Dr Führer's Wanderjahre: The Early Career of a Victorian Archaeologist

by Andrew Huxley

School of Oriental and African Studies

Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Third Series, Vol. 20, No. 4 (October, 2010), pp. 489-502

October, 2010

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

-- Dr Führer's Wanderjahre: The Early Career of a Victorian Archaeologist, by Andrew Huxley

-- Mr. [Bernard] Houghton and Dr. [Alois Anton] Führer: a scholarly vendetta and its consequences, by Andrew Huxley

-- Lumbini On Trial: The Untold Story. Lumbini Is An Astonishing Fraud Begun in 1896, by T. A. Phelps

-- The Piprahwa Deceptions: Set-ups and Showdown, by T.A. Phelps

-- Investigation of the Correctness of the Historical Dating, by Wieslaw Z. Krawcewicz, Gleb V. Nosovskij and Petr P. Zabreiko

-- Alois Anton Führer, by Wikipedia

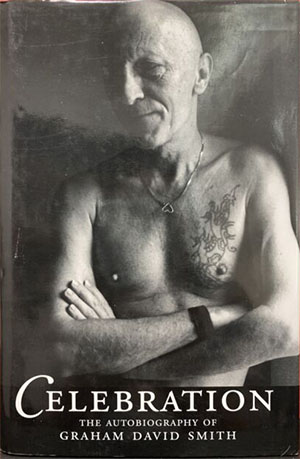

-- The Buddha and Dr. Fuhrer: An Archaeological Scandal, by Charles Allen

-- William Claxton Peppe: Persons of Indian Studies, by Prof. Dr. Klaus Karttunen

-- Monograph On Buddha Shakyamuni's Birth-Place: The Nepalese Tarai, by Alois Anton Fuhrer

-- Georg Bühler, by Wikipedia

-- Archaeological Survey of India, by Wikipedia

-- Vincent Arthur Smith, by Wikipedia

-- ART. XXIX.—The Conquests of Samudra Gupta, by VINCENT A. SMITH, M.B..A.S., Indian Civil Service

Abstract

The Rev. Dr A.A. Fuhrer lived to the age of seventy-seven. Herein is examined his first forty years. Trained as an Oriental Linguist, Fuhrer eventually found employment as a field archaeologist. Three years after his appointment, the Archaeological Survey of India entered the worst crisis of its existence. Fuhrer reacted in ways incompatible with scholarly integrity. It remains to be seen whether he committed further transgressions and or forgeries during his final thirty-seven years.

From 11 October 1894 to 6 January 1899 the Earl of Elgin served as Viceroy of India. Between these dates Rev. Dr A.A. Fuhrer, the Government Archaeologist of North-Western Provinces & Oudh (NWPO), achieved fame and notoriety through his research in the Butwal Terai (the stretch of Nepali lowland lying north of Patna and Varanasi). Upinder Singh describes Fuhrer's campaign in the Terai as "one of the most audacious frauds perpetrated in the history of nineteenth-century Indian archaeology".1 Janice Leoshko labels the official reports of his discoveries as 'false' and 'fraudulent'.2 To Charles Allen, Fuhrer's excavations in Nepal were 'badly botched' and his claims 'bogus'.3 Between 1894 and 1899 Fuhrer displayed the hubris, and suffered the nemesis, of a Sophoclean protagonist. Fuhrer was forty-one years old when his investigations into the Butwal Terai began. I examine Fuhrer's Bildung during his first forty years -- the Wanderjahre that took him across continents, vocations, and confessions.

