Chapter 4: Black and Time-Stained Rocks

by John Keay

Text copyright © John Keay 1981

Photographs copyright © Colour Library International Ltd. 1981

xxx

Freda Bedi Cont'd (#3)

Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#3)

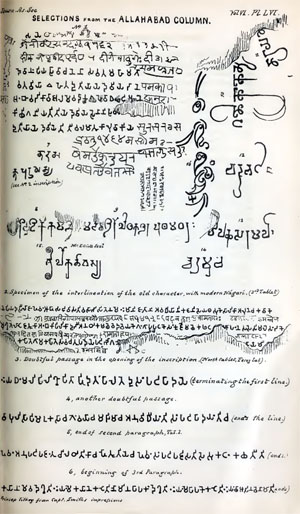

VI.--”Interpretation” Highlights, from "VI.—Interpretation of the most ancient of the inscriptions on the pillar called the lat of Feroz Shah, near Delhi, and of the Allahabad, Radhia [Lauriya-Araraj (Radiah)] and Mattiah [Lauriya-Nandangarh (Mathia)] pillar, or lat, inscriptions which agree therewith."

by James Prinsep, Sec. As. Soc. &c.

1837

"Interpretation" Highlights:

The difficulties with which I have had to contend… the orthography is sadly vitiated [the spelling is spoiled]… the language differs essentially from every existing written idiom… a degree of license is therefore requisite in selecting the Sanskrit equivalent of each word, upon which to base the interpretation — a license dangerous in the use unless restrained within wholesome rules; for a skilful pandit will easily find a word to answer any purpose if allowed to insert a letter or alter a vowel ad libitum…. some substitutions authorized by analogy to the Pali… have for their adoption the only excuse, that nothing better offers…

[F]rom the incompleteness of the lines on the right hand the context cannot thoroughly be explained… We might translate the whole of the first line [x] … and other insulated words can be recognized but without coherence…. The general object of Devanampiya's series of edicts is, according to my reading, to proclaim his renunciation of his former faith, and his adoption of the Buddhist persuasion… He addresses to his disciples, or devotees, (for so I have been obliged to translate rajaka, as the Sanskrit [x], though I would have preferred rajaka, ministers, had the first a been long … the chief drift of the writing seems directed to enhance the merits of the author…

It is a curious fact that… the name of the author of that religion is nowhere distinctly or directly introduced as Buddha, Gotama, Shakya muni, &c…. the expression Sukatam kachhati, which I have supposed to be intended for sugatam gachhati, may be thought to contain one of Buddha's names as Sugato… but the error in spelling makes the reading doubtful… In another place I have rendered a final expression …'shall give praise to Agni' — a deity we are hardly at liberty to pronounce connected with the Buddhist worship…

It is only by the general tenor of the dogmas inculcated, that we can pronounce it to relate to the Buddhist religion…. The sacred name constantly employed…. is Dhamma (or dharma), 'virtue;'… Buddhism was at that time only sectarianism; a dissent from a vast proportion of the existing sophistry and metaphysics of the Brahmanical schools, without an absolute relinquishment of belief in their gods, or of conformity in their usages, and with adherence still to the milder qualities of the religion… The very term Devanampiya, 'beloved of the gods,' shews the retention of the Hindu pantheon generally… The word [dhamma] is here evidently used in its simple sense of "the law, virtue, or religion"… though … there is no worship offered to it, no godhead claimed for it….

The word dhamma is in the document before us generally coupled with another word, vadhi… The most obvious interpretation of the word vadhi is found in the Sanskrit vriddhi, increase… 'the increase of virtue,' 'the expansion of the law,' in allusion to the rapid proselytism which it sought and obtained…. Against this interpretation, if it be urged that the dental dh is in other cases used for the Sanskrit dh, as in the word dharmma itself; in vadha, murder; bandha, bound, &c., such objection may be met by [x]… It is hardly possible to imagine that two expressions so strikingly similar in orthography as dhammavadhi and dhammavatti or vadai, yet of such opposite meaning, should be applied to the same thing. One must be wrong, and I should have had no question which to prefer…

I requested my pandit Kamalakanta to look into … this expression 'wheel of the law'… the actual employment of the term dharma vriddhi was wanting… the pandit met with many instances of the word vriddhi occurring in connection with bodhi, which as applied to the Buddhist faith was nearly synonymous with dharma… the growth of knowledge, or metaphorically the growth of the bodhi or sacred fig tree…. Daya is written taya: idavala, ajavala, and samaguni, samagini: in fact the whole volume is so full of errors of transcription that it was with difficulty Kamalakanta could manage to restore the correct reading…. This passage is corrupt and consequently obscure, but it teaches plainly that dharmavriddhi of our inscription may always be understood, like bodhivridhi, in the general acceptation of 'the Buddhist religion.' Proselytism, turning the wheel, or publishing the doctrines, whichever is preferred, was evidently a main object of the Buddhist system, and it is pointed at continually in the pillar inscription….

[ B]rahmans, the arch-opponents of the faith, are also named, under the disguise of the corrupt spelling babhana… I have said that the founder of the faith is not named. Neither is the ordinary title of the priesthood, bhikhu or bhichhu, to be found…

The words mahamata, (written sometimes mata) and dhamma mahamata, seem used for priests, 'the wise men, the very learned in religion.'… The same epithet is found in conjunction with bhikhu in the interesting passage quoted by Mr. Turnour… But it is possible that this expression has been misunderstood by the pandit… Mr. Hodgson's epitome, above alluded to, gives us another mode of interpretation perhaps more consonant with the spirit of the system… the great mother of Buddha — the universal mother, omniscience, illusion, maya, &c. — and as such may be more correctly supposed to pervade than mahamata the priests…

[T]here is no allusion to the vihara by name, nor to the chaitya, or temple: no hint of images of Buddha's person, nor of relics preserved in costly monuments. The spreading fig tree and the great dhatris, perhaps in memory of those under which his doctrines were delivered, are the only objects to be held sacred…

The edict prohibiting the killing of particular animals is perhaps one of the most curious of the whole…. Many of the names in the list are now unknown, and are perhaps irrecoverable, being the vernacular rather than the classical appellations…. I have pointed out such endeavours as have been made by the pandits to identify them… Others of the names in the enumeration of birds not to be eaten will remind the reader of the injunctions of Moses to the Jews on the same subject. The list in the 11th chapter of Leviticus comprises 'the eagle, the ossifrage, the ospray, the vulture and kite: every raven after his kind, the owl, night hawk, cuckoo and hawk; the little owl, cormorant and great owl: the swan, pelican, and gier-eagle; the stork, heron, lapwing and bat… The verse immediately following the catalogue of birds, "All fowls that creep upon all four shall be an abomination unto you," presents a curious coincidence with the expression of our tablet… which comes after … the tame dove….

But the edict by no means seems to interdict the use of animal food… It restricts the prohibition to particular days of fast… The sheep, goat, and pig seem to have been the staple of animal food at the period… but merit is ascribed to the abstaining from animal food altogether…. Ratna Paula tells me no similar rules are to be found in the Pali works of Ceylon, nor are the particular days set apart for fasting or upavasun in the inscription, exactly in accordance with modern Buddhistic practice… All the days inserted are, however, of great weight in the Hindu calendar of festivals… the two lunar days mentioned in the south tablet, tishya (or pushya) and punarvasu, though now disregarded, are known from the Lalitu Vistara to have been strictly attended to by the early priests… proving that the luni-solar system of the brahmans was the same as we see it now, three centuries before our era, and not the modern invention Bentley and some others have pretended….

