by Nick Redfern

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

It was the evening of September 12, 1952, when all hell broke loose in and around the small West Virginia town of Flatwoods. Something foul and malignant paid the townsfolk a visit of the truly terrible kind. As of this writing, more than 60 years after chaos and calamity briefly ruled, the memory of that long-gone eve still provokes massive amounts of gossip, debate, wonder, and even terror for the approximately 350 people that current call Flatwoods their home. That the controversial encounter occurred at the same time as a veritable armada of flying saucers was seen in the skies of the nation's capital only raised the controversy level even higher. Was some form of terrible, alien monster roaming around Flatwoods on that long-gone night? Or, incredibly, do we need to look to none other than the U.S. government for the answers? We're on a hunt for what the townsfolk officially refer to today as -- no surprises here -- the Flatwoods Monster.

While the U.S. Air Force was busying itself with numerous UFO sightings on the night in question, startled Flatwoods townsfolk were dealing with something very different, indeed: the apparent crash-landing of, well, something atop a hill on land that belonged to a local farmer named G. Bailey Fisher. Chief among the witnesses were a Mrs. Kathleen May, a National Guardsman named Eugene Lemon, and a group of nearly hyperventilating teenagers. The group tentatively headed out together to the darkness-cloaked scene of the action, where they suddenly encountered a fiery ball of light that loomed ominously on the hill and emitted an unknown noxious substance that severely irritated the eyes and noses of all those present.

But all of that was suddenly forgotten when something terrifying loomed into view from the shadows of the surrounding trees. It was not one of those archetypal small, skinny, black-eyed, large-headed aliens, called "Greys," that have become so deeply ingrained in the fervid collective imagination of popular culture. No, this creature was 12ft (3.7m) tall, seemingly brightly illuminated from within, and had a head that appeared to be shrouded in some kind of cowl. One of the terrified witnesses said it resembled the spade symbol in a deck of playing cards.

As a showering array of flashing, arcing lights surrounded the beast, its glowing, penetrating, fiery eyes seemed to be fixed in the direction of the group. Not surprisingly, as the monstrosity began to glide above the ground toward them, they fled for their lives down the hill.

Returning tentatively to the scene a few hours later, the group were mightily relieved to find the monster now gone, but to where, exactly, no one ever knew. As a result, an enduring legend was born: More than six decades ago, a behemoth from another world paid the small, otherwise sleepy and innocuous town of Flatwoods a bone-chilling visit. Or did it? From within the once-secret files of the U.S. government we find a fantastically controversial story that suggests that the monster of Flatwoods may have been nothing less than a strange, perhaps even robotic creation of the American military. Sound bizarre? Well, that's exactly what it was.

THE U.S. MILITARY SECRETLY INVENTS A MONSTER

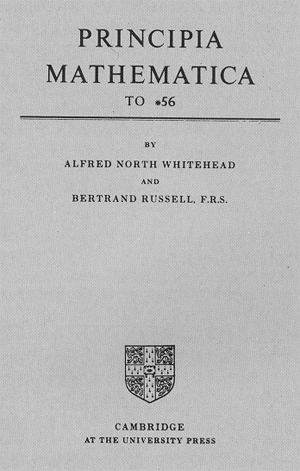

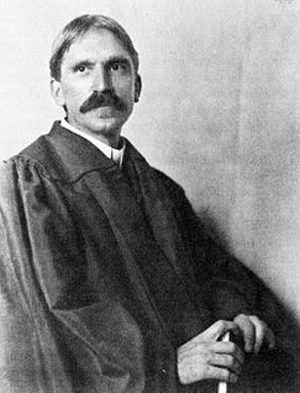

In 2010, the U.S. Air Force quietly declassified (via the terms of the Freedom of Information Act) an April 14, 1950, publication of the RAND Corporation bearing the title The Exploitation of Superstitions for Purposes of Psychological Warfare. Researched and prepared by a RAND employee named Jean M. Hungerford, who was under secret contract to the Air Force at the time, the document detailed the many and varied ways and means -- some truly ingenious -- that beliefs and superstitions relative to supernatural phenomena could be leveraged on the battlefield to frighten and, hence, weaken the enemy. One such curious caper of that era, carefully cited within the pages of the RAND report, involved the U.S. military spreading utterly false stories throughout the former Soviet Union that American troops regularly saw the Virgin Mary at the height of warfare, thus promulgating the idea that God was on the side of the land of the free.

