Infrastructure projects

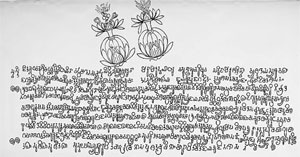

Silver punch mark coin of the Maurya empire, with symbols of wheel and elephant (3rd century BCE)

The empire built a strong economy from a solid infrastructure such as irrigation, temples, mines, and roads.[113][114] Ancient epigraphical evidence suggests Chandragupta, under counsel from Chanakya, started and completed many irrigation reservoirs and networks across the Indian subcontinent to ensure food supplies for the civilian population and the army, a practice continued by his dynastic successors.[102] Regional prosperity in agriculture was one of the required duties of his state officials.[115]

The strongest evidence of infrastructure development is found in the Junagadh rock inscription of Rudradaman in Gujarat, dated to about 150 CE. It states, among other things, that Rudradaman repaired and enlarged the reservoir and irrigation conduit infrastructure built by Chandragupta and enhanced by Asoka.[116] Chandragupta's empire also built mines, manufacturing centres, and networks for trading goods. His rule developed land routes to transport goods across the Indian subcontinent. Chandragupta expanded "roads suitable for carts" as he preferred those over narrow tracks suitable for only pack animals.[117]

According to Kaushik Roy, the Maurya dynasty rulers were "great road builders".[114] The Greek ambassador Megasthenes credited this tradition to Chandragupta [Sandrocottus !!!} after the completion of a thousand-mile-long highway connecting Chandragupta's [Sandrocottus !!!] capital Pataliputra [Palibothra !!!] in Bihar to Taxila in the north-west where he studied. The other major strategic road infrastructure credited to this tradition spread from Pataliputra in various directions, connecting it with Nepal, Kapilavastu, Dehradun, Mirzapur, Odisha, Andhra, and Karnataka.[114] Roy stated this network boosted trade and commerce, and helped move armies rapidly and efficiently.[114]

Megasthenes transformed India from a site of freakish difference and symmetrical opposition, to be wondered at or assimilated by imperial expansion, into a space of similarity and submerged cultural identity. India is now good to think with. The land has become an analogue of the Seleucid state and the Indica a text for working through issues of Seleucid state formation.

While Chandragupta Maurya's multiethnic, polyglot, expansionist kingdom certainly resembled the Seleucid state in outline and probably generated parallel mechanisms of territorial control, Megasthenes' ethnography went beyond this to emphasize consonance with the Seleucid world: certain of India's characteristics, appearing for the first time in ethnography, resemble Seleucid state structures too closely to be anything but observations or fabrications of similarity. The strongest case is the existence of autonomous, democratically governed cities within Megasthenes' Indian kingdom. The coexistence of independent and dependent cities within the same realm is one of the most striking characteristics of the Seleucid empire; it is unattested for the Mauryan kingdom. Megasthenes seems to have deliberately constructed a parallel system of irregular political sovereignty to better support the analogy between the two states. Other parallels include royal land ownership, the capital-on-the-river, the construction of roads and milestones, and various duties of the monarch.

-- Chapter 1: India – Diplomacy and Ethnography at the Mauryan Empire, Excerpt from "The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in the Seleucid Empire", by Paul J. Kosmin

Chandragupta and Chanakya seeded weapon manufacturing centres, and kept them as a state monopoly of the state. The state, however, encouraged competing private parties to operate mines and supply these centres.[118] [Roy, Kaushik (2012), Hinduism and the Ethics of Warfare in South Asia: From Antiquity to the Present]

The Economic, Political and Military Background, Excerpt from Hinduism and the Ethics of Warfare in South Asia: From Antiquity to the Present

Roy, Kaushik

2012

THE ECONOMIC, POLITICAL AND MILITARY BACKGROUND

After late in the sixth century BCE, Magadha emerged as the most powerful mahajanapada. Bimbisara, the ruler of Magadha (546-494 BCE), was known as seniya (one with sena). D. N. Jha asserts that Bimbisara was probably the first ruler in India with a regular standing army. Bimbisara annexed Anga. Bimbisara's son and successor, Ajatasatru, not only fortified Rajagriha (the capital of Magadha) with a forty-kilometer-long wall but also sent one of his ministers (a Brahmin named Vassakara) to sow dissension among the Lichchhavi tribes.20 [Jha, Early India, pp. 84- 6, 90.]Ajatasatru was able to overthrow the Vajjis through the policy of bheda followed by Vassakara.21 [KA, Part III, by Kangle, p. 11.] Kautilya's concept of kutayuddha was probably shaped by such historical events.

In 413 BCE, Shishunaga, the viceroy/governor of Benaras, became the ruler, and in 321 BCE the Shishunaga dynasty was overthrown by Mahapadma Nanda. Mahapadma, a Sudra, not only annexed Kalinga but also increased the strength of the army.22 [Jha, Early India, p. 87.] The Vishnu Purana and the Brahmanda Purana say that the Nandas ruled for 100 years.23 [Mital. Kautilaa Arthasastra Revisited. p. 60.] Alexander crossed the Hindu Kush mountain range in 327 BCE, but he then left after a brief sojourn in north-west India. Hence, no direct confrontation between the Greeks and the Nanda Empire occurred.

Chandragupta, like Mahapadma Nanda, was a Sudra. Chandragupta's mother, Mura, was probably the daughter of a Persian merchant. Reflecting the historical reality, the Arthasastra, unlike the vedas, never argue that the vijigishu should always come from the Kshatriya rank. Chandragupta seized Magadha around 32I BCE. By 312 BCE, he had completed the conquest of north and north-west India. If we believe the Mudraraksa (a fictional political drama in Sanskrit, by Vishakadatta, composed between the fourth and the seventh century CE), Chandragupta probably first acquired Punjab and then, with the help of Chanakya, moved towards the Nanda Empire. Paurava, who was ruling as a client ruler on behalf of Alexander, was killed before 318 BCE. The Mudraraksa tells us that Chandragupta, with the aid of some mercenaries from the north-west frontier tribes, laid siege to Kusumapura, the capital of Magadha. In the Questions of Milinda there is a reference to Bhaddasala. a general belonging to the Nandas, who fought against Chandragupta. Chandragupta defeated Seleucus in 305 BCE in a series of encounters along the river Indus. Megasthenes came to the Maurya court as an ambassador around 302 BCE and resided in India for four years. Around 297 BCE, Chandragupta passed away.24 [Kane, History of Dharmasastra, vol. I, Part I, pp. 173-4, 184, 186, 217-18.]