(If I have read the passage aright) opposition was contemplated as conversion should proceed… royal benevolence was exercised in a way to conciliate the Nanapasandas, the Gentiles of every persuasion, by the planting of trees along the roadsides, by the digging of wells, by the establishment of bazars and serais, at convenient distances. Where are they all? On what road are we now to search for these venerable relics… [that] would enable us to confirm the assumed date of our monuments? The lat of Feroz is the only one which alludes to this circumstance, and we know not whence that was taken to be set up in its present situation by the emperor Feroz in the 14th century… This cannot be determined without a careful re-examination of the ruinous building surrounding the pillar… The chambers described by Captain Hoare as a menagerie and aviary may have been so adapted from their original purpose as cells for the monastic priesthood… The difficulties and probably cost of its transport, which, judging from the inability of the present Government to afford the expense even of setting the Allahabad pillar upright on its pedestal, must have fallen heavily on the coffers of the Ceylon monarch!...

The Allahabad version is cut off after the 3 first letters of the 19th line… The Mathia and Radhia lats contain it entire, adding only iti at the conclusion, and after Sache Sochaye in the 12th line…. The second part of the Allahabad inscription begins to be legible at the 12th letter of the 14th line. The whole is to be found on the Radhia pillar… The termination at Mathia differs in having inserted after the 3rd letter of the 20th line the words [x]… The word Ajakanani at the end of the 7th line seems accidently to have been omitted in the Feroz lat. It is supplied from the Radhia and Mathia pillars. The Allahabad version is erased from the 3rd letter of the 6th line…. The Mathia and Radhia inscriptions terminate with the tenth line. The remainder of this inscription and the following running round the Column are peculiar to the Delhi monument….

Translation of the Inscription of the North compartment….

The whole of the northern tablet, although composed of words individually easy of translation, presents more difficulties in a way of a satisfactory interpretation than any of the others. This first sentence particularly was unintelligible to Ratna Paula, who for Dusampati would have substituted Dasabala, 'the tea (elephant) powered,' a name of Buddha. The pandit's reading seems more to the purpose… The sense of this passage, although at first sight obvious enough, recedes as the construction is grammatically examined. I originally supposed that Annata was meant for Ananta, the anuswara being placed by accident on the left, and had adopted the nearest literal approach to the text in Sanskrit for the translation… but in this it was necessary to omit two long vowels, in parikhaya and sususaya to place them in the third case. By making them of the fifth case, (in Sanskrit the nyabalope panchami), and by reading Anyata, every letter can be exactly preserved with the sense given in the present translation… the most doubtful words are usritena and chaksho; the latter Ratna Paula would break into cha-kho, 'and certainly' (kho for khalu); the former may be replaced by 'by perseverance,' but this is hardly an improvement. It is also a question whether Dhamma kama is to be applied in a good sense as 'intense desire of virtue,' or in a bad, as 'dominion of the sensual passions.'… This sentence is equally simple in appearance, though ambiguous in meaning from the same cause; kamata is however here applied in the good sense with dharma…. Either 'having obtained devout meditation,' or, which is nearer the text [x], from 'abstinence from passion,' the participle termination twa from the prefixing of pra, becomes yap, or is changed to [x]… mahamata, supremely wise, may be made nearer to the text, where the third a is long, by reading mahamatra, being the holiest act of brahmanical reverence, accompanied by the closing of every corporeal orifice… This passage is somewhat obscure, but it is tolerably made out by attention to the cases of the pronouns and the four times repeated Dharma in the third case… but the aspirated d and the separation of ya would favor the reading, 'this is the true path, or rule,' &c. In either case there are errors in the genders of the pronouns…. Apasinavai… alluding either to the words [x], or the non-omission of deeds just mentioned, or to what follows…. But I prefer the more simple acts, in the neuter like the preceding kiyam: the Sanskrit kriya is however feminine…. [x] may also be read, of the same signification, purity from passion or vice. Chakhuradan is explained in Wilson's Dictionary as 'the ceremony of anointing the eyes of the image at the time of consecration', but it is also allegorically used for any instruction, or opening of the eyes derived from a spiritual teacher…. A very easy sentence; the construction is as that of the Latin ablative absolute, 'many kindnesses being done of me, towards the poor,' &c…. This is also equally clear: aprana may here allude to vegetable life, or to that which doth not draw breath; benevolence to inanimate things. For [x] also grain, food, may be intended. A better sense for apana may be obtained by reading pleasing and conciliatory demeanour…. If ye and se are here preferred, the verbs must be plural, otherwise ya and sa are required. In this, the only method of reading the text, there is a corrupt substitution of k for g twice: but other instances of the same substitution occur elsewhere…. In the translation I have supposed iyam to be ayam, in the neuter, and have taken dekhati, as allied to the vernacular dekhna, which in Sanskrit changes in this tense to drishyate or, is seen…. this is called Asinava, a word of unknown meaning. The pandits would read adinava, transgressions, but the word is repeated more than once with the same spelling, and must therefore be retained…. An obscure passage, chakho (written chukho) being neuter does not agree with esa m., overruling this as an error, we may make dekhiya, is precisely the modern Hindi subjunctive, 'may or shall it see.'… The ti does not exist on the Feroz lat though it is retained on the others. Asinava gamini is the former unknown term, which seems here to mean the nine asa or petty offences…. Some of these agree with the nine kinds of subordinate crimes enumerated in Sanscrit works, which are as follows: ignorance, deceit, envy, inebriety, lust, hypocrisy, hate, covetousness, and avarice….

Translation of the West inscription….

Had the a been long the preferable reading would have been rajaka, assemblies of princes or rulers, quasi courtiers or rulers…. [x] is the pandit’s reading, making rajaka in the vocative, 'oh devotees who are come in many souls, in hundreds of thousands of people', but in this reading janasi, which is found alike in all the texts, must be placed in the 7th case plural, … (Pali janasi ayata), 'having come into this knowledge', is, I think, preferable, and is accordingly adopted…. If the i be long, the word would signify, 'without fear, fearless.'… 'circumambulations must be practised', or 'pious acts,' will be closer to the original. To the termination evu the other lats add ti in this and the following instances. The former agrees with the vernacular hove, 'let be,' the latter with the Sanskrit 'is to be.'… 'shall they become prosperous or unfortunate,' according to the pandit; but a nearer approach to the construction of the text may be formed, 'shall know good or bad fortune.'… It is best to regard [x] as a compound of dharma and ayatam, length, endurance, — or (from ayat), 'the coming.' The word viyo is unknown to either the Sanskrit or the Pali scholar, they suppose it to be a term of applause attached to 'they shall say,' as in the modern Hindvi tumko bhala kahengi, they shall say 'well' to you, they shall applaud you. To praise, may be the root of the expression. It also something resembles the Io of the Greeks, which however like eheu, is used as an expression of lamentation, and this meaning accords also with the word viyo in Clough's Singhalese Dictionary. — Viyo, viyov, viyoga, 'lamentation, separation, absence.' Viyo-dhamma is translated 'perishable things' by Mr. Turnour in a passage from the Pitakattayan… perhaps the 'some little' given of the inhabitants of the village, and preserved shall be on account of worship,' (or they shall give trifling presents to make puja?)… This passage is rather obscure in its application to the preceding; the pandit reads 'the devotees also speak,' but the letter p is uncertain, and I would prefer, ‘shall receive, and having proceeded my devotees shall obtain the sacred offering of chandan’; [x] being read by the pandit as sandal-wood, an unctuous preparation of which is applied to the forehead in pujas, but the aspirated ch makes this interpretation dubious: chhandani are solitary private (occupations) or desires…. An unknown letter in the word chayanti or chapanti leaves this sentence in the same uncertainty. Adopting the former we have, 'by which my devotees (may) accumulate for the purpose of the worship, to pay the expenses of the worship from the accumulated nazars and offerings.'… A new subject here commences, 'moreover let my people frequent the great myrobalan trees (which also the Hindus prize very highly and desire to die under) in the night.' Thus reads the pandit, but the last word is [x], not yatu; and it may be an adverb implying, 'occasionally', or prohibiting altogether. Viyataye may also mean 'for the learned,' viyata in Pali being a scholar, in which case I should understand [x] as the name of some third tree (like the nyctanthes tristis or the white water-lily which opens its petals (or smiles at night) so as to connect the dhatri with the asvattha, or holy fig-tree, thus, 'the dhatri, nisijati and asvatha shall be for the learned.'… The same expression here recurs: 'my people accumulates (or plants?) the auspicious, or the great myrobalan'; perhaps 'caresses' is to be preferred in both places…. A new enjoinder, [x] or, following the Bakra and Mathia texts, may mean, 'the pleasure of drink (vinous liquor) is to be eschewed,’ but for this sense the words should be inverted, as [x]. The exact translation as it stands is, 'pleasure, as wine must be abandoned,' a common native turn of expression, — 'do this (as soon) take poison.'… A curiously introduced parenthesis, 'much to be desired is such glory!’... something is wanting to make the next word intelligible, avaite, &c., as if 'but they shall not be put to death by me.'… 'of men deserving of imprisonment or execution, pilgrimage (is) the punishment (awarded)?' This, the only interpretation consonant with the scrupulous care of life among the Buddhists, is supported by the genitive case of munisanam, yet a closer adherence to the letter of the text may be found in 'the adjudged punishment.' If by [x] pilgrimage be intended, 'banishment,' there is no such disproportion being the punishment awarded as might be at first supposed. It is in the eyes of natives the heaviest infliction…. The general meaning of this sentence can easily be gathered, but its construction is in some parts doubtful, the words [x] follow the same idiom as above, the three days of (or for) the highway robbers or murderers; my, generally placed before the verb or participle (as me kate passim) inclines me to read yote as [x] or [x], though usually written vute … Dine natikavakani is transcribed by the pandit 'among the poor people, blasphemies, or atheistical words,' but this does not connect with the next word ni ripayihanti, where we recognize the 3rd plural of the future tense of root to hurt or injure with the prohibitive ‘not’ prefixed. Perhaps it should be understood 'neither among the poor or the rich shall any whatever (criminals) be tortured (or maimed).' … Here are two other propositions coupled together; tanam I think should be beating, and destroying; jivitayetaram might thus be cruelty to living things. But I adopt this correction only because I see not how otherwise sense can be made…. [x] must be the vernacular corruption of 'they shall pay a fine, or give an alms.'… A doubtful passage for which I venture thus: 'It is my desire thus that the cherishing of these workers of opposition shall be for the (benefit) of the worship,' meaning that the fines shall be brought to credit in the vihara treasury?... The wind-up is almost pure Sanskrit …

