Indian Communist Party Strategy Since 1947

by John H. Kautsky

University of Rochester

April, 1955

EVER SINCE its beginning, the Communist Party of India has sought to adhere to international Communist strategy as determined in Moscow, though it has not at all times been equally prompt or successful in making the required changes. It has always attempted to give the same answers as Moscow to the three main questions determining Communist strategy: who was, at any time, the main enemy and consequently what classes and groups were eligible as allies of Communism and what type of alliance was to be formed with them. A study of CPI strategy thus throws light on the development of international Communist strategy in general, particularly in the period since the end of World War II when changes in the CPI line have been much more clearly marked than some of the corresponding shifts in Moscow.1

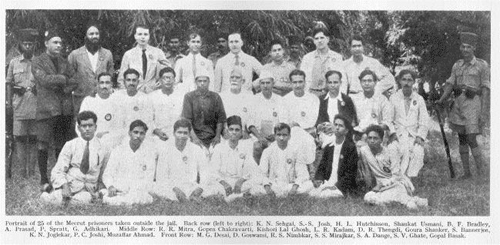

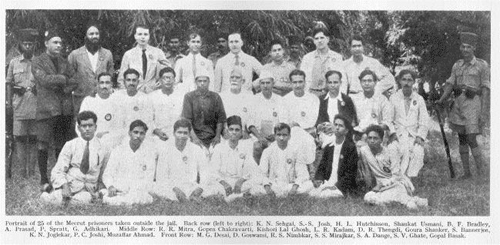

Organized as an all-India party as late as 1933, the Communist Party of India began its career following the "left" strategy of Communism as it had been laid down by the 6th Congress of the Communist International in 1928. This strategy characteristically considered capitalism and the native bourgeoisie as enemies at least as important as feudalism and foreign imperialism and therefore looked forward to an early "socialist" revolution merging with, or even skipping, the "bourgeois-democratic" revolution. It sought a united front "from below" by appealing to workers and also the poor peasantry and petty bourgeoisie as individuals or in local organizations to leave nationalist, labor and bourgeois parties and work with the Communists. Though it thereby isolated itself from the great Indian nationalist movement, the CPI, according to this "left" strategy, denounced the National Congress as "a class organization of the capitalists" and the Congress Socialist Party as "Social Fascists.'"

When Moscow finally recognized the danger posed by German Fascism and changed its foreign policy and, correspondingly, the strategy of international Communism, the CPI, too, after some delays, obediently switched to the "right" strategy as it had been ordered to do at the 7th Comintern Congress of 1935. This strategy regarded imperialism and feudalism (or, in Western countries, Fascism) as the Communists' main enemies and therefore envisaged first a "bourgeois-democratic" and only later a "proletarian-socialist" revolution. It called for an alliance of the Communist Party with anti-imperialist and anti-feudal (or anti-Fascist) parties, both labor and bourgeois, a united front "from above" or popular front. Accordingly, the CPI began to seek unity with the Indian Socialists and the Congress, now referred to as "the principal anti-imperialist people's organization," although, it may be noted, these groups, unlike the Communists' new popular front allies in the West, were much more anti-British than anti-Nazi or anti-Japanese.

Although it was rather unnecessary (because of this last-mentioned peculiar Indian situation), the CPI, like all Communist parties at that time, shifted back from the "right" to the "left" strategy after the conclusion of the Stalin-Hitler Pact of August 1939, once again "unmasking" its erstwhile allies as "reformists" and "agents of imperialism" and denouncing the war against the Axis as "imperialist." While this line proved not unpopular in India, the return to the "right" after the German invasion of Russia in June 1941, which eventually resulted in such growth in Communist strength and prestige in the West and in Southeast Asia, proved disastrous for the CPl's reputation in India, for the Party's new ally was to be Britain, still widely regarded as India 's main enemy. Only under great pressure, especially from the Communist Party of Great Britain, long the CPI's mentor, could the Party be prevailed upon to shift from the line of "imperialist war" to that of "people's war."

In accordance with the continuing wartime alliance of the Great Powers and the participation of Communists in Western coalition governments, Moscow apparently expected the CPI, too, to persist in the postwar period in its adherence to the "right" strategy of cooperation not only with the Congress and Socialists but also the Moslem League, and even to combine this, at least until the end of 1945, with a relatively friendly attitude toward the British. Emerging from the war isolated and demoralized and receiving little or no guidance from Moscow (which was then preoccupied with Europe rather than Asia), the CPI could, in view of these utterly unrealistic expectations, only follow a hesitant, bewildered "right" course,3 for the groups with which it was expected to form a united front were strongly opposed both to the Communists and to each other. For a period in 1946 a faction gained the upper hand in the leadership of the frustrated CPI which, as was especially indicated in the Central Committee resolution "Forward to Final Struggle for Power" (People's Age, Bombay, August 11, 1946), even switched its strategy temporarily back to the "left." This was a fact of some importance because it was during this period that the Communists seized the leadership of a peasant uprising in the backward Telengana district of Hyderabad, which was destined to continue for five years and to play a crucial part in CPI strategy discussions. This "left" anti-Congress line was not, however, acknowledged by Moscow which, though clearly anti-British by now, remained uncertain in its attitude toward the Congress. By the end of 1946, the CPI had returned to the "right" strategy of attempted cooperation with the "progressive" wing of the Congress and also the Moslem League, and when the Mountbatten Plan of 1947 announced the forthcoming division of India as well as during the subsequent communal riots, the CPI repeatedly pledged its support to Nehru and "the popular Governments" of India and Pakistan, notably in its so-called Mountbatten Resolution (People's Age, June 29, 1947).

In the meantime, however, Moscow, along with its policy of more conciliatory relations with the West, was giving up the "right" strategy for international Communism. In June 1947 a session on India of the USSR Academy of Sciences (in Moscow) strongly denounced -- at the very time when the CPI was praising part of it -- the entire Congress, including Nehru, as an ally of imperialism and advocated instead an anti-imperialist movement led by the Communists. While thus agreeing on the abandonment of the "right" strategy of cooperation with the Congress "from above," this session also marked the beginning of a striking disagreement in Moscow (hardly even noticed by outside observers at the time) on the strategy to be substituted for it. V. V. Balabushevich and A.N. Dyakov, the two chief Soviet experts on India, identified the entire bourgeoisie with imperialism and thus, by implication, favored a return from the "right" to the "left" strategy with its proletarian, anti-capitalist approach.5 E. M. Zhukov, the head of the Academy's Pacific Institute, on the other hand, condemned only the "big" bourgeoisie,6 thus leaving the way open to cooperation by the "working class" (i.e., the Communists) not only with peasants and the petty bourgeoisie, as under the "left" strategy, but also with the so-called "medium" or "progressive" capitalists. This was to be accomplished, not as under the "right" strategy through a united front "from above" with the capitalists' parties, but rather through the united front "from below" against these parties, an approach hitherto associated only with the "left" strategy.

Zhukov thus introduced the essential element of a strategy until then unknown to international Communism, but destined to become within only a few years its almost universally applied line. This strategy had first been developed in China by Mao Tse-tung during World War II as the anti-imperialist and anti-feudal strategy of the "bloc of four classes" leading to the "new democracy" rather than immediately to the "socialist" revolution. It implied that the Communist Party itself, not in alliance with the major bourgeois and labor parties, was now considered the true representative of the interests not only of the exploited classes but also of the capitalists. The "left" Dyakov-Balahushevich line and the new Zhukov line existed side by side in Moscow for about two years, strongly suggesting that the differences between them and the general import of the new strategy were not yet appreciated there and perhaps also that Moscow at that time seriously underestimated the Chinese Communists' prospects of victory.

