Part 2 of 2

In British Imperial debatesSmith's chapter on colonies, in turn, would help shape British imperial debates from the mid-19th century onward. The Wealth of Nations would become an ambiguous text regarding the imperial question. In his chapter on colonies, Smith pondered how to solve the crisis developing across the Atlantic among the empire's 13 American colonies. He offered two different proposals for easing tensions. The first proposal called for giving the colonies their independence, and by thus parting on a friendly basis, Britain would be able to develop and maintain a free-trade relationship with them, and possibly even an informal military alliance. Smith's second proposal called for a theoretical imperial federation that would bring the colonies and the metropole closer together through an imperial parliamentary system and imperial free trade.[113]

Smith's most prominent disciple in 19th-century Britain, peace advocate Richard Cobden, preferred the first proposal. Cobden would lead the Anti-Corn Law League in overturning the Corn Laws in 1846, shifting Britain to a policy of free trade and empire "on the cheap" for decades to come. This hands-off approach toward the British Empire would become known as Cobdenism or the Manchester School.[114] By the turn of the century, however, advocates of Smith's second proposal such as Joseph Shield Nicholson would become ever more vocal in opposing Cobdenism, calling instead for imperial federation.[115] As Marc-William Palen notes: "On the one hand, Adam Smith’s late nineteenth and early twentieth-century Cobdenite adherents used his theories to argue for gradual imperial devolution and empire ‘on the cheap’. On the other, various proponents of imperial federation throughout the British World sought to use Smith's theories to overturn the predominant Cobdenite hands-off imperial approach and instead, with a firm grip, bring the empire closer than ever before."[116] Smith's ideas thus played an important part in subsequent debates over the British Empire.

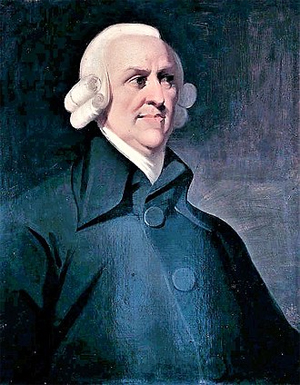

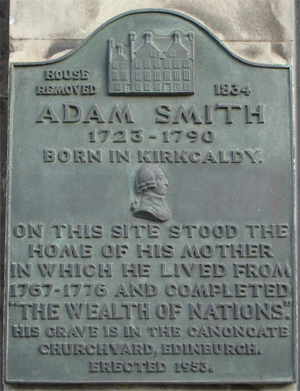

Portraits, monuments, and banknotes A statue of Smith in Edinburgh's High Street, erected through private donations organised by the Adam Smith Institute

A statue of Smith in Edinburgh's High Street, erected through private donations organised by the Adam Smith InstituteSmith has been commemorated in the UK on banknotes printed by two different banks; his portrait has appeared since 1981 on the £50 notes issued by the Clydesdale Bank in Scotland,[117][118] and in March 2007 Smith's image also appeared on the new series of £20 notes issued by the Bank of England, making him the first Scotsman to feature on an English banknote.[119]

Statue of Smith built in 1867–1870 at the old headquarters of the University of London, 6 Burlington Gardens

Statue of Smith built in 1867–1870 at the old headquarters of the University of London, 6 Burlington GardensA large-scale memorial of Smith by Alexander Stoddart was unveiled on 4 July 2008 in Edinburgh. It is a 10-foot (3.0 m)-tall bronze sculpture and it stands above the Royal Mile outside St Giles' Cathedral in Parliament Square, near the Mercat cross.[120] 20th-century sculptor Jim Sanborn (best known for the Kryptos sculpture at the United States Central Intelligence Agency) has created multiple pieces which feature Smith's work. At Central Connecticut State University is Circulating Capital, a tall cylinder which features an extract from The Wealth of Nations on the lower half, and on the upper half, some of the same text, but represented in binary code.[121] At the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, outside the Belk College of Business Administration, is Adam Smith's Spinning Top.[122][123] Another Smith sculpture is at Cleveland State University.[124] He also appears as the narrator in the 2013 play The Low Road, centred on a proponent on laissez-faire economics in the late 18th century, but dealing obliquely with the financial crisis of 2007–2008 and the recession which followed; in the premiere production, he was portrayed by Bill Paterson.