Translation of the Inscription on the Southern compartment….

The words iyam dhamma lipi likhapita are here to be understood; otherwise the abstaining from animal food, and the preservation of animal life prescribed below must be limited to the year specified, and must be regarded as an edict of penance obligatory on the prince himself for that particular period…. In Sanskrit this sentence will run [x]. The Radhia and Mathia versions have avadhyani, the y being subjoined… the last is not to be found in dictionaries, but I render it 'owl,' on the authority of Kamalakant, who says rightly that this bird may alone challenge the title of bull-faced!… The nearest Sanskrit ornithological synonyme to gera a is the giddh or vulture, which I have accordingly adopted…. Amba kapilika is unknown as a bird. The name may be compounded of the Sanskrit words mother, and a tree bearing seed like pepper (pothos officinalis), perhaps therefore some spotted bird may have received the epithet…. The next two names are equally unknown, but the former may represent the dandi kak, or raven of Bengal, and the latter in this case may be safely interpreted the common crow, 'the thing of no value,' as the word imports… The next word vedaveyake may be easily Sanskritized as ‘disbelieving the Vedas,’ but such a bird is unknown at the present day…. The ganga puputaka seems to designate a bird which arrived in the valley of the Ganges at the time of the swelling of its waters, or in the rains; as such it may be the 'adjutant,' a bird rarely seen up the country but at that season…. The sankujamava, and the two names following it in the enumeration, are no longer known. The epithet karhatasayake might be applied to the chikor, quasi, sleeping with its head on one side, a habit ascribed in fable to this bird according to the pandit, or it might be rendered the Numidian crane. The panasasesimala may derive its name from feeding on the panasa or jak fruit…. I feel strongly inclined to translate these three in a general way as the perchers, the waders, or web-footed, and those that assort in pairs. The first epithet might also apply to the common fowls in the sense of capon. The mention of the wild and tame pigeon immediately after the above list obliges us to regard all included between the known names at the commencement, and these winding up the list, as birds, or nearly allied to the feathered race; otherwise panasasesimare might easily be broken into a monkey and the gangetic porpoise; and in the same way rekapade might be aptly translated ‘frog;’ sandak, sadaka, or salaka, the porcupine…. The sense requires that a new paragraph should begin with this word although from the final e of the preceding list they might seem all to be classed together in the locative case. As a noun of number, savechatupade may remain singular; in Sanskrit the sentence would run [x]; ye should equally govern a plural verb in the text, where perhaps the anuswara is omitted accidentally in eti and chakhadiyati…. This paragraph as translated in the text would run in Sanskrit with very slight modification [x]. But the expression is awkward from the repetition, (particularly in the original) of the participle kakate with its gerund kataviye. Another very plausible reading occurs to the pandit, making asanmasike vadhi kakate represent the three holy months of the Buddhist as of the brahmanical year, in the months of Aswina, Bhadra, and Karkata (or Kartik), to which these prohibitions would particularly apply; but there are two strong objections to this reading, 1st, that the order of the months is inverted, Kartik, the first in order being found last in the enumeration; and 2nd, the gerund kataviye would be left without specification of the act prohibited. Neither of these is however an insuperable objection, as the act had been just before set forth, and the months may be placed in the order of their sanctity…. This passage varies little from the Sanskrit [x], from the root ‘to hurt, or injure.’ I was led to this root from the impossibility of placing the letter [x] of the inscription in any other place in our alphabet than as [x]. In the Girnar inscription the ordinary r is rendered by [x], which is not to be found in the lats of Delhi, Allahabad, &c., where r is always expressed by l, or a curved form of r, nearly similar in figure. Adding the vowel mark i, we have precisely [x] to express the short sharp ri, in which the burring sound of the r is not convertible so easily into the more liquid sound of l. The aspirated letter ph must necessarily be represented by simple p; at least the corresponding aspirate has not yet been met with on the stone…. The Sanskrit version of this passage hardly differs from the Magadhi, [x]. The termination differs only from the circumstance of the Sanskrit masculine or feminine being replaced by the neuter in the vernacular, as in the Pali language. The contrast, "whether useless, or whether for amusement," does not sound to us so striking as 'whether for use or for amusement,' might have done; but the meaning of the injunction is that even the uselessness of the object shall not be an excuse for depriving it of life…. Jivenajive might admit of three interpretations: 'alive or not alive', jiva najive, i.e., either living or dead, but this is at [x], Sanskrit not to be nurtured. Again [x] is one name for a pheasant, or chakor. But the most obvious and most accordant interpretation is 'that which liveth by life,' to wit a carnivorous animal, which a strict Buddhist could not countenance with consistency…. We now come to the specification of those days wherein peculiar observance of the foregoing rules is enjoined. [X] seems to embrace the whole year, 'in the three four-monthly periods, or seasons;' the expression tisayam punnamasiyam might admit of translation as 'the third full moon,' but a closer agreement with the Sanskrit is adopted in the text by making the [x], which in fact on the stone is separated from the rest, an expletive, quasi 'the evening of the full moon' generally, and this agrees with the Hindu practice; see Sir William Jones' note on the calendar (As. Res. III. 263) where a syamapuja is noted for the 15th or full moon of Aswina (Kartika), a day set apart for bathing and libations to Yama, the judge of departed spirits. It will be remarked that the numbers tinni, chawudasam, pannadasam, are almost as near to the modern Hindi words tin, chauda, pandara, as to the genuine Pali, tini (neuter), chuddasa and pannarasa, three, 14th and 15th. The patipad, Sanskrit [x], is the first day after the full; the Hindus keep particularly the pratipat of the month Kartika (dyuta pratipat) when games of chance are allowed. Dhavaye I have translated 'current', Sanskrit [x], although this word has rather the signification of 'running' in an active sense…. The anuposatham, or rather uposatha, is a religious observance peculiar to the Buddhists; a fast, hardly expresses enough; it requires an abstinence from the five forbidden acts to the laity, or the 8 and 10 obligatory on the upasikas, disciples, and Samaneras, (priests.) 1, destroying life; 2, stealing; 3, fornication; 4, falsehood; 5, intoxication; 6, eating at unpermitted times; 7, dancing, singing and music; 8, exalted seats; 9, the use of flowers and perfumes; 10, the touch of the precious metals. The affix machhe, is equivalent to the Sanskrit [x], or the Pali majjhe, 'midst,' for in our alphabet the jh is always found replaced by chh; had it been separated in the text from anuposatham, it might have been construed with the ensuing words, 'fish unkilled are not to be exposed for sale’ (during the days specified). As it stands, however, avadhya must refer either to 'things unkilled,' or the things whose slaughter is above interdicted must not be sold. The Buddhist scriptures count among the uposatha divasani, or fast days, the panchami, atthami, chatuddasi and pannaras,i or full moon of every month. The first of these is not alluded to in our text, and the pratipat is perhaps included in the 15th day which begins with the evening of the full and reaches into the day after…. The interdiction is here extended to snakes and alligators, the most noxious and destructive reptiles; at least nagavansi, and kevatabhogasi, Sanskrit [x], 'the generation of nagas, and the feeders on fish,' admit of no better explanation…. athamipakhaye, Sanskrit [x], means the eighth day of each paksha or half-month, but perhaps it alludes particularly to the goshthashtami of Kartika, when according to the Bhima parakrama, 'cows are to be fed, caressed and attended in their pastures; and the Hindus are to walk round them with ceremony, keeping them always to the right-hand’… As punavasune, is one of the nakshatras or lunar asterisms, (the 7th,) the preceding word tisaye must be similarly understood as the asterism Pausha. For the reverence paid to this lunar day see the preliminary remarks. Otherwise, it might be rendered trinsye (tithi) on the 30th or full moon, as pannadasa the 15th is employed for the amavasi, or new moon; but against this reading it may be urged that the vowel i should be long (as in the Hindi tisain), and again the enumeration of the days in the luni-solar calendar is never carried beyond the 15th, for as the lunar month contains only 28-1/2 solar days, there would be great trouble in adopting the second period of 15 tithis, or lunar days, to them continuously without an adjustment on the day of change…. Sans. [x], 'cattle shall not be looked at,' or regarded with a view to employment. Were the word simply no-rakhitaviye it would imply that they were not to be 'kept' for labour on such days…. 'On the tishya and punarvasu days of the nakshatric system' must here be understood; as the term 'of every four months,’ and every four half-months would otherwise be unintelligible. The division of the Zodiac into 28 asterisms, each representing one day's travel of the moon in her course, is the most ancient system known, and peculiar to the Hindus. From the motion of the earth it will follow that the moon will be in the same stellar mansions on different days of her proper month at different times of the year, hence the impossibility of fixing their date otherwise than is here done. Although the nakshatras days do not seem now to be particularly observed, yet they are constantly alluded to in the narration of the first acts of the priests. See observations on this head in the preface. We find the word rakhane now introduced, so that it was purposely reserved for application to the beasts of burthen in the climax of the prohibitory law, 'horses and oxen shall not be tied up in the stall on these days!' The termination in e in this and the former instances is curious. It is the 7th case used like the Latin ablative absolute, even with the gerund…. 'Moreover by me having reigned for twenty-seven years, at this present time, five and twenty liberations from imprisonment (are) made.' The verb 'are' or 'shall be' being understood. It is perhaps ambiguous whether 'in this interval' applies to the duration of the 27th year, or to the time previously transpired, yavat signifying both 'until, up to,' and 'as long as, when.'…

