Who's Who In the Lyceum [Excerpt]

Edited by A. Augustus Wright

Including a Brief History of the Lyceum by Anna L. Curtis and How to Organize and Manage a Lyceum Court by Laurence Tom K. Kersey

© 1906 by Pearson Bros.

"A man cannot with propriety speak of himself, except he relates simple facts; as, 'I was at Richmond'; or, what depends on mensuration; as, "I am six feet high': but he cannot be sure he is wise, or that he has any other excellence."

-- Dr. Johnson

Foreword.

Tools and the Man

"Who's Who in the Lyceum" is a set of tools, made and truly tempered, for work never yet wrought adequately. Whatever may be said or thought of "The Man With a Hoe," it is certain he is in better case than "The Man Without a Hoe." The crop that is yet to be harvested from the broad acres of the Lyceum field, will depend very largely upon the way these tools — here handed to the man — are handled by the man.

* * *

The Word Lyceum

The word Lyceum notably exemplifies and illustrates the fact that language grows. To-day the word includes what yesterday was absent; to-morrow it will include what to-day knows not.

As to inclusions and exclusions for to-day, clearly the word Lyceum excludes the theater and includes the drama; it excludes whatever is specifically and only theatric, and it includes whatever is specifically and wholly dramatic. It excludes whatever appeals solely to the eye or to the other senses — as senses; for example, all the gorgeous paraphernalia of usual perception ordinarily assumed at the Play to represent Life as it is, but whose very gorgeousness blinds the eye to see beneath the object to the subject, the word Lyceum excludes all such things of the senses; it includes whatever action, word or appearance reaches the soul through valid psychical appeals to the creative imagination. Life is dramatic, not theatric; of the essence and not of the form of things, life is drama. Hence the drama finds its first, noblest and most complete expression, not at the Theater, but upon the Lyceum Platform. Here are won already, and here are yet to be doubly won, the greatest triumphs of the unfettered imagination.

"Who's Who in the Lyceum" lays emphasis upon the declaration that whatever belongs indisputably to spiritual aesthetics — the realm of Life's most intimate and most significant drama — belongs to the Lyceum; whatever does not, belongs elsewhere.

Clearly, too, and for the same reason, the word Lyceum excludes the vaudeville, the circus, the amusement in which the performer is but a performer, whatever or whoever is "the whole show"; and, in truth, it excludes every sort of entertainment whose roots and branches and fruit are evidently of the earth earthy.

A Letter

"I am merely a society entertainer, having no particular connection with the so-called Lyceum movement; therefore your volume will be complete without my biographical data."

Excellent. This gentleman is commendable for his perspicacity and for the frankness of his avowal as well as for the exactness of his identification of the Lyceum, and of — himself.

In the present work the word Lyceum includes particularly all University Extension Lectureships, with all scientific, aesthetic, literary, educational and similar Lectureships, with interpretative Lecture-Recitals, together with Symphonic or even Solo Concerts, Readings, Dramatic Monologues, Dramatic Recitals of entire Dramas, and similar entertainments aiming at ends strictly aesthetic, artistic and moral.

***

Standards of Eligibility.

As to eligibility to a place in "Who's Who in the Lyceum," in instances where there is any doubt — as to this man or as to that woman — eligibility is determined, though not exclusively, by satisfactory answers to three principal questions:

(a) Is the candidate pursuing Lyceum work as an artistic vocation, or merely as a negligible avocation?

(b) On the average, how many engagements does he fill annually?

(c) What is the nature, and, to some indicative extent, what is the ideal of his work?

At times this last standard brings us perilously near to the necessities of exercising judicial functions, notwithstanding "Who's Who" is a "record, not an estimate," a census of individuals rather than an appreciation of persons. Still, no injustice is done to any, since all are brought alike to the same standards.

Significance of These Standards.

The task of determining these standards, both as to their number and as to their significance, has been exceedingly difficult, while the rigid application of them has been occasionally well-nigh impracticable.

Probably some persons are included in the published list whom some would not admit. But where liberality has seemed a virtue of necessity, the interpretation of these standards has been liberal, particularly in instances where, evidently, genius is at once young, vigorous and crescent.

Let the brilliant luminaries of the Lyceum heavens never forget that all the light of the nightly firmament radiates not from the fixed stars alone.

Restricted Scope of This Work

"Who's Who in the Lyceum" is neither a Dun nor a Bradstreet. It is not a clearing house for decayed or decaying talent or bureaus. It is not a "Fads and Fancies," nor yet a "Dictionary of Biography." Manifestly there is herein no place for the exploitation of expert verdicts, or of popular verdicts, good, bad or indifferent. No lecturer is alike good, bad or indifferent in all places and at all times. Some of the times and many of the places are themselves also g. b. and i.; sometimes I.