Far from explaining its switch of strategy, Moscow, less interested then in Asian affairs than later, did not even inform the CPI of it, but let it continue its reluctant adherence to the unsuccessful "right strategy." Only through the much more publicized speech by Zhdanov on "The International Situation" (For a Lasting Peace, for a People's Democracy!, November 10, 1947) to the founding meeting of the Cominform in September 1947 did the CPI become aware of the change in the international line. That speech, expounding the thesis of the division of the world into two camps, did not, however, clearly favor either the "left" or the new alternative to the "right" strategy. It was almost exclusively concerned with the situation in Europe and the role of the United States, though its general anti-imperialist (rather than anti-capitalist) tenor could be interpreted as favoring the new strategy, a possibility generally overlooked at the time, when any abandonment of the "right" strategy of international Communism was widely regarded as necessarily tantamount to a return to the "left." At any rate, the Zhdanov thesis was interpreted as calling for a turn to the new strategy in an important article by Zhukov on "The Growing Crisis of the Colonial System" (Bolshevik, December 15, 1947), which, this time, expressly included the "middle bourgeoisie" in the Communist united front "from below." Nevertheless, both Balabuchevich and Dyakov continued to champion the "left" strategy for India; the uncertainty between the two strategies in Moscow had apparently not yet been resolved or perhaps even recognized.

Weakened by lack of guidance from abroad, by factionalism and by internal discontent with the "right" strategy, the CPI leadership eagerly executed what it interpreted to be the change of line desired by Moscow. In December 1947, soon after the full text of Zhdanov's speech had become available to it, the Central Committee of the CPI met and adopted a resolution, "For Full Independence and People's Democracy" (World News and Views, January 17, 1948), signaling the abandonment of the "right" strategy and containing all the essential elements of the "left" strategy. It sharply attacked both the entire Congress (thus turning from the "right" strategy) and the entire bourgeoisie (thus failing to follow the new strategy) as allies of imperialism, favored a united front "from below" against them, looked forward to an early anti-capitalist revolution (another characteristic of the "left" strategy alone) and implied that the use of violent methods was in order, as Zhdanov's speech, too, had done with reference to the colonial areas.

B. T. Ranadive, who at the December meeting took over effective control of the CPI from P. C. Joshi, its General Secretary, was clearly convinced that the formation of the Cominform and Zhdanov's report to it heralded Moscow's return to the "left" strategy.7 That he should have remained unaware of the uncertainty actually prevailing on this point in Moscow is not surprising when it is considered that he had only Zhdanov's vague and largely inapplicable language to guide him. He must have felt sure, however, that he was expected to discard the "right" strategy, and, like many of the CPI leaders, he was in any case inclined to be "leftist" and had never known any but the "left" alternative to the "right" strategy. Even when Zhukov's application of the Zhdanov thesis to the colonial areas must have become known in India, Ranadive, like Balabushevich and Dyakov in Moscow, persisted in giving that thesis a "left" interpretation, probably not so much in reliance on those two Soviet experts and in defiance of the Zhukov view as simply in ignorance of the difference between them. Moscow apparently neither supported nor rebuked Ranadive, who is likely to have emerged as the CPI's new leader more because he had long been the outstanding "left" rival of Joshi, whose "right" policy was discredited by the Zhdanov speech, than as a result of any direct intervention by Moscow.

The switch from "right" to "left" in the CPI's line through the little-publicized December 1947 resolution was publicly confirmed at its Second Congress held in February-March 1948 in Calcutta. This, following immediately upon the Moscow-sponsored Southeast Asia Youth Conference in the same city, has often mistakenly been regarded as the turning point in CPI strategy. The Second Congress formally replaced Joshi by Ranadive as General Secretary and adopted a Political Thesis (Bombay, 1949) which was essentially an elaboration of the December resolution, though somewhat more explicit on the use of violent methods and making even clearer Ranadive's fantastic belief, derived from Zhdanov's two-camp thesis, in the imminent outbreak of revolution in India and throughout the world. It is only on the basis of this expectation that CPI policy during the next two years can be understood.

There was a striking absence of comment in Moscow on the Second CPI Congress. Throughout 1948 the international Communist leaders neither clearly approved nor disapproved of the CPI's new "left" strategy. As yet the new strategy as it had been advocated by Zhukov and earlier developed by Mao had not become dominant in Moscow, for Balabushevich and others continued to include statements in their writings implying adherence to the "left" strategy. While they now sometimes confined their condemnations to the "big" bourgeoisie, thus approaching Zhukov's line, they did not, like the latter, take the crucial step of including any section of the bourgeoisie among the forces led by the Communist Party.

Thus again left without clear direction from Moscow but no doubt in the belief that it enjoyed Soviet support, the CPI, following its Second Congress, embarked on a policy of violent strikes and terrorism, especially in large urban areas. This resulted in heavy loss of support for the Party and growing dissatisfaction and factionalism within it, but this merely led Ranadive to engage in further adventures and intra-Party repression, bringing the CPI close to complete collapse. Only the Telengana uprising was fairly successful during this period. It was led by the Andhra provincial committee of the CPI, which had long enjoyed considerable autonomy and now, because of its independence and the relative success of its program of rural violence, became the most dangerous rival of Ranadive whose policy of urban violence was failing. The ensuing conflict between the two reflected in an extreme fashion the uncertainty between the "left" and the new strategy then prevailing in Moscow.

In June 1948 the Andhra Committee submitted an anti-Ranadive document to the CPI Politburo advocating adherence to the new strategy.8 Basing themselves completely on the Chinese Communist example, as was only natural for Asian Communists engaged in armed clashes and leaning on peasant support mobilized through a program of agrarian reform, the Andhra Communists stood for both the specifically Chinese elements of that strategy (rural guerrilla warfare and chief reliance on the peasantry) as well as its essential elements (concentration on imperialism and feudalism, rather than capitalism, as the main enemies; a "democratic" but not "socialist" revolution in the near future; and the inclusion of a section of the bourgeoisie as well as the "middle" and even the "rich" peasantry in the united front "from below").

Just as the Andhra document had gone well beyond Zhukov's analysis in its adherence to the new strategy, so Ranadive's reply to this challenge, formulated at a Politburo session lasting from September to December 1948 and published in the form of four statements appearing between January and July 1949,9 reached a point in its uncompromising advocacy of the "left" strategy never approached by Dyakov and Balabushevich in Moscow. The native Indian bourgeoisie, rather than foreign imperialism and feudalism, was now depicted as the main enemy, not only in the cities but (in the role of the rich peasantry) even in the countryside. The united front "from below" against the Congress, therefore, could be based only on the urban and rural proletariat and poor peasantry and could include some middle peasant and petty bourgeois elements, but in no case any part of the bourgeoisie or the rich peasantry. Correspondingly, the coming revolution would be a "socialist" one. The issue between the "left" and the new strategy was thus joined in the conflict between Ranadive and the Andhra Communists and the differences between the two were clearly brought out, while their similarities -- the reliance on the approach of the united front "from below" against the Congress and the possible use of violent tactics -- also emerged by implication from the discussion.

However, Ranadive went further and, no doubt, in order to ingratiate himself in Moscow, where he apparently expected an early shake-up of the international Communist leadership, he sharply accused various unnamed "advanced" Communist parties for having been guilty of "revisionism" since the end of World War II. By this he meant all forms of cooperation with bourgeois elements, whether "from above" with bourgeois parties, as applied in the "right" strategy in Western Europe: in the immediate postwar years, or "from below", as used in the new strategy of Mao Tse-tung in China against the Kuomintang (hitherto considered the principal bourgeois party) -- two very different approaches which, as a doctrinaire "leftist," Ranadive was unable to distinguish. Finally, in the last of the four Politburo statements, Ranadive went even beyond this point and, relying heavily on Zhdanov's Cominform speech, attacked Mao Tse-tung by name, ridiculing the assertion that he was an authoritative source of Marxism, mentioning him in one breath with Tito and Browder and describing some of his passages advocating the promotion of capitalism as "in contradiction to the world understanding of the Communist Parties," "horrifying" and "reactionary and counterrevolutionary."10 Whether Ranadive actually enjoyed the support in Moscow as he, the leader of a small and unsuccessful Communist Party, must have believed before he would have made such an attack on the powerful Mao and whether Moscow or one faction in Moscow, such as one representing the now dead Zhdanov, was opposed to Mao and approved of or even encouraged Ranadive's step are questions on which it is fascinating to speculate11 but on which no evidence is available.

