Tom Keating

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 9/28/22

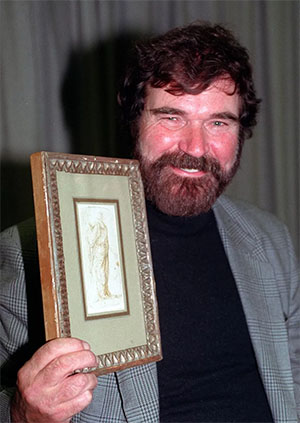

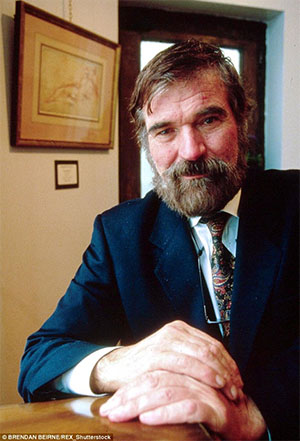

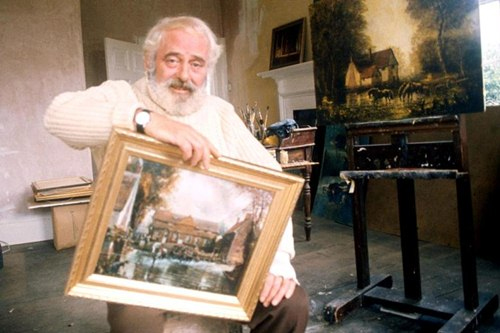

Thomas[1] Patrick Keating[2] (1 March 1917 – 12 February 1984) was an English art restorer and famous art forger who claimed to have faked more than 2,000 paintings by over 100 different artists.[3] The total estimated of the profits of his forgeries amount to more than 10 million dollars in today's value.[4]

Early life

Keating was born in Lewisham, London, into a poor family. His father worked as a house painter, and barely made enough to feed the household. At the age of fourteen, Keating was turned away from St. Dunstan’s College in London.[5] Because his father barely made ends meet, Keating started working at a young age. He worked as a delivery boy, a lather boy, a lift boy and a bell boy before he started working for the family business as a house painter.[5] He was then enlisted as a boiler-stoker in World War II. After World War II, he was admitted into the art programme at Goldsmiths College, University of London. However, he did not receive a diploma, as he dropped out after only two years. In his college classes, his painting technique was praised, while his originality was regarded as insufficient.[5] During Keating's two years at Goldsmiths College, he worked side jobs for art restorers. He even worked for the revered Hahn Brothers in Mayfair. Utilizing the skills he learned through these jobs, he began to restore paintings for a living (although he also had to keep working as a house-painter to make ends meet). He exhibited his own paintings, but failed to break into the art market. In order to prove himself as good as his heroes, Keating began painting in the style of them, especially Samuel Palmer.

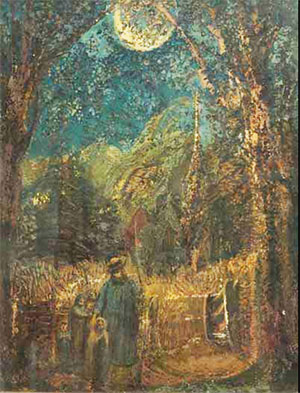

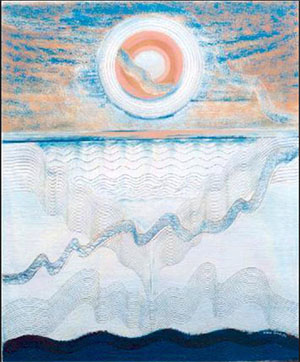

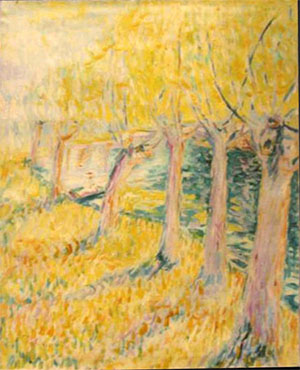

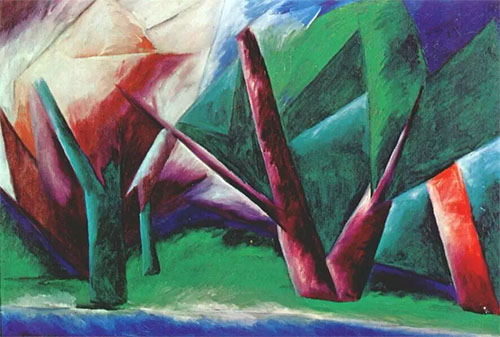

Homage to Samuel Palmer, by Tom Keating

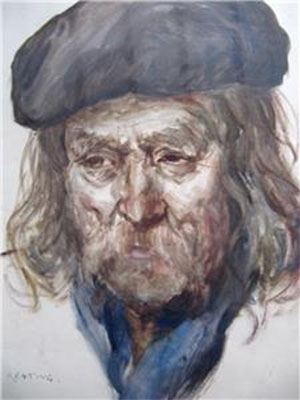

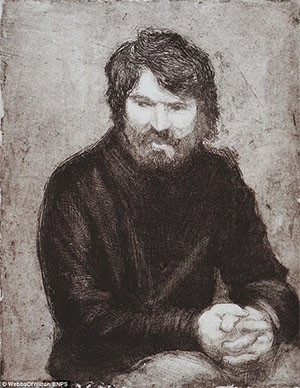

Samuel Palmer, by Tom Keating

Moonlit Dedham, Suffolk, by Tom Keating

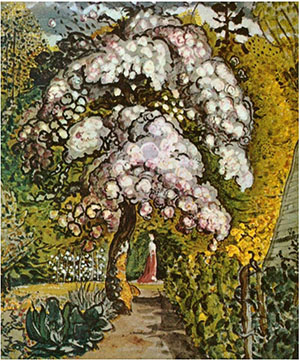

Sussex Landscape, by Tom Keating

In 1963, he met Jane Kelly who would become his lover and partner in spreading and selling his forgeries. However, they separated many years before they were put on trial for the forgeries.

