Part 4 of 4

However, Whitehead did not agree with those who hold that the ideal solution of the science-religion conflict is the complete annihilation of religion. Whitehead, on the contrary, held that

we should aim at the integration of science and religion, and turn the impoverishing opposition between the two into an enriching contrast. According to Whitehead, both religion and science are important, and he wrote:

When we consider what religion is for mankind, and what science is, it is no exaggeration to say that the future course of history depends upon the decision of this generation as to the relation between them. (1926a [1967: 181])

Whitehead never sided with those who, in the name of science, oppose religion with a misplaced and dehumanizing rhetoric of disenchantment, nor with those who, in the name of religion, oppose science with a misplaced and dehumanizing exaltation of existent religious dogmas, codes of behavior, institutions, rituals, etc. As Whitehead wrote: “There is the hysteria of depreciation, and there is the opposite hysteria which dehumanizes in order to exalt” (1927 [1985: 91]). Whitehead, on the contrary, urged both scientific and religious leaders to observe “the utmost toleration of variety of opinion” (1926a [1967: 187]) as well as the following advice:

Every age produces people with clear logical intellects, and with the most praiseworthy grip of the importance of some sphere of human experience, who have elaborated, or inherited, a scheme of thought which exactly fits those experiences which claim their interest. Such people are apt resolutely to ignore, or to explain away, all evidence which confuses their scheme with contradictory instances. What they cannot fit in is for them nonsense. An unflinching determination to take the whole evidence into account is the only method of preservation against the fluctuating extremes of fashionable opinion. This advice seems so easy, and is in fact so difficult to follow (1926a [1967: 187]).

Whitehead’s advice of taking the whole evidence into account implies taking the inner life of religion into account and not only its external life:

Life is an internal fact for its own sake, before it is an external fact relating itself to others. The conduct of external life is conditioned by environment, but it receives its final quality, on which its worth depends, from the internal life which is the self-realization of existence. Religion is the art and the theory of the internal life of man, so far as it depends on the man himself and on what is permanent in the nature of things.

This doctrine is the direct negation of the theory that religion is primarily a social fact. Social facts are of great importance to religion, because there is no such thing as absolutely independent existence. You cannot abstract society from man; most psychology is herd-psychology. But all collective emotions leave untouched the awful ultimate fact, which is the human being, consciously alone with itself, for its own sake.

Religion is what the individual does with his own solitariness. (1926b [1996: 15–16])

Whitehead’s advice also implies the challenge to continually reshape the outer life of religion in accord with the scientific developments, while remaining faithful to its inner life. When taking into account science, religion runs the risk of collapsing. Indeed, while reshaping its outer life, religion can only avoid implosion by remaining faithful to its inner life. “Religions commit suicide”, according to Whitehead, when do they not find “their inspirations … in the primary expressions of the intuitions of the finest types of religious lives” (1926b [1996: 144]). And he writes:

Religion, therefore, while in the framing of dogmas it must admit modifications from the complete circle of our knowledge, still brings its own contribution of immediate experience. (1926b [1996: 79–80])

On the other hand, when religion shelters itself from the complete circle of knowledge, it also faces “decay” and, Whitehead adds, “the Church will perish unless it opens its window” (1926b [1996: 146]). So there really is no alternative. But that does not render the task at hand any easier.

Whitehead lists two necessary, but not sufficient, requirements for religious leaders to reshape, again and again, the outer expressions of their inner experiences: First, they should stop exaggerating the importance of the outer life of religion. Whitehead writes:

Collective enthusiasms, revivals, institutions, churches, rituals, bibles, codes of behavior, are the trappings of religion, its passing forms. They may be useful, or harmful; they may be authoritatively ordained, or merely temporary expedients. But the end of religion is beyond all this. (1926b [1996: 17])

Secondly, they should learn from scientists how to deal with continual revision. Whitehead writes:

When Darwin or Einstein proclaim theories which modify our ideas, it is a triumph for science. We do not go about saying that there is another defeat for science, because its old ideas have been abandoned. We know that another step of scientific insight has been gained.

Religion will not regain its old power until it can face change in the same spirit as does science. Its principles may be eternal, but the expression of those principles requires continual development. This evolution of religion is in the main a disengagement of its own proper ideas in terms of the imaginative picture of the world entertained in previous ages. Such a release from the bonds of imperfect science is all to the good. (1926a [1967: 188–189])

In this respect, Whitehead offers the following example:

The clash between religion and science, which has relegated the earth to the position of a second-rate planet attached to a second-rate sun, has been greatly to the benefit of the spirituality of religion by dispersing [a number of] medieval fancies. (1926a [1967: 190])

On the other hand, Whitehead is well aware that religion more often fails than succeeds in this respect, and he writes, for example, that both

Christianity and Buddhism … have suffered from the rise of … science, because neither of them had … the requisite flexibility of adaptation. (1926b [1996: 146])

If the condition of mutual tolerance is satisfied, then, according to Whitehead: “A clash of doctrines is not a disaster—it is an opportunity” (1926a [1967: 186]). In other words, if this condition is satisfied, then the clash between religion and science is an opportunity on the path toward their integration or, as Whitehead puts it:

The clash is a sign that there are wider truths and finer perspectives within which a reconciliation of a deeper religion and a more subtle science will be found. (1926a [1967: 185])

According to Whitehead, the task of philosophy is “to absorb into one system all sources of experience” (1926b [1996: 149]), including the intuitions at the basis of both science and religion, and in Religion in the Making, he expresses the basic religious intuition as follows:

There is a quality of life which lies always beyond the mere fact of life; and when we include the quality in the fact, there is still omitted the quality of the quality. It is not true that the finer quality is the direct associate of obvious happiness or obvious pleasure. Religion is the direct apprehension that, beyond such happiness and such pleasure remains the function of what is actual and passing, that it contributes its quality as an immortal fact to the order which informs the world. (1926b [1996: 80])

The first aspect of this dual intuition that

“our existence is more than a succession of bare facts”

GEORGES I. GURDJIEFF,

A WESTERNER WHO WENT ON THIS HIGHER TRIP

OR AT LEAST ON A LARGE PART OF THE TRIP, SAID:

YOU DON'T SEEM TO UNDERSTAND

YOU ARE IN PRISONIF YOU ARE TO GET OUT OF PRISON

THE FIRST THING YOU MUST REALIZE IS:

YOU ARE IN PRISON

IF YOU THINK

YOU'RE FREE YOU CAN'T ESCAPE.

