Partition of India

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 6/1/20

Partition of India

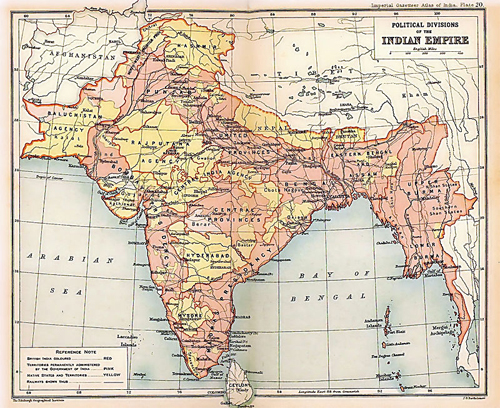

British Indian Empire in The Imperial Gazetteer of India, 1909. British India is shaded pink, the princely states yellow.

Date: August 1947

Location: British Raj, India and Pakistan

Outcome: Partition of British Indian Empire into independent dominions, India and Pakistan, and refugee crises

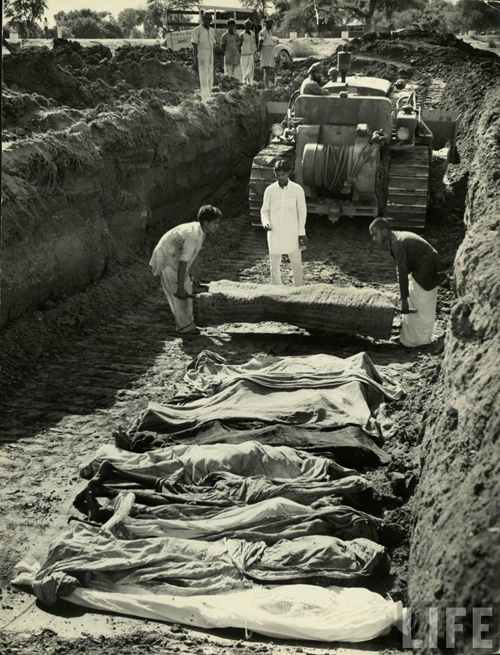

Deaths: 200,000 to 2 million,[1][a] 14 million displaced[2]

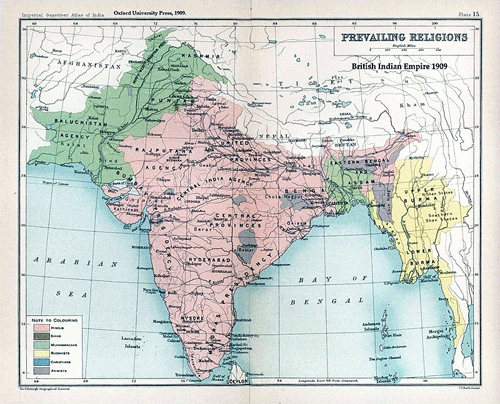

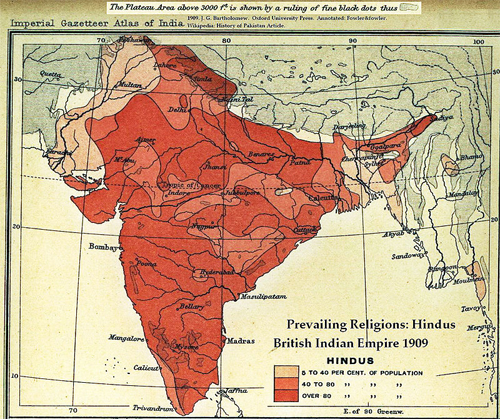

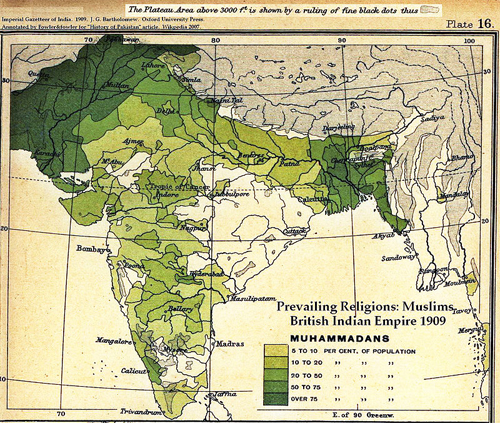

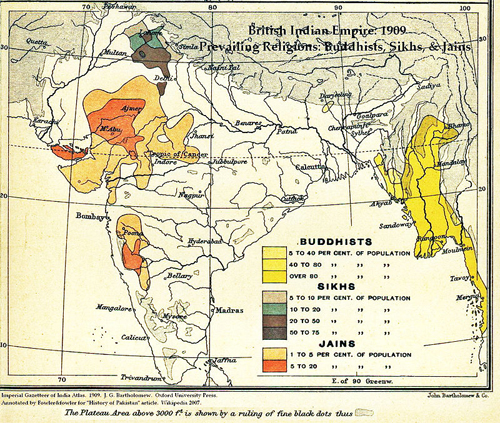

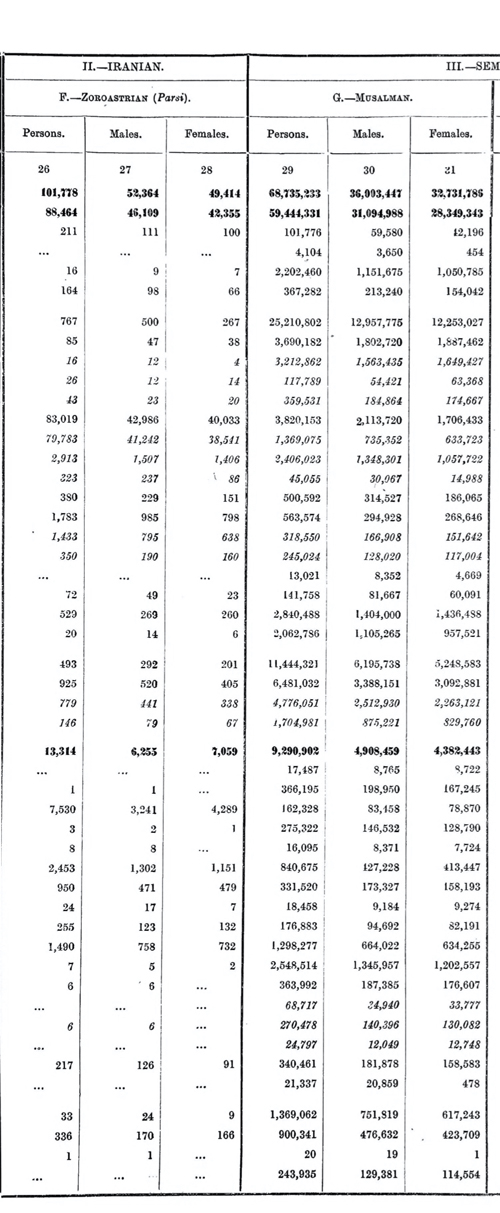

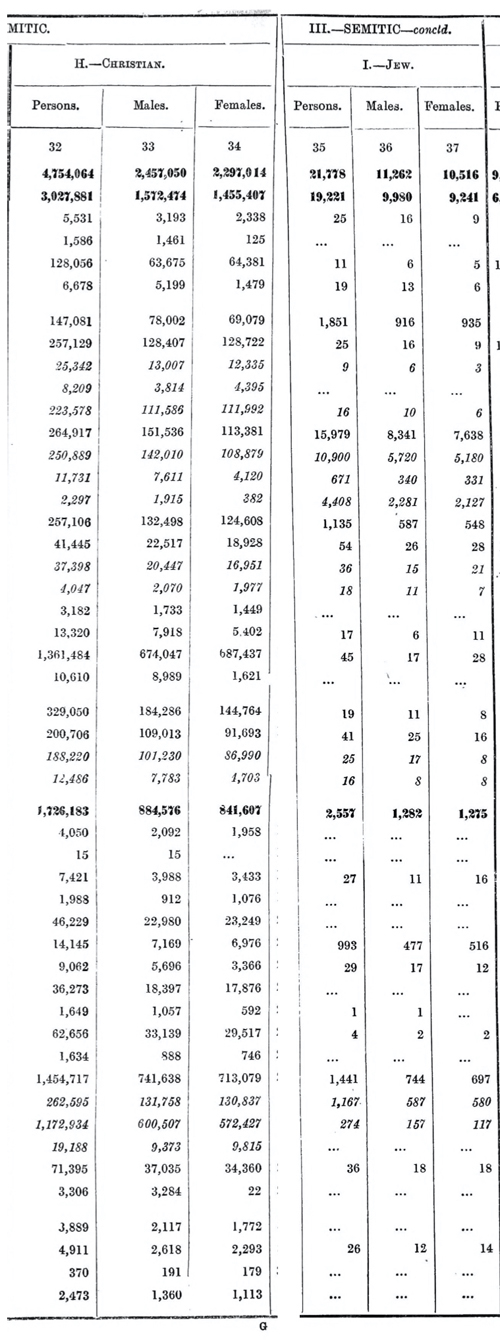

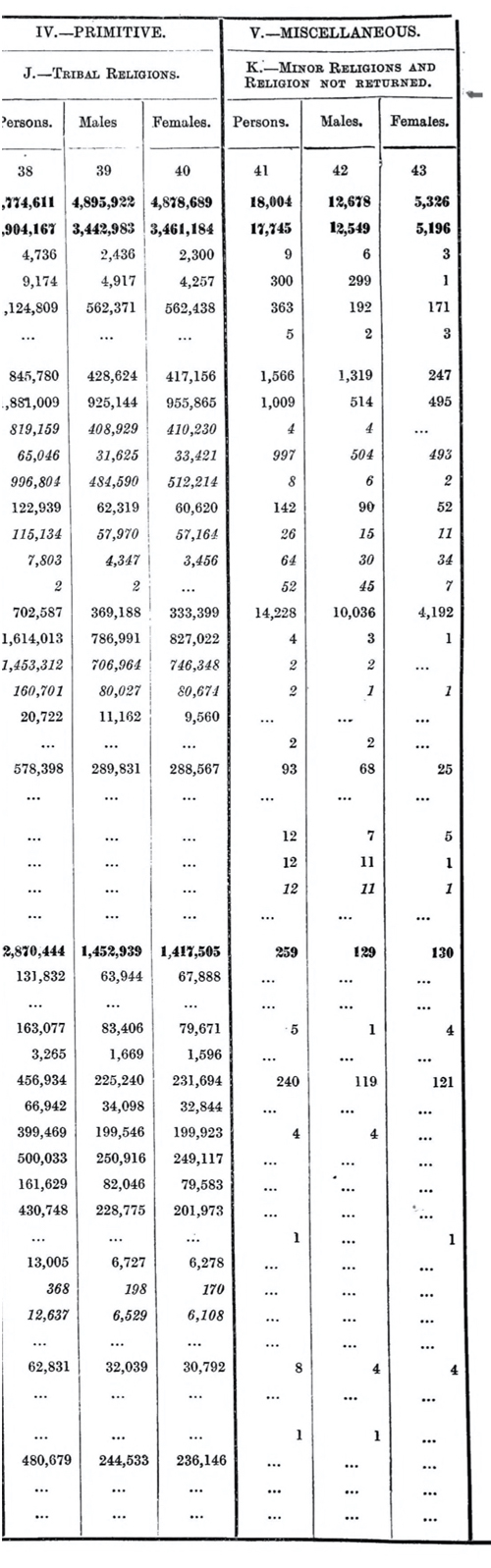

The prevailing religions of the British Indian Empire based on the Census of India, 1901