As regards the nature of the Maurya Empire, historians [???] are divided into two camps. While R. K. Mookerji25 [R. K. Mookerji, Chandragupta Maurya and His Times (n.d.; reprint, New Delhi: Motilal Banrasidas, 1960).] and D. N. Jha argue that it was a centralized empire, Gerard Fussman26 [Gerard Fussman, 'Central and Provincial Administration in Ancient India: The Problem of the Mauryan Empire', Indian Historical Review, vol. 14, nos. 1-2 (1988), pp. 43-72.] and Burton Stein27 [Burton Stein, A History of India (1998; reprint, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2004), pp. 78- 83.] claim that the Maurya Empire was a decentralized political entity. Some factual statements point to the fact that the Maurya Empire was a centralized bureaucratic polity. The Mauryas, like the Romans, were great road builders, and all the roads led to Pataliputra. Megasthenes noted that the thousand-mile- long royal highway connected Pataliputra to Taxila.28 [Mital, Kautilya Arthasastra Revisited, p. 29.] Pataliputra was connected to Nepal via Vaishali. From there a road passed through Champaran to Kapilavastu, Kalsi (DehraDun District), and Hazara up to Peshawar. Another network of roads connected Pataliputra to Sasaram, Mirzapur and central India. Yet, another road connected Pataliputra to Kalinga, Andhra and Karnataka, the southernmost limit of the empire.29 [Jha, Early India, p. 102.] These roads, besides facilitating trade and commerce, also functioned as military highways.

Jha claims that the Maurya economy was a sort of command economy. The Maurya polity exercised rigid control through a number of superintendents who presided over all trade and commercial activities. The metallurgy and mining industries were highly developed and were state monopolies. The monopoly rights of the state over mineral resources gave it exclusive control over the manufacture of metal weaponry.30 [Ibid., pp. 102.-5.] However, at times, mining was leased out to contractors. India produced high-quality steel, and the metal workers of Asia Minor adopted the techniques of Indian steel making.31 [Mital, Kautilya Arthasastra Revisited, p. 32.] Kautilya tells us about a die-striking (punch-marking) system but is unaware of casting coins in mould.32[Sil, Kautilya's Arthasastra, p. 25.]Cunningham held that the most ancient coins, those of Dhanadeva and Visikhadeva, are ‘certainly not older than the second century B.C.’, and this determination may be accepted, so far as the inscribed coins are concerned. Of course many of the punch-marked and cast coins without legends may be much older. The coins of both — Visikhadeva and Dhanadeva were simply cast in moulds, and evidently are of much the same date. Either prince may be regarded as the predecessor of the other. The coins, Nos. 8-11, doubtfully ascribed to Sivadatta, are also cast; as are the curious little pieces, Nos. 12 and 13 (PL XIX, 14), exhibiting the fish, svastika, ‘taurine, and an object which seems to me to be intended for a steelyard balance, but is described by Cunningham as an axe....

The simple process of making coins by casting in a mould seems to be little inferior in antiquity in India to that of stamping bars or ingots. Comparatively few of the numerous cast coins of ancient India are blank on the reverse. Most of them have a device or legend, or both, on each face, and were made by joining two moulds together. All the cast coins are of copper, including in that term various alloys. The most ancient examples probably are to be found among the rude pieces which are abundant in Oudh, Benares, and the neighbouring districts.

Cunningham considered the chaitya and tree coin of C.A.I., Pl. 1, 29, to be ‘rather rare’; but I should be disposed to call it ‘rather common’. Six examples of it have been catalogued, ranging in weight from 27-5 to 61 grains. No. 16 with the legend Kumhama is novel, and I cannot explain the meaning of the word. No. 19 is the largest rectangular cast coin that I have seen.

The circular cast coins, no doubt, were, to a large extent, contemporary with the rectangular ones. The types ‘chaitya and elephant’ and ‘chaitya and bull’ served as models for the much improved anonymous coins struck by some of the Western Satraps between 225 and 236 A.D. (C.M.I, p. 7, with correction of date of No. 10 from 129 to 158, Rapson); and this fact helps us to fix a posterior limit for the cast coinage in Ujjain and the neighbourhood. Of course, in different parts of India the practice varied greatly, and the old-fashioned methods of coining must have lingered in some places longer than in others; but in the Panjab and upper Gangetic provinces the cast coins are, I should think, probably all earlier than 100 A.D. They must have been driven out of circulation largely by the abundant copper issues of the Kushan kings. In Malwa (Avanti, Ujjain), as remarked above, the cast coinage may have lasted until 200 A.D., or even a little later.

-- Coins of Ancient India: Catalogue of the Coins in the Indian Museum, Calcutta, Volume 1, by Vincent A. Smith, M.A. F.R.N.S., M.R.A.S., I.C.S. Retd.

The Magadhan state functioned as a cash economy.33 [D. D. Kosambi, The Culture and Civilization of Ancient India in Historical Outline (n.d.; reprint, New Delhi: Vikas, 2001), p. 154.] Money was used for trade as well as for paying the state's civilian and military officials.34 [Jha, Early India, p. 102.]

Megasthenes tells us that soldiers were paid and equipped by the state. Hence, it seems that the Mauryas maintained a standing army and not merely a militia.35 [Biren Bonnerjea, 'Peace and War in Hindu Culture', Primitive Man: Quarterly Journal of the Catholic Anthropological Conference, vol. 7, no. 3 (1934), p. 36.] On the other hand, opines P.C. Chakravarti, the existence of armed trade and craft guilds with their private militias points to the fact that the Maurya Empire was a weak state. Not only did the private militias of these armed srenis provide protection to these organizations from brigands and highwayman, but during emergencies the ruler also hired them to fight internal as well as external enemies. These armed guilds occasionally engaged in private warfare and, in a way, constituted semi-autonomous states within a state.36 [P.C. Chakravarti, The Art of War in Ancient India (1941; reprint, New Delhi: Low Price Publications, 1989), pp. 6, 8.] It seems that the Mauryan Empire was not uniformly administered and was partially centralized and partially decentralized.