-- Be Here Now, by "Ram Dass," aka The Lama Foundation

(idem) is that the quality or value of each of the successive occasions of life derives from a finer quality or value, which lies beyond the mere facts of life, and even beyond obvious happiness and pleasure, namely,

the finer quality or value of which life is informed by God. The second aspect is that each of the successive occasions of life contributes its quality or value as an immortal fact to God.

In Process and Reality, Whitehead absorbed this dual religious intuition in terms of the bipolar—primordial and consequent—nature of God.

God viewed as primordial does not determine the becoming of each actual occasion, but conditions it (cf. supra—the initial subjective aim). He does not force, but tenderly persuades each actual occasion to actualize—from “the absolute wealth of potentiality” (1929: 343)—value-potentials relevant for that particular becoming. “God”, according to Whitehead, “is the poet of the world, with tender patience leading it by his vision of truth, beauty, and goodness” (1929c [1985: 346]).

“The ultimate evil in the temporal world”, Whitehead writes,lies in the fact that the past fades, that time is a “perpetual perishing.” … In the temporal world, it is the empirical fact that process entails loss. (1929c [1985: 340])

In other words, from a merely factual point of view, “human life is a flash of occasional enjoyments lighting up a mass of pain and misery, a bagatelle of transient experience” (1926a [1967: 192]). According to Whitehead, however, this is not the whole story. On 8 April 1928, while preparing the Gifford Lectures that became Process and Reality, Whitehead wrote to Rosalind Greene:

I am working at my Giffords. The problem of problems which bothers me, is the real transitoriness of things—and yet!!—I am equally convinced that the great side of things is weaving something ageless and immortal: something in which personalities retain the wonder of their radiance—and the fluff sinks into utter triviality. But I cannot express it at all—no system of words seems up to the job. (Unpublished letter archived by the Whitehead Research Project)

Whitehead’s attempt to express it in Process and Reality reads:

There is another side to the nature of God which cannot be omitted. … God, as well as being primordial, is also consequent … God is dipolar. (1929c [1985: 345])

The consequent nature of God is his judgment on the world. He saves the world as it passes into the immediacy of his own life. It is the judgment of a tenderness which loses nothing that can be saved. (1929c [1985: 346])

The consequent nature of God is the fluent world become ‘everlasting’ … in God. (1929c [1985: 347])

Whitehead’s dual description of God as tender persuader and tender savior reveals his affinity with “the Galilean origin of Christianity” (1929c [1985: 343]). Indeed, his

theistic philosophy … does not emphasize the ruling Caesar, or the ruthless moralist, or the unmoved mover. It dwells upon the tender elements in the world, which slowly and in quietness operate by love. (idem)

One of the major reasons why Whitehead’s process philosophy is popular among theologians, and gave rise to process theology, is the fact that it helps to overcome the doctrine of an omnipotent God creating everything out of nothing. This creatio ex nihilo doctrine implies God’s responsibility for everything that is evil, and also that God is the only ultimate reality. In other words, it prevents the reconciliation of divine love and human suffering as well as the reconciliation of the various religious traditions, for example, theistic Christianity and nontheistic Buddhism. In yet other words, the creatio ex nihilo doctrine is a stumbling block for theologians involved in theodicy or interreligious dialogue. Contrary to it,

Whitehead’s process philosophy holds that there are three ultimate (but inseparable) aspects of total reality: God (the divine actual entity), the world (the universe of all finite actual occasions), and the creativity (the twofold power to exert efficient and final causation) that God and all finite actual occasions embody. The distinction between God and creativity (that God is not the only instance of creativity) implies that there is no God with the power completely to determine the becoming of all actual occasions in the world—they are instances of creativity too. In this sense,

God is not omnipotent, but can be conceived as “the fellow-sufferer who understands” (1929c [1985: 351]).

CHAPTER X. MAN AND GOD.§ 1. The subject of this chapter is that of the relation of man to his cause, or his past, and if we denominate the supposed First Cause of the world God, it will possess two main connections with the preceding inquiries. In the first place, the conception of a first cause of the world requires to be vindicated against the criticism stated in chapter ii. (§ 10). In the second place, we were led in the last chapter to explain the material cosmos as an interaction between God and the Ego, and to suggest positions which require further elucidation.

It was shown by an examination of the contradiction of causation in chapter ii. that a first cause of existence in general is an irrational conception, in chapter iii. (§ 11) that causation is a thoroughly anthropomorphic conception, derived from, and applicable to, the phenomenal world. On both these grounds, therefore, to say that God is the First Cause of the world is to say that God is the First Cause of the phenomenal world, i.e., the cause of the world-process. For the category of causation does not carry beyond the process of Evolution or the phenomenal world (cp. ch. ii. § 9). But if so interpreted, there is no absurdity in the conception of a First Cause. Our reason impels us to ask for a cause of the changes we see, and at the same time forbids us to say that they arise out of nothing, i.e. causelessly. But if we applied these postulates of our reason to all things, to existence as such, they would lead us into the absurdity that all things having been caused, they must ultimately have been caused by nothing. But if this is impossible, if we cannot derive existence out of nothing, then there must be at least one existence which has never come into existence. Such an existence would be an ultimate fact, and the question as to its cause would be unmeaning. For being non-phenomenal, the idea of coming into existence, or Becoming, which is a conception applying only to the facts of the phenomenal world, would not here be applicable. If, then, God is such an existence, such a conception of God satisfies both the requirements of our demand for causation and solves the difficulty which the conception of a First Cause presents, if taken in an absolute sense.

Thus God is, (1) the unbecome and non-phenomenal Cause of the world-process — the Creator.

(2) We saw in the last chapter that God was also the Sustainer, as being a factor in the interaction of the Ego and the Deity.

