by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/6/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

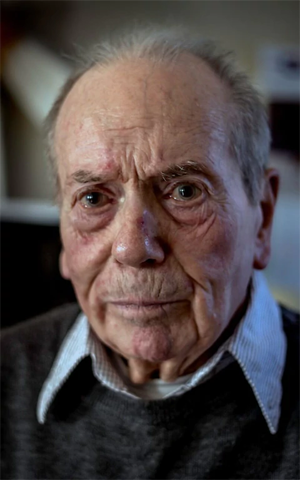

Rolf Alfred Stein (13 June 1911 – 9 October 1999) was a German-born French Sinologist and Tibetologist. He contributed in particular to the study of the Epic of King Gesar, on which he wrote two books, and the use of Chinese sources in Tibetan history. He was the first scholar to correctly identify the Minyag of Tibetan sources with the Xixia of Chinese sources.

Stein was born in Schwetz (now Świecie, Poland) to a family of Jewish origin in 1911. As a young man, Stein became interested in the occult, and it was from there that his interest in Tibet began.

He received his first degree in Chinese from the Seminar für Orientalische Sprachen at the University of Berlin in 1933. He fled to France the same year. He obtained degrees from l'École nationale des langues orientales vivantes in Chinese (1934) and Japanese (1936). In Paris he studied Tibetan with Jacques Bacot and Marcelle Lalou. He became a French citizen on 30 August 1939. Stein spent the Second World War in French Indo-China, working as a translator and where he was taken prisoner by the Japanese. He completed his doctorat d'État in 1960 on the Gesar epic.

Stein was a professor at the École pratique des hautes études, Ve section (Religions de la Chine et de la Haute Asie) from 1951 until 1975. He was a professor at the prestigious Collège de France from 1966 until 1982. He died in 1999. He was married to a Vietnamese lady from the highlands and adopted a daughter of Vietnamese-French descent.

Among Stein's most notable students were Anne-Marie Blondeau, Ariane Macdonald-Spanien, Samten Karmay, Yamaguchi Zuiho, and Yoshiro Imaeda.

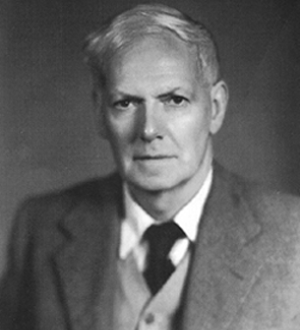

Samten Gyeltsen was born in 1936 in Sharkhog, eastern Tibet. He received religious training in Dzogchen meditation from his uncle. He completed his studies in the Bon monastery in 1955, obtaining the degree of geshe, and left with a group of friends to Drepung Monastery, a Gelug gompa near Lhasa. The monastery was known for its high philosophical training.

After leaving Drepung due to the difficult political situation, Samten moved to Nepal and later to India. After working for some time in Delhi, he was invited to England by David Snellgrove under a Rockefeller fellowship. Upon moving to Europe, he assumed the surname Karmay. He studied under two mentors, Snellgrove and Rolf Stein, who both recognized Samten's knowledge of Tibetan texts. He earned an M. Phil degree at the SOAS, University of London.

In 1980 he moved to France, where he entered the Centre national de la recherche scientifique (National Centre for Scientific Research). During his time there, he was awarded with the CNRS Silver Medal for his contribution to Human Sciences. A number of Revue d'Etudes Tibétaines was dedicated to him in November 2008. He also held the post of the President of the International Association of Tibetan Studies between 1995 and 2000, being the first Tibetan to be elected to the post. In 2005 he was a visiting professor at the International Institute for Asian Studies, under the sponsorship of Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai (""Society for the Promotion of Buddhism"").