Whatever Moscow's attitude toward Mao, it was Ranadive's misfortune that by the time he had reached the high point of his opposition to the new strategy Moscow had finally, after two years of uncertainty, given its support to the latter. Quite apart from any influence the Chinese Communist victories may have had, the Soviet leaders no doubt realized that the "left" line, by regarding capitalism as an enemy, unduly limited the range of the Communists' potential supporters in their cold war with the United States to the so-called exploited classes and thus entailed the serious danger that each Communist party would concentrate on the bourgeoisie in its own country as its main enemy, to that extent ignoring Moscow's main enemy, the United States. It is even possible that both Ranadive's practical course in 1948 and 1949 and his theoretical formulations in his conflict with the Andhra Committee contributed to this realization in Moscow and to the recognition that the new strategy with its willingness to cooperate with virtually everyone regardless of class against its main enemy, foreign imperialism, was far better suited to the needs of the Soviet Union's anti-American foreign policy.

The adoption of the new strategy in Moscow was marked by two concurrent events in June 1949. One was the publication in Pravda of a pamphlet (Internationalism and Nationalism12) by the foremost Chinese Communist theoretician, Liu Shao-chi, written as early as November 1948. The cause of the delay in its appearance in Moscow could hardly have been its main contents, which, being directed against Tito, would have been welcomed earlier, but is likely to have been a passage at its very end in which the Communists in colonial and semi-colonial countries, including India, were expressly told that they would be committing "a grave mistake" if they did not "enter into an anti-imperialist alliance with that section of the national bourgeoisie which is still opposing imperialism." At the very time when this vigorous directive to the Asian Communist parties to adopt the new strategy appeared in the pages of Pravda, a meeting of the Soviet Academy of Sciences on the colonial movement was taking place. It differed sharply from the similar meeting held two years earlier. The reports delivered (as well as another set of reports presented to the Academy later in 1949 13) showed that not only Zhukov but also the former champions of the "left" strategy, Balabushevich and Dyakov, who dealt specifically with India, favored the inclusion of some bourgeois elements in the united front "from below," though it is interesting to note how much more grudgingly and reluctantly the latter two took this step than Zhukov and some other Soviet writers represented in these reports. During the months following June 1949, the Cominform journal and Pravda also showed clearly that the new strategy now had Moscow's approval by featuring pronouncements of Mao Tse-tung and Chu Teh advocating it.

A showdown between Moscow and the CPI now became inevitable. The situation, in which Ranadive, who had always thought of himself as a faithful follower of Moscow, was now hopelessly doomed, did not lack elements of drama. The end, however, was not to come for several months. Ranadive seems to have long remained unaware of the most recent change in Moscow; in fact his most violent attack on the new strategy appeared in print a month after Moscow had publicly embraced it. In November 1949 Moscow utilized the meeting in Peking of one of its international front organizations, the World Federation of Trade Unions, to dramatize and publicize to the Asian Communist parties the fact that Moscow's and Peking's views on Communist strategy now coincided. Sounding the keynote of this meeting and, indeed, of the subsequent history of Asian Communism, Liu Shao-chi in a speech reprinted in the Cominform journal of December 30, 1949, directed the various colonial Communist parties in the most unequivocal language to take "the path" of China and of Mao Tse-tung and defined this path as union of the "working class ... with all other classes, parties, groups, organizations and individuals who are willing to oppose the oppression of imperialism" in a broad united front, but as requiring "armed struggle" only "wherever and whenever possible." That India was not considered a country where armed struggle was possible (a fact of crucial importance in the next phase of the CPI's history) was implied in the Manifesto issued by the Peking meeting and printed in the Cominform journal of January 6, 1950, and had already been suggested earlier in Zhukov's reports to the Academy of Sciences.

Even the clear call of the Peking WFTU Conference was ignored by the CPI. Ranadive seemed too blindly convinced of the correctness of his "left" strategy to understand any but the most direct orders from Moscow and was, in any case, by now too deeply committed to that strategy to be able to give it up without admitting that his intra-Party rivals had been right and thus losing power to them. More immediate intervention by Moscow finally came in the form of an editorial in the Cominform journal of January 27, 1950, entitled "Mighty Advance of National Liberation Movement in the Colonial and Dependent Countries," telling the CPI to take the Chinese "path" of forming the broadest united front with all anti-imperialist classes and elements, but again pointedly omitting India from the list of countries where the use of armed violence was appropriate. The editorial thus did substantially no more than repeat the message of the WFTU Conference, but it was addressed directly to the CPl and, above all, it emanated not from Peking, which Ranadive despised as a source of Communist strategy, but from the very Cominform on which he had placed his main reliance. Thus publicly abandoned by Moscow, Ranadive's fate was sealed and his Party rivals began to close in on him, which they had not ventured to do (in spite of the utter failure of his policies) as long as he could claim Moscow's support. Still he sought desperately to cling to his authority. Instead of issuing a statement of abject "self-criticism" called for by Communist ritual in this situation, Ranadive, writing in the February-March issue of Communist, hailed the Cominform editorial but subtly reinterpreted it to justify and even praise his own strategy. It is not clear whether this was the result of his inability to understand the import of the editorial or a desperate gamble to gain time, but in any case Moscow did not accept his statement and, by remaining silent, allowed the Andhra faction to press its attack against the hated Ranadive. On April 6 Ranadive issued one more statement, far more self-critical than its predecessor but apparently still an attempt to remain in power. This, too, failed to regain Moscow's support and, at a meeting held in May and June 1950, the Central Committee "reconstituted" itself and the Politburo and replaced Ranadive as General Secretary with Rajeshwar Rao, the leader of the Andhra faction. A CPI Central Committee statement (appearing half a year after the Cominform editorial had initiated the shake-up) announcing the change in both leadership and policy was published in Pravda and Izvestia of July 23, 1950,14 and was thus given Moscow's stamp of approval.

The leadership of the CPI had fallen into the Andhra Communists' hands because they had long been the foremost champions of the new strategy in India and the only well-organized opposition to Ranadive within the Party and not because they had been selected by Moscow for their clear understanding of what was desired there. In a series of statements published after their assumption of the CPI's leadership in the July-August 1950 issue of Communist, they not only mercilessly criticized Ranadive's "left" strategy and restated the fundamentals of their own new strategy but also made it clear that, deeply committed as they were to the type of peasant guerrilla warfare they had been carrying on in Telengana, they (wrongly) interpreted Moscow's and Peking's references to the "Chinese path" as including the specific Chinese Communist tactics of such warfare, as well as the essential four-class element of the new strategy. The continuation by the Andhra leaders of Ranadive's emphasis on violent methods, though their focus was now being shifted entirely from urban to rural areas, led to further disintegration of a Party already on the brink of ruin and to what a September 1950 circular of their Politburo called "a state of semi-paralysation."15

Three months earlier, a Chinese Communist statement, "An Armed People Opposes Armed Counterrevolution," had appeared in the Peking People's Daily of June 16, 1950, and in English in People's China of July 1, 1950, thus being available to the CPI. After referring to the WPTU Conference and the Cominform editorial and specifically to the Indian Communists, it had pointed out that "armed struggle ... can by no means be conducted in any colony or semi-colony at any time without the necessary conditions and preparations." However, this pointed warning was ignored by the CPI, for even its Andhra leadership, though it took the Chinese Communists as its example, looked to Moscow alone for directives. Yet Moscow, in spite of the admittedly disastrous situation within the CPI, seemed again in no hurry to provide specific guidance on how its order to adopt the new strategy was to be implemented.