A bust of Smith is in the Hall of Heroes of the National Wallace Monument in Stirling.

ResidenceAdam Smith resided at Panmure House from 1778 to 1790. This residence has now been purchased by the Edinburgh Business School at Heriot Watt University and fundraising has begun to restore it.[125][126] Part of the Northern end of the original building appears to have been demolished in the 19th century to make way for an iron foundry.

As a symbol of free-market economics Adam Smith's Spinning Top, sculpture by Jim Sanborn at Cleveland State University

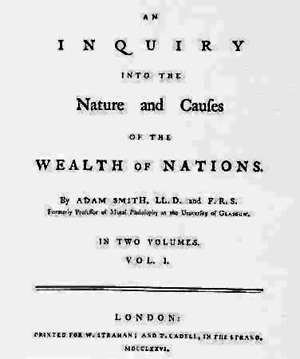

Adam Smith's Spinning Top, sculpture by Jim Sanborn at Cleveland State UniversitySmith has been celebrated by advocates of free-market policies as the founder of free-market economics, a view reflected in the naming of bodies such as the Adam Smith Institute in London, multiple entities known as the "Adam Smith Society", including an historical Italian organization,[127] and the U.S.-based Adam Smith Society,[128][129] and the Australian Adam Smith Club,[130] and in terms such as the Adam Smith necktie.[131]

Alan Greenspan argues that, while Smith did not coin the term laissez-faire, "it was left to Adam Smith to identify the more-general set of principles that brought conceptual clarity to the seeming chaos of market transactions". Greenspan continues that The Wealth of Nations was "one of the great achievements in human intellectual history".[132] P.J. O'Rourke describes Smith as the "founder of free market economics".[133]

Other writers have argued that Smith's support for laissez-faire (which in French means leave alone) has been overstated. Herbert Stein wrote that the people who "wear an Adam Smith necktie" do it to "make a statement of their devotion to the idea of free markets and limited government", and that this misrepresents Smith's ideas. Stein writes that Smith "was not pure or doctrinaire about this idea. He viewed government intervention in the market with great skepticism...yet he was prepared to accept or propose qualifications to that policy in the specific cases where he judged that their net effect would be beneficial and would not undermine the basically free character of the system. He did not wear the Adam Smith necktie." In Stein's reading, The Wealth of Nations could justify the Food and Drug Administration, the Consumer Product Safety Commission, mandatory employer health benefits, environmentalism, and "discriminatory taxation to deter improper or luxurious behavior".[134]

Similarly, Vivienne Brown stated in The Economic Journal that in the 20th-century United States, Reaganomics supporters, the Wall Street Journal, and other similar sources have spread among the general public a partial and misleading vision of Smith, portraying him as an "extreme dogmatic defender of laissez-faire capitalism and supply-side economics".[135] In fact, The Wealth of Nations includes the following statement on the payment of taxes:

The subjects of every state ought to contribute towards the support of the government, as nearly as possible, in proportion to their respective abilities; that is, in proportion to the revenue which they respectively enjoy under the protection of the state.[136]

Some commentators have argued that Smith's works show support for a progressive, not flat, income tax and that he specifically named taxes that he thought should be required by the state, among them luxury-goods taxes and tax on rent.[137] Yet Smith argued for the "impossibility of taxing the people, in proportion to their economic revenue, by any capitation" (The Wealth of Nations, V.ii.k.1). Smith argued that taxes should principally go toward protecting "justice" and "certain publick institutions" that were necessary for the benefit of all of society, but that could not be provided by private enterprise (The Wealth of Nations, IV.ix.51).