Romila Thapar takes a middle position and claims that the level of control exercised by the Maurya central government over different regions varied with distance. The inner core of the Maurya Empire was the metropolitan state of Magadha, which was ruled directly by the emperor from Pataliputra. Beyond the metropolitan state was the outer core of the empire, which comprised north and central India. The outer core region was divided into several provinces ruled by viceroys appointed by the emperor at Pataliputra. Most of the viceroys were princes of the royal family. The control of the central government at Pataliputra over the outer core region was substantial, but less than its control over the metropolitan state. Beyond the outer core was the periphery, which was comprised of north-west India and Deccan (the region south of the Narmada River). The periphery was ruled by several hereditary vassal chiefs and tribal leaders who accepted the political suzerainty of the Mauryan emperor at Pataliputra. It goes without saying that the control exercised by the central government at Pataliputra over the distant periphery was weakest. The central government did not interfere in the internal affairs of the vassal kingdoms, but it did control the foreign and military policies of the vassal chiefs.37 [Romila Thapar, The Mauryas Revisited (1987; reprint, Calcutta: K. P. Bagchi & Company, 1993).] This three-tier model of Thapar seems to be the most appropriate one for explaining the structure of the Maurya Empire. It is to be noted that the Arthasastra also speaks of regions ruled directly by the vijigishu; the janapadas (fertile agricultural land dotted with urban centres), which were ruled by chiefs and officials appointed by the vijigishu and hereditary vassal chiefs; and the forest regions under indirect control of the vijigishu. As a basis of comparison, the Shang Empire of China seems to have been more centralized than the Mauryan Empire because the former political entity had the capacity to conscript the common people for civil engineering projects and distributed grain through a system of centrally administered state granaries).38 [Thomas M. Kane, Ancient China on Postmodern War: Enduring Ideas from the Chinese Strategic Tradition (London/New York: Routledge, 2007), p. 29.]

Buddhism focused mainly on moksa. The arthasastra school, asserts Sil, emerged as a reaction to Buddhism. The arthasastra tradition emphasizes materialism rather than morality. The arthasastra writers divide the goals of human life into chatuvarga (four categories): dharma (morality), artha (wealth), kama (desires) and moksa. And of these four, artha occupies the most prominent place. Kautilya himself says that material well-being is supreme, because spiritual well-being and sensual pleasures depend on material well-being. The arthasastra means the sastra (theory) of artha. The meaning of artha changes with circumstances; broadly, it refers to wealth and territory with human population. Kautilya's Arthasastra does not really deal with the theory of the generation of wealth but is a treatise on statecraft. Kautilya says that the source of the livelihood of men is wealth and that the means for the attainment and protection of artha constitutes the theory of politics. Kautilya aims to educate the prince on the acquisition of material welfare (labha) and its maintenance through good governance.39 [Sil, Kautilya's Arthasastra, pp. 20-1.] The objective of Kautilya's theory is to lay bare the study of politics, wealth and practical expediency. The subjects covered are administration, law, order and justice, finance, foreign policy, internal security and defence against external powers.40 [Rashed Uz Zaman, 'Kautilya: The Indian Strategic Thinker and Indian Strategic Culture', Comparative Strategy, vol. 25, no. 3 (2006), p. 235.] The arthasastra tradition, claims Ashok S. Chousalkar, is based on the Lokayata philosophy, which emphasized analysis of concrete facts. [!!!] The Lokayatas deduced their conclusions from human behaviour and attempted an inductive investigation of the polity.41 [Ashok S. Chousalkar, A Comparative Study of Theory of Rebellion in Kautilya and Aristotle (New Delhi: Indological Book House, 1990), p. 65.] In the following sections, Kautilya's philosophical ideas are compared to and contrasted with both Western and Chinese philosophies.

They considered economic prosperity essential to the pursuit of dharma (virtuous life) and adopted a policy of avoiding war with diplomacy yet continuously preparing the army for war to defend its interests and other ideas in the Arthashastra.[119][120]

Arts and architecture

The evidence of arts and architecture during Chandragupta's [Sandrocottus !!!] time is mostly limited to texts such as those by Megasthenes and Kautilya.

The edict inscriptions and carvings on monumental pillars are attributed to his grandson Ashoka. The texts imply the existence of cities, public works, and prosperous architecture but the historicity of these is in question.[121]

Archeological discoveries in the modern age, such as those Didarganj Yakshi discovered in 1917 buried beneath the banks of the Ganges suggest exceptional artisanal accomplishment.[122][123] The site was dated to 3rd century BCE by many scholars[122][123] but later dates such as the Kushan era (1st-4th century CE) have also been proposed.

The Didarganj Yakshi [???] is one of the finest examples of very early Indian [???] stone statues. It used to be dated to the 3rd century BCE, as it has the fine Mauryan polish associated with Mauryan art. But this is also found on later sculptures and it is now usually dated to approximately the 2nd century CE, based on the analysis of shape and ornamentation, or the 1st century CE. The treatment of the forelock in particular is said to be characteristically Kushan....

The statue's nose was damaged during a travelling exhibition, The Festival of India, en route to Smithsonian Institution and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., leading to a decision not to send it abroad again.

-- Didarganj Yakshi, by Wikipedia

The competing theories state that the art linked to Chandragupta Maurya's dynasty was learnt from the Greeks and West Asia in the years Alexander the Great waged war; or that these artifacts belong to an older indigenous Indian tradition.[124] Frederick Asher of the University of Minnesota says "we cannot pretend to have definitive answers; and perhaps, as with most art, we must recognize that there is no single answer or explanation".[125]

Succession, renunciation, and death (Sallekhana)

1,300 years Old Shravanabelagola relief shows death of Chandragupta after taking the vow of Sallekhana. Some consider it about the legend of his [???] arrival with Bhadrabahu.[2][10][11]

A statue depicting Chandrgupta Maurya (right) with his spiritual mentor Acharya Bhadrabahu at Shravanabelagola.

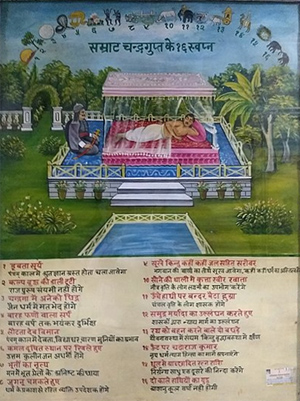

Chandragupta Maurya having 16 auspicious dreams in Jainism

The circumstances and year of Chandragupta's death are unclear and disputed.[2][10][11] According to Digambara Jain accounts that, Bhadrabahu forecasted a 12-year famine because of all the killing and violence during the conquests by Chandragupta Maurya. He led a group of Jain monks to south India, where Chandragupta Maurya joined him as a monk after abdicated his kingdom to his son Bindusara. Together, states a Digambara legend, Chandragupta and Bhadrabahu moved to Shravanabelagola, in present-day south Karnataka.[126] These Jain accounts appeared in texts such as Brihakathā kośa (931 CE) of Harishena, Bhadrabāhu charita (1450 CE) of Ratnanandi, Munivaṃsa bhyudaya (1680 CE) and Rajavali kathe.[127][128][129] Chandragupta lived as an ascetic at Shravanabelagola for several years before fasting to death as per the Jain practice of sallekhana, according to the Digambara legend.[130][26][131]