Finally, in December 1950, such guidance arrived in the form of an open letter, published in the CPI's Cross Roads on January 19, 1951, from R. Palme Dutt, the British Communist leader of Indian descent who had in years past often served as Moscow's voice for the CPI. The Party was now told in some detail that its "present paramount task is ... the building of the peace movement and the broad democratic front." Here it was also suggested that Nehru's neutralism, again and again "unmasked" by the CPI since December 1947 as subservience to "Anglo-American imperialism," was "a very important development." In the same month the CPI's Central Committee met to enlarge itself and reconstitute the Politburo by adding adherents of the new strategy in its peaceful form to its violent followers in the Andhra faction. While it was openly admitted that "differences on vital tactical issues have yet to be resolved" (Cross Roads, December 29, 1950, p. 5), a number of statements made at this meeting and in subsequent months emphasized the themes struck in Dutt's letter and thus underlined the ascendancy of the peaceful over the violent form of the new strategy in the CPI. This shift in policy, unlike the earlier ones from Joshi's "right" to Ranadive's "left" and from the "left" to Rajeshwar Rao's new strategy, was a gradual one. The leaders of both factions shared power, an arrangement inconceivable in the earlier cases, which indicates that the differences between violent and peaceful tactics, though more spectacular, are far less fundamental than those among the three strategies of Communism.

In April 1951, the CPI leadership published a new Party program (reprinted in the Cominform journal of May 11, 1951) which, in strict accordance with the new Communist strategy, did not demand a united front with the Congress as had the "right" strategy, and explicitly rejected the antibourgeois revolution called for by the "left" line. It called for replacing "the present anti-democratic and anti-popu1ar Government by a new Government of People's Democracy, created on the basis of a coalition of all democratic anti-feudal and anti-imperialist forces in the country." The May Day Manifesto of the same period defined these forces as consisting of Socialists who oppose their anti-Communist leaders, "other Leftists, honest Congressmen, and above all, the lakhs of workers, peasants, middle classes, intellectuals, non-monopoly capitalists and other progressives,"16 a perfect statement of the new strategy's united front "from below" uniting workers and capitalists. By April 1951, however, the Party's leadership was also sufficiently consolidated around the Moscow line not merely to reaffirm its adherence to the new strategy but also to issue an authoritative Statement of Policy17 on the tactics by which this strategy was to be achieved. Both Ranadive's urban insurrections and the Andhra Communists' guerrilla warfare were specifically rejected and "the correct path" was now proclaimed, "a path which we do not and cannot name as either Russian or Chinese." The view which Moscow and Peking had been hinting at for well over a year, that armed violence on the Chinese model was not applicable in India, was then elaborated at some length, though the use of violence in principle in the more distant future was not rejected.18 The immediate tasks of the Party were again described as the formation of the broadest possible united front against the Congress and Socialist Parties and the building up of the peace movement, both of which were intimately related to the essential element of the new strategy, its "four-class" appeal.

The Statement of Policy marked the defeat of the violent application of the new strategy as advocated by the Andhra faction, a fact confirmed when the Central Committee in the following month replaced Rajeshwar Rao with Ajoy Ghosh as the Party's new leader and when, after the failure of efforts at negotiations with the government, the Party in October 1951 nevertheless called off the fighting in Telengana.19 The changes in leadership and the Party's documents setting forth the new line were finally ratified by an All- India Conference of the CPI in October 1951 and, in a Politburo statement appearing in the Cominform journal of November 2, 1951, were hailed as settling all differences and disputes that had torn the Party during the preceding years. Though harmony was now by no means established among the CPI leaders, the Party leadership has, ever since 1951, been firmly settled on the new strategy in its peaceful form and, most important for its stability since then, was for the first time in at least two (and possibly four) years successful in comprehending Moscow's wishes concerning both strategy and its violent or peaceful execution.

That the CPI's strategy has, since 1951, enjoyed Moscow's approval is indicated by the publication in the Cominform and Soviet press of CPI documents, which had been strikingly absent during the preceding years, and of five major articles (within two and a half years) in the Cominform journal by Ghosh, the present General Secretary,20 an honor not once accorded to Ranadive or Rajeshwar Rao. Palme Dutt and several Soviet writers also praised the CPI's new line in the year following its adoption. Finally, at a session of the Soviet Academy of Sciences in November 1951, which offered the clearest indication up to that time of the Soviet view of Communist strategy in underdeveloped countries in general and in India in particular,21 both Zhukov and Balabushevich very clearly distinguished between the essential four-class element of the new strategy, which was applicable everywhere, and its specific Chinese element of armed violence, which was applicable in some countries but was explicitly and vigorously rejected for India.

Since this agreement on the new strategy in its peaceful form was reached in 1951, only differences on tactics have remained to plague the CPI leadership. A full discussion of these would be beyond the scope of this article,22 but some of the difficulties the CPI has faced in executing the new strategy during the past four years may be briefly noted. One of the most pervasive of these seems to be "sectarianism," i.e. the reluctance of party members to cooperate with the many non-Communist elements who must be drawn into the united front of the new strategy. Another is the tendency to form that united front primarily from above by entering into alliances with various relatively small "left" parties, in which the CPI's identity is in danger of being submerged, rather than from below by winning members away from the major anti-Communist parties, the Congress and the Socialists. Still another problem, related to that of sectarianism, is the continued hostility on the part of wide circles in the CPI toward the broad non-party peace movement which the Communists have sought to build up since 1951.

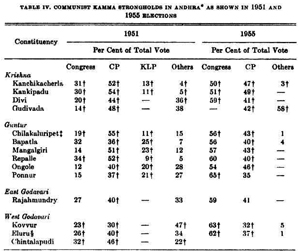

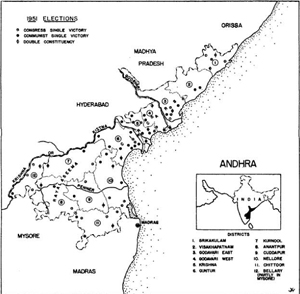

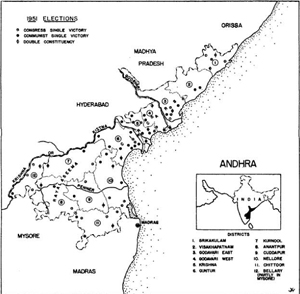

All these difficulties were aired at the CPI's Third Congress held in January 1954 in Madurai. The last mentioned issue appeared in the form of a conflict over whether Britain or the United States was to be regarded as the main enemy.23 Those who hold the primarily anti-British view, notably the Andhra Communists, are also the ones who wish to emphasize the "national liberation movement" and to concentrate on building a strong Party and who, being "sectarians," tend to look down on the peace movement where they are expected to cooperate with non-Communists. The anti-American attitude, on the other hand, is closely associated with emphasis on the peace movement and would definitely seem to be closer to Moscow's desires. Why, then, could the conflict between the two not be resolved clearly in favor of the latter, but was in fact treated with the greatest caution by the leadership? The answer is suggested by Ghosh's reports on the Third Congress, when he said that the anti-American position would lead to "full support" of the Nehru government, which the CPI seems to regard as basically pro-British and anti-American. Such a step, the CPI leadership recognized, would involve another shift in strategy back to the "right" line of a united front "from above" with the Congress. Moscow, however, does not (at any rate not yet) seem to regard the Nehru government as sufficiently anti-American and pro-Soviet to warrant CPI efforts at cooperation with it. Obviously, Nehru's neutralist foreign policy poses a dilemma for the Indian Communists.24 This was recently confirmed when their Central Committee, perhaps in response to an editorial in Pravda praising Nehru, blamed the CPI's disastrous defeat in the Andhra elections of February 1955 primarily on the Party's failure to emphasize sufficiently the "important part India was playing in recent times in the international arena in favor of world peace and against imperialist warmongers."25

The new strategy of international Communism is essentially the Soviet Union's reaction to the cold war, an adjustment of Communist policy to a situation where the major parties in a country, both bourgeois and labor, are relatively pro-American and anti-Soviet and yet where the Communists want to unite all the classes represented by these parties against the United States. This situation prevails throughout most of the non-Soviet world, and the new strategy has in recent years been applied throughout it, not only in the underdeveloped areas of Asia and Latin America, but even in the West. In countries, however, where the governments and some major parties are neutralists, difficulties of the type just mentioned as besetting the CPI may arise. Whether Moscow and the Communist parties will be able to adjust to such a situation remains to be seen. Guatemala under the Arbenz regime and Indonesia, where the united front "from below" was given up for that "from above" with anti-American parties, point one way, whereas Burma, where the Communists have for years fought a civil war against a neutralist government, suggests another direction.