(3) It has been implicitly asserted in our discussions of method in chapters v. and viii., that the Deity must be conceived as an intelligent and personal Spirit. For Cause is a category which is valid only if used by persons and of persons (cp. ch. iii. § 11), while personality is the conception expressive of the highest fact we know (cp. ch. viii. § 18); hence it is only by ascribing personality to God that He can be regarded either as the Cause or as the Perfector of the world-process.1 Lastly, Evolution is meaningless if it is not teleological (cp. ch. vll. §§ 20, 21), and we cannot conceive a purpose except in the intelligence of a personal being. And we are prevented by the principle of not multiplying entities needlessly to invent gratuitous fictions like an impersonal intelligence or unconscious purpose.

It follows (4) that God is finite, or rather that to God, as to all realities, infinite is an unmeaning epithet. This conclusion also has already been foreshadowed in many ways. Thus (a) it followed from Kant's criticism of the proofs of the existence of God, that only a finite God could be inferred from the nature of the world (cp. ch. ii. § 19 s.f). No evidence can prove an infinite cause of the world, for no evidence can prove anything but a cause adequate to the production of the world, but not infinite. To infer the infinite from the finite is a fallacy like inferring the unknowable from the known, and all arguments in favour of an infinite God must commit it. We argue with finite minds from finite data, and our conclusions must be of a like nature. (b) It follows from the conception of God as Force (cp. ch. ix. § 21); for Force implies resistance, and if God is to enforce His will upon the world. He cannot just for that reason, be all — unless indeed He is by some inexplicable chance divided against Himself. And so, too (c), just because God is a factor in all things, He cannot be all things. For to interact implies a not-God to react upon God. Lastly (a), finiteness follows from the whole account given in the last chapter of the divine economy of the world.

§ 2. But these conclusions conflict sharply with the ordinary doctrines both of theology and of philosophy.

In theology we are wont to hear God called the infinite, omnipotent, Creator of all things, while in philosophy we hear of the all-embracing Absolute and infinite, in which all things are and have their being. And as this conflict can be no longer dissembled or postponed, we must now either make good our defiance of the united forces of theology and philosophy, or be crushed by the overwhelming weight of their authority. In so unequal a contest our only hope lies in the divisions and hesitations of our adversaries. For it may be that their agreement is not so perfect as we had feared, that the bearing of some of their chief objections is ambiguous, and that with a little skill we can find efficient support in the very citadels of our opponents. Hence we must aim at reconciling to the novelty of our views all but the most hopelessly prejudiced, and seek to address appeals to them to which they cannot but listen. In dealing with philosophy we may appeal to reason, in dealing with religion to feeling, and in dealing with theology, which has not hitherto always shown itself very susceptible either to reason or to feeling, to its own interests. Thus we shall show to the first that the rational grounds for the assumption of an infinite existence are mistaken and absurd, to the second, that its emotional consequences are atrocious and destructive of all religious feeling, and to the third, that it is this doctrine which has been the fatal canker that produced the chronic debility of faith, and the real obstacle to the practical supremacy of religion.§ 3. In pursuance of our practice of starting from the apparently simple and intelligible, but really so confused, conceptions of ordinary thought, we shall examine first the religious conception of God. In the course of that examination it will soon appear that it is a self-contradictory jumble of inconsistent elements, of which those which are practically the most important imply the finiteness of the Deity, and tend in the direction of the doctrine we have propounded, while the others, which are theoretically more prominent, but might be with great advantage dispensed with in practical religion, would, if carried out consistently, result in philosophic atheism.

And not only is the combination of human and infinite elements in the conception of God an outrage upon the human reason, but it leads to no less outrageous consequences from the point of view of human feeling. For by ascribing unlimited power to God, it makes God the author of all evil, and imprisons us in a Hell to escape from which would be rebellion against omnipotence. To be brief, the attribute of infinity contradicts and neutralizes all the other attributes of God, and makes it impossible to ascribe to the Deity either personality, or consciousness, or power, or intelligence, or wisdom, or goodness, or purpose or object in creating the world; an infinite Deity does not effect a single one of the functions which the religious consciousness demands of its God.

It is easy to show that every one of the religious attributes must be excluded from an infinite Deity. Thus an infinite God can have neither personality nor consciousness, for they both depend on limitation. Personality rests on the distinction of one person from another, consciousness on the distinction of Self and Not-Self.2 An all-embracing person, therefore, is an utterly unmeaning phrase, and if it meant anything, it would mean something utterly subversive of all religion. For the infinite personality would equally embrace and impartially absorb the personalities of all finite individuals, and so Jesus and Barabbas would be revealed as co-existent, and therefore as co-equal incarnations of an infinite God.

The phrase infinite power is, as has been stated (§ 1), equally meaningless. Not only is power a finite conception, applicable only to a finite world in which force implies resistance, but when used out of its setting it becomes a contradiction. Power is power only if it overpowers what resists, and it is not infinite if anything resists it. Infinite power, therefore, is as unmeaning as a round square.

Neither can intelligence or wisdom be ascribed to an infinite God. For such a God could have neither personality nor consciousness, his intelligence would have to be impersonal and his wisdom unconscious, and to such terms our minds can give no meaning. And moreover, what we understand by wisdom is an essentially finite quality, shown in the adaptation of means to ends. But the infinite can neither have ends nor require means to attain them.

§ 4. Goodness, again, is doubly impossible as an attribute of an infinite God; in the first place, because to him all things are good, and in the second, because the distinction of good and evil must be entirely unmeaning. To put the difficulty in its homeliest form, God cannot be both all-good and all-powerful, in a world in which evil is a reality. For if God is all-powerful everything must be exactly what it should be, from God's point of view, else He would instantly alter it. If, then, evil things exist, it must be because God wills to have it so, i.e., because God is, from our point of view, evil. Or conversely, if God is good, He must put up with the continuance of evil because He cannot remove it. This is the 'terrible mystery of evil' which for 2,000 years has been a stumbling-block to all practical religion, tried the faith of all believers, and depressed and debased all thought on the ultimate questions of life, and is as 'insoluble a mystery' to theologians now as it was in the beginning. And it is perhaps likely to remain so, seeing that, as Goethe says, "a complete contradiction is alike mysterious to wise men and to fools," and that no labour can ever extract any sense out of a gratuitous combination of incoherent words.