-- Samten Karmay, by Wikipedia

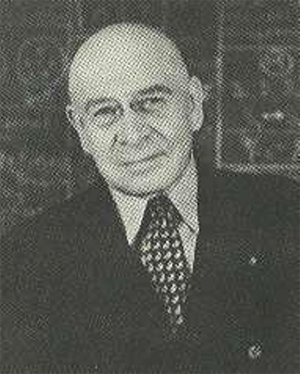

Yoshiro Imaeda (Japanese: 今枝 由郎 Hepburn: Imaeda Yoshirō, born 1947) is a Japanese-born Tibetologist who has spent his career in France. He is director of research emeritus at the National Center for Scientific Research in France.[1]

Born in Aichi Prefecture, Imaeda graduated from the Otani University Faculty of Letters, where he studied with Shoju Inaba, under whose advice he pursued graduate studies in France, where he earned his Ph.D. at Paris VII. He began work at the CNRS in 1974. Between 1981 and 1990, he worked as an adviser to the National Library of Bhutan Bhutan. In 1995, he was a visiting professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and has also held a visiting appointment at Columbia University.

His research has focused on Dunhuang Tibetan documents, but he has also translated the poems of the VI Dalai lama, and produced a catalog of Kanjur texts.

-- Yoshiro Imaeda, by Wikipedia

Works of Rolf Stein

• 1939 "Leao-tsche", T'oung Pao, XXXV: 1-154

• 1939 "Trente-fois fiches de divination tibétaines", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, IV : 297-372

• 1941: “Notes d'étymologie tibétaine.” Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient, XLI: 203–231

• 1942 "Jardins en miniature d'Extrême-Orient, le Monde en petit", Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient (Hanoi, Paris), XLII: 1-104 [publ. 1943]

• 1942 "A propos des sculptures de bœufs en métal", Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient (Hanoi, Paris), XLII: 135-138 [publ. 1943]

• 1947 "Le Lin-yi, sa localisation, sa contribution à la formation du Champa et ses liens avec la Chine", Han-hiue, Bulletin de Centre d’études sinologiques de Pekin, II : 1 -335

• 1951 "Mi-nag et Si-hia, géographie historique et légendes ancestrales", Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient (Hanoi, Paris), XLIV (1947–1950), Fasc. 1, Mélanges publiés en l'honneur du Cinquantenaire de l'École Française d'Extrême Orient

223-259

• 1952 "Chronique bibliographique: récentes études tibétaines", Journal Asiatique, CCXL : 79-106

• 1952 "Présentation de l'œuvre posthume de Marcel Granet: 'Le Roi boit,'" Année Sociologique, 3e série : 9-105 [publ. 1955]

• 1953 "Chine", Symbolisme cosmique et monuments religieux, Musée Guimet, Catalogue de l'exposition, Paris : 31-40

• 1956 L'épopée tibétaine de Gesar dans sa version lamaïque de Ling, Paris, Annales du musée Guimet, Bibliothèque d'études, LXI

• 1957 "L'habitat, le monde et le corps humain", Journal Asiatique, CCXLV : 37-74

• 1957 "Architecture et pensée religieuse en Extrême-Orient." Arts asiatiques IV : 163-186

• 1957 "Les religions de la Chine", Encyclopédie française. Paris, tome 19 : 54.3-54.10

• 1957 "Le linga des danses masquées lamaïques et la théorie des âmes", Lieberthal Festschrift, Sino-Indian Studies V, 3-4, ed. Kshitis Roy. Santiniketan : 200-234

• 1958 "Les K'iang des marches sino-tibétaines, exemple de continuité de la tradition", Annuaire de l'École pratique des Hautes Études, Ve section, Paris, 1957-58 : 3-15

• 1958 "Peintures tibétaines de la vie de Gesar", Ars Asiatique, V, 4 : 243-271

• 1959 Recherches sur l'épopée et le barde au Tibet. Paris: Bibliothèque de l'Institut des Hautes Études chinoises, XIII.

• 1959 "Lamaïsme", Le Masque, Catalogue de l'exposition, décembre 1959-septembre 1960, Musée Guimet. Paris: Éditions des Musées nationaux: 42-45.

• 1961 Les tribus anciennes des marches sino-tibétaines. Paris: Bibliothèque de l'Institut des Hautes Études chinoises, vol. XV.

• 1961 Une chronique ancienne de bSam-yas : sBa-bzed, édition du texte tibétain et résumé français. Paris: Bibliothèque de l’Institut des Hautes Études chinoises, Textes et Documents.

• 1961 "Le théâtre au Tibet." Les théâtre d'Asie. Paris: CNRS : 245-254

• 1962 Civilization Tibetain

• 1962 "Une source ancienne pour l'histoire de l’épopée tibétaine, le Rlans Po-ti bse-ru" Journal Asiatique 250: 77-106.

