were young scientists struggling to make ends meet — Goethe’s largesse was a gift from the gods.

He floated into their orbit after my grandfather became a professor at the University of Minnesota’s genetics institute. Goethe was passionate about the eugenics movement, a then-popular effort to improve America by regulating who could and couldn’t have babies. Ultimately, more than 60,000 American women and men with “undesirable” genes would be sterilized without their consent.

Eugenicists believed traits like criminality and “feeblemindedness” were genetic and could be eliminated from the population by sterilizing those who exhibited them. Thirty-three states permitted eugenic sterilization of those believed to be mentally unfit, promiscuous, criminal, epileptic, or in possession of other objectionable qualities.

Charles M. Goethe was a Hitler apologist who paid for my mom’s college.courtesy of Catherine Reed

Eugenicists also encouraged those of “sound genetic stock” to have more kids. That’s why Goethe was interested in my grandparents, who were both of Northern European ancestry and possessed Ph.Ds. He wanted them to have plenty of successful offspring. My mom graduated from Cornell University in 1969, debt free.

Back then eugenics was not yet a dirty word. For much of the 20th century it was considered a progressive cause with a devoted intellectual following — including doctors, lawyers, and, particularly, academics.

But Goethe took it further than most. He fought immigration, believed in white superiority, and defended Hitler in 1936. Among the Nazis’ many atrocities was the forced sterilization of hundreds of thousands of people under a plan that borrowed heavily from the American blueprint.

Upon Goethe’s 90th birthday in 1965, liberal titans including Lyndon Johnson and Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren paid tribute. He would die a year later. In the decades to follow, public opinion turned sharply.

His name became tainted, unceremoniously stripped from the Sacramento facilities that bore it.

Back in the Twin Cities, my grandfather faced a reckoning. He’d arrived from Harvard to lead the Dight Institute, a new genetics program at the University of Minnesota. In the ’50s and ’60s, he fostered an important new scientific discipline called genetic counseling — advising parents on the likelihood their kids would have hereditary diseases — and was featured in hundreds of magazine and newspaper articles, traveling the world and receiving praise from admirers that included the Pope.

But the source of his University of Minnesota funding, as well as his children’s college, would become increasingly problematic.

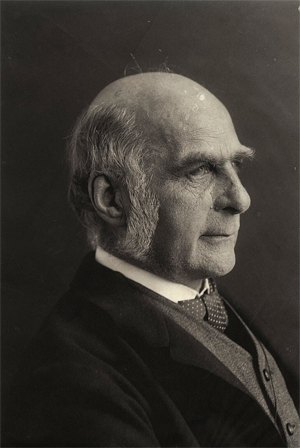

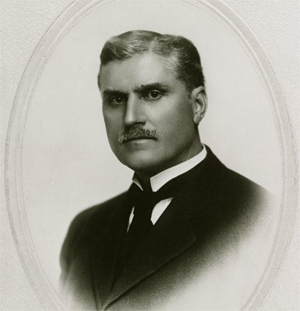

The story begins with the man for whom the institute was named, Charles Dight.

Dight was eccentric, to say the least. He resided in a treehouse. Seriously. It was next to Minnehaha Creek and built on stilts.

He wanted a good view of the creek, he explained, and was worried that if his home sat on the ground, leaves would bunch up against it and create a fire hazard.

It was cozy but not cramped, featuring multiple floors accessed by a spiral iron staircase, a small kitchenette in the cupola, a coal stove, and a pair of porches. Above the front door it read, “Truth Shall Triumph, Justice Shall be Law,” a quote from an anti-slavery sermon. Impressively, he designed the treehouse himself, although it had no sewage connection — which apparently caused someone to report him to the city health department.

He could also be annoying. Dight advocated for countless causes, from pasteurized milk to public hygiene, and always had a leaflet tucked in his pants, ready to talk your ear off. People were known to leave the room when they heard him coming.

Born in Pennsylvania in 1856, Dight trained as a doctor and settled in Minnesota around the turn of the century, a member of Hamline University’s medical college before it was absorbed into the U. The pay was bad, and he supplemented it by working for an insurance company.

In 1914 he was elected to the Minneapolis City Council as a socialist, and led the push for milk pasteurization laws. For his troubles he had a street named after him — Dight Avenue, which runs parallel to Hiawatha Avenue in Longfellow, next to a bunch of grain silos.

The reforms he favored weren’t always what we think of as left-wing causes today. Sure, he was against war, and believed in the “back to the land” movement. But he also crusaded for temperance and strongly believed pigs should be fed the city’s garbage. (The logic? That pigs would get rid of the waste for free and the city could subsequently make money selling the swine.)

