by Wikipedia

Accessed: 9/28/22

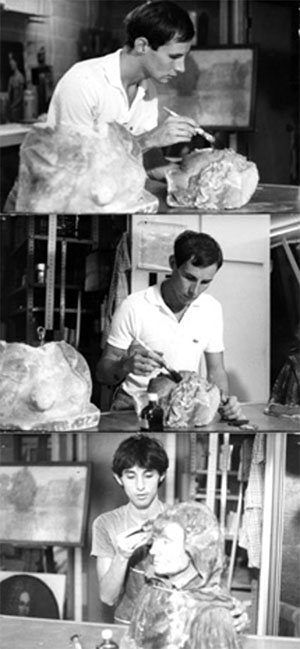

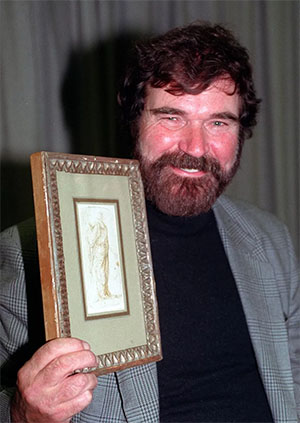

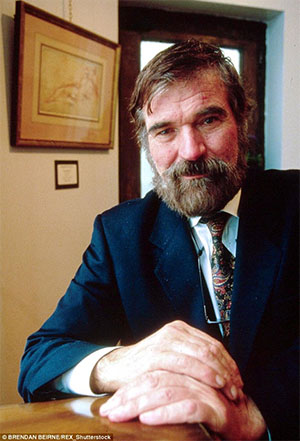

Artist Eric Hebborn with his original drawing in the manner of 15th century artist, Fra Bartolomeo. Photo by Tim Ockenden - PA Images/PA Images via Getty Images.

Eric Hebborn

Born: 20 March 1934, South Kensington, London, England

Died: 11 January 1996 (aged 61), Rome, Italy

Education: Royal Academy

Known for: Painting, Sculpture, Drawing, Art forgery

Movement: Realism

Eric Hebborn (20 March 1934 – 11 January 1996) was an English painter, draughtsman, art forger and later an author.

Early life

Eric Hebborn was born in South Kensington, London in 1934.[1] His mother was born in Brighton and his father in Oxford. According to his autobiography, his mother beat him constantly as a child. At the age of eight, he states that he set fire to his school and was sent to Longmoor reformatory in Harold Wood, although his sister Rosemary disputes this.[citation needed] Teachers encouraged his painting talent and he became connected to the Maldon Art Club, where he first exhibited at the age of 15.

Hebborn attended Chelmsford Art School and Walthamstow Art School before attending the Royal Academy. He flourished at the academy, winning the Hacker Portrait prize and the Silver Award, and the British Prix de Rome in Engraving, a two-year scholarship to the British School at Rome in 1959.[2] There he became part of the international art scene, establishing acquaintances with many artists and art historians, including Soviet spy Sir Anthony Blunt in 1960, who told Hebborn that a couple of his drawings looked like Poussins. This sowed the seeds of his forgery career.

Hebborn returned to London, where he was hired by art restorer George Aczel. During his employ he was instructed not only to restore paintings, but to alter and improve them. Aczel graduated him from restoring existing paintings to "restoring" paintings on entirely blank canvases so that they could be sold for more money. A falling out over Hebborn's knowledge of painting and restoration destroyed the relationship between him and Aczel.

Hebborn and his lover Graham David Smith[3] also frequented a junk and antique shop near Leicester Square, where Hebborn befriended one of the owners, Marie Gray. In organizing the prints catalogued in the shop, Hebborn began to learn more about paper, and its history and uses in art. It was on some of these blank old pieces of paper that Hebborn made his first forgeries.

His first true forgeries were pencil drawings after Augustus John, based on a drawing of a child by Andrea Schiavone. Smith states that several of these were sold to their landlord Mr Davis, several to Bond Street galleries and two or three through Christie's sale rooms.[3]

Eventually Hebborn decided to settle in Italy with Smith. They founded a private gallery there.

