Radcliffe Line

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 6/2/20

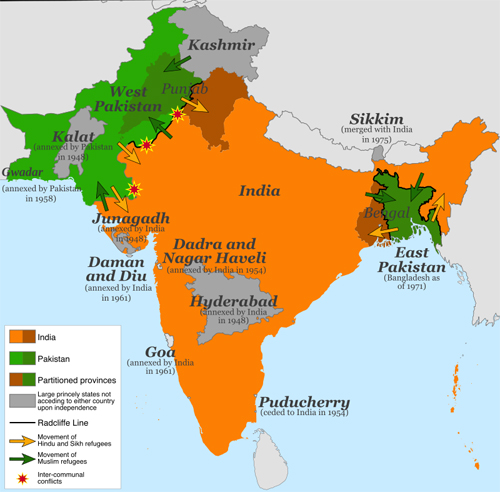

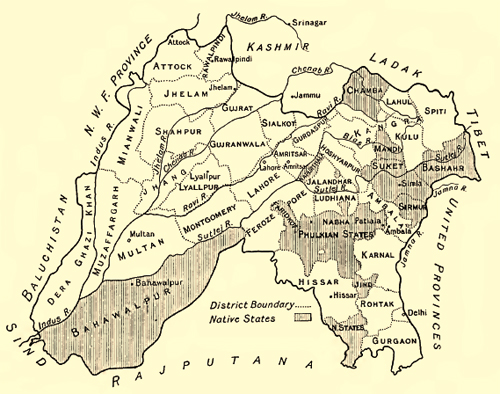

The regions affected by the extended Partition of India: green regions were all part of Pakistan by 1948, and orange part of India. The darker-shaded regions represent the Punjab and Bengal provinces partitioned by the Radcliffe Line. The grey areas represent some of the key princely states that were eventually integrated into India or Pakistan, but others which initially became independent are not shown.

The Radcliffe Line was the boundary demarcation line between the Indian and Pakistani portions of the Punjab and Bengal provinces of British India. It was named after its architect, Sir Cyril Radcliffe, who, as the joint chairman of the two boundary commissions for the two provinces, received the responsibility to equitably divide 175,000 square miles (450,000 km2) of territory with 88 million people.[1]

The demarcation line was published on 17 August 1947 upon the Partition of India. Today its western side still serves as the Indo-Pakistani border and the eastern side serves as the India-Bangladesh border.

Background

Events leading up to the Radcliffe Boundary Commissions

On 15 July 1947, the Indian Independence Act 1947 of the Parliament of the United Kingdom stipulated that British rule in India would come to an end just one month later, on 15 August 1947. The Act also stipulated the partition of the Presidencies and provinces of British India into two new sovereign dominions: India and Pakistan.

The Indian Independence Act, passed by the British parliament, abandoned the suzerainty of the British Crown over the princely states and dissolved the Indian Empire, and the rulers of the states were advised to accede to one of the new dominions.[2]

Pakistan was intended as a Muslim homeland, while India remained secular. Muslim-majority British provinces in the north were to become the foundation of Pakistan. The provinces of Baluchistan (91.8% Muslim before partition) and Sindh (72.7%) were granted entirely to Pakistan. However, two provinces did not have an overwhelming majority—Bengal in the north-east (54.4% Muslim) and the Punjab in the north-west (55.7% Muslim).[3] The western part of the Punjab became part of West Pakistan and the eastern part became the Indian state of East Punjab, which was later divided between a smaller Punjab State and two other states. Bengal was also partitioned, into East Bengal (in Pakistan) and West Bengal (in India). Before independence, the North-West Frontier Province (whose borders with Afghanistan had earlier been demarcated by the Durand Line) voted in a referendum to join Pakistan.[4] This controversial referendum was boycotted by Khudai Khidmatgars, the most popular Pashtun movement in the province at that time. The area is now a province in Pakistan called Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

The Punjab's population distribution was such that there was no line that could neatly divide Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs. Likewise, no line could appease the Muslim League, headed by Jinnah, and the Indian National Congress led by Jawaharlal Nehru and Vallabhbhai Patel, and by the British. Moreover, any division based on religious communities was sure to entail "cutting through road and rail communications, irrigation schemes, electric power systems and even individual landholdings."[5] However, a well-drawn line could minimize the separation of farmers from their fields, and also minimize the numbers of people who might feel forced to relocate.