Additionally, Smith outlined the proper expenses of the government in The Wealth of Nations, Book V, Ch. I. Included in his requirements of a government is to enforce contracts and provide justice system, grant patents and copy rights, provide public goods such as infrastructure, provide national defence, and regulate banking. The role of the government was to provide goods "of such a nature that the profit could never repay the expense to any individual" such as roads, bridges, canals, and harbours. He also encouraged invention and new ideas through his patent enforcement and support of infant industry monopolies. He supported partial public subsidies for elementary education, and he believed that competition among religious institutions would provide general benefit to the society. In such cases, however, Smith argued for local rather than centralised control: "Even those publick works which are of such a nature that they cannot afford any revenue for maintaining themselves ... are always better maintained by a local or provincial revenue, under the management of a local and provincial administration, than by the general revenue of the state" (Wealth of Nations, V.i.d.18). Finally, he outlined how the government should support the dignity of the monarch or chief magistrate, such that they are equal or above the public in fashion. He even states that monarchs should be provided for in a greater fashion than magistrates of a republic because "we naturally expect more splendor in the court of a king than in the mansion-house of a doge".[138] In addition, he allowed that in some specific circumstances, retaliatory tariffs may be beneficial:

The recovery of a great foreign market will generally more than compensate the transitory inconvenience of paying dearer during a short time for some sorts of goods.[139]

However, he added that in general, a retaliatory tariff "seems a bad method of compensating the injury done to certain classes of our people, to do another injury ourselves, not only to those classes, but to almost all the other classes of them" (The Wealth of Nations, IV.ii.39).

Economic historians such as Jacob Viner regard Smith as a strong advocate of free markets and limited government (what Smith called "natural liberty"), but not as a dogmatic supporter of laissez-faire.[140]

Economist Daniel Klein believes using the term "free-market economics" or "free-market economist" to identify the ideas of Smith is too general and slightly misleading. Klein offers six characteristics central to the identity of Smith's economic thought and argues that a new name is needed to give a more accurate depiction of the "Smithian" identity.[141][142] Economist David Ricardo set straight some of the misunderstandings about Smith's thoughts on free market. Most people still fall victim to the thinking that Smith was a free-market economist without exception, though he was not. Ricardo pointed out that Smith was in support of helping infant industries. Smith believed that the government should subsidise newly formed industry, but he did fear that when the infant industry grew into adulthood, it would be unwilling to surrender the government help.[143] Smith also supported tariffs on imported goods to counteract an internal tax on the same good. Smith also fell to pressure in supporting some tariffs in support for national defence.[143]

Some have also claimed, Emma Rothschild among them, that Smith would have supported a minimum wage,[144] although no direct textual evidence supports the claim. Indeed, Smith wrote:

The price of labour, it must be observed, cannot be ascertained very accurately anywhere, different prices being often paid at the same place and for the same sort of labour, not only according to the different abilities of the workmen, but according to the easiness or hardness of the masters. Where wages are not regulated by law, all that we can pretend to determine is what are the most usual; and experience seems to show that law can never regulate them properly, though it has often pretended to do so. (The Wealth of Nations, Book 1, Chapter 8)

However, Smith also noted, to the contrary, the existence of an imbalanced, inequality of bargaining power:[145]

A landlord, a farmer, a master manufacturer, a merchant, though they did not employ a single workman, could generally live a year or two upon the stocks which they have already acquired. Many workmen could not subsist a week, few could subsist a month, and scarce any a year without employment. In the long run, the workman may be as necessary to his master as his master is to him, but the necessity is not so immediate.

CriticismAlfred Marshall criticised Smith's definition of the economy on several points. He argued that man should be equally important as money, services are as important as goods, and that there must be an emphasis on human welfare, instead of just wealth. The "invisible hand" only works well when both production and consumption operates in free markets, with small ("atomistic") producers and consumers allowing supply and demand to fluctuate and equilibrate. In conditions of monopoly and oligopoly, the "invisible hand" fails.

Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph E. Stiglitz says, on the topic of one of Smith's better-known ideas: "the reason that the invisible hand often seems invisible is that it is often not there."[146]

See also• Organizational capital

• List of abolitionist forerunners

• List of Fellows of the Royal Society of Arts

• People on Scottish banknotes

References

Informational notes1. In Life of Adam Smith, Rae writes: "In his fourth year, while on a visit to his grandfather's house at Strathendry on the banks of the Leven, [Smith] was stolen by a passing band of gypsies, and for a time could not be found. But presently a gentleman arrived who had met a Romani woman a few miles down the road carrying a child that was crying piteously. Scouts were immediately dispatched in the direction indicated, and they came upon the woman in Leslie wood. As soon as she saw them she threw her burden down and escaped, and the child was brought back to his mother. [Smith] would have made, I fear, a poor gypsy."[14]