1853-1885: Youth and Early Manhood

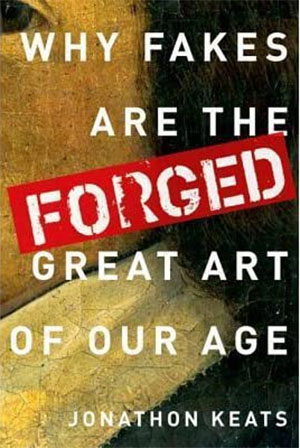

Alois Anton Fuhrer (1853-1930) studied Roman Catholic theology and Oriental studies at the University of Wurzburg. He received his Doctorate in 1876 and was ordained in 1877. His first posting, as Sanskrit teacher in the Jesuit College in Bombay, was probably secured through Julius Jolly, (a junior member of the Bombay School, who had taught Fuhrer at Wurzburg). Bombay in the 1870s was a leading spot for Indological studies,4 boasting Georg Buhler, Peter Peterson and James Burgess as residents. It was Buhler who was to play the leading role in Fuhrer's career.5 They first bonded when Buhler (who researched Hindu Law on the Government's behalf) recruited Fuhrer to edit a Dharmasastra for the Bombay Sanskrit Series.6 Buhler then helped Fuhrer to travel to London in order to copy out a Burmese-Pali law text held by the India Office, which Buhler knew of through an article by Reinhold Rost, the India Office Librarian.7 In London Rost guided Fuhrer through the palin-leaf itself and through the secondary literature, on Southeast Asian law. Fuhrer agreed to give two lectures to the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society on his research. These two lectures were printed in successive issues of the Society's Journal (JBBRAS).8 They are plagiarised to a startling degree.

Fuhrer's own words make up only a tenth of what he allowed to be printed under his name.9 Most of the first lecture transcribed a Preface to a Burmese Law work published four years earlier in British Burma by Colonel Horace Browne. Fuhrer's first three pages are also Browne's first three pages, save for differences in spelling. Then, where Browne describes his researches in Burma, Fuhrer replaces it with his own visit to London. The next two pages are lifted from Browne's second Preface, from Rost's article, and from Sangermano's 1833 monograph.10 For instance Rost's 'Von dem Dhammasat wurde nachmals von Indra dem King Byumandhi (Vyomandhi fur Vyomadhi?)' [Google translate: 'From the Dhammasat was afterward told by Indra the king Byumandhi (Vyomandhi for Vyomadhi?] became 'The work is said to have been revised in the time of King Byumandhi -- perhaps Vyomandhi instead of Vyomadhi (?)'. Fuhrer ends with two pages of original work that give a precis of the Burmese law text, chapter by chapter. His second lecture offered a generalised description of the rules and institutions of Burmese Law, as reflected in the Burmese law text. In fact he had taken these eight pages from an article on Siam.11 During the 1820s Major James Low of Penang had been the East India Company's expert on Siam. His studies of Siamese law were published twenty years later. Fuhrer had to alter Low's text to hide its provenance. Wherever Low wrote 'Siamese', Fuhrer substituted 'Burmese Buddhist', and wherever he used Thai words and phrases, Fuhrer cut them. However Fuhrer gave the game away by retaining a passage about Siamese sakdi-na: Burma never subscribed to this system of ranking princes and officials.12 He ended the second lecture with two pages of his own material, illustrating Burma's debt to the Sanskrit Manusmrti literature. I have analysed what Fuhrer added to this debate elsewhere.13 Fuhrer's first academic article was worse than plagiarised -- it was actively misleading. Siam is not Burma. Siamese law is not Burmese law.

Fuhrer's contemporaries in the field -- John Jardine, Em Forchhammer, Julius Jolly, and Rhys Davids -- spoke as if his work were a serious contribution to scholarship.14 Rost became aware of Fuhrer's borrowings by way of the India Office Library's subscription to JBBRAS. Fuhrer must have anticipated this outcome. Did he act heedless of the consequences, or did he calculate the risks in advance? If the latter, he must have been very confident of his relationship with Buhler. Usually in academia two patrons are better than one. Perhaps Fuhrer found himself under pressure to choose between Rost and Buhler (the two leading Anglophone Indologists of the day) as his sole patron. Shortly after Fuhrer's London trip, ill health forced Buhler to retire from his front-line duties in India to a Chair in Vienna. Fuhrer compounded his offence by claiming credit for a piece of research that Rost had himself carried out. Browne had raised the possibility of finding dhammathats in Sri Lankan book chests. However, "inquiries which have been made through the Ceylon branch of the Royal Asiatic Society ... have failed to elicit any information on the subject". Fuhrer altered this passage, to read "inquiries which I have made through the Buddhist high-priest, Mr Subhuti, in Colombo ... have failed to elicit any information on the subject".15 As it happens, the correspondence that Ven. Waskaduwe Pavara Neruttikacariya Mahavibhavi Subhuti Nayaka (1825-1905) conducted with foreign scholars has been preserved and published. There is no letter in Ven. Subhuti's files from either Fuhrer or Browne. There are, however, four letters from Rost enquiring about Sinhalese and Siamese equivalents of the Burmese dhammathats.16