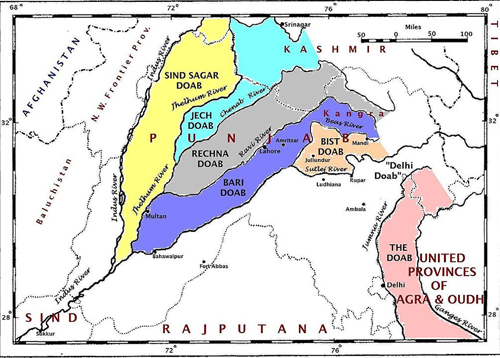

The Partition of India of 1947 was the division of British India[ b] into two independent dominion states, India and Pakistan by an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom.[3] India is today the Republic of India; Pakistan is today the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and the People's Republic of Bangladesh. The partition involved the division of two provinces, Bengal and Punjab, based on district-wise non-Muslim or Muslim majorities. The partition also saw the division of the British Indian Army, the Royal Indian Navy, the Indian Civil Service, the railways, and the central treasury. The partition was outlined in the Indian Independence Act 1947 and resulted in the dissolution of the British Raj, or Crown rule in India. The two self-governing countries of India and Pakistan legally came into existence at midnight on 15 August 1947.

The partition displaced between 10–12 million people along religious lines, creating overwhelming refugee crises in the newly constituted dominions. There was large-scale violence, with estimates of loss of life accompanying or preceding the partition disputed and varying between several hundred thousand and two million.[1][c] The violent nature of the partition created an atmosphere of hostility and suspicion between India and Pakistan that plagues their relationship to the present.

The term partition of India does not cover the secession of Bangladesh from Pakistan in 1971, nor the earlier separations of Burma (now Myanmar) and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) from the administration of British India.[d] The term also does not cover the political integration of princely states into the two new dominions, nor the disputes of annexation or division arising in the princely states of Hyderabad, Junagadh, and Jammu and Kashmir, though violence along religious lines did break out in some princely states at the time of the partition. It does not cover the incorporation of the enclaves of French India into India during the period 1947–1954, nor the annexation of Goa and other districts of Portuguese India by India in 1961. Other contemporaneous political entities in the region in 1947, Sikkim, Bhutan, Nepal, and the Maldives were unaffected by the partition.[e]

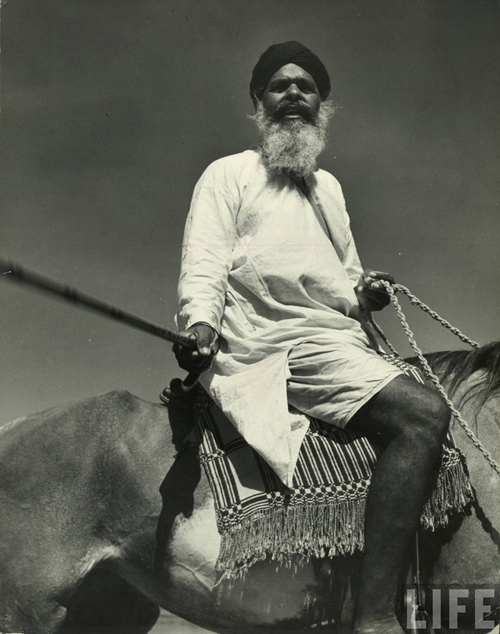

Among princely states, the violence was often highly organised with the involvement or complicity of the rulers. It is believed that in the Sikh states (except for Jind and Kapurthala) the Maharajas were complicit in the ethnic cleansing of Muslims, while other Maharajas such as those of Patiala, Faridkot, and Bharatpur were heavily involved in ordering them. The ruler of Bharatpur is said to have witnessed the ethnic cleansing of his population, especially at places such as Deeg.[7]

Background

Partition of Bengal (1905)

Main article: Partition of Bengal (1905)