He later married his wife, Hellen, from whom he also separated in his later years. They had a son named Douglas.

Keating studied at London’s National Gallery and the Tate.

Mid-life

After dropping out of college, Keating was picked up by an art restorer named Fred Roberts. Roberts cared less about the ethics of art restoration than other restorers Keating had previously worked for. One of Keating's first jobs was to paint children around a maypole on a 19th-century painting by Thomas Sidney Cooper that had a large hole in it. Most art restorers would have simply filled in the cracks to preserve the authenticity of the painting.[5] His career of forgery stemmed from Roberts' workshop when Keating criticized a painting done by Frank Moss Bennett. Roberts challenged him to recreate one of Bennett's paintings. At first Keating produced replicas of Bennett paintings, but he felt he could do even more. Keating recalls feeling as if he knew so much about Bennett that he could start creating his own works and pass them off as Bennett's.[5] Keating created his own Bennett-like piece, and was so proud of it, that he signed it with his own name. When Roberts saw it, without consulting Keating, he changed the signature to F. M. [Frank Moss] Bennett and consigned it to the West End gallery. Keating did not find out until later, but said nothing.

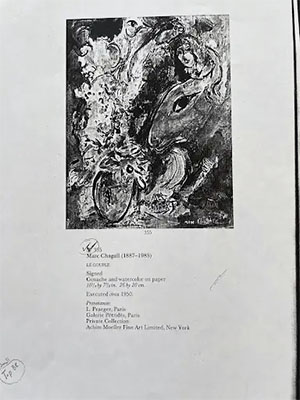

x

According to Keating's account, Jane Kelly was instrumental in circulating his forgeries in the art market. With Palmer being one of his biggest inspirations, he created nearly twenty fake Palmers. Keating and Kelly then decided on the best three forgeries and Kelly took them to gallery specialists for auction.

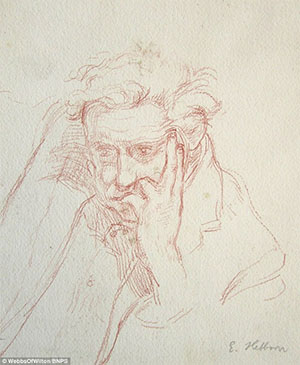

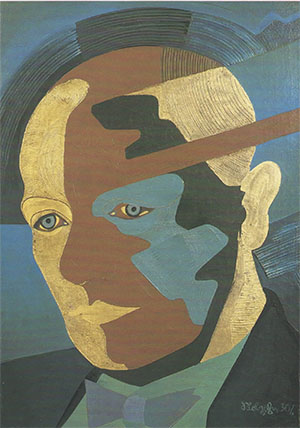

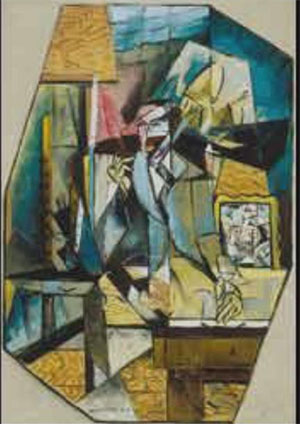

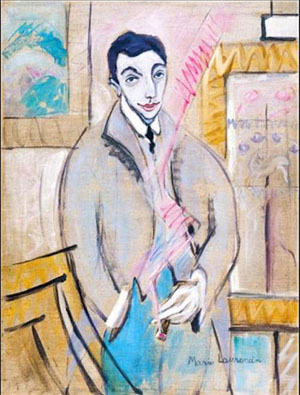

In 1962, Keating counterfeited Edgar Degas' self-portrait.[5]

Self-Portrait, by "Degas", by Tom Keating

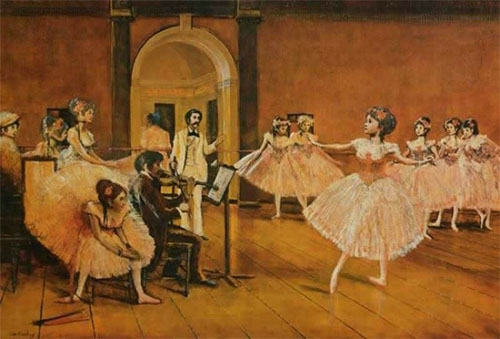

Degas Dancing Class, by Tom Keating

In 1963, he started his own informal school, teaching teenagers painting techniques in exchange for tobacco or second-hand art books.[6] This is where Keating, at the age of 46, met Jane Kelly, at the age of 16, a student of his. Kelly really enjoyed Keating's "class" and convinced her parents to pay Keating a pound/day for full-time instruction.[6] She became especially attached to him and they ultimately became lovers and business partners. Four years later, the two began a life together in Cornwall, where they started an art restoration business.[6]

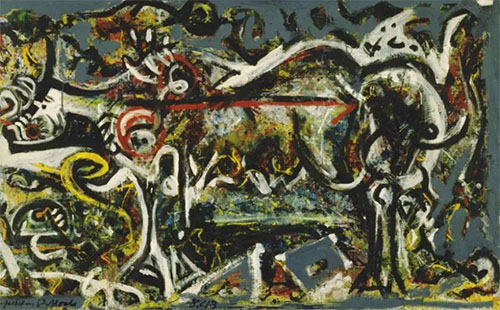

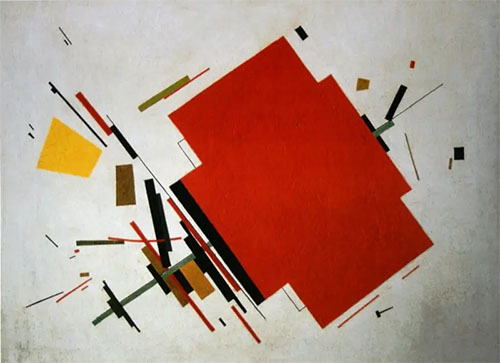

Forger with a cause

Keating perceived the gallery system to be rotten – dominated, he said, by American "avant-garde fashion, with critics and dealers often conniving to line their own pockets at the expense both of naïve collectors and [of] impoverished artists". Keating retaliated by creating forgeries to fool the experts, hoping to destabilize the system. Keating considered himself a socialist and used that mentality to rationalize his actions.[5]

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions they claim maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessarily limited to, the state and capitalism. Anarchism advocates for the replacement of the state with stateless societies or other forms of free associations. As a historically left-wing movement, usually placed on the farthest left of the political spectrum, it is usually described alongside communalism and libertarian Marxism as the libertarian wing (libertarian socialism) of the socialist movement.