Some workers have their work in their hearts, and some have their hearts in their work, and some show the marks of both estates co-ordinate. But, as to who these are, this work was made to make no sign. This work doesn't know. It might be desirable — certainly it must be desirable — for a committee to know, in advance of the Bureau's paternal suggestions, whether So-and-So, "elocutionist," is first of all a genuine woman, with a real, a warm, a living soul within her, and next is also capable — capable of working the miracles of interpretation, yea, of artistic and of Aesthetic creation, or whether, in the last analysis she is to be gibbeted as only a frivolous mixture of millinery and Delsarte. And whether So-and-So, lecturer, is artist or only artisan; whether with him lecturing is an aesthetic art, or merely a piece of stark commercial handcraft; whether, for intellectual stimulus, for artistic inspiration, for ethical suggestiveness, and for general healthful impressiveness, said So-and-So is clearly ratable at the n power, or only at the n.g. power. But on these points, and on all similar points, this work knows naught.

* * *

Caveat

Any adverse criticisms of this work's incompleteness, of its colorlessness, of its character as mere chronicle, of the brevity and condensed quality of its sketches, are vanquished easily by a fair presentation of its aim, its scope and its utilities. Indeed, all such criticisms are routed with a single sentence: "This work is a Who's Who, not a What's Who!"

Wherein this Work is Authoritative.

Since authority ever rests on truth, and truth never rests on authority, this work has been made first of all and last of all, true. If, in the nature of the case, it must be inadequate, and incomplete, still it is true, accurate, and therefore trustworthy. Time, money and sleepless care, without stint, have been expended to secure accuracy in every statement. In all instances where a published record for any reason challenged attention, by verifying the facts we have avoided perpetuating a clerical error, or repeating some one's original blunder.

As a matter of fact, no sketch is published against consent, or without consent, and with but few exceptions each sketch has received the O.K. of the subject himself.

* * *

Utilities of this Work

To Talent this work is an introduction to "men of like passions." Each artist will now be able to cultivate still further his own acquired, if not achieved modesty by a contemplation of others'. Each artist's claims will take on a fresh significance as he notes what others like himself are doing. It is a real comfort to any one to know that on the shores of any great enterprise he is not — alone.

To Bureau Managers it furnishes reliable data — data of an intimate quality; data such as would cost the individual Bureaus time, toil and money beyond their thought. Now, and for the first time, they may learn what other Bureaus are doing, or are trying to do.

To Committees it is indeed a boon. It widens their scope of observation; it shows planets, suns, fixed stars, and even nebula, in the heavens Above, or on the horizon, that the * * * * Bureau's telescope never showed.

It is true that the information published — regarding some stars — is a trifle nebulous, but that fact is itself revelatory to the eye of the astute Committee.

It is also true this information is never intimate; in the scope of this work it could not be intimate; yet is it sufficient to indicate to any Committee the direction in which such information may be sought wisely.

To Editors, Librarians, Educators, Statesmen, Officials of the Public Service, and to others, this work affords utilities of immediate value. Moreover, it will even create utilities not yet discerned, precisely as demand creates supply and supply creates demand.

* * *

The Business Side

The business side of "Who's Who in the Lyceum" — as a venture in publication — merits a brief paragraph. Without other solicitation than that couched in the bare terms of announcement, the de luxe edition has been over-subscribed, and the general edition about fully subscribed, in advance of publication.

This result is gratifying to publishers and to the Editor, not more on business grounds than on the consideration that a discerning Lyceum Public Opinion has thus already passed favorable judgment upon the enterprise.

* * *

Curios

In the compilation of this work the inevitable tedium of routine correspondence has been relieved at times by letters bearing suggestive comments, or containing caustic criticisms, or else revealing the essential humor of situations the writers never saw.

One gentleman, a distinguished prelate of a great church — his sketch is found herein — declares his opinion on a certain matter thus: "The Lecture platform ought to stand for a message and not for a sing-song repetition of the only effort of which a man has been capable."

Talent will do themselves justice, if not more, by writing this gentleman, quoting "let the galled jade wince," and adding (?) — the rest of the sentence.

Another writer says, with charming naivete: "My work has made me, and not any Bureau."

Through the mists of ambiguity that cloud this sentence one can dimly discern the intention of the writer. Doubtless such as he are famous, not because they are on the platform, nor yet because the platform is on them, but the platform is famous because they are on it, or, in spite of it.

