by https://newidealsineducation.blogspot.c ... dmond.html

Saturday, September 8, 2018

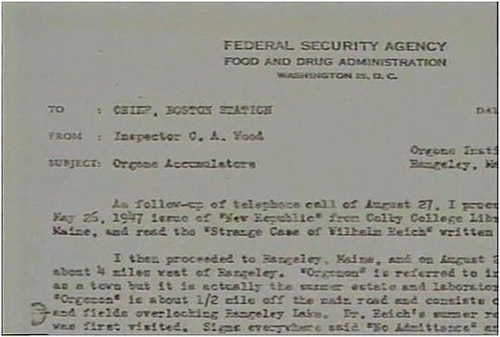

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

The Beginning of New Ideals and Edmond Holmes

There were three key male figures behind New Ideals in Education, who helped create the first conference and supported the organisation and later conferences.

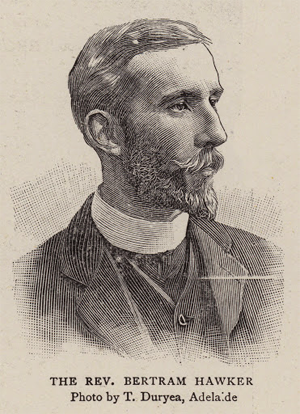

As already mentioned, in the last blog, there was Rev Bertram Hawker, who went on to work with Save the Children, the international student union movement and helped Kurt Hahn to establish (1934) Gordonstoun School. Edmond Holmes and Earl Lytton were the other two.

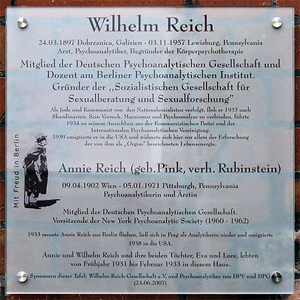

Edmond Holmes

Edmond Holmes had been Chief Inspector of Schools and like Bertram Hawker, was interested in Montessori, visiting her in Rome (late 1910) whilst using an interpreter, and writing a report for the Government (published 1912). Though he had originally been inspired before 1911 by a different woman, the headteacher of Sompting School, Harriet Finlay Johnson. This lead to him promoting her and her school to local authorities and assisting her engagement with other teachers and educationalists.

He was determined to seek out innovative practice, to observe it and share it with others, this was how to define and bring about the modern school. He argued that all inspectors, who knew of innovatory methods should do the same, and that there should be a Clearing House for such experiments. This would later be set-up for the world as the International Bureau of Education, now part of UNESCO, partly from people involved in the New Education (International) Fellowship and New Ideals. Though the history, as usual, was dominated by the Fellowship's founder, Beatrice Ensor, who wrote out the influence of New Ideals, though this history was contested publicly at the time.

In New Ideals of Education Holmes initiated 'experiment days' in which teachers shared their successful innovative methods.

“Ladies and Gentlemen – Experiment Days is for me the fulfilment of a long cherished dream. For five years I was what is called Chief Inspector of Elementary Schools in England, in which capacity I visited every district in the country and got to know every inspector. My colleagues showed me sport, in the form of interesting schools; and it did not take me long to discover that in many of our elementary schools experimental work of an original type was being done, and remarkable results – not of the conventional order – were being produced. But what distressed me… Apart from HM Inspectors, the local inspector, or director, a few neighbouring teachers, and the parents of the children, no-one knew what was being done… I felt then what an urgent need there was for the establishment of what I may call a clearing-house for educational ideas and experiences…” Edmond Holmes, August 18th 1917, New Ideals Conference, Bedford College, p85

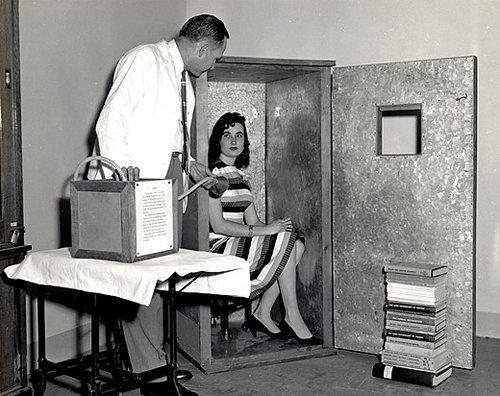

Sompting children on nature walk interview each other as flowers.