• 1963 "Remarques sur les mouvements du taoïsme politico-religieux au 1 Ie siècle après Jésus-Christ." T'oung Pao 50.1-3: 1-78.

• 1963 "Deux notules d'histoire ancienne du Tibet." Journal Asiatique 251: 327-333

• 1964 "Une saint poète tibétain." Mercure de France, juillet-aout 1964 : 485-501

• 1966 "Nouveaux documents tibétains sur les Mi-nag / Si-hia", Mélanges de sinologie offerts à Monsieur Paul Demieville. Paris: Bibliothèque de l’Institut des Hautes Études chinoises, XX, vol. 1: 281-289

• 1966 Leçon inaugurale, Collège de France, Chaire d’étude du monde chinois: Institutions et concepts. Paris: Collège de France.

• 1968 "Religions comparées de L'Extrême-Orient et de la Haute-Asie", Problèmes et méthodes d'histoire des religions. École pratique des Hautes Études, Ve section — Sciences Religieuses. Paris: Presses universitaires de France: 47-51

• 1969 "Un exemple de relations entre taoïsme et religion populaire." Fukui hakase shôju kinen Tôyô bunka ronshû. Tôkyô : 79-90

• 1969 "Les conteurs au Tibet." France-Asie 197: 135-146.

• 1970 "Un document ancien relatif aux rites funéraires des Bon-po tibétains." Journal Asiatique CCLVIII: 155-185

• 1970 "La légende du foyer dans le monde chinois." Échanges et communications: Mélanges offerts à Claude Lévi-Strauss, reunis par Jean PouUon et Pierre Miranda. The Hague: Mouton. 1280-1305

• 1971 "Illumination subite ou saisie simultanée, note sur la terminologie chinoise et tibétaine." Revue de l'histoire des religions CLXXIX: 3-30.

• 1971 "La langue zan-zun du Bon organisé", Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient LVIII: 231-254

• 1971 "Du récit au rituel clans les manuscrits tibétains de Touen-houang." Études tibétaines dédiées à la mémoire de M. Lalou. éd. Ariane Macdonald, Paris, A. Maisoneuve : 479-547

• 1972 Vie et chants de 'Brug-pa Kun-legs, le yogin, traduit du tibetain et annoté. (Collection UNESCO d’œuvres représentatives). Paris: G.-P. Maisoneuve et Larose

• 1973 "Le texte tibétain de "Brug-pa Kun-legs", Zentralasiatische Studien 7:9-219

• 1973 "Un ensemble sémantique tibétain: créer et procréer, être et devenir, vivre, nourrir et guérir", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies XXXVI : 412-423

• 1974 "Vocabulaire tibétain de la biographie de 'Brug-pa Kun-legs", Zentralasiatische Studien 8 : 129-178

• 1976 "Préface." Choix de documents tibétains conservés à la Bibliothèque nationale complété par quelques manuscrits de l'India Office et du British Museum. Ariane Macdonald et Yoshiro Imaeda. Paris: Bibliothèque nationale, tome 1: 5-8

• 1977 "La gueule du makara: un trait inexpliqué de certains objets rituels." Essais sur l'art du Tibet. éd. par Ariane Macdonald et Yoshirô Imaeda. Paris: A. Maisonneuve: 53-62

• 1978 "À propos des documents anciens relatifs au phur-bu (kïla)." Proceedings of the Csoma de Kôrôs Memorial Symposium. éd. L. Ligeti. Budapest: 427-444

• 1979 "Religious Taoism and Popular Religion from the Second to Seventh Centuries", Facets of Taoism: Essays in Chinese Religions. ed. H. Welch and A. Seidel, Yale University Press: 53-81

• 1979 "Introduction to the Gesar Epic", The Epic of Gesar. 25 vol., Thimpu: Bhutan, vol.1: 1-20.