Life as a forger

When contemporary critics did not seem to appreciate his own paintings, Hebborn began to copy the style of old masters such as: Corot, Castiglione, Mantegna, Van Dyck, Poussin, Ghisi, Tiepolo, Rubens, Jan Breughel and Piranesi. Art historians such as Sir John Pope Hennessy declared his paintings to be both authentic and stylistically brilliant and his paintings were sold for tens of thousands of pounds through art auction houses, including Christie's and Sotheby's.[4] According to Hebborn himself, he had sold thousands of fake paintings, drawings and sculptures. Most of the drawings Hebborn created were his own work, made to resemble the style of historical artists—and not slightly altered or combined copies of older work.

In 1978 a curator at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC, Konrad Oberhuber, was examining a pair of drawings he had purchased for the museum from Colnaghi, an established and reputable old-master dealer in London: one by Savelli Sperandio and the other by Francesco del Cossa. Oberhuber noticed that two drawings had been executed on the same kind of paper.

Oberhuber was taken aback by the similarities of the paper used in the two pieces and decided to alert his colleagues in the art world. Upon finding another fake "Cossa" at the Morgan Library, this one having passed through the hands of at least three experts, Oberhuber contacted Colnaghi, the source of all three fakes. Colnaghi, in turn, informed the worried curators that all three had been acquired from Hebborn,[5] although Hebborn was not publicly named.[4]

Colnaghi waited a full eighteen months before revealing the deception to the media, and even then never mentioned Hebborn's name, for fear of a libel suit. Alice Beckett states that she was told '...no one talks about him...The trouble is he's too good'.[6] Thus Hebborn continued to create his forgeries, changing his style slightly to avoid any further unmasking, and manufactured at least 500 more drawings between 1978 and 1988.[2] The profit made from his forgeries is estimated to be more than 30 million dollars.[7]

Confession, criticism and death

In 1984 Hebborn admitted to a number of forgeries -– and feeling as though he had done nothing wrong, he used the press generated by his confession to denigrate the art world.

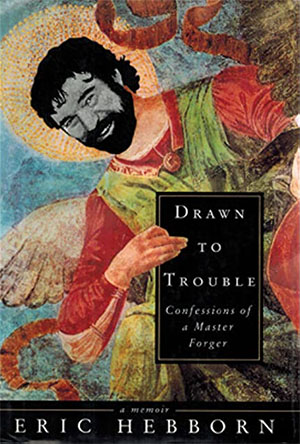

In his autobiography Drawn to Trouble (1991), Hebborn continued his assault on the art world, critics and art dealers. He spoke openly about his ability to deceive supposed art experts who (for the most part) were all too eager to play along with the ruse for the sake of profit. Hebborn also claimed that some of the works that had been proven genuine were actually his fakes. During this period, Hebborn went on record to state that Sir Anthony Blunt and he had never been lovers.

On one page he offers a side-by-side comparison of his forgeries of Henri Leroy by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, and the authentic drawing, challenging "art experts" to tell them apart.[5]

On 8 January 1996, shortly after the publication of the Italian edition of his book The Art Forger's Handbook, Eric Hebborn was found lying in a street in Rome, having suffered massive head trauma possibly delivered by a blunt instrument. He died in hospital on 11 January 1996.[5]

The provenance of many artworks attributed to Hebborn, including some which are alleged to hang in renowned collections, continues to be debated. Both the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, California and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City deny that they feature any Hebborn forgeries, although this was disputed by Hebborn himself.[4]

Legacy

A documentary film Eric Hebborn: Portrait of a Master Forger, featuring an extended interview with Hebborn at his home in Italy, was produced for the BBC's Omnibus strand and broadcast in 1991.

The 2014 novel In the Shadow of an Old Master is based on the mystery surrounding Eric Hebborn's death and its aftermath.[8]

In October 2014 it was announced that 236 drawings were to be sold, in individual lots, ranging in price from £100 to £500 each, by auctioneers Webbs of Wilton in Wiltshire. On 23 October 2014 the drawings went on to sell for over £50,000, with one sanguine drawing, after a design by Michelangelo, selling for £2,200, more than 18 times its expected price; Hebborn's modern drawing manual, The Language of Line, complete with pencil corrections and edits, sold for more than £3,000.[9] Although the identity of the successful purchaser of The Language of Line remains unknown, and no further copies are thought to have been in existence, Hebborn's former agent Brian Balfour-Oatts allowed The Guardian to have sight of the manuscript, which had been sent to him by a friend of the artist. Details of the previously unpublished text were published by the newspaper in August 2015.[10]