In accordance with the Digambara tradition, the hill on which Chandragupta is stated to have performed asceticism is now known as Chandragiri hill, and Digambaras believe that Chandragupta Maurya erected an ancient temple that now survives as the Chandragupta basadi.[1] According to Roy, Chandragupta's abdication of throne may be dated to c. 298 BCE, and his death to c. 297 BCE.[58] His grandson was emperor Ashoka who is famed for his historic pillars and his role in helping spread Buddhism outside of ancient India.[132][133]

Regarding the inscriptions describing the relation of Bhadrabahu and Chandragupta Maurya, Radha Kumud Mookerji writes,

The oldest inscription of about 600 AD associated "the pair (yugma), Bhadrabahu along with Chandragupta Muni." Two inscriptions of about 900 AD on the Kaveri near Seringapatam describe the summit of a hill called Chandragiri as marked by the footprints of Bhadrabahu and Chandragupta munipati. A Shravanabelagola inscription of 1129 mentions Bhadrabahu "Shrutakevali", and Chandragupta who acquired such merit that he was worshipped by the forest deities. Another inscription of 1163 similarly couples and describes them. A third inscription of the year 1432 speaks of Yatindra Bhadrabahu, and his disciple Chandragupta, the fame of whose penance spread into other words.[134]

A limited hangout is a form of deception, misdirection, or coverup often associated with intelligence agencies involving a release or "mea culpa" type of confession of only part of a set of previously hidden sensitive information, that establishes credibility for the one releasing the information who by the very act of confession appears to be "coming clean" and acting with integrity; but in actuality by withholding key facts is protecting a deeper crime and those who could be exposed if the whole truth came out. In effect, if an array of offenses or misdeeds is suspected, this confession admits to a lesser offense while covering up the greater ones.

A limited hangout typically is a response to lower the pressure felt from inquisitive investigators pursuing clues that threaten to expose everything, and the disclosure is often combined with red herrings or propaganda elements that lead to false trails, distractions, or ideological disinformation; thus allowing covert or criminal elements to continue in their improper activities.

Victor Marchetti wrote: "A 'limited hangout' is spy jargon for a favorite and frequently used gimmick of the clandestine professionals. When their veil of secrecy is shredded and they can no longer rely on a phony cover story to misinform the public, they resort to admitting - sometimes even volunteering - some of the truth while still managing to withhold the key and damaging facts in the case. The public, however, is usually so intrigued by the new information that it never thinks to pursue the matter further."

-- Limited Hangout, by Wikipedia

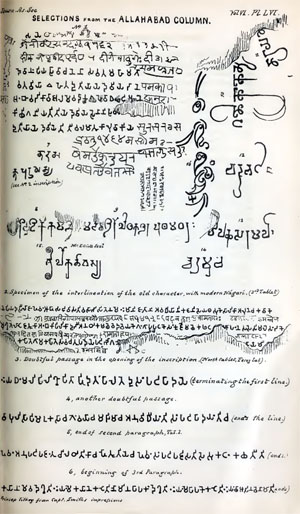

While recognising, approximately, the period to which the characters really belong, Mr. Rice (loc. cit. p. 15) arrived at the conclusion that, “if this interesting inscription did not precede the Christian era, it unquestionably belongs to the earliest part of that era and is certainly not later than about 100 A.D." But there are no substantial grounds for this view, which depends chiefly upon Mr. Rice’s acceptance as genuine, of the spurious Western Ganga grants...

We may now proceed to examine the real historical bearings of this inscription. It is not dated. But the lithographic Plate which is given by Mr. Rice, shews that the engraving of it is to be allotted to approximately the seventh century A.D.: it may possibly be a trifle earlier; and equally, it may possibly be somewhat later. And, interpreting the record in the customary manner, viz. as referring to an event almost exactly synchronous with the engraving of it, we can only take it as commemorating the death of a Jain teacher named Prabhachandra, in or very near to the period A.D. 600 to 700. Who this Prabhachandra was, I am not at present able to say. But he cannot be Prabhachandra I. of the pattavali of the Sarasvati-Gachchha (ante, Vol. XX. p. 351), unless the chronological details of that record, — according to which Prabhachandra I., became pontiff in A.D. 396, — are open to very considerable rectification.

-- Bhadrabahu, Chandragupta, and Sravana-Belgola, by J.F. Fleet, Bo.C.S., M.R.A.S., C.I.E.

Along with texts, several Digambara Jain inscriptions dating from the 7th–15th century refer to Bhadrabahu and a Prabhacandra. Later Digambara tradition identified the Prabhacandra as Chandragupta, and some modern era scholars have accepted this Digambara tradition while others have not, [2][10][11] Several of the late Digambara inscriptions and texts in Karnataka state the journey started from Ujjain and not Pataliputra (as stated in some Digambara texts).[10][11]

Jeffery D. Long – a scholar of Jain and Hindu studies – says in one Digambara version, it was Samprati Chandragupta who renounced, migrated and performed sallekhana in Shravanabelagola. Long states scholars attribute the disintegration of the Maurya empire to the times and actions of Samprati Chandragupta – the grandson of Ashoka and great-great-grandson of Chandragupta Maurya. The two Chandraguptas have been confused to be the same in some Digambara legends.[135]

Scholar of Jain studies and Sanskrit Paul Dundas says the Svetambara tradition of Jainism disputes the ancient Digambara legends. According to a 5th-century text of the Svetambara Jains, the Digambara sect of Jainism was founded 609 years after Mahavira's death, or in 1st-century CE.[136] Digambaras wrote their own versions and legends after the 5th-century, with their first expanded Digambara version of sectarian split within Jainism appearing in the 10th-century.[136] The Svetambaras texts describe Bhadrabahu was based near Nepalese foothills of the Himalayas in 3rd-century BCE, who neither moved nor travelled with Chandragupta Maurya to the south; rather, he died near Pataliputra, according to the Svetambara Jains.[10][137][138]

The 12th-century Svetambara Jain legend by Hemachandra presents a different picture. The Hemachandra version includes stories about Jain monks who could become invisible to steal food from royal storage and the Jain Brahmin Chanakya using violence and cunning tactics to expand Chandragupta's kingdom and increase royal revenues.[25] It states in verses 8.415 to 8.435, that for 15 years as king, Chandragupta was a follower of non-Jain "ascetics with the wrong view of religion" (non-Jain) and "lusted for women". Chanakya, who was a Jain follower, persuaded Chandragupta to convert to Jainism by showing that Jain ascetics avoided women and focused on their religion.[25] The legend mentions Chanakya aiding the premature birth of Bindusara,[25] It states in verse 8.444 that "Chandragupta died in meditation (can possibly be sallekhana.) and went to heaven".[139] According to Hemachandra's legend, Chanakya also performed sallekhana. [139]

The Footprints of Chandragupta Maurya on Chandragiri Hill, where Chandragupta (the unifier of India and founder of the Maurya Dynasty) performed Sallekhana.