1909 Percentage of Hindus.

1909 Percentage of Muslims.

1909 Percentage of Sikhs, Buddhists, and Jains.

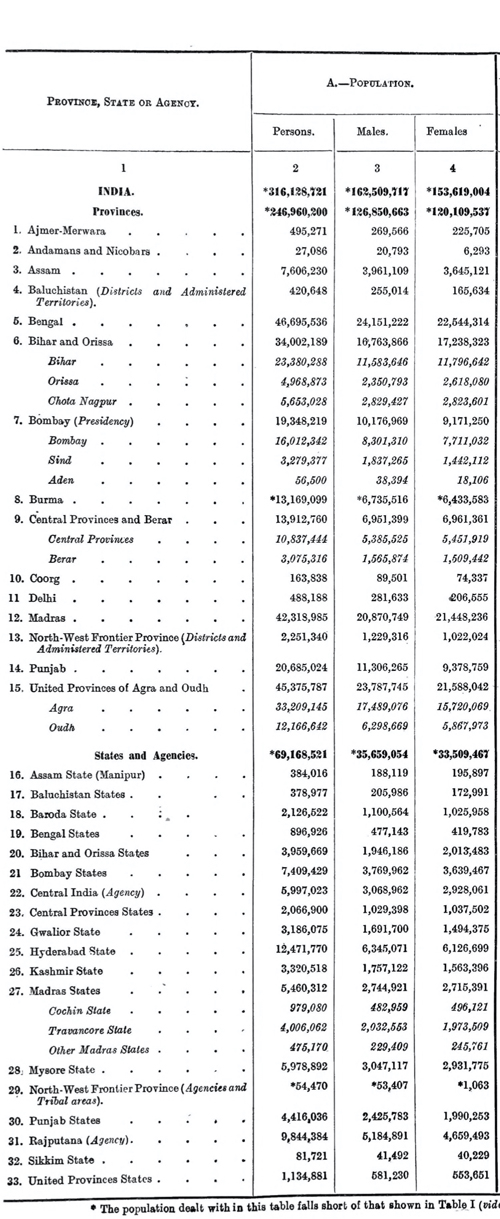

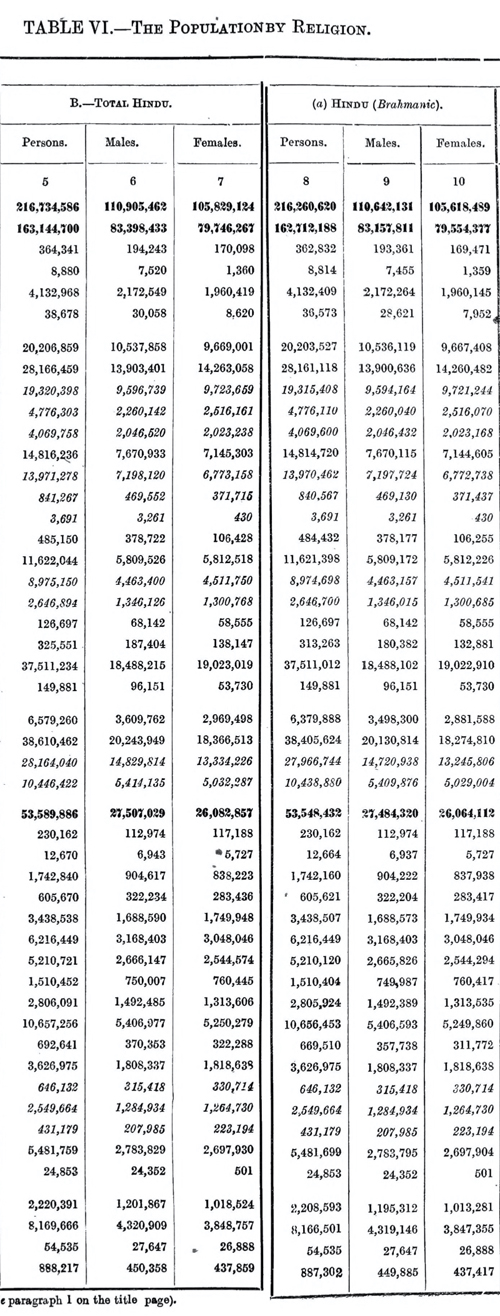

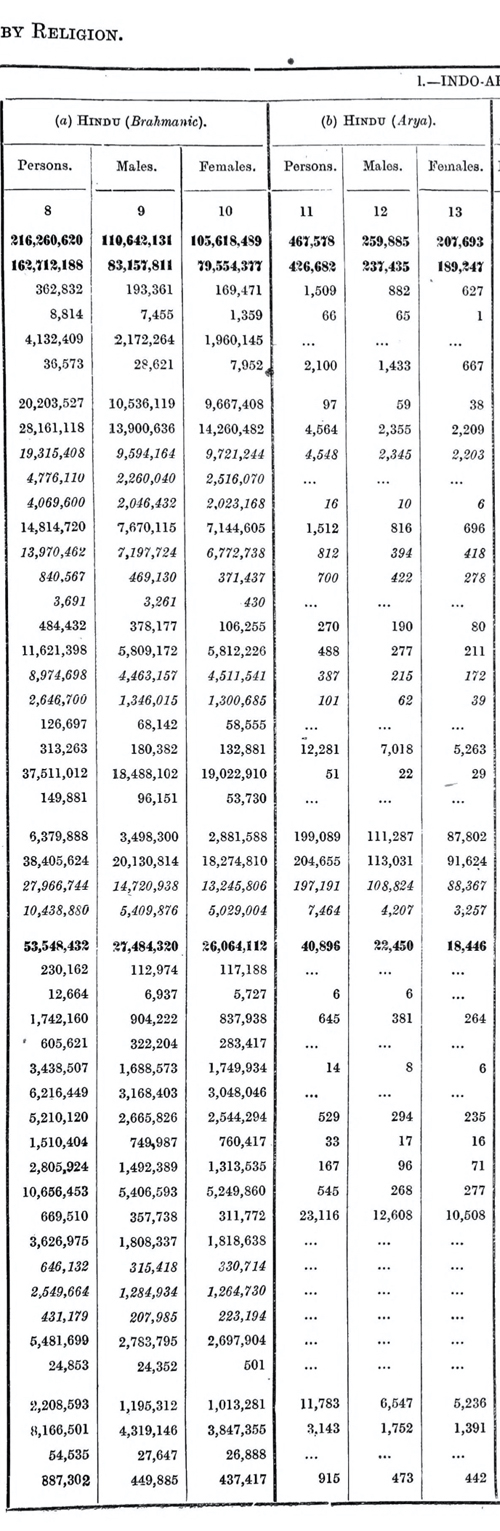

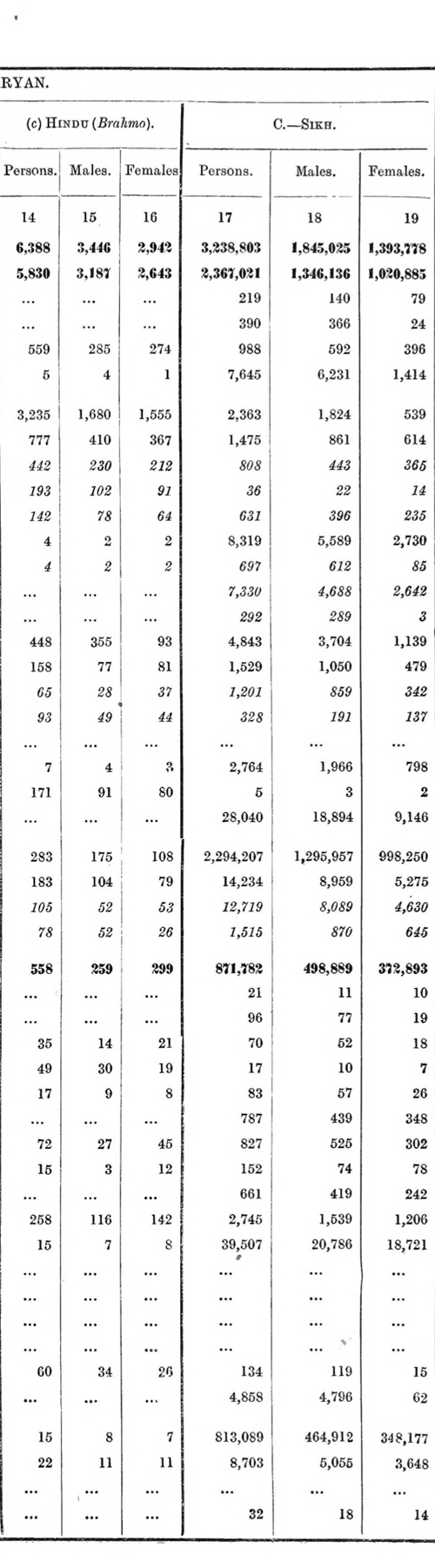

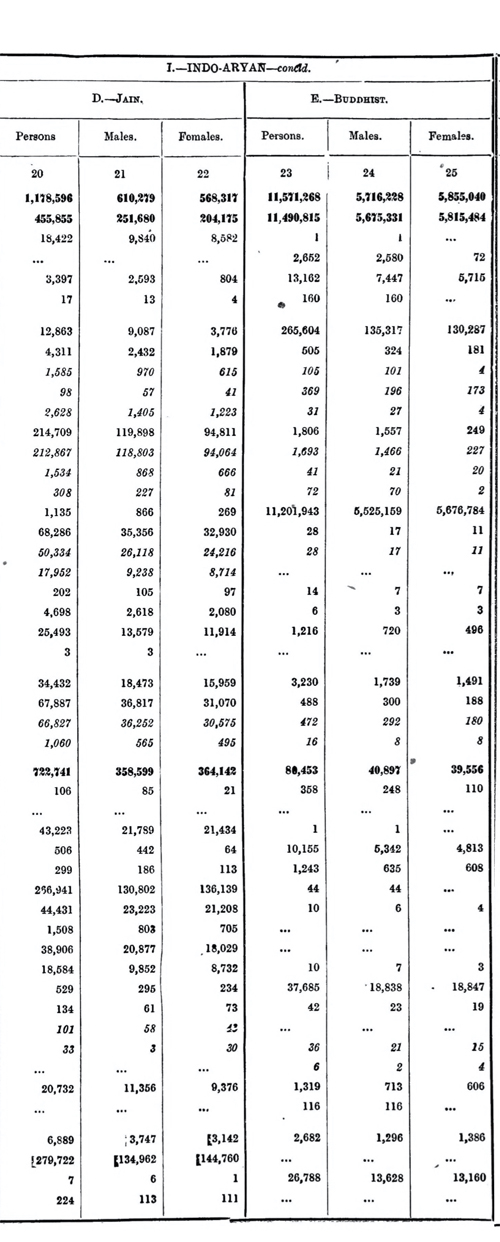

The 1921 Census of British India shows 69 million Muslims and 217 million Hindus out of a total population of 316 million.

In 1905, the viceroy, Lord Curzon, in his second term, divided the largest administrative subdivision in British India, the Bengal Presidency, into the Muslim-majority province of East Bengal and Assam and the Hindu-majority province of Bengal (present-day Indian states of West Bengal, Bihar, Jharkhand and Odisha).[8] Curzon's act, the Partition of Bengal—which some considered administratively felicitous, and, which had been contemplated by various colonial administrations since the time of Lord William Bentinck, but never acted upon—was to transform nationalist politics as nothing else before it.[8] The Hindu elite of Bengal, among them many who owned land in East Bengal that was leased out to Muslim peasants, protested strongly. The large Bengali Hindu middle-class (the Bhadralok), upset at the prospect of Bengalis being outnumbered in the new Bengal province by Biharis and Oriyas, felt that Curzon's act was punishment for their political assertiveness.[8] The pervasive protests against Curzon's decision took the form predominantly of the Swadeshi ("buy Indian") campaign and involved a boycott of British goods. Sporadically—but flagrantly—the protesters also took to political violence that involved attacks on civilians.[9] The violence, however, was not effective, as most planned attacks were either pre-empted by the British or failed.[10] The rallying cry for both types of protest was the slogan Bande Mataram (Bengali, lit: "Hail to the Mother"), the title of a song by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, which invoked a mother goddess, who stood variously for Bengal, India, and the Hindu goddess Kali.[11] The unrest spread from Calcutta to the surrounding regions of Bengal when Calcutta's English-educated students returned home to their villages and towns.[12] The religious stirrings of the slogan and the political outrage over the partition were combined as young men, in groups such as Jugantar, took to bombing public buildings, staging armed robberies,[10] and assassinating British officials.[11] Since Calcutta was the imperial capital, both the outrage and the slogan soon became known nationally.[11]

The overwhelming, but predominantly Hindu, protest against the partition of Bengal and the fear of reforms favouring the Hindu majority, now led the Muslim elite in India to meet with the new viceroy Lord Minto in 1906 and ask for separate electorates for Muslims. In conjunction, they demanded proportional legislative representation reflecting both their status as former rulers and their record of cooperating with the British. This led, in December 1906, to the founding of the All-India Muslim League in Dacca. Although Curzon by now had resigned his position over a dispute with his military chief Lord Kitchener and returned to England, the League was in favor of his partition plan. The Muslim elite's position, which was reflected in the League's position, had crystallized gradually over the previous three decades, beginning with the 1871 Census of British India, which had first estimated the populations in regions of Muslim majority.[13] For his part, Curzon's desire to court the Muslims of East Bengal had arisen from British anxieties ever since the 1871 census, and in light of the history of Muslims fighting them in the 1857 Mutiny and the Second Anglo-Afghan War.[13] In the three decades since that census, Muslim leaders across northern India, had intermittently experienced public animosity from some of the new Hindu political and social groups.[13] The Arya Samaj, for example, had not only supported Cow Protection Societies in their agitation,[14] but also—distraught at the 1871 Census's Muslim numbers—organized "reconversion" events for the purpose of welcoming Muslims back to the Hindu fold.[13] In the United Provinces, Muslims became anxious in the late 19th century Hindu political representation increased, and Hindus were politically mobilized in the Hindi-Urdu controversy and the anti-cow-killing riots of 1893.[15] In 1905 Muslim fears increased when Tilak and Lajpat Rai attempted to rise to leadership positions in the Congress, and the Congress itself rallied around the symbolism of Kali.[13] It was not lost on many Muslims, for example, that the rallying cry, "Bande Mataram," had first appeared in the novel Anandmath in which Hindus had battled their Muslim oppressors.[16] Lastly, the Muslim elite, and among it Dacca Nawab, Khwaja Salimullah, who hosted the League's first meeting in his mansion in Shahbag, was aware that a new province with a Muslim majority would directly benefit Muslims aspiring to political power.[16]

World War I, Lucknow Pact: 1914–1918

Indian medical orderlies attending to wounded soldiers with the Mesopotamian Expeditionary Force in Mesopotamia during World War I

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (seated in the carriage, on the right, eyes downcast, with black flat-top hat) receives a big welcome in Karachi in 1916 after his return to India from South Africa

Muhammad Ali Jinnah, seated, third from the left, was a supporter of the Lucknow Pact, which, in 1916, ended the three-way rift between the Extremists, the Moderates and the League

World War I would prove to be a watershed in the imperial relationship between Britain and India. 1.4 million Indian and British soldiers of the British Indian Army would take part in the war, and their participation would have a wider cultural fallout: news of Indian soldiers fighting and dying with British soldiers, as well as soldiers from dominions like Canada and Australia, would travel to distant corners of the world both in newsprint and by the new medium of the radio.[17] India's international profile would thereby rise and would continue to rise during the 1920s.[17] It was to lead, among other things, to India, under its name, becoming a founding member of the League of Nations in 1920 and participating, under the name, "Les Indes Anglaises" (British India), in the 1920 Summer Olympics in Antwerp.[18] Back in India, especially among the leaders of the Indian National Congress, it would lead to calls for greater self-government for Indians.[17]