Hebborn's books

• Drawn to Trouble, Mainstream, 1991 ISBN 1-85158-369-6

• The Art Forger's Handbook, Overlook, 1997 (posthumous) ISBN 1-58567-626-8

• Confessions of a Master Forger, Cassell, 1997 (posthumous reprint of Drawn to Trouble, with epilogue by Brian Balfour-Oatts) ISBN 0-304-35023-0

See also

• Han van Meegeren

• Tom Keating

References

1. (in French)Delarge Dictionnaire

2. Death of a Forger Archived 2 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine by Denis Dutton University of Canterbury

3. Celebration: The Autobiography of Graham David Smith, Graham David Smith, Mainstream, 1996 ISBN 1-85158-843-4

4. CNN.com The prolific forger whose fake 'Old Masters' fooled the art world, 24 October 2019

5. False Impressions: The Hunt for Big-Time Art Fakes, Thomas Hoving, Simon & Schuster, 1996 ISBN 0-684-83148-1

6. "Fakes: forgery and the art world", Alice Beckett, RCB, 1995

7. "Authentication in Art Unmasked Forgers".

8. Blake, P. J. (2014). In the Shadow of an Old Master. London: Matador. ISBN 9781783065080

9. "Art forger Eric Hebborn collection sells for thousands". BBC News. 23 October 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

10. Alberge, Dalya (24 August 2015). "Great art forger continues to ridicule experts from beyond the grave". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

External links

• Artfakes

• Eric Hebborn – Portrait of a Master Forger on YouTube

**************************

Eric Hebborn & Graham David Smith

by Elisa Rolle

March 20, 2015

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Eric Hebborn (20 March 1934 – 11 January 1996) was a British painter and art forger and later an author.

Eric Hebborn was born in the London suburb of South Kensingtonin 1934. His mother was born in Brighton and his father in Oxford. According to his autobiography, his mother beat him constantly as a child. At the age of eight, he states that he set fire to his school and was sent to Longmoor reformatory in Harold Wood, although his sister Rosemary disputes this. Teachers encouraged his painting talent and he became connected to the Maldon Art Club, where he first exhibited at the age of 15.

Hebborn attended Chelmsford Art School and Walthamstow Art School before attending the Royal Academy. He flourished at the Academy, winning the Hacker Portrait prize and the Silver Award, and the British Prix de Rome in Engraving, a two-year scholarship to the British School at Rome in 1959. There he became part of the international art scene and formed acquaintances with many artists and art historians, including the British spy, Sir Anthony Blunt in 1960, who told Hebborn that a couple of his drawings looked like Poussins. This sowed the seeds of his forgery career.

Hebborn returned to London where he was hired by art restorer George Aczel. During his employ he was instructed not only to restore paintings, but to alter them and improve them. George Aczel graduated him from restoring existing paintings to "restoring" paintings on entirely blank canvases so that they could be sold for more money. A falling out over Eric's knowledge of painting and restoration destroyed the relationship between Aczel and Hebborn.

Eric and his lover Graham David Smith also frequented a junk and antique shop near Leicester Square, where Eric befriended one of the owners, Marie Gray. In organizing the prints catalogued in the shop Eric began to understand more about paper, and its history and uses in art. It was on some of these blank, but old, pieces of paper that Eric made his first forgeries.

His first true forgeries were pencil drawings after Augustus John and were based on a drawing of a child by Andrea Schiavone. Graham Smith states that several of these were sold to their landlord Mr Davis, several to Bond Street galleries and two or three through Christie's sale rooms.

Eventually Hebborn decided to settle in Italy with Graham, and they founded a private gallery there.

When contemporary critics did not seem to appreciate his own paintings, Hebborn began to copy the style of old masters such as: Corot, Castiglione, Mantegna, Van Dyck, Poussin, Ghisi, Tiepolo, Rubens, Jan Breughel and Piranesi. Art historians such as Sir John Pope Hennessy declared his paintings to be both authentic and stylistically brilliant and his paintings were sold for tens of thousands of pounds through art auction houses, including Christie's. According to Hebborn himself, he had sold thousands of fake paintings, drawings and sculptures. Most of the drawings Hebborn created were his own work, made to resemble the style of historical artists—and not slightly altered or combined copies of older work.

In 1978 a curator at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC, Konrad Oberhuber, was examining a pair of drawings he had purchased for the museum from Colnaghi an established and reputable old-master dealer in London, one by Savelli Sperandio and the other by Francesco del Cossa. Oberhuber noticed that two drawings had been executed on the same kind of paper.