He wrote What Is and What Might Be (1911), which was based on his views of Sompting School being the model school of the future, what all schools should be like. His hero was Harriet Finlay Johnson, who had started using nature in all her lessons, to teach maths, English, history... and then realised that drama was the key creative element in her teaching method. She later wrote one of the first books on the use of drama as a teaching method, The dramatic Method of Teaching, (review in New Statesmen 1911).

Harriet Finlay Johnson was invited as a key speaker at the Montessori Conference in East Runton. Edmond Holmes gave several presentations about her work.

Holmes was very influential in effecting the views of powerful people, he visited Sir William Mather, the industrialist, who subsequently became an enthusiastic member of the New Ideals community, funding such things as 6,000 free pamphlets for teachers describing five case models of successful practice in 'liberating the child'. Published in 1917 they were distributed free to teachers requesting them, and were all distributed by 1918.

More regional and national conferences followed the one at Elsinore, including a Commonwealth Conference organized by Nunn in London to further his plan for an Institute of Education to rival Teachers College, Columbia University and the Institut J. J. Rousseau.114 In France, a new group emerged to take over Pour l’ère Nouvelle. Included in this group was the Marxist psychologist Henri Wallon, founder in 1921 of Le Groupe Français d’Education Nouvelle, who held the chair of Education and Psychology of Children at Collège de France and the Communist educator Célestin Freinet, who had been much impressed by meeting Ferrière at Montreux115.

Wallon spoke at the next international conference held at Nice in 1932. The chair of the conference was the physicist Paul Langevin, who was an honorary president of Groupe Français d’Education Nouvelle. The attendance was lower than at the previous conference but there were significant numbers from England, the USA, Germany and France. Delegates attended the conference from fifty-three different countries. Around 27% of those who spoke could be said to be from the academy.116 The conference theme was “Education in a changing society”. Harold Rugg wrote, after the conference, that it marked a turning point in the history of the NEF. A reconstructionist, Rugg was opposed to the position held by the NEF throughout the 1920s. His claim that the very theme of the conference “was indicative of a change in the vision and drive of the fellowship” was more in the nature of a wish than a reality, and he added that his was a “personal interpretation” as the conference would not adopt a “clear pronouncement”.117 This was a reference to the new principles that had already appeared in The New Era and which were discussed at the conference. These shifted the emphasis from the individual’s to social needs. Hemmings interpreted this “retreat from freedom”, as he termed it, as a response to hopes dashed by the coming to power of Stalin in the USSR on the one hand and the “infiltration” and “virtual takeover” of the NEF by a number of professors on the other. He singled out Fred Clarke, Nunn’s successor as Director of the Institute of Education in London, as initiating the turn from educational radicalism.118 This judgement individualizes what was much more a collective reorientation. It also assumes, unjustifiably, that disciplinary fields have absolute autonomy. Boyd wrote of the 1930s that, “with the growth of fascism there was a shift of interest from child to society among new educators, and gradually the concern about methods dwindled”.119

-- A new education for a new era: the contribution of the conferences of the New Education[al] Fellowship to the disciplinary field of education 1921–1938, by Kevin J. Brehony

Other people included Sir Robert Morant, Holmes' previous boss, Permanent Secretary to the Department for Education, who attended and chaired presentations at several New Ideals Conferences.

Holmes is also recognised as influencing many people in supporting the work and values of Maria Montessori.

He was on the organising committee of New Ideals, attended all the conferences that he could, and spoke at numerous events, including on comparing the educations systems of Germany and England, linking their outcomes with the war.

“The pressure of autocratic authority tends to externalise life. The verdict of authority – external, visible, embodied authority – takes the place of the verdict of experience, of life, of Nature. An officer’s or a teacher’s estimate of worth is accepted as final and decisive. An examiner’s certificate determines a man’s ‘station and degree’. Class lists, orders of merit, prizes, medals, titles, grades, and the like interpose themselves between the soul and the ultimate realities of existence. Under such a regime the sense of intrinsic reality is gradually lost. What is reported to be is a man’s chief concern, not what he really is.” Mr Edmond Holmes, New Ideals in Education Conference 1915, 'Ideals of Life and Education – German and English', P14.