But the Kohinoor in this cabinet of Curios remains to outshine these other gems. To what a distance the malefic influence of "Fads and Fancies" has already traveled may be read between two lines of another letter. True, this letter was written by one, it must be confessed, the absence of whose name does not utterly ruin the work. And yet, such is the spirit of the man that this letter is one whose very paper — between said two lines — crimps and crumples itself rattlingly, phenomenally, and as if instinctively, with the writer's righteous indignation at once judicial and suspicious: "I will never allow my name to be used for purposes of advertisement."

Doubtless he scents a bribe! But the spotlessness of this man's virtuous purpose, not to say the unspotability of this man's virtuous purpose, affords a white background against which the sunlight of any publicity shows black. Let all Talent beware.

Queries

An inspection of the data furnished herein, whether it be casual or not, will suggest certain important queries. Why are so many people booking their own dates without the aid of any Bureau? Is it because Bureaus and Talent do not understand, or is it because they do understand each other?

Again, What is the average duration of popularity in lectures as compared with entertainments? What is the Bureau's answer? And what the Committee's answer?

Again, Why are there so few good preachers who are also equally good lecturers? Is it because preachers do not know the essential difference between the functions of a sermon and those of a lecture? Is it because they think a lecture is necessarily less important and less valuable than a sermon? Is it because traditional homiletics has atrophied their sense of humor?

Again, What are the generic characteristics of the lecture themes treated upon the lecture platform of to-day? And what principles may we safely use in identifying the sweep of Lyceum lecture currents to-day?

Again, Why do so many United States Congressmen, so many Statesmen, Historians, Travelers, Scientists, Political Economists, Philosophers, Clergymen, all of the very first class, ascend the Lyceum platform? And why are there not many more of these same classes ascending the Lyceum platform?

The Future of the Lyceum is in the Hands of the Great Personalities.

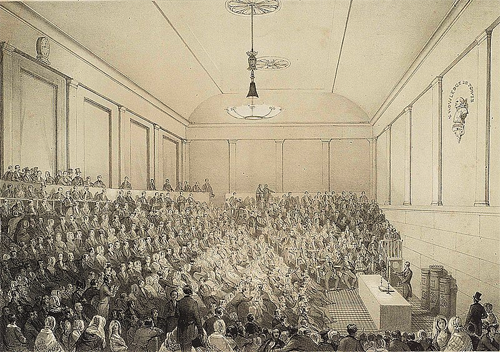

The great personalities who are to dominate the Lyceum of the immediate future are not talkers simply, nor persons of culture only, nor merely people of taste, though it be at once delicate, delicious, exquisite. They are more, and they must be more. They are moral as well as intellectual giants. Manifestly, even in the midst of the commercial, the industrial, the political, the materialistic chaos of the times, these men are present as brooding spirits, gifted out of infinity and hence out of eternity; gifted with architectonic capabilities and skill.

These men are gifted with the reformative potencies of philanthropy, noble, altruistic, self-effacing, self-sacrificial. But far beyond this these men are gifted with that vaster dynamic — the preformative genius of creativeness; they do things, and they do new things; they are workers, and they work all sorts of righteousness; they are genuine poets, weaving and working life's words into psalms and paeans, fitting every tongue; they are creators — creators of a new cosmos, ideal, yet coming down out of the heavens of truth, first into the vision, next into the ambition, and then into the enthralled affection of mankind.

These men are creators, listening to whom all auditors feel supremely that the fires of artistic passion, the nice discernments of aesthetic wisdom, and the mighty sanctions of ethics exist in these creators plenarily, formatively and co-ordinately. These men are creators; they actually create new intellectual, aesthetic and even ethical situations in the imagination of their auditors; they take little words, and big, and into these they breathe the breath of all kinds of life, and thus are able to restate life in newly-created forms and in newly-ordered scopes; and then these same creators, these who thus have re-stated life, are able, with equal ease, to interpret this their own divine exegesis of life, in forms of truth, in lives of beauty, and in the saving terms of righteousness. To these creators, these great personalities, the Lyceum calls to-day. To all others the Lyceum is dumb, yea, and makes no sign.

A Brief History of the Lyceum

by Anna L. Curtis

The Lyceum field has no mean acreage. Its plateaus and its vales stretch far beyond the vision. Yet, in any general survey thereof, and from any point of view, certain mountain peaks arrest the eye and dominate the horizon.

Trustworthy data, recently gathered, show that the number of established Lyceum lecture courses in the United States— courses in which one ticket is sold for the entire season, courses which now are regularly held from year to year — cannot be far from six thousand. This statement relates to courses of Lyceum lectureships alone, and takes no cognizance of the numberless single lectures, concerts, artistic and aesthetic entertainments, provided by local enterprise or by Lyceum bureaus.