Oberhuber was taken aback by the similarities of the paper used in the two pieces and decided to alert his colleagues in the art world. Upon finding another fake "Cossa" at the Morgan Library, this one having passed through the hands of at least three experts, Oberhuber contacted Colnaghi, the source of all three fakes. Colnaghi, in turn, informed the worried curators that all three had been acquired from Hebborn.

Colnaghi waited a full eighteen months before revealing the deception to the media, and, even then never mentioned Hebborn's name, for fear of a libel suit. Alice Beckett states that she was told '...no one talks about him...The trouble is he's too good'. Thus Hebborn continued to create his forgeries, changing his style slightly to avoid any further unmasking, and manufactured at least 500 more drawings between 1978 and 1988.

In 1984 Hebborn confessed to the forgeries —and feeling as though he had done nothing wrong, he used the press generated by his confession to denigrate the art world.

In his autobiography Drawn to Trouble (1991), Hebborn continued his assault on the art world, critics and art dealers. He boasted of how easily he had fooled supposed art experts and how eager the art dealers were to declare his works authentic to maximize their profits. Hebborn also claimed that some of the works that had been proven genuine were actually his fakes and that Sir Anthony Blunt had not been his lover, as stated in some articles. On one page he offers a side-by-side comparison of his forgeries of Henri Leroy by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, and the authentic drawing, challenging "art experts" to tell them apart.

On 8 January 1996, shortly after the publication of the Italian edition of his book The Art Forger's Handbook, Eric Hebborn was found lying in a street in Rome, his skull crushed with a blunt instrument. He died in hospital on 11 January 1996.

The provenance of many paintings connected to Hebborn, some of which hang in renowned collections, continues to be debated.

A documentary film Eric Hebborn: Portrait Of A Master Forger, featuring an extended interview with Hebborn at his home in Italy, was produced for the BBC Omnibus strand and broadcast in 1991.

Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eric_Hebborn

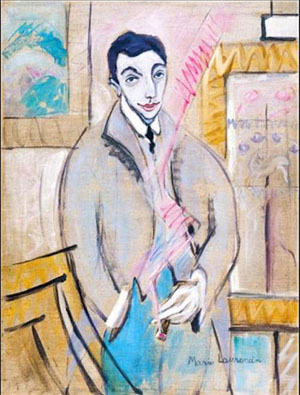

Graham David Smith (born 1937) is an artist and writer currently living in London. He has also worked in the USA under the name Paul Cline.

Born in the East End, Smith attended Walthamstow art school where in 1956 he met and became the lover of Eric Hebborn, who was to become a notorious art forger. Smith moved on to the Royal College of Art and Hebborn to the Royal Academy, but the couple stayed together for the next 13 years.

Upon Hebborn's return from a two-year stay in Italy after winning the Academy's Prix-de-Rome, the couple lived together in the run-down Cumberland Hotel in Highbury. They set up business buying and selling art, and spent many hours scouring junk shops for bargains. They befriended Marie Gray, who owned a shop near Leicester Square, and it was at her suggestion and from her stock that they used blank sheets of period paper upon which Hebborn could create original drawings, while Smith 'antiqued' them.

In 1963 they moved to Italy and opened a gallery, which attracted the attention of several of the art cognoscenti of the day. Notable amongst them was Sir Anthony Blunt, who often stayed with the couple when visiting Rome.

Smith and Hebborn grew apart and in 1969 Smith returned to London. He moved into fabric and wallpaper design, creating stylised designs of trees, flowers, birds and animals for Jean Muir and Osborn & Little, amongst others.

In the late 1970s Smith relocated with his lover John Elliker to California, and again changed artistic direction, now working in book illustration under the name Paul Cline.

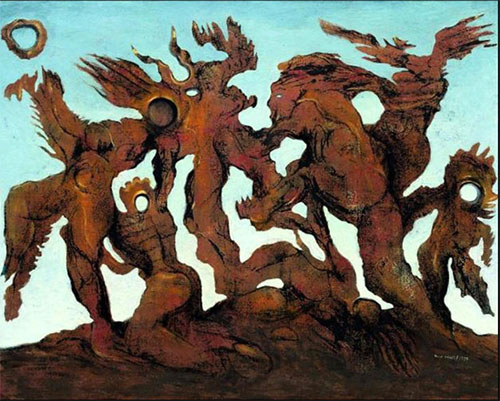

After Elliker died in 1987, Smith began to create a series of erotic drawings influenced by the medieval Dance of Death, and the resurrection of the genre by the Mexican artist José Guadalupe Posada. These reflected his horror at the impact of AIDS on the homosexual community. Geraldine Norman, in her article in the Independent newspaper refers to them as 'terrifying' and states that they use 'a highly finished academic style, reminiscent of the fine drawing taught by 19th century French academies'. They were exhibited in the Rita Dean gallery in San Diego.