The 1916 Lucknow Session of the Congress was also the venue of an unanticipated mutual effort by the Congress and the Muslim League, the occasion for which was provided by the wartime partnership between Germany and Turkey. Since the Turkish Sultan, or Khalifah, also had sporadically claimed guardianship of the Islamic holy sites of Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem, and since the British and their allies were now in conflict with Turkey, doubts began to increase among some Indian Muslims about the "religious neutrality" of the British, doubts that had already surfaced as a result of the reunification of Bengal in 1911, a decision that was seen as ill-disposed to Muslims.[19] In the Lucknow Pact, the League joined the Congress in the proposal for greater self-government that was campaigned for by Tilak and his supporters; in return, the Congress accepted separate electorates for Muslims in the provincial legislatures as well as the Imperial Legislative Council. In 1916, the Muslim League had anywhere between 500 and 800 members and did not yet have its wider following among Indian Muslims of later years; in the League itself, the pact did not have unanimous backing, having largely been negotiated by a group of "Young Party" Muslims from the United Provinces (UP), most prominently, the brothers Mohammad and Shaukat Ali, who had embraced the Pan-Islamic cause.[19] However, it did have the support of a young lawyer from Bombay, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who was later to rise to leadership roles in both the League and the Indian independence movement. In later years, as the full ramifications of the pact unfolded, it was seen as benefiting the Muslim minority elites of provinces like UP and Bihar more than the Muslim majorities of Punjab and Bengal. At the time, the "Lucknow Pact" was an important milestone in nationalistic agitation and was seen so by the British.[19]

Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms: 1919

Secretary of State for India, Montagu and Viceroy Lord Chelmsford presented a report in July 1918 after a long fact-finding trip through India the previous winter.[20] After more discussion by the government and parliament in Britain, and another tour by the Franchise and Functions Committee to identify who among the Indian population could vote in future elections, the Government of India Act of 1919 (also known as the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms) was passed in December 1919.[20] The new Act enlarged both the provincial and Imperial legislative councils and repealed the Government of India's recourse to the "official majority" in unfavourable votes.[20] Although departments like defence, foreign affairs, criminal law, communications, and income-tax were retained by the Viceroy and the central government in New Delhi, other departments like public health, education, land-revenue, local self-government were transferred to the provinces.[20] The provinces themselves were now to be administered under a new dyarchical system, whereby some areas like education, agriculture, infrastructure development, and local self-government became the preserve of Indian ministers and legislatures, and ultimately the Indian electorates, while others like irrigation, land-revenue, police, prisons, and control of media remained within the purview of the British governor and his executive council.[20] The new Act also made it easier for Indians to be admitted into the civil service and the army officer corps.

A greater number of Indians were now enfranchised, although, for voting at the national level, they constituted only 10% of the total adult male population, many of whom were still illiterate.[20] In the provincial legislatures, the British continued to exercise some control by setting aside seats for special interests they considered cooperative or useful. In particular, rural candidates, generally sympathetic to British rule and less confrontational, were assigned more seats than their urban counterparts.[20] Seats were also reserved for non-Brahmins, landowners, businessmen, and college graduates. The principle of "communal representation," an integral part of the Minto-Morley Reforms, and more recently of the Congress-Muslim League Lucknow Pact, was reaffirmed, with seats being reserved for Muslims, Sikhs, Indian Christians, Anglo-Indians, and domiciled Europeans, in both provincial and Imperial legislative councils.[20] The Montagu-Chelmsford reforms offered Indians the most significant opportunity yet for exercising legislative power, especially at the provincial level; however, that opportunity was also restricted by the still limited number of eligible voters, by the small budgets available to provincial legislatures, and by the presence of rural and special interest seats that were seen as instruments of British control.[20]

Two-nation theory

Main article: Two-nation theory

The two-nation theory is the ideology that the primary identity and unifying denominator of Muslims in the Indian subcontinent is their religion, rather than their language or ethnicity, and therefore Indian Hindus and Muslims are two distinct nations regardless of commonalities.[21][22] The two-nation theory was a founding principle of the Pakistan Movement (i.e., the ideology of Pakistan as a Muslim nation-state in South Asia), and the partition of India in 1947.[23]

The Pakistan Movement or Tehrik-e-Pakistan (Urdu: تحریک پاکستان – Taḥrīk-i Pākistān) was a political movement in the first half of the 20th century that aimed for and succeeded in the creation of the Dominion of Pakistan from the Muslim-majority areas of British India.

Pakistan Movement started originally as the Aligarh Movement, and as a result, the British Indian Muslims began to develop a secular political identity. Soon thereafter, the All India Muslim League was formed, which perhaps marked the beginning of the Pakistan Movement. Many of the top leadership of the movement were educated in Great Britain, with many of them educated at the Aligarh Muslim University. Many graduates of the Dhaka University soon also joined.

The Pakistan Movement was a part of the Indian independence movement, but eventually it also sought to establish a new nation-state that protected the political interests of the Indian Muslims.

-- Pakistan Movement, by Wikipedia

The ideology that religion is the determining factor in defining the nationality of Indian Muslims was undertaken by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who termed it as the awakening of Muslims for the creation of Pakistan.[24] It is also a source of inspiration to several Hindu nationalist organizations, with causes as varied as the redefinition of Indian Muslims as non-Indian foreigners and second-class citizens in India, the expulsion of all Muslims from India, establishment of a legally Hindu state in India, prohibition of conversions to Islam, and the promotion of conversions or reconversions of Indian Muslims to Hinduism.[25][26][27][28]

The Hindu Mahasabha leader Lala Lajpat Rai was one of the first persons to demand to bifurcate India by Muslim and non-Muslim population. He wrote in The Tribune of 14 December 1924:

Under my scheme the Muslims will have four Muslim States: (1) The Pathan Province or the North-West Frontier; (2) Western Punjab (3) Sindh and (4) Eastern Bengal. If there are small Muslim communities in any other part of India, sufficiently large to form a province, they should be similarly constituted. But it should be distinctly understood that this is not a united India. It means a clear partition of India into a Muslim India and a non-Muslim India.[29]

There are varying interpretations of the two-nation theory, based on whether the two postulated nationalities can coexist in one territory or not, with radically different implications. One interpretation argued for sovereign autonomy, including the right to secede, for Muslim-majority areas of the Indian subcontinent, but without any transfer of populations (i.e., Hindus and Muslims would continue to live together). A different interpretation contends that Hindus and Muslims constitute "two distinct and frequently antagonistic ways of life and that therefore they cannot coexist in one nation."[30] In this version, a transfer of populations (i.e., the total removal of Hindus from Muslim-majority areas and the total removal of Muslims from Hindu-majority areas) was a desirable step towards a complete separation of two incompatible nations that "cannot coexist in a harmonious relationship." [31][32]

Opposition to the theory has come from two sources. The first is the concept of a single Indian nation, of which Hindus and Muslims are two intertwined communities.[33] This is a founding principle of the modern, officially secular, Republic of India. Even after the formation of Pakistan, debates on whether Muslims and Hindus are distinct nationalities or not continued in that country as well.[34] The second source of opposition is the concept that while Indians are not one nation, neither are the Muslims or Hindus of the subcontinent, and it is instead the relatively homogeneous provincial units of the subcontinent which are true nations and deserving of sovereignty; the Baloch has presented this view,[35] Sindhi,[36] and Pashtun[37] sub-nationalities of Pakistan and the Assamese[38] and Punjabi[39] sub-nationalities of India.

Muslim homeland, provincial elections, World War II, Lahore Resolution: 1930–1945

Jawaharlal Nehru, Sarojini Naidu, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, and Maulana Azad at the 1940 Ramgarh session of the Congress in which Azad was elected president for the second time

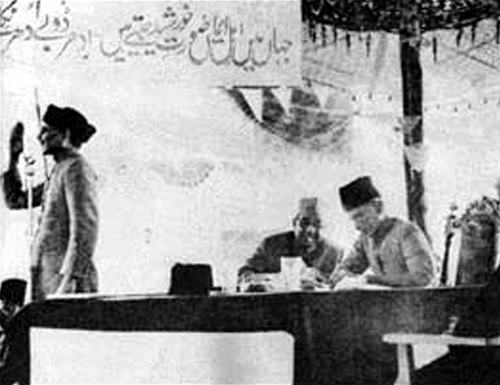

Chaudhari Khaliquzzaman (left) seconding the 1940 Lahore Resolution of the All-India Muslim League with Jinnah (right) presiding, and Liaquat Ali Khan centre

Although Choudhry Rahmat Ali had in 1933 produced a pamphlet, Now or never, in which the term "Pakistan", "the land of the pure", comprising the Punjab, North West Frontier Province (Afghania), Kashmir, Sindh, and Balochistan, was coined for the first time, the pamphlet did not attract political attention.[40] A little later, a Muslim delegation to the Parliamentary Committee on Indian Constitutional Reforms gave short shrift to the Pakistan idea, calling it "chimerical and impracticable".[40] In 1932, the British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald accepted Dr. Ambedkar's [Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar] demand for the “Depressed Classes” to have separate representation in the central and provincial legislatures. The Muslim League favoured the award as it had the potential to weaken the Hindu caste leadership. However, Mahatma Gandhi, who was seen as a leading advocate for Dalit [untouchable] rights, went on a fast to persuade the British to repeal the award. Ambedkar had to back down when it seemed Gandhi's life was threatened.[41]

Two years later, the Government of India Act 1935 introduced provincial autonomy, increasing the number of voters in India to 35 million.[42] More significantly, law and order issues were for the first time devolved from British authority to provincial governments headed by Indians.[42] This increased Muslim anxieties about eventual Hindu domination.[42] In the 1937 Indian provincial elections, the Muslim League turned out its best performance in Muslim-minority provinces such as the United Provinces, where it won 29 of the 64 reserved Muslim seats.[42] However, in the Muslim-majority regions of the Punjab and Bengal regional parties outperformed the League.[42] In the Punjab, the Unionist Party of Sikandar Hayat Khan, won the elections and formed a government, with the support of the Indian National Congress and the Shiromani Akali Dal, which lasted five years.[42] In Bengal, the League had to share power in a coalition headed by A. K. Fazlul Huq, the leader of the Krishak Praja Party.[42]

The Congress, on the other hand, with 716 wins in the total of 1585 provincial assemblies seats, was able to form governments in 7 out of the 11 provinces of British India.[42] In its manifesto, the Congress maintained that religious issues were of lesser importance to the masses than economic and social issues. However, the election revealed that the Congress had contested just 58 out of the total 482 Muslim seats, and of these, it won in only 26.[42] In UP, where the Congress won, it offered to share power with the League on condition that the League stop functioning as a representative only of Muslims, which the League refused.[42] This proved to be a mistake as it alienated Congress further from the Muslim masses. Besides, the new UP provincial administration promulgated cow protection and the use of Hindi.[42] The Muslim elite in UP was further alienated, when they saw chaotic scenes of the new Congress Raj, in which rural people who sometimes turned up in large numbers in Government buildings, were indistinguishable from the administrators and the law enforcement personnel.[43]