LOWELL INSTITUTE, BOSTON

In scrutinizing the details of this general survey, the free public lectureships, provided on permanent foundations, — like the Lowell Institute Courses in Boston, or the Peabody Institute Courses in Baltimore, — must be particularly noted. These lectureships are rapidly increasing in number in every part of the land, and are constantly increasing in their efficient ministry to our national intellectual vigor. Moreover, by their strictly formal character and by their profound philosophic and inspirational quality, they attract as their clientele the very elite of local culture.

THE BOARDS OF EDUCATION.

Lectureships maintained under legislative authority, and at public expense, by Boards of Education — as in New York City and State — for the propagation of useful information in the practical arts of domestic life, for the instruction of the public in the proper arts of sanitation, and of medical and surgical assistance in emergencies, and for the publication, exploitation and illustration of current scientific discoveries and inventions — these must be noted also.

UNIVERSITY SUMMER SESSIONS AND EXTENSION COURSES.

The summer sessions held each year under the auspices of our foremost Universities, and as a constituent section of their curriculum. Universities whose principal professors are retained as lecturers, and in which sessions all sorts of technical, sociologic, pedagogic, scientific and philosophic themes are presented luminously to thousands of secular school teachers, scholars, investigators and literati, must be noted also.

The University Extension Lecture Courses, covering almost every conceivable subject of human interest, whether to scholars or to students, and constantly increasing in number, in efficiency and in prophetic significance, — these must be noted also.

And next, there is the rapidly-multiplying host of Y.M.C.A. public lectureships, and of institutional church lectureships, covering technical instruction and inspiration in the trades, in the arts and in the industrial crafts. These, appealing principally to men, and in the out-of-business hours, and though admittedly but a by-aim of the ethical and religious propaganda of institutional Christianity, nevertheless afford first-class lectureships in the creative arts and in the commercial and the industrial utilities.

LECTURESHIPS PROVIDED BY CIVIC ENTERPRISE.

Next we note the multitudinous evening lectureships which, though appealing forcibly only to special classes of students, are yet also open to the general public, lectureships provided through civic enterprise and forecast, by manual training schools, institutes of technology and city high schools, such as the Mechanic Arts High School of Boston.

We note, also, the lectureships— restrictedly secular in the character of their instruction, and largely technical both in form and in spirit — conducted by the trade and guild schools and by schools of technique principally for their own clients, yet open to the public without charge. Such lectureships bring the enthusiasms as well as the incitements of education to thousands of citizens already mentally virile and alert.

THE SUMMER ASSEMBLIES.

The summer Assemblies — increasing at a most remarkable rate — with their free public platform, the freest in America, the most untrammeled, free for the announcement of the latest discoveries of fact in science, or in literature, or in art, free for the heralding of the grandest ideals in human thought, these Assemblies, with their schools and guilds and solidarities and incessant lectureships, these must be noted also.

The winter Assemblies, held for a single week in our largest churches, offering lectures of the highest order, three times each day, drawing talent from our greatest universities, seminaries and pulpits — these must be noted also.

WOMEN'S CLUBS

Literature and art lectureships conducted by women's clubs, by artists' clubs, and by schools of aesthetic culture, and furnishing both to their own intelligent and ambitious clientele and to the general public as well, the rudiments and the inspirations of artistic education, if not artistic life itself, — these also stand out clearly and nobly before the eye.

Between one and two thousand persons gain a livelihood upon the platform, while the number of those who devote only a part of their time to the platform cannot be fewer than three or four thousand. It seems hardly possible that this great business of to-day is but the outgrowth of a dream of yesterday. But so it is. Along in the first quarter of the century just closed, education, always a fad of the Americans, suddenly became a hobby. All sorts of societies were organized over night, societies for the diffusion of useful knowledge, mercantile associations, teachers' seminaries, literary institutes, book clubs, societies of education — every sort of society whose name sounded learned and educational. Some of them lasted only until the members could invent for them a baptismal name, and then quietly died. Few of them outlived the first ten years. Among this multitude was one insignificant little institution, established in November, 1826, as is recorded in the "American Journal of Education," by some forty or fifty farmers and mechanics of the little town of Millbury, Mass. There was nothing surprising in their forming an association. Organization was in the very air. Any town that wanted to be at all up to date had to organize something educational — two or three of them, if the town were large enough. So these Millbury farmers and mechanics formed themselves into "The Millbury Branch, No. 1, of the American Lyceum." "The American Lyceum," now an established fact and a household word in many a town, then only a dream — the dream of Josiah Holbrook, of Derby, Conn.

