by admin » Sat Sep 04, 2021 3:13 am

by admin » Sat Sep 04, 2021 3:13 am

Part 2 of 2

Staircases

At the main gateways, staircases of two stories were usually provided on either side. Usually staircases were also provided at one or both sides of the special rooms (Khanaha-i-Padshah) or the corner bastions such as at Pakka Sarai and Begum-ki-Sarai.

Parapets

Parapets were usually in the form of medium-sized battlements such as in Begum-ki-Sarai or Sarai Rewat. The merions in the case of Rewat give it the appearance of a fortress. But at other places, such as Sarai Kharbuza and Sarai Pakka, the parapets are simple and plain.

Inscriptions

No proper inscription has been found in any of the surviving sarais in Pakistan. Only some scribbling belonging to different periods has been reported from Begum-ki-Sarai at Attock.69 Outside Pakistan, two Persian inscriptions are known from Sarai Ekdilbad, near Etawa, commemorating the simultaneous construction of a mauza (villageltown), a sarai, and a garden by Shah Jahan.70 Sarai Amanat Khan, built in 1640-1641 by Ahmanat Khan himself, the famous calligrapher of the Taj Mahal, also bears a dedicatory inscription on the west gate71 Sarai Nur Mahal near Phillour (East Punjab, India), the most impressive of all sarais in the Punjab built by Empress Nur Jahan, also bears a dedicatory inscription with two dates A.H. 1028 (A.D. 1618) and A.H. 1030 (A.D. 1620).72

Hamams

Turkish hamams of the Roman thermae type were a speciality of the Mughals and were introduced by them into the subcontinent. Their palaces (Lahore Fort), gardens (Shalamar, Lahore, and Wah Gardens at Hasanabdal), and even some of their sarais (Sarai Itamadud Daula at Doraha), were provided with elaborate hamams. It was Jahangir (A.D. 1605-1628) who introduced hamam into sarais. This practice was continued by others. In none of the sarais in Pakistan is such a hamam known to have survived. However, we have a beautiful and colossal public hamam, attached to, though structurally detached from, Sarai Wazir Khan, inside Delhi Gate, Lahore. It has now been renovated. Wah Gardens, a place officially known as Farood Gah-i-Shahinshah-i-Mughalia or the Resting Place of the Mughal Emperors and therefore to be considered as a category of sarai or temporary residence, has an elaborate hamam of which only the foundations have survived.73

Distances

There is some confusion as regards the exact distance between two sarais, baolis, and kos minars of the Mughal period. The difficulty is due to the conversion of a kos or krohlkrosa into English miles. The former appears to have been measured differently at various times. We know from Sarwani that Sher Shah built his sarais at a distance of two kos.74 His son Salim Shah added one more sarai in between every two built by his father. Thus making the distance between two sarais equal to one koso Sarkar, on the other hand, states that Suri sarais were situated 10 kos apart75 whereas sarais of Jahangir's period according to his own decree were 8 kos apart on the road from Agra to Lahore?6 Following this, the East India Company established Dak bungalows on the highways at 10 mile intervals.77 But, on the other hand, we know from Akbar Nama that the distance between Sarai Hasanabdal and Sarai Zainuddin Ali on the way to Attock was 4.25 kroh and 5 mans (app. 5 krohs as usually accepted) which is usually estimated to equal 10.5 English miles.78 Now, the Akbari kroh has been estimated to equal 5,000 ilahi gaz (of 30" length) or 4,250 English yards.79 As the distance between Peshawar and Lahore is about 264 miles, there must have been at least 26 sarais between these two stations, of which 20 can easily be recognized or presumed to have existed.

Attendants

Nicholas Withington (1612-1616) while writing about a sarai between Ajmer and Agra talks about "hostesses to dress our victuals if we please."8o Peter Mundy also talks about female attendants in sarais.81 However, no such reference has ever been made by a native writer. Perhaps they refer to female attendants, who together with their males were appointed to cook food for travelers in these sarais and about whom Khafi Khan has written that all Bhatiaras and Bhatiarnain of India are the descendants of these very cooks (nan-bais).82

Charges

We know that in the early days of the sarais, both accommodation and food were free. During the Mauryan period, there used to be charitable lodging houses under government control wherein free accommodation was granted to heretical travelers and to ascetics and Brahmins, whereas artisans, artists, and traders were required to lodge with their co-professionals in what can be called as guest-houses attached to their places of work.83 During Feroze Shah Tughlaq's reign, travelers were provided with free board and lodging for three days. However, some of the sarais, especially those created out of endowments, tended to become rent-earning establishments. Sarai Wazir Khan, inside Delhi Gate, Lahore was certainly one such example whose income, together with that of the grand hamam nearby, supported Wazir Khan's Mosque.84 We also learn from some early western travelers that the charge per room around 1634 was about 1 to 3 pice and 3 dams per day inclusive of stabling for horses and cooking space.85