As it turned out, on "the sub-continent as a whole, some 14 million people left their homes and set out by every means possible—by air, train, and road, in cars and lorries, in buses and bullock carts, but most of all on foot—to seek refuge with their own kind."[6] Many of them were slaughtered by an opposing side, some starved or died of exhaustion, while others were afflicted with "cholera, dysentery, and all those other diseases that afflict undernourished refugees everywhere".[7] Estimates of the number of people who died range between 200,000 (official British estimate at the time) and two million, with the consensus being around one million dead.[7]

Prior ideas of partition

The idea of partitioning the provinces of Bengal and Punjab had been present since the beginning of the 20th century. Bengal had in fact been partitioned by the then viceroy Lord Curzon in 1905, along with its adjoining regions. The resulting 'Eastern Bengal and Assam' province, with its capital at Dhaka, had a Muslim majority and the 'West Bengal' province, with its capital at Calcutta, had a Hindu majority. However, this partition of Bengal was reversed in 1911 in an effort to mollify Bengali nationalism.[8]

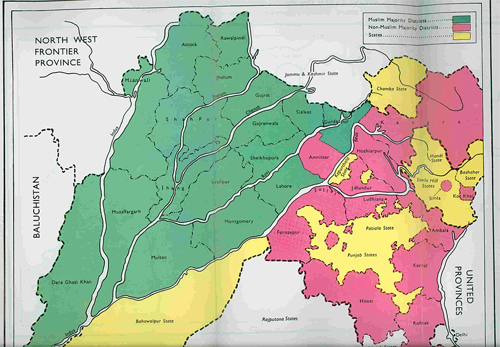

Proposals for partitioning Punjab had been made starting from 1908. Its proponents included the Hindu leader Bhai Parmanand, Congress leader Lala Lajpat Rai, industrialist G. D. Birla, and various Sikh leaders. After the Lahore resolution (1940) of the Muslim League demanding Pakistan, B. R. Ambedkar wrote a 400-page tract titled Thoughts on Pakistan,[9] wherein he discussed the boundaries of the Muslim and non-Muslim regions of Punjab and Bengal. His calculations showed a Muslim majority in 16 western districts of Punjab and non-Muslim majority in 13 eastern districts. In Bengal, he showed non-Muslim majority in 15 districts. He thought the Muslims could have no objection to redrawing provincial boundaries. If they did, "they [did] not understand the nature of their own demand".[10][11]

Districts of Punjab with Muslim (green) and non-Muslim (pink) majorities, as per 1941 census

After the breakdown of the 1945 Simla Conference of viceroy Lord Wavell, the idea of Pakistan began to be contemplated seriously. Sir Evan Jenkins, the private secretary of the viceroy (later the governor of Punjab), wrote a memorandum titled "Pakistan and the Punjab", where he discussed the issues surrounding the partition of Punjab. K. M. Panikkar, then prime minister of the Bikaner State, sent a memorandum to the viceroy titled "Next Step in India", wherein he recommended that the British government concede the principle of 'Muslim homeland' but carry out territorial adjustments to the Punjab and Bengal to meet the claims of the Hindus and Sikhs. Based on these discussions, the viceroy sent a note on "Pakistan theory" to the Secretary of State.[12] The viceroy informed the Secretary of State that Jinnah envisaged full provinces of Bengal and Punjab going to Pakistan with only minor adjustments, whereas Congress was expecting almost half of these provinces to remain in India. This essentially framed the problem of partition.[13]