According to V. R. Ramachandra Dikshitar – an Indologist and historian, several of the Digambara legends mention Prabhacandra, who had been misidentified as Chandragupta Maurya particularly after the original publication on Shravanabelagola epigraphy by B. Lewis Rice. The earliest and most important inscriptions mention Prabhacandra, which Rice presumed may have been the "clerical name assumed by Chadragupta Maurya" after he renounced and moved with Bhadrabahu from Pataliputra. Dikshitar stated there is no evidence to support this and Prabhacandra was an important Jain monk scholar who migrated centuries after Chandragupta Maurya's death.[2] Other scholars have taken Rice's deduction of Chandragupta Maurya retiring and dying in Shravanabelagola as the working hypothesis, since no alternate historical information or evidence is available about Chandragupta's final years and death.[2]

28. History. It has been said that the Hindus possess no national history. Max Muller accepts this proposition as a postulate, builds on it and explains the so-called absence of anything like historical literature among the Hindus to their being a nation of philosophers. "Greece and India are, indeed, the two opposite poles in the historical development of the Aryan man. To the Greek, existence is full of life and reality, to the Hindu, it is a dream, a delusion. The Greek is at home where he is born, all his energies belong to his country, he stands or falls with his party, and is ready to sacrifice even his life to the glory and independence of Hellas. The Hindu enters this world as a stranger, all his thoughts are directed to another world, he takes no part even where he is driven to act, and when he sacrifices his life, it is but to be delivered from it."1 [ASL, 9.]...

H. H. Wilson in his admirable Introduction to his translation of the Visnu Purana, while dealing with the contents of the Third Book observes that a very large portion of the contents of the Itihasas and and Puranas is genuine and writes: —

"The arrangement of the Vedas and other writings considered by the Hindus— being, in fact, the authorities of their religious rites and beliefs — which is described in the beginning of the Third book, is of much importance to the History of the Hindu Literature and of the Hindu religion. The sage Vyasa is here represented not as the author but the arranger or the compiler of the Vedas, the Itihasas and the Puranas. His name denotes his character meaning the 'arranger' or 'distributor', and the recurrence of many Vyasas, many individuals who remodelled the Hindu scriptures, has nothing in it, that is improbable, except the fabulous intervals by which their labours are separated. The re-arranging, the re-fashioning, of old materials is nothing more than the progress of time would be likely to render necessary. The last recognised compilation is that of Krishna Dvaipayana, assisted by Brahmans, who were already conversant with the subjects respectively assigned to them. They were the members of the college or school supposed by the Hindus to have flourished in a period more remote, no doubt, than the truth, but not at all unlikely to have been instituted at some time prior to the accounts of India which we owe to Greek writers and in which we see enough of the system to justify our inferring that it was then entire. That there have been other Vyasas and other schools since that date, that Brahmans unknown to fame have re-modelled some of the Hindu scriptures, and especially the Puranas, cannot reasonably be counted, after dispassionately weighing the strong internal evidence, which all of them afford, of their intermixture of unauthorized and comparatively modern ingredients. But the same internal testimony furnishes proof equally decisive, of the anterior existence of ancient materials, and it is, therefore, as idle as it is irrational, to dispute the antiquity or the authenticity of the contents of the Puranas, in the face of abundant positive and circumstantial evidence of the prevalence of the doctrines, which they teach, the currency of the legends which they narrate, and the integrity of the institutions which they describe at least three centuries before the Christian Era. But the origin and development of their doctrines, traditions and institutions were not the work of a day, and the testimony that establishes their existence three centuries before Christianity, carries it back to a much more remote antiquity, to an antiquity, that is, probably, not surpassed by any of the prevailing fictions, institutions or beliefs of the ancient world."

Again, in dealing with the contents of the Fourth Amsa of the Visnu Purana, the Professor remarks: —

"The Fourth Book contains all that the Hindus have of their Ancient History. It is a tolerably comprehensive list of dynasties and individuals, it is a barren record of events. It can scarcely be doubted, however, that much of it is a genuine chronicle of persons, if not of occurrences. That it is discredited by palpable absurdities in regard to the longevity of the princes of the earlier dynasties, must be granted, and the particulars preserved of some of them are trivial and fabulous. Still there is an artificial simplicity and consistency in the succession of persons, and a possibility and probability in some of the transactions, which give to these traditions the semblance of authenticity, and render it likely that these are not altogether without foundation. At any rate, in the absence of all other sources of information the record, such as it is, deserves not to be altogether set aside.

It is not essential to its celebrity or its usefulness, that any exact chronological adjustment of the different reigns should be attempted. Their distribution amongst the several Yugas, undertaken by Sir William Jones, or his Pandits, finds no countenance from the original texts, rather than an identical notice of the age in which a particular monarch ruled or the general fact that the dynasties prior to Krishna precede the time of the Great War and the beginning of the Kali Age, both which events are placed five thousand years ago. This, may, or may not, be too remote, but it is sufficient, in a subject where precision is impossible, to be satisfied with the general impression, that, in the dynasties of Kings detailed in Puranas, we have a record, which, although it cannot fail to have suffered detriment from age, and may have been injured by careless or injudicious compilation, preserves an account not wholly undeserving of confidence, of the establishment and succession of regular monarchies, amongst the Hindus, from as early an era, and for as continuous a duration, as any in the credible annals of mankind."

-- History of Classical Sanskrit Literature, by Kavyavinoda, Sahityaratnakara M. Krishnamachariar, M.A., M.I., Ph.D., Member of the Royal Asiatic Society of London (Of the Madras Judicial Service), Assisted by His Son M. Srinivasachariar, B.A., B.L., Advocate, Madras, 1937

Legacy

A memorial to Chandragupta Maurya exists on Chandragiri hill in Shravanabelagola, Karnataka.[140] The Indian Postal Service issued a commemorative postage stamp honouring Chandragupta Maurya in 2001.[141]

See also

• List of Indian monarchs

• List of Jain Empires and Dynasties

• Mauryan art

• Shashigupta

Notes

1. Some early printed editions of Justin's work wrongly mentioned "Alexandrum" instead of "Nandrum"; this error was corrected in philologist J. W. McCrindle's 1893 translation. In the 20th century, historians Hem Chandra Raychaudhuri and R. C. Majumdar believed "Alexandrum" to be correct reading, and theorized that Justin refers to a meeting between Chandragupta and Alexander the Great ("Alexandrum"). However, this is incorrect: research by historian Alfred von Gutschmid in the preceding century had clearly established that "Nandrum" is the correct reading supported by multiple manuscripts: only a single defective manuscript mentions "Alexandrum" in the margin.[44]

1. According to Grainger, Seleucus "must ... have held Aria" (Herat), and furthermore, his "son Antiochos was active there fifteen years later". (Grainger, John D. 1990, 2014. Seleukos Nikator: Constructing a Hellenistic Kingdom. Routledge. p. 109).