This historic character merits at least a paragraph. Josiah Holbrook was what an irreverent generation might call "a stone agent." A firm believer in the efficacy of natural science studies as a panacea for the cure of all sorts of educational ills, already, in 1826, he had spent several years traveling about Massachusetts and Connecticut, lecturing on geology and mineralogy, and urging every town to form its own little cabinets of specimens, and to study far more, not only these, but all the natural sciences. Wandering minstrels and traveling preachers there had been before, but never, we think, a peripatetic lecturer on the natural sciences. He was the first of this race; if not the first, at least the most genetic. Moreover, to him more than to anyone else do we owe the introduction of the natural sciences into our public school curriculums, as subjects for regular study. But his greatest title to remembrance is that he dreamed of an "American Lyceum," worked with all his strength to make that dream reality, and in truth laid the foundation for the great Lyceum system of to-day.

JOSIAH HOLBBOOK'S PLAN.

Now, what was this American Lyceum to be, as seen in Josiah Holbrook's dream? A means of popular education, of self-culture and of community instruction such as should make the wilderness of uncultivated mind blossom as the rose. Mr. Holbrook's plans, as outlined in Barnard's "Journal of Education," early in 1826, required that every town should have its own Lyceum, with library, collections of specimens in natural history, cabinets of mineralogical treasures, courses of lectures given by the members, the members themselves grouped in sections for the study of science, history and art. Delegates from the Town Lyceums were to form the County Lyceums, and from these, in turn, would be made up the State Lyceums, while the National American Lyceum was to be composed of delegates from all the State societies. Here is a scheme sufficiently large and far reaching, it would seem, to fill the ambition of the man who devised it, and whose life was devoted to its historic unfolding. Yet it was not. If Josiah Holbrook had lived to-day, probably he might have been tempted to organize an educational trust, or to corner the market in professors. As it was, he planned a World Lyceum, of which Chancellor Brougham, of England, should be president, and which should have fifty-two vice-presidents, men distinguished in science and in philanthropy, men chosen from every country in the world. And this, almost before the Millbury Lyceum, "Branch No. 1," was fully organized.

Brougham

The term "Brougham" has been used by every single American car manufacturer as well as a few foreign ones to designate a car model or trim package with richly appointed features. It refers to the elegant "Brougham" carriage popular in the 19th century. That carriage was originally built to the specifications of and named for Lord Henry Peter Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux, a British statesman who became Lord Chancellor of Great Britain. Brother Brougham was a member of Canongate Kilwinning Lodge 2 of Edinburgh Scotland.

-- Freemasons: Tales from the Craft, by Steven L. Harrison

However, we must not give Josiah Holbrook credit for an imagination too vivid and strenuous. The word "Lyceum" he borrowed from the spot where Aristotle used to lecture to the youth of Greece, while various details of his system were probably adapted from other sources. For instance, Franklin's Junto may have given him the idea of mutual instruction, and the Paris Lyceum, where Monsieur de la Harpe lectured daily from 1786 to 1794, is a possible source of his plan for instruction by series of lectures. The Paris Conservatory of Arts and Trades, founded in 1796, and the Mechanics' Institutes of England, which increased in number from one in 1823 to seven hundred in 1860, probably added somewhat to the form of Holbrook's grand scheme. But the system was his own. These other efforts at popular adult education were all comparatively small and insignificant; his was perhaps the most comprehensive system ever originated, without exception.

"The Millbury Branch, No. 1, of the American Lyceum'' was the first fruit of Holbrook's toil, lecturing, writing, distributing circulars, and travel. But Millbury happened to be only a little ahead of its neighbors. Twelve or fifteen nearby villages promptly followed its example, and early in 1827 Worcester County, Mass., could boast of having the first County Lyceum.

The Lyceum germ having now found a most fertile soil, it might have been safely left to grow and multiply without further solicitude on the part of Mr. Holbrook. But he never relaxed his efforts. Up and down and criss-cross he went, through Massachusetts and Connecticut, always talking Lyceum, and personally organizing hundreds of societies. In 1828 nearly a hundred branches of the "American Lyceum'' had been formed, and by the end of 1829 there were societies in nearly every State in the Union. Two years later their numbers were approaching a thousand, and in 1834, the high water mark was reached, at which time nearly three thousand town Lyceums were scattered throughout the United States, from Boston to Detroit and from Maine to Florida. The greatest interest was shown in New England and the South, where everyone who could stoop or talk was picking up stones for the Lyceum cabinet or working up lectures for the benefit of his fellow-members.