Post-doctoral researchers gave lectures to bodies such as the Royal Asiatic Society in order to advertise their presence in the job-market. But Fuhrer, as a Catholic priest, could not enter the job market. At sometime in the early 1880s he lost his vocation, renounced his bishop's authority, and thereby lost his job at St Xavier's College, Bombay. He probably spent the year of 1884-85 in Germany and may have spent the two preceding years as well.17 Early in 1885 Sir Alfred Lyall, NWPO's Lieutenant-Governor, appointed Fuhrer as Curator of Lucknow Provincial Museum on a salary of Rs.250 per month. Fuhrer started work in March, and by September had transformed the hitherto 'gloomy' Museum into an 'attractive and most instructive' space. He opened out the ground floor to create a light well down to the lower gallery, and filled it with Buddhist sculptures. Lyall, the Chair of the Museum's Management Committee, greatly approved, and wrote to Calcutta asking whether a part-time job for Fuhrer could be found with the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). Fuhrer was "a person of considerable zeal and energy" as well as a "good Sanskrit scholar and epigraphist".18 Thus, late in 1885, Fuhrer's career as a Government Archaeologist began.

1885-1891: Beginner's Luck

The ASI, when Fuhrer joined it, was in a period of expansion. Having started in 1861 as the fiefdom of a single person, it now employed eleven staff. The expansion posed awkward questions about professional training and specialisation. In its early years the ASI's sole function had been to list northern India's antiquities. Major Alexander Cunningham spent his cold seasons conducting survey tours. Later his assistants carried them out for him. Between 1861 and 1885 Cunningham and his assistants filled twenty-three volumes with their reports. The 'survey tour' was a systematic campaign of description, transcription, and listing, supplemented by occasional excavations. Because the survey tourists rarely spent more than three nights in one place, they had little opportunity for significant discovery. Excavation, if it took place at all, was a hit-and-run affair. By the early 1880s specialist functions were being assigned to people with relevant training. Major H.H. Cole was appointed Curator of Ancient Monuments: mapping, drawing, photographing, and preserving India's monuments needed staff qualified as architects, engineers, or art teachers. J. F. Fleet (an ICS man who had learnt Sanskrit under Theodor Goldstucker) was appointed to head the Epigraphical Survey in 1882 [Epigraphical: An inscription, as on a statue or building]: a degree in oriental languages was preferred for those editing and publishing inscriptions.

-- The Tradition About the Corporeal Relics of Buddha, by J.F. Fleet, I.C.S. (Retd.), Ph.D., C.I.E.

-- Bhadrabahu, Chandragupta, and Sravana-Belgola, by J.F. Fleet, Bo.C.S., M.R.A.S., C.I.E.

-- Note on the Sarnath Inscription of Asvaghosha, by Arthur Venis, and Remarks on Professor Venis' Note, by J. F. Fleet

Despite its increased specialisation, in 1885 the ASI still bore Cunningham's stamp. He had developed a prose style -- aspiring to the sublime -- which influenced most of his staff; jungles were always 'dense', ruins 'vast', and sites 'deserted' and in his monograph on the Bhilsa Topes he had even sunk to quoting his own verses. At the head of his archaeological agenda Cunningham put three aims. Most important was to identify the sites within the Buddhist Holy Land mentioned in the Buddhist Canon and by the Chinese pilgrims Faxian and Xuanzang. Next in importance was to find more Ashokan epigraphy. James Prinsep's unravelling of the Brahmi alphabet used by Ashoka remains the greatest achievement of British archaeology in India, and Cunningham was keen to build on Prinsep's foundations. Finally, he aimed to discover examples of Hellenistic influence on early India, so as to argue that what was best in Indian art had come from Greece. The post-Cunningham ASI followed his agenda until at least the start of the twentieth century.

On joining the ASI Fuhrer was instructed to continue surveying NWPO. His first tour, undertaken early in 1886, took him northwest from Jaunpur, along the Gogra River and up to the Rapti River. On the way he collected forty-six inscriptions in Arabic, Persian and Sanskrit. One of the latter could, he said, help settle "the question of the time of the first appropriation of the ancient Buddhist and Hindu temples by the Musalmans". Inscription XLIV records "a Hindu king erecting a Vaisnava temple" in 1184 CE. Fuhrer discovered it not on the Hindu temple itself but as part of the rubble "re-used by Aurangzib in building his masjid".19 Since the demolition of Ayodya's Babri Mosque in 1992, Inscription XLIV has become newsworthy, not so much for its text as for its find-spot.20 Fuhrer visited the Buddha's birthplace (as identified by Cunningham) and the Buddha's favourite monastery at Savatthi (as identified by William Hoey in 1885). He rejected Cunningham's identification, but accepted Hoey's. Late in 1886 Fuhrer joined the Asiatic Society of Bengal, and submitted two short epigraphic papers to it.21 His second Survey Tour (1886-87) started in the Allahabad region, then moved northwest along the right bank of the Jumna River to Hamirpur. On the way he copied ten inscriptions in Arabic, twenty-four in Persian and two hundred and fifty in Sanskrit. The season's most successful event had been:

the entering of the almost inaccessible cave of Gopala, high up in the face of the hill of Prabhasa, by means of a wooden crib let down from the overhanging rocks of the hill.22