Hence it is not surprising that no attempt at reconciling the divine goodness with divine power has ever been successful; indeed, the only way in which they have ever appeared to be successful was either by covertly limiting the divine power, or by misusing the term goodness in some non-human sense, to denote a quality shown in God's action towards imaginary beings other than man.

Thus Leibnitz's famous Theodicy, e.g., depends on a limitation of God. For to show that the world is the best of all possible worlds is to imply that not all worlds were possible, so that the best possible did not turn out a perfect one.

So, again, to say that God created the world because it was good, is to limit God by the preexistence of a good and evil independent of divine enactment.

Nor, again, can the responsibility for evil be shifted to the Devil or the perversity due to human Free-will, unless these powers really limit the divine omnipotence. For if we or the Devil are permitted to do evil while God is able to prevent or destroy us, the real responsibility rests with God.On the other hand, the commonplace suggestion that, if we could see the whole universe, the good would be seen to predominate immensely, depends on an invalid use of goodness out of relation to man. For "what care I how good he be, if he be not good to me?" What does goodness mean to us, if it is not goodness to us? And besides, it does not answer the difficulty; for it is still necessary to ask why God could or would not create a world, which was not only predominantly, but entirely good. It surely does not befit infinite power to neglect even the most infinitesimal section, to overlook even the remotest corner, to fall short of making the whole universe perfect.

But perhaps the most curious interference of human limitations with the course of superhuman action is shown in the argument which sets down evil to the imperfection of Law. It is supposed that by a series of miracles all things might have been made perfect, but that this would have been inconsistent with the divine determination to conduct the world according to natural laws. Thus evil is the price paid for 'the reign of Law,' for which we have in modern times developed a good deal of superstitious reverence. But the plausibility of the argument depends upon a wholly unwarranted analogy with human law. It is true that human laws cannot avoid the commission of a certain amount of injustice, because law is general, and cannot be made to fit the requirements of particular cases.

But how can we argue from the impotence of limited beings to the powers of omnipotence? How can we suppose the divine intelligence incapable of devising, or the divine omnipotence incapable of executing, laws, which should not fail to be just in every case, to be absolutely good always and under all circumstances? The argument surely forgets that the laws of nature are ex hypothesi the outcome of absolute legislative power directed by absolute wisdom, and might surely have been so enacted as to work with perfect smoothness. And even if the universality of law were incompatible with perfection, why should not perfect goodness have been secured by a series of miraculous interventions? How should we have been the wiser or the worse? Would not such a series have ipso facto become the legitimate order of things? And how could even the most fastidious taste have objected to a deus ex machina, when no other procedure was known? What then can have prompted the preference of law with its imperfection? Shall it be said that it was preferred as demanding less exertion of the divine power? But it is both unprofitable and repugnant to exhaust the resources of unworthy human analogies in order to reject one after another the foolish palliatives of an insoluble contradiction.

§ 5. The simple truth is that the human distinctions of good and evil have no application to an infinite Deity. We must admit that either all things are good, or that God himself is evil; but in either case the value of the human distinction is destroyed. From the standpoint of an infinite Deity, on the other hand, all things must be good, for they depend absolutely on his will, and it is his will that all things should be what they are. God alone is responsible for all that happens, and every action is wholly God's and wholly good. And yet a true instinct tells us that the distinction of good and evil is a vital one, that things are not perfect, that Evil is as real as Good, as real as life, as real as we are, as real as our whole world and its process, and that it can be explained away only at the cost of dissolving the world into a baseless dream.

Yet this is precisely what this unhappy dogma of the infinity of God leads to; it denies the reality of evil, because it denies the reality and destroys the rationality of the whole world. So long as we deal with finite factors, the function of pain and the nature of Evil can be more or less understood, but as soon as it is supposed to display the working of an infinite power, everything becomes wholly unintelligible. We can no longer console ourselves with the hope that "good becomes the final goal of ill," we can no longer fancy that imperfection serves any secondary purpose in the economy of the universe. A process by which evil becomes good is unintelligible as the action of a truly infinite power which can attain its end without a process; it is absurd to ascribe imperfection as a secondary result to a power which can attain all its aims without evil. Hence the world-process, and the intelligent purpose we fancy we detect in it, must be illusory, in precisely the same way and for precisely the same reason, as evil. God can have no purpose, and the world cannot be in process. For a purpose and process both imply limitation. To adapt means to ends implies that the ends cannot be achieved without them; to attain aims by a process implies that they cannot be reached instantaneously. An infinite power, therefore, can have no need of means to attain its ends, no need of a process whereby to evolve the world, no need of evil as a means to good. It requires no means, and hence the ''means" it uses can have no meaning. The world becomes an unintelligible freak of irresponsible insanity. If the world is the product of an infinite power, it is utterly unknowable, because its process and its nature would be alike unnecessary and unaccountable.

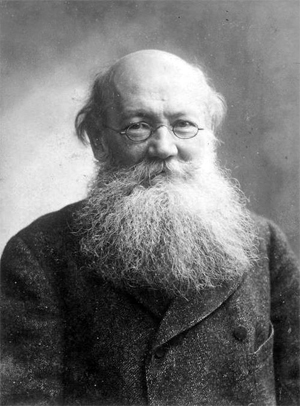

Thus the attribute of infinity, so far from exalting the Deity, would rather make him into a devil, careless of, and even rejoicing in, evil and misery, infinitely worse than the Devil of tradition, because armed with omnipotence, and, in view of the impossibility of admitting the independence of the Finite, also infinitely more unaccountable, inasmuch as in inflicting misery on the world, he would after all only be lacerating himself.-- Riddles of the Sphinx: A Study in the Philosophy of Evolution, by A TROGLODYTE [Ferdinand Canning Scott Schiller]