The Muslim League conducted its investigation into the conditions of Muslims under Congress-governed provinces.[44] The findings of such investigations increased fear among the Muslim masses of future Hindu domination.[44] The view that Muslims would be unfairly treated in an independent India dominated by the Congress was now a part of the public discourse of Muslims.[44] With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, the viceroy, Lord Linlithgow, declared war on India's behalf without consulting Indian leaders, leading the Congress provincial ministries to resign in protest.[44] The Muslim League, which functioned under state patronage,[45] in contrast, organized "Deliverance Day", celebrations (from Congress dominance) and supported Britain in the war effort.[44] When Linlithgow met with nationalist leaders, he gave the same status to Jinnah as he did to Gandhi, and a month later described the Congress as a "Hindu organization."[45]

In March 1940, in the League's annual three-day session in Lahore, Jinnah gave a two-hour speech in English, in which were laid out the arguments of the Two-nation theory, stating, in the words of historians Talbot and Singh, that "Muslims and Hindus ... were irreconcilably opposed monolithic religious communities and as such, no settlement could be imposed that did not satisfy the aspirations of the former."[44] On the last day of its session, the League passed, what came to be known as the Lahore Resolution, sometimes also "Pakistan Resolution," [44] demanding that "the areas in which the Muslims are numerically in the majority as in the North-Western and Eastern zones of India should be grouped to constitute independent states in which the constituent units shall be autonomous and sovereign." Though it had been founded more than three decades earlier, the League would gather support among South Asian Muslims only during the Second World War.[46]

Viceroy Linlithgow proposed in August 1940 that India be granted a Dominion status after the war. Having not taken the Pakistan idea seriously, Linlithgow supposed that what Jinnah wanted was a non-federal arrangement without Hindu domination. To allay Muslim fears of Hindu domination, the 'August offer' was accompanied by the promise that a future constitution would consider the views of minorities.[47] Neither the Congress nor the Muslim League were satisfied with the offer, and both rejected it in September. The Congress once again started a program of civil disobedience.[48]

In March 1942, with the Japanese fast moving up the Malayan Peninsula after the Fall of Singapore,[45] and with the Americans supporting independence for India,[49] Winston Churchill, the wartime Prime Minister of Britain, sent Sir Stafford Cripps, the leader of the House of Commons, with an offer of dominion status to India at the end of the war in return for the Congress's support for the war effort.[50] Not wishing to lose the support of the allies they had already secured—the Muslim League, Unionists of Punjab, and the Princes—Cripps's offer included a clause stating that no part of the British Indian Empire would be forced to join the post-war Dominion. The League rejected the offer, seeing this clause as insufficient in meeting the principle of Pakistan.[51] As a result of that proviso, the proposals were also rejected by the Congress, which, since its founding as a polite group of lawyers in 1885,[52] saw itself as the representative of all Indians of all faiths.[50] After the arrival in 1920 of Gandhi, the pre-eminent strategist of Indian nationalism,[53] the Congress had been transformed into a mass nationalist movement of millions.[52] In August 1942, the Congress launched the Quit India Resolution which asked for drastic constitutional changes, which the British saw as the most serious threat to their rule since the Indian rebellion of 1857.[50] With their resources and attention already spread thin by a global war, the nervous British immediately jailed the Congress leaders and kept them in jail until August 1945,[54] whereas the Muslim League was now free for the next three years to spread its message.[45] Consequently, the Muslim League's ranks surged during the war, with Jinnah himself admitting, "The war which nobody welcomed proved to be a blessing in disguise."[55] Although there were other important national Muslim politicians such as Congress leader Abul Kalam Azad, and influential regional Muslim politicians such as A. K. Fazlul Huq of the leftist Krishak Praja Party in Bengal, Sikander Hyat Khan of the landlord-dominated Punjab Unionist Party, and Abd al-Ghaffar Khan of the pro-Congress Khudai Khidmatgar (popularly, "red shirts") in the North West Frontier Province, the British were to increasingly see the League as the main representative of Muslim India.[56] The Muslim League's demand for Pakistan pitted it against the British and Congress.[57]

1946 Election, Cabinet Mission, Direct Action Day, Plan for Partition, Independence: 1946–1947

Further information: Indian general election, 1945 and Indian provincial elections, 1946

Members of the 1946 Cabinet Mission to India meeting Muhammad Ali Jinnah. On the extreme left is Lord Pethick Lawrence; on the extreme right, Sir Stafford Cripps.