Translation of the Inscription on the Eastern compartment….

The omission of the demonstrative pronoun iyam, this, which in the other tablets is united to dhammalipi, requires a different turn to the sentence, such as I have ventured to adopt in the translation: ‘In the 12th year of his reign the raja had published an edict, which he now in the 27th considered in the light of a sin.’ His conversion to Buddhism then must have been effected in the interval, and we may thus venture a correction of 20 years in the date assigned to Piatissa's succession in Mr. Turnour's table, where he is made to come to the throne on the very year set down for the deputation of Mahinda and the priests from Asoka's court to convert the Ceylon court…. I have placed the stop here because the following word, setam, seemed to divide the sentence, 'an edict was promulgated in the 12th year for the good of my subjects, so this having destroyed, or cancelled, I’… Apahata (is) abandoned: viz. the former dhammalipi setam (neuter) is perhaps used for sa-iyam (feminine) so, that; or supplying the word [x] it may run in the neuter [x] and continuing (Pali tam-tam) [x] this (being) as it were a sin according to dharma vardhi (my new religion, so), the expression being connected by tatpurusha samasa…. The text has petavakhati, which may be either read hitavakhati, S. [x], ‘a description for the benefit’, or hetu vakhati, S. [x], ‘description for the sake,' to wit of mankind. Pati vekhami (vakhami), S. [x], ‘I now formally renounce,’ — the affix prati gives the sense of recantation from a former opinion… Sanskrit, [x], ‘among lords, companions, and lieges.’ The last word may also be read, ‘among the sincere or faithful (adherents)’…. Hemeva, for imanva or imaneva, Sanskrit, [x], nikaya, an assembly, may signify the congregations at each of the principal viharas or monasteries…. The construction of this passage is not quite grammatical: echa must he read evamcha; then in Sanskrit [x], 'this (is) for the following after (or obedience) of the soul (myself) as connected with my faith or desire of salvation;' the word upagamane in what is called the nimitta saptami case. I have given what appears the obvious sense. The inscriptions at Allahabad, Mathia and Bakra all end with this sentence, and there is an evident recommencement in the Feroz tablets as if the remainder had been superadded at a later period…. I am by no means confident that the precise sense has been apprehended in the following curious paragraph. The word katham, ‘how’, implies a question asked, to which the answer is accordingly found immediately following, and a second question is proposed with the same preliminary ‘thus spake the raja,’ and solved in like manner, each term rising in logical force so as to produce a climax, that by conversion of the poor the rich would be worked upon, and by their example even kings' sons would be converted, thus shewing the necessity and advantage of continual preaching. For atikata, my pandit reads atikranta, making the whole line; [x]? ataran 3rd. per. pl. 1st. pret. from [x], ‘went to heaven,’ 'as ancient princes went to heaven under these expectations (departed in the faith), how shall religion increase among men through the same hopes?'… The first syllable of this word should perhaps be read no, nochajanne, though differently formed from the usual vowel o; nor will the meaning in such case be obvious. By adopting the pandit's modification, nichajanne, 'vile born,' we have a contrast with the sujanne, ‘well born’ of the next sentence: thus [x]; but though the tha of the word vadhitha belongs only to the second person plural and requires the noun to be placed in the objective case, 'you increase religion,' I incline to read it as a corruption of the future tense vadhisati, or the potential vadheyat…. The letter h in esa mahurtta (an hour, 15th of the day or night) being rather doubtful, I at first took it for a p and translated, 'as my sons and relations'. But it was remarked that only for the anuswara, thrice repeated, the word antikantan would be precisely the same as atikata, above rendered by atikranta. The same meaning would be obtained again by making putha the Sanskrit [x], ‘pure, virtuous’, 'my virtuous ancestors;' but on the whole muhurtha is to be preferred as being nearest to the original…. The verb is here written vadheyati, the ti being perhaps the intensitive or expletive [x] or [x] added to the vadheya of the preceding sentence…. 'what (may not be effected) towards the convincing and converting of the upper classes?' The word anupatipajaya however, from former analogy, will be better rendered by the Sanskrit anupratipadye, which will then require [x] to agree with sujane…. This sentence is unintelligible from the imperfection of two of the letters. The pandit would read [x], but this appears overstrained and without meaning. The last two words ‘dharm shall increase’ point out a meaning, that as (religion and conversion?) go on, virtue itself shall be increased. Adya may perhaps be read Aja…. 'at this time I have ordered sermons to be preached (or to my sons? or virtuous sermons), and I have established religious ordinances.'… 'so that among men there shall be conformity and obedience.' It may be read, 'which the people having heard (shall obey),’ and I have preferred this latter reading because it gives a nominative to the verb…. The anomalous letter of the penultimate word seems to be a compound of gni and anuswara, which would make the reading agnim namisati 'and shall give praise unto Agni,' but no reason can be assigned for employing such a Mithraic name for the deity in a Buddhist document. A facsimile alone from the pillar can solve this difficulty, for we have here no other text to collate with the Feroz lat inscription. It is probably the same word which is illegible in the 19th line. The only other name beginning with a which can well be substituted is Aja, a name of Brahma, Vishnu, or Siva, or in general terms, 'God.' Perhaps Aja, 'illusion personified as Sakti—(Maya),’ may have more of a Buddhistic acceptation….