References

Citations

1. Mookerji 1988, p. 40.

2. Dikshitar 1993, pp. 264–266.

3. Chandragupta Maurya, Emperor of India Archived 10 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopædia Britannica

4. Upinder Singh 2016, p. 330.

5. Upinder Singh 2016, p. 331.

6. Majumdar, R. C.; Raychauduhuri, H. C.; Datta, Kalikinkar (1960), An Advanced History of India, London: Macmillan & Company Ltd; New York: St Martin's Press, If the Jaina tradition is to be believed, Chandragupta was converted to the religion of Mahavira. He is said to have abdicated his throne and passed his last days at Sravana Belgola in Mysore. Greek evidence, however, suggests that the first Maurya did not give up the performance of sacrificial rites and was far from following the Jaina creed of Ahimsa or non-injury to animals. He took delight in hunting, a practice that was continued by his son and alluded to by his grandson in his eighth Rock Edict. It is, however, possible that in his last days he showed some predilection for Jainism ...

7. The authors and their affiliations listed in the title page of the reference (which has the Wikipedia page An Advanced History of India) are: R. C. Majumdar, M.A., Ph.D. Vice-Chancellor, Dacca University; H. C. Raychaudhuri, M.A., Ph.D., Carmichael Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Calcutta University; and Kalikinkar Datta, M.A., Ph.D. Premchand Raychand Scholar, Mount Medallist, Griffith Prizeman, Professor and Head of the Department of History, Patna College, Patna

8. Mookerji 1988, pp. 2-14, 229-235.

9. Mookerji 1988, pp. 3-14.

10. Wiley 2009, pp. 50–52.

11. Fleet 1892, pp. 156–162.

12. Mookerji 1988, pp. 5-7.

13. Upinder Singh 2017, pp. 264–265.

14. Mookerji 1988, pp. 7–9.

15. Edward James Rapson; Wolseley Haig; Richard Burn; Henry Dodwell; Mortimer Wheeler, eds. (1968). The Cambridge History of India. 4. p. 470. "His surname Maurya is explained by Indian authorities as mean 'son of Mura,' who is described as a concubine of the king.

16. Mookerji 1988, pp. 9–11.

17. Mookerji 1988, p. 13.

18. Mookerji 1988, pp. 15-18.

19. note

20. Mookerji 1988, pp. 7–13.

21. Mookerji 1988, p. 14.

22. Mookerji 1988, pp. 13-15.

23. Thapar 1961, p. 12.

24. Mookerji 1988, pp. 13-14.

25. Hemacandra 1998, pp. 155–157, 168–188.

26. Jones & Ryan 2006, p. xxviii.

27. Kulke & Rothermund 2004, p. 59-65.

28. Jaini 1991, pp. 43–44.

29. Upādhye 1977, pp. 272–273.

30. Raychaudhuri 1923, p. 142.

31. Raychaudhuri 1923, p. 137.

32. Raychaudhuri 1923, p. 138.

33. Thapar 1961, p. 13.

34. Raychaudhuri 1967, pp. 134–142.

35. Habib & Jha 2004, p. 15.

36. Mookerji 1988, p. 16.

37. Raychaudhuri 1967, p. 143.

38. Mookerji 1988, p. 6.

39. Mookerji 1988, pp. 15–17.

40. Modelski, George (1964). "Kautilya: Foreign Policy and International System in the Ancient Hindu World". American Political Science Review. Cambridge University Press. 58 (3): 549–560. doi:10.2307/1953131. JSTOR 1953131.; Quote: "Kautilya is believed to have been Chanakya, a Brahmin who served as Chief Minister to Chandragupta (321–296 B.C.), the founder of the Mauryan Empire."

41. Mookerji 1988, pp. 19–20.

42. Mookerji 1988, p. 18.

43. Habib & Jha 2004, p. 14.

44. Trautmann 1970, pp. 240-241.

45. Mookerji 1988, p. 32.

46. Mookerji 1988, p. 22.

47. Hemacandra 1998, pp. 175–188.

48. Raychaudhuri 1967, pp. 144-145.

49. Raychaudhuri 1967, p. 144.

50. Mookerji 1988, p. 33.

51. Malalasekera 2002, p. 383.

52. Mookerji 1988, pp. 33-34.

53. Stoneman 2019, p. 155.

54. Thapar 2013, pp. 362–364.

55. Sen 1895, pp. 26–32.

56. Mookerji 1988, pp. 28–33.

57. Roy 2012, pp. 27, 61-62.

58. Roy 2012, pp. 61–62.

59. Grant 2010, p. 49.

60. Bhattacharyya 1977, p. 8.

61. Hemacandra 1998, pp. 176–177.

62. Mookerji 1988, p. 34.

63. Roy 2012, p. 62.

64. Mookerji 1988, pp. 2, 25-29.

65. Sastri 1988, p. 26.

66. Mookerji 1988, pp. 6-8, 31-33.

67. Boesche 2003, pp. 9–37.

68. Mookerji 1988, pp. 2-3, 35-38.

69. Appian, p. 55.

70. Mookerji 1988, pp. 36–37, 105.

71. Walter Eugene, Clark (1919). "The Importance of Hellenism from the Point of View of Indic-Philology". Classical Philology. 14 (4): 297–313. doi:10.1086/360246.

72. "Strabo 15.2.1(9)". Archived from the original on 3 February 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

73. Barua 2005, pp. 13-15.

74. Thomas McEvilley, "The Shape of Ancient Thought", Allworth Press, New York, 2002, ISBN 1581152035, p.367

75. India, the Ancient Past, Burjor Avari, p. 106-107

76. Majumdar 2003, p. 105.

77. Tarn, W. W. (1940). "Two Notes on Seleucid History: 1. Seleucus' 500 Elephants, 2. Tarmita". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 60: 84–94. doi:10.2307/626263. JSTOR 626263.