Moreover, the Whiteheadian doctrine of three ultimates—the one supreme being or God, the many finite beings or the cosmos, and being itself or creativity—also implies a religious pluralism that holds that

the different kinds of religious experience are (not experiences of the same ultimate reality, but) diverse modes of experiencing diverse ultimate aspects of the totality of reality. For example:

One of these [three ultimates], corresponding with what Whitehead calls “creativity”, has been called “Emptiness” (“Sunyata”) or “Dharmakaya” by Buddhists, “Nirguna Brahman” by Advaita Vedantists, “the Godhead” by Meister Eckhart, and “Being Itself” by Heidegger and Tillich (among others). It is the formless ultimate reality. The other ultimate, corresponding with what Whitehead calls “God”, is not Being Itself but the Supreme Being. It is in-formed and the source of forms (such as truth, beauty, and justice). It has been called “Amida Buddha”, “Sambhogakaya”, “Saguna Brahman”, “Ishvara”, “Yaweh”, “Christ”, and “Allah”. (D. Griffin 2005: 47)

[Some] forms of Taoism and many primal religions, including Native American religions […] regard the cosmos as sacred. By recognizing the cosmos as a third ultimate, we are able to see that these cosmic religions are also oriented toward something truly ultimate in the nature of things. (D. Griffin 2005: 49)

The religious pluralism implication of Whitehead’s doctrine of three ultimates has been drawn most clearly by John Cobb. In “John Cobb’s Whiteheadian Complementary Pluralism”, David Griffin writes:

Cobb’s view that the totality of reality contains three ultimates, along with the recognition that a particular tradition could concentrate on one, two, or even all three of them, gives us a basis for understanding a wide variety of religious experiences as genuine responses to something that is really there to be experienced. “When we understand global religious experience and thought in this way”, Cobb emphasizes, “it is easier to view the contributions of diverse traditions as complementary”. (D. Griffin 2005: 51)

8. Whitehead’s InfluenceWhitehead’s key philosophical concept—the internal relatedness of occasions of experience—distanced him from the idols of logical positivism. Indeed, his reliance on our intuition of the extensive relatedness of events (and hence, of the space-time metric) was at variance with both Poincaré’s conventionalism and Einstein’s interpretation of relativity: his reliance on our intuition of the causal relatedness of events, and of both the efficient and the final aspects of causation, was an insult to the anti-metaphysical dogmas of Hume and Russell; his method of causal explanation was also an antipode of

Ernst Mach’s method of economic description; his philosophical affinity with

James and

Bergson as well as his endeavor to harmonize science and religion made him liable to the Russellian charge of anti-intellectualism; and his genuine modesty and aversion to public controversy made him invisible at the philosophical firmament dominated by the brilliance of Ludwig Wittgenstein.

At first—because of Whitehead’s Principia Mathematica collaboration with Russell as well as his application of mathematical logic to abstract the basic concepts of physics—logical positivists and analytic philosophers admired Whitehead. But when Whitehead published Science and the Modern World, the difference between Whitehead’s thought and theirs became obvious, and they grew progressively more dissatisfied over the direction in which Whitehead was moving. Susan Stebbing of the Cambridge school of analysis is only one of many examples that could be evoked here (cf. Chapman 2013: 43–49), and in order to find a more positive reception of Whitehead’s philosophical work, one has to turn to opponents of analytic philosophy such as Robin George Collingwood (for example, Collingwood 1945). The differences with logical positivism and analytic philosophy, however, should not lead philosophers to neglect the affinities of Whitehead’s thought with these philosophical currents (cf. Shields 2003, Desmet & Weber 2010, Desmet & Rusu 2012, Riffert 2012).

Despite signs of interest in Whitehead by a number of famous philosophers—for example, Hannah Arendt, Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Gilles Deleuze—

it is fair to say that Whitehead’s process philosophy would most likely have entered oblivion if the Chicago Divinity School and the Claremont School of Theology had not shown a major interest in it. In other words, not philosophers but theologians saved Whitehead’s process philosophy from oblivion. For example, Charles Hartshorne, who taught at the University of Chicago from 1928 to 1955, where he was a dominant intellectual force in the Divinity School, has been instrumental in highlighting the importance of Whitehead’s process philosophy, which dovetailed with his own, largely independently developed thought. Hartshorne wrote:

The century which produced some terrible things produced a scientist scarcely second in genius and character to any that ever lived, Einstein, and a philosopher who, I incline to say, is similarly second to none, unless it be Plato. To make no use of genius of this order is hardly wise; for it is indeed a rarity. A mathematician sensitive to so many of the values in our culture, so imaginative and inventive in his thinking, so eager to learn from the great minds of the past and the present, so free from any narrow partisanship, religious or irreligious, is one person in hundreds of millions. He can be mistaken, but even his mistakes may be more instructive than most other writers’ truth. (2010: 30)

After mentioning a number of other theologians next to Hartshorne as part of “the first wave of … impressive Whitehead-inspired scholars”, Michel Weber—in his Introduction to the two-volume Handbook of Whiteheadian Process Thought—writes:

In the sixties emerged John B. Cobb, Jr. and Shubert M. Ogden. Cobb’s Christian Natural Theology remains a landmark in the field. The journal Process Studies was created in 1971 by Cobb and Lewis S. Ford;

the Center for Process Studies was established in 1973 by Cobb and David Ray Griffin in Claremont. The result of these developments was that Whiteheadian process scholarship has acquired, and kept, a fair visibility … (Weber & Desmond 2008: 25)

Indeed, inspired mainly by Cobb and Griffin, many other centers, societies, associations, projects and conferences of Whiteheadian process scholarship have seen the light of day all over the world—nowadays most prominently in the People’s Republic of China (cf. Weber & Desmond 2008: 26–30). In fact, Weber himself has created in 2001 the Whitehead Psychology Nexus and the Chromatiques whiteheadiennes scholarly societies, and he has been the driving force behind several book series, one of which—the Process Thought Series—includes the already mentioned Handbook of Whiteheadian Process Thought, in which 101 internationally renowned Whitehead scholars give an impressive overview of the 2008 status of their research findings in an enormous variety of domains (cf. The Centre for Philosophical Practice [Other Internet Resources, OIR] and Armour 2010). Missing in the Handbook, however, are most Whitehead scholars reading Whitehead through Deleuzian glasses—especially Isabelle Stengers, whose 2011 book, Thinking with Whitehead, cannot be ignored. The Lure of Whitehead, edited by Nicholas Gaskill and A. J. Nocek in 2014, can largely remedy that shortcoming. Important for Whitehead scholarship, next to the many book series initiated by Weber, are the older SUNY Series in Constructive Postmodern Thought, the recent Contemporary Whitehead Studies and the Critical Edition of Whitehead (cf. Whitehead Research Project [OIR]) as well as the new Toward Ecological Civilization Series (cf. Process Century Press [OIR]). In the Series Preface of the latter series, John Cobb writes:

We live in the ending of an age. But the ending of the modern period differs from the ending of previous periods, such as the classical or the medieval. The amazing achievements of modernity make it possible, even likely, that its end will also be the end of civilization, of many species, or even of the human species. At the same time, we are living in an age of new beginnings that give promise of an ecological civilization. Its emergence is marked by a growing sense of urgency and deepening awareness that the changes must go to the roots of what has led to the current threat of catastrophe.

In June 2015, the 10th Whitehead International Conference was held in Claremont, CA. Called “Seizing an Alternative: Toward an Ecological Civilization”, it claimed an organic, relational, integrated, nondual, and processive conceptuality is needed, and that Alfred North Whitehead provides this in a remarkably comprehensive and rigorous way. We proposed that he could be “the philosopher of ecological civilization”. With the help of those who have come to an ecological vision in other ways, the conference explored this Whiteheadian alternative, showing how it can provide the shared vision so urgently needed.

Cobb refers to the tenth of the bi-annual International Whitehead Conferences, which are sponsored by the International Process Network. The International Whitehead Conference has been held at locations around the globe since 1981. This is an important venture in global Whiteheadian thought, as key Whiteheadian scholars from a variety of disciplines and countries come together for the continued pursuit of critically engaging a process worldview.

Bibliography

Primary Literature1898, A Treatise on Universal Algebra with Applications, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Whitehead 1898 available online]

1902, “On Cardinal Numbers”, American Journal of Mathematics, 24(4): 367–394. doi:10.2307/2370026

1906a, “On Mathematical Concepts of the Material World”, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series A, 205(387–401):465–525. doi:10.1098/rsta.1906.0014

1906b, The Axioms of Projective Geometry, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Whitehead 1906b available online]

1907, The Axioms of Descriptive Geometry, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Whitehead 1907 available online]

1910a, “The Philosophy of Mathematics”, Science Progress in the Twentieth Century, 5: 234–239. [Whitehead 1910a available online]

1910b, 1912, 1913 (with Bertrand Russell), Principia Mathematica, 3 volumes, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

1911 [1958], An Introduction to Mathematics, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1958. [Whitehead 1911 available online]

1916, “La théorie relationniste de l’espace”, Revue de Métaphysique et Morale, 23(3): 423–454.

1917 [1974], The Organisation of Thought: Educational and Scientific, London: Williams and Norgate. Reprinted Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1974. [Whitehead 1917 available online]

1919a [1982], An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Natural Knowledge, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Reprinted New York: Dover Publications, 1982. [Whitehead 1919a available online]

1919b, “A Revolution of Science”, The Nation (London), November 15, 26: 232–233.

1920 [1986], The Concept of Nature, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Whitehead 1920 available online]

1922 [2004], The Principle of Relativity with Applications to Physical Science, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Reprinted New York: Dover Publications, 2004. [Whitehead 1922 available online]

1926a [1967], Science and the Modern World, (Lowell Institute Lectures 1925), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Reprinted New York: The Free Press, 1967. [Whitehead 1926a available online]

1926b [1996], Religion in the Making, (Lowell Institute Lectures 1926), New York: The Macmillan Company. Reprinted New York: Fordham University Press, 1996.

1927 [1985], Symbolism: Its Meaning and Effect, New York: Macmillan. Reprinted New York: Fordham University Press, 1985.

1929a, The Aims of Education and Other Essays, New York: The Macmillan Company.

1929b [1958], The Function of Reason, Princeton: Princeton University Press. Reprinted Boston: Beacon Press, 1958.

1929c [1985], Process and Reality, (Gifford Lectures 1927–28), New York: Macmillan. Corrected edition, David Ray Griffin & Donald W. Sherburne (eds.), New York: The Free Press, 1985.

1933 [1967], Adventures of Ideas, New York: Macmillan Company. Reprinted New York: The Free Press, 1967.

1934 [2011], Nature and Life, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Reprinted Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

1938 [1968], Modes of Thought, New York: Macmillan Company. Reprinted New York: The Free Press, 1968.

1947 [1968], Essays in Science and Philosophy, New York: Philosophical Library. Reprinted Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1968.

1954 [1977], Dialogues of Alfred North Whitehead, Lucien Price (ed.), Boston: Little Brown. Reprinted Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

1961, The Interpretation of Science, Selected Essays, A. H. Johnson, (ed.), New York: Bobbs-Merrill.

2017, The Harvard Lectures of Alfred North Whitehead 1924–1925: Philosophical Presupositions of Science, (The Edinburgh Critical Edition of the Complete Works of Alfred North Whitehead), Paul Bogaard & Jason Bell (eds.), Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Secondary LiteratureArmour Lesley, 2010, “Looking for Whitehead”, British Journal for the History of Philosophy, 18(5): 925–939. doi:10.1080/09608788.2010.524768

Athern, Daniel, 2011, “Physics and Whitehead: An Alternative Approach”, Process Studies, 40(1): 80–90. doi:10.5840/process20114014

Basile, Pierfrancesco, 2009, Leibniz, Whitehead and the Metaphysics of Causation, London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9780230242197

Bostock, David, 2010, “Whitehead and Russell on Points”, Philosophia Mathematica, 18(1): 1–52. doi:10.1093/philmat/nkp017

Bright, Laurence, 1958, Whitehead’s Philosophy of Physics, London: Sheed and Ward.