2. During the reign of Louis XIV, the population shrunk by 4 million and agricultural productivity was reduced by one-third while the taxes had increased. Cusminsky, Rosa, de Cendrero, 1967, Los Fisiócratas, Buenos Aires: Centro Editor de América Latina, p. 6

3. 1701–1714 War of the Spanish Succession, 1688–1697 War of the Grand Alliance, 1672–1678 Franco-Dutch War, 1667–1668 War of Devolution, 1618–1648 Thirty Years' War

4. The 6 editions of The Theory of Moral Sentiments were published in 1759, 1761, 1767, 1774, 1781, and 1790, respectively.[73]

Citations1. "Adam Smith (1723–1790)". BBC. Adam Smith's exact date of birth is unknown, but he was baptised on 5 June 1723.

2. Nevin, Seamus (2013). "Richard Cantillon: The Father of Economics". History Ireland. 21 (2): 20–23. JSTOR 41827152.

3. Billington, James H. (1999). Fire in the Minds of Men: Origins of the Revolutionary Faith. Transaction Publishers. p. 302.

4. Stedman Jones, Gareth (2006). "Saint-Simon and the Liberal origins of the Socialist critique of Political Economy". In Aprile, Sylvie; Bensimon, Fabrice (eds.). La France et l'Angleterre au XIXe siècle. Échanges, représentations, comparaisons. Créaphis. pp. 21–47.

5. "Great Thinkers of the Scottish Enlightenment".

6. Sharma, Rakesh. "Adam Smith: The Father of Economics". Investopedia. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

7. "Adam Smith: Father of Capitalism".

http://www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

8. "Absolute Advantage – Ability to Produce More than Anyone Else". Corporate Finance Institute. Retrieved 20 February2019.

9. "Adam Smith: Biography on Undiscovered Scotland".

http://www.undiscoveredscotland.co.uk. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

10. John, McMurray (19 March 2017). "Capitalism's 'Founding Father' Often Quoted, Frequently Misconstrued". Investor.com. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

11. Rae 1895, p. 1

12. Bussing-Burks 2003, pp. 38–39

13. Buchan 2006, p. 12

14. Rae 1895, p. 5

15. Bussing-Burks 2003, p. 39

16. Buchan 2006, p. 22

17. Bussing-Burks 2003, p. 41

18. Rae 1895, p. 24

19. Buchholz 1999, p. 12

20. Introductory Economics. New Age Publishers. December 2006. p. 4. ISBN 81-224-1830-9.

21. Rae 1895, p. 22

22. Rae 1895, pp. 24–25

23. Bussing-Burks 2003, p. 42

24. Buchan 2006, p. 29

25. Scott, W. R. "The Never to Be Forgotten Hutcheson: Excerpts from W. R. Scott," Econ Journal Watch 8(1): 96–109, January 2011.[1] Archived 28 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

26. "Adam Smith". Biography. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

27. Rae 1895, p. 30

28. Smith, A. ([1762] 1985). Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres [1762]. vol. IV of the Glasgow Edition of the Works and Correspondence of Adam Smith (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1984). Retrieved 16 February 2012

29. Bussing-Burks 2003, p. 43

30. Winch, Donald (September 2004). "Smith, Adam (bap. 1723, d. 1790)". Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

31. Rae 1895, p. 42

32. Buchholz 1999, p. 15

33. Buchan 2006, p. 67

34. Buchholz 1999, p. 13

35. "MyGlasgow – Archive Services – Exhibitions – Adam Smith in Glasgow – Photo Gallery – Honorary degree". University of Glasgow. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

36. Buchholz 1999, p. 16

37. Buchholz 1999, pp. 16–17

38. Buchholz 1999, p. 17

39. Smith, A., 1976, The Wealth of Nations edited by R. H. Campbell and A. S. Skinner, The Glasgow edition of the Works and Correspondence of Adam Smith, vol. 2b, p. 678.

40. Buchholz 1999, p. 18

41. Buchan 2006, p. 90

42. Dr James Currie to Thomas Creevey, 24 February 1793, Lpool RO, Currie MS 920 CUR

43. Buchan 2006, p. 89

44. Buchholz 1999, p. 19

45. Durant, Will; Durant, Ariel (1 July 1967). The Story of Civilization: Rousseau and Revolution. MJF Books. ISBN 1567310214.