78. Mookerji 1988, p. 38.

79. Raychaudhuri 1967, p. 18.

80. Zvelebil 1973, pp. 53-54.

81. Mookerji 1988, pp. 41–42.

82. Upinder Singh 2016, pp. 330–331.

83. Raychaudhuri 1967, p. 139.

84. Thapar 2004, p. 177.

85. Arora, U. P. (1991). "The Indika of Megasthenes — an Appraisal". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 72/73 (1/4): 307–329. JSTOR 41694901.

86. Roy, Raja Ram Mohan (24 November 2015). India before Alexander: A New Chronology. Mount Meru publishing.

87. Arya, Vedveer (24 January 2020). The Chronology of India: From Mahabharata to Medieval Era - Vol I. Aryabhata Publications.

88. Raychaudhuri 1967, pp. 139-140.

89. Raychaudhuri 1967, p. 140.

90. Kulke & Rothermund 2004, p. 61.

91. Dupree 2014, pp. 285–289.

92. Dupont-Sommer, André (1970). "Une nouvelle inscription araméenne d'Asoka trouvée dans la vallée du Laghman (Afghanistan)". Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. 114 (1): 158–173. doi:10.3406/crai.1970.12491.

93. Salomon 1998, pp. 194, 199–200 with footnote 2.

94. Habib & Jha 2004, p. 19.

95. Kulke & Rothermund 2004, p. 64.

96. Boesche 2003, p. 7-18.

97. Mookerji 1988, pp. 1-4.

98. Mookerji 1988, pp. 13–18.

99. Boesche 2003, pp. 7–18.

100. MV Krishna Rao (1958, Reprinted 1979), Studies in Kautilya, 2nd Edition, OCLC 551238868, ISBN 978-8121502429, pages 13–14, 231–233

101. Olivelle 2013, pp. 31–38.

102. Allchin & Erdosy 1995, pp. 187–194.

103. Modelski, George (1964). "Kautilya: Foreign Policy and International System in the Ancient Hindu World". American Political Science Review. 58 (3): 549–560. doi:10.2307/1953131. JSTOR 1953131.; Quote: "Kautilya is believed to have been Chanakya, a Brahmin who served as Chief Minister to Chandragupta (321–296 B.C.), the founder of the Mauryan Empire."

104. Upinder Singh 2017, p. 220.

105. Allchin & Erdosy 1995, pp. 189–192.

106. Eraly 2002, pp. 414–415.

107. Sastri 1988, pp. 163–164.

108. Mookerji 1988, pp. 62–63, 79–80, 90, 159–160.

109. Sastri 1988, pp. 120–122.

110. Allan 1958, pp. 25–28.

111. Obeyesekere 1980, pp. 137–139 with footnote 3.

112. Albinski 1958, pp. 62–75.

113. Allchin & Erdosy 1995, pp. 187–195.

114. Roy 2012, pp. 62–63.

115. Allchin & Erdosy 1995, pp. 192–194.

116. Allchin & Erdosy 1995, p. 189.

117. Allchin & Erdosy 1995, pp. 194–195.

118. Roy 2012, pp. 63–64.

119. Roy 2012, pp. 64–68.

120. Olivelle 2013, pp. 49–51, 99–108, 277–294, 349–356, 373–382.

121. Harrison 2009, pp. 234–235.

122. Guha-Thakurta 2006, pp. 51–53, 58–59.

123. Varadpande 2006, pp. 32–34 with Figure 11.

124. Guha-Thakurta 2006, pp. 58–61.

125. Asher 2015, pp. 421–423.

126. Habib & Jha 2004, p. 20.

127. Mookerji 1988, pp. 39–40.

128. Samuel 2010, pp. 60.

129. Thapar 2004, p. 178.

130. Mookerji 1988, pp. 39–41, 60–64.

131. Bentley 1993, pp. 44–46.

132. Mookerji 1962, pp. 60–64.

133. Bentley 1993, pp. 44-46.

134. Mookerji, Radhakumud (1966). Chandragupta Maurya and His Times. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-0405-0.

135. Long 2013, pp. 60–61.

136. Dundas 2003, pp. 46–49.

137. Dundas 2003, pp. 46–49, 67–69.

138. Jyoti Prasad Jain 2005, pp. 65–67.

139. Hemacandra 1998, pp. 185–188.

140. Vallely 2018, pp. 182–183.

141. Commemorative postage stamp on Chandragupta Maurya Archived 27 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Press Information Bureau, Govt. of India

142. Ghosh 2001, pp. 44–46.

143. The Courtesan and the Sadhu, A Novel about Maya, Dharma, and God, October 2008, Dharma Vision LLC., ISBN 978-0-9818237-0-6, Library of Congress Control Number: 2008934274

144. Bhagwan Das Garga (1996). So Many Cinemas: The Motion Picture in India. Eminence Designs. p. 43. ISBN 978-81-900602-1-9.

145. Screen World Publication's 75 Glorious Years of Indian Cinema: Complete Filmography of All Films (silent & Hindi) Produced Between 1913-1988. Screen World Publication. 1988. p. 109.

146. Hervé Dumont (2009). L'Antiquité au cinéma: vérités, légendes et manipulations. Nouveau Monde. ISBN 978-2-84736-476-7.

147. "Chanakya Chandragupta (1977)". IMDb. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

148. "Television". The Indian Express. 8 September 1991. Archived from the original on 11 May 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

149. "Chandragupta Maurya comes to small screen". Zee News. 13 January 2011. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

150. "Chandragupta Maurya on Sony TV?". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 4 January 2016.

151. TV, Imagine. "Channel". TV Channel. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011.

152. "Real truth behind Chandragupta's birth, his first love Durdhara and journey to becoming the Mauryan King". 17 October 2016. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017.

153. "'Chandraguta Maurya' to launch in November on Sony TV". Archived from the original on 13 November 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

154. "Civilization VI – The Official Site | News | CIVILIZATION VI: RISE AND FALL - CHANDRAGUPTA LEADS INDIA". civilization.com. Archived from the original on 27 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July2018.