The Secretary of State responded by directing Lord Wavell to send 'actual proposals for defining genuine Muslim areas'. The task fell on V. P. Menon, the Reforms Commissioner, and his colleague Sir B. N. Rau in the Reforms Office. They prepared a note called "Demarcation of Pakistan Areas", where they defined the western zone of Pakistan as consisting of Sindh, N.W.F.P., British Baluchistan and three western divisions of Punjab (Rawalpindi, Multan and Lahore). However, they noted that this allocation would leave 2.2 million Sikhs in the Pakistan area and about 1.5 million in India. Excluding the Amritsar and Gurdaspur districts of the Lahore Division from Pakistan would put a majority of Sikhs in India. (Amritsar had a non-Muslim majority and Gurdaspur a marginal Muslim majority.) To compensate for the exclusion of the Gurdaspur district, they included the entire Dinajpur district in the eastern zone of Pakistan, which similarly had a marginal Muslim majority. After receiving comments from John Thorne, member of the Executive Council in charge of Home affairs, Wavell forwarded the proposal to the Secretary of State. He justified the exclusion of the Amritsar district because of its sacredness to the Sikhs and that of Gurdaspur district because it had to go with Amritsar for 'geographical reasons'.[14][15][a] The Secretary of State commended the proposal and forwarded it to the India and Burma Committee, saying, "I do not think that any better division than the one the Viceroy proposes is likely to be found".[16]

Sikh concerns

While Master Tara Singh confused Rajagopalchari's offer with the Muslim League demand he could see that any division of Punjab would leave the Sikhs divided between Pakistan and Hindustan. He espoused the doctrine of self-reliance, opposed partition and called for independence on the grounds that no single religious community should control Punjab. Other Sikhs argued that just as Muslims feared Hindu domination the Sikhs also feared Muslim domination. Sikhs warned the British government that the morale of Sikh troops in the British Army would be affected if Pakistan was forced on them. Since Hindus seemed more concerned about the rest of India than Punjab, Master Tara Singh refused to ally with them and preferred to approach the British directly. Giani Kartar Singh drafted the scheme of a separate Sikh state if India was divided.[17]

During the Partition developments Jinnah offered Sikhs to live in Pakistan with safeguards for their rights. Sikhs refused because they opposed the concept of Pakistan and also because they were opposed to being a small minority within a Muslim majority. There are various reasons for the Sikh refusal to join Pakistan but one clear fact was that the Partition of Punjab left a deep impact on the Sikh psyche with many Sikh holy sites ending up in Pakistan.[18]

While the Congress had insisted for an India which was united and the Muslim League asked for a separate country, Dr. Vir Singh Bhatti distributed pamphlets for the creation of a separate Sikh state "Khalistan".[19] Sikh leaders who were unanimous in their opposition to Pakistan wanted a Sikh state to be created. Master Tara Singh wanted the right for an independent Khalistan to federate with either Hindustan or Pakistan. However, the Sikh state being proposed was for an area where no religion was in absolute majority.[20] Negotiations for the independent Sikh state had commenced at the end of World War II and the British initially agreed but the Sikhs withdrew this demand after pressure from Indian nationalists.[21] The proposals of the Cabinet Mission Plan had seriously jolted the Sikhs because while both the Congress and League could be satisfied the Sikhs saw nothing in it for themselves. as they would be subjected to a Muslim majority. Master Tara Singh protested this to Pethic-Lawrence on 5 May. By early September the Sikh leaders accepted both the long term and interim proposals despite their earlier rejection.[20] The Sikhs attached themselves to the Indian state with the promise of religious and cultural autonomy.[21]