46. Buchan 2006, p. 128

47. Buchan 2006, p. 133

48. Buchan 2006, p. 137

49. Buchan 2006, p. 145

50. Bussing-Burks 2003, p. 53

51. Buchan 2006, p. 25

52. Buchan 2006, p. 88

53. Bonar, James, ed. (1894). "Adam Smith's Will". A Catalogue of the Library of Adam Smith. London: Macmillan. pp. XIV. OCLC 2320634. Retrieved 13 May 2018 – via Internet Archive.

54. Bonar 1895, pp. xx–xxiv

55. Buchan 2006, p. 11

56. Buchan 2006, p. 134

57. Rae 1895, p. 262

58. Skousen 2001, p. 32

59. Buchholz 1999, p. 14

60. Boswell's 'Life of Samuel Johnson, 1780.

61. Ross 2010, p. 330

62. Stewart, Dugald (1853). The Works of Adam Smith: With An Account of His Life and Writings. London: Henry G. Bohn. lxix. OCLC 3226570.

63. Rae 1895, pp. 376–77

64. Bonar 1895, p. xxi

65. Ross 1995, p. 15

66. "Times obituary of Adam Smith". The Times:

http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Times ... Adam_Smith. 24 July 1790.

67. Coase 1976, pp. 529–46

68. Coase 1976, p. 538

69. Hill, L. (2001). "The hidden theology of Adam Smith". The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought. 8: 1–29. doi:10.1080/713765225.

70. "Hume on Religion". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 26 May 2008.

71. Eric Schliesser (2003). "The Obituary of a Vain Philosopher: Adam Smith's Reflections on Hume's Life" (PDF). Hume Studies. 29 (2): 327–62. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

72. "Andrew Millar Project, University of Edinburgh". millar-project.ed.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

73. Adam Smith, Glasgow Edition of the Works and Correspondence Vol. 1 The Theory of Moral Sentiments [1759].

74. Rae 1895

75. Falkner, Robert (1997). "Biography of Smith". Liberal Democrat History Group. Archived from the original on 11 June 2008. Retrieved 14 May 2008.

76. Smith 2002, p. xv

77. Viner 1991, p. 250

78. Wight, Jonathan B. Saving Adam Smith. Upper Saddle River: Prentic-Hall, Inc., 2002.

79. Robbins, Lionel. A History of Economic Thought. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998.

80. Brue, Stanley L., and Randy R. Grant. The Evolution of Economic Thought. Mason: Thomson Higher Education, 2007.

81. Otteson, James R. 2002, Adam Smith's Marketplace of Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

82. Ekelund, R. & Hebert, R. 2007, A History of Economic Theory and Method 5th Edition. Waveland Press, United States, p. 105.

83. Smith, A., 1976, The Wealth of Nations edited by R. H. Campbell and A. S. Skinner, The Glasgow edition of the Works and Correspondence of Adam Smith, vol. 2a, p. 456.

84. Smith, A., 1980, The Glasgow edition of the Works and Correspondence of Adam Smith, vol. 3, p. 49, edited by W. P. D. Wightman and J. C. Bryce, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

85. Smith, A., 1976, The Glasgow edition of the Works and Correspondence of Adam Smith, vol. 1, pp. 184–85, edited by D. D. Raphael and A. L. Macfie, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

86. Smith, A., 1976, The Glasgow edition of the Works and Correspondence of Adam Smith, vol. 2a, p. 456, edited by R. H. Cambell and A. S. Skinner, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

87. Smith, A., 1976, The Glasgow edition, vol. 2a, pp. 26–27.

88. Mandeville, B., 1724, The Fable of the Bees, London: Tonson.

89. Smith, A., 1976, The Glasgow edition, vol. 2a, pp. 145, 158.

90. Smith, A., 1976, The Glasgow edition, vol. 2a, p. 79.

91. Gopnik, Adam. "Market Man". The New Yorker (18 October 2010): 82. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

92. Samuelson, P. A./Nordhaus, William D., 1989, Economics, 13th edition, N.Y. et al.: McGraw-Hill, p. 825.

93. Samuelson, P. A./Nordhaus, William D., 1989, idem, p. 825.

94. Buchan 2006, p. 80

95. Stewart, D., 1799, Essays on Philosophical Subjects, to which is prefixed An Account of the Life and Writings of the Author by Dugald Steward, F.R.S.E., Basil; from the Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Read by M. Steward, 21 January, and 18 March 1793; in: The Glasgow edition of the Works and Correspondence of Adam Smith, 1982, vol. 3, pp. 304 ff.