Sources

• Albinski, Henry S. (1958), "The Place of the Emperor Asoka in Ancient Indian Political Thought", Midwest Journal of Political Science, 2 (1): 62–75, doi:10.2307/2109166, JSTOR 2109166

• Allan, J (1958), The Cambridge Shorter History Of India, Cambridge University Press

• Allchin, F. R.; Erdosy, George (1995), The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-37695-2

• Appian, History of Rome, The Syrian Wars

• Asher, Frederick (2015), Brown, Rebecca M.; Hutton, Deborah S. (eds.), A Companion to Asian Art and Architecture, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-1-119-01953-4

• Barua, Pradeep (2005), The State at War in South Asia, 2, Nebraska Press, ISBN 9780803240612, via Project MUSE (subscription required)

• Bentley, Jerry (1993), Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times, Oxford University Press

• Bhattacharyya, P. K. (1977), Historical Geography of Madhyapradesh from Early Records, Motilal Banarsidass

• Boesche, Roger (2003), "Kautilya's Arthaśāstra on War and Diplomacy in Ancient India" (PDF), The Journal of Military History, 67 (1): 9, doi:10.1353/jmh.2003.0006, ISSN 0899-3718, S2CID 154243517

• Brown, Rebecca M.; Hutton, Deborah S. (22 June 2015), A Companion to Asian Art and Architecture, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 9781119019534

• Dikshitar, V. R. Ramachandra (1993), The Mauryan Polity, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., ISBN 978-81-208-1023-5

• Dundas, Paul (2003), The Jains, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-26605-5

• Dupree, Louis (2014), Afghanistan, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-1-4008-5891-0

• Eraly, Abraham (2002), Gem In The Lotus, Penguin, ISBN 978-93-5118-014-2

• Fleet, J.F. (1892), Bhadrabahu, Chandragupta and Shravanabelagola (Indian Antiquary), 21, Archaeological Society of India

• Ghosh, Ajit Kumar (2001), Dwijendralal Ray, Makers of Indian Literature (1st ed.), New Delhi: Sahitye Akademi, ISBN 978-81-260-1227-5

• Grant, R.G. (2010), Commanders, Penguin

• Guha-Thakurta, Tapati (2006), Chatterjee, Partha; Ghosh, Anjan (eds.), History and the Present, Anthem Press, ISBN 978-1-84331-224-6

• Habib, Irfan; Jha, Vivekanand (2004), Mauryan India, A People's History of India, Aligarh Historians Society / Tulika Books, ISBN 978-81-85229-92-8

• Harrison, Thomas (2009), The Great Empires of the Ancient World, Getty Publications, ISBN 978-0-89236-987-4

• Hemacandra (1998), The Lives of the Jain Elders, translated by R.C.C. Fynes, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-283227-6

• Jain, Jyoti Prasad (2005), Jaina Sources of the History of Ancient India: 100 BC - AD 900, Munshiram Manoharlal

• Jaini, Padmanabh S. (1991), Gender and Salvation, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-06820-9

• Jones, Constance; Ryan, James D. (2006), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5

• Long, Jeffery D (2013), Jainism: An Introduction, I.B.Tauris, ISBN 978-0-85771-392-6

• Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004), A History of India (4th ed.), London: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-15481-9

• Majumdar, R. C. (2003) [1952], Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0436-4

• Malalasekera, Gunapala Piyasena (2002), Encyclopaedia of Buddhism: Acala, Government of Ceylon

• Mandal, Dhaneshwar (2003), Ayodhya, Archaeology After Demolition: A Critique of the "new" and "fresh" Discoveries, Orient Blackswan, ISBN 9788125023449

• Mookerji, Radha Kumud (1962), Aśoka (3rd Revised., repr ed.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass (reprint 1995), ISBN 978-81208-058-28

• Mookerji, Radha Kumud (1988) [first published in 1966], Chandragupta Maurya and his times (4th ed.), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0433-3

• Obeyesekere, Gananath (1980), Doniger, Wendy (ed.), Karma and Rebirth in Classical Indian Traditions, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-03923-0

• Olivelle, Patrick (2013), King, Governance, and Law in Ancient India: Kauṭilya's Arthaśāstra, Oxford UK: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199891825

• Raychaudhuri, H. C. (1923), Political History of Ancient India: From the Accession of Parikshit to the Extinction of the Gupta Dynasty, Oxford University Press (1996 reprint, with B. N. Mukerjee Introduction)

• Raychaudhuri, H. C. (1967), "India in the Age of the Nandas / Chandragupta and Bindusara", in K. A. Nilakanta Sastri (ed.), Age of the Nandas and Mauryas (Second ed.), Motilal Banarsidass (1988 reprint), ISBN 978-81-208-0466-1

• Roy, Kaushik (2012), Hinduism and the Ethics of Warfare in South Asia: From Antiquity to the Present, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-01736-8

• Salomon, Richard (1998), Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-535666-3

• Samuel, Geoffrey (2010), The Origins of Yoga and Tantra. Indic Religions to the Thirteenth Century, Cambridge University Press

• Sastri, Kallidaikurichi Aiyah Nilakanta (1988), Age of the Nandas and Mauryas, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0466-1

• Sen, R.K. (1895), "Origin of the Maurya of Magadha and of Chanakya", Journal of the Buddhist Text Society of India, The Society

• Singh, Upinder (2016), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Pearson Education, ISBN 978-93-325-6996-6

• Singh, Upinder (2017), Political Violence in Ancient India, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-97527-9

• Stoneman, Richard (2019), The Greek Experience of India: From Alexander to the Indo-Greeks, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-18538-5

• Thapar, Romila (1961), Aśoka and the Decline of the Mauryas, Oxford University Press

• Thapar, Romila (2004) [first published by Penguin in 2002], Early India: From the Origins to A.D. 1300, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-24225-8

• Thapar, Romila (2013), The Past Before Us, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-72651-2

• Trautmann, Thomas R. (1970), "Alexander and Nandrus in Justin 15.4.16.", Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, 51 (1/4)

• Upādhye, Ādinātha Neminātha (1977), Mahāvīra and His Teachings, Bhagavān Mahāvīra 2500th Nirvāṇa Mahotsava Samiti

• Vallely, Anne (2018), Kitts, Margo (ed.), Martyrdom, Self-Sacrifice, and Self-Immolation: Religious Perspectives on Suicide, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-065648-5

• Varadpande, Manohar Laxman (2006), Woman in Indian Sculpture, Abhinav, ISBN 978-81-7017-474-5

• Wiley, Kristi L. (16 July 2009), The A to Z of Jainism, Scarecrow, ISBN 978-0-8108-6821-2

• Zvelebil, Kamil (1973), The Smile of Murugan: On Tamil Literature of South India, BRILL, ISBN 90-04-03591-5

Further reading

Library resources about

• Bongard-Levin, Grigory Maksimovich (1985). Mauryan India. New Delhi: Sterling Publishers. OCLC 14395730.

• Kosmin, Paul J. (2014), The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in Seleucid Empire, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-72882-0

• Mani, Braj Ranjan (2005), Debrahmanising history: dominance and resistance in Indian society, Manohar, ISBN 978-81-7304-640-7

• Roy, Kaushik (2015), Warfare in Pre-British India–1500BCE to 1740CE, Routledge

• Sagar, Krishna Chandra (1992), Foreign Influence on Ancient India, Northern Book Centre, ISBN 9788172110284

External links

• Maurya and Sunga Art, N R Ray