Caste and the Andhra Communists

by Selig S. Harrison

University of California (Berkeley)

American Political Science Review, Volume 50, Issue 2, pp. 378-404

June 1956

The primary raw material of Communist power in economically less developed regions of the world is neither the landless peasant with outstretched rice bowl nor the intellectual in search of a cause. Even more basic than these frequently summoned symbols, the realpolitik of social tensions determines political events where economic scarcity aggravates the particularisms dividing man from man.

This contention gains strength from a study of Communist fortunes in a representative Asian setting. With little or no industrial economy to ease population density and underemployment, Andhra State on the southeast coast of India bears the familiar marks of Asian poverty. Here has emerged the most successful regional Communist movement in India. Yet the explanation for Andhra Communist strength does not lie in economic factors. The postwar decade in Andhra demonstrates that social factors can relegate even unusually powerful economic factors to a position of secondary importance.

A comparative analysis spanning three elections in Andhra shows that Communist success has depended primarily on the effective manipulation of social tensions. In Andhra these tensions have been twofold: the rivalry between two rising peasant proprietor caste groups, and the struggle of all Andhra, a Telugu-speaking region of 20,507,801 people, to win linguistic identity as a separate province within the Indian Union. Communist candidates have won their margins of victory most often when they have been able to exploit allegiance to caste and to language region. They have made the most of economic despair, signs of decay in the governing Congress party, and the reflected glory of international communism, but these alone do not get to the bottom of the Communist roots in Andhra soil.

The present study seeks to establish the crucial importance of caste manipulation as a source of Andhra Communist strength.1 This is not to say that Communists monopolize exploitation of caste. Inevitably the institution of caste, so peculiarly integral to all Hindu social organization, pervades the entire political system in predominantly Hindu India. Whether caste in India lends itself more readily to political manipulation than do social factors elsewhere has not yet been explored. But Hindu caste discipline clearly wields a measure of political influence in India that cries for serious study. While the non-Hindu who presumes to assess this influence cannot escape his own limitations as an outsider, he sees at the same time that those in the fold who could speak with greater authority rarely do so by the very fact of their personal position.

As an example of Hindu caste discipline in political motion, the postwar decade in Andhra merits special attention. Caste has played so fundamental a role during this period that this examination becomes in effect a case history in the impact of caste on India's representative institutions.

The accident of three free elections within a decade in Andhra -- 1946, 1951, and 1955 -- makes Andhra a uniquely convenient unit of study. The first of these elections came only a year before independence. The British Indian regime conducted a limited franchise ballot to choose provincial legislatures which, in turn, named the constitution-writers of India's first Constituent Assembly. By 1951, Prime Minister Nehru's government had launched nationwide direct elections on a basis of general adult franchise to select new members both of the lower house of the Indian Parliament and of state assemblies. The 1951 balloting set a relatively stable political pattern throughout India, with the notable exceptions of Andhra, Travancore-Cochin, and the Patiala and East Punjab States Union (PEPSU).

In the case of Andhra, the legislators elected in 1951 were seated alongside deputies speaking Tamil, Malayalam, and Kannada, in the legislature of multilingual Madras State, a sprawling political Babel carved out by British mapmakers with little regard to south India's cultural differences. It was only after Potti Sriramulu, a prominent Gandhian advocate of provincial autonomy, fasted unto death in 1952 that the Nehru government demarcated Andhra as a separate state. When the new unit was inaugurated in October, 1953, the 160 Telugu members of the Madras legislature, including a 41-member Communist bloc, became the new Andhra legislature. A Congress cabinet took office, but factionalism within and Communist harassment from the outside brought its collapse on a no-confidence motion by November, 1954. New elections had to be conducted in February, 1955, the third in less than ten years.

For all Andhra political groups, this decade of near-deadlock was a rigorous exercise. Where else in Asia has a major Communist bid for power faced so intensive a testing process at the polls? Moreover, the checkered course of Andhra Communist strategy during the period under study enhances the significance of this examination. For the primacy of caste and language manipulation in Andhra Communist success has persisted through the gamut of a wartime united front, four bloody guerrilla years, and the present parliamentary phase of Indian communism.

By focusing on caste and language it is possible to discover why the Andhra Communists, while successively increasing their popular vote from 258,974 (on a limited franchise in 1946) to 1,208,656 (1951) to 2,695,562 (1955), were able to win a significant number of seats in the legislature only in 1951. To add to this seeming discrepancy, not only did the popular vote increase -- it increased without disturbing the localized concentration of Communist power.

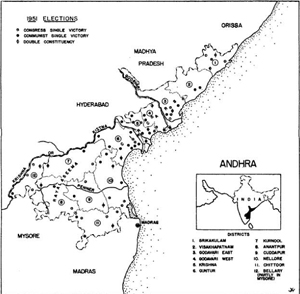

1951 ELECTIONS

In all three elections Andhra. communism demonstrated its greatest strength in the fertile rice delta where the Krishna and Godavari rivers empty into the Bay of Bengal. Contrary to the theme that poverty above all breeds communism, arid Rayalaseema in west Andhra has consistently failed to produce a significant Communist response.