With the Kennedy brothers, it was no longer purely a matter of national security. It was personal. Castro had not only survived the Bay of Pigs but been emboldened by it, openly mocking the United States' effete and quixotic attempts to bring him down. A smoldering President Kennedy demanded action. Sam Halpern, a veteran Agency officer, recalls Richard Bissell summoning him into his office. "He told us he had been chewed out in the cabinet room of the White House by the president and attorney general for sitting on his ass and not doing anything about Castro and the Castro regime." Bissell related the president's order: "Get rid of Castro."

Halpern wanted clarification. "What do the words 'get rid of' mean?" he asked Bissell.

"Use your imagination," Bissell responded. "No holds barred."

In the year ahead the Agency did indeed use its imagination. There was even a short-lived plan to convince the Cuban people of Christ's Second Coming, complete with aerial starbursts. "Elimination by illumination," the scheme was dubbed by one senior officer. But such silliness gave way to more deadly plans, including a contract on Castro's life offered to the Mafia. The Agency was determined to create chaos in Cuba, with a mix of sabotage, propaganda, and, if need be, outright assassination. The project was part of a broad-based action against Castro code-named Operation Mongoose.

-- The Book of Honor: The Secret Lives and Deaths of CIA Operatives, by Ted Gup

But what, you may well ask, does any of this have to do with the glowing-eyed beast that briefly haunted Flatwoods in September 1952? It is here that we finally get to the crux of that particularly fraught matter.

One particular item that Hungerford focused a great deal of her attention on was a book titled Magic: Top Secret. It was penned back in 1949 by a mysterious and controversial character named Jasper Maskelyne. Maskelyne was both a highly skilled magician and an employee of the British Army. His job during WWII was to come up with alternative ways and weapons with which to deceive and defeat the Nazis. That Maskelyne -- who came across in the pages of his book very much like the character "Q" from the James Bond novels and movies -- may have significantly exaggerated his wartime role for the readers of Magic: Top Secret suggests that his operations were not quite as exciting, or even as real, as he claimed them to be. But not for RAND, and certainly not for the U.S. Air Force, which practically hung upon Maskelyne's every word, particularly as it pertained to one very weird cloak-and-dagger operation.

According to Maskelyne, while fighting the Nazis in the mountains of Italy at the height of the War, the British Army came up with a brilliant but undeniably strange idea. They built what was essentially, in Maskelyne's very own words, "a gigantic scarecrow, about 12 feet [3.6m] high" that would "stagger forward under its own power and emit frightful flashes and bangs." The idea was to have those Italians who were not sympathetic to the Allies believe the strange contraption -- complete with "great electric blue sparks jumping from it" -- was none other than the devil himself, working hand in glove with the Brits in some terrible, Faustian pact to defeat the Axis powers (Maskelyne, 1949). The result: terror, chaos, and calamity broke out wherever and whenever the flashing creature made its unearthly appearance. Villagers that were hostile to the British locked themselves in their homes, thus giving Maskelyne and his colleagues a very good idea about how monstrous superstitions and devilish beliefs could significantly influence the tide of war. Fearful of going to hell for aiding Hitler's minions, those very same hostile Italian villagers closed ranks and thought twice about ever rendering aid to the Nazis again. The British government gained an advantage, the Nazis had suffered significant blows, and not a single shot from a rifle had to be fired -- all thanks to a fabricated, mechanized Satan.