-- Anarchism, by Wikipedia

He planted "time-bombs" in his products. He left clues of the paintings' true nature for fellow art restorers or conservators to find. For example, he might write text onto the canvas with lead white before he began the painting, knowing that x-rays would later reveal the text. He deliberately added flaws or anachronisms, or used materials peculiar to the 20th century. Modern copyists of old masters use similar practices to guard against accusations of fraud.

In Keating's book The Fake's Progress, discussing the famous artists he forged, he stated that "it seemed disgraceful to me how many of them died in poverty". He reasoned that the poverty he had shared with these artists qualified him for the job.[5] He added: "I flooded the market with the 'work' of Palmer and many others, not for gain, but simply as a protest against the merchants who make capital out of those I am proud to call my brother artists, both living and dead."[6]

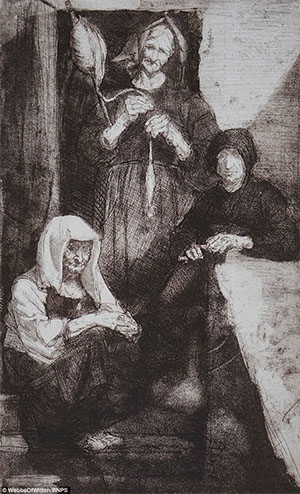

Samuel Palmer paintings

In the early 1970s, 13 paintings by 19th-century English artist Samuel Palmer – the man behind works such as In A Shoreham Garden (pictured) – were put up for auction by art restorer Tom Keating. Palmer, who died in 1881, was particularly hailed for works during what became known as his "Shoreham Period" during which the artist produced landscapes of the Kent village in which he lived between 1826 and 1835.

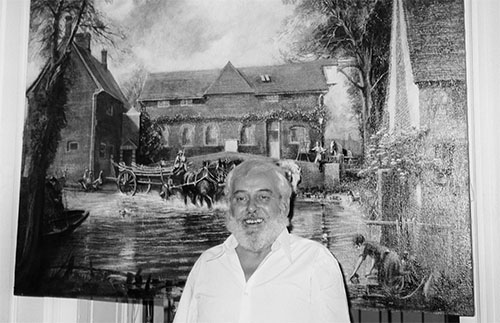

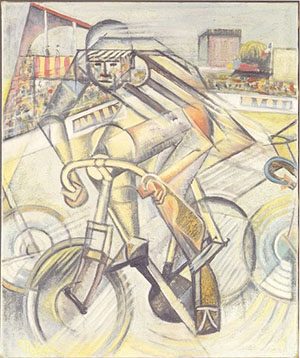

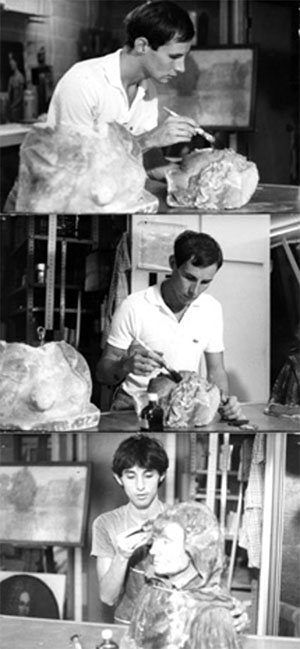

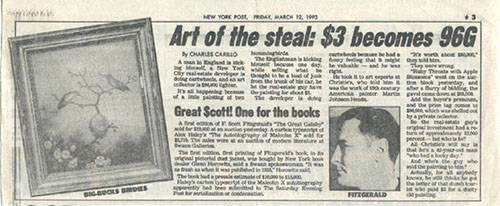

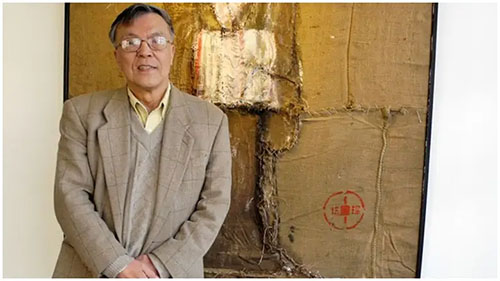

In 1976, The Times journalist Geraldine Norman exposed the Palmer paintings to be fake and Keating (pictured) confessed to having "flooded the market" with versions of works by the Victorian artist and others such as Constable. Keating said he did so as a protest "against the merchants who make capital out of those I am proud to call my brother artists". He was put on trial in 1977 but charges against him were dropped after he was injured in a near-fatal motorcycle crash. He died in 1984.

-- Fake treasure finds that fooled the world, by lovemoney.com

Technique

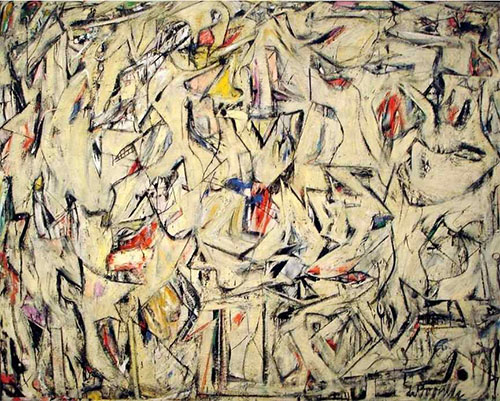

Mastering an artist's style and technique, as well as getting to know the artist very well, was a priority for Keating.