Charles Dight, a socialist city councilman who lived in a treehouse, lobbied to sterilize away genetic defects. Courtesy of the University of Minnesota Archives.

Divorced with no kids, he built a huge nest egg by scrimping, saving, and, well, living in a treehouse. Toward the end of his life he finally decided how he’d like to spend his money: on the eugenics movement.

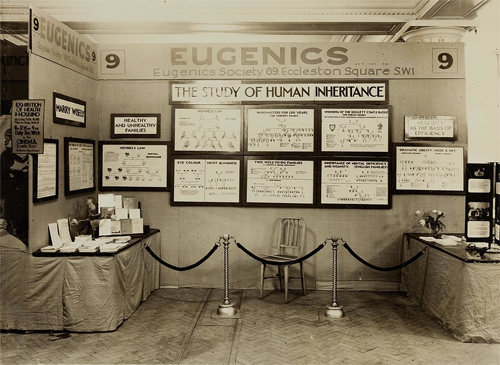

Eugenics initially piggybacked on the findings of Austro-Hungarian scientist (and monk) Gregor Mendel, who, through experiments breeding pea plants, discovered many important laws of heredity.

The eugenicists applied his principles to humans, speculating (without scientific basis) that negative human traits could be stamped from the species through sterilization. Eugenics soon took hold in academia and even received glowing endorsements in mainstream magazines like the Saturday Evening Post and Cosmopolitan.

Intelligence tests became widely administered (with often-flawed or racist methodologies), resulting in scientific classifications like “idiot,” “imbecile,” and “moron,” helping to determine who was eligible for sterilization.

In Minnesota more than 2,300 people were sterilized, mostly between 1928 and 1960. Many were institutionalized at Faribault’s School for the Feebleminded, which housed generations of the “mentally deficient,” “mentally ill,” epileptics, and others beginning in the late 19th century until finally closing in 1998.

Though Dight was a newcomer to the cause, he embraced it full bore. He started the Minnesota Eugenics Society, unsuccessfully lobbied for a eugenics tournament called the “Fitter Family Competition” at the Minnesota State Fair (these contests, popular around the country, awarded medallions to families who scored high on IQ tests and urine and blood samples), and authored a pamphlet called “Human Thoroughbreds, Why Not?”

Breeding quality people should be as much of a priority as breeding horses, he wrote, defining a thoroughbred as a person free of “inheritable defects.”

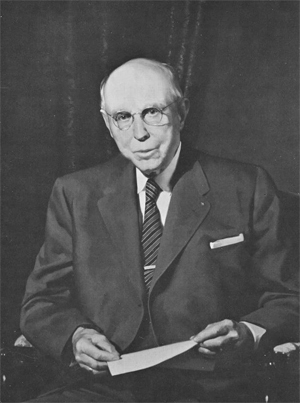

Sheldon Reed at the 1965 World Health Organization conference in Geneva. Courtesy of the University of Minnesota Archives.

The perfect human, in the eyes of most eugenicists, tended to be a white Northern European. Madison Grant’s influential 1916 tome The Passing of the Great Race classified “Nordic” Europeans as the superior race, and helped lay a foundation for Nazism in the process.

Dight took heart when Minnesota passed a sterilization law in 1925, which allowed the “feeble-minded and insane” to be “tubectomized or vasectomized” by order of doctors or psychologists. Dight didn’t feel the law went far enough, however, since it only applied to the institutionalized.

He preferred a law closer to that of Chancellor Adolf Hitler’s Germany, which in 1933 enacted the Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring, permitting the sterilization of anyone possessing a supposed genetic problem ranging from unintelligence to alcoholism to blindness. On August 1 of that year, Dight sent Hitler a note wishing him well on his “plan to stamp out mental inferiority among the German people.”

“I trust you will accept my sincere wish that your effort along that line will be a great success,” he concluded. He received a thank you card with Hitler’s signature.

Dight never learned the full details of the Nazis’ great “success.” He died in 1938 from heart disease. In his will, he left around $100,000 to the University of Minnesota “to promote biological race betterment, better human brain structure and mental endowment by spreading abroad the knowledge of the laws of heredity and the principles of eugenics.”

The U was thrilled, and the Dight Institute was founded in 1941. Six years later they hired my grandfather, Sheldon Reed, to lead it.

There was only one problem. My grandfather wasn’t a eugenicist. He was a human geneticist, focused on how and why maladies were passed from one generation to the next. But human genetics was a nascent field. The eugenicists held many of the purse strings.