The Pentagon creates a monster, © U.S. Air Force, 1950. Source: U.S. Air Force, under the terms of the Freedom of Information Act

U.S. Air Force

PROJECT RAND

RESEARCH MEMORANDUM

THE EXPLOITATION OF SUPERSTITIONS FOR PURPOSES OF PSYCHOLOGICAL WARFARE

Jean M. Hungerford

14 April 1950

The RAND Corporation

IT'S ALIVE!

Believe it or not, there are deep and undeniable parallels between the British Army's demonic caper and the events at Flatwoods that occurred less than a decade later. Both the UK military's scarecrow and the monster of the little West Virginia town were around 12 feet (3.6m) tall, both emitted bright, flashing lights and strange sparks that arced wildly into the air; and, perhaps most important of all, both were classic examples of how psychological warfare can help defeat an enemy. On this latter point, let's not forget that Jean M. Hungerford's RAND report was specifically prepared for psychological warfare planners in the U.S. Air Force, who took a great deal of interest in what the witnesses and the media were saying about the Flatwoods Monster and what they thought the creature was. Perhaps not surprisingly, the Air Force took a great deal of secret interest in the words of Jasper Maskelyne, too.

You'll recall that Maskelyne's escapades occurred in small, isolated areas that could have been easily and secretly monitored to see how effectively the ruses were working. Flatwoods, a town of fewer than 400 people even today, would have made just such an ideal location for the U.S. Air Force to test a similar device to Maskelyne's devil, and see how a monster could be "animated" and used to deceive and terrify. Doing this in a safe and secure environment such as Flatwoods would have provided the U.S. Air Force with plenty of food for thought about how such a weird weapon could be used against a superstitious or credulous enemy at the height of the Cold War -- if such a monstrosity were ever needed, of course.

THE ISSUE OF THE ACE OF SPADES

Interestingly, the primary witnesses to the Flatwoods Monster described the creature as having a head that resembled the spade design on a playing card. It so happens that this particular motif has played a leading role in more than a few psychological warfare operations orchestrated by the American military. By way of an example, a May 10, 1967, document titled Vietnam: PSYOP Directive: The Use of Superstitions in Psychological Operations in Vietnam describes how U.S. military forces learned that certain factions of North Vietnamese military personnel were "deathly afraid" of the ace of spades card and perceived it as an "omen of death." The author of the document (whose name is excised from the declassified papers) continues that, with this information in hand, American soldiers became "psy-warriors" and, "with the assistance of playing card manufacturers, began leaving the ominous card in battle areas and on patrols into enemy-held territory." Interestingly, files also show that the US. military had clearly done its homework on this matter, and came to realize that the dread of the ace of spades on the part of certain factions of the Vietnamese military dated back to the 19th century, when French Catholic missionaries to Vietnam encountered the Montagnard people of Vietnam's Central Highlands and learned how the imagery provoked terror in the region (Vietnam: PSYOP Directive: The Use of Superstitions in Psychological Operations in Vietnam, 1967).

In his autobiography, In the Midst of Wars, Lansdale gives an example of the counterterror tactics he employed in the Philippines. He tells how one psychological warfare operation "played upon the popular dread of an asuang, or vampire, to solve a difficult problem." The problem was that Lansdale wanted government troops to move out of a village and hunt Communist guerrillas in the hills, but the local politicians were afraid that if they did, the guerrillas would "swoop down on the village and the bigwigs would be victims." So, writes Lansdale:A combat psywar [psychological warfare] team was brought in. It planted stories among town residents of a vampire living on the hill where the Huks were based. Two nights later, after giving the stories time to circulate among Huk sympathizers in the town and make their way up to the hill camp, the psywar squad set up an ambush along a trail used by the Huks. When a Huk patrol came along the trail, the ambushers silently snatched the last man of the patrol, their move unseen in the dark night. They punctured his neck with two holes, vampire fashion, held the body up by the heels, drained it of blood, and put the corpse back on the trail. When the Huks returned to look for the missing man and found their bloodless comrade, every member of the patrol believed that the vampire had got him and that one of them would be next if they remained on the hill. When daylight came, the whole Huk squadron moved out of the vicinity.