_______________

Notes:

1. This article is based on research done by the author at the Center for International Studies, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in 1953-43. Its complete and documented results are available in his CENIS paper, shortly to be published as a book, “Moscow and the Communist Party of India: A Study in the Postwar Evolution of Communist Strategy,” Cambridge, Mass., 1954. The general concept of Communist strategy on which this case study is based is set forth in the author’s article, “The New Strategy of International Communism,” to appear in the June or September 1955 issue of “The American Political Science Review.” The author wishes to express his deep appreciation of the advice he has received from Morris Watnick and Bernard Morris.

2. For a short history of the CPI during the prewar and war periods, with many quotations from Communist documents illustrating the Party’s attitude, see Madhu Limaye, “Communist Part, Facts and Fiction,” Hyderabad: Chetana Prakashan, 1951, pp. 18-50. For a fuller treatment of these periods, also useful for its quotations and notes, see M.R. Masani, “The Communist Party of India, A Short History,” London: Derek Verschoyle; New York: Macmillan, 1954, chapters 1-5.

3. See the draft and final versions of the CPI’s election manifesto, “For a Free and Happy India,” “World News and Views,” December 1, 1945, p. 391, and “Final Battle for Indian Freedom,” ibid., March 10, 1946, p. 78.

4. For a very useful analysis, with many quotations of Soviet statements on India during the postwar years, see Gene D. Overstreet, “The Soviet View of India, 1945-1948,” Columbia University (unpublished M.A. thesis in Political Science), 1953.

5. Akademia Nauk SSSR, Uchenye zapiski tikhookcanskogo institute, Moscow, 1949, Vol. II.

6. E. Zhukov, “K polozheniiu v Indii,” Morovoe Khoziaystvo I Mirovaya Politika, July 1947.

7. See P.C. Joshi, “Views,” Calcutta, May 1950, p. 27. This first and only issue of Joshi’s periodical is an extremely revealing collection of anti-Ranadive statements made by him after his ouster from the CPI.

8. The text of this document has not been available to the author but its main features can be reconstructed from “Struggle for People’s Democracy and Socialism – Some Questions of Strategy and Tactics,” “Communist,” Bombay, June-July 1949, pp. 21-89; and from “Statement of Editorial Board of “Communist” on Anti-Leninist Criticism of Comrade Mao Tse-tung,” ibid., July-August 1950, pp. 6-35.

9. “On People’s Democracy,” Ibid., January 1949, pp. 1-12; “On the Agrarian Question in India,” ibid., pp. 13-53; “Struggle Against Revisionism Today in the Light of Lenin’s Teachings,” ibid., February 1949, pp. 53-66; “Struggle for People’s Democracy and Socialism,” loc. cit.

10. “Struggle for People’s Democracy and Socialism,” loc. cit., pp. 77-79. It is fascinating to note that Ranadive also attacked Maoism for placing its entire reliance on the Communist Party instead of the working class, ibid., p. 88, partly quoted in Robert C. North, “Moscow and the Chinese Communists,” Stanford, 1953, p. 242. He thus puts his finger on a real weak spot (from the point of view of Marxian theory) of Maoism. What Ranadive remained unaware of is that he was here attacking the very basis of Leninism, that it was Lenin, not Mao, who first “deviated” from Marx on this fundamental point and that Maoism, being an adjustment of Marxism to an even more undeveloped country than Tsarist Russia, is but Leninism in a more developed form. Both Leninism and Maoism seek to obscure their perversion of Marxism by defining the working class, in a most un-Marxian manner, in terms of its adherence to Communist ideology, thus generally identifying the Party and the class, a trick which Ranadive by distinguishing between the two very uncautiously laid bare in his attack on Maoism.

11. See Franz Borkenau, “The Chances o a Mao-Stalin Rift,” “Commentary,” August 1952, pp. 117-123; Ruth Fischer, “The Indian Communist Party,” “Far Eastern Survey,” June 1953, pp. 79-84.

12. Pravda, June 7, 8 and 9, 1949, in “Soviet Press Translations,” July 15, 1949, pp. 423-489; also Liu Shao-chi, “Internationalism and Nationalism,” Peking: Foreign Languages Press, no date.

13. “Colonial Peoples’ Struggle for Liberation,” Bombay: People’s Publishing House, 1950; also condensed from Voprosy Ekonomiki, August and September 1949, in “Current Digest of the Soviet Press,” January 3, 1950, pp. 3-10; and “Crisis of the Colonial System, National Liberation Struggle of the Peoples of East Asia,” Reports presented in 1949 to the Pacific Institute of the Academy of Sciences, USSR, Bombay: People’s Publishing House, 1951.

14. “Current Digest of the Soviet Press,” September 9, 1950, p. 31.

15. Quoted in Limaye, op. cit., p. 75.

16. “May Day Manifesto of Communist Party of India,” “Cross Roads,” April 27, 1951, p. 3. A lakh is one hundred thousand.

17. Bombay, 1951; also “Cross Roads,” June 8, 1951, pp. 3, 6, and 16. Most of the important passages are reprinted in “Communist Conspiracy in India,” Democratic Research Service, Bombay: Popular Book Depot, (distributed in the U.S. by the Institute of Pacific Relations, N.Y.) 1954, pp. 20-23.

18. See “Tactical Line,” in “Communist Conspiracy in India, op cit.,” pp. 35-48 and in Masani, op cit., pp. 252-263. This supposedly secret document on which the “Statement of Policy” was based makes the last-mentioned point more frankly but in essence does not differ substantially from the published Policy Statement.

19. “C.P.I. Ready for Negotiated Settlement in Telengana,” “Cross Roads,” June 15, 1951, p. 3; “C.P.I. States Basis for Telengana Settlement,” ibid., July 27, 1951, pp. 1-2; “Congress Game in Telengana,” ibid., August 10, 1951, p. 8; “C.P.I. Advises Stoppage of Partisan Action in Telengana,” ibid., October 24, 1951, pp. 1, 3.

20. On October 19, 1951; March 28, 1952; November 7, 1952; February 5, 1954; May 21, 1954.

21. Izvestia Akademii Nauk SSSR, History and Philosophy Series, Vol. IX, No. 1, January-February 1952, pp. 80-87, in “Current Digest of the Soviet Press,” June 28, 1952, pp. 3-7 and 43; and in “Labour Monthly,” January 1953, pp. 40-46; February 1953, pp. 83-87; March 1953, pp. 139-144.

22. The present divisions of the CPI are well summarized in Marshall Windmiller, “Indian Communism Today,” “Far Eastern Survey,” April 1954, pp. 49-56.

23. “Communist Conspiracy in India,” op. cit., pp. 12-19 and 51-52; Ajoy Ghosh, “On the Work of the Third Congress of the Communist Party o India,” “For a Lasting Peace, for a People’s Democracy!,” February 5, 1954, p. 5; “Political Resolution,” New Delhi: Jayant Bhatt, 1954.

24. See the very interesting discussion of the CPI’s attitude toward Nehru in Madhu Limaye, “Indian Communism: The New Phase,” “Pacific Affairs,” September 1954, pp. 195-215, 205-207 and 212-213.