Chapman, Siobhan, 2013, Susan Stebbing and the Language of Common Sense, London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9781137313102

Clark, G. L., 1954, “The Problem of Two Bodies in Whitehead’s Theory”, Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Series A (Mathematics & Physics) 64(1): 49–56. doi:10.1017/S0080454100007317

Cobb, John B., 2007, A Christian Natural Theology: Based on the Thought of Alfred North Whitehead, second edition, Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press. First edition 1965.

–––, 2015, Whitehead Word Book: A Glossary with Alphabetic Index to Technical Terms in Process and Reality, Anoka, MN: Process Century Press.

Code, Murray, 1985, Order & Organicism, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Collingwood, Robin George, 1945, The Idea of Nature, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Connelly, R. J., 1981, Whitehead vs Hartshorne: Basic Metaphysical Issues, Washington, DC: University Press of America.

Deroo, Emeline & Bruno Leclerc (eds.), 2011, Special Issue on Whitehead’s Early Work, Logique et Analyse, Nouvelle Série, 54(214).

Desmet, Ronny, 2010, “Principia Mathematica Centenary”, Process Studies, 39(2): 225–263. doi:10.5840/process201039223

–––, 2011, “Putting Whitehead’s theory of gravitation in its historical context”, Logique et Analyse, Nouvelle Série, 54(214): 287–315.

–––, 2016a, “Poincaré and Whitehead on Intuition and Logic in Mathematics”, Process Studies Supplements, Issue 22: 1–61.

–––, 2016b, “Out of Season: Evaluating Whitehead’s alternative theory of gravitation by means of the aesthetic criteria induced by Einstein’s general theory of relativity”, Process Studies Supplements, Issue 23: 1–140.

–––, 2016c, “Aesthetic Comparison of Einstein’s and Whitehead’s Theories of Gravity”, Process Studies, 45(1): 33–46. doi:10.5840/process20164512

––– (ed.), 2016d, Intuition in Mathematics and Physics: A Whiteheadian Approach, Anoka, MN: Process Century Press.

Desmet, Ronny & Bogdan Rusu, 2012, “Whitehead, Russell, and Moore: Three Analytic Philosophers”, Process Studies, 41(2): 214–234. doi:10.5840/process201241231

Desmet, Ronny & Michel Weber (eds.), 2010, Whitehead: The Algebra of Metaphysics, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium: Les Editions Chromatika.

Eastman, Timothy & Hank Keeton (eds.), 2004, Physics and Whitehead: Quantum, Process and Experience, Albany, NY: State Univeristy of New York Press.

Eastman, Timothy & Epperson, Michael & Griffin, David Ray (eds.), 2016, Physics and Speculative Philosophy: Potentiality in Modern Science, Berlin: de Gruyter.

Eddington, Arthur, 1918 [2006], Report on the Relativity Theory of Gravitation, London: Fleetway Press. Reprinted New York: Dover Publications, 2006. [Eddington 1918 available online]

–––, 1924, “Comparison of Whitehead’s and Einstein’s Formulae”, Nature, 113(2832): 192. doi:10.1038/113192a0

Eisendrath, Craig, 1971, The Unifying Moment: The Psychological Philosophy of William James and Alfred North Whitehead, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Emmet, Dorothy, 1932, Whitehead’s Philosophy of Organism, London: Macmillan.

Epperson, Michael, 2004, Quantum Mechanics and the Philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead, New York: Fordham University Press.

Epperson, Michael & Elias Zafiris, 2013, Foundations of Relational Realism, Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Fitzgerald, Janet, 1979, Alfred North Whitehead’s Early Philosophy of Space and Time, Washington. DC: University Press of America.

Ford, Lewis, 1984, The Emergence of Whitehead’s Metaphysics: 1925–1929, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Franklin, Stephen T., 1990, Speaking from the Depths, Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

Gandon, Sébastien, 2012, Russell’s Unknown Logicism: A Study in the History and Philosophy of Mathematics, London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9781137024657

Gaskill, Nicholas & A.J. Nocek (eds.), 2014, The Lure of Whitehead, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Gibbons, Gary & Clifford M. Will, 2008, “On the Multiple Deaths of Whitehead’s Theory of Gravity”, Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 39(1): 41–61. doi:10.1016/j.shpsb.2007.04.004

Gould, Stephen Jay, 1997, “Nonoverlapping Magisteria”, Natural History, 106(March): 16–22. [Gould 1997 available online]

Grattan-Guinness, Ivor, 1991, “Russell and G.H. Hardy: A Study of Their Relationship”, Journal of the Bertrand Russell Archives, 11(2): 165–79. doi:10.15173/russell.v11i2.1806

–––, 2000, The Search for Mathematical Roots, 1870–1940, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

–––, 2002, “Algebras, Projective Geometry, Mathematical Logic, and Constructing the World: Intersections in the Philosophy of Mathematics of A. N. Whitehead”, Historia Mathematica, 29(4): 427–462. doi:10.1006/hmat.2002.2356

Griffin, David Ray (ed.), 2005, Deep Religious Pluralism, Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press.

–––, 2007, Whitehead’s Radically Different Postmodern Philosophy, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Griffin, Nicholas & Bernard Linsky (eds.), 2013, Principia Mathematica at 100, Hamilton, ON: Bertrand Russell Research Center.

Griffin, Nicholas, Bernard Linsky & Kenneth Blackwell (eds.), 2011, The Palgrave Centenary Companion to Principia Mathematica, London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9781137344632

Hammerschmidt, William, 1947, Whitehead’s Philosophy of Time, New York: King’s Crown Press.

Hartshorne, Charles, 1972, Whitehead’s Philosophy: Selected Essays, 1935–1970, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

–––, 2010, “Whitehead in Historical Context”, in Charles Hartshorne & W. Creighton Peden, Whitehead’s View of Reality, UK: Cambrige Scholar Publishing, 7–30.

Hättich, Frank, 2004, Quantum Processes: A Whiteheadian Interpretation of Quantum Field Theory, Münster: Agenda Verlag.

Henning, Brian, Adam Scarfe & Dorian Sagan (eds.), 2013, Beyond Mechanism, Lanham: Lexington Books.