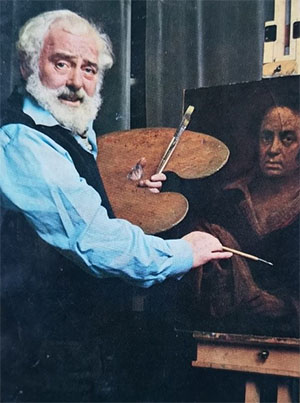

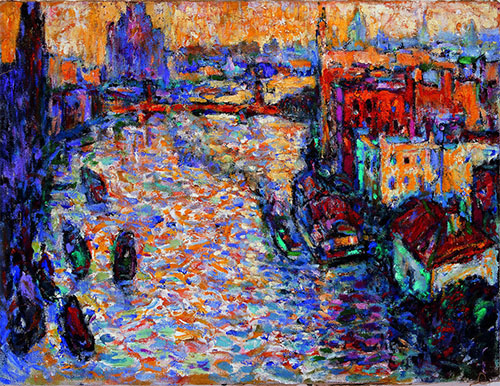

Keating's preferred approach in oil painting was a Venetian technique inspired by Titian's practice, although modified and fine-tuned along Dutch lines. The resultant paintings, while time-consuming to execute, have a richness and subtlety of colour and optical effect, and a variety of texture and depth of atmosphere unattainable in any other way. Unsurprisingly, his favourite artist was Rembrandt.

For a "Rembrandt", Keating might make pigments by boiling nuts for 10 hours and filtering the result through silk; such colouring would eventually fade, while genuine earth pigments would not. As a restorer he knew about the chemistry of cleaning-fluids; so, a layer of glycerine under the paint layer ensured that when any of his forged paintings needed to be cleaned (as all oil paintings need to be, eventually), the glycerin would dissolve, the paint layer would disintegrate, and the painting – now a ruin – would stand revealed as a fake.

Occasionally, as a restorer, he would come across frames with Christie's catalogue numbers still on them. To help in establishing false provenances for his forgeries, he would call the auction house to ask whose paintings they had contained – and would then paint the pictures according to the same artist's style.[7]