25. Quoted in A.M. Rosenthal, “Indian Reds Admit Error in Andhra,” New York Times, March 31, 1955. The CPI’s failure to pursue “correct” united front tactics before the election also was criticized by the Central Committee.

Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

Record of Conversations between G.M. Malenkov and M.A. Suslov with the Representatives of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of India

Translated by Vijay Singh.

February 21, 1951

Summary: G.M. Malenkov speaks with representatives of the Indian Communist Party, including [Shripad Amrit] Dange, Ghosh, and Rao. The ICP delegation asks for Soviet advice on party organization and composition. Malenkov responds, warning the ICP to take care not to come off as a Soviet puppet. Malenkov's main suggestion is to determine a firm party line, and publish a singular and clear program for the party, so as to unite disputing factions.

Original Language: Russian

Record of the Discussions of Comrades G.M. Malenkov and M.A. Suslov with the Representatives of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of India Comrades Rao, Dange, Ghosh, and Punnaiah

21 February 1951

Malenkov: We have been informed of your desire to discuss organizational questions with us. As you already are aware, discussions on questions touching on the program of the party will take place in a matter of days.

Rao: Yes, we wish to talk about organizational questions. Our main organizational problems are the following: we must settle the question of the postponement of the congress and the composition of the Central Committee. Comrade Stalin spoke of the need to finish the endless discussions in the party. We consider that the party congress should take place after the determination of the political line. We will need to explain to the party masses why, when the congress has not been held for a significant period already, it has not been fixed in the current period. In our party the opinion exists that the party organs starting from the lowest and ending with the highest must be elected in a democratic way. If we in our own name say that the party congress must be put off, that would probably not carry weight. If, however, we say that this is the advice of the international communist movement, then we may convince the members of the party. Now some words on the second question: the composition of the Central Committee. From the constituents of the current Central Committee, 14 persons are left (in 1949 the Central Committee consisted of 31 persons; in May 1950 there were 9 persons). It is not representative, as only our tendency and the tendency of Ghosh and Dange are represented. Therefore, such a Central Committee cannot guarantee the unity of the party. It seems to me that Joshi must be reinstated to the party. This is necessary in order to guarantee the unity of the party. The question of the entry of Joshi as a part of the central committee would be put up by a significant number of party members. We hold contrary positions to Joshi, but I consider that he must become part of the central committee. Some trends which exist in the provinces are not represented in the central committee. They must be represented. Only thus will we go ahead. I consider that it is necessary to establish regular contact with the CPSU (b) for the benefit of resolving questions which spring up in the course of our daily practical work. In our time, we were given the advice of the CC of the CPSU (b) in 1933. In 1947, the discussion between Dange and Zhdanov took place, but the advice we were then given was half implemented. We found it outrageous that Dange never informed us why this advice was not carried out. We wish to know what advice was given to us [and] how it was sabotaged so that we may get to know particular individuals better. In 1947, one of the Chinese comrades returning from a session of the World Federation of Trade Unions had a discussion with Joshi lasting 6-7 hours, but nothing of this was reported to the Central Committee, and we learned about it only recently.

Malenkov: We can give you advice as to how in principle one should approach the resolution of organizational questions. You must excuse us as we will not manage to give you advice on separate practical problems and details. I wish to remind you that our advice is not obligatory. It may or may not be accepted by you.

It seems to me that for you to cite the advice of the international communist movement, in order to lean upon this advice to justify the postponement of calling the congress of the Communist Party of India, would be incorrect. It is harmful. You will be declared agents of Moscow and this will inflict damage on the communist movement in India.

We always avoid giving the least pretext to dub this or that party an agent of Moscow. Whether the Communist Party of India can cope with such kind of an organizational problem, we think that they can manage it. You will now have a party program. It is an important circumstance. In this is the advantage of the present stage of relations between the CPSU (b) and the Communist Party of India: we will work out the document, the program of the Communist Party of India. This document will lie at the basis of all of the activities of the Communist Party of India. It will facilitate the activity of the Communist Party of India.

The most reliable and tested members of the Communist Party must come into the Central Committee. The central committee must not represent an amalgam of the representatives of all of the existing tendencies in the party. You asked how some individual comrades should be dealt with. First of all, Joshi. Once you have your program, the Central Committee as currently constituted will determine all activity which will rally the entire party. In constituting the Central Committee, the reliable and tested comrades must be included who have the ability to lead the party in the direction indicated by the program. Whether Joshi proceeds from this point of view is for you to consider. If I am not mistaken, there were previous discussions on this theme. It is necessary to verify in what measure Joshi will fulfill the will and program of the party.

Contact between the Communist Party of India and the CPSU (b) is necessary. It has been useful. To that measure, in whatever way the Central Committee of the Communist Party of India might carry out this contact, it is necessary to do it. We will assist [you in] this. Maybe we can think of establishing an organization of specialists in radio relations for this. We might be able to render some sort of assistance for this purpose.

Dange: At the time of the discussion in 1947, such a proposal was brought up but was left unimplemented.

Ghosh: I agree that, having obtained advice on principles on organizational questions, we will limit it to this and must leave all the affairs of organizational relations for the Indian Communist Party.

I wish to ask you, so far as members of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of India who are permanently situated in East Pakistan are concerned, should they be members of the Central Committee.

Malenkov: To have relations with the workers of East Pakistan is helpful. To have organizational relations, i.e., to have them as members of the Central Committee, is not obligatory.

Dange: Since my meeting with Cde. Zhdanov has been referred to here, I must inform you that after my return from Moscow I made a detailed report on this meeting to the Politburo of our party -– Comrades Ranadive, Joshi, Adhikari. There is no document of this for the reason that I was working in conditions of complete conspiracy and it was not possible to distribute my report in the form of a written document then as that would have been dangerous. I communicated all the questions including the question of radio relations. In February 1948 the Second Congress of the party took place and in April I was put into prison and cut off from party life.

Malenkov: In past discussions we touched upon the question of instituting candidate membership in the party. This would help to raise the quality of the party and draw in tried and tested people, not enlarging the membership of the party too much but rather placing emphasis on the quality of persons taken into the party.

Dange: Yes, we thought over this suggestion and consider it feasible.

Punnaiah: After our program is published, it will be clear that we strongly made a mess-up of many questions. It will be clear that we were incorrect on many questions. For example, on the question of understanding the Chinese path of development. After the publication of the program, let there appear leading articles in the press of the fraternal communist parties morally supporting the program and the Central Committee. This would be a great help to us. I asked you also to bring clarity to some questions which I have on the problem of partisan warfare in India.

Malenkov: You will bring out the program of the party in the name of the Central Committee which will unite people on the basis of that program. Following from this, the activists will unite around the program. I think that the publication of the program of the Communist Party of India will determine our relations to them. The position of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of India would be very strong. And then that fact–whatever were the earlier points of view -- acquires a secondary significance once the program comes out, uniting the Central Committee. Each one of you would be recognized as one who steadfastly contributed to the party program. This will end confusion and unite the Central Committee on the basis of the program.

Ghosh: I fully agree with this. Once the publication of our program is a fact, that will be fully sufficient.

Malenkov: Do the comrades still have any questions for us? I want to inform the comrades that if they wish to get to the bottom of difficult material problems, then they might want to take into consideration that at the present time there exists the ‘International foundation to help the left workers’ organizations.’ We can render help in accordance with this.

Rao: We will think over this and inform you.

Dange: We need to open the struggle against the influence of bourgeois ideology over the masses, particularly on the questions of the history and philosophy of India. Our youth find bourgeois psychology on these questions acceptable. Maybe the Academy of Sciences can take upon itself this specialized work in order to render us some assistance. We require English translations of books appearing here on India and, in particular, we wish to receive the Chronological Notebooks of Marx on India. We have only two books devoted to the history of India: the book of Dyakov[i] and my book on the ancient history of India. If we might find the corresponding forms to relate the scientific work in India with the work of the Academy of Sciences, that would be a great help for us.