Within it he found an Indo-Scythian inscription from 47 BCE. With the third tour (1887-88) Fuhrer concentrated once more on the Buddhist Holy Land. He was, he said, "in search of ancient sites visited by the Chinese Buddhist pilgrims".23 Starting at Partabgarh, fifty miles north of Allahabad, he followed the Sal River northwest past Shahjahanpur to the promising sites of Mati and Ramnagar. In all he claimed seven positive identifications of places mentioned by Faxian and Xuanzang. Fuhrer's three Survey Tour Reports were not published, though Burgess from time to time printed highlights in the Academy.24 Fuhrer's first book on archaeology was a gazetteer of NWPO monumental antiquities. Following Cunningham's retirement, there was a belief that his printed legacy needed better organisation. Fuhrer was deputed to mould the contents of the twenty-three volumes, along with his own discoveries, into a single volume. At the same time Vincent Smith, the amateur NWPO antiquarian, compiled a full index to the volumes.25

-- The Early History of India, From 600 B.C. to the Muhammadan Conquest, Including the Invasion of Alexander the Great, by Vincent A. Smith, 1914

-- ART. XXIX.—The Conquests of Samudra Gupta, by Vincent A. Smith, M.B..A.S., Indian Civil Service

-- Coins of Ancient India: Catalogue of the Coins in the Indian Museum, Calcutta, Volume 1, by Vincent A. Smith, M.A. F.R.N.S., M.R.A.S., I.C.S. Retd.

Under Burgess' leadership, the ASI became much concerned with relations between its professional staff and the amateurs employed by the Indian Civil Service (ICS) and Indian Army. The amateurs, men like Hoey and Smith, far outranked the ASI staff in monthly salary and reputation. No professional had yet achieved anything as important as Hoey's discovery of Savatthi. Burgess sought to enhance the ASI's status by restricting the competition. Without the ASI's prior consent, Calcutta ruled, no 'person or agency' (that is, no amateur archaeologist, and no provincial government) could excavate anywhere in India. This was an ill-judged move. Some amateurs retaliated by refusing all cooperation with the ASI. J. Cockburn of the Opium Department [The East India Company ferried opium to China, and in due course fought the opium wars in order to seize an offshore base at Hong Kong and safeguard its profitable monopoly in narcotics.], having discovered the location of the Dragon Cave described by Xuanzang, "distinctly refused to let the cave's whereabouts be known to any officer of the ASI". When Fuhrer claimed the discovery as his own, Cockburn challenged him in an Indian newspaper, and the row spread to the London press. Cockburn had the Editor of Academy print a retraction of Fuhrer's claims.26 Burgess defended his assistant: Dr. Fuhrer had made the discovery quite independently "by descending the rock during the night to avoid the wild bees that infest it".27

The Chinese treatise known as the Hsi-yu-chi (or Si-yu- ki) is one of the classical Buddhist books of China, Korea, and Japan....

On the title-page of the Hsi-yu-chi it is represented as having been "translated" by Yuan-chuang and "redacted" or "compiled" by Pien-chi ([x]). But we are not to take the word for translate here in its literal sense, and all that it can be understood to convey is that the information given in the book was obtained by Yuan-chuang from foreign sources....

After sixteen year's absence Yuan-chuang returned to China and arrived at Ch'ang-an in the beginning of 645, the nineteenth year of the reign of T'ang T'ai Tsung....

Now he had arrived whole and well, and had become a many days' wonder. He had been where no other had ever been, he had seen and heard what no other had ever seen and heard. Alone he had crossed trackless wastes tenanted only by fierce ghost-demons. Bravely he had climbed fabled mountains high beyond conjecture, rugged and barren, ever chilled by icy wind and cold with eternal snow. He had been to the edge of the world and had seen where all things end. Now he was safely back to his native land, and with so great a quantity of precious treasures. There were 657 sacred books of Buddhism, some of which were full of mystical charms able to put to flight the invisible powers of mischief. All these books were in strange Indian language and writing, and were made of trimmed leaves of palm or of birch-bark strung together in layers. Then there were lovely images of the Buddha and his saints in gold, and silver, and crystal, and sandalwood. There were also many curious pictures and, above all, 150 relics, true relics of the Buddha. All these relics were borne on twenty horses and escorted into the city with great pomp and ceremony....