Caravanserais Remains

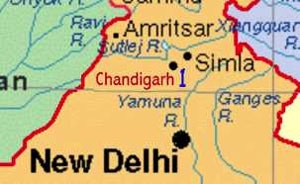

Our knowledge of caravanserais along the Grand Trunk Road between Calcutta and Agra-Oelhi is perfunctory. However, under Mughal rule -- particularly from Jahangir onward-we are not that poor as regards written information and even actual remains, particularly for the part of ancient GTR that stretched from Agra to Lahore and onward to Peshawar. We have an almost perfect alignment of the road from Agra to Lahore as it existed in 1611 and described by William Finch. He lists the following important stations on this section: Agra, Rankata, Bad-ki Sarai, Akbarpur, Hodal, Palwal, Faridabad, Delhi, Narela, Ganaur, Panipat, Karnal, Thanesar, Shahabad, Ambala, Aluwa Sarai, Sirhind, Ooraha (Sarai), Phillaur-kiSarai, Nakodar, Sultanpur, Fatehpur (Vairowal), Hogee Moheed (Taran Taran?), Cancanna Sarai (Khan-i-Sarai), and Lahore.86

Ruins of some interesting sarais are still traceable in that part of the GTR which once passed through Haryana and the East Punjab in India. These include Nur Mahal Sarai near Phillaur built by Empress Nur Jahan; the Sarai at Ghauranda between Panipat and Kamal; Sarai Amanat Khan on the Taran Taran-Attari Road built by Amanat Khan, the calligrapher of the Taj Mahal; Ohakhini Sarai south of the village of Mahlian Kalan on the Nakodar-Kapurthala Road; Ooraha Sarai at Ooraha south of the Ludhiana-Khanna Road; and Sarai Lashkari Khan twelve kilometers west of Khanna on the GTR in the Ludhiana district.87

Sarai Amanat Khan is probably the last existing stretch of the GTR, before the latter enters into present-day Pakistan via Burj and Raja Tall in India to Purani Bhaini in Pakistan and then straight to Manhala Khan-i-Khanan after the name of Abdul Rahim Khan-i-Khan, the famous general of Akbar and Jahangir. Our journey along the GTR in Pakistan begins here. Here once stood the Sarai Khan-i-Khan, most probably the Cancanna Sarai already mentioned by William Finch. This sarai is no more. But, outside the village, a Mughal period kos minar, one of a pair in the locality, still provides positive evidence of the ancient GTR. One of the two kos minars at Manhala has recently disappeared. The other is also not safe as it has a big hole whereby it could collapse without the slightest malevolent human interference.

From Manhala of Khan-i-Khana, the road used to go to Brahmanabad where an interesting baoli with a small pavilion is now in very poor state and will soon be filled in if no remedial action is taken. From here, the road goes to Mahfuzpura Cantonment where an elegant baoli with a double-ringed well and an imposing two-story domed pavilion has given the site its present name of Baoli Camp. It has been recently repaired by army personnel. Then the road goes to Shahu Garhi where the best-preserved kos minar near the railway line is being encroached upon by modern dwellings. Shahu Garhi is only a few minutes away from Chowk Dara Shikoh and then to the Delhi Gate for entry into the Walled City of Lahore. Here just beside the gate was Sarai Wazir Khan next to a grand public hamam also built by Wazir Khan.

Retracing our steps to mainland India, from Sarai Amanat Khan there was a shorter route which bypassed Lahore and directly reached Eminabad passing through Amritsar in India and Pull Shah Daula in Pakistan. At the latter site we have one of the best-preserved of all Mughal period bridges. This bridge was built on Nala Dek by the famous saint, Shah Jahan. We shall come back to this bridge later.

The Walled City of Lahore marked the starting point of three routes: the road to Delhi and Agra from Delhi Gate on the eastern side, the road to Multan to the south side from the Lahori Gate, and the road to Peshawar from the north side through the Khizri or Kashmiri Gate.

The ancient route to Multan has not so far been studied properly. A hurried survey by the author brought to light a number of remains of ancient sarai along this road, one each at Sarai Chheamba, Sarai Mughal, Sarai Harappa, Sarai Siddhu, and Sarai Khatti Chaur-the last named sarai is different from the rabat at the same site as mentioned above. The Mughal-period sarai at this site was partially excavated by the author during the conservation of the Mughal-period mosque which is probably part of the sarai.

The present study is confined to the GTR going towards the north. For this purpose, the ferry passage over the River Ravi was from the Khizri Gate over to Shahdara-the King's way to Lahore. The precise course of the ancient GTR between Shahdara and Gujranwala is not clear at all points, but it was certainly a little north of the present course. At Shahdara, we have the best-preserved sarais in all Pakistan. Originally built during the Suri period as its mosque still testifies, the present edifice with its three magnificent gateways dates back to Shah Jahan's period. As it was sandwiched between two great monuments -- the Mausoleum-garden ofJahangir and the Mausoleum-garden of Asif Khan -- it served both and hence was saved for posterity.