I. "KULAK PETTAMDARS"

To find the keys to this puzzling situation it is necessary first to establish the major caste contours of the Andhra political landscape. As the Indian government's recent report on rural credit warned:

It is necessary to place the operational picture against the social background of rural India. This is more important than almost anything else for a true understanding of the working of rural credit, cooperative, governmental, or other, just as indeed it is also indispensable for the proper appraisal of the effects of any particular measure of policy or legislation or administration as they shape themselves, or sometimes fail to take shape at all, in the actualities of the Indian village.2

In the case of the Andhra Communists, the effective use of caste does not arise full-blown out of a bottomless tactical armory but rather out of the caste homogeneity of the Andhra Communist leadership itself. Since the founding of the Andhra Communist party in 1934, the party leadership has been the property of a single subcaste, the Kamma landlords, who dominate the Krishna-Godavari delta.3 This fact carries enormous importance in view of the rising influence of the Kammas in Andhra life. The war and postwar years were a boom period for the Kamma farmers,4 who own an estimated 80 per cent of the fertile delta land.5 High prices for both food and cash crops made many Indian peasant proprietor castes newly rich, but for the Kammas, presiding over land as productive as any in all India, the boom was especially potent.

Kamma funds have made the Andhra party better able to support itself than any other regional arm of Indian communism. In fair political weather or foul a virile, expensively produced Communist press in Andhra's Telugu language has been kept alive by a Kamma publisher, Katragadda Rajagopal Rao,'6 whose family also operates one of India's largest Virginia tobacco plantations and virtually monopolizes the fertilizer market in Andhra.7 As "the people who count"8 in the villages of the delta districts, even relatively modest Kamma landholders have been in a position to put decisive influence on the side of the Communist party.9

Aruna Asaf Ali, a member of the Indian Communist Central Committee, has said that "a distinguishing feature of the Andhra party is its social content. The rural intelligentsia (numerically stronger and politically a great deal more mature than in the rest of India) has provided the party with a leadership that knows its mind and is unmistakably competent."10 Three wealthy Kamma intellectuals have maintained for at least the past 15 years key control of the Andhra Communist party: party secretary Chandrasekhar Rao, former national Indian Communist party secretary Rajeshwar Rao, and M. Basava Punniah, a member of the Indian Communist Central Committee.11 As a result, an Andhra Communist dissident has coined the epithet kulak pettamdar to attack the Andhra leadership, coupling the Russian word for rich peasant with the Telugu word for head of a caste or tribe.12

In sharp contrast to Kamma control or the Communist party, stands the power of the rival landowning Reddi caste in the Congress party.13 This posture of political competition between the two caste groups is only a modern recurrence of an historic pattern dating back to the fourteenth century14. In the past century15 the rivalry has sharpened to the point where the Kammas have felt themselves an excluded "out" group in social and political life -- a sociological fact which has figured prominently in the strategy of both major parties in the elections under study.

Kamma lore nurtures the image of a once-proud warrior clan reduced by Reddi chicanery to its present peasant status. Reddi duplicity, recounted by Kamma historian K. Bhavaiah Choudary, was first apparent in 1323 A.D. at the downfall of Andhra's Kakatiya dynasty. Reciting voluminous records to prove that Kammas dominated the Kakatiya court, Choudary suggests that the Reddis, also influential militarists at the lime, struck a deal at Kamma expense with the Moslem conquerors of the Kakatiya regime. The Kammas lost their noble rank and were forced into farming.

In his research Coudary frankly has an axe to grind: he seeks to establish Kamma claims to Kshatriya (warrior) rank, second in the traditional Hindu caste hierarchy, rather than their present Sat-Sudra status.16 His main outline of Kamma and Reddi history, however, does not differ essentially from the consensus of more disinterested scholars.17 Both Kammas and Reddis were probably warriors in the service of the early Andhra kings. Later they became farmers, some feudal overlords and others small peasant proprietors who to this day take part in the cultivation of their land. Between them they dominated rural Andhra, leaving Brahmans beyond the pale of economic power in the countryside.

For five centuries the Kammas have centered in the four mid-Andhra delta districts, which Choudary says were once known as "Kamma Rashtra" or "Kamma Land." The 1921 census18 shows 600,679 Kammas congregated in the delta districts, with another 560,305 scattered in other Andhra districts and in pockets in neighboring Tamil territory.19 The extent of Kamma dominance in the delta is exemplified in Guntur district, where all other peasant proprietor castes together totaled 149,308, less than half the Kamma figure.

Thc Reddis20 gravitated to the five Rayalaseema districts of west Andhra. Here Kammas are in the minority; in Cuddapah, for example, Reddis numbered 211,558 to 20,171 Kammas, and in Kurnool, Reddis were 121,032 to 14,313 Kammas. Today in popular Telugu parlance the region is called "Reddiseema."

This geographical separation of the two powerful castes had a tribal logic; in anyone local area, only one or the other caste group with its patriarch could be dominant. When British tax-collectors came onto the scene, they formalized the status quo, extending the sway of leading landholders in each caste over vast zamindari estates. Fourteen Kamma zamindars became the biggest estate owners in the delta country.