His faith was simple and almost unquestioning, and he had an aptitude for belief which has been called credulity. But his was not that credulity which lightly believes the impossible and accepts any statement merely because it is on record and suits the convictions or prejudices of the individual. Yuan-chuang always wanted to have his own personal testimony, the witness of his own senses or at least his personal experience. It is true his faith helped his unbelief, and it was too easy to convince him where a Buddhist miracle was concerned. A hole in the ground without any natural history, a stain on a rock without any explanation apparent, any object held sacred by the old religion of the fathers, and any marvel professing to be substantiated by the narrator, was generally sufficient to drive away his doubts and bring comforting belief. But partly because our pilgrim was thus too ready to believe, though partly also for other reasons, he did not make the best use of his opportunities. He was not a good observer, a careful investigator, or a satisfactory recorder, and consequently he left very much untold which he would have done well to tell....

After Yuan-chuang's death great and marvellous things were said of him. His body, it was believed, did not see corruption and he appeared to some of his disciples in visions of the night. In his lifetime he had been called a "Present Sakyamuni", and when he was gone his followers raised him to the rank of a founder of Schools or Sects in Buddhism. In one treatise we find the establishment of three of these schools ascribed to him, and in another work he is given as the founder in China of a fourth school. This last is said to have been originated in India at Nalanda by Silabhadra one of the great Buddhist monks there with whom Yuan-chuang studied....

-- On Yuan Chwang's Travels in India, 629-645 A.D., by Thomas Watters M.R.A.S., Edited After his Death by T.W. Rhys Davids, F.B.A. and S.W. Bushell, M.D., C.M.G., With Two Maps and an Itinerary by Vincent A. Smith

After 1891 the amateurs won back their ability to put on successful digs. Lawrence Waddell, an Indian Army Surgeon, excavated Ashoka's capital Pataliputta in 1892, and in 1896 Vincent Smith excavated Kasia, which he thought to be the site of the Buddha's final nirvana. But by then the professionals were able to boast their own successes.

In 1887 Fuhrer's superior in the NWPO office retired. Thenceforth Fuhrer worked without a professional supervisor. He felt that he had proved his competence as an archaeologist, and had earned the chance to spend a whole season at a single site. In print his lobbying was limited to describing the candidates for such a dig.28 He spoke of a return to Savatthi, "especially as the Maharanai of Balrampur is willing to grant a large subvention for this purpose". And he spoke, with particular enthusiasm, of Mati, where the surface of the ruins was "covered with large bricks" and walls "still rising up to 10 feet above the ground".29 From his Chair in Vienna Georg Buhler approved of Mati in particular and of three month excavations in general:

Should the excavations of the ancient sites be ever undertaken in real earnest, they would no doubt yield full information regarding the ancient history and political geography of the country, besides a mass of curiosities which might fill all the Museums of India and Europe and leave a great deal to spare.30

In his private discussions with Burgess, Buhler put the case for re-digging Mathura to look for early Jain material. Burgess agreed, and dug there himself in the 1887-88 season.31 Fuhrer apparently visited for a few days to handle the epigraphical finds -- the only hands-on lesson in archaeological methodology that Fuhrer was ever given. Burgess retired from India before the start of the 1888-89 season. Funding to continue at Mathura was still available, so Fuhrer stepped into the breach. Such was Fuhrer's success that he was allotted RS. 1,250 and four months to dig again at Mathura in 1889-90. These two campaigns made his reputation as the most successful of the professional excavators.