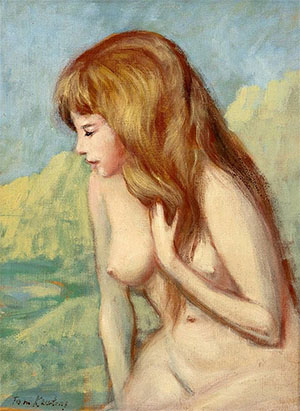

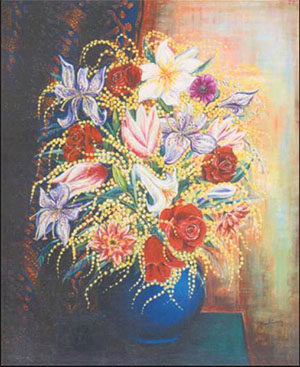

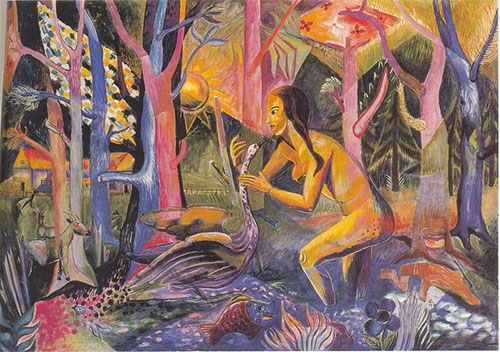

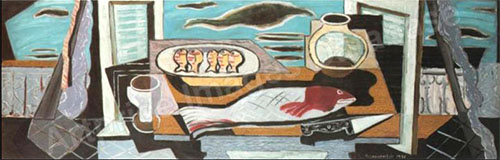

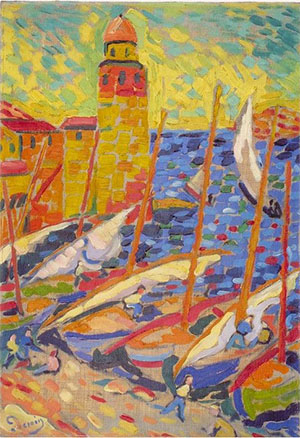

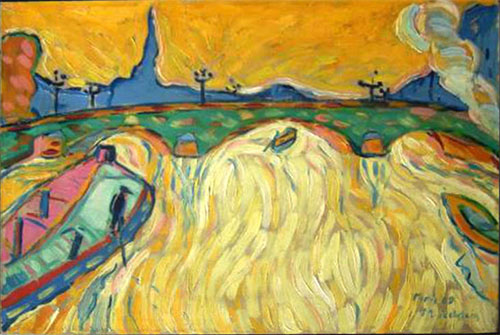

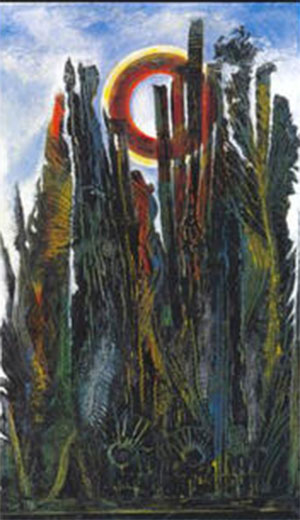

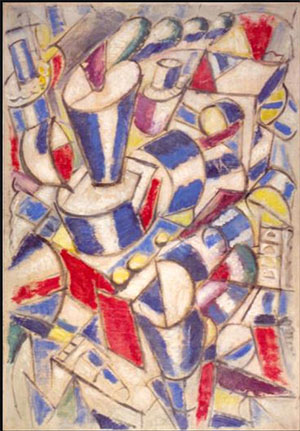

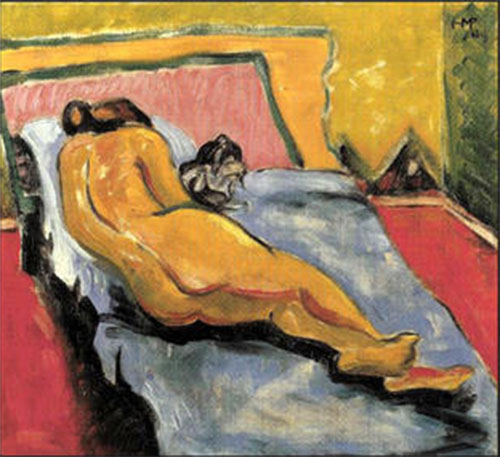

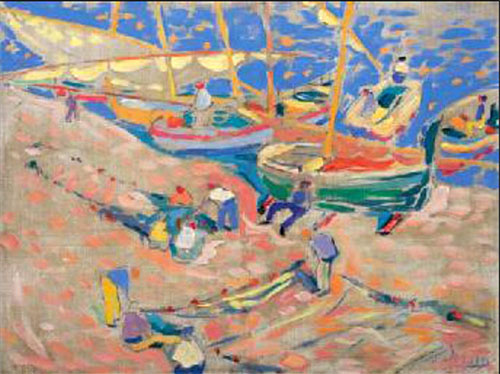

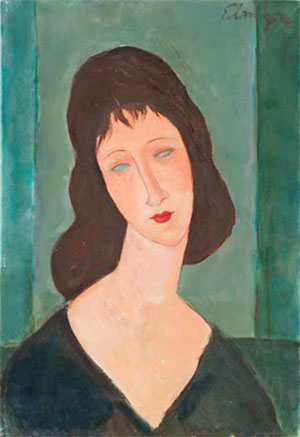

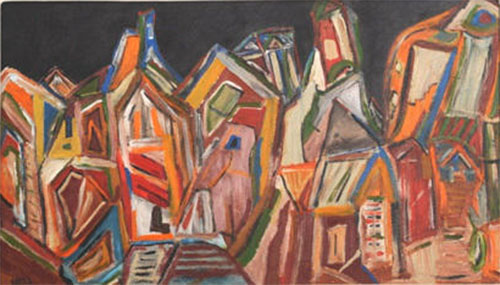

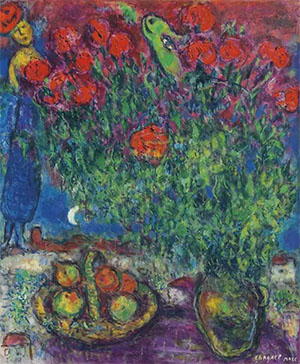

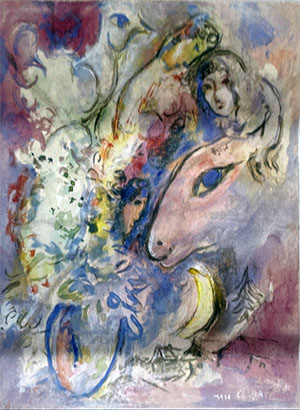

Keating also produced a number of watercolours in the style of Samuel Palmer. To create a Palmer watercolor, Keating would mix the watercolor paints with glutinous tree gum, and cover the paintings with thick coats of varnish in order to get the right consistency and texture.[6] And oil paintings by various European masters, including François Boucher, Edgar Degas, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Thomas Gainsborough, Amedeo Modigliani, Rembrandt, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Kees van Dongen.

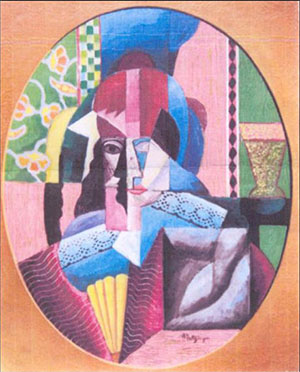

Kees Van Dongen, by Tom Keating

Keating's "Sexton Blakes"

Sexton blake is a term coined in the UK from the name of a fictional detective, comparable to Sherlock Holmes. In rhyming slang, the term means "fake". As usual, for a short time after its creation, a slang term has limited currency as it is known only to a few people, typically those in the criminal underworld. So Keating initially referred to all of his forgeries as Sextons.[1]

Revealing the forger

River landscape in the Porczyński Gallery in Warsaw, signed as Alfred Sisley, is claimed to be Keating's forgery

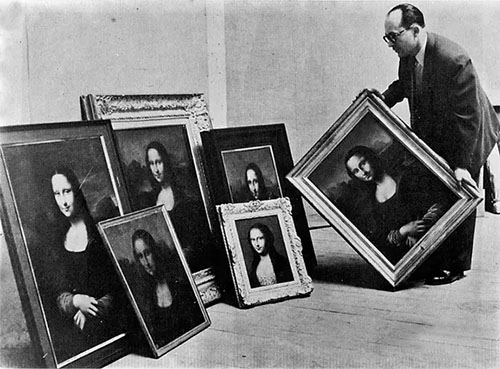

In 1970, auctioneers noticed that there were thirteen Samuel Palmer watercolour paintings for sale – all of them depicting the same theme, the village of Shoreham, Kent.

Geraldine Norman, the The Times of London's salesroom correspondent, looked into the 13 Palmer watercolors, sending them to be scientifically tested by a renowned specialist, Geoffrey Grigson. After careful inspection, she published an article in summer 1976 declaring these "Palmers" to be fake.[8] Norman was sent tips as to who forged these paintings, but it was not until Jane Kelly's brother met up with Norman and told her all about Keating, that she found out the truth. Soon after, she drove out to the house that Kelly's brother had told her about, and met Keating. Keating welcomed her inside and told her all about his life as a restorer and artist, not discussing his life as a forger. He also spent much of the time ranting about his fight against the art establishment as a working-class socialist.[6] A little over a week after their meeting (and a month after the first article), The Times published a further article written by Norman, writing about Keating's life and the many allegations of forgery against him.[8] In response, Keating wrote: "I do not deny these allegations. In fact, I openly confess to having done them." He also declared that money was not his incentive.[6] Though Norman was the one to expose him, Keating did not feel resentment towards her. Instead he said that she was sympathetic, respectful of his radical politics, and appreciative of him as an artist.[6]

When an article published in The Times discussed the auctioneer's suspicions about their provenance, Keating confessed that they were his. He also estimated that more than 2,000 of his forgeries were in circulation. He had created them, he declared, as a protest against those art traders who get rich at the artist's expense. He also refused to list the forgeries.