96. Smith, A., 1976, vol. 2a, p. 10, idem

97. Smith, A., 1976, vol. 1, p. 10, para. 4

98. The Glasgow edition of the Works and Correspondence of Adam Smith, 1982, 6 volumes

99. "Adam Smith – Jonathan Swift". University of Winchester. Archived from the original on 28 November 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

100. 100 Best Scottish Books, Adam Smith Retrieved 31 January 2012

101. L.Seabrooke (2006). "Global Standards of Market Civilization". p. 192. Taylor & Francis 2006

102. Stigler, George J. (1976). "The Successes and Failures of Professor Smith," Journal of Political Economy, 84(6), pp. 1199–213, 1202. Also published as Selected Papers, No. 50 (PDF)[permanent dead link], Graduate School of Business, University of Chicago.

103. Samuelson, Paul A. (1977). "A Modern Theorist's Vindication of Adam Smith," American Economic Review, 67(1), p. 42.Reprinted in J.C. Wood, ed., Adam Smith: Critical Assessments, pp. 498–509. Preview.

104. Schumpeter History of Economic Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 185.

105. Roemer, J.E. (1987). "Marxian Value Analysis". The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 3, 383.

106. Mandel, Ernest (1987). "Marx, Karl Heinrich", The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics v. 3, pp. 372, 376.

107. Marshall, Alfred; Marshall, Mary Paley (1879). The Economics of Industry. p. 2.

108. Jevons, W. Stanley (1879). The Theory of Political Economy (2nd ed.). p. xiv.

109. Clark, B. (1998). Political-economy: A comparative approach, 2nd ed., Westport, CT: Praeger. p. 32.

110. Campos, Antonietta (1987). "Marginalist Economics", The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 3, p. 320

111. Smith 1977, §Book I, Chapter 2

112. "The Vanity of the Philosopher: From Equality to Hierarchy" in Postclassical Economics [2] Archived 4 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

113. E.A. Benians, ‘Adam Smith’s project of an empire’, Cambridge Historical Journal 1 (1925): 249–83

114. Anthony Howe, Free trade and liberal England, 1846–1946 (Oxford, 1997)

115. J. Shield Nicholson, A project of empire: a critical study of the economics of imperialism, with special reference to the ideas of Adam Smith (London, 1909)

116. Marc-William Palen, “Adam Smith as Advocate of Empire, c. 1870–1932,” Historical Journal 57: 1 (March 2014): 179–98.

117. "Clydesdale 50 Pounds, 1981". Ron Wise's Banknoteworld. Archived from the original on 30 October 2008. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

118. "Current Banknotes : Clydesdale Bank". The Committee of Scottish Clearing Bankers. Archived from the original on 3 October 2008. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

119. "Smith replaces Elgar on £20 note". BBC. 29 October 2006. Archived from the original on 24 March 2007. Retrieved 14 May 2008.

120. Blackley, Michael (26 September 2007). "Adam Smith sculpture to tower over Royal Mile". Edinburgh Evening News.

121. Fillo, Maryellen (13 March 2001). "CCSU welcomes a new kid on the block". The Hartford Courant.

122. Kelley, Pam (20 May 1997). "Piece at UNCC is a puzzle for Charlotte, artist says". Charlotte Observer.

123. Shaw-Eagle, Joanna (1 June 1997). "Artist sheds new light on sculpture". The Washington Times.

124. "Adam Smith's Spinning Top". Ohio Outdoor Sculpture Inventory. Archived from the original on 5 February 2005. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

125. "The restoration of Panmure House". Archived from the original on 22 January 2012.

126. "Adam Smith's Home Gets Business School Revival". Bloomberg.