Despite their wealth, the Kammas and Reddis as a village-centered rural gentry lagged behind the traditionally education-minded Brahmans in gaining the English literacy that was the entry to political leadership in the early years of the independence movement. For example, the 1921 census showed that out of 79,740 literate Kammas, only 2,672 were able to read English, while out of 159,730 literate Telugu Brahmans, as many all 46,498 were literate in English.21

Choudary explains this in the following way:

Shorn of their principalities, commanding officer's posts, and choudariships, Kammas had to content themselves with the lot of peasants and husbandmen. Learning only Telugu, they looked after their ryotwari [holdings]. Only about 1900 A.D., Kammas awakened to the fact that without English education they cannot better their position. The few educated Kammas who joined government service had to struggle hard to come up due to lack of patronage and the opposition of Brahman vested interests.22

It was inevitable that Kamma-Reddi competition would increase with the educational advancement of the two castes, and that the Brahman politicians who controlled the Andhra Congress party would gradually lose their actual -- if not titular -- party control to others exercising greater local power in Andhra. This is precisely what happened between 1934 and World War II. Both Kammas and Reddis, pushing forward with the anti-Brahman movement that swept all South India, supported the Andhra branch of the short-lived Justice party.23 Then Reddi power lodged itself in the Congress behind a Brahman facade at the same time that a clique of young Kamma intellectuals was founding the Andhra Communist party. Choudary notes that Kamma youth were attracted by "the Communist Party, with its slogans of social equality," but he does not seek to explain why the party in Andhra became "predominated by Kammas" rather than Reddis.24

The circumstances explaining the polarization of Kamma-Reddi warfare on a Communist-Congress basis deserve further study. The consensus in Andhra points to geographical accident: the Kammas happened to be in the delta. There political activity of every stripe had always been greater than in Rayalascema. From the beginning of the independence movement Gandhian Congress leaders found their liveliest Andhra response in the delta rice trading towns of Vijayawada and Guntur, centers of the region's intellectual and political ferment. Thus, just as the then Brahman-dominated Congress drew its leadership from the delta, so the challenge to this leadership emerged within the strongest non-Brahman caste group in the delta. In addition, in the delta's legions of landless laborers there was the grist of a mass movement plain to any young Marxist intellectual looking for a cause.

The young Reddi intelligentsia in the Rayalaseema hinterlands was politically quiescent by comparison with the Kammas. The young Reddi who did desire a political career could best seek it in the Congress, where his caste group, gravitating almost by default, had cornered the market on the bulk of the party's non-Brahman patronage. Some young Reddi leaders were a part of the Communist party from its inception, but they have always been outnumbered by Kammas. Only one has held his own in the party hierarchy, Puchalapalli Sundarayya, whose real name is Puchalapalli Sundar Rama Reddi.25 He is in a position comparable to that of the Kamma Congress veteran, N. G. Ranga, a nationally prominent Congress figure and another notable exception to the rule of caste politics in Andhra. Both of these politically displaced persons enjoy wide personal popularity, but both strike discordant notes within the otherwise relatively homogeneous leadership cliques of their respective parties.

II. THE ROLE OF LANDLESS LABOR

Against this historical backdrop it is now possible to examine the course of political events surrounding the 1946, 1951, and 1955 elections in Andhra in an effort to explain the consistent concentration of the Communist popular vote in the delta as well as its special potency in 1951.

In 1946, Andhra was the only region in India where the Communists felt strong enough to enter a bloc of candidates across one large contiguous group of constituencies against the candidates of the Congress-recognized champion of independence at a time when India remained under foreign domination. In Bengal, Malabar, and parts of north India, where the Communist party was also an election factor, Communist entries were pinpointed in scattered centers of industrial or farm labor, but in Andhra they were massed solidly over the delta. Of the 62 constituencies in areas now forming Andhra,26 the Communists contested 29, all virtually side by side. Twenty-four were located in Krishna, Guntur, East and West Godavari districts, the delta belt commonly called the "Circars."27 This concentration in the delta was no momentary accident of tactics but a reflection of the basic character of Andhra communism. The pattern of 1946 remains the pattern of 1955.

TABLE I. LOCATION OF COMMUNIST POWER IN ANDHRA, AS SHOWN IN 1946, 1951, AND 1955 ELECTIONS

Year / Votes Cast in Four Delta Districts:* % of Total Votes Cast / Communist Votes Cast in Four Delta Districts: % of Total Communist Vote / Communist Candidates Contesting in Four Delta Districts: % of Total Communist Candidates

1946 / 55.1 / 94.7 / 89.2

1951 / 54.3 / 85.5 / 72.2

1955 / 56.2 / 72.8 / 57.4

* The four Andhra districts in the Krishna-Godavari delta are Krishna, Guntur, East Godavari, and West Godavari.

With Communist candidates almost exclusively centered in the delta in 1946 (see Table I), it was not surprising that most Communist votes were recorded there. Even in 1955, however, with only 57.4 per cent of the Communist candidates running in the delta districts, 72.8 per cent of the Communist vote still went to these delta contestants. In 1951, 31 of the 41 successful Communist candidates were in delta constituencies; in 1955, 11 of 15. In all three elections, the delta has provided an average of 55 per cent of Andhra's total vote.

View this concentration in the delta alongside the failure of the Communists in 1955 to win more than 15 seats in a 196-member chamber28 -- at the same time that they were increasing their share of the popular vote from18.6 to 31.2 per cent. Congress quarters reason hopefully29 that the increased vote resulted naturally from the greater number of Communist, candidates in 1955 (169 out of a total 560) than in 1951 (61 out of 614). Yet this explanation ignores the fact that the Communists retained their high proportion of the vote in their delta heartland. While their ambitious "shotgun" strategy helps explain why the Communists won comparatively few seats in 1955, other factors must be found to explain the consistent concentration of the Communist popular vote as well as its special potency in 1951.