The trial

After Keating and Jane Kelly were finally arrested in 1979, and both accused of conspiracy to defraud and obtaining payments through deception amounting to £21,416,[6] Kelly pleaded guilty, promising to testify against Keating. Conversely, Keating pleaded innocent, on the basis that he was never intending to defraud, rather he was simply working under the masters' guidance and in their spirit.

Dionysius, or Pseudo-Dionysius, as he has come to be known in the contemporary world, was a Christian Neoplatonist who wrote in the late fifth or early sixth century CE and who transposed in a thoroughly original way the whole of Pagan Neoplatonism from Plotinus to Proclus, but especially that of Proclus and the Platonic Academy in Athens, into a distinctively new Christian context.

Though Pseudo-Dionysius lived in the late fifth and early sixth century C.E., his works were written as if they were composed by St. Dionysius the Areopagite, who was a member of the Athenian judicial council (known as ‘the Areopagus’) in the 1st century C.E. and who was converted by St. Paul. Thus, these works might be regarded as a successful ‘forgery’, providing Pseudo-Dionysius with impeccable Christian credentials that conveniently antedated Plotinus by close to two hundred years. So successful was this stratagem that Dionysius acquired almost apostolic authority, giving his writings enormous influence in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, though his views on the Trinity and Christ (e.g., his emphasis upon the single theandric activity of Christ (see Letter 4) as opposed to the later orthodox view of two activities) were not always accepted as orthodox since they required repeated defenses, for example, by John of Scythopolis and by Maximus Confessor. Dionysius’ fictitious identity, doubted already in the sixth century by Hypatius of Ephesus and later by Nicholas of Cusa, was first seriously called into question by Lorenzo Valla in 1457 and John Grocyn in 1501, a critical viewpoint later accepted and publicized by Erasmus from 1504 onward. But it has only become generally accepted in modern times that instead of being the disciple of St. Paul, Dionysius must have lived in the time of Proclus, most probably being a pupil of Proclus, perhaps of Syrian origin, who knew enough of Platonism and the Christian tradition to transform them both. Since Proclus died in 485 CE, and since the first clear citation of Dionysius’ works is by Severus of Antioch between 518 and 528, then we can place Dionysius’ authorship between 485 and 518–28 CE. These dates are confirmed by what we find in the Dionysian corpus: a knowledge of Athenian Neoplatonism of the time, an appeal to doctrinal formulas and parts of the Christian liturgy (e.g., the Creed) current in the late fifth century, and an adaptation of late fifth-century Neoplatonic religious rites, particularly theurgy, as we shall see below.

It must also be recognized that “forgery” is a modern notion. Like Plotinus and the Cappadocians before him, Dionysius does not claim to be an innovator, but rather a communicator of a tradition. Adopting the persona of an ancient figure was a long established rhetorical device (known as declamatio), and others in Dionysius’ circle also adopted pseudonymous names from the New Testament. Dionysius’ works, therefore, are much less a forgery in the modern sense than an acknowledgement of reception and transmission, namely, a kind of coded recognition that the resonances of any sacred undertaking are intertextual, bringing the diachronic structures of time and space together in a synchronic way, and that this theological teaching, at least, is dialectically received from another. Dionysius represents his own teaching as coming from a certain Hierotheus and as being addressed to a certain Timotheus. He seems to conceive of himself, therefore, as an in-between figure, very like a Dionysius the Areopagite, in fact. Finally, if Iamblichus and Proclus can point to a primordial, pre-Platonic wisdom, namely, that of Pythagoras, and if Plotinus himself can claim not to be an originator of a tradition (after all, the term Neoplatonism is just a convenient modern tag), then why cannot Dionysius point to a distinctly Christian theological and philosophical resonance in an earlier pre-Plotinian wisdom that instantaneously bridged the gap between Judaeo-Christianity (St. Paul) and Athenian paganism (the Areopagite)? [For a different view of Dionysius as crypto-pagan, see Lankila, 2011, 14–40.]

-- Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, by Kevin Corrigan L. Michael Harrington, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, first published Mon Sep 6, 2004; substantive revision Tue Apr 30, 2019, Copyright © 2019 by Kevin Corrigan and L. Michael Harrington

The charges were eventually dropped due to his poor health after he was severely injured in a motorcycle accident. He then contracted bronchitis in the hospital, which was exacerbated by a heart ailment and pulmonary disease, leading the doctors to believe that he was not going to survive. The prosecutor dropped the case, declaring nolle prosequi.[6] Since Kelly had already pleaded guilty, she still had to serve her time in prison. However, Keating served no time, and shortly after the charges were dropped, Keating's health improved. Soon after, Keating was asked to star in a television show about the techniques needed to paint like the masters.

Aftermath

The same year Keating was arrested (1977), he published his autobiography with Geraldine and Frank Norman. A 2005 article in The Guardian stated that after the trial was halted, "the public warmed to him, believing him a charming old rogue."[3] Years of chain smoking and the effects of breathing in the fumes of chemicals used in art restoring, such as ammonia, turpentine and methyl alcohol, together with the stress induced by the court case, had taken their toll. Through 1982 and 1983 Keating rallied, however, and although in fragile health, he presented television programmes on the techniques of old masters for Channel 4 in the UK.[3][9]

A year before he died in Colchester at the age of 66, Keating stated in a television interview, that, in his opinion, he was not an especially good painter. His proponents would disagree. Keating is buried in the churchyard of the parish church of St Mary the Virgin at Dedham (a scene painted numerous times by Sir Alfred Munnings), and his last painting, The Angel of Dedham, is to be found in the Muniment Library of the church.[7][10][11]

The grave of Tom Keating in the churchyard of St Mary the Virgin, Dedham, Essex.