Final negotiations

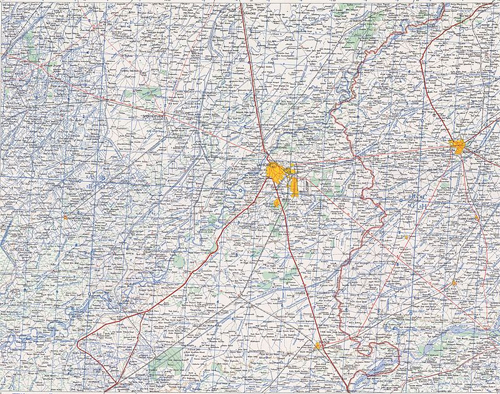

Pre-partition Punjab province

In March 1946, the British government sent a Cabinet Mission to India to find a solution to resolve the conflicting demands of Congress and the Muslim League. Congress agreed to allow Pakistan to be formed with 'genuine Muslim areas'. The Sikh leaders asked for a Sikh state with Ambala, Jalandher, Lahore Divisions with some districts from the Multan Division, which, however, did not meet the Cabinet delegates' agreement. In discussions with Jinnah, the Cabinet Mission offered either a 'smaller Pakistan' with all the Muslim-majority districts except Gurdaspur or a 'larger Pakistan' under the sovereignty of the Indian Union.[22] The Cabinet Mission came close to success with its proposal for an Indian Union under a federal scheme, but it fell apart in the end because of Nehru's opposition to a heavily decentralised India.[23][24]

Hindus and Sikhs in Punjab and Bengal clamoured for the division of these two provinces, arguing that if India could be divided along religious lines then so should these provinces because the Muslim majorities in both provinces were small.[25] The British agreed.[26][27] Scholar Akbar Ahmed says that the basic unit of administration in India was the province and not the district and that the district level division reduced the principle of partition to absurdity. According to Ahmed, such a division should have meant that Muslim estates in the United Provinces be separated and given to Pakistan.[28]

Sir Cripps remarked ″the Pakistan they are likely to get would be very different from what they wanted and it may not be worth their while.″[29] On 8 March the Congress passed a resolution to divide Punjab.[30]

In March 1947, Lord Mountbatten arrived in India as the next viceroy, with an explicit mandate to achieve transfer of power before June 1948. Within ten days, Mountbatten's staff had categorically stated that Congress had conceded the Pakistan demand except for the 13 eastern districts of Punjab (including Amritsar and Gurdaspur).[31]

However, Jinnah held out. Through a series of six meetings with Mountbatten, he continued to maintain that his demand was for six full provinces. He "bitterly complained" that the Viceroy was ruining his Pakistan by cutting Punjab and Bengal in half as this would mean a 'moth-eaten Pakistan'.[32][33][34]

The Gurdaspur district remained a key contentious issue for the non-Muslims. Their members of the Punjab legislature made representations to Mountbatten's chief of staff Lord Ismay as well as the Governor telling them that Gurdaspur was a "non-Muslim district". They contended that even if it had a marginal Muslim majority of 51%, which they believed to be erroneous, the Muslims paid only 35% of the land revenue in the district.[35]

In April, Governor Evan Jenkins wrote a note to Mountbatten proposing that Punjab be divided along Muslim and non-Muslim majority districts, but "adjustments could be made by agreement" regarding the tehsils (subdistricts) contiguous to these districts. He proposed that a Boundary Commission be set up consisting of two Muslim and two non-Muslim members recommended by the Punjab Legislative Assembly. He also proposed that a British judge of the High Court be appointed as the chairman of the Commission.[36] Jinnah and the Muslim League continued to oppose the idea of partitioning the provinces, and the Sikhs were disturbed about the possibility of getting only 12 districts (without Gurdaspur). In this context the Partition Plan of 3 June was announced with a notional partition showing 17 districts of Punjab in Pakistan and 12 districts in India, along with the establishment of a Boundary Commission to decide the final boundary. In Sialkoti's view, this was done mainly to placate the Sikhs.[37]

Mountbatten decided to threaten Jinnah by drawing a line less favourable to Muslims and more favourable to Sikhs if he did not agree to partitioning Punjab and Bengal.[38] However, Lord Ismay prevailed that he should use 'hurt feelings' rather than threats to persuade Jinnah for partition. They ultimately succeeded.[39] On 2 June Jinnah once again approached Mountbatten to plead for the unity of Punjab and Bengal but Mountbatten threatened that ' 'You will lose Pakistan probably for good.' '[28]

Process and key people

A crude border had already been drawn up by Lord Wavell, the Viceroy of India prior to his replacement as Viceroy, in February 1947, by Lord Louis Mountbatten. In order to determine exactly which territories to assign to each country, in June 1947, Britain appointed Sir Cyril Radcliffe to chair two Boundary Commissions—one for Bengal and one for Punjab.[40]

The Commission was instructed to "demarcate the boundaries of the two parts of the Punjab on the basis of ascertaining the contiguous majority areas of Muslims and non-Muslims. In doing so, it will also take into account other factors."[41] Other factors were undefined, giving Radcliffe leeway, but included decisions regarding "natural boundaries, communications, watercourses and irrigation systems", as well as socio-political consideration.[42] Each commission also had 4 representatives—2 from the Indian National Congress and 2 from the Muslim League. Given the deadlock between the interests of the two sides and their rancorous relationship, the final decision was essentially Radcliffe's.