Certainly one feature distinguishing the delta scene from other parts of Andhra is the high population density -- especially the high percentage of landless laborers. Density runs from 900 to 1200 persons per square mile in the delta, as compared with 316 in the rest of Andhra. Thirty-seven per cent of the total agricultural population in the delta is landless labor, a concentration second only to Malabar District on the West Indian coast.30

Andhra Communist leaders have from the outset attempted to organize the Adi-Andhras, an untouchable subcaste comprising the bulk of the region's landless migrants.31 Their success has been conceded by Communist leaders outside Andhra who granted that "the organized strength of agricultural workers in Andhra is by far the biggest in any province."32 The likelihood that the votes of landless laborers have been a bulwark to Communist strength gains further support from an analysis of the concentration of Communist votes alongside the irrigation map of the delta. The same extensively irrigated delta rice country which, as a focus of fanning, has dense settlements of landless labor, such as Tenalii, Gudivada, Bapatla, and Bandar taluks (subdivisions) in Krishna District, is also the site of consistently high Communist voting.33 After the 1951 elections, the Congress publicly acknowledged that Communist "canalization" of agricultural labor votes had played an important part in the election.24 There is no evidence to suggest that this factor was absent in 1955. On the contrary, the Communists themselves claim that "the moot oppressed and exploited strata of the people in the rural areas, the agricultural workers and poorest peasants, stood firmly by the party."35 Independent press comment has accepted this as a fact.36

In 1946, however, the Communists could not have derived much benefit from this source of strength. Franchise limitations excluded all but 13 per cent of the population. In addition to a literacy requirement, only registered landholders owning, in addition to their homes, immovable property valued at the rupee equivalent of $10 or more were permitted to vote.37 Therefore, landless farm laborers were unable to take part in the election.

In any case, the support of landless labor would not explain the two subsequent elections. To be sure, six of the 31 seats won by the delta Communists in 1951 were reserved for scheduled castes (untouchables). These seats, by their very nature, hang on the support of landless labor. In addition, these six reserved seats were in double-member constituencies in which the Communists also won the six non-reserved seats. In these double constituencies both general and scheduled caste voters can vote twice, each influencing the outcome in both seats; landless labor thus clearly played a role in the six non-reserved seats in these double-member constituencies. In the remaining 19 of the 1951 Communist victories, landless labor votes must also have been an important prop to Communist candidates. But if dependable landless labor support alone explains Andhra communism, why then could the Communists not win as many seats in 1955 as in 1951?

It is the contention of this study that Communist victory in 1951 stemmed from a timely confluence of events, favorable to the manipulation of social tensions, which did not recur in 1955. In 1951 the movement to carve a separate Andhra State out of Madras had reached a high emotional pitch. The Communists surcharged the election atmosphere with propaganda keyed to Telugu patriotism, while in 1955, with Andhra State a reality, the Congress could make Indian nationalism the issue. Furthermore, at the same time that they were exploiting Telugu solidarity in 1951, the Communists made the most of a bitterly tense moment in Andhra's caste rivalries -- a crisis which the Congress was able to surmount in time for 1955.

III. THE 1946 ELECTIONS

At the end of the war, with the polarization of Andhra politics on caste-party lines almost complete, the Kamma Congress leader, N. G. Ranga, was on the far fringes of the Andhra Congress power structure. Inside, a personal rivalry raged between two prominent Telugu Brahman politicians: Pattabhi Sitaramayya, official historian of the Indian National Congress, and Tanguturu Prakasam, "Lion of Andhra," a mass idol, who won a legendary reputation in the independence movement when he bared his chest before British police, daring them to shoot. Sitaramayyu typified the Brahman facade behind which Reddi power made its appearance. In 1946 he held firmly onto the Andhra Congress machinery, though Prakasam maneuvered many of his own choices into election nominations. N.G. Ranga was, then, part independent operator, part Prakasam satellite.

Frankly building his political career on a Kamma base, Ranga had articulated a "peasant socialist" theory38 gingered by Western class slogans but boiling down in concrete terms to a defense of peasant proprietorship as opposed to land nationalization. In Andhra he organized a compact political striking force, bent on increasing Kamma influence in the Congress while at the same time fighting the Communists by reciting the story of Stalin and the peasant. In 1946, however, with Congress activity only beginning to regain momentum after the war, there was little time to put a striking force into action before the elections. Relatively few Kammas won Congress nomination and election, even in Kamma strongholds (see Tables II and III).

The Kamma Communist leaders were in a more favorable position. During the war the Andhra Communists fattened handsomely on the official patronage accorded All-India communism for support of the defense effort. The Congress, demanding freedom first, protested when Britain decided that India was at war. Thus, while Congress leaders spent the war in British jails, Communist leaders not only had a clear field to organize but actually had government support to popularize rationing and talk down strikes.39 In parts of India where the Communist movement had gained a foothold before the war, this favored position presented a rare opportunity for rapid expansion. The Andhra Communists could take full advantage of the situation. Besides the wealth and influence of their Kamma leaders, they had capitalized as much as any regional Communist party from the prewar united front with the Congress Socialist party, walking off with almost the entire Andhra Socialist organization in 1939.40

TABLE II. NUMBER OF CANDIDATES BY MAJOR CASTES IN ANDHRA DELTA DISTRICTS, IN 1946, 1951, AND 1955 ELECTIONS

Year / Communist Kamma / Communist Reddi / Communist Brahman / Communist Other / Congress Kamma / Congress Reddi / Congress Brahman / Congress Other

1946 / 9 -- / 1 / 1 / 4 / 3 / 4 / 7

1951 / 22 / 2 / 3 / 15 / 17 / 7 / 2 / 20

1955 / 32 / 4 / 6 / 24 / 28 / 7 / 7 / 25

Note: Constituencies reserved for scheduled castes and tribes have been omitted. In the case of 1946, when certain constituencies were also reserved for urban as distinct from rural voters, and on the basis of labor union membership, religion, and sex, these figures apply only to general rural constituencies.