Elizabeth Reed, a Ph.D., saw her own career derailed due to the sexist practices of the time. Courtesy of Catherine Reed.

My name is Benjamin Reed Westhoff. I attended elementary school in Mankato, and our family moved to St. Paul before I started seventh grade. We lived a few blocks away from my grandparents’ house in Falcon Heights, where we visited regularly and ate my grandmother’s meatloaf. They spoiled my brother, sister, and me, overpaying for menial chores and offering sugary cereals like Cocoa Pebbles and Lucky Charms for breakfast. At home, all we got was Cheerios.

Grandpa Shelly, as we called him, was bald and short. He wasn’t a big conversationalist, but had a diverse range of interests, from ballroom dancing to nurturing African violets to learning Hmong. One of the few white people who could write the language, he taught illiterate immigrants how to read and write it, and he and my grandmother hosted newly arrived Hmong families at their house until they could get on their feet.

Back in 1947, he was new to Minnesota and barely getting by on a modest academic salary. He had just married my grandmother, Elizabeth Reed, a scientific powerhouse herself who was raised poor on an Ohio farm, washed laboratory glassware to pay her way through Ohio State, and earned a Ph.D. in biology when it was uncommon for women.

Elizabeth’s first husband was killed in World War II, and she had a young son, whom Shelly helped raise.

As was customary at colleges at the time, nepotism rules precluded the spouses of U professors from becoming professors themselves, a practice that continued until about 1970. Though she taught biology and genetics at the U’s College of Continuing Education and at Macalester and Hamline, and co-authored important studies on psychoses and mental disabilities with my grandfather, her career was largely derailed owing to the sexist norms of the time.

The Dight Institute, housed in the zoology building, had a skeleton staff at first. Part of Shelly’s job was raising money. As anyone who’s ever fundraised can tell you, this is often a huge pain. But shortly after starting he began a promising correspondence with the wealthy Charles Goethe.

“I am intensely interested in your appointment to be Director of the Dight Institute,” Goethe wrote in 1947. “We were in touch with Dr. Dight over a long period of years.”

Ben Westhoff: His mom had no idea her benefactor defended Hitler. Photo by Jay Senter.

It was a short letter and bore the Eugenics Society of Northern California’s logo. In February, 1948 Goethe asked if Shelly would be interested in “occasional small checks” for his department “toward getting you really at work on some Eugenics research.”

Shelly gladly accepted the checks, but from the start it was pretty clear he wasn’t doing eugenics. His big thing was genetic counseling, a term he coined. It examined a subject’s hereditary history to determine the odds that his or her offspring would have health problems.

This much was appealing to the eugenicists. But whereas they might have used the information to sterilize those with “defective” genes, Shelly instead helped people understand their situations so they could decide whether or not to have kids.

Dight staffers counseled thousands of people. DNA testing hadn’t yet been invented — it wasn’t even discovered until 1953 — and many nervous parents were grateful for his services.

Human genetics was becoming mainstream, and Shelly was regularly featured in newspapers. He was asked to weigh in on the controversial paternity case levied by actress Joan Barry against Charlie Chaplin. (Chaplin couldn’t have been the father, my grandfather insisted, after comparing the results of the parties’ blood tests — which the court, who ruled Chaplin the father, for some reason ignored.)

“Got Genes? Then You Must Read This Book,” read a Minneapolis Sunday Tribune headline in 1955, giving serious column inches to Shelly’s first book, Counseling in Medical Genetics. The tome was a hit, selling briskly around the world. It was translated into Italian by the Vatican Press, and Pope Pius XII himself praised it at a 1958 conference on blood transfusion in Rome.

“The effect of genetic consultation,” he said, “is to encourage parents to have more children than they would have had without it because the possibilities of having an unhappy case are less than they think.”

Though Shelly and Elizabeth lived modestly, his work was often glamorous. He hobnobbed and raised money alongside wealthy Minneapolis elites like the Cowles family, who owned the Minneapolis Star and the Tribune. Shelly sailed on luxury liners to conferences and visited genetics institutes in New Delhi, Tokyo, and Stockholm. The World Health Organization made him an adviser, and he spoke in Geneva.

There appears to have been occasional tension with Goethe. After all, Shelly spent his time on genetic counseling, not eugenics. In one letter Goethe emphasized that his money should be used for EUGENICS, in all caps. But for the most part he liked Shelly’s work, and their relationship grew personal in 1948.

“Last but not least in my personal opinion,” Shelly ended his March 9 correspondence that year, “is the fact that my wife and I became the parents of a daughter this last week end.”

“I am thrilled to hear of the arrival of the young lady,” Goethe wrote back immediately. “Will you permit me to send you the enclosed modest check to start the bank account for her college education?”