Like many other activists in the movement Holmes was interested in religions from the East, Buddhism, pantheism, mysticism and theosophy, in the free development of the spirit or soul.

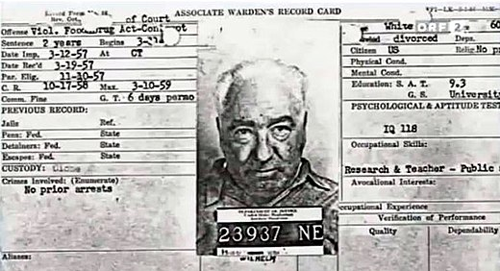

His publications include (as listed in Wikipedia):

• Poems (1876)

• Poems (1879)

• A Confession of Faith. By an Unorthodox Believer (1895)

• The Silence of Love (1901)

• Walt Whitman's Poetry: A Study & A Selection (1902)

• The Triumph of Love (1903)

• The Creed of Christ (1905)

• The Creed of Buddha (1908)

• What Is and What Might Be (1911)

• The Creed of My Heart (1912)

• In Defence of What Might Be (1914)

• Sonnets to the Universe (1918)

• Sonnets and Poems

• Experience of Reality. A Study of Mysticism (1928)

• Philosophy Without Metaphysics (1930)

• The Headquarters of Reality. A Challenge to Western Thought (1933).

The Creed of Buddha, by Edmond Holmes

A brilliant set of essays were published by Personalised Education Now in their journal Spr/Sum 2010-11 Issue No 14, ISSN1756-803X, Special Issue celebrating Edmond Holmes.

**********************

The Beginning of New Ideals & Bertram Hawker

by http://newidealsineducation.blogspot.co ... rtram.html

August 21, 2018

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

The New Ideals in Education community started in 1914 as the first national conference of the Montessori Society held at East Runton, Norfolk, just along the coast from Cromer. Dr Maria Montessori sent them a supporting telegram, “I associate myself cordially with the Conference in favour of the liberation of the child. Grateful for the recognition of my work.” read out by the Chairman of the opening presentation, Mr B.V. Melville. 50 of the delegates were members of the Society, their names, as for later years, printed in italics in the participant list published in each conference report.

Child in Montessori School run by Bertram Hawker at E. Runton.

There were 250 delegates, many camping, and the conference was held in the grounds, buildings and barn of Rev Bertram Hawker's house, Runton Old Hall. There were the children and teachers from Hawker's Montessori School exhibiting the method. It had been created with support from the local elementary school teachers and local Board in November 1912. This was the first Montessori School in England, and reflected Hawker's enthusiasm for the method and ideas. Photographs of the school illustrated the first Montessori Handbook published in England. Hawker had given talks on Montessori around the country.

Picture from Dr Montessori's Own Handbook 1914

Hawker had been impressed by visiting Montessori's Casa dei Bambini in Rome in 1911, he funded Lillian de Lissa travelling in Europe to research methods of schooling and to be trained by Montessori. She also wrote a report for South Australian government, 'Education in certain European countries' (1915). He also helped fund and support the creation of the Kindergarten Union of South Australia, chairing their foundation meeting, as a result of being impressed by the work he saw at a special school for young children of families living at Woolloomooloo. It is interesting that the Union, founded and managed by women had to later fight the male dominated power structures of the University to maintain its autonomy over the training of Kindergarten teachers. Lillian de Lissa was opening speaker at the Montessori Conference in 1914.

Hawker earlier had worked in East London, was inspired by the settlement communities, and their work with poor children. He attended nearly all the New Ideals in Education Conferences, only speaking to replace a key speaker, like Edmond Holmes. Holmes had been chief inspector of schools in England. He saw the need for models of excellent practice to be supported, celebrated and shared. This community was inspired by the method and philosophy of Dr Maria Montessori, who believed in observing learning and teaching and basing methods on science. The founders, men and women, were practitioners and others, who saw innovative methods in practice. They would go on to create a growing community founded on innovation, observation and sharing. The common value to all this, as proposed by Percy Nunn, was 'liberating the child in the school'.