Herstein, Gary, 2006, Whitehead and the Measurement Problem of Cosmology, Frankfurt: Ontos Verlag.

Hosinski, Thomas E., 1993, Stubborn Fact and Creative Advance: An Introduction to the Metaphysics of Alfred North Whitehead, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc.

Irvine, A. D. (ed.), 2009, Philosophy of Mathematics, Amsterdam: Elsevier/North Holland.

Jeans, James, 1914, Report on Radiation and the Quantum-Theory, London: “The Electrician” Printing & Publishing Co.

Johnson, A. H., 1952, Whitehead’s Theory of Reality, Boston: Beacon Press.

Jones, Judith, 1998, Intensity: An Essay in Whiteheadian Ontology, Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press.

Kraus, Elizabeth, 1998, The Metaphysics of Experience: A Companion to Whitehead’s Process and Reality, New York: Fordham University Press.

Lango, J. W., 1972, Whitehead’s Ontology, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Lawrence, N. M., 1956, Whitehead’s Philosophical Development, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Leclerc, Ivor, 1958, Whitehead’s Metaphysics: An Introductory Exposition, London: Allen and Unvin; New York: Macmillan.

Lowe, Victor, 1962, Understanding Whitehead, Baltimore: The John Hopkins Press.

–––, 1985, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and His Work, Volume I: 1861–1910, Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press.

–––, 1990, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and His Work; Volume II: 1910–1947, J.B. Schneewind (ed.), Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press.

Lucas, G. R., 1989, The Rehabilitation of Whitehead, Albany, NY: State University of New York, 1989.

Malin, Shimon, 2001, Nature Loves to Hide: Quantum Physics and the Nature of Reality, a Western Perspective, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McHenry, Leemon, 1992, Whitehead and Bradley: A Comparative Analysis, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

–––, 2015, The Event Universe: The Revisionary Metaphysics of Alfred North Whitehead, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Mays, Wolfe, 1959, The Philosophy of Whitehead, London: Allen and Unwin.

–––, 1977, Whitehead’s Philosophy of Science and Metaphysics, The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Mesle, Robert, 2008, Process-Relational Philosophy: An Introduction to Alfred North Whitehead, Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Foundation Press.

Nobo, Jorge Luis, 1986, Whitehead’s Metaphysics of Extension and Solidarity, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Palter, R. M., 1960, Whitehead’s Philosophy of Science, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Plamondon, Ann L., 1979, Whitehead’s Organic Philosophy of Science, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Ramsden Eames, Elizabeth, 1989, Bertrand Russell’s Dialogue with His Contemporaries, Carbondale, IL: South Illinois University Press.

Riffert, Franz, 2012, “Analytic Philosophy, Whitehead, and Theory Construction”, Process Studies, 41(2): 235–260. doi:10.5840/process201241232

Ross, S. D., 1983, Perspective in Whitehead’s Metaphysics, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Rovelli, Carlo, 2017, Reality is not what it seems: The journey to quantum gravity, UK: Penguin Books.

Russell, Bertrand, 1897 [1956], Essay on the Foundations of Geometry, New York: Dover Publications.

–––, 1903, The Principles of Mathematics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

–––, 1948, “Whitehead and Principia Mathematica”, Mind, 57(226): 137–138. doi:10.1093/mind/LVII.226.137

–––, 1956, “Alfred North Whitehead”, in Portraits from Memory, New York: Simon and Schuster, 99–104.

–––, 1959, My Philosophical Development, London: George Allan and Unwin.

–––, 1967, The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell, Volume 1, London: George Allan and Unwin.

Russell, Robert John & Christoph Wassermann, 2004, “A Generalized Whiteheadian Theory of Gravity: The Kerr Solution”, Process Studies Supplement, Issue 6.

Schilpp, Paul (ed.), 1941, The Philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead, La Salle: Open Court.

Segall, Matthew, 2013, Physics of the World-Soul: The Relevance of Alfred North Whitehead’s Philosophy of Organism to Contemporary Scientific Cosmology, UK: Amazon.

Shaviro, Steven, 2009, Without Criteria: Kant, Whitehead, Deleuze, and Aesthetics, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Sherburne, Donald W., 1961, A Whiteheadian Aesthetics, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Shields, G. W. (ed.), 2003, Process and Analysis: Whitehead, Hartshorne, and the Analytic Tradition, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Smith, Raymond, 1953, Whitehead’s Concept of Logic, Westminster: The Newman Press.

Snow, C.P., 1959, The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution, (Rede Lecture, 1959), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stapp, Henry, 1993, Mind, Matter, and Quantum Mechanics, Berlin: Springer Verlag.

–––, 2007, Mindful Universe: Quantum Mechanics and the Participating Observer, Berlin: Springer Verlag.

Stengers, Isabelle, 2011, Thinking with Whitehead, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Synge, J.L., 1952, “Orbits and rays in the gravitational field of a finite sphere according to the theory of A. N. Whitehead”, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series A 211(1106): 303–319. doi:10.1098/rspa.1952.0044

Temple, George, 1924, “Central Orbits in Relativistic Dynamics treated by the Hamilton-Jacobi Method”, Philosophical Magazine, Series 6, 48(284): 277–292. doi:10.1080/14786442408634491

Von Ranke, Oliver, 1997, Whiteheads Relativitätstheorie, Regensburg: Roderer Verlag.

Weber, Michel & Will Desmond (eds.), 2008, Handbook of Whiteheadian Process Thought, 2 volumes, Frankfurt: Ontos Verlag.

Other Internet Resources• International Process Network

• Alfred North Whitehead, MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive.

• Alfred North Whitehead, Mathematics Genealogy Project.

• Alfred North Whitehead, Project Gutenberg.

• Process Studies, a peer-reviewed journal.

• Society for the Study of Process Philosophies.

• Whitehead and Russell’s Principia Mathematica.

• Whitehead Research Project.

• The Centre for Philosophical Practice “Chromatiques whiteheadiennes”

• Process Century Press

• Center for Process Studies

AcknowledgmentsFor the 2018 version, Ronny Desmet has joined Andrew Irvine as co-author and taken the lead in maintaining this entry.