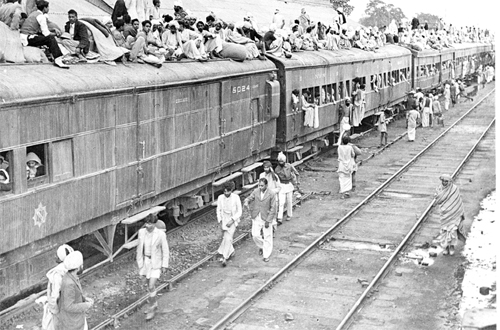

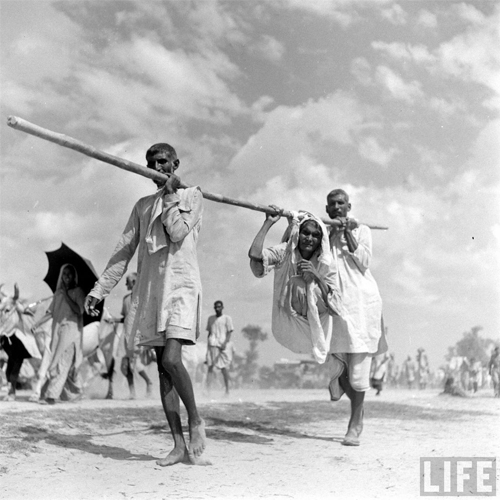

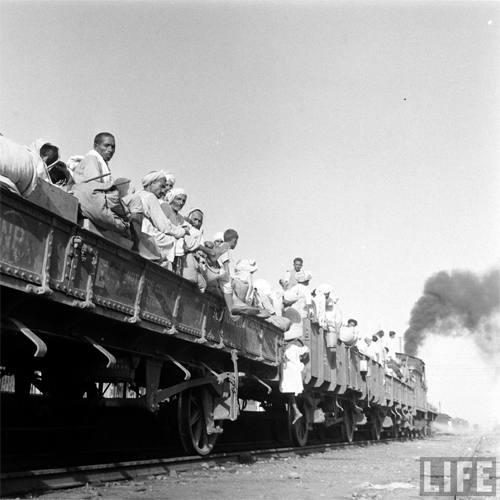

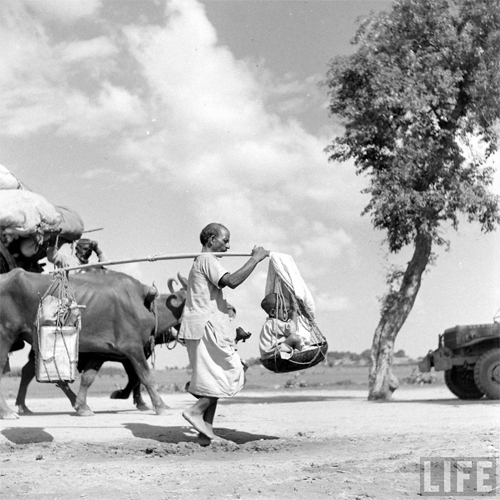

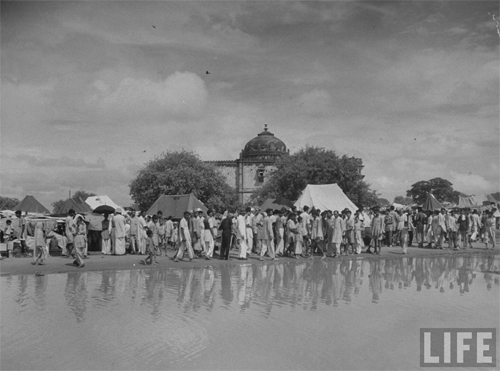

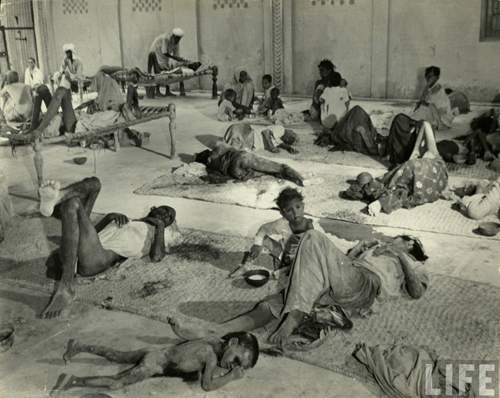

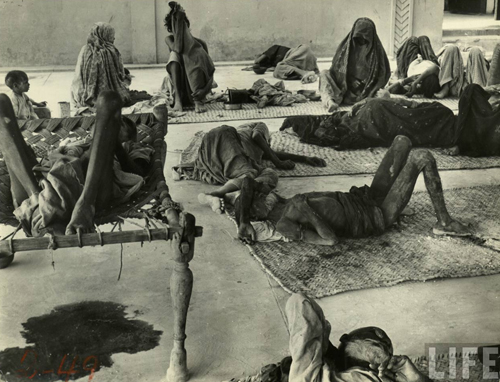

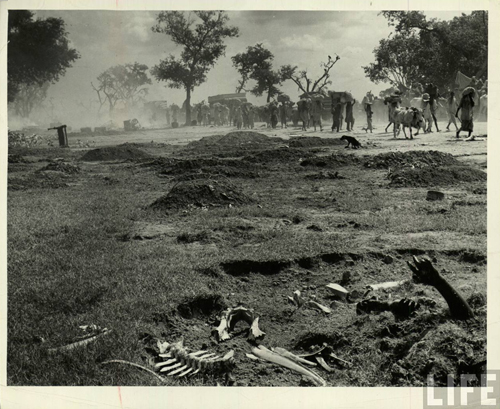

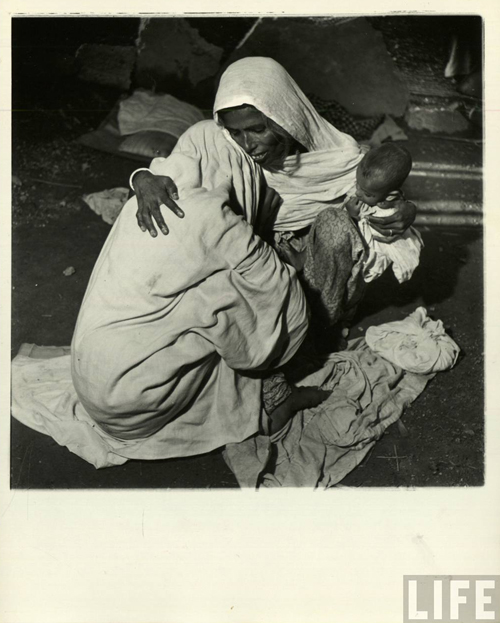

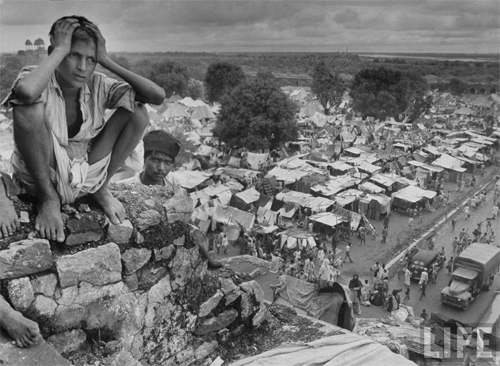

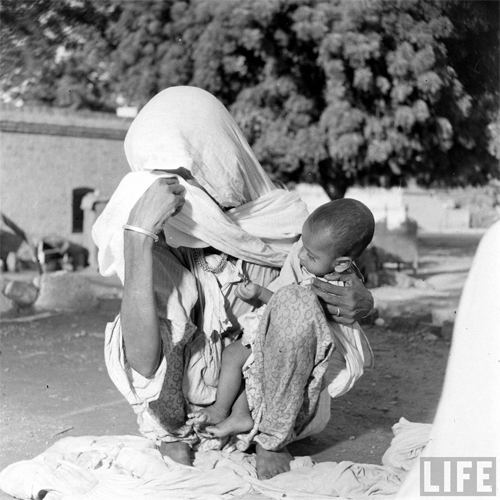

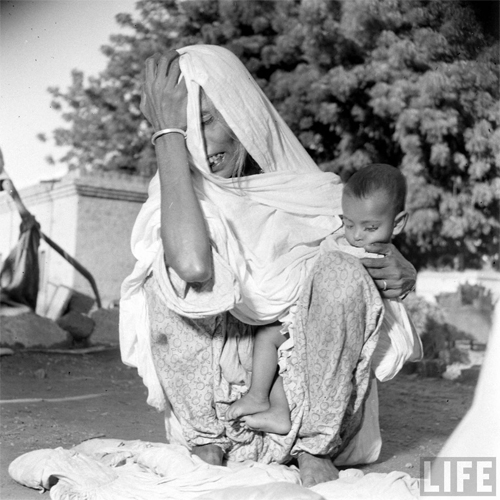

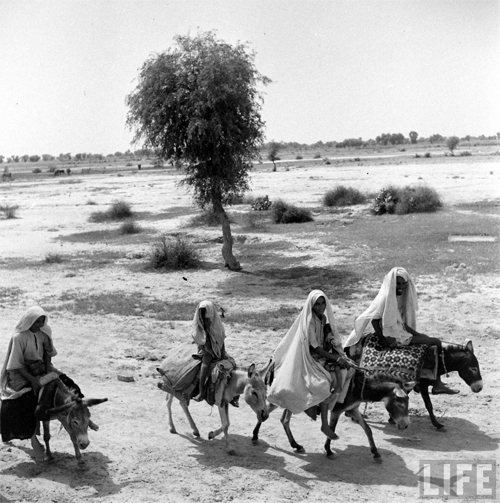

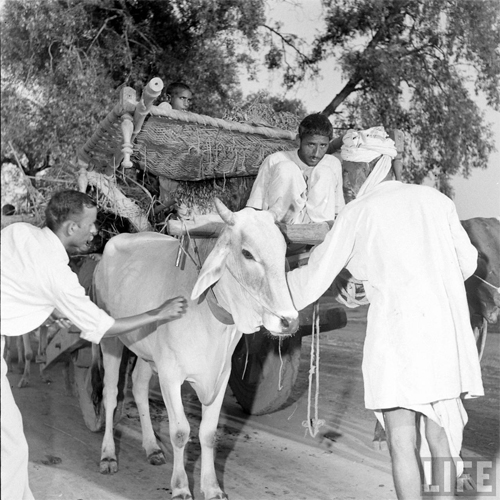

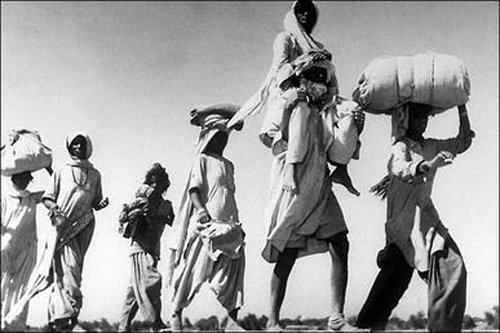

An aged and abandoned Muslim couple and their grandchildren are sitting by the roadside on this arduous journey. "The old man is dying of exhaustion. The caravan has gone on," wrote Bourke-White.

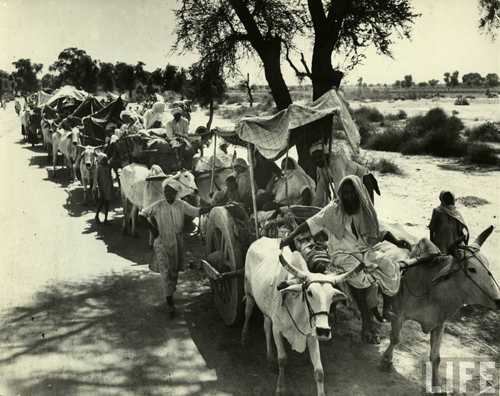

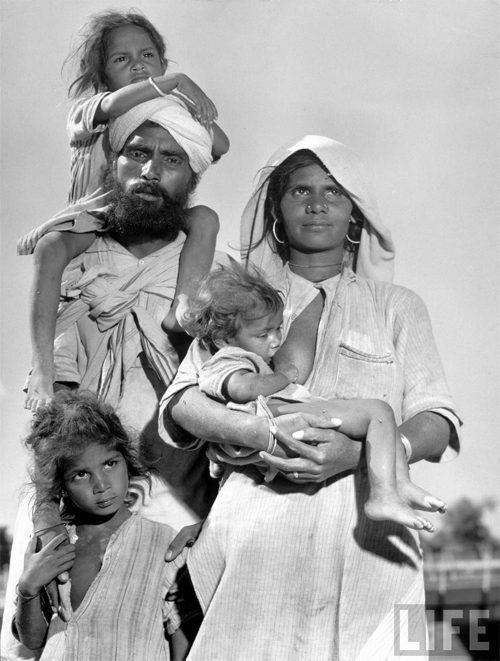

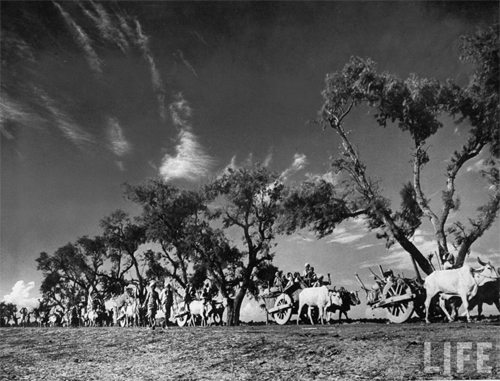

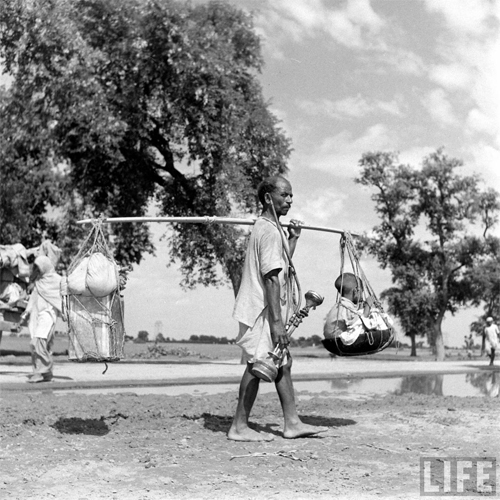

An old Sikh man is carrying his wife. Over 10 million people were uprooted from their homeland and traveled on foot, bullock carts and trains to their promised new home.

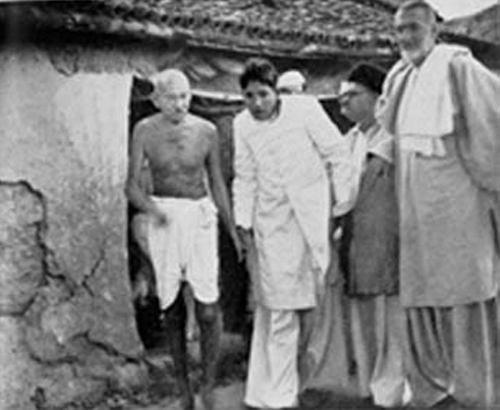

Gandhi in Bela, Bihar, after attacks on Muslims, 28 March 1947.

In January 1946 mutinies broke out in the armed services, starting with RAF servicemen frustrated with their slow repatriation to Britain.[58] The mutinies came to a head with mutiny of the Royal Indian Navy in Bombay in February 1946, followed by others in Calcutta, Madras, and Karachi. Although the mutinies were rapidly suppressed, they had the effect of spurring the Attlee government to action. Labour Prime Minister Clement Attlee had been deeply interested in Indian independence since the 1920s, and for years had supported it. He now took charge of the government position and gave the issue the highest priority. A Cabinet Mission was sent to India led by the Secretary of State for India, Lord Pethick Lawrence, which also included Sir Stafford Cripps, who had visited India four years before. The objective of the mission was to arrange for an orderly transfer to independence.[58]

In early 1946, new elections were held in India. With the announcement of the polls the line had been drawn for Muslim voters to choose between a united Indian State or Partition.[59] At the end of the war in 1945, the colonial government had announced the public trial of three senior officers of Subhas Chandra Bose's defeated Indian National Army who stood accused of treason. Now as the trials began, the Congress leadership, although it never supported the INA, chose to defend the accused officers.[60] The subsequent convictions of the officers, the public outcry against the beliefs, and the eventual remission of the sentences created positive propaganda for the Congress, which enabled it to win the party's subsequent electoral victories in eight of the eleven provinces.[61] The negotiations between the Congress and the Muslim League, however, stumbled over the issue of partition.