Even when he was alive, many art collectors and celebrities, such as the ex-heavyweight boxer Henry Cooper, had begun to collect Keating's work. After his death, his paintings became increasingly valuable collectibles. In the year of his death, Christie's auctioned 204 of his works. The amount raised from the auction was not announced, but it is said to have been considerable. Even his known forgeries, described in catalogues as "after" Gainsborough or Cézanne, attain high prices. Nowadays, Keatings sell for tens of thousands of pounds.

And perhaps even more interesting, there are fake Keatings. The 2005 Guardian article states, "Dodgy paintings in Keating's original style, proudly bearing what-looks-like his signature, are finding their way into the market. If they manage to fool, they can claim £5,000 to £10,000. But if uncovered they are virtually worthless, much like Keating's 20 years ago. If you can pick them up for next to nothing, they may be a better investment than an original Keating counterfeit."[3]

Tom Keating on Painters (television show)

After Keating's legal suit was dropped, he was asked to star in a television show called Tom Keating on Painters. The show started airing in 1982 at 6:30 p.m. on weekdays to attract a family audience. On this show, Keating demonstrated how to paint like the masters, illustrating the techniques and processes of painting like artists, such as Titian, Rembrandt, Claude Monet, and John Constable.[5][12]

In popular culture

In the 2002 film The Good Thief Nick Nolte's character claims to own a painting Picasso did for him after losing a bet, when it is exposed as a fake he claims it was painted for him by Keating after meeting in a betting shop.

The fourth track, titled "Judas Unrepentant", on progressive rock band Big Big Train's 2012 album English Electric (Part One) is based on the life of Keating as an artist. According to the blog of Big Big Train vocalist David Longdon, the song walks through Keating's artistic life from his time as a restorer to his death and posthumous fame.[13]

Further reading

• Tom Keating, Geraldine Norman and Frank Norman, The Fake's Progress: The Tom Keating Story, London: Hutchinson and Co., 1977.

• Associated Press obituary for Tom Keating

• Keats, Jonathon, Forged: Why Fakes Are the Great Art of Our Age, New York: Oxford University Press., 2013. (Excerpt on Tom Keating published by Forbes, 13 December 2012).

• Paci, P., "A Forger's Career, Tom Keating – UK," in Masters of the Swindle: True Stories of Con Men, Cheaters & Scam Artists, edited by Gianni Morelli and Chiara Schiavano, Milano, Italy: White Star Publishers, 2016, pages 180–84.

References

1. "Tom Keating: Art Fraud". JAQUO Lifestyle Magazine. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

2. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

3. MacGillivray, Donald (2 July 2005). "When is a fake not a fake? When it's a genuine forgery". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

4. "Authentication in Art Unmasked Forgers".

5. Keats, Jonathon. "Masterpieces For Everyone? The Case Of The Socialist Art Forger Tom Keating [Book Excerpt]". Forbes. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

6. Keats, Jonathon. "The Ultimate In Reality TV? Try Televised Art Forgery. [Book Excerpt #2]". Forbes. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

7. "Tom Keating, 66, a Painter; Gained Fame as Art Forger". The New York Times. 14 February 1984.

8. Magnusson, Magnus (2007) [2006]. Fakers, Forgers & Phoneys. Edinburgh: Mainstream. pp. 32–6. ISBN 978-1-84596-210-4.

9. Landesman, Peter (18 July 1999). "A 20th-Century Master Scam". The New York Times.

10. "Soaring beauty of village church". Gazette. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

11. Cook, William. "Dedham Vale | The Spectator". http://www.spectator.co.uk. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

12. Keats, Jonathon. "Masterpieces For Everyone? The Case Of The Socialist Art Forger Tom Keating [Book Excerpt]". Forbes.

13. Longdon, David (5 August 2012). "Judas Unrepentant". David Longdon Blog. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

********************

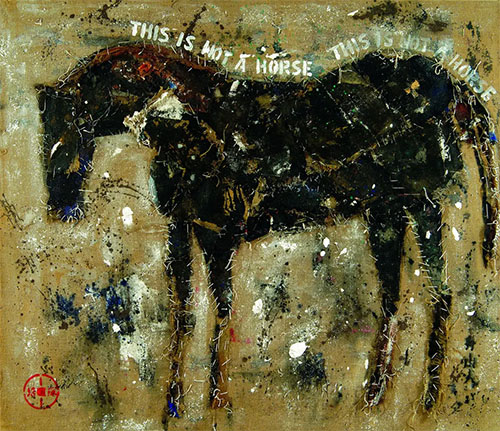

When a fake is not a Keating: It may be by Samuel Palmer, by a master faker, or by an unknown. Who is the creator of a suspect watercolour at the Royal Academy?

by Geraldine Norman

UK Independent

Sunday 14 March 1993 00:02

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

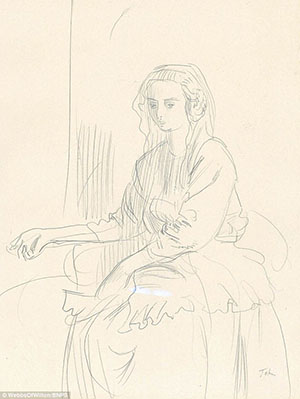

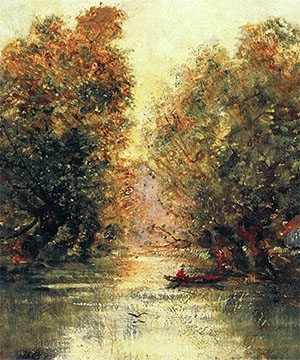

QUESTION: when is a Samuel Palmer not a Samuel Palmer? Answer: when it's done by Tom Keating. Or that is what art historians would nowadays have one believe. 'Did you know there was a Tom Keating at the Royal Academy?' a respected art historian asked me on the phone the other day, after we had discussed something quite different. I didn't. I didn't even know that one of the Palmers in the 'Great Age of British Watercolours' exhibition at the Royal Academy was under suspicion of being a fake.