TABLE III. NUMBER OF ELECTED LEGISLATORS BY MAJOR CASTES IN ANDHRA DELTA DISTRICTS IN 1946, 1951, AND 1955 ELECTIONS

Year / Communist Kamma / Communist Reddi / Communist Brahman / Communist Other / Congress Kamma / Congress Reddi / Congress Brahman / Congress Other

1946 / -- / -- / -- / -- / 4 / 3 / 4 / 7

1951 / 14 / 2 / 3 / 6 / 3 / 3 / -- / 4

1955 / 1 / 2 / 3 / 3 / 24 / 7 / 7 / 25

Note: Constituencies reserved for scheduled castes and tribes have been omitted. In the case of 1946, when certain constituencies were also reserved for urban as distinct from rural voters, and on the basis of labor union membership, religion, and sex, these figures apply only to general rural constituencies.

The Andhra Communists waged a vigorous campaign in the 1946 elections, putting their major effort into Kamma strongholds. Because the sole successful Communist contestant won in a labor stronghold,41 the dominantly rural nature of the Communist effort in 1946 has been overshadowed. Of the 24 delta seats for which the Communists contested, 17 were entirely in rural areas. Of these 17, six were reserved seats for scheduled castes. In each of the 11 remaining "general rural" constituencies, the per cent of the vote polled by the Communists was surprisingly high -- ranging from a low of 11.5 to a high of 31.9, with the median falling just above 20.42 When the franchise property restriction in 1946 is kept in mind, this figure assumes its proper importance. These were not to any substantial degree the votes of agricultural labor. Rather they were votes drawn from the general landed caste Hindu population in the countryside and from propertied voters in small rural centers.

Here a caste analysis of candidates highlights the Kamma base of the Communist leadership, Omitting the xix constituencies set apart for scheduled castes, a caste breakdown of the 11 Communist caste Hindu entrants shows nine Kammas, while of 18 caste Hindu Congress entrants for rural seats in the four delta districts only four were Kammas (Table II).

IV. THE KAMMAS AND MAO'S "NEW DEMOCRACY"

After the 1946 elections, events in India led quickly to the final withdrawal of British rule and the establishment of the new Nehru government. The Indian Communist party, caught in the wartime united front spirit of world communism, was swearing its love for Jawaharlal Nehru as a leftist force in the Congress when the Cominform made its celebrated switch to a terrorist line in Asia in late 1947. Party secretary P. C. Joshi became the scapegoot, and a new insurrectionist strategy was launched under the leadership of B. T. Ranadive. In different parts of India this strategy took different forms. Acid bombs were hurled in the streets of Calcutta as Ranadive talked of urban proletarian uprisings. But in Andhra revolutionary form then distinctive in Indian Communist experience was taking shape. It combined in a paradoxical fashion the power of the Kammas in the countryside with the land hunger of the migrant untouchables in the delta and in neighboring Telengana, the Telugu-speaking southeast corner or Hyderabad State.

This was the so-called Telengana movement, organized along standard Communist guerrilla lines with wholesale land redistribution and parallel village governments. Clusters of villages in the delta and nearly all of Warangal and Nalgonda districts in Hyderahad went under Communist control from 1948 through 1950. Andhra and Telengana Communist leaders directed a two-way offensive, north into Telengana and south into the delta, from a 40-village base or operations in Munagala Jungle in northwest Krishna District.42 Communist squads raided villages by night, police battalions by day. When Indian Army troops conducted their 1948 "police action" against the Nizam of Hyderabad, they stayed on in Warangal and Nalgonda to drive the Communists out. It took them until 1951 to restore normal local government.

In all the tumult in the delta, most Kammas with their valuable paddy lands went unscathed. So long as the middling-rich farmers, who make up the bulk of the caste, stayed above the battle, they were classified in Communist strategy as "neutralized."44 This was outright deviation, not only from the Ranadive line, which saw all landowners as equally villainous, but also from the Moscow-Zdhanov line decreeing unequivocal guerrilla offensives throughout Asia. B. T. Ranadive, attacking the Andhra Secretariat, publicly charged that in Andhra Communist ranks "it is the rural intellectuals, sons of rich peasants and middle peasants, that preponderate in important positions. The party politically based itself on the vacillating politics of the middle peasants and allowed itself to be influenced even by rich peasant ideology." He contrasted Andhra's "wrong social base" with the working class base of the Tamihnad party and the "poor peasant" base in Kerala.45

The Andhra Communists had made no secret of their "rich peasant" policy within the party. They explicitly declared themselves on this point in a 1948 program report for the Indian Communist Politburo which stressed two major tactical rules of thumb:

1. In delta areas the pressure of population would be heavy, and as such slogans should be raised for the distribution of lands belonging to rich ryots among poor peasants and laborers ...