Lansdale defines the incident as "low humor" and "an appropriate response ... to the glum and deadly practices of communists and other authoritarians."

-- The Phoenix Program, by Douglas Valentine

Two operations -- one at Flatwoods, West Virginia, and the other in Vietnam -- that involved psychological warfare strategists in the U.S. military, two operations that involved the deployment of playing card motifs, and two operations that were designed to provoke fear in the individuals targeted. Do we really need further evidence that the Flatwoods monster was the creation of officialdom? Finally, how truly ironic it would be if the U.S. Air Force had taken its inspiration and ideas from Jasper Maskelyne, a man whose claims and assertions are viewed by many today through deeply suspicious eyes. Deceit, duplicity, and deception, it seems, are the common threads that run through virtually the entire tapestry of this particular saga of monstrous secrets.

*************************

Chapter 7: Welcome to the Jungle, from "True Stories of Real-Life Monsters" [Excerpt]

by Nick Redfern

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

The very real possibility that the diabolical "creature" of Flatwoods, West Virginia, was an ingenious, robotic creation of the U.S. military is further bolstered by the revelation that the Department of Defense (DOD) was engaged in yet further bizarre monster-making and myth-spreading during this exact same time frame. Indeed, while a glowing-eyed beast of the night was terrifying the good folk of Flatwoods, West Virginia, Pentagon scientists and psychological warfare planners within the American military were spreading dark tales of blood-sucking, monstrous vampires roaming the wild depths of the Philippines.

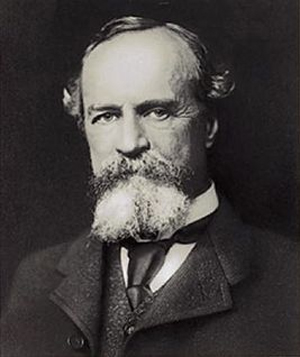

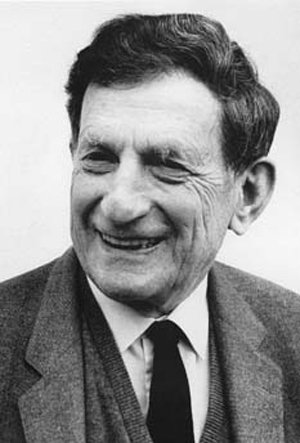

Major Edward Lansdale, the brains behind a monstrous vampire, © U.S. Air Force, 1963. Source: Wikipedia

The truly fascinating saga was one born out of the fertile and fantastical mind of Major General Edward G. Lansdale. During the hostilities of WWII, Lansdale spent a great deal of time working with personnel attached to the U.S. Office of Strategic Services, with whom he carefully developed and nurtured his very own weird ways of defeating the enemy -- in fact, just about any enemy. But it was when Lansdale was given a post-war assignment at HQ Air Forces Western Pacific in the Philippines that things really began to heat up and the strangeness rose to stratospheric levels.

At the specific insistence of the sixth president of the Philippines, Elpidio Rivera Quirino, Lansdale was brought in to work on a project of fantastic proportions with the Joint United States Military Assistance Group. The year, rather notably, was exactly the same as Flatwoods: 1952. As for the reason, it was to offer secret American military aid -- by virtually any means necessary -- and intelligence support in stamping out a growing uprising on the part of what were known as the Hukbalahap. During the Second World War, the Huks, as they came to be known, operated as guerrilla units in the Philippines with just one goal in mind: to wipe out the invading forces of the empire of Japan. And they didn't do a bad job of it, either. But when the war finally came to an end in 1945, the Huks quickly turned their attentions toward ousting the government of the Philippines. From 1946 onward, face-to-face confrontation between the Huks and the forces of the government and the military was commonplace. The time came, however, when enough was seen as being just about enough. Cue the stealthy entrance, stage left, of Major General Lansdale and his mysterious box of terrible tricks.