At this time Smith also lived a parallel life on the fringe of the hustler community in Los Angeles. He became friendly with Rick Castro and memorably appeared as Ambrose Sapperstein in his 1996 movie Hustler White.

Smith's autobiography was published in 1996, which, he says, he wrote partly to refute some of the claims of Hebborn's own autobiographical work.

In 1997 Smith returned to London where he now lives. He continues to write, mainly poetry, and to create further tableaux drawings on death and homo-erotic themes.

Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Graham_David_Smith

Further Readings:

Drawn to Trouble: Confessions of a Master Forger: A Memoir by Eric Hebborn

Hardcover: 380 pages

Publisher: Random House (April 27, 1993)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0679420843

ISBN-13: 978-0679420842

Amazon: Drawn to Trouble: Confessions of a Master Forger: A Memoir

A premier art forger describes his rags-to-riches journey into the dark side of the art world, detailing the shady intrigues of the world's great museums and auction houses and offering a lesson in forgery techniques. 15,000 first printing.

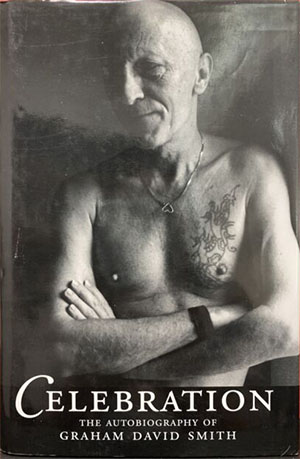

Celebration: The Autobiography of Graham David Smith by Graham David Smith

Hardcover: 256 pages

Publisher: Mainstream Publishing (February 1998)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 1851588434

ISBN-13: 978-1851588435

Amazon: Celebration: The Autobiography of Graham David Smith

Graham David Smith has lived a life overflowing with incident and adventure. This autobiography is a memoir of an eventful and picaresque journey through five decades and across two continents. It shows us the man in the circumstances and the places that formed him: in the slums of London shortly before the Blitz, where he was raped at the age of six; at the Royal College of Art, watching David Hockney perform in drag; submerging himself in the "dolce vita" of Rome in the 1960s with his lover, the celebrated art forger Eric Hebborn, where he became a hustler and first explored the world of S&M. Back in London in the 1970s he embarked on an endless round of drugs, parties and sex, somehow finding the time to paint and design fabrics. By the 1980s he was in Laguna Beach, California, a pleasure-ground of cocaine, sex and sun, the days filled with surfing, party boys and drug deals gone wrong - a hedonistic heaven before AIDS took hold. Smith is revealed as a friend and confidant of Derek Jacobi, Sir Anthony Blunt, Christine Keeler, Fellini, Pasolini, David Bowie and Lindsay Kemp. The autobiograhy celebrates what it means to be alive.

******************************

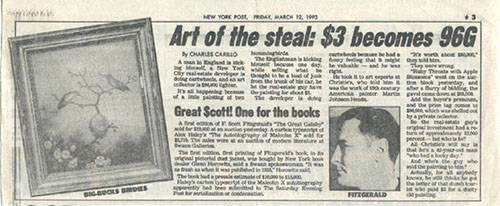

Drawings and paintings by the 'greatest forger of the 20th Century' are to be auctioned nearly 20 years after his brutal murder

by Amanda Williams

Daily Mail

PUBLISHED: 07:42 EDT, 1 June 2015 | UPDATED: 08:54 EDT, 1 June 2015

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

• Eric Hebborn duped art dealers and galleries world-wide with paintings

• Created works in style of Michelangelo, Rembrandt, and Claude

• His work was so convincing that dealers sold them on as genuine originals

• Hebborn was murdered in Italy in 1996 and his killing remains unsolved

His forgeries were so expertly executed that they duped hundreds of art critics the world over - including top auction house Christie's.

But now the artwork of master conman Eric Hebborn, whose forgeries included copies of Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Claude, Augustus John and Bandinelli, is set for its own lucrative auction - almost 20 years after he was brutally murdered in Italy

The late Hebborn, one of the world's most notorious art forgers, was so convincing that dealers sold his copies on as genuine originals, and much of his undetected work still hangs in galleries and museums around the world.