Inscription round the shaft of Feroz's Pillar. Translation of Inscription round the column….

The only word suitable here is opposition; Ratna Paula would read wisdom. There is no such word as [x] with a cerebral dh. The more proselytism succeeded, the greater opposition it would necessarily meet…. Savapitini should doubtless be savapitani, 'caused to be heard.'… Anusathini (subauditur valhyani), ‘ordinances’, would be the more correct expression, ‘ordered, commanded’…. Yataya papi bahune anasin ayata. The first three letters are inserted in dots on the transcript in the society's possession; it is consequently doubtful how to restore the passage; a nominative plural masculine is required to agree with ayata and govern vadisanti, thus [x]. The meaning of paliye or paliyo is very doubtful: it resembles or contrasts with the viyo of a former part of the inscription. The pandit would have 'on all sides', viz. that they should become missionaries after their own conversion…. Perhaps, 'they shall employ others in speaking' (or preaching)…. The word vadatha being in the second person plural, the rajaka beginning the sentence must be in the vocative, 'oh disciples.' But even this requires a correction from vadatha to vadatha. Ayata and anapita are equivalent to the Sanskrit [x] and [x], ‘having come and being admitted by me,’ — or [x], ‘to them is commanded’, which is best because it leads to the imperative conjunction vadatha…. 'religious establishments are made,' or perhaps pillars, made neuter according to the idiom of the Pali dialect?... the very learned in religion are made, i.e. wise priests appointed. The succeeding word is erased, and it is unnecessary to fill it up, as the sense is complete without. From the last line of the inscription, where thambani occurs, the missing letter may perhaps be read dh, dhara…. Abavadikya of the small or printed text is in the large facsimile ambavabhikya, which leads us to the otherwise hazardous reading of 'mangoe trees;' the word ropapita (applied just before to the planting of trees) confirms this satisfactory substitution…. Several letters are here lost, but it is easy to supply them conjecturally having the two first syllables, nisi and the participle kalapita, ‘and houses to put up for the night in are caused to be built;’ apanani are taverns or places for drinking. Space for one letter follows [x], probably tata tata, Sanskrit [x], ‘here and there’…. literally, 'for the entertainment of beast and man.' The five following letters are missing, which may be supplied by [x], or some similar word…. This neat sentence will run thus in Sanskrit, altering one or two vowels only, [x]. In this the only alteration made are yatha for ya; and rajibhi from rajihi (natural to the Pali dialect,) the third case of raji, ‘a line or descent.’ The application of nama indefinitely is quite idiomatical. The ta may be inserted after hi, but it will read without, 'this people as they take pleasure under my dynasty on account of the various profit and well-being by means of entertainment in my town (or country), (tatha must be here understood) so let them take cognizance of (or partake in) this the fame (or laudable effect) of my religion.' Purihi rajihi may also be understood as in ‘town and country,’ in the translation…. The large facsimile corrects the vowels, te for ta, vidhesu for vidhasu, &c. of the printed transcript; mata is the same in both, but in other places we find mata. The passage may run [x]; the word 'among unbelievers' cannot well be admitted here; 'with kindnesses and favors' may be the word intended, which though feminine in Sanskrit is here used in the neuter. For vayapata, R. P. would read, ‘obtaining age, or growing old’; in the latter case the sense will be that the 'wise unto salvation' growing old in the manifold riches of my condescension and in the favors of the ascetics and the laity growing old — they in the sanghat (sanghatasi for sangha te) or places of assembly made by me — shall attain old age? But mahamata will be much more intelligible if rendered ‘tenets or doctrines’, in lieu of ‘teachers.’ (See preliminary remarks.) Should sanghat be a right reading, it gives us the aspirated g, which is exactly the form that would be deduced from the more modern alphabets; but if an h, the sense will be the same. From the subsequent repetition of the proposition ime vyapata hahanti, with so many nouns of person in the locative case, it seems preferable to take arthesu and pasandesu in the same sense, which may be done by reading the former either as, ‘among the afflicted or frightened, or the rich.’ The verb variously written papanti, hohanti, hahanti, &c. may be [x] rather than [x]; in the yanluk tense, 'shall be occasionally.' [X] here also and further on has the meaning of 'on account of.'… We have here undoubtedly the vernacular word for brahman babhanesu for among brahmans (those without trade), and laity (those following occupations)… The pandit would read, 'do ye enter in or go amongst' (or stedfastly pursue their object), meaning the mahamatas among the people; but this is inconsistent with the te te which require, 'among these several parties respectively, these my several wise men and holy men shall find their way.' The double expression throughout is peculiar, as is the addition after the verb of 'and among all other classes of the Gentiles.' … Here the word [x] is substituted for [x], meaning 'the finished practitioners in religious ceremonial'; for Kamakha read kamaka, or kamatha, [x]; but if mahamata be made 'doctrines', kamaka must be rendered ceremonial…. Devinam S. [x], 'among the whole of my queens', in contradistinction to ni (?) rodhanasi, which may mean 'concubines’… 'with the utmost respect and reverence,' there is evidently a letter wanting after a, which is supplied by a d… The pandit here also enables me to supply a hiatus of several letters: ‘patita (yantu) let them (the priests) thus discreetly or respectfully make their efforts (at conversion)’, — yatanam, exertion pratita, respectful. ...... hida cheva disasu, 'in heart and abroad, within and without;' the application is dubious. I prefer [x] 'with the eyes,' cha dalakanam. The pandit suggests [x] from wife (whence may be formed [x] possessively) of inferior wives, women, but I find 'a son' in Wilson's dictionary, and necessarily prefer a word exactly agreeing with the text…. 'of other queens and princes;' danavisagesu is here put in the plural, which makes it doubtful whether the former should not also be so…. These two words in the 4th case must be connected with the preceding sentence, for the purpose of religious abstraction, apadanam, 'restraining the organs of sense,' has however the second a long. [X] (fem.) is a nazar or present, a calamity; 'for the due ascertainment of dharma,' for a regular religious instruction?... Iyam, feminine, agreeing with pratipatti, the worthier of the two as in Latin…. Of these three coupled qualities the two first are known from the north tablet. The third in the large facsimile reads mandave sadhame, which may be rendered 'among the squalid-clothed, the outcasts (lokasa) of the world.' But though agreeing letter for letter, the sense is unsatisfactory, and I have preferred a translation on the supposition that the derivation of the words is from madhava, sweet, bland, and sadhu, honest. Sadhu is also a term of salutation used to those who have attained arahat-hood…. 'rendering service to father and mother, and the same to spiritual guides;' the next word vaya mahalakanam, is interpreted by R. P. as, 'the very aged'; there is no corresponding Sanskrit word; [x] may be the bald-headed, from forehead. A great man is called barra kapal, from a notion that a man's destiny is written on his forehead; thus, in the Naishadha, when the swan bringing a message from Damoyanti is caught by Nala raja, it laments: "Why, oh Creator! with thy lotus hand, who makest the tender and the cold wife, hast you written on my forehead the burning letter which says, thou shalt be separated from thy mate?"… Duwehi for two-fold, viz.: first 'ia form', the second, niritiya for nrite, dancing according to the pandit; but I would prefer dwihi akarehi (in the Pali 3rd case plural), 'by two signs or tokens;' viz. by voluntary practice of its observances, and secondly 'by freedom from violence, security against persecution.' The Sanskrit would be [x] in the dual…. The half effaced word cannot well be explained; the second is 'let it be reverenced', or 'let reverence be,' probably the word is repeated here as before…. The final sentence I did not quite understand when writing my first notice, having supposed silathabhani to represent the Sanskrit silasthapana. After careful reconsideration with the pandit, we recognize the Pali as rather the exact equivalent for silastambha, a stone pillar (made neuter); the sentence may therefore thus be transcribed [x]. The translation is given in the text, Adhara, a receptacle, a stone intended to contain a record. The words silathabhani and siladhalakani, however, being in the plural and neuter, require kataviyani, also neuter, which may be effected by altering the next word ena to ani; ena being superfluous though admissible as a duplication of esa…. shall proclaim it on all sides (?)… address on all sides (or address comfortably?)… and (resting-places?) for the night… Let the priests deeply versed in the faith (or let my doctrines?) penetrate… I have observed the ordinances myself as the apple of my eye (?)…