A BLOODSUCKER OF THE NIGHT

While deep in discussion with President Quirino and his staff about the varied ways and means available to defeat the Huks, Lansdale came to learn just how deeply influenced the latter were by certain local myths and legends. Lansdale had a sudden flash of brilliance: He decided to bring one of those same superstitions -- the shape-shifting Aswang vampire -- to life. The Aswangs were fearsome, bloodsucking monsters of gigantic proportions that were said to lurk deep within the jungles of the Philippines. As Lansdale learned to his profound interest, the Huks carefully and cautiously avoided any location where the predatory Aswangs were said to dwell and feast. Thus, an amazingly off-the-wall plan soon came to fruition. Decades after this previously classified operation was over, when he finally felt comfortable speaking out publicly, Lansdale himself had this to say on the controversial matter:

To the superstitious, the Huk battleground was a haunted place filled with ghosts and eerie creatures. A combat psy-war squad was brought in. It planted stories among town residents of an Aswang living on the hill where the Huks were based. Two nights later. after giving the stories time to make their way up to the hill camp, the psy-war squad set up an ambush along the trail used by the Huks (Lansdale, 1991).

It was then that things were taken to a whole new, and almost unbelievable, level. Lansdale's men were suddenly transformed from elite soldiers of the U.S. military into predatory beasts of the dark forest, simply by means of the power of suggestion and a much-feared myth seemingly brought to life. On the first night of the operation, the elite team carefully and stealthily followed a Huk patrol on its regular evening check of the area. It was then, when the skies and woods were at their absolute darkest, that they were suddenly and silently attacked from behind. The last man on the patrol was quickly plucked from the group and his neck was punctured with a specially crafted lethal weapon that had been designed to mimic the classic calling card of the legendary bloodsuckers: two deep and savage wounds to the neck. But that was only the beginning. The team then tied a rope around the ankles of the victim, threw the other end of the rope over the thick branch of a nearby tree, and hauled the man's body into the air to let it hang there -- upside down -- for hours, as the blood slowly drained out of the vicious, gaping neck wounds. Then, with the dastardly deed finally complete, the body of the Huk was carefully taken down and quietly dumped near the camp of his rebel comrades. The result, as Edward Lansdale noted, was as amazing as it was swift:

When the Huks returned to look for the missing man and found their bloodless comrade, every member of the patrol believed that the Aswang had got him and that one of them would be next if they remained on that hill. When daylight came, the whole Huk squadron moved out of the vicinity (Ibid.).

As a direct result of these actions, vitally important strategic ground was taken out of the hands of the Huk rebels. That a bloodsucking monster was brought to life, and quickly and deeply influenced the outcome of a military engagement, despite the fact that the same monster never really existed in the first place, is without doubt extraordinary. And, in light of the data contained in this chapter, those who dearly wish, or fully believe, the monster of Flatwoods to have been an entity of unknown origins, and that bloodthirsty Aswangs really are among us, might do well to reconsider those particular views. While it may be said that both monsters "lived" in some strange way, the nature of their odd, brief lives was even stranger than it would have been had they actually been fantastic beasts of flesh and blood.