2. Propaganda should be carried on to convince the ryots about the just demands of the workers, and we should also effect compromises with such of those ryots who would follow with us. Assurance should be given that we should not touch the lands of rich ryots.46

B.T. Ranadive singled out for special attack another statement of this position in a 1948 Andhra Secretariat document discussing tactics toward government rice procurement for rationing:

In the matter of procurement of paddy, the Secretariat believes that it is possible to neutralize the rich peasants as the government plan goes against the rich peasantry also. Though the rich peasantry as a class is not standing firmly in the fight, it is parting with paddy with dissatisfaction.

This, Ranadive charged, "constitutes the real practical gist of the document, a program of class collaboration in rural areas, of bowing down before the rich peasant."47

Ranadive and the Andhra Secretariat waged unabashed open warfare that may have reflected a larger struggle in world communism. For then, in mid- 1949, Mao Tse-tung did not yet control the Chinese mainland. Soviet policy still belabored Mao for his "New Democracy" with its expansive welcome to "patriotic" capitalists and rich peasants. The Andhra document specifically justified its "rich peasant" policies by pointing to Mao. But, Ranadive declared, Mao's "horrifying" departures from accepted Stalinist dogma "are such that no Communist party can accept them; they are in contradiction to the world understanding of the Communist parties." Ranadive scolded the Andhra comrades, who "should have thought ten times before making such a formulation."48

John Kautsky has pieced together intricate details of international Communist publications during the period of the Andhra-Ranadive exchange to show that in their controversy they "reflect in an extreme fashion the uncertainty between the 'left' and 'Maoist' views then prevailing in Moscow." Kautsky, describing the disorganized state of Indian communism, also notes the "peculiar internal cohesion and individual character" which makes the Andhra party a striking exception. "As a result, while other regional CPI organizations were at Ranadive's mercy, the Andhra Committee seems to ha\'e remained relatively immune from his interference."49

By January, 1950, the Cominform journal had endorsed the "path taken by the Chinese people,"50 and by the summer of 1950 the Indian Communists were apologizing profusely to Mao.51 They praised "New Democracy" as a model for India to follow, and replaced B.T. Ranadive with the Kamma Andhra Communist leader Chandra Rajeshwar Rao, whose family rice plantation sprawls over 290 acres of fertile delta land.

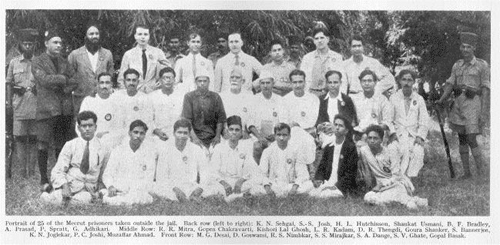

V. COMMUNIST CHANGE OF FRONT FOR THE ELECTIONS

National Indian Communist policy under Rajeshwar Rao's leadership proceeded to misread the Cominform editorial by "assuming that it had been asked to pursue the Chinese path by adopting armed struggle."52 The Telengana struggle was thus stepped up at the very moment when the Nehru government was bearing down on the movement with all its military might. By the Spring of 1951, the superior power of Indian government forces had crushed guerrilla strength in Telengana and the delta. At the same time, a factional split was growing between Rajeshwar Rao and forces led by S.A. Dange, the veteran Bombay Communist labor leader. Dange saw the plainly increasing stability of the Indian political scene and favored participation in the general elections scheduled for the end of the year. To resolve the crisis, Moscow summoned Rajeshwar Rao, his Andhra Kamma colleague Basava Punniah, S.A. Dange, and party stalwart Ajoy K. Ghosh to the Soviet Union to put a Kremlin imprimatur on a peace settlement. The result was the selection of Ajoy Ghosh as party secretary and a new, moderate policy.

As its first peace overture to the government, the Communist party sent out feelers in mid-summer offering to behave as a legal party in exchange for the release of imprisoned detenus, many of whom were the strongest Communist election contenders. At first, the Communist press complained that the government of Hyderabad, where the initial overtures were made, "did not even bother to reply."53 In a Parliament speech August 14, the then Home Minister Chakravarti Rajagopalachari declared that "the party cannot have it both ways, delivering speeches and carrying on other election activities while killing and terrorizing." As late as November 19, the official Congress party organ said that "it would be unprecedented for any government to release men convicted by courts or reasonably detained as enemies of the state.54 Still, in spite of these declarations, the government had an historic last-minute change of heart,55 and released most of the Madras Communist prisoners.

Communist leaders hurried from South Indian jails to their home districts with all the martyr's aura reserved in Indian society for those who suffer privation at the hands of authority. A notification in the Gazette of India dated August 11, 1951 showed 202 communist prisoners in Madras, most of them -- although district by district breakdowns are not available -- from Andhra. Month by month figures in Home Ministry files show the Madras total of its detenus dropping to 86 in December and four by February, 1952. These figures do not include an almost equal number placed on parole at this time and later declared free. Thus, most of the Andhra Communist high command were freed in time to map election strategy for the January balloting. They campaigned feverishly to make up for their late start, well aware that the deep factional crisis then gripping the Congress camp presented a rare opportunity.