From Shahdara, the road moves northward passing through Rana Town where, until they were both filled in in 1987, there were two baolis next to the present GTR. From Rana Town, it takes a turn to cross Nullah Deg at Bahmanwali/Chak 46. The crossing is still marked by an ancient bridge and the ruins of a sarai nearby. From here it went straight to Sarai Shaikhan (also called Pukhta Sarai), where a magnificent paneled gateway and an ancient well stand in ruinous condition. From Sarai Shaikhan the road goes to Tapiala Dost Muhammad via Kot Bashir (Chhaoni site and a baoli) to Dera Kharaba (baoli), Tapiala Dost Muhammad (mausoleum) for the onward journey to Pull Shah Daula with an ancient bridge on Nallah Deg, and monuments at Baba Jamna. It continues on to Gunaur, Wahndoki (ancient mound), and Eminabad, where a number of monuments-ancient bridge, baoli, mosque, and tank-give the area some sanctity. Finally, it reaches Kachi Sarai at Gujranwala.88 This sarai, built of mud brick in the characteristic Suri fashion, was intact until about half a century ago. Today, it has totally vanished, leaving behind its central mosque. The baoli of the sarai has also been filled in. The huge vacant area nearby for army encampments (parao) has also been covered with modern constructions. From Eminabad to Gujranwala, I examined a few baolis and a portion of the ancient GTR, with brick-paved berms during my survey in 1987. From Gujranwala, it passes through Gakkhar Gheema, Dhaunkal (baoli, ancient mosque), and Wazirbad (dak-chowki), crosses Nullah Palkhow and the River Chenab, and reaches Gujrat. The dak-chowki at Wazirbad has recently been repaired by the author, but the Akbar-period fort and baoli and a public hamam inside the fort at Gujrat, are seriously threatened. Gujrat was an important station on the ancient GTR as it is on the present-day national highway. From here emanate four roads to Kashmir via Bhimber (where there is a sarai still today), to Lahore via Eminbad just described, and to Lahore by a loop road via Shaikhupura (with a hunting ground at Hiran Minar and an elegant baoli at Jandiala Sher Khan), Hafizabad, and then to Rasul Nagar. The fourth road goes to Peshawar via Khawaspura on Bhimber Nullah, passes through a village called Baoli Sharif (baoli), Kharian with two baolis, a British-period sarai (now partially filled in), on to Sarai Alamgir (sarai and mosque), and crosses the Jhelum River to reach Jhelum city with the Mangla Fort some miles north of it. From here the ancient road deviates a little to the south and goes to the Rohtas Fort with two baolis and an ancient mosque within the fort. Sarai Sultan with a small baoli on the opposite bank of the River Kahan is fully occupied by a modern village -- its main gate and the baoli are also endangered. Midway between Sarai Sultan and Domeli still stand the remains of a huge baoli but without a pavilion -- it is called Khoji baoli.

From Sarai Sultan to Sar Jalal or Jalal Khurd, the path of the ancient road is not clear. It certainly passed through Khojki (baoli) and Domeli where there are hot water springs and another baoli (reported) nearby. But where did the ancient road cross the hot water springs mountain? We are not sure. In historical accounts, at least four stations have been mentioned, namely Rohtas Khurd, Saeed Khan, Naurangabad, and Chokuha between Rohtas and Jalal Khurd. Rohtas Khurd may correspond to Sultan Sarai, but identification of the others remains uncertain. At Jalal Khurd (modern Sar Jalal) we come across the ruins of a sarai (?), an ancient pakka tank, and a T ughlaq-period mosque. From here, the ancient road led to Rewat passing on the way through Dhamyak (grave of Sultan Muhammad Ghori), Hattiya, Mahsa, and Pakka Sarai off Gujar Khan. The Pakka Sarai has survived on the high bank of a hilly torrent.89 It has a well and two mosques inside it and a small baoli outside. At Kallar Sayyidan too, two bao/is have been reported. From here the road reaches Rewat Fort which actually marks the site of a preMughal Sarai with a grand mosque inside it. At Rewat, the modern GTR joins up with the ancient road again.

The course of the ancient road from Rewat to Sarai Kharbuza, once again, is not clear. We once had two square stone bao/is within the fork of the Islamabad-Rawalpindi Road near Rewat, now filled in, and that is all. There are usually two stations in European accounts, namely Lashkari and Rawalpindi. The ancient road probably bypassed presentday Rawalpindi to the north and went straight first to the Pharwala fort and then across the Soan River to Golra Sharif. Two kos minars once stood near Golra railway station. These are still on the record of the Department of Archaeology as protected monuments but are there no more. Onward at Sarai Kharbuza near Tarnol and Sangjani we meet the remains of a saraiwith a baoli and mosque inside it.90 From Sarai Kharbuza, an off-shoot of the GTR went north through Shah Allah Ditta over the mountain to Kainthala for the onward journey to Dhamtaur near Abbotabad as a short cut to Kashmir. At Kainthala we still have a baoli with fresh drinking water and the remains of an ancient road and an ancient site called Rajdhani, a seat of government.

From Sarai Kharbuza, the main GTR goes to Margala Pass where the modern GTR meets it and Attock. At the Margala Pass and under the shadow of the towering Nicholson monument, we still have a considerable stretch of stone-paved road with a Persian inscription from the period of the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb Alamgir (1658-1705). The stone slab has now been removed and preserved in the Lahore Fort. The historic Giri Fort is not far from the Margalla Pass. From Margalla, the modern GTR joins the ancient one at least as far as Hasanabdal. On the way there are the dilapidated remains of a sarai at Sarai Kala of which only the gateway and mosque remain. At Sarai Kala we meet the remains of an ancient bridge on Kalapani. From this bridge onward, the alignment of the ancient road is marked by the magnificent Laoser Baoli within the Wah Cantonment, the remains of the beautiful Wah Gardens with a Farood Gah-i-Shahinshah-i-Mughalia -- that is to say, the Resting Place of the Mughal Emperors built by Jahangir (1605-1628)-and then another square sarai at Hasanabdal with a sacred tank and two mausoleums. From Hasanabdal onward the road goes to Burhan where once stood to be Sarai Zainud Din Ali (not yet located), to Hattian (Saidan Baoli), to Kamra (Chitti Baoli), Behram Baradari (small walled garden), Begum-ki-Sarai (sarai, mosque, and a square kos minar), and finally Attock where there is still an impressive fort from the Akbar period (1556-1605) with a Persian inscription and an ancient well, a baoli on the bank of Dakhnir Nullah south of Rumain, and the pillars of a boat-bridge from the Akbar period on the Indus River.