I wish to return to the request to have a meeting with the chairman of the All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions, Comrade Kuznetsov, for a discussion on trade union questions.

Cde. Malenkov said that the request of Comrade Dange would be fulfilled.

[Taken down by] V. Grigor’yan 22.II.51

_______________

Notes:

[ i] A. M. Diakov was a leading Soviet scholar and political commentator on India since the 1930s. In 1948, his book The Nationality Question and English Imperialism in India found opportunities for revolutionary activity among India’s nationalities. His over-eagerness was attacked in 1952, and Diakov opted for self-criticism.

Translated by Vijay Singh.

February 21, 1951

Summary: G.M. Malenkov speaks with representatives of the Indian Communist Party, including [Shripad Amrit] Dange, Ghosh, and Rao. The ICP delegation asks for Soviet advice on party organization and composition. Malenkov responds, warning the ICP to take care not to come off as a Soviet puppet. Malenkov's main suggestion is to determine a firm party line, and publish a singular and clear program for the party, so as to unite disputing factions.

Original Language: Russian

Record of the Discussions of Comrades G.M. Malenkov and M.A. Suslov with the Representatives of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of India Comrades Rao, Dange, Ghosh, and Punnaiah

21 February 1951

Malenkov: We have been informed of your desire to discuss organizational questions with us. As you already are aware, discussions on questions touching on the program of the party will take place in a matter of days.

Rao: Yes, we wish to talk about organizational questions. Our main organizational problems are the following: we must settle the question of the postponement of the congress and the composition of the Central Committee. Comrade Stalin spoke of the need to finish the endless discussions in the party. We consider that the party congress should take place after the determination of the political line. We will need to explain to the party masses why, when the congress has not been held for a significant period already, it has not been fixed in the current period. In our party the opinion exists that the party organs starting from the lowest and ending with the highest must be elected in a democratic way. If we in our own name say that the party congress must be put off, that would probably not carry weight. If, however, we say that this is the advice of the international communist movement, then we may convince the members of the party. Now some words on the second question: the composition of the Central Committee. From the constituents of the current Central Committee, 14 persons are left (in 1949 the Central Committee consisted of 31 persons; in May 1950 there were 9 persons). It is not representative, as only our tendency and the tendency of Ghosh and Dange are represented. Therefore, such a Central Committee cannot guarantee the unity of the party. It seems to me that Joshi must be reinstated to the party. This is necessary in order to guarantee the unity of the party. The question of the entry of Joshi as a part of the central committee would be put up by a significant number of party members. We hold contrary positions to Joshi, but I consider that he must become part of the central committee. Some trends which exist in the provinces are not represented in the central committee. They must be represented. Only thus will we go ahead. I consider that it is necessary to establish regular contact with the CPSU (b) for the benefit of resolving questions which spring up in the course of our daily practical work. In our time, we were given the advice of the CC of the CPSU (b) in 1933. In 1947, the discussion between Dange and Zhdanov took place, but the advice we were then given was half implemented. We found it outrageous that Dange never informed us why this advice was not carried out. We wish to know what advice was given to us [and] how it was sabotaged so that we may get to know particular individuals better. In 1947, one of the Chinese comrades returning from a session of the World Federation of Trade Unions had a discussion with Joshi lasting 6-7 hours, but nothing of this was reported to the Central Committee, and we learned about it only recently.

Malenkov: We can give you advice as to how in principle one should approach the resolution of organizational questions. You must excuse us as we will not manage to give you advice on separate practical problems and details. I wish to remind you that our advice is not obligatory. It may or may not be accepted by you.

It seems to me that for you to cite the advice of the international communist movement, in order to lean upon this advice to justify the postponement of calling the congress of the Communist Party of India, would be incorrect. It is harmful. You will be declared agents of Moscow and this will inflict damage on the communist movement in India.

We always avoid giving the least pretext to dub this or that party an agent of Moscow. Whether the Communist Party of India can cope with such kind of an organizational problem, we think that they can manage it. You will now have a party program. It is an important circumstance. In this is the advantage of the present stage of relations between the CPSU (b) and the Communist Party of India: we will work out the document, the program of the Communist Party of India. This document will lie at the basis of all of the activities of the Communist Party of India. It will facilitate the activity of the Communist Party of India.

The most reliable and tested members of the Communist Party must come into the Central Committee. The central committee must not represent an amalgam of the representatives of all of the existing tendencies in the party. You asked how some individual comrades should be dealt with. First of all, Joshi. Once you have your program, the Central Committee as currently constituted will determine all activity which will rally the entire party. In constituting the Central Committee, the reliable and tested comrades must be included who have the ability to lead the party in the direction indicated by the program. Whether Joshi proceeds from this point of view is for you to consider. If I am not mistaken, there were previous discussions on this theme. It is necessary to verify in what measure Joshi will fulfill the will and program of the party.

Contact between the Communist Party of India and the CPSU (b) is necessary. It has been useful. To that measure, in whatever way the Central Committee of the Communist Party of India might carry out this contact, it is necessary to do it. We will assist [you in] this. Maybe we can think of establishing an organization of specialists in radio relations for this. We might be able to render some sort of assistance for this purpose.

Dange: At the time of the discussion in 1947, such a proposal was brought up but was left unimplemented.

Ghosh: I agree that, having obtained advice on principles on organizational questions, we will limit it to this and must leave all the affairs of organizational relations for the Indian Communist Party.

I wish to ask you, so far as members of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of India who are permanently situated in East Pakistan are concerned, should they be members of the Central Committee.

Malenkov: To have relations with the workers of East Pakistan is helpful. To have organizational relations, i.e., to have them as members of the Central Committee, is not obligatory.

Dange: Since my meeting with Cde. Zhdanov has been referred to here, I must inform you that after my return from Moscow I made a detailed report on this meeting to the Politburo of our party -– Comrades Ranadive, Joshi, Adhikari. There is no document of this for the reason that I was working in conditions of complete conspiracy and it was not possible to distribute my report in the form of a written document then as that would have been dangerous. I communicated all the questions including the question of radio relations. In February 1948 the Second Congress of the party took place and in April I was put into prison and cut off from party life.

Malenkov: In past discussions we touched upon the question of instituting candidate membership in the party. This would help to raise the quality of the party and draw in tried and tested people, not enlarging the membership of the party too much but rather placing emphasis on the quality of persons taken into the party.

Dange: Yes, we thought over this suggestion and consider it feasible.

Punnaiah: After our program is published, it will be clear that we strongly made a mess-up of many questions. It will be clear that we were incorrect on many questions. For example, on the question of understanding the Chinese path of development. After the publication of the program, let there appear leading articles in the press of the fraternal communist parties morally supporting the program and the Central Committee. This would be a great help to us. I asked you also to bring clarity to some questions which I have on the problem of partisan warfare in India.

Malenkov: You will bring out the program of the party in the name of the Central Committee which will unite people on the basis of that program. Following from this, the activists will unite around the program. I think that the publication of the program of the Communist Party of India will determine our relations to them. The position of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of India would be very strong. And then that fact–whatever were the earlier points of view -- acquires a secondary significance once the program comes out, uniting the Central Committee. Each one of you would be recognized as one who steadfastly contributed to the party program. This will end confusion and unite the Central Committee on the basis of the program.

Ghosh: I fully agree with this. Once the publication of our program is a fact, that will be fully sufficient.

Malenkov: Do the comrades still have any questions for us? I want to inform the comrades that if they wish to get to the bottom of difficult material problems, then they might want to take into consideration that at the present time there exists the ‘International foundation to help the left workers’ organizations.’ We can render help in accordance with this.

Rao: We will think over this and inform you.