After arriving in India on 8 July 1947, Radcliffe was given just five weeks to decide on a border.[40] He soon met with his fellow college alumnus Mountbatten and travelled to Lahore and Calcutta to meet with commission members, chiefly Nehru from the Congress and Jinnah, president of the Muslim League.[43] He objected to the short time frame, but all parties were insistent that the line be finished by 15 August British withdrawal from India. Mountbatten had accepted the post as Viceroy on the condition of an early deadline.[44] The decision was completed just a couple of days before the withdrawal, but due to political manoeuvring, not published until 17 August 1947, two days after the grant of independence to India and Pakistan.[40]

Members of the Commissions

Each boundary commission consisted of 5 people – a chairman (Radcliffe), 2 members nominated by the Indian National Congress and 2 members nominated by the Muslim League.[45]

The Bengal Boundary Commission consisted of Justices C. C. Biswas, B. K. Mukherji, Abu Saleh Mohamed Akram and S.A.Rahman.[46]

The members of the Punjab Commission were Justices Mehr Chand Mahajan, Teja Singh, Din Mohamed and Muhammad Munir.[46]

Problems in the process

Boundary-making procedures

The Punjabi section of the Radcliffe Line

All lawyers by profession, Radcliffe and the other commissioners had all of the polish and none of the specialized knowledge needed for the task. They had no advisers to inform them of the well-established procedures and information needed to draw a boundary. Nor was there time to gather the survey and regional information. The absence of some experts and advisers, such as the United Nations, was deliberate, to avoid delay.[47] Britain's new Labour government "deep in wartime debt, simply couldn’t afford to hold on to its increasingly unstable empire."[48] "The absence of outside participants—for example, from the United Nations—also satisfied the British Government's urgent desire to save face by avoiding the appearance that it required outside help to govern—or stop governing—its own empire."[49]

Political representation

The equal representation given to politicians from Indian National Congress and the Muslim League appeared to provide balance, but instead created deadlock. The relationships were so tendentious that the judges "could hardly bear to speak to each other", and the agendas so at odds that there seemed to be little point anyway. Even worse, "the wife and two children of the Sikh judge in Lahore had been murdered by Muslims in Rawalpindi a few weeks earlier."[50]

In fact, minimizing the numbers of Hindus and Muslims on the wrong side of the line was not the only concern to balance. The Punjab Border Commission was to draw a border through the middle of an area home to the Sikh community.[51] Lord Islay was rueful for the British not to give more consideration to the community who, in his words, had "provided many thousands of splendid recruits for the Indian Army" in its service for the crown in World War I.[52] However, the Sikhs were militant in their opposition to any solution which would put their community in a Muslim ruled state. Moreover, many insisted on their own sovereign state, something no one else would agree to.[53]

Last of all, were the communities without any representation. The Bengal Border Commission representatives were chiefly concerned with the question of who would get Calcutta. The Buddhist tribes in the Chittagong Hill Tracts in Bengal had no official representation and were left totally without information to prepare for their situation until two days after the partition.[54]

Perceiving the situation as intractable and urgent, Radcliffe went on to make all the difficult decisions himself. This was impossible from inception, but Radcliffe seems to have had no doubt in himself and raised no official complaint or proposal to change the circumstances.[1]

Local knowledge

Before his appointment, Radcliffe had never visited India and knew no one there. To the British and the feuding politicians alike, this neutrality was looked upon as an asset; he was considered to be unbiased toward any of the parties, except of course Britain.[1] Only his private secretary, Christopher Beaumont, was familiar with the administration and life in the Punjab. Wanting to preserve the appearance of impartiality, Radcliffe also kept his distance from Viceroy Mountbatten.[5]