**************************

James Prinsep's references to George Turnour in “Interpretation” article:

1. I have said that the founder of the faith is not named. Neither is the ordinary title of the priesthood, bhikhu or bhichhu to be found, though the word is so frequently met with among the Bhilsa danams. The words mahamata, (written sometimes mata) and dhamma mahamata seem used for priests 'the wise men, the very learned in religion.' — The same epithet is found in conjunction with bhikhu in the interesting passage quoted by Mr. Turnour in the preceding article on the Pitakattayan, (see page 506.)

2. But I must now close these desultory remarks, in the hope of hereafter rendering them more worthy of the object by future study and research; and proceed to lay before the Society, first a correct version of the inscription in its own character, and then in Roman letters which I have preferred to Nagari, because the Pali language has been already made familiar to that type by MM. Bournouf and Lassen, as well as by Mr. Turnour's great edition of the Mahavansa, now just issued from the press.

3. 7 / viyo vadisanti 9. [It is best to regard [x] as a compound of dharma and ayatam, length, endurance, — or (from ayat), 'the coming.' The word viyo is unknown to either the Sanskrit or the Pali scholar, they suppose it to be a term of applause attached to [x] 'they shall say,' as in the modern Hindvi tumko bhala kahengi, they shall say 'well' to you, they shall applaud you. [x] to praise, may be the root of the expression. It also something resembles the Io of the Greeks, which however like eheu is used as an expression of lamentation; and this meaning accords also with the word viyo in Clough's Singhalese Dictionary. — Viyo, viyov, viyoga, 'lamentation, separation, absence.' Viyo-dhamma is translated 'perishable things' by Mr. Turnour, in a passage from the Pitakattayan. See p. 523.]

4. 2 / vasa abhisitename, dhammalipi likhapita 1 [The omission of the demonstrative pronoun iyam, this, which in the other tablets is united to dhammalipi, requires a different turn to the sentence, such as I have ventured to adopt in the translation: In the 12th year of his reign the raja had published an edict, which he now in the 27th considered in the light of a sin. His conversion to Buddhism then must have been effected in the interval, and we may thus venture a correction of 20 years in the date assigned to Piatissa's succession in Mr. Turnour's table, where he is made to come to the throne on the very year set down for the deputation of Mahinda and the priests from Asoka's court to convert the Ceylon court.]

by James Prinsep, Sec. As. Soc. &c.

1837

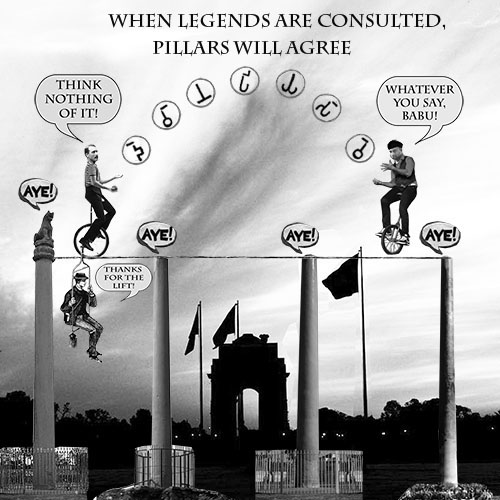

[George Turnour] Thanks for the lift!

[James Prinsep] Think nothing of it!

[Pandit Kamalakanta] Whatever you say, Babu!

[Lauriya Nandangarh Pillar] Aye!

[Feroz Shah Pillar] Aye!

[Lauriya Areraj Pillar] Aye!

[Allahabad Pillar] Aye!

"When legends are consulted, Pillars Will Agree", by Tara and Charles Carreon

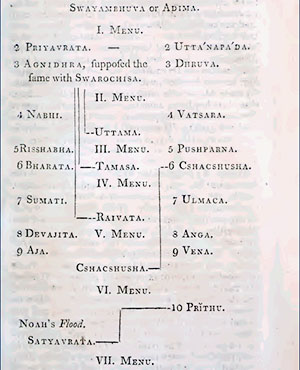

James Prinsep is a legend, a man whose linguistic achievements were unprecedented, because he assayed to do what no one had ever done before -- ignore all the impediments to decoding the numerous stone carvings of unknown scripts that had frustrated others. Those impediments were that no one knew who had written which carvings, when they had written them, in what alphabet they had written, and what language they had used (since ancient Indian scripts encode a variety of languages using a single phonetic system). His efforts were unusually strenuous, if entirely wrong-headed in a number of ways, and continued for years, until they were crowned with a "success" he would not allow to elude him. Today, his "interpretations," which he later claimed were "translations," are celebrated as miraculous, precisely because no one can repeat them. As the picture above illustrates, Prinsep carried the fantasies of George Turnour's Dipavamsa from the pages of Ceylonese dynastic fiction across a tightrope of daring assumptions, claiming to draw from the tumbled stones of India, proof that it had once been ruled by Ashoka, whose name until then had been among the most minor kings of India’s Puranic dynastic history. The evidence of Prinsep’s own writing shows how he and Turnour determined the meanings to be applied to pillar inscriptions, and that Turnour was the dominant partner in the interpretive project, being more than willing to impute Buddhist hagiographic language to the epigraphs. Although Turnour’s “identification” of Devanampriya Priyadarsi as Ashoka took Prinsep by surprise, because Turnour had previously published the Mahavamsa, that identified Devanampriya Priyadarsi as a Ceylonese ruler, Prinsep quickly adapted, and ceded the point to Turnour in the pages of his own Asiatic Journal.

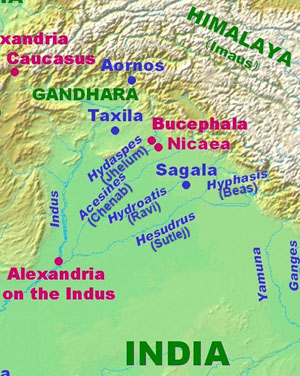

With the assistance of compliant Brahminical "scholars" who knew no better than Prinsep himself the language they were claiming to decipher, and the bizarre imputation of Indian historical significance to the Ceylonese Dipavamsa (and ignoring Turnour’s contrary statements in the Mahavamsa that both Turnour and Prinsep had previously embraced), the pair hijacked Indian history for Ashoka and his imaginary father, "Chandragupta Maurya." So that these imaginary rulers would not be without material achievements, they transferred to them the achievements of Alexander's Diadochi, who ruled the mountain kingdoms of Swat and Gandhara that now are occupied by Northwestern India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. Being the works of the Diadochi, who integrated both Persian and Greek linguistic abilities within their domain, the alleged "Ashokan" rock pillars and edicts are scribed in Kharosthi (an Aramaic-derivative that reads right to left), or an unknown script that has been dubbed "Brahmi" (a script that reads left to right, and has a likely Greek origin). Unaware of the nature of these scripts, Prinsep (who had no personal linguistic ability) directed his men to compare them all with Sanskrit and Pali (assuming a Buddhist origin). Further, even if the script, be it Brahmi or Kharoshthi, was decoded by Prinsep, these were only alphabets, and he had no dictionary, nor did he know which language these scripts had been used to encode. He did not know where words ended and began. And he claimed the amazing ability to know just when it was okay to change one symbol to another, changing word lengths, spellings and meanings just as needed to solve his Buddhist crossword puzzle.