Samuel Palmer brought an extraordinary mystical vision to landscape painting for about six years around 1830. The inspiration faded and, though he imitated it later in life, he never recaptured his youthful inspiration. The drawings remained in his family and virtually unknown until an exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum in 1926 of 'Samuel Palmer and other Disciples of William Blake'. It had a huge impact on British artists and connoisseurs; the artists imitated his work and the connoisseurs bought the watercolours from his son, A H Palmer.

In the early days his drawings were not expensive and no one is known to have started faking his work until Tom Keating took it up in the 1960s and 1970s - when prices had risen. But that is not to say that others did not try making Palmers, either for fun or to earn a few irregular pounds. Indeed, in my opinion the suspect painting at the Royal Academy - a very orange watercolour called Harvesters by Firelight - makes it clear that someone did.

I have a special interest in Tom Keating, since I was the journalist who unmasked him as a picture-faker back in 1976 - on account of his fake Samuel Palmer watercolours. So I rang round the Palmer buffs. 'When was it that your friend started out?' laughed Martin Butlin, former keeper of the British collection at the Tate. 'We know this one was in existence by 1951. Was Keating at work by then?' Keating had just left art school by 1951 and was already copying Old Masters but not, to my knowledge, making Palmers. I found a couple of Keating Palmers tucked away at the back of a drawer. One is reproduced here along with Harvesters: a clear demonstration, in my view, that the watercolour in the R A show is not by Keating. The way the foliage is treated is, perhaps, the most obvious giveaway. Keating indicates leaves by making quantities of individual brush strokes. Whoever did the R A drawing has used a black outline for the shape of the trees and filled it in with wash.

Harvesters by Firelight, 1830, Pen and black ink with watercolor and gouache on wove paper, 11 5/16 × 14 7/16 in, 28.7 × 36.7 cm, by Samuel Palmer

That puts paid to the Keating idea. But having a suspect Palmer in the Royal Academy show - acknowledged as such by the exhibition's organiser - is a very unusual bit of miscalculation. As far as I can make out from the embarrassed participants, no one realised it wasn't by Palmer until the catalogue was written and the show was on the walls.

The drawing belongs to the National Gallery in Washington, which received it as a gift from Paul Mellon in 1986. Mellon, who inherited one of the largest fortunes in America, has given the National Gallery - which was founded by his father - more than 800 pictures. It was not difficult for one fake to sneak in among them.

Mellon himself is a passionate anglophile and has formed the most important private collection of British art anywhere in the world, even rivalling the Tate. It is now mostly housed at the Yale Center for British Art. He bought the 'Palmer' watercolour at Christie's in 1981 for pounds 77,000 through his friend and agent John Baskett, then a Bond Street dealer. 'I've always thought it was a Palmer,' John Baskett told me last week. 'There was no doubt at the time.' Mellon's reaction to my enquiry was 'No comment'.

It was not until 1988 that a catalogue raisonne of Samuel Palmer's work - a catalogue, that is, which lists all known Palmers and discusses them - appeared. Raymond Lister, its author, told me: 'I included Harvesters because I felt it couldn't exactly be rejected as a Palmer - but I'm not as convinced as I was. It could be an original that someone's played about with. I don't think the red figure in front is by Palmer.'

There is an inscription on the back, Lister points out, which is particularly suspicious. It is supposed to be in the hand of Palmer's son, who did inscribe several drawings; if it was not written by him, it must have been written by someone who was consciously trying to turn the picture into a Palmer.

The inscription explains that the wild orange glow over the scene is: 'The reflection of one of the incendiary fires, fires in Kent, I think about 1830 done I think the next day. The building is, I think Ightham Mote. A H P. Subject the harvesters hurrying away the last of the harvest.' Lister wrote in his catalogue: 'The building is not Ightham Mote. Such an indecisive statement is uncharacteristic of A H Palmer. Moreover, it does not make sense: it would have been unnecessary to 'hurry away' the last of the harvest for the 1830 incendiary attacks were aimed against stacks and barns and not against growing crops'.

It is not entirely clear when doubts about the painting began to surface. 'I remember considerable enthusiasm for it when we had it for sale in 1981,' Anthony Browne of Christie's told me. However, both Martin Butlin and his successor at the Tate, Andrew Wilton, tell me they did not think it was by Samuel Palmer at the time.

Andrew Wilton is the curator of the Royal Academy show and says that the watercolour slipped in because the exhibition had to be mounted in such a hurry - he only had six months to put it together, from start to finish.

'The Palmers we wanted were not available,' Wilton said. 'I rather hoped that as the National Gallery in Washington offered it as one of the things they were happy to lend, they had sorted out the attribution.' No such thing: 'I first heard of the doubts when the Royal Academy rang me in Italy two weeks ago,' Andrew Robison, the National Gallery's curator of drawings, told me. 'If it's not by Palmer, we won't have any problem about changing the attribution but I don't yet understand what's wrong.' Piers Rodgers, secretary of the Royal Academy, maintains that the argument over the attribution is not yet resolved. 'Scholars have been discussing it for ages,' he said. 'We knew that when we put it in the show.'

The inclusion of the drawing in the exhibition has been hard luck on the pundits. Simon Jenkins, former editor of the Times, described Palmer's 'idylls of the gloaming' in a column about the Academy show, pointing especially to 'his brilliant Harvesters by Firelight'. Brian Sewell in the Evening Standard illustrated the painting in colour to demonstrate what he thought of English watercolours - but saved his reputation as a connoisseur by describing it as 'a sickening confection of glutinous marmalades coarse cut'.

*************************