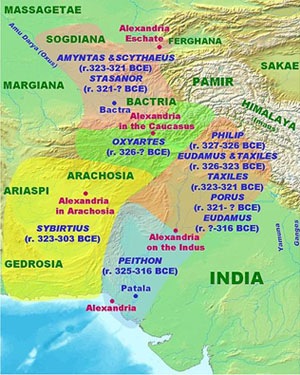

Beyond Attock, the ancient road probably used to run northward as does the modern GTR, although the path of the ancient GTR between Attock and Peshawar is not very clear. Very few historical landmarks have so far been recorded between these two historic cities. I know of only one ancient stepped well or baoli just beside the modern GTR near Aza Khe! Payan (Pir Payai railway station), between Nowsherhra and Peshawar. Khushhal Khan Khattack's garden-pavilion at Vallai near Akora Khattack was also probably not far from the path of the ancient GTR. Otherwise, a few more baolis have recently been located between Peshawar and Attock by a team from Peshawar University but they are mostly modern. No report has so far been published. The only definite landmark in this region is the famous Sarai Jahan Aura Begum at Peshawar built by Princess Jahan Aura, daughter of Shah Jahan (1627- 1658), who after the death of her mother became the First Lady of the Empire. Her sarai is popularly known as Gop Khatri as it was built on top of an ancient site of the same name which dated from the second century B.C. The gateway to this sarai is currently being repaired. Very few original cells have been preserved. Qila Bala Hisar in the same city also provides a landmark and fixes a point on the GTR for the onward journey to Kabul. Beyond that point, there are only three more landmarks: Jamrud (Fort), Ali Masjid (famous for its Buddhist Stupa), and Landikotal (Shapoola Stupa). Whether there are remains of any sarai, baoli, kos minar, or dak-chowki between Peshawar and Jalalabad, I am not sure. No published information is available, but the author is hopeful that a survey may reveal some interesting information.

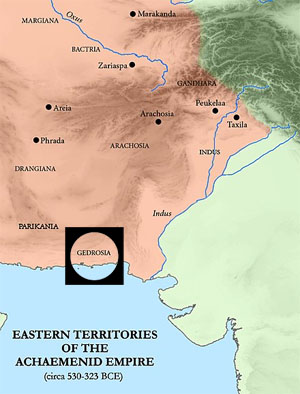

This section is a brief account of the ancient course of the Grand Trunk Road (and its halting stations) which has marked the history of the whole of Northern India as it is today. Along this road marched not only the mighty armies of conquerors, but also the caravans of traders, scholars, artists, and common folk. Together with people, moved ideas, languages, customs, and cultures, not just in one, but in both directions. At different meeting places -- permanent as well as temporary -- people of different origins and from different cultural backgrounds, professing different faiths and creeds, eating different food, wearing different clothes, and speaking different languages and dialects would meet one another peacefully. They would understand one another's food, dress, manners and etiquette, and even borrow words, phrases, idioms and, at times, whole languages from others. As a result of this exchange of people and ideas along this ancient road and in its caravanserais, beside the cooling waters of the stepped wells and in the cool shade of their pavilions, waiting at the crossroads and under the shadows of the mighty kos minars, the seeds of new ways of life, new cultures, and new peoples took root. This was the role of this mighty highway that connected Central Asia with the subcontinent of Pakistan and India. The devastation wrought by invading armies has been forgotten. Merchandise bought and sold has been lost. But the seeds of cultural exchange sown along this road have taken root and given shape to new cultural phenomena that have determined the course of life today along these routes. Here lies the value of the ancient Grand Trunk Road and the halting stations on it.

_______________

Notes:

1. K.M. Sarkar, The Grand Trunk Road in the Punjab: 1849-1886 (Lahore: Punjab Government Record Office Publications, 1926), p. 8, (Monograph No. I).

2. John Wiles, The Grand Trunk Road in the Punjab: Kyber to Calcutta (London: 1972), pp. 7-16. Rudyard Kipling, as quoted by Wiles (p. 8), described this road as a mighty way "bearing, without crowding India's traffic for 1,500 miles such a River of life as nowhere else exists in the world. "

3. Sir James Douie, North West Frontier Province, Punjab and Kashimir, p. 126, see Sarkar, Grand Trunk Road, p. 7.

4. H.L.O. Garret in Sarkar, Grand Trunk Road, Prefatory Note.

5. John Wiles, Grand Trunk Road, p. 7.

6. The part of the Silk Road which passed through Pakistan corresponds to the Grand Trunk Road from Peshawar to Lahore. However, at Lahore, instead of going straight to Delhi, it bent southward and, while embracing the present-day National Highway, it used to terminate at Barbaricon near Karachi and joined the Sea Route. Alexander the Great also followed the same road up to the River Beas. Later invaders, almost without exception, followed the same road to reach the coveted throne of Delhi.