VI. 1951 ELECTION SETTING: DECAY IN THE CONGRESS

In the years between the 1946 and 1951 elections, Andhra Congress leaders were locked in a factional war, in which the fortunes of N. G. Ranga went first upward and then to rockbottom. The three-way tussle between Ranga, Pattabhi Sitaramayya, and T. Prakasam was complicated by the multi-lingual nature of Madras politics during that period. To score a point at any given moment, each Andhra faction could reach across not only caste but also regional lines, striking at its rival by aligning with Tamil-speaking factions in the Madras government.

Prakasam, having helped his own lieutenants win Congress seats in the Madras Assembly, could command powerful support in the first skirmish of this period. In the 1946 wrangle for ascendancy in the multi-lingual Madras Legislature Congress party, Prakasam emerged with the prize of the Madras Chief Ministership. But his majority was perilous, for Tamil members of the Assembly had joined in electing him for factional reasons of their own. The ruling Tamil Congress bloc, predominantly non-Brahman, used Prakasam to head off Tamil Brahman Chakravarti Rajagopalachari in his bid for the Chief Ministership. Once succcssfnl, they hurried to hunt allies to replace Prakasam. Caste loyalties on both the Andhra, and the Tamil sides thus vanished at the linguistic border. The 20 Andhra supporters of Brahman Sitaramayya lined up with the non-Brahman Tamil bloc and half of the Malayalam-speaking members of the legislature to unseat Prakasam.

To save his political position in his home territory, Prakasam joined forces with Ranga. Together they took control of the Andhra Congress machinery from Sitaramayya. Ranga won the Andhra Congress presidency, defeating N. Sanjiva Reddi, nominee of the Sitaramayya group.

In the bitter ensuing warfare, both sides aired charges of corruption which the Communist propaganda network carried into remote rural regions. As a result, the Congress leaders soon lost the prestige of their independence movement days. Prakasam followers charged Sitaramayya members of the new Madras regime with trafficking improperly in commercial permits and transport franchises, blackmarketing, and rampant nepotism. They also contended that the Communists enjoyed an unholy alliance with the active leader of Sitaramayya forces in the Madras government, Revenue Minister Kala Venkata Rao. Prakasam cited chapter and verse to allege that Rao, later a national general secretary of the Congress, helped arrange facilities for Red Flag meetings, looked the other way when Communists staged illegal squatter movements, solicited and received Communist help to defeat Prakasam candidates in local elections, and fed anti-Prakasam propaganda to Communist leaders.56

With the Kamma Ranga at the head of the Congress, the opposition to Prakasam and Ranga had strong caste overtones. Reddi forces were a part of the maneuvering that brought Ranga's downfall in April, 1951, when K. Sanjiva Reddi won the Andhra Congress presidency in a close 87-82 decision. Ranga and Prakasam, charging that the Reddi victory hung on "irregularities," walked out of the Congress. Fifty of their sympathizers on the Andhra Congress Committee followed them out of the party. Then came the final blow to Congress unity, a Ranga-Prakasam split. Prakasam announced that his candidates in the general elections would carry the symbol of the new Kisan Mazdoor Praja (Peasants Workers Peoples) party led by Acharya J. B. Kripalani. Ranga formed a Kamma front, the Krishikar Lok (Farmers') party. Therefore, in delta election constituencies where Kamma influence counted, the three-way Congress split meant that at least two Kammas, a Ranga candidate and a nominee of the official Congress, and in many cases other Kammas named bu Prakasam, the Socialist party, or independent local groups, all competed for the campaign support of their wealthy caste fellows.

VII. KAMMA SUPPORT DECISIVE IN 14 COMMUNIST VICTORIES

It was into this inviting situation that the Andhra Communists strode from prison in the fall of 1951. Already on good terms with their Kamma brethren because of their sweet reasonableness during guerrilla days, they warned that the Reddi-dominated Congress was out to get them. Ridiculing Ranga's KLP as a splinter group, they argued that he could not possibly emerge with a majority. The Communists presented themselves as political comers who would soon be able to protect the caste from the citadels of government power.

They had the issues on their side. Not only could they promise five acres and a cow to their traditional supporters, the Adi-Andhra landless laborers; they could also put the Congress on the defensive in the Andhra State issue. Then too, they could inflate popular discontent with food shortages and blackmarketing that grew worse while ruling Congress politicians seemed too busy feuding to take action -- or, as the popular image had it, were knee deep in the trough of corruption.

The Kammas could well have been impressed with the apparently rising star of their caste fellows at the helm of the Communist party. Even the Kamma historian Choudary, outspokenly anti-Communist in his writings, recites with obvious pride a long list of Communist Kamma notables, adding that "many other young Communist legislators have turned out to be able debaters and formidable opponents."57 The Kammas must certainly have considered how desirable it would be to crystallize friendly relations with a revolutionary leadership that had already shown it could be reasonable about whose land was confiscated.

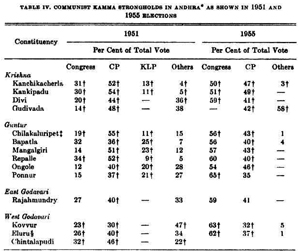

Whatever the understanding58 between the Communists and Kamma patriarchs, a significant section of the Kammas plainly put their funds, influence, and votes behind the Communist Kamma candidates (see Table IV). This factor appears to have tipped the scales in the delta. While the Kamma vote was divided, the share of Kamma support won by the Communists provided the margin of victory in 14 of the 25 delta general constituencies where Communist deputies were elected.59 Three of the six Communist members of the lower house of Parliament elected in 1951 from the delta are Kammas.