127. "The Adam Smith Society". The Adam Smith Society. Archived from the original on 21 July 2007. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

128. Choi, Amy (4 March 2014). "Defying Skeptics, Some Business Schools Double Down on Capitalism". Bloomberg Business News. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

129. "Who We Are: The Adam Smith Society". April 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

130. "The Australian Adam Smith Club". Adam Smith Club. Archived from the original on 9 May 2010. Retrieved 12 October2008.

131. Levy, David (June 1992). "Interview with Milton Friedman". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved 1 September2008.

132. "FRB: Speech, Greenspan – Adam Smith – 6 February 2005". Archived from the original on 12 May 2008. Retrieved 31 May 2008.

133. "Adam Smith: Web Junkie". Forbes. 5 July 2007. Archived from the original on 20 May 2008. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

134. Stein, Herbert (6 April 1994). "Board of Contributors: Remembering Adam Smith". The Wall Street Journal Asia: A14.

135. Brown, Vivienne; Pack, Spencer J.; Werhane, Patricia H. (January 1993). "Untitled review of 'Capitalism as a Moral System: Adam Smith's Critique of the Free Market Economy' and 'Adam Smith and his Legacy for Modern Capitalism'". The Economic Journal. 103 (416): 230–32. doi:10.2307/2234351. JSTOR 2234351.

136. Smith 1977, bk. V, ch. 2

137. "Market Man". The New Yorker. 18 October 2010.

138. Smith 1977, bk. V

139. Smith, A., 1976, The Glasgow edition, vol. 2a, p. 468.

140. Viner, Jacob (April 1927). "Adam Smith and Laissez-faire". The Journal of Political Economy. 35 (2): 198–232. doi:10.1086/253837. JSTOR 1823421.

141. Klein, Daniel B. (2008). "Toward a Public and Professional Identity for Our Economics". Econ Journal Watch. 5 (3): 358–72. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

142. Klein, Daniel B. (2009). "Desperately Seeking Smithians: Responses to the Questionnaire about Building an Identity". Econ Journal Watch. 6 (1): 113–80. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

143. Buchholz, Todd (December 1990). pp. 38–39.

144. Martin, Christopher. "Adam Smith and Liberal Economics: Reading the Minimum Wage Debate of 1795–96," Econ Journal Watch 8(2): 110–25, May 2011 [3] Archived 28 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

145. A Smith, Wealth of Nations (1776) Book I, ch 8

146. The Roaring Nineties, 2006

Bibliography• Benians, E. A. (1925). "II. Adam Smith's Project of an Empire". Cambridge Historical Journal. 1 (3): 249–283. doi:10.1017/S1474691300001062.

• Bonar, James, ed. (1894). A Catalogue of the Library of Adam Smith. London: Macmillan. OCLC 2320634 – via Internet Archive.

• Buchan, James (2006). The Authentic Adam Smith: His Life and Ideas. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-06121-3.

• Buchholz, Todd (1999). New Ideas from Dead Economists: An Introduction to Modern Economic Thought. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-028313-7.

• Bussing-Burks, Marie (2003). Influential Economists. Minneapolis: The Oliver Press. ISBN 1-881508-72-2.

• Campbell, R.H.; Skinner, Andrew S. (1985). Adam Smith. Routledge. ISBN 0-7099-3473-4.

• Coase, R.H. (October 1976). "Adam Smith's View of Man". The Journal of Law and Economics. 19 (3): 529–46. doi:10.1086/466886.

• Helbroner, Robert L. The Essential Adam Smith. ISBN 0-393-95530-3

• Nicholson, J. Shield (1909). A project of empire;a critical study of the economics of imperialism, with special reference to the ideas of Adam Smith. hdl:2027/uc2.ark:/13960/t4th8nc9p.

• Otteson, James R. (2002). Adam Smith's Marketplace of Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-01656-8

• Palen, Marc-William (2014). "ADAM SMITH AS ADVOCATE OF EMPIRE, c. 1870–1932". The Historical Journal. 57: 179–198. doi:10.1017/S0018246X13000101.

• Rae, John (1895). Life of Adam Smith. London & New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0-7222-2658-6. Retrieved 14 May 2018 – via Internet Archive.

• Ross, Ian Simpson (1995). The Life of Adam Smith. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-828821-2.