7. Sarkar, Grand Trunk Road, pp. 7-8.

8. See Preface by VS. Agrawala in Moti Chandra, Trade and Routes in Ancient India (New Delhi, 1977), p. vi.

9. Ibid., p. 78; Also see R.P. Kangle, The Kantiliya's Arthasastra, reprinted with Urdu translation by Shan-ul-Haq Haqqi, and Muqadama by Muhammad Ismail (Zabeeh Karachi, 1991), bk. 4, sec. 116, pp. 17-26 (Hamavata Path), and bk. 2. See 22.31 for width of roads.

10. Kangle, Kantiliya's Arthasastra, bk. 2, sec. 19.19 and 38.

11. Ibid., sec. 22, pp. 1-3. Asthaniya was located at the center of800 villages, whereas a dronamukha was at the center of 400 villages (sec. 19.

12. It was on account of and along this Royal Road that Megasthenes could travel to lands never before beheld by Greek eyes. It was maintained by a Board of Works (See Megasthenes' Indika, Fragments 3, 4 and 34, in J.W McCrindle, Ancient India as described by Megasthenes and Arrian (London, 1877), pp. 50, 86. XV I. II. According to Megasthenes, this Royal Road was measured by scheoni (1 scheonus = 40 stadia = one Indian yojana = 4 krosas or kos) and its total length was 10,000 stadia, i.e., about 1,000 koso He also states that there was an authoritative register of the stages on the Royal Road from which Erastothenes derived his estimates of distances between various places in India.

13. Sarkar, Grand Trunk Road, p. 2.

14. Megasthenes' Indika. Ten stadia are usually regarded as equal to 2,022.5 yards or one kos of 4,000 haths--according to some, 8,000 haths. These pillars were meant to show the by-roads and distances. There is great difference of opinion as to what the correct measure of one kos or krosa is-some regard it as less than 3 miles while others regard it as equal to 1.75 miles (2.8 kilometers). Traditionally and within our own memory, a koswas about 2.5 English miles (4 kilometers). For details see Radha Kumud Mookerjee Asoka, 3d ed. (Delhi, 1962), p. 188 wherein he regards 8 kosas equal to 14 miles i.e., I kos = 1.75 miles. Also see Moti Chandra, Trade and Trade Routes in Ancient India (New Delhi, 1977), p. 78.

15. Kangle, The Kautiliya Arthashastra, bk. 2, sec. 56.5.

16. "On the high roads, too, banyan trees were caused to be planted by me that they might give shade to cattle and men, mango-gardens (amba-vadikya) were caused to be planted and wells to be dug by me, at each half kos (adhakosikyam) nimisdhaya were caused to be built, many watering stations (aparani) were caused to be established by me, here and there, for the comfort of cattle and men." See the Seven Pillar Edicts, part 7, as on Dehli-Topra Pillar in Radha Kumud Mookerji, Asoka, pp. 186-93. Also see Dr. R. Bhandarkar, Asoka, 2d ed. (Calcutta, 1932), p. 353.

17. "Nimisdhaya" (Skt. nisdya) has often been translated as "rest-house." Luder, however, translates it as "Steps down to water." Hultzseh also follows Luder. But Woolner and some others do not accept this meaning and are probably right. See also discussion on this word in E. Hultzseh, Corpus Inscription Indicarum, vol. I.

18. Sarkar, Grand Trunk Road, p. 2.

19. Mookerji, Asoka, p. 189, note 3.

20. Moti Chandra, Trade, p. ix. He talks about wells and trees but not the "rest houses" built by Asoka, p. 79. He probably agrees with Luder as regards the meaning of "nimisdhaya" as "stepped well," i.e., baoli.

21. V.S. Agrawala, suggests that, as Kangs were the originators of a canal system in Central Asia in the seventh centuty B.C., Sakas (Scythians) from the same region introduced stepped wells or baolis in the second century B. C.

22. B. Rowland, Art in Ajghanistan. Objects from the Kabul Museum (London: Allen Lane the Penguin Press, 1971), p. 21.

23. Moti Chandra, Trade, p. 19.

24. Saifur Rahman Dar, "The Silk Road and Buddhism in Pakistani Contexts," Lahore Museum Bulletin, vol. I, no. 2 (July-December 1988): pp. 29-53.

25. Moti Chandra, Trade, p. 84. The silence of these travelers about these facilities can be easily explained. As devout Buddhists, they always preferred to stay in Buddhist monasteries which were numerous in those days. Their doors were always open to travelers-pious and lay alike.

26. Muhammad Qasim Farishta, Tarikh-i-Farishta, trans. Abdul Hayee Khawaja (Lahore, 1974), pan I, p. 136. See also MaulanaAbdul Salam Nadvi, Rafo-i-Ama ke kam, Darul Musanafeen, series no. 93 (Azim Garh: n.a.), p. 40. In Briggs' translation of Farishta's history, however, there is no mention of a sarai on the DelhiDaulatabad toad or elsewhere. Instead, Muhammad Tughlaq is reported to have planted shady trees in rows along this road to provide travelers with shade, while poor travelers were fed on this road at public expense. He is also said to have established hospitals for the sick and almshouses for widows and orphans; see Muhammad Qasim Farishta, History of the Rise of the Mahomedan Power in India till the Year 1612, English translation by John Briggs, 4 volumes (1829; reprint Delhi: Low Price Publications, 1990), vol. I, pp. 236 and 242.