• 1980 "Une mention du manichéisme dans le choix du bouddhisme comme religion d'Etat par le roi Khri-sron lde-bstan", Indianisme et Bouddhisme, Mélanges offerts à Mgr Etienne Lamotte. Louvain-La-Neuve: Publications de l’Institut Orientaliste de Louvain, 23: 329-338

• 1981 "Bouddhisme et mythologie. Le problème", Dictionnaire des mythologies et des religions des sociétés traditionnelles et du monde antique (sous la direction de Yves Bonnefoy), Paris, Flammarion, vol. 1 : 127-129

• 1981 "Porte (gardien de la) : un exemple de mythologie bouddhiste, de l'Inde au Japon", Dictionnaire des mythologies et des religions des sociétés traditionnelles et du monde antique. (sous la direction de Yves Bonnefoy), Paris, Flammarion, vol. 2 : 280-294.

• 1981 "Saint et Divin, un titre tibétain et chinois des rois tibétains." Numéro spécial — Actes du Colloque international (Paris, 2-4 octobre 1979) : Manuscrits et inscriptions de Haute-Asie du Ve au Xe siècle. Journal Asiatique, CCLIX, 1 et 2 : 231-275.

• 1983 "Tibetica Antiqua I: Les deux vocabulaires des traductions indo-tibétaines et sino-tibétaines dans les manuscrits Touen-Houang", Bulletin de l'École Française d'Extrême Orient LXXII: 149-236.

• 1983 "Notes sur l’esthétique d'un lettre chinois pauvre du XVIIe siècle", Revue d’esthétique, nouvelle série n° 5, Autour de le Chine: 35-43.

• 1984: "Allocution", Les peintures murales et les manuscrits de Dunhuang (Colloque franco-chinois organisé à la Fondation Singer-Polignac à Paris, les 21, 22 et 23 février 1983) ed. M. Soymie, Paris, Éditions de la Fondation Singer-Polignac : 17-20.

• 1984 "Quelques découvertes récentes dans les manuscrits tibétains." Les peintures murales et les manuscrits de Dunhuang, Paris, Éditions de la Fondation Singer-Polignac : 21-24.

• 1984 "Tibetica Antiqua II: L'usage de métaphores pour des distinctions honorifiques à l’époque des rois tibétains", Bulletin de l'École Française d'Extrême Orient LXXIII: 257-272.

• 1985 "Tibetica Antiqua III : À propos du mot gcug-lag et de la religion indigène." Bulletin de l'École Française d'Extrême Orient LXXIV: 83-133

• 1985 "Souvenir de Granet", Etudes chinoises IV. 2 : 29-40

• 1986 "Tibetica Antiqua IV : La tradition relative au début du bouddhisme au Tibet." Bulletin de l'École Française d'Extrême Orient LXXV: 169-196.

• 1986 "Avalokitesvara / Kouan-yin, un exemple de transformation d'un dieu en déesse." Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie II: 17-80.

• 1987 Le monde en petite : jardins en miniature et habitations clans la pensée religieuse d'Extrême-Orient. Paris, Flammarion.

• 1987 "Un genre particulier d'exposés du tantrisme ancien tibétain et khotanais." Journal Asiatique CCLXXV. 3-4 : 265-282.

• 1988: "Tibetica Antiqua V : La religion ingene et les bon-po dans le manuscrits de Touen-houang", Bulletin de l'École Française d'Extrême Orient LXXVII: 27-56

• 1988 "La mythologie hindouiste au Tibet", Orientalia Iosephi Tucci memoriae dicata. Rome: Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente : 1407-1426

• 1988 "Grottes-matrices et lieux saints de la déesse en Asie Orientale", Paris Bulletin de l'École Française d'Extrême Orient CLI, 106 p

• 1988 "Les serments des traités sino-tibétains (8e-9e siècles), T'oung Pao LXXXIV : 119-138

• 1990. "L’Épopée de Gesar dans sa Version Écrite de l’Amdo" in Skorupski, T. (ed.) 1990. "Indo Tibetan Studies: Papers in Honour and Appreciation of David L. Snellgrove's contribution to Indo-Tibetan Studies" Buddha Britannica, Institute of Buddhist Studies. Series II. Tring. 293-304.

• 1990 The World in Miniature: Container gardens and Dwellings in Far Eastern religious Thought. trans. Phyllis Brooks. Stanford University Press. (translation of Stein 1987)

References

• Obituary at Tibet.ca

• Biography at the École française d'Extrême-Orient. (in French)

• Rolf Alfred Stein official website