The victorious Communist in 1951 drew on the numbers of the landless laborers and protest votes of erstwhile Congress supporters, but powerful Kamma backers gave him in a substantial number of cases even more decisive support -- identification with village-level authority. In a society hardly out of feudalism, this is an intangible which should not be underestimated.

TABLE IV. COMMUNIST KAMMA STRONGHOLDS IN ANDHRA* AS SHOWN IN 1951 AND 1955 ELECTIONS

* Constituencies shown represent all those in which Kamma Communist candidates were elected in 1951. The outcome in the same constituencies is shown in 1955, though it should be borne in mind that new delimitation of constituencies prior to the 1955 elections makes the 1955 constituencies not exactly congruent with the originals under comparison. These constituencies do not necessary represent the sites of greatest Kamma Communist success in 1955. The site of one 1951 Communist victory - Chintalapudi (West Godavari) -- cannot be compared meaningfully with any 1955 constituency.

** Candidates designated in this manner are members of the Kamma subcaste.

*** Renamed Paruchur in 1955.

**** Renamed Denduluru in 1955.

Note: Percentages have been rounded to the nearest decimal. Communist-supported Kamma candidates running on other party tickets or as independents in other constituencies are not included in this analysis in view of the author's inability to gain a precise picture of the division of support in the constituencies concerned. A Communist-supported Kamma won election on the KMP ticket in Narasaropet (Guntur) while a CP-supported candidate lost on the KLP ticket in Tenali (Guntur) and another lost as an independent in Nuzvid (Kirshna).

To a great extent the 1951 results in the delta can be explained simply by the multiplicity of candidates, which enabled the Communists to capitalize on a divided opposition. But it is necessary to examine the nature of this multiplicity. The telling strength of the Communists in this opportunity came from the fact that they were uniquely situated to exploit the divisions in the Kamma camp. Their leaders were Kammas on Kamma ground. Kamma influence is spread evenly enough over the delta so that even in those delta constituencies where non-Kamma Communist candidates were successful, the Kamma population must have played an important role. Furthermore, a glance at the votes polled by the winning Communist Kammas places the factor of multiplicity of candidates in proper perspective. The average Communist Kamma winner polled 44.6 per cent of the votes. In only two constituencies, Eluru and Chintalapudi, did the combined vote of non-Communist Kamma candidates exceed that of the Communist Kamma victor. Even in defeat, Communist Kamma candidates in 1951 polled 33.1 per rent of the votes (see Table V), with their margin of defeat a matter of from one to four percentage points in every instance where the successful candidate was also a Kamma. In sharp contrast, other defeated Communist candidates in the delta polled only an average 22 per cent. Thus the multiplicity of candidates alone cannot explain the large number of Communist victories. The fact that the Communists could compete strongly for the support of the caste group most strategically placed in delta politics was the key to the Communist sweep.

TABLE V. DEFEATED 1951 COMMUNIST KAMMA CANDIDATES IN ANDHRA DELTA DISTRICTS

Constituency / Congress % / CP % / KLP % / Others %

Krishna Kaikalur / 37* / 36* / -- / 27

Guntur Guntur / 24* / 23* / -- / 53

Duggirala / 42 / 38* / 13* / 7

Prathipadu / 26 / 25 / 22* / 27

East Godavari Pamarru / 49* / 46* / -- / 5*

West Godavari Tanuku / 29* / 25* / -- / 46*

* Candidates designated in this manner are members of the Kamma subcaste.

Note: Percentages have been rounded to the nearest decimal. Communist-supported Kamma candidates running on other party tickets or as independents in other constituencies are not included in this analysis.

Outside the delta, too, in constituencies where the Kammas were a potent minority but not dominant, the Communists chose to rely on Kamma support. For example, in the Chittoor parliamentary contest, the Communists unsuccessfully supported a Kamma independent against a Reddi Congress candidate. In Nellore, a coastal district adjacent to the delta where the Kammas have only half the numerical strength of the Reddis,60 the Communists lost out to Congress Reddis in three constituencies where they nominated Kammas.61 Where they won in Nellore it was with Reddi candidates in two solidly Reddi constituencies,62 and with a Brahman in another.63 The two Reddis elected on the Communist ticket in Nellore may owe much of their strength to the prestige of the sole major Communist Reddi leader, Sundarayya, in his home district. Where scattered Reddis were elected in other districts,64 the result appears to have hinged on local and personal factors. The only other Communists elected outside the delta were four Brahmans and one Velama, a petty landlord subcaste.

It was in Nellore that Kamma-Reddi bitterness in 1951 reached its high point in the defeat of the prominent Andhra Congress leader B, Gopala Reddi, Finance Minister in the Madras government, by a KMP Kamma candidate in Udayagiri constituency. Reddi, who once remarked lightly in the Madras Assembly that his was "a Reddi government for Reddis,"65 told reporters that Kammas had "wreaked vengeance" on him.66 His supporters explained that a would-be Kamma candidate in Chingleput had been refused a Congress nomination by Congress leaders there. The Kammas in Udayagiri blamed it on backstage maneuvering by Reddi. This was one of the rare episodes in which Kamma- Reddi enmity had ever burst into the open.