27. Shams Siraj Afeef, Tarikh-i-Feroze Shahi, Urdu trans. by Maulvi Muhammad Fida Ali Talib (Karachi: Nafees Academy, 1%5), p. 23. See also R. Nath, History of Sultanate Architecture (New Delhi: Abhinav Publications, 1978), p. 59. From Muhammad Qasim Farishta we learn that Firoze Tughlaq not only repaired the caravanserais built by his predecessors but also built 100 sarais of his own; see Muhammad Qasim Farishta, History of the Rise of the Mohamedan Power in India, vol. 1, pp. 267-70. He also built several other public amenities such as dams, bridges, reservoirs, public wells, public baths and monumental pillars. He set aside lands for the maintenance of these public buildings.

28. Abdul Salam Nadvi, Rafi-i-Ama ke kam, p. 40 quotes Mirat-i-Sikandari, p. 75, for this information.

29. Nadvi, Rafo-i-Ama ke kam, p. 40. Also Qasim Farishta, History of the Rise of the Mohamedan Power in India, vol. 1, p. 186.

30. Abbas Khan Serwani, "Tarikh-i-Sher Shah" in History of India as told by its Historians, edited by H.M. Elliot and John Dowson, vol. 4 (London, 1872), pp. 417-18. See also Rizqullah Mushtaki, Waqiat-i-Mushtaki, in the same volume; Zulfiqar Ali Khan, Sher Shah Suri: Emperor of India (Lahore, 1925); and Hashim Ali Khan (alias Khaft Khan), Mutakhabut-Tawarikh, Urdu translation by Muhmud Ahmad Faruqui, vol. 1 (Karachi: Nafees Academy, 1963), pp. 127-28. The more important roads include the Grand Trunk Road from Sonargaon to the Nilab (Indus River) and those from Lahore to Multan via Harappa and from Agra to Mandu. On the Multan-Lahore Road, there still exist two sarais, namely Sarai Chheemba close to Bhai Pheru (Phul Nagar) and Sarai Mughal near Baloki Headworks. Another Pakka Sarai attributed to Sher Shah Suti was standing as late as 1964, almost in front of the present-day Harappa Museum. A considerable length of an ancient road, still shaded by old trees and called Safon Wali Sarrak, extends on either side of this sarai. This sarai has now been excavated and reported briefly. See Richard H. Meadow and Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, Harappa, 1994-95: Reprints of Reports of the Harappa Archaeological Research Project (December 1995), sec.: "Harappa Excavation 1994," p. 13, fig. 13. Though usually these sarais are attributed to Sher Shah Suri, on the authority of the author of Miasrul Umara, we learn that Khan Dautan Nusrat Jang and Qaleej Khan Torani built several sarais on the road from Lahore to Multan (see note 40 below). Another road linked Lahore with Khushab and onward to the Kurram Valley on the way to Afghanistan. Two beautiful baolis or stepped wells still exist on this road, one each at Gunjial near Quaid Abad and Van Bachran near Mianwali; both are attributed to Sher Shah Suri. See Saifur Rahman Dar, "Khushab-Monuments and Antiquities," Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan, vol. 15, no. 3, part 2 (Lahore, August 1978). There are three interesting baolis in the picturesque Son Valley marking some ancient routes linking Khushab with the Salt Range.

31. Shaikh Rizqullah Mushtaki, "Wakiat-i-Mushtaki," in Elliot and Dowson, History of India, vol. 4, appendix G, p. 550.

32. Elliot and Dowson, History of India, p. 417, footnote 2. This figure occurs in one of the manuscripts of Serwani, whereas Sher Shah is reported as having constructed 2,500 rather than 1,700 sarais. This they attribute to ignorance on two fronts, namely that the total distance between Bengal and the Indus is 2,500 kos, and there was a sarai at each instead of every second koso This tradition can be considered as partly true if it refers to the reign of Salim Shah Suri (A.D. 1545-1552), who is said to have added one more sarai between every two sarais built by his father. Shaikh Rizqullah Mushtaki, "Wakiat-i-Mushtaki," appendix G, p. 550, also puts Suri sarais after one rather than two koso See also Farishta, Tarikh-i-Farishta, vol. I, p. 228, as quoted by Maulana Abdul Salam Nadvi, Rafo-i-Ama ke kam, p. 41.

33. Nadvi, Rafo-i-Ama ke kam, p. 41. Also Qasim Farishta, Tarikh-i-Farishta, vol. 1, p. 332; and Khaft Khan, Muntakhab-ul-Lubab, translated by Muhammad Ahmad Faruqi (Karachi: Nafees Academy, 1963), part 1, p. 135.

34. Dr. M.A. Chaghatai, Tarikhi Masajid-i-Lahore (Lahore, 1976), pp. 29-31.

35. Abul Fazl, Ain-i-Akhbari, vol. 1, p. 115. Among such philanthropists were the widow of Shaikh Abdul Rahim Lukhnavi and Sadiq Muhammad Khan Harvi, who built sarais at Lukhnau and Dhaulpur respectively.

36. The Tuzk-i-Jahangiri or Memoirs of Jahangir, translated by Alexander Rogers, edited by Henry Beveridge (Lahore: Sang-e-Meel Publications, 1974), vol. 1, pp. 7-8, 75, and vol. 2, pp. 63-64, 98, 103, 220, 249; see also Sarkar, Grand Trunk Road, p. 49.