The Rev. Bertram Hawker

Despite the change in name before the next conference in 1915, and the acceptance of the value statement 'liberating the child', the conferences continued to discuss and share Montessori examples of practice; the New Ideals organising committee and delegates included members of the Montessori Society; and in the published delegates list members of the Montessori Society were continued to be highlighted in italics. This despite the anger of Dr Maria Montessori, who did not want to lose control of her methods and materials, and who ensured the new Montessori Society in England would protect her property rights.

This history shows there was no animosity towards her ideas, though healthy criticism and promotion of the idea of the ongoing development of methods, and an acceptance that they should contribute to the future of the English school. All the conferences and their reports start with a brief history of the community, always referencing the Montessori Conference at East Runton, as its birth. This does seem to contradict the history as retold by people who are from the modern international Montessori community.

One interesting thought about the relationship with Montessori was the importance of innovation and the practitioner, the scientist, the professor, was not to be elevated above the teacher. Each was to be judged by witnesses and reports of their practice.

**********************

The Most Remarkable Teacher You’ve Never Heard Of – Harriet Finlay Johnson

by Alan Parr

January 5, 2018

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

I recently wrote about how silly it is for critics to claim that “The Blob” introduced innovative teaching and learning methods and perverted schools in the 1960s. In fact such ideas can be traced back to a century earlier, and perhaps the most remarkable school of all could be found in a Sussex village between 1897 and 1910. Under Harriet Finlay Johnson Sompting School became famous across England and as far away as the USA and Japan.

One of the better times to be a teacher in an English elementary school was the first decade of the twentieth century. No longer did a single teacher have to cater for dozens of children in several different classes in one large room. Public attitudes had changed; large-scale absenteeism and illiteracy had been replaced by ever-increasing numbers of pupils voluntarily staying on, studying a curriculum that covered work we’d now see as largely of secondary school levels. Government and local authorities now were making it clear teachers and schools had the autonomy to teach as they themselves saw best and to take into account the needs of the school and the child.

Furthermore, the inspector’s role was completely different to before. No longer might the annual inspection humiliate children and teachers alike; he (I haven’t yet come across a female HMI, though the local authorities were now appointing women to inspect particular subjects) could now act as the friend and supporter of the school, recognising good practice and disseminating it to others.

So the climate was more friendly to experimentation and innovation than ever before. And something quite remarkable emerged in a Sussex village called Sompting. There were thousands of schools in such villages – I’ve studied half a dozen of them. A population of a few hundred, with between 100 and 150 children, many of them walking several miles a day to get to a school with just a couple of teachers. Between them, the church and the school were the focus of a way of life that was beginning to disappear as a more mechanised and urban lifestyle developed.

Harriet Finlay Johnson came to Sompting as the Head of the school in 1897. Over the next dozen years there were three features of her work that contributed to the school, and herself, becoming known across the country and far beyond. The first was a belief that children needed to be happy – “Childhood should be our happiest time” and “We do our best when we are happy.” Part of her philosophy was a strong belief that children had a personal contribution to make to the learning of themselves and their classmates – “Children have a wonderful faculty for teaching other children and learning from them.” This became the culture, not just in the main school but in the infant section as well.

Creating a positive approach to learning was more important to her “than the mere ability to spell a large number of extraordinary words, to work a certain number of sums on set rules, or to be able to read whole pages of printed matter without being able to comprehend a single idea, or to originate any new train of thought”. She went much further than this, and – in words that still seem pretty revolutionary more than a century later – worked towards the teacher being an equal partner with the child in the decision-making process “… the teacher, being a companion to and fellow worker with the pupils, … shared in the citizen’s right of holding an opinion, being heard, therefore, not as “absolute monarch,” but on the same grounds as the children themselves”.

The second reason for her becoming widely known was the emphasis she placed upon making the study of nature a main focus of the curriculum. Not as a sedentary classroom subject, but with frequent rambles and nature walks, and gardening. She was able to use the interest in nature as a basis for lessons across almost the whole curriculum – in singing, reading, writing, arithmetic, drawing, composition, grammar, geography. Children without gardens of their own would adopt neglected areas in the village, and by 1903 her work in Nature Study had brought her recognition and she was invited to become a member of the Education Advisory Committee for West Sussex. In the following year she spoke on “The Teaching Of Nature Study in Public Elementary Schools” to managers and teachers.