No amount of knowledge could produce a line that would completely avoid conflict; already, "sectarian riots in Punjab and Bengal dimmed hopes for a quick and dignified British withdrawal".[55] "Many of the seeds of postcolonial disorder in South Asia were sown much earlier, in a century and half of direct and indirect British control of large part of the region, but, as book after book has demonstrated, nothing in the complex tragedy of partition was inevitable."[56]

Haste and indifference

Radcliffe justified the casual division with the truism that no matter what he did, people would suffer. The thinking behind this justification may never be known since Radcliffe "destroyed all his papers before he left India".[57] He departed on Independence Day itself, before even the boundary awards were distributed. By his own admission, Radcliffe was heavily influenced by his lack of fitness for the Indian climate and his eagerness to depart India.[58]

The implementation was no less hasty than the process of drawing the border. On 16 August 1947 at 5:00 pm, the Indian and Pakistani representatives were given two hours to study copies, before the Radcliffe award was published on 17 August.[59]

Secrecy

To avoid disputes and delays, the division was done in secret. The final Awards were ready on 9 and 12 August, but not published until two days after the partition.

According to Read and Fisher, there is some circumstantial evidence that Nehru and Patel were secretly informed of the Punjab Award's contents on 9 or 10 August, either through Mountbatten or Radcliffe's Indian assistant secretary.[60] Regardless of how it transpired, the award was changed to put a salient east of the Sutlej canal within India's domain instead of Pakistan's. This area consisted of two Muslim-majority tehsils with a combined population of over half a million. There were two apparent reasons for the switch: the area housed an army arms depot, and contained the headwaters of a canal which irrigated the princely state of Bikaner, which would accede to India.[citation needed]

Implementation

After the partition, the fledgling governments of India and Pakistan were left with all responsibility to implement the border. After visiting Lahore in August, Viceroy Mountbatten hastily arranged a Punjab Boundary Force to keep the peace around Lahore, but 50,000 men was not enough to prevent thousands of killings, 77% of which were in the rural areas. Given the size of the territory, the force amounted to less than one soldier per square mile. This was not enough to protect the cities much less the caravans of the hundreds of thousands of refugees who were fleeing their homes in what would become Pakistan.[61]

Both India and Pakistan were loath to violate the agreement by supporting the rebellions of villages drawn on the wrong side of the border, as this could prompt a loss of face on the international stage and require the British or the UN to intervene. Border conflicts led to three wars, in 1947, 1965, and 1971, and the Kargil conflict of 1999.

Disputes along the Radcliffe Line

There were disputes regarding the Radcliffe Line's award of the Chittagong Hill Tracts and the Gurdaspur district. Disputes also evolved around the districts of Malda, Khulna, and Murshidabad in Bengal and the sub-division of Karimganj of Assam.

In addition to Gurdaspur's Muslim majority tehsils, Radcliffe also gave the Muslim majority tehsils of Ajnala (Amritsar District), Zira, Ferozpur (in Ferozpur District), Nakodar and Jullander (in Jullander District) to India instead of Pakistan.[62]

Punjab

Lahore

Lahore having Muslims in majority with about 64.5% percent but Hindus and Sikhs controlled approximately 80% of city's assets,[63] Radcliffe had originally planned to give Lahore to India.[64][65][66] When speaking with journalist Kuldip Nayar, he stated "I nearly gave you Lahore. ... But then I realised that Pakistan would not have any large city. I had already earmarked Calcutta for India."[64][65] When Sir Cyril Radcliffe was told that “the Muslims in Pakistan have a grievance that [he] favoured India”, he replied, “they should be thankful to me because I went out of the way to give them Lahore which deserved to go to India.”[65] But in actually it's only an argument because according to Independence Act, partition was based on majority of population not on assets.[67][need quotation to verify]

Ferozpur District

Indian historians now accept that Mountbatten probably did influence the Ferozpur award in India's favour.[68]