37. Sarkar, Grand Trunk Road, p. 43. Also see Tuzk-i-Jahangiri (Lahore: Nawal Kishore Press, n.d.), p. 5. Such courtiers include Halal Khan, Khawajasara, Saeed Khan Chagatta, the Subedar of Punjab, Shaikh Farid Murtaza Khan Bokhari, and Arnir Ullah Vardi Khan. See Samsamud Daula Shahnawaz Khan, Ma'asrul Umara, Urdu translation by Muhammad Ayub Qadri (Lahore: Urdu Markzi Board, 1%8), pp. 205,407,408,639 under names quoted here: vol. I, p. 205 (Amir Ullah); p. 407 (Halal Khan); vol. 2, p. 408 (Saeed Khan Chagatta); and p. 639 (Farid Murtaza Khan Bukhari). Sarais were built along the roadside whereas rabats were located inside the cities.

38. Rogers and Beveridge, Tuzk-i-jahangiri, p. 77 (Azim Khan). Beside sarais, Jahangir also ordered the preparation of bulghur-khana (free eating houses) where cooked food was served both ro the poor residents as well as travelers; see also A. Rogers and H. Beveridge, Tuzk-i-Jahangiri, vol. 1, p. 75.

39. Ibid, p. 406 and Khafi Khan, Muntakhab-ul-Lubab, p. 302. Jahangir also mentions the existence of several other sarais in his empire, mostly in the Punjab such as Sarai Qazi Ali near Sultanpur, Sarai Pakka near Rewat, Sarai Kharbuza near Tarnaul (also marked on Elphinston's map), Sarai Bara, Sarai Halalabad, Sarai Nur (Mahal) near Sirhind, Sarai Alwatur or Aluwa, and a grand baoli built by his mother at a cost of Rs. 20,000 at Barah. See Rogers and Beveridge, Tuzk-i-Jahangir, vol. 1, pp. 63, 98, and vol. 2, pp. 64, 103, 219, 220,2 49.

40. For example, Azim Khan built a sarai in Islamabad (Mathura) whereas Khan Dauran Nusrat Jang and Qaleeg Khan Torani built sarais every 10 kos on the road from Suraj to Burhanpur and several sarais on the road from Lahore to Multan respectively. See Kahn, Ma'asrul Umara, vol. I, p. 179 (Azim Khan), p. 758. See too previous note.

41. Tariq Masud, "Pull Shah Daula," Lahore Museum Bulletin, vol. 3, no. 2 (July-December 1990).

42. Nadvi, Rafa-i-Ama ke kam, p. 44

43. Shaista Khan, the Emir Umara of Aurangzeb, also built several rabats, mosques and bridges (Ma'asrul Umara, vol. 2, p. 705).

44. Nadvi, Rafa-i-Ama ke kam, p. 44.

45. Kahn, Ma'asrul Umara, vol. 1, p. 358.

46. Kahn, Ma'asrul Umara, vol. 3, p. 882. Also see Nadvi, Rafa-i-Ama ke kam, p. 45.

47. Kahn, Ma'asrul Umara, vol. 1, p. 358, and Nadvi, Rafa-i-Ama ke kam, pp. 44-45.

48. Sarkar, Grand Trunk Road, p. vii.

49. William Foster, ed., Early Travels in India, 1583-1619 (London, 1921; Lahore, 1978), pp. 167-68.

50. Sarkar, Grand Trunk Road, chap. 3-4, pp. 13-45.

51. Moti Chandra, Trade, p. 81, and Abul Fazl, Ain-i-Akbari, vol. 1 (Nawal Kishore Edition), p. 197 (under Ain-i-Kotwal).

52. Shaikh Rizqullah Mushtaki, "Wakiat-i-Mushtaki," in Elliot and Dowson, History of India, vol. 4, appendix G, p. 550; Ishwari Prasad, The Life and Times of Humayun (Bombay: Oriental Longmans, 1955), pp. 168-69; and Dr. Hussain Khan, Sher Shah Suri (Lahore: Ferozsons Ltd., 1987), pp. 332-40. Also see note 32 above.

53. Dr. Hussain Khan, Sher Shah Suri, p. 333.

54. Arthur Upham Pope, Persian Architecture: The Triumph of Form and Colour (New York: George Braziller, 1965), p. 238.

55. Khan, Ma'asrul Umara, vol. 2, p. 639 (see Farid Murtaza Khan Bukhari).

56. Nadvi, Rafa-i-Ama ke kam, p. 45.

57. Dr. Hussain Khan, Sher Shah Suri, p. 333.

58. Ebba Koch, Mughal Architecture: An Outline of Its History and Development (1576- 1858) (Munich: Prestel-Verlag, 1991), p. 67, fig. 65.

59. Catherine B. Asher, "Architecture of Mughal India," in The New Cambridge History of India, vol. 14 (Cambridge, 1992), p. 225.

60. Rogers and Beveridge, Tuzk-i-Jahangiri, vol. 2, p. 182.

61. Subash Parihar, "Two Little-known Mughal Monuments at Fatehbad in East Punjab," Journal of Research Society of Pakistan, vol. 38, no. 2 (Lahore) (April 1991): pp. 57- 62.

62. Subash Parihar, "The Mughal Sarai at Doraha-Architectural Study," East and West, vol. 37 (Rome, December 1987): pp. 309-25.