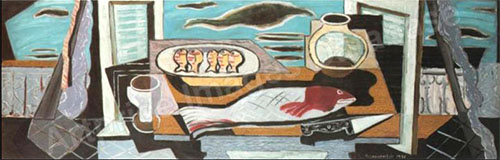

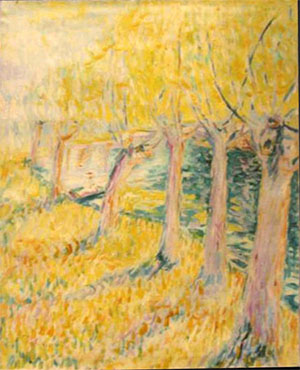

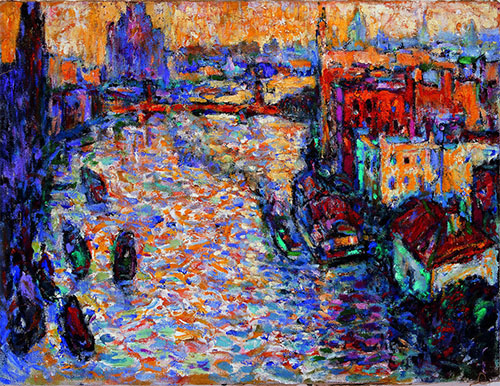

An oil on canvas painting in the style of Claude by master forger Eric Hebborn. He fooled art dealers, galleries and auction houses worldwide with his work in the style of Old Masters, and many of his works which were sold as originals still hang in museums and galleries

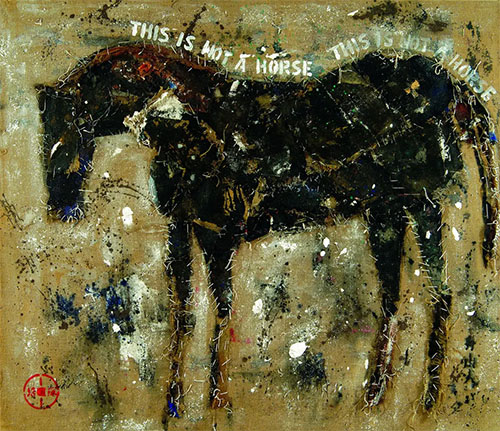

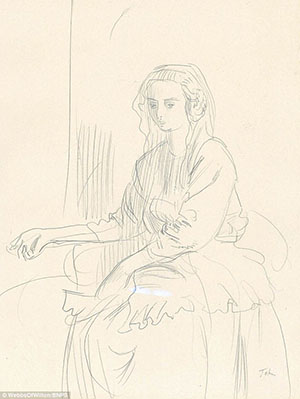

A drawing 'After' Michaelangelo - mimicking the style of old master. As well as the right paper and paint, he used glues prepared to a specific recipe to stop ink blotting and lines from bleeding

His pencil drawing of Augustus John's 'Young Girl', which is signed 'John' in the bottom right corner was sold at Christie's in London in in June 1989 as an original Augustus John and even has the auctioneer's stamp on the back of it from the time of sale

One is a pencil drawing of Augustus John's 'Young Girl', which is signed 'John' in the bottom right corner.

It was sold at Christie's in London in in June 1989 as an original Augustus John and even has the auctioneer's stamp on the back of it from the time of sale.

Now a collection of his works that expertly copy the style of Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Claude, Augustus John and Bandinelli are now being auctioned by Webbs of Wilton in Wiltshire.

Most of the Hebborn's work in the 1960s and 70s were original sketches made to resemble the style of historical artists rather than slightly altered copies of older work.

His deception was revealed in 1978 when a curator at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, US, examined two drawings from an established dealer of Old Master work and noticed they were on the same kind of paper.