British rule had lost its legitimacy for most Hindus, and conclusive proof of this came in the form of the 1946 elections with the Congress winning 91 percent of the vote among non-Muslim constituencies, thereby gaining a majority in the Central Legislature and forming governments in eight provinces, and becoming the legitimate successor to the British government for most Hindus. If the British intended to stay in India the acquiescence of politically active Indians to British rule would have been in doubt after these election results, although the views of many rural Indians were uncertain even at that point.[62] The Muslim League won the majority of the Muslim vote as well as most reserved Muslim seats in the provincial assemblies, and it also secured all the Muslim seats in the Central Assembly. Recovering from its performance in the 1937 elections, the Muslim League was finally able to make good on the claim that it and Jinnah alone represented India's Muslims[63] and Jinnah quickly interpreted this vote as a popular demand for a separate homeland.[64] However, tensions heightened while the Muslim League was unable to form ministries outside the two provinces of Sind and Bengal, with the Congress forming a ministry in the NWFP and the key Punjab province coming under a coalition ministry of the Congress, Sikhs and Unionists.[65]

The British, while not approving of a separate Muslim homeland, appreciated the simplicity of a single voice to speak on behalf of India's Muslims.[66] Britain had wanted India and its army to remain united to keep India in its system of 'imperial defence'.[67][68] With India's two political parties unable to agree, Britain devised the Cabinet Mission Plan. Through this mission, Britain hoped to preserve the united India which they and the Congress desired, while concurrently securing the essence of Jinnah's demand for a Pakistan through 'groupings. [69] The Cabinet mission scheme encapsulated a federal arrangement consisting of three groups of provinces. Two of these groupings would consist of predominantly Muslim provinces, while the third grouping would be made up of the predominantly Hindu regions. The provinces would be autonomous, but the centre would retain control over the defence, foreign affairs, and communications. Though the proposals did not offer independent Pakistan, the Muslim League accepted the proposals. Even though the unity of India would have been preserved, the Congress leaders, especially Nehru, believed it would leave the Center weak. On 10 July 1946 Nehru gave a "provocative speech," rejected the idea of grouping the provinces and "effectively torpedoed" both the Cabinet mission plan and the prospect of a United India.[70]'

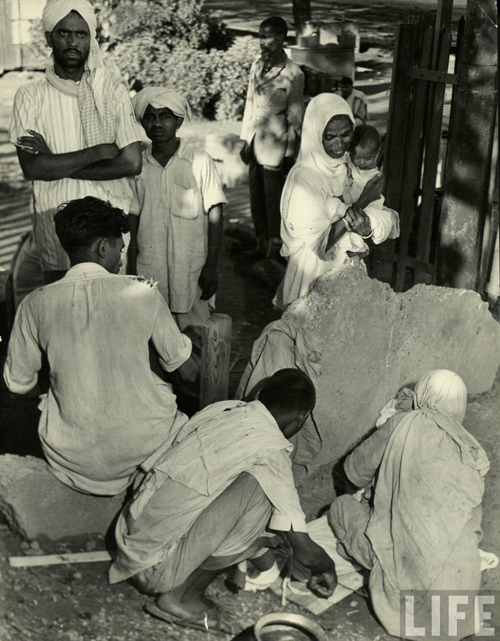

After the Cabinet Mission broke down, Jinnah proclaimed 16 August 1946 Direct Action Day, with the stated goal of peacefully highlighting the demand for a Muslim homeland in British India. However, on the morning of the 16th, armed Muslim gangs gathered at the Ochterlony Monument in Calcutta to hear Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, the League's Chief Minister of Bengal, who, in the words of historian Yasmin Khan, "if he did not explicitly incite violence certainly gave the crowd the impression that they could act with impunity, that neither the police nor the military would be called out and that the ministry would turn a blind eye to any action they unleashed in the city."[71] That very evening, in Calcutta, Hindus were attacked by returning Muslim celebrants, who carried pamphlets distributed earlier which showed a clear connection between violence and the demand for Pakistan, and directly implicated the celebration of Direct Action Day with the outbreak of the cycle of violence that would later be called the "Great Calcutta Killing of August 1946".[72] The next day, Hindus struck back, and the violence continued for three days in which approximately 4,000 people died (according to official accounts), both Hindus and Muslims. Although India had had outbreaks of religious violence between Hindus and Muslims before, the Calcutta killings were the first to display elements of "ethnic cleansing".[73] Violence was not confined to the public sphere, but homes were entered and destroyed, and women and children were attacked.[74] Although the Government of India and the Congress were both shaken by the course of events, in September, a Congress-led interim government was installed, with Jawaharlal Nehru as united India's prime minister.

The communal violence spread to Bihar (where Hindus attacked Muslims), to Noakhali in Bengal (where Muslims targeted Hindus), to Garhmukteshwar in the United Provinces (where Hindus attacked Muslims), and on to Rawalpindi in March 1947 in which Hindus were attacked or driven out by Muslims.[75]

The British Prime Minister Attlee appointed Lord Louis Mountbatten as India's last viceroy, and he was given the task to oversee British India's independence by June 1948, with the instruction to avoid partition and preserve a United India, but with adaptable authority to ensure a British withdrawal with minimal setbacks. Mountbatten hoped to revive the Cabinet Mission scheme for a federal arrangement for India. But despite his initial keenness for preserving the centre, the tense communal situation caused him to conclude that partition had become necessary for a quicker transfer of power.[76][77][78][79]

Vallabhbhai Patel was one of the first Congress leaders to accept the partition of India as a solution to the rising Muslim separatist movement led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah. He had been outraged by Jinnah's Direct Action campaign, which had provoked communal violence across India and by the viceroy's vetoes of his home department's plans to stop the violence on the grounds of constitutionality. Patel severely criticized the viceroy's induction of League ministers into the government and the revalidation of the grouping scheme by the British without Congress approval. Although further outraged at the League's boycott of the assembly and non-acceptance of the plan of 16 May despite entering government, he was also aware that Jinnah enjoyed popular support amongst Muslims, and that an open conflict between him and the nationalists could degenerate into a Hindu-Muslim civil war. The continuation of a divided and weak central government would in Patel's mind, result in the wider fragmentation of India by encouraging more than 600 princely states towards independence.[80] Between the months of December 1946 and January 1947, Patel worked with civil servant V. P. Menon [Rao Bahadur Vappala Pangunni Menon] on the latter's suggestion for a separate dominion of Pakistan created out of Muslim-majority provinces. Communal violence in Bengal and Punjab in January and March 1947 further convinced Patel of the soundness of partition. Patel, a fierce critic of Jinnah's demand that the Hindu-majority areas of Punjab and Bengal be included in a Muslim state, obtained the partition of those provinces, thus blocking any possibility of their inclusion in Pakistan.

The Partition of Bengal in 1947, part of the Partition of India, divided the British Indian province of Bengal based on the Radcliffe Line between India and Pakistan. Predominantly Hindu West Bengal became a state of India, and predominantly Muslim East Bengal (now Bangladesh) became a province of Pakistan....

The partition, with the power transferred to Pakistan and India on 14–15 August 1947, was done according to what has come to be known as the "3 June Plan" or "Mountbatten Plan"....

In 1905, the first partition in Bengal was implemented as an administrative preference, making governing the two provinces, West and East Bengal, easier.[2] While the partition split the province between West Bengal, in which the majority was Hindu, and the East, where the majority was Muslim, the 1905 partition left considerable minorities of Hindus in East Bengal and Muslims in West Bengal. While the Muslims were in favour of the partition, as they would have their own province, Hindus were not. This controversy led to increased violence and protest and finally, in 1911, the two provinces were once again united.....

Under the Mountbatten Plan, a single majority vote in favour of partition by either notionally divided half of the Assembly would have decided the division of the province, and hence the house proceedings on 20 June resulted in the decision to partition Bengal. This set the stage for the creation of West Bengal as a province of India and East Bengal as a province of the Dominion of Pakistan....

After it became apparent that the division of India on the basis of the Two-nation theory would almost certainly result in the partition of the Bengal province along religious lines, Bengal provincial Muslim League leader Suhrawardy came up with a new plan to create an independent Bengal state that would join neither Pakistan nor India and remain unpartitioned. Suhrawardy realised that if Bengal was partitioned, it would be economically disastrous for East Bengal as all coal mines, all jute mills but two and other industrial plants would certainly go to the western part since these were in an overwhelmingly Hindu majority area. Most important of all, Calcutta, then the largest city in India, an industrial and commercial hub and the largest port, would also go to the western part. Suhrawardy floated his idea on 24 April 1947 at a press conference in Delhi.

However, the plan directly ran counter to that of the Muslim League's, which demanded the creation of a separate Muslim homeland on the basis of the two-nation theory. Bengal provincial Muslim League leadership opinion was divided. Barddhaman's League leader Abul Hashim supported it. On the other hand, Nurul Amin and Mohammad Akram Khan opposed it. But Muhammad Ali Jinnah realised the validity of Suhrawardy's argument and gave his tacit support to the plan. After Jinnah's approval, Suhrawardy started gathering support for his plan.

On the Congress side, only a handful of leaders agreed to the plan. Among them was the influential Bengal provincial congress leader Sarat Chandra Bose, the elder brother of Netaji [Subhas Chandra Bose] and Kiran Shankar Roy. However most other BPCC leaders and Congress leadership including Nehru and Patel rejected the plan. The Hindu nationalist party Hindu Mahasabha under the leadership of Shyama Prasad Mukherjee vehemently opposed it. Their opinion was that the plan is nothing but a ploy by Suhrawardy to stop the partition of the state so that the industrially developed western part including the city of Kolkata remains under League control. They also opined that even though the plan asked for a sovereign Bengal state, in practice it will be a virtual Pakistan and the Hindu minority will be at the mercy of the Muslim majority forever....

Soon afterwards, division arose among Bose and Suhrawardy on the question of the nature of the electorate; separate or joint. Suhrawardy insisted upon maintaining the separate electorate for Muslims and Non-Muslims. Bose was opposed to this. He withdrew and due to lack of any other significant support from the Congress's side, the United Bengal plan was discarded....

A massive population transfer began immediately after partition. Millions of Hindus migrated to India from East Bengal. The majority of them settled in West Bengal. A smaller number went to Assam, Tripura and other states. However the refugee crisis was markedly different from Punjab at India's western border. Punjab witnessed widespread communal riots immediately before partition. As a result, population transfer in Punjab happened almost immediately after the partition as terrified people left their homes from both sides. Within a year the population exchange was largely complete between East and West Punjab. But in Bengal, violence was limited only to Kolkata and Noakhali. And hence in Bengal migration occurred in a much more gradual fashion and continued over the next three decades following partition. Although riots were limited in pre-independence Bengal, the environment was nonetheless communally charged. Both Hindus in East Bengal and Muslims in West Bengal felt unsafe and had to take a crucial decision that is whether to leave for an uncertain future in another country or to stay in subjugation under the other community. Among Hindus in East Bengal those who were economically better placed, particularly higher caste Hindus, left first. Government employees were given a chance to swap their posts between India and Pakistan. The educated urban upper and middle class, the rural gentry, traders, businessmen and artisans left for India soon after partition. They often had relatives and other connections in West Bengal and were able to settle with less difficulty. Muslims followed a similar pattern. The urban and educated upper and middle class left for East Bengal first.