The amount is unknown, but this was the first of many he sent on her behalf, and for my uncle, born three years later. Though Goethe and my mother never met, he became increasingly enamored of her. “I often look at her sweet smile from the picture I have at my desk at the ranch’s office,” he wrote in 1953 as she turned five. “She is all you say.”

Was Goethe a bad dude? In some ways, yes. Definitely yes. He supported Hitler’s early eugenics efforts, and in 1936 even defended the “honest yearnings for a better population” at a time when Hitler’s persecution of Jews was well known.

He argued for limiting immigration, as did many eugenicists, whose lobbying efforts helped convince Congress to pass the Emergency Immigration Restriction Act of 1921, which dramatically curtailed the number of new arrivals from Southern and Eastern Europe.

This meant hundreds of thousands of Jews were denied entry to the U.S. in the run-up to World War II. My dad’s mother’s family, Orthodox Jews from Romania, made it in just under the wire. In 1941, Anne Frank’s father petitioned a U.S. official, in vain, to allow his family in.

On the other hand, Goethe’s efforts inarguably made life better for many in Sacramento and beyond. As a teen he began working for his father, a banker, and they developed much of the residential property in East Sacramento.

When he was a young man and his future wife denied his initial marriage proposal — “I don’t propose to marry a money-making machine” — he vowed to invest the bulk of their money in “human betterment.” Before long he quit the bank and they established Sacramento’s first playground and founded an orphanage.

He fought to save redwoods, contributed huge sums to Sacramento State, and helped launch the “interpretive parks” movement, which brought educational programs to the national park system.

As for my grandfather, I’m not the best person to conduct a moral evaluation. I will admit that it looks bad how willing he was to work with the eugenicists and accept their money, though he later said he didn’t know Dight supported Hitler.

Also interesting was his 1983 interview with City Pages, after his retirement, for a piece exposing the Dight Institute’s eugenics ties. He told writer Patricia Ohmans that he, like other geneticists, didn’t have a problem with the basic goal of improving society through better breeding, “but we still don’t know how to eliminate genes in any sensible fashion.”

Was Shelly a eugenicist in a geneticist’s lab coat? It doesn’t appear so. After spending days digging through the Dight Institute archives at the University of Minnesota, I’ve found no evidence he ever supported forced sterilizations or espoused racist, anti-immigrant viewpoints. He never argued for genetic superiority. And he and the Dight Institute ultimately failed to spread the principles of eugenics, as Dight had stipulated in his will.

In fact, it’s fair to say Shelly’s views on race were ahead of their time. In the archives was a draft of an address he delivered in 1951 at St. Mark’s Cathedral entitled “All Men Are Brothers Under the Skin.”

Families that couldn’t have kids would ask what type of babies they should adopt. In his book Counseling in Medical Genetics, published in 1955, he suggested that children of “mixed race ancestry” would make an excellent choice. At a time when interracial marriages were illegal in many states, these children were only “illegitimate because of social prejudice and pressure against a marriage that would have provided legitimacy.”

In one undated paper called Color of the U.S.A. — 3000 A.D., he addressed a question that white civil rights advocates sometimes heard: “Would you want your daughter to marry a Negro?”

“My answer is that is I want my daughter to marry whom she chooses,” he answered. “If her choice be a Negro, he has my approval in advance, as I trust her judgment completely.”

Growing up, I was proud of my family’s liberalism. My mother and grandmother were crusading feminists and abortion rights activists. Shelly was on Minnesota Planned Parenthood’s board of directors for many years. I volunteered for Sandy Pappas’ losing St. Paul mayoral campaign against Norm Coleman in 1997. Though I no longer live here, I still cheerlead for Minnesota’s enlightened Scandinavian liberalism, and am proud the state gave its electoral votes to Hillary Clinton.

But let’s be honest: Minnesota has a messed-up racial history.

It’s overwhelmingly white — 85 percent at the last census — and dominated by Northern European ancestry. These demographics are at least partly owing to the racist immigration laws enacted 100 years ago.

In recent decades the Twin Cities has welcomed large populations of Hmong and Somali immigrants, but racial earning disparities here are some of the worst in the nation. (To be fair, these populations haven’t had many generations to assimilate.)

That doesn’t mean things were handed to my grandparents on a platter. It’s true that Goethe saw my grandmother as sound genetic stock. Her family was Scotch-Irish and German, and she was intelligent.

But while he and other eugenicists believed that one’s genes largely determined one’s fate — that nature was far more important than nurture — this was not the case with Elizabeth, who died in 1996. Held back by gender discrimination, her environment affected her career more than her DNA.