In his autobiography, In the Midst of Wars, Lansdale gives an example of the counterterror tactics he employed in the Philippines. He tells how one psychological warfare operation "played upon the popular dread of an asuang, or vampire, to solve a difficult problem." The problem was that Lansdale wanted government troops to move out of a village and hunt Communist guerrillas in the hills, but the local politicians were afraid that if they did, the guerrillas would "swoop down on the village and the bigwigs would be victims." So, writes Lansdale:A combat psywar [psychological warfare] team was brought in. It planted stories among town residents of a vampire living on the hill where the Huks were based. Two nights later, after giving the stories time to circulate among Huk sympathizers in the town and make their way up to the hill camp, the psywar squad set up an ambush along a trail used by the Huks. When a Huk patrol came along the trail, the ambushers silently snatched the last man of the patrol, their move unseen in the dark night. They punctured his neck with two holes, vampire fashion, held the body up by the heels, drained it of blood, and put the corpse back on the trail. When the Huks returned to look for the missing man and found their bloodless comrade, every member of the patrol believed that the vampire had got him and that one of them would be next if they remained on the hill. When daylight came, the whole Huk squadron moved out of the vicinity.

Lansdale defines the incident as "low humor" and "an appropriate response ... to the glum and deadly practices of communists and other authoritarians."

-- The Phoenix Program, by Douglas Valentine

*************************

Chapter 8: Animal ESP and the U.S. Army, from "True Stories of Real-Life Monsters" [Excerpt]

by Nick Redfern

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

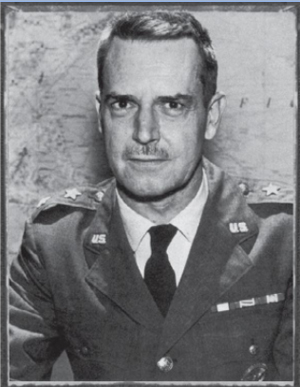

According to formerly classified U.S. Army documents, in the early 1950s, a Dr. Joseph Banks Rhine, Ph.D. of Duke University, was quietly approached by senior personnel in the American military to participate in a program of truly extraordinary and mind-boggling proportions. The clandestine operation was designed to determine if dogs, cats, and pigeons possessed any significant degree of extrasensory perception (ESP). The reason was as bizarre as it was controversial: to train those very same animals to use their near-magical powers of the mind to locate enemy land mines buried beneath war-torn battlefields. As for why Rhine was chosen for this weird, Lassie-meets-The X-Files project, the answer is very simple: Prior to his secret work with the Army, Rhine was a noted, albeit controversial figure within the field of paranormal research. (Indeed, he later became known as the father of modern parapsychology. A prestigious title, certainly. Not only that; it was Rhine who coined the term extrasensory perception, thus forever establishing for himself legendary status as a leading player within the realm of psychic phenomena.)

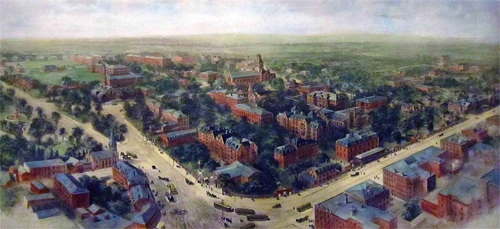

To understand what it was that prompted the United States Army to embark upon its grand, strange scheme, we have to go all the way back to the 1920s, when Rhine secured a master's degree and a doctorate in botany at the University of Chicago and began digging into matters relative to alternative science. From there, it was all very much uphill: Soon thereafter Rhine accepted a position at Duke University and began pursuing in earnest his burgeoning passion for ESP and the mysterious powers of the mind -- and not just human minds, but those of animals, too.

Rhine routinely used a pack of 25 Zener cards in his research. Named after their creator, Karl Zener, a psychologist who graduated from Harvard, taught at Princeton, and worked with the U.S. National Research Council, the cards display a variety of designs -- lines, crosses, squares, and circles. In a typical experiment the goal was to sit two people opposite one another, and have one act as the sender and the other as the receiver. The "sender" would focus intently on the image displayed on the card in front of him, while the "receiver" would try to divine that same image via psychic means. Sometimes it worked and sometimes it didn't, but for Rhine, even if it yielded a low success rate, well, it was still a success. So, he pressed on with his work with even greater intensity and focus. As a testament to this, by the early 1940s, the number of trials that he and his staff embarked on had reached almost one million.