Hebborn was murdered in Italy in 1996 and his killing remains unsolved. His deception was revealed in 1978 when a curator examined two drawings from an established dealer of old master work and noticed they were on the same kind of paper

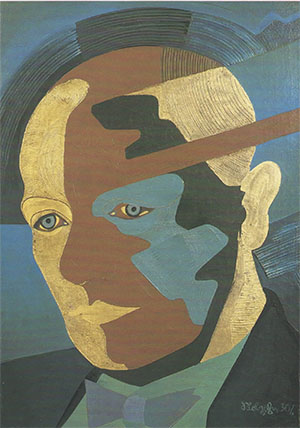

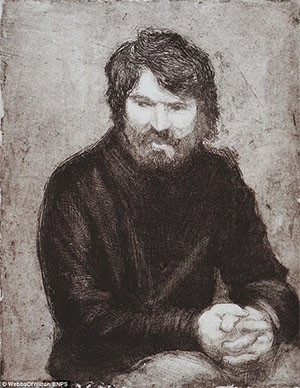

A self-portrait by Hebborn, an etching touched with sepia wash (1984). Most of the Hebborn's work in the 1960s and 70s were original sketches made to resemble the style of historical artists rather than slightly altered copies of older work

Hebborn confessed to making forged work in 1984 but insisted he had done nothing wrong and blamed the art dealers for allowing themselves to be deceived.

He was murdered in Italy in 1996 and his killing remains unsolved.

During his lifetime Hebborn sold many of works to his landlord, to London galleries and through auctioneers.

These items are from the collection of Hebborn's last agent and include a drawing after a design by Michelangelo, The Rape of Ganymede, which has an estimate of £600.

A similar drawing sold last October for £2,200, over 18 times its estimate.

An oil painting in the style of Claude is expected to do particularly well, with an estimate of £3,500. Hebborn was known as a dealer in 16th century drawings so he didn't create many oil paintings.

THE MISCHIEVOUS MASTER FORGER WHO DUPED EXPERTS FOR DECADES

Almost 20 years after his brutal death, Hebborn's forgeries still hang in the grandest galleries and auction houses of the world.

In just 61 years, he is believed to have forged more than 1,000 paintings and drawings that were wrongly attributed to artists from van Dyck to Rubens.

He was born in South Kensington in 1934, and soon became recognised as an art prodigy, despite what he claimed was a violent upbringing. He claimed to have been beaten by his mother, and he later set fire to his school.

He went to the Royal Academy and the British School at Rome, where he won all the prizes but was looked down on an despised by his contemporaries,

When he was in his late 20s his own art was not selling and so he embarked on his forging career - as much to poke fun at the art establishment than to make money.

In 1963, he copied a Whistler, the 19th-century American painter. He then forged an engraving by Brueghel, the 16th-century Flemish painter.

He began to stock up on 16th-century paper and bought an 18th-century paintbox and embarked on producing a line of ‘Old Masters’.

He used glues prepared to special recipes, of which he had more than 20, and offered his works to dealers, pretending he had no idea the pieces were the 'works' of the painters he was imitating.

His forgeries were eventually rumbled by Konrad Oberhuber, curator of the National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Hebborn was a homosexual and lived in Italy with his lover Graham David Smith.

He was killed on a rainy evening in Rome in January 1996, after he had dropped in for a few glasses of wine at a bar, before he told the proprietor he was going on to dinner.

A few hours later, he was found with a severe head wound in Piazza Trilussa, near the River Tiber.

He was operated on at a nearby hospital, but died the following day.

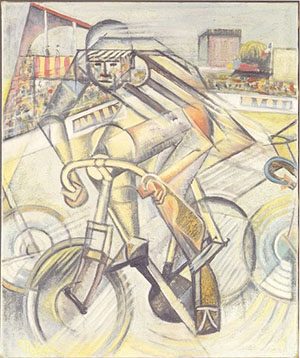

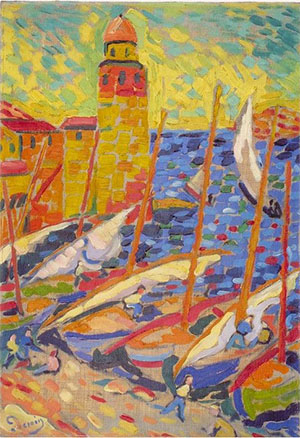

A sketch in the style of Rembrant. Hebborn had 20 recipes for ink. He took extracts from several oak trees, and ground them to a fine powder with a mortar and pestle