Prinsep, in his energetic, creative ignorance, crammed all epigraphic evidence into the Procrustean mold of the Dipavamsa's Ashokan fantasy, extracting the image of a "Buddhist ruler" from numerous fragments that he conveniently combined into a single message which he later claimed, without evidence, appears in the same form on all pillars -- an insupportable conjecture that the entire world of Indic studies appears to have swallowed whole. Prinsep further ignored the already-established fact that all of the coins in this region were minted by the Diadochi, and all of the archaeological finds in this area conclusively establish a continuity of Persian rule followed by Greek rule, followed by Sakan rule, followed by Kushan rule, leaving no room for mythical Mauryan rule during the disputed period of 350 BC through 185 BC.

Whatever might be said of Prinsep, he was not shy about his claimed achievements. The method he used to "interpret" the pillar inscriptions was a one-off achievement that he declared successful only because he met his own preconceived goals of proving that Ashoka was responsible for the carvings on various of the pillars. He did not develop a methodology that anyone has applied to decipher epigraphs elsewhere. Because his conclusions were so convenient to the political demands of the moment, when the British East India Company was eagerly defining the future of India by defining its past, they have never been scrutinized. And thus the absurd hubris inherent in the title above-quoted, that the pillar inscriptions themselves "agree" with his conclusions, has never been remarked upon. Until now.

"Interpretation" Highlights:

The difficulties with which I have had to contend… the orthography is sadly vitiated [the spelling is spoiled]… the language differs essentially from every existing written idiom… a degree of license is therefore requisite in selecting the Sanskrit equivalent of each word, upon which to base the interpretation — a license dangerous in the use unless restrained within wholesome rules; for a skilful pandit will easily find a word to answer any purpose if allowed to insert a letter or alter a vowel ad libitum…. some substitutions authorized by analogy to the Pali… have for their adoption the only excuse, that nothing better offers…

[F]rom the incompleteness of the lines on the right hand the context cannot thoroughly be explained… We might translate the whole of the first line [x] … and other insulated words can be recognized but without coherence…. The general object of Devanampiya's series of edicts is, according to my reading, to proclaim his renunciation of his former faith, and his adoption of the Buddhist persuasion… He addresses to his disciples, or devotees, (for so I have been obliged to translate rajaka, as the Sanskrit [x], though I would have preferred rajaka, ministers, had the first a been long … the chief drift of the writing seems directed to enhance the merits of the author…

It is a curious fact that… the name of the author of that religion is nowhere distinctly or directly introduced as Buddha, Gotama, Shakya muni, &c…. the expression Sukatam kachhati, which I have supposed to be intended for sugatam gachhati, may be thought to contain one of Buddha's names as Sugato… but the error in spelling makes the reading doubtful… In another place I have rendered a final expression …'shall give praise to Agni' — a deity we are hardly at liberty to pronounce connected with the Buddhist worship…

It is only by the general tenor of the dogmas inculcated, that we can pronounce it to relate to the Buddhist religion…. The sacred name constantly employed…. is Dhamma (or dharma), 'virtue;'… Buddhism was at that time only sectarianism; a dissent from a vast proportion of the existing sophistry and metaphysics of the Brahmanical schools, without an absolute relinquishment of belief in their gods, or of conformity in their usages, and with adherence still to the milder qualities of the religion… The very term Devanampiya, 'beloved of the gods,' shews the retention of the Hindu pantheon generally… The word [dhamma] is here evidently used in its simple sense of "the law, virtue, or religion"… though … there is no worship offered to it, no godhead claimed for it….

The word dhamma is in the document before us generally coupled with another word, vadhi… The most obvious interpretation of the word vadhi is found in the Sanskrit vriddhi, increase… 'the increase of virtue,' 'the expansion of the law,' in allusion to the rapid proselytism which it sought and obtained…. Against this interpretation, if it be urged that the dental dh is in other cases used for the Sanskrit dh, as in the word dharmma itself; in vadha, murder; bandha, bound, &c., such objection may be met by [x]… It is hardly possible to imagine that two expressions so strikingly similar in orthography as dhammavadhi and dhammavatti or vadai, yet of such opposite meaning, should be applied to the same thing. One must be wrong, and I should have had no question which to prefer…

I requested my pandit Kamalakanta to look into … this expression 'wheel of the law'… the actual employment of the term dharma vriddhi was wanting… the pandit met with many instances of the word vriddhi occurring in connection with bodhi, which as applied to the Buddhist faith was nearly synonymous with dharma… the growth of knowledge, or metaphorically the growth of the bodhi or sacred fig tree…. Daya is written taya: idavala, ajavala, and samaguni, samagini: in fact the whole volume is so full of errors of transcription that it was with difficulty Kamalakanta could manage to restore the correct reading…. This passage is corrupt and consequently obscure, but it teaches plainly that dharmavriddhi of our inscription may always be understood, like bodhivridhi, in the general acceptation of 'the Buddhist religion.' Proselytism, turning the wheel, or publishing the doctrines, whichever is preferred, was evidently a main object of the Buddhist system, and it is pointed at continually in the pillar inscription….

[ B]rahmans, the arch-opponents of the faith, are also named, under the disguise of the corrupt spelling babhana… I have said that the founder of the faith is not named. Neither is the ordinary title of the priesthood, bhikhu or bhichhu, to be found…

The words mahamata, (written sometimes mata) and dhamma mahamata, seem used for priests, 'the wise men, the very learned in religion.'… The same epithet is found in conjunction with bhikhu in the interesting passage quoted by Mr. Turnour… But it is possible that this expression has been misunderstood by the pandit… Mr. Hodgson's epitome, above alluded to, gives us another mode of interpretation perhaps more consonant with the spirit of the system… the great mother of Buddha — the universal mother, omniscience, illusion, maya, &c. — and as such may be more correctly supposed to pervade than mahamata the priests…

[T]here is no allusion to the vihara by name, nor to the chaitya, or temple: no hint of images of Buddha's person, nor of relics preserved in costly monuments. The spreading fig tree and the great dhatris, perhaps in memory of those under which his doctrines were delivered, are the only objects to be held sacred…

The edict prohibiting the killing of particular animals is perhaps one of the most curious of the whole…. Many of the names in the list are now unknown, and are perhaps irrecoverable, being the vernacular rather than the classical appellations…. I have pointed out such endeavours as have been made by the pandits to identify them… Others of the names in the enumeration of birds not to be eaten will remind the reader of the injunctions of Moses to the Jews on the same subject. The list in the 11th chapter of Leviticus comprises 'the eagle, the ossifrage, the ospray, the vulture and kite: every raven after his kind, the owl, night hawk, cuckoo and hawk; the little owl, cormorant and great owl: the swan, pelican, and gier-eagle; the stork, heron, lapwing and bat… The verse immediately following the catalogue of birds, "All fowls that creep upon all four shall be an abomination unto you," presents a curious coincidence with the expression of our tablet… which comes after … the tame dove….

But the edict by no means seems to interdict the use of animal food… It restricts the prohibition to particular days of fast… The sheep, goat, and pig seem to have been the staple of animal food at the period… but merit is ascribed to the abstaining from animal food altogether…. Ratna Paula tells me no similar rules are to be found in the Pali works of Ceylon, nor are the particular days set apart for fasting or upavasun in the inscription, exactly in accordance with modern Buddhistic practice… All the days inserted are, however, of great weight in the Hindu calendar of festivals… the two lunar days mentioned in the south tablet, tishya (or pushya) and punarvasu, though now disregarded, are known from the Lalitu Vistara to have been strictly attended to by the early priests… proving that the luni-solar system of the brahmans was the same as we see it now, three centuries before our era, and not the modern invention Bentley and some others have pretended….