“Elizabeth was pretty angry and bitter about this most of her life, because she was smarter and more hard-working than most men who got positions above her,” my mother told me.

My mom faced discriminatory advising herself at Cornell in the late ’60s, when she was exploring post-college options. “One of my advisers said women should not go to graduate school,” she says.

Eventually, she received a Doctor of Arts degree from the University of Northern Colorado and became an entomologist researcher for the U in the late ’80s. Like her mother, she never landed a tenure-track position, and in 2004 became an artist.

She doesn’t regret taking Goethe’s money. “It started when I was a baby, and I don’t think it’s anything I should be ashamed of,” she says. She had no idea he’d defended Hitler. Even so, that knowledge wouldn’t have changed her actions. “I would be totally opposed to his values, but I believe in the idea that you can take the devil’s money and do God’s work with it.”

Considering he died while she was in college, and she went into a different field, it wasn’t hard for her to avoid being tainted by Goethe’s money. It would have been much more difficult for my grandfather, but he seems to have avoided the trap too.

In fact, as I began to dig deeper into his academic archive, something particularly interesting emerged: It turns out that a study he published with my grandmother truly frustrated the eugenicists’ scientific case.

Back in the 1920s, many worried that dumb, loose women were running around having sex and birthing hordes of mentally deficient babies. No joke.

Eugenicists believed in a theory called “differential fecundity,” which held that low-intelligence women had stronger sex drives, and thus birthed more children. Since the smart women were only reproducing in modest numbers, society was therefore slowly dumbing itself into oblivion. (You may recall this as the plot of Idiocracy.) Thus the urgent necessity to sterilize these horny, rampaging women.

The only problem is the theory was baloney. My grandparents dispelled it in their 1965 book Mental Retardation: A Family Study. (You’ll have to excuse the title. “Mental retardation” was considered an acceptable scientific term at the time, applied to anyone with an IQ under 70.)

By that point eugenics fervor had slowed and the second wave of feminism was taking hold, but the basic principle of differential fecundity was still believed by many. Elizabeth was the lead author of the study, which surveyed over 80,000 people. It was the largest ever of its kind, an attempt to understand how mental deficiency was passed from generation to generation, and how society was impacted.

Turns out we weren’t turning into a nation of idiots. “Our work shows that the intelligence of the population is not dropping rapidly and that it might be increasing slowly,” it concludes, noting that “while a few of the retarded produce exuberantly large families of children with low average intelligence, most of the retarded produce only one child or no children at all.”

The book tackled difficult questions, like what to do about would-be parents who didn’t have the mental capacity to care for offspring. My grandparents recommended voluntary sterilization, so long as the subjects’ own parents or guardians gave consent. (The sterilization of the “intellectually disabled,” as it’s now known, remains a controversial issue to this day.)

Mental Retardation: A Family Study was reviewed as “monumental” and a “landmark.” At the time of its release, the eugenics movement was on its way out, and my grandparents’ findings only accelerated its demise.

The Dight Institute wasn’t long for this world either. Shelly retired in 1978, and without a strong successor, chaos ensued. In the coming decade it was renamed the Institute of Human Genetics and folded into the medical school. This was done not so much because of controversy over Dight or eugenics itself, but because the institute’s methods were growing obsolete. Human genetics had become medicalized, and genes were increasingly being studied at the molecular level, rather than through surveys and probability charts.

“At the Dight Institute, they were old-fashioned geneticists,” notes Neal Ross Holtan, medical director of St. Paul-Ramsey County Public Health, who authored his Ph.D. dissertation on Shelly, the Dight Institute, and eugenics.

Genetic counseling, however, is still practiced to this day.

Sane people now agree that attempting to improve society by stripping away individuals’ reproductive sovereignty is a bad idea. But it’s trickier to pass judgment on people from another time. Was Dight an inspired activist or an overzealous, naive kook? Was Goethe a humanitarian or a monster? What about my grandfather?

Ultimately, these questions are probably moot. Dight’s name is gone from the genetics institute, Goethe’s name has been removed from Sacramento institutions he helped foster, and my grandfather, who passed in 2003, doesn’t even have a Wikipedia page. They’re now officially obscure. Time will only make them more so.

Except, of course, to people like me. The people who knew and loved them.

To me, Shelly will always be the guy who let me dig my grubby little paws into a full box of Froot Loops to retrieve a plastic toy. He’ll always be the guy who gave me a special little present on each of my siblings’ birthdays, so I wouldn’t feel too left out. He’ll always be my grandpa. And that means more to me than any paper he wrote.