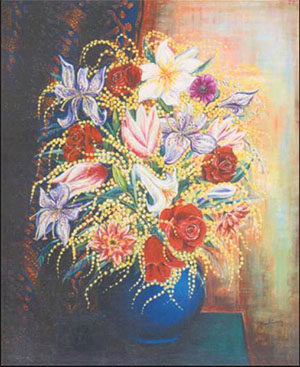

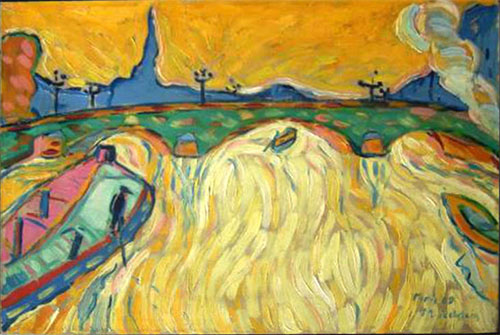

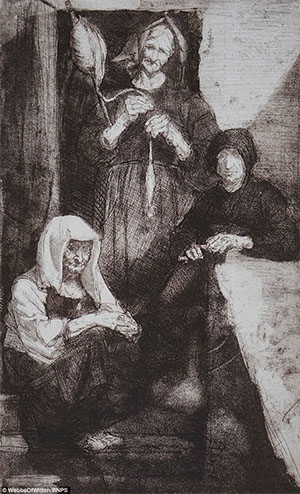

A piece entitled 'etching of three women' in his own style. An etching touched with wash, 1984. Hebborn himself was said to have launched his forgery career as a joke at the expense of art world snobs, who looked down on him

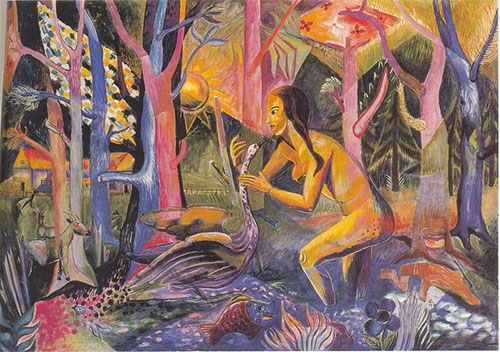

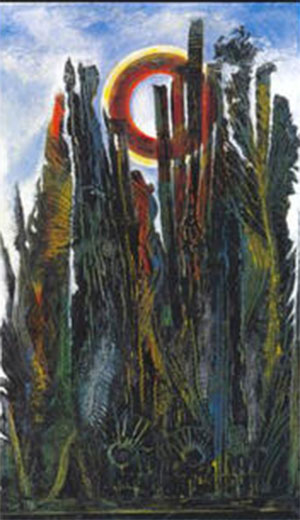

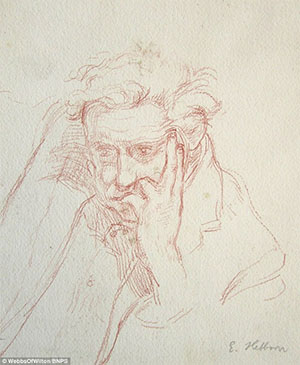

A portrait of Peter Greenham in red chalk, who Hebborn got to know while he was a student at Royal Academy Schools between 1954 and 1959. Hebborn greatly respected Greenham as a teacher, describing him later as 'retiring, courteous and amiable'

As well as the 23 drawings and three oil paintings, Webbs auctioneers are also selling manuscripts and books Hebborn wrote on the art of forging.

These include his notes for a lecture he titled 'The Gentle Art of Deceiving.'

Auctioneer Justin Bygott-Webb said: 'This is the second biggest collection of Hebborn items we're selling.

'The first sale was whatever was left in his studio, this one is much more competent. It has all come from his former agent who has decided to put his collection on the market.

'The reason Hebborn is so infamous is because he sold huge numbers of these works to the respected London dealer Colnaghi, which sold them to galleries and museums.

'He was known as a dealer in 16th century drawings but he was a rogue who took advantage of the art market and the greatest forger of the 20th century.

'He won all the prizes at the Royal Academy but he was looked down on and despised by his contemporaries.

'There's a video of him talking about why he did it and basically he thought it was a joke to pull the wool over the eyes of the art experts.

'A particular interesting piece is a portrait of a young girl which is a forgery of Augustus John but it actually sold at Christie's as an original and has the auction house's mark on it to prove it.

'This is one of the drawings that duped the art world.

'We think the Claude oil painting should do well. He didn't do many oils because he was known for dealing in Old Master drawings. It is also referred to in one of his books.

'Some of the drawings he has signed, the hearsay goes that he signed his forgeries at a later date to ensure he didn't get into trouble.'

The whole collection is expected to sell for £10,000 on Wednesday.