The third aspect perhaps brought her most recognition of all. By her own account, it developed almost by accident as the result of a remark by a pupil. She’d always been keen to make use of role play, whether in geography, arithmetic, or most other subjects, and one day in a history lesson, a boy asked “Couldn’t we play Ivanhoe?” According to her, the effect was literally dramatic, eventually culminating in her book “The Dramatic Method of Teaching”.

Following the Ivanhoe suggestion the children threw themselves into the book ever more deeply. They needed to decide which episodes to dramatise, they researched costumes, dialogue, and the selection of props. With some satisfaction Harriet Finlay Johnson said “we had put the text book in its proper place, not as the principal means, but merely as a reference, and for assistance“.

Before long the “dramatic method” became the central feature of her school’s curriculum, so effectively that many children chose the works of Shakespeare as their leaving present. Indeed, in 1908 the young men of the village (many of them, of course, Harriet Finlay Johnson’s ex-pupils) asked her to help them form an evening drama club. Their version of Julius Caesar was performed at Worthing and received local and national praise.

I can best put her work into perspective by mentioning another school I’ve studied in some depth. I recently gave a talk to the local history group at Ayhno. The similarities could hardly be greater – Sompting and Aynho were both rural villages with about 120 children in the school. Both had heads with previous experience, who were both supported by close family members – Harriet Finlay Johnson had her sister to teach the infants, Allen R Hill at Aynho had his daughter Edith. Their careers were exactly contemporaneous – Harriet Finlay Johnson was at Sompting from 1897 to 1910, Allen Hill at Aynho from 1897 to at least 1908.

Yet their achievements and the atmosphere of their schools were completely different. On one occasion at Sompting an emergency meant there were no adults in the school. When Harriet Finlay Johnson finally arrived halfway through the session she found everyone hard at work. The oldest children had organised a programme, selected teachers and topics, and implemented lessons across both the main school and the infants as well.

But even after ten years at Aynho Allen R Hill had a school where commitment and discipline were a daily challenge. Not a week goes by without his recording bad behaviour and the use of physical punishment; on occasion he even calls the police. And Sompting pupils weren’t naturally angelic – they didn’t come out well in inspection reports before Harriet arrived, and when she left she was replaced by a strict disciplinarian who had to be dismissed when his severe beatings of pupils caused uproar.

Allen Hill accepted a ferocious workload and worked with total commitment, but even in Aynho he’s forgotten, while in Sompting the village community centre bears Harriet Finlay Johnson’s name and a blue plaque commemorates her life.

For several years visitors flocked to Sompting School. Four members of HMI came in a single year; the Chief Inspector made visit after visit. Cumberland – just about as far away from Sussex as a county can be – sent its inspector. Colleges sent tutors and their students, and reporters came from the Daily Mirror and Daily Mail.

She wrote a book called “The Dramatic Method of Teaching”, which received an enthusiastic review in The Spectator. Both the full text of the book and the review are easily available online:

https://archive.org/details/dramaticmethodof00finlrich

http://archive.spectator.co.uk/article/ ... f-teaching

Interviewed many years later, ex-pupils remembered her ability to put her ideas into action and carry children with her. She gave children responsibility, and expected them to think for themselves. (“I began to see how it might be possible to throw more of the actual lessons, including their preparation and arrangement, onto the scholars themselves. Besides, in my opinion, more than half the benefit of the lesson lies in the act of preparing it, in hunting its materials out of hidden sources and collecting them into shape”).

This wasn’t necessarily popular – at a school entertainment evening a lady visitor said “This is all very fine, but if this sort of thing goes on, where are we going to find our servants?”

The Vicar had a similar complaint. In the same year (1907) he grumbled that too many of the village’s 13-yearolds were staying on at school rather than going out to work. He accused them of being “unenterprising”, but in fact their willingness to learn, commitment, and all-round knowledge meant Sompting pupils were highly sought-after by potential employers.

By the end of the decade important people in the education world were saying that Sompting was not just a wonderfully effective school, but the best school in the land. If, like me, you’ve never heard of Harriet Finlay Johnson, you may be wondering two things. Exactly how did she become so well known that her work influenced thinking as far away as Japan and the USA? And why did her classroom career come to an end in 1910, when she was still only in her thirties and had years more to offer?

I guess I’d better write part (ii) and tell you what happened.