[Paranormal Studies Laboratory]

[Someone has written on door: "Venkman Burn in Hell"]

[Dr. Peter Venkman] All right, I'm gonna turn over the next card.

I want you to concentrate.

I want you to tell me what you think it is.

[Male Student] Square.

[Dr. Peter Venkman] Good guess, but wrong.

[Administers Electric Shock]

[Dr. Peter Venkman] Clear your head.

All right. Tell me what you think it is.

[Female Student] Is it a star?

[Dr. Peter Venkman] It is a star. Very good. That's great.

All right. Think hard.

What is it?

[Male Student] Circle.

[Dr. Peter Venkman] Close.

But definitely wrong.

[Administers electric shock]

[Male Student] [Candy pops out of his mouth]

-- Ghostbusters, directed by Ivan Reitman

As a new decade progressed, and as Rhine's status, reputation, and (eventually) legend as a guru in psychic circles grew ever larger, it was not just his fellow parapsychologists, the general public, and the mainstream media that were looking at Rhine through interested and intrigued eyes. Little did Rhine suspect at the time that senior personnel behind the closed, cloaked doors of the Pentagon were doing exactly that, as well. They were hardly broadcasting that interest, however. Indeed, steps were taken to keep official interest in Rhine's work under secure wraps at all times, even when the man himself was carefully approached by government sources with the hopes of getting him onboard as a Cold War-era warrior of sorts.

DOGGEDLY LOOKING FOR MINES

It was a normal day in January 1952 -- or as normal as any day can ever be for someone whose routine involved the study of psychic phenomena -- when Rhine received in his office a telephone call of a kind that many might expect to see only in a Hollywood movie. A life-changing question was put to Rhine by the "Man in Black" at the other end of the line: Would he be interested in serving his country by heading up a classified project that could help save American lives and significantly strengthen U.S. national security, and all via psychic means, no less? Of course Rhine was interested! Thus began a most odd relationship between the psychic scientist and the top brass of the American military.

Having signed a lengthy and complex nondisclosure contract with the Army, Rhine was invited in February 1952 out to the Engineering Research and Development Laboratories of the Army's Virginia-based Fort Belvoir facility, where he was briefed on the ambitious scheme to turn animals into psychic spies and mine-detectors. Rhine was immediately hooked on the new and novel idea, and work began in earnest. Within days, the Army provided Rhine with half a dozen young German shepherds that were to function as his test subjects for about three months.

Psychic dogs of the military © U.S. Army, circa 1960s/1970s. Source: Wikipedia

Although the admittedly limited number of publicly available U.S. Army files on this matter do not fully describe how, exactly, Rhine and his cohorts tested the dogs' psychic powers, they do demonstrate that two dogs in particular scored high. Their names were Tessie and Binnie, and apparently they worked wonders locating dummy mines buried on remote stretches of California's sandy coastline in June of 1952. Rhine's own words, which were recorded on the same day of the initial experiment, are notable: "The success was high enough that it was soon evident that the dogs were alerting the mines before they set foot on the surface above them." And the Army's response was positively glowing, too: The result of the first day's total of 14 trials was 86 percent successful (Rhine, Final Report for Contract, 1953).

Tessie and Binnie continued to yield very impressive results, so much so that the military quickly took things to another, far more ambitious level. They moved away from the beach and buried a number of deactivated mines under the water at distances of anywhere from 40 to 60ft (12-18m) from the shore. When the paranormal pooches were brought to the beach shortly thereafter, they barked loudly, leaped out of the back of the vehicle, raced for the sea, and excitedly swam right to where the devices lay concealed below the churning waves. Rhine reported back to the Pentagon and got straight to the point: "There is at least no known way in which the dogs could have located the underwater mines except by extrasensory perception." The excited top brass didn't disagree. With Tessie and Binnie having quickly met with the Pentagon's approval, the military expanded its attention to include not just man's best friend, but also the arch enemy of that same best friend, the cat (Ibid.).