63. Nur Ahmad Chishti, Tehqiqat-i-Chishti (Lahore: Al-Faisal Printers, 1993), pp. 764-66.

64. Arthur Upham Pope, Persian Architecture, p. 238.

65. Ebba Koch, Mughal Architecture, p. 238.

66. Indian Archaeology, 1980-81, A review (1983): p. 67.

67. There is some controversy as regards the vaulted roof structure in the courtyard of Begum-ki-Sarai. For some it is a mosque, while for others it is not. On either side of the double row of chambers, there are two open platforms, both accessible from within the chamber. Thus, in the western wall, there are three openings in place of a mehrab. This has led some to believe that this structure is a baradari or pavilion rather than a mosque. See Lt. Col. K.A. Rashid, "An Old Serai Near Arrock Fort," reprinted from Pakistan Quarterly, vol. 12, no. 3 (Summer 1964): Plate 4. Bur this is certainly not true. In such deserted places, such as at Begum-ki-Sarai, a mosque was a must. The platform to the west of the Prayer Chamber and three openings in the western walls appear to have been a British-period innovation. Misuse of mosques by British residents for some mundane purpose is not an unknown phenomenon. The use of the famous Dai Anga Mosque, Lahore, as a residence by Mr. Henry Cope, and use of the verandahs of the Badshahi Mosque, Lahore, as a residence for British soldiers, are well-known examples.

68. Lt. Col. K.A. Rashid, "The Inscriptions of Begum Sarai (Arrock)," Journal of Research Society of Pakistan, vol. 1 (Lahore, October 1964): pp. 15-24.

69. Epigraphica India (1953 and 1954), pp. 44-45.

70. Wayne E. Begley, "Four Mughal Caravanserais Built During the Reigns of Jahangir and Shah Jahan," Muqarnas, vol. 1 (1983): p. 173.

71. Subash Parihar, Mughal Monuments in the Punjab and Haryana (New Delhi: Inter-India Publications, 1985), p. 19.

72. Bahadur Khan, "Mughal Garden Wah," Journal of Central Asia, vol. 11, no. 2 (December 1988): p. 154, illust. p. 158.

73. "Tarikh-i-Sher Shah," in Elliot and Dowson, The History of India, p. 140.

74. Sarkar, Grand Trunk Road, p. 48-49.

75. Memoirs of Emperor Jahangir, trans. by Major David Price (Delhi, n.d.), p. 157.

76. Subash Parihar, Mughal Monuments, p. 19 and Sarkar, Grand Trunk Road, p. 48-49.

77. Akbar Nama, vol. 3, p. 378, as quoted by Manzul Haque Siddiqui, Tarikh-i-Hasan Abdal (Lahore), pp. 64-65.

78. Manzar-ul-Haque Siddiqui, Tarikhai-i-Hasan Abdal, p. 65.

79. William Foster, ed., Early Travels, p. 255 and footnote.

80. R.C. Temple, ed., The Travels of Peter Mundy, vol. 2 (London: Hakluyt Society, 1914), p. 121; as quoted by William Foster, Early Travels, p. 225 (footnote).

81. Hussain Khan, Sher Shah Suri, p. 33, and Khafi Khan, Muntakhab-ul-Lubab, vol. I, p.127.

82. R.P. Kangle, Kautiliya Arthashatra, bk. 2. sec. 56, paras. 5-6.

83. Catherine B. Asher, Architecture of Mughal India, p. 225.

84. Foster, Early Travels, p. 225, and Temple, ed., The Travels of Peter Mundy, vol. 2.

85. Foster, Early Travels, pp. 155-60, and Subash Parihar, Mughal Monuments, pp. 19- 26 (footnote 16).

86. Subash Parihar, Mughal Monuments, pp. 19-26. Hugel clearly refers to the road Filor-Nakodar-Sooltanpur-Fatehbad-Noorooddeen Suraee (near Taran Taran), Khyroodden Suraee (near Rajah Ku) -- Manihala-Taihar (baoli nearby) -- Lahore as the "old Badshahee Road." See Baron Charles Hugel, Travels in Kashmir and the Punjab (1845; reprint Lahore: Qausain, 1976), Pocket Map.

87. Waheed Quraishi, "Gujranwala: Past and Present," Oriental College Magazine (Lahore, February-May 1958), p. 20. The first to mention this sarai in 1608 was William Finch under the name "Coojes Sarai." Present-day Gujranwala city actually encompasses the sites of the three ancient sarais and a settlement namely Sarai Kacha, Sarai Kamboh, Sarai Gujran, and a village called Thatta; see Waheed Quraishi, p. 21.

88. In 1607, Jahangir visited this sarai and described the site as "strangely full of dust and earth. The carts reached it with great difficulty owing to the badness of the road. They had brought from Kabul to this place riwaj (rhubarb), which was mostly spoiled" (Tuzk-i-Jahangiri, translated by A. Rogers, vol. 1, p. 99).

89. Sarai Kharbuza is marked on Elphinston's map. Jahangir visited it in 1607 and described it in these words: "On Monday the 10th, the village of Kharbuza was our stage. The Ghakhars in earlier times had built a dome here and taken a toll from travellers. As the dome is shaped like a melon it became known by that name" (Tuzk-i- Jahangiri, translated by A. Rogers, vol. 1, p. 98).