• Ross, Ian Simpson (2010). The Life of Adam Smith (2 ed.). Oxford University Press.

• Skousen, Mark (2001). The Making of Modern Economics: The Lives and Ideas of Great Thinkers. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0-7656-0480-9.

• Smith, Adam (1977) [1776]. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-76374-9.

• Smith, Adam (1982) [1759]. D.D. Raphael and A.L. Macfie (ed.). The Theory of Moral Sentiments. Liberty Fund. ISBN 0-86597-012-2.

• Smith, Adam (2002) [1759]. Knud Haakonssen (ed.). The Theory of Moral Sentiments. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-59847-8.

• Smith, Vernon L. (July 1998). "The Two Faces of Adam Smith". Southern Economic Journal. 65 (1): 2–19. doi:10.2307/1061349. JSTOR 1061349.

• Tribe, Keith; Mizuta, Hiroshi (2002). A Critical Bibliography of Adam Smith. Pickering & Chatto. ISBN 978-1-85196-741-4.

• Viner, Jacob (1991). Douglas A. Irwin (ed.). Essays on the Intellectual History of Economics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-04266-7.

Further reading• Butler, Eamonn (2007). Adam Smith – A Primer. Institute of Economic Affairs. ISBN 978-0-255-36608-3.

• Cook, Simon J. (2012). "Culture & Political Economy: Adam Smith & Alfred Marshall". Tabur.

• Copley, Stephen (1995). Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations: New Interdisciplinary Essays. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-3943-6.

• Glahe, F. (1977). Adam Smith and the Wealth of Nations: 1776–1976. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 0-87081-082-0.

• Haakonssen, Knud (2006). The Cambridge Companion to Adam Smith. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-77924-3.

• Hardwick, D. and Marsh, L. (2014). Propriety and Prosperity: New Studies on the Philosophy of Adam Smith. Palgrave Macmillan

• Hamowy, Ronald (2008). "Smith, Adam (1723–1790)". Smith, Adam (1732–1790). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; Cato Institute. pp. 470–72. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n287. ISBN 978-1-4129-6580-4. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

• Hollander, Samuel (1973). Economics of Adam Smith. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-6302-0.

• McLean, Iain (2006). Adam Smith, Radical and Egalitarian: An Interpretation for the 21st Century. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-2352-3.

• Milgate, Murray & Stimson, Shannon. (2009). After Adam Smith: A Century of Transformation in Politics and Political Economy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14037-7.

• Muller, Jerry Z. (1995). Adam Smith in His Time and Ours. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00161-8.

• Norman, Jesse (2018). Adam Smith: What He Thought, and Why It Matters. Allen Lane.

• O'Rourke, P.J. (2006). On The Wealth of Nations. Grove/Atlantic Inc. ISBN 0-87113-949-9.

• Otteson, James (2002). Adam Smith's Marketplace of Life. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-01656-8.

• Otteson, James (2013). Adam Smith. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4411-9013-0.

• Phillipson, Nicholas (2010). Adam Smith: An Enlightened Life, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-16927-0, 352 pages; scholarly biography

• McLean, Iain (2004). Adam Smith, Radical and Egalitarian: An Interpretation for the 21st Century Edinburgh University Press

• Pichet, Éric (2004). Adam Smith, je connais !, French biography.[ISBN missing]

• Vianello, F. (1999). "Social accounting in Adam Smith", in: Mongiovi, G. and Petri F. (eds.), Value, Distribution and capital. Essays in honour of Pierangelo Garegnani, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-14277-6.

• Winch, Donald (2007) [2004]. "Smith, Adam". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/25767. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

• Wolloch, N. (2015). "Symposium on Jack Russell Weinstein's Adam Smith's Pluralism: Rationality, Education And The Moral Sentiments". Cosmos + Taxis

• "Adam Smith and Empire: A New Talking Empire Podcast," Imperial & Global Forum, 12 March 2014.

External links• "Adam Smith". Archived from the original on 17 May 2009. Retrieved 17 May 2009. at the Adam Smith Institute

• Works by Adam Smith at Open Library

• Works by Adam Smith at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about Adam Smith at Internet Archive

• Works by Adam Smith at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

• References to Adam Smith in historic European newspapers