Dange: We need to open the struggle against the influence of bourgeois ideology over the masses, particularly on the questions of the history and philosophy of India. Our youth find bourgeois psychology on these questions acceptable. Maybe the Academy of Sciences can take upon itself this specialized work in order to render us some assistance. We require English translations of books appearing here on India and, in particular, we wish to receive the Chronological Notebooks of Marx on India. We have only two books devoted to the history of India: the book of Dyakov[i] and my book on the ancient history of India. If we might find the corresponding forms to relate the scientific work in India with the work of the Academy of Sciences, that would be a great help for us.

I wish to return to the request to have a meeting with the chairman of the All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions, Comrade Kuznetsov, for a discussion on trade union questions.

Cde. Malenkov said that the request of Comrade Dange would be fulfilled.

[Taken down by] V. Grigor’yan 22.II.51

_______________

Notes:

[ i] A. M. Diakov was a leading Soviet scholar and political commentator on India since the 1930s. In 1948, his book The Nationality Question and English Imperialism in India found opportunities for revolutionary activity among India’s nationalities. His over-eagerness was attacked in 1952, and Diakov opted for self-criticism.

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 40042

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

Record of a Conversation between Stalin and representatives of the Indian Communist Party

February 09, 1951

by Wilson Center Digital Archive

Translated by Gary Goldberg.

Summary: Meeting in Moscow between Stalin and Indian Communist Party representatives C. Rajeswara Rao, S. A. [Shripad Amrit] Dange, A. K. Ghosh, and [M. Basava] Punnaiah. Stalin responded to a series of prepared questions from the representatives.

Original Language: Russian

RECORD OF A CONVERSATION BETWEEN I. V. STALIN and representatives of the Indian Communist Party CC, Cdes. [C. Rajeswara] Rao, [S.A.] [Shripad Amrit] Dange, [A. K.] Ghosh, and [M. Basava] Punnaiah

9 February 1951

Cde. Stalin: I have received your questions. I will reply to them and then state some of my own views.

Possibly it will seem strange to you that we discuss everything in the evening. We are busy in the daytime. We are working. We get off work at 6 P.M.

Possibly it will seem strange to you that the conversation lasts a long time but unfortunately we cannot perform our mission otherwise. Our CC has entrusted us with meeting with you personally to help your Party with advice. We don’t know your Party and your people well. We take this mission very seriously. As soon as we took it upon ourselves to give advice we thereby took the moral responsibility for your Party upon ourselves and we cannot give frivolous advice. We wanted to acquaint ourselves with the materials and with you, and then give advice.

It might seem strange to you that we asked you a number of questions and have almost made an interrogation. But our position is such that we could not do otherwise. Documents do not give a complete idea and therefore we resorted to such a method. This is a very unpleasant business but nothing can be done about it. The situation demands it. Let’s move to the substance of the matter.

You ask: how should the impending revolution in India be evaluated?

We Russians view this revolution as primarily agrarian. This means the liquidation of feudal property and the division of land between peasants into their personal property. This means the liquidation of feudal private property for the sake of establishing private peasant property. As you see, there is nothing socialist here. We do not think that India is on the threshold of a socialist revolution. This is also the Chinese way which they talk about everywhere, that is, an agrarian revolution, anti-feudal without any confiscation and nationalization of the property of the national bourgeoisie. This is a bourgeois-democratic revolution or the first stage of a people’s democratic revolution. The people’s democratic revolution which started before China in the countries of Eastern Europe has two stages. The first stage is an agrarian revolution or agrarian reform, if you wish. The countries of the people’s democracies in Eastern Europe went through this stage in the first year after the war. China is in this first stage right now. India is approaching this stage. The second stage of a people’s democratic revolution, as it has manifested itself in Eastern Europe, consists of moving from an agrarian revolution to the expropriation of the national bourgeoisie. This is already the start of a socialist revolution. Factories, mills, and banks have been nationalized and handed over to the state in all the people’s democratic countries of Europe. China is still far from this second stage. This stage is also far from India or India is far from this stage.

They have been talking there in India about the lead article of the Cominform newspaper concerning the Chinese way of unleashing a revolution. This lead article was prompted by the articles and speeches of [Balachandra Trimbak] Ranadive, who thought that India was on the path to a socialist revolution. We Russian Communists think that this is a very dangerous thesis and have decided to speak out against it, pointing out that India is experiencing the Chinese path, that is, the first stage of a people’s democratic revolution. This means that you will have to create your own revolutionary front this way: rouse the entire peasantry and kulaks against the feudal lords, and rouse the entire peasantry so that the feudal lords feel isolated. The public and all progressive strata of the national bourgeoisie need to be roused against British imperialism in order to isolate the bloc of British imperialists and national bourgeoisie. You are accustomed to saying that all imperialists need to be expelled at one stroke, all of them, both British and American. The front cannot be created this way. The sharp edge of the nationwide front needs to be directed against British imperialism. Let the other imperialists, including the Americans, think that you aren’t concerned with them. This is necessary so that all the imperialists are not united against you by your actions and in order to sow discord among them. Well, but if the American imperialists get into the fight themselves then it will be necessary to turn the united national front of India against them, too.

Ghosh: It’s not clear to me why only against British imperialism at a time when a struggle is going on in the entire world against American imperialism, which is considered the sharp edge of the antidemocratic camp?

Cde. Stalin: Very simply, a united national front against Britain is for national independence from Britain, not from America. This is your specific national character. India is semi-liberated from whom? From Britain, not from America. India is in a Commonwealth of Nations not with America, but with Britain. The military and other specialists in your army are not Americans, but Britons. These are the historical facts, and there’s no getting around them. I want to say that the Party should not pile every task on itself, the task of fighting the imperialists of the entire world. [Only] one goal needs to be set, liberation from British imperialism. This is India’s national goal. The same thing about the feudal lords. Of course, the kulaks are enemies. But it is foolish to fight both the kulaks and feudal lords. It is foolish to pile two burdens on yourself, fighting kulaks and fighting feudal lords. A front needs to be created so that not you, but the enemy, is isolated. This is, so to speak, a tactic which makes the struggle of the Communist Party easier. Not a single person, if he is reasonable, would be willing to take all burdens on himself. Only one goal needs to be taken on, the elimination of feudalism, a remnant of British rule. Isolate the feudal lords, liquidate the feudal lords, and smash British imperialism, without at the same time touching the other imperialists. If this works, it will make matters easier. Well, if the American imperialists butt in, then the struggle against them will have to be waged, but the people will know that it is they who attacked, not you. The Americans’ turn will come, of course, and the kulaks, too. But then each in his own turn.

Ghosh: Now it is clear to me.

Dange: Will this not interfere with waging agitprop work against the American imperialists and fighting them?

Cde. Stalin: Of course not. They are enemies of the people and they need to be fought.

Dange: I asked this question so that no one would interpret the task of struggling against American imperialism in an opportunistic way.

Cde. Stalin: The enemy needs to be isolated cleverly. Propose a resolution not against American imperialists, but against British imperialists. If the Americans butt in, then that is another matter.

Rao: Among the kulaks there is a small group which engages in feudal exploitation: they lease land and are usurers. They usually side with the landlords.

Cde. Stalin: This doesn’t mean anything. In comparison with the great overall goal of liquidating the feudal lords, this is a particular case. In your propaganda you need to speak out against the feudal lords, but not against prosperous peasants. But you yourselves ought not incite kulaks into an alliance with feudal lords. It’s not necessary to create an alliance for the feudal lords. The kulak has great influence in the village and peasants think that the kulak became someone thanks to his great abilities, etc. The kulak need not be given the ability to defeat the peasants. Are your feudal lords nobles?

Rao: Yes.

Cde. Stalin: Peasants do not love nobles. You need to latch onto this in order not to give the feudal lords an opportunity to have allies among the peasants.

Punnaiah: We have confusion among ourselves concerning the issue of the national bourgeoisie. What is meant by the national bourgeoisie?