CURIOUS CATS AND PARANORMAL PIGEONS

Interestingly, much of the relevant data concerning how the several cats used in the program were taught to locate the mines remain classified under U.S. national security regulations. Nevertheless, we do have the following brief words from Rhine contained in the files, which make it clear that they predicted a successful outcome in this venture, as well: "Most of the things reported about dogs that suggested the possibility of ESP as a factor were also claimed for cats. Psychologically, the animals are close enough together to make a transfer of findings from one species to the other fairly likely." It's most regretful that the bulk of the cat-related files remain unreleased, since Rhine's statement that "a transfer of findings from one species to the other [was] fairly likely" appears to imply that plans were initiated to have the cats and dogs work together and actually combine their psychic skills to locate the mines -- an undeniably extraordinary idea (Ibid.).

Raising the seriously weird stakes even higher, the Army also wanted to see what Rhine thought about getting a small army of psychically gifted pigeons along for the ride, too. Evidently, this proved to be overly ambitious and not at all successful, as Rhine himself admitted to the Army: "The mystery of pigeon-homing and the possibility that extrasensory perception enters into that performance led us to undertake the solution of the problem of how these pigeons find their way home. At the termination of the contract the problem had not been solved" (Ibid.). As Rhine was careful to stress with respect to the pigeon-based studies, however,

researchers have ruled out all existing sensory hypotheses, thereby making extrasensory perception a more plausible interpretation than it has been hitherto. This research has opened up possibilities of importance not only within but far beyond the scope of the projects specifically dealt with. The problems raised on this project involve basic research that may remain in the category of the inapplicable for many years. Measured against this is the enormous value, not only to intelligence but to application in a wide range of military uses of extrasensory perception (Ibid.).

THE RESEARCH CONTINUES

If the enigmas of the animal brain could be used to locate land mines, then what else might they be capable of? The military clearly recognized the logic and full import of this question. But Pentagon staff had something else on their minds, too: Precisely how reliable were Rhine's tests? Could it not have just been the case, some sources within the Army began to speculate, that Tessie and Binnie were merely using their powerful sense of smell, rather than engaging any sort of paranormal talent, to find the mines? To his credit, Rhine did consider just such a possibility, and, as a direct result, both the tests and the attendant conditions were modified to make sure that Tessie and Binnie were not exposed to strong cross-winds that might have allowed the pair to uncover "chemical stimuli" from the mines. Again, this seemed not to affect their successes -- not for some time, anyway (Ibid.).

Rather oddly, the positive results started to drop off dramatically in 1953, which led Rhine to advise his Army contacts that "the thing that stands out is that the ability that is being measured is a very elusive and delicate one" (Ibid.). Indeed, it was this statement that ultimately led the Army to make the decision to close down the program. Again, not because of the lack of any success: The Tessie and Binnie saga strongly suggested that they had achieved something new and notable here. The problem for the Pentagon was that this success was fleeting and uncontrollable; it could not be predicted, let alone guaranteed. And it was this somewhat-haphazard success rate -- coupled with the fact that the military was still struggling to comprehend the realm of ESP -- that led to the termination of the operation (Ibid.).

Rhine was far from being deterred, however. He continued with his research for decades afterward, and penned a number of books on the subject, including New World of the Mind and Parapsychology Today. Although he died in 1980, his legacy as a prime mover in the arena of ESP lives on. As for Tessie and Binnie, one has to wonder if their presumed, advanced mind-powers led them to realize, in some curiously canine fashion, that they were helping Uncle Sam's efforts to keep the United States safe from overseas enemies. Or perhaps the prospect of racing around Californian beaches under the hot, West Coast sun in the summer of 1952 was just a big lark for them, and they ultimately went to their graves sadly unaware of their brief, yet without a doubt significant role in one of the U.S. government's strangest secret projects of all time.