However poorer Hindus in East Bengal, most of whom belonged to lower castes like the Namashudras found it much more difficult to migrate. Their only property was immovable land holdings. Many sharecropped. They didn't have any skills other than farming. As a result, most of them decided to stay in East Bengal. However the political climate in Pakistan deteriorated soon after partition and communal violence started to rise. In 1950 severe riots occurred in Barisal and other places in East Pakistan, causing a further exodus of Hindus.... Throughout the next two decades Hindus left East Bengal whenever communal tensions flared up or relationship between India and Pakistan deteriorated, as in 1964. The situation of the Hindu minority in East Bengal reached its worst in the months preceding and during the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971, when the Pakistani army systematically targeted ethnic Bengalis regardless of religious background as part of Operation Searchlight....

Though Muslims in post-independence West Bengal faced some discrimination, it was unlike the state sponsored discrimination faced by the Hindus in East Bengal. While Hindus had to flee from East Bengal, Muslims were able to stay in West Bengal. Over the years, however, the community became ghettoised and was socially and economically segregated from the majority community. Muslims lag well behind other minorities like Sikhs and Christians in almost all social indicators like literacy and per capita income.

-- Partition of Bengal (1947), by Wikipedia

Patel's decisiveness on the partition of Punjab and Bengal had won him many supporters and admirers amongst the Indian public, which had been tired of the League's tactics. Still, he was criticized by Gandhi, Nehru, secular Muslims and socialists for a perceived eagerness for the partition. When Lord Mountbatten formally proposed the plan on 3 June 1947, Patel gave his approval and lobbied Nehru and other Congress leaders to accept the proposal. Knowing Gandhi's deep anguish regarding proposals of partition, Patel engaged him in private meetings discussions over the perceived practical unworkability of any Congress-League coalition, the rising violence, and the threat of civil war. At the All India Congress Committee meeting called to vote on the proposal, Patel said:

I fully appreciate the fears of our brothers from [the Muslim-majority areas]. Nobody likes the division of India, and my heart is heavy. But the choice is between one division and many divisions. We must face facts. We cannot give way to emotionalism and sentimentality. The Working Committee has not acted out of fear. But I am afraid of one thing, that all our toil and hard work of these many years might go waste or prove unfruitful. My nine months in office have completely disillusioned me regarding the supposed merits of the Cabinet Mission Plan. Except for a few honourable exceptions, Muslim officials from the top down to the chaprasis (peons or servants) are working for the League. The communal veto given to the League in the Mission Plan would have blocked India's progress at every stage. Whether we like it or not, de facto Pakistan already exists in the Punjab and Bengal. Under the circumstances, I would prefer a de jure Pakistan, which may make the League more responsible. Freedom is coming. We have 75 to 80 percent of India, which we can make strong with our genius. The League can develop the rest of the country.[81]

Following Gandhi's denial[82] and Congress' approval of the plan, Patel represented India on the Partition Council, where he oversaw the division of public assets and selected the Indian council of ministers with Nehru. However, neither he nor any other Indian leader had foreseen the intense violence and population transfer that would take place with partition. Late in 1946 the Labour government in Britain, its exchequer exhausted by the recently concluded World War II, decided to end British rule of India, and in early 1947 Britain announced its intention of transferring power no later than June 1948. However, with the British army unprepared for the potential for increased violence, the new viceroy, Louis Mountbatten, advanced the date for the transfer of power, allowing less than six months for a mutually agreed plan for independence. In June 1947, the nationalist leaders, including Nehru and Abul Kalam Azad on behalf of the Congress, Jinnah representing the Muslim League, B. R. Ambedkar representing the Untouchable community, and Master Tara Singh representing the Sikhs, agreed to a partition of the country along religious lines in stark opposition to Gandhi's views. The predominantly Hindu and Sikh areas were assigned to the new India and predominantly Muslim areas to the new nation of Pakistan; the plan included a partition of the Muslim-majority provinces of Punjab and Bengal. The communal violence that accompanied the announcement of the Radcliffe Line, the line of partition, was even more horrific. Describing the violence that accompanied the Partition of India, historians Ian Talbot and Gurharpal Singh write:

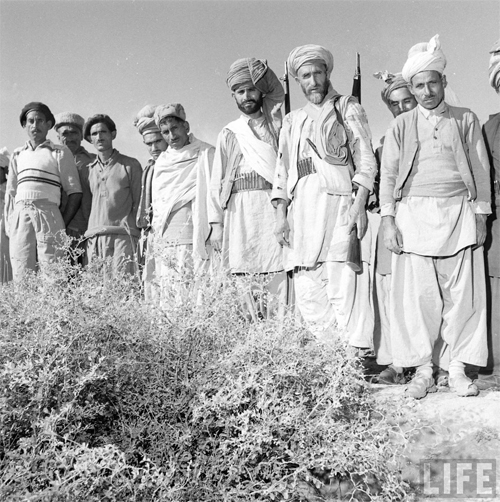

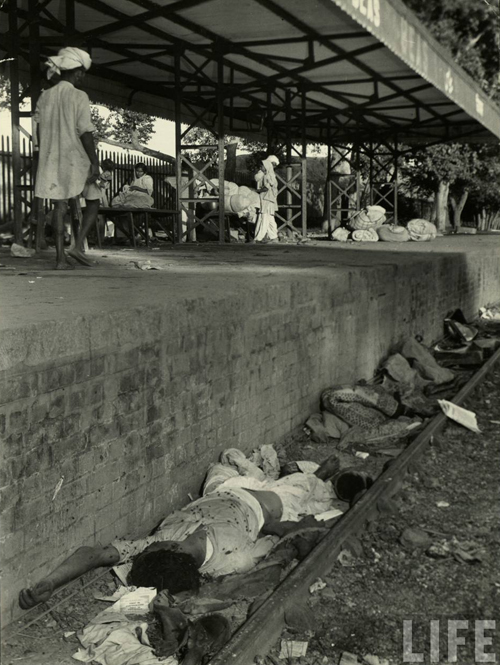

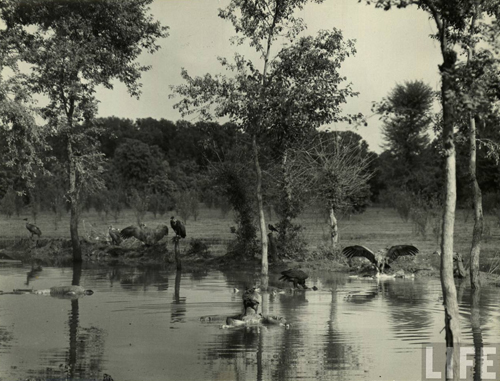

There are numerous eyewitness accounts of the maiming and mutilation of victims. The catalogue of horrors includes the disembowelling of pregnant women, the slamming of babies' heads against brick walls, the cutting off of the victim's limbs and genitalia, and the displaying of heads and corpses. While previous communal riots had been deadly, the scale and level of brutality during the Partition massacres was unprecedented. Although some scholars question the use of the term 'genocide' concerning the Partition massacres, much of the violence was manifested with genocidal tendencies. It was designed to cleanse an existing generation and prevent its future reproduction."[83]

On 14 August 1947, the new Dominion of Pakistan came into being, with Muhammad Ali Jinnah sworn in as its first Governor-General in Karachi. The following day, 15 August 1947, India, now a smaller Union of India, became an independent country with official ceremonies taking place in New Delhi, and with Jawaharlal Nehru assuming the office of prime minister, and the viceroy Mountbatten staying on as its first Governor General. Gandhi remained in Bengal to work with the new refugees from the partitioned subcontinent.

Geographic partition, 1947

Mountbatten Plan

Mountbatten with a countdown calendar to the Transfer of Power in the background

The actual division of British India between the two new dominions was accomplished according to what has come to be known as the "3 June Plan" or "Mountbatten Plan". It was announced at a press conference by Mountbatten on 3 June 1947, when the date of independence - 15 August 1947 - was also announced. The plan's main points were:

• Sikhs, Hindus and Muslims in Punjab and Bengal legislative assemblies would meet and vote for partition. If a simple majority of either group wanted partition, then these provinces would be divided.

• Sind and Baluchistan were to make their own decision.[84]

• The fate of Northwest Frontier Province and Sylhet district of Assam was to be decided by a referendum.

• India would be independent by 15 August 1947.

• The separate independence of Bengal was ruled out.

• A boundary commission to be set up in case of partition.

The Indian political leaders accepted the Plan on 2 June. It could not deal with the question of the princely states, which were not British possessions, but on 3 June Mountbatten advised them against remaining independent and urged them to join one of the two new dominions.[85]

The Muslim League's demands for a separate country were thus conceded. The Congress's position on unity was also taken into account, while making Pakistan as small as possible. Mountbatten's formula was to divide India and, at the same time, retain maximum possible unity.

Abul Kalam Azad expressed concern over the likelihood of violent riots, to which Mountbatten replied:

At least on this question I shall give you complete assurance. I shall see to it that there is no bloodshed and riot. I am a soldier and not a civilian. Once the partition is accepted in principle, I shall issue orders to see that there are no communal disturbances anywhere in the country. If there should be the slightest agitation, I shall adopt the sternest measures to nip the trouble in the bud.[86]

Jagmohan has stated that this and what followed showed a "glaring failure of the government machinery".[86]

[b]On 3 June 1947, the partition plan was accepted by the Congress Working Committee.[87] Boloji states that in Punjab, there were no riots, but there was communal tension, while Gandhi was reportedly isolated by Nehru and Patel and observed maun vrat (day of silence). Mountbatten visited Gandhi and said he hoped that he would not oppose the partition, to which Gandhi wrote the reply: "Have I ever opposed you?"[88]

Within British India, the border between India and Pakistan (the Radcliffe Line) was determined by a British Government-commissioned report prepared under the chairmanship of a London barrister, Sir Cyril Radcliffe. Pakistan came into being with two non-contiguous enclaves, East Pakistan (today Bangladesh) and West Pakistan, separated geographically by India. India was formed out of the majority Hindu regions of British India, and Pakistan from the majority Muslim areas.