Within the Kankali mound at Mathura Fuhrer found hundreds of Jain sculptures and epigraphs. None praised these discoveries more than Buhler, who had "for many years guided Fuhrer in his explorations, interpreted his results, and published the more important results".32 Kankali, Buhler announced, "has by no means yielded up all its treasures". "Next season Fuhrer should be sent back to examine 'the oldest Jaina temples"'. Buhler's lobbying can read disconcertingly like prediction. Next year's finds would "without a doubt completely free their creed from the suspicion of being a modern offshoot of Buddhism".33 In 1890, advocating a third season devoted to Chaubara mound he said it "undoubtedly hides the ruins of an ancient Vaishnava temple". 34 There is, however, little hyperbole in Buhler's praise of Fuhrer. The digs at Mathura really did yield enough sculpture to stock a new Museum at Mathura, and to overfill the existing Lucknow Museum. They really did produce enough inscriptions for Buhler to write twenty articles in Vienna Oriental Journal, Academy, and Epigraphia Indica. Fuhrer's finds really were "important additions to our knowledge of Indian history and art". Money really had been "spent to good purpose and in the interest of Indian history". 35

Buhler attributed Fuhrer's success to his "energy and perseverance".36 Luck may also have been a factor. Fuhrer lacked the perseverance to write up his Mathura campaigns as a scholarly monograph, and lacked the energy to make a proper catalogue of the artefacts he dug up. His entries in the published acquisition lists tantalise as much as they reveal. It is little help to be told, without further detail, of "74 statues of Jinas, inscribed between BC 200 to AD 150" or of "10 pieces of old pottery filled with the ashes of some Jaina monks".37 Nor, apparently, was Fuhrer energetic enough to write his own Progress Reports, which borrow extensively from Buhler's previous publications. Four-fifths of the 1890-91 Report consists of words previously published by Buhler. Two pages of Buhler's discussion of Jain nuns in the Vienna Oriental Journal became one page of Fuhrer's Report. Two pages of Buhler's account in Academy was edited down into a page of his own. He ended with a borrowed paragraph from Buhler's most recent article in Vienna Oriental Journal.38 This is not, however, a true case of plagiarism. Fuhrer's letters to Buhler from Mathura (which unfortunately no longer exist) must have contained phrases and sentences that Buhler incorporated into his own text. They must have understood themselves as co-authors, free to publish the shared material under either's name. Fuhrer and Buhler made an unwritten, and probably tacit, contract of partnership, the terms of which are implicit in their interaction. Scholars today should be able to reconstruct these terms from the public record. However they disagree widely. One body of opinion regards Fuhrer and Buhler as compliant with best scholarly practice. The middling view construes them as business partners, with Fuhrer handling acquisitions in India, and Buhler in charge of European marketing. At the other extreme, they are seen as partners in crime.

James Burgess, Director-General of the ASI, expressed his satisfaction with Fuhrer's "trained and varied scholarship" which "sufficiently guarantee the accuracy" of his work on Jaunpur.39 In any well-run institution, such praise would have brought Fuhrer commendation and promotion. Instead he was threatened with the sack. Viceroy Dufferin's expansion of the ASI had attracted powerful opposition, which clamoured incessantly for cuts to the ASI budget.40 None in Calcutta was more clamorous than Edward Buck.41 Buck was committed to implementing Viceroy Lord Ripon's Liberal policies. To bolster the Arts and Manufactures of India he planned to build Museums in each of "the great Indian centres". These would be "sample rooms where the best examples of Indian craftsmanship might be seen". To this end he sought Revenue and Agriculture Department funding for a new Journal of Indian Art and Industry. In 1884 these expensive plans were cancelled by the incoming Conservative Secretariat under Lord Dufferin, and the funds diverted from Arts and Crafts to Archaeology. Buck bounced back in 1888 under Viceroy Lord Lansdowne. Buck drove Burgess to resign, then froze any appointment of a successor, then transferred the ASI wage bill from the central to the provincial budget. A correspondent in the Pioneer summarised Buck's arguments. In the good old days amateur archaeologists investigated India "as a labour of love in their leisure hours". But during the 1880s Government came to:

entertain at very high salaries learned antiquarians and a large and most expensive staff of officers to pervade the past and patrol the night of time in a vague and general way -- and with vague and general results.42

The 'Buck crisis' lasted for more than a decade, and moved through three phases.43

The first phase (from 1888 to 1891) hit all the ASI staff, but Fuhrer, two years married and recently become a father, was hit particularly hard. The threat of dismissal felt like poor recompense for his successes at Mathura. If honest toil went unrewarded, why not pursue international acclaim by other means? If the Government maltreated him, why not play it for a fool? A motive for misbehaviour was emerging, and so too were opportunities. Starting in 1891 Fuhrer's Progress Reports were distributed to select learned institutions in Europe and India without any external vetting.44 The shift to Provincial funding in 1891 meant that, though theoretically Fuhrer answered to the Lieutenant-Governor of NWPO and to the Revenue & Agriculture Secretary in Calcutta, in practice he worked without any supervision.