(If I have read the passage aright) opposition was contemplated as conversion should proceed… royal benevolence was exercised in a way to conciliate the Nanapasandas, the Gentiles of every persuasion, by the planting of trees along the roadsides, by the digging of wells, by the establishment of bazars and serais, at convenient distances. Where are they all? On what road are we now to search for these venerable relics… [that] would enable us to confirm the assumed date of our monuments? The lat of Feroz is the only one which alludes to this circumstance, and we know not whence that was taken to be set up in its present situation by the emperor Feroz in the 14th century… This cannot be determined without a careful re-examination of the ruinous building surrounding the pillar… The chambers described by Captain Hoare as a menagerie and aviary may have been so adapted from their original purpose as cells for the monastic priesthood… The difficulties and probably cost of its transport, which, judging from the inability of the present Government to afford the expense even of setting the Allahabad pillar upright on its pedestal, must have fallen heavily on the coffers of the Ceylon monarch!...

The Allahabad version is cut off after the 3 first letters of the 19th line… The Mathia and Radhia lats contain it entire, adding only iti at the conclusion, and after Sache Sochaye in the 12th line…. The second part of the Allahabad inscription begins to be legible at the 12th letter of the 14th line. The whole is to be found on the Radhia pillar… The termination at Mathia differs in having inserted after the 3rd letter of the 20th line the words [x]… The word Ajakanani at the end of the 7th line seems accidently to have been omitted in the Feroz lat. It is supplied from the Radhia and Mathia pillars. The Allahabad version is erased from the 3rd letter of the 6th line…. The Mathia and Radhia inscriptions terminate with the tenth line. The remainder of this inscription and the following running round the Column are peculiar to the Delhi monument….

Translation of the Inscription of the North compartment….

The whole of the northern tablet, although composed of words individually easy of translation, presents more difficulties in a way of a satisfactory interpretation than any of the others. This first sentence particularly was unintelligible to Ratna Paula, who for Dusampati would have substituted Dasabala, 'the tea (elephant) powered,' a name of Buddha. The pandit's reading seems more to the purpose… The sense of this passage, although at first sight obvious enough, recedes as the construction is grammatically examined. I originally supposed that Annata was meant for Ananta, the anuswara being placed by accident on the left, and had adopted the nearest literal approach to the text in Sanskrit for the translation… but in this it was necessary to omit two long vowels, in parikhaya and sususaya to place them in the third case. By making them of the fifth case, (in Sanskrit the nyabalope panchami), and by reading Anyata, every letter can be exactly preserved with the sense given in the present translation… the most doubtful words are usritena and chaksho; the latter Ratna Paula would break into cha-kho, 'and certainly' (kho for khalu); the former may be replaced by 'by perseverance,' but this is hardly an improvement. It is also a question whether Dhamma kama is to be applied in a good sense as 'intense desire of virtue,' or in a bad, as 'dominion of the sensual passions.'… This sentence is equally simple in appearance, though ambiguous in meaning from the same cause; kamata is however here applied in the good sense with dharma…. Either 'having obtained devout meditation,' or, which is nearer the text [x], from 'abstinence from passion,' the participle termination twa from the prefixing of pra, becomes yap, or is changed to [x]… mahamata, supremely wise, may be made nearer to the text, where the third a is long, by reading mahamatra, being the holiest act of brahmanical reverence, accompanied by the closing of every corporeal orifice… This passage is somewhat obscure, but it is tolerably made out by attention to the cases of the pronouns and the four times repeated Dharma in the third case… but the aspirated d and the separation of ya would favor the reading, 'this is the true path, or rule,' &c. In either case there are errors in the genders of the pronouns…. Apasinavai… alluding either to the words [x], or the non-omission of deeds just mentioned, or to what follows…. But I prefer the more simple acts, in the neuter like the preceding kiyam: the Sanskrit kriya is however feminine…. [x] may also be read, of the same signification, purity from passion or vice. Chakhuradan is explained in Wilson's Dictionary as 'the ceremony of anointing the eyes of the image at the time of consecration', but it is also allegorically used for any instruction, or opening of the eyes derived from a spiritual teacher…. A very easy sentence; the construction is as that of the Latin ablative absolute, 'many kindnesses being done of me, towards the poor,' &c…. This is also equally clear: aprana may here allude to vegetable life, or to that which doth not draw breath; benevolence to inanimate things. For [x] also grain, food, may be intended. A better sense for apana may be obtained by reading pleasing and conciliatory demeanour…. If ye and se are here preferred, the verbs must be plural, otherwise ya and sa are required. In this, the only method of reading the text, there is a corrupt substitution of k for g twice: but other instances of the same substitution occur elsewhere…. In the translation I have supposed iyam to be ayam, in the neuter, and have taken dekhati, as allied to the vernacular dekhna, which in Sanskrit changes in this tense to drishyate or, is seen…. this is called Asinava, a word of unknown meaning. The pandits would read adinava, transgressions, but the word is repeated more than once with the same spelling, and must therefore be retained…. An obscure passage, chakho (written chukho) being neuter does not agree with esa m., overruling this as an error, we may make dekhiya, is precisely the modern Hindi subjunctive, 'may or shall it see.'… The ti does not exist on the Feroz lat though it is retained on the others. Asinava gamini is the former unknown term, which seems here to mean the nine asa or petty offences…. Some of these agree with the nine kinds of subordinate crimes enumerated in Sanscrit works, which are as follows: ignorance, deceit, envy, inebriety, lust, hypocrisy, hate, covetousness, and avarice….

Translation of the West inscription….

Had the a been long the preferable reading would have been rajaka, assemblies of princes or rulers, quasi courtiers or rulers…. [x] is the pandit’s reading, making rajaka in the vocative, 'oh devotees who are come in many souls, in hundreds of thousands of people', but in this reading janasi, which is found alike in all the texts, must be placed in the 7th case plural, … (Pali janasi ayata), 'having come into this knowledge', is, I think, preferable, and is accordingly adopted…. If the i be long, the word would signify, 'without fear, fearless.'… 'circumambulations must be practised', or 'pious acts,' will be closer to the original. To the termination evu the other lats add ti in this and the following instances. The former agrees with the vernacular hove, 'let be,' the latter with the Sanskrit 'is to be.'… 'shall they become prosperous or unfortunate,' according to the pandit; but a nearer approach to the construction of the text may be formed, 'shall know good or bad fortune.'… It is best to regard [x] as a compound of dharma and ayatam, length, endurance, — or (from ayat), 'the coming.' The word viyo is unknown to either the Sanskrit or the Pali scholar, they suppose it to be a term of applause attached to 'they shall say,' as in the modern Hindvi tumko bhala kahengi, they shall say 'well' to you, they shall applaud you. To praise, may be the root of the expression. It also something resembles the Io of the Greeks, which however like eheu, is used as an expression of lamentation, and this meaning accords also with the word viyo in Clough's Singhalese Dictionary. — Viyo, viyov, viyoga, 'lamentation, separation, absence.' Viyo-dhamma is translated 'perishable things' by Mr. Turnour in a passage from the Pitakattayan… perhaps the 'some little' given of the inhabitants of the village, and preserved shall be on account of worship,' (or they shall give trifling presents to make puja?)… This passage is rather obscure in its application to the preceding; the pandit reads 'the devotees also speak,' but the letter p is uncertain, and I would prefer, ‘shall receive, and having proceeded my devotees shall obtain the sacred offering of chandan’; [x] being read by the pandit as sandal-wood, an unctuous preparation of which is applied to the forehead in pujas, but the aspirated ch makes this interpretation dubious: chhandani are solitary private (occupations) or desires…. An unknown letter in the word chayanti or chapanti leaves this sentence in the same uncertainty. Adopting the former we have, 'by which my devotees (may) accumulate for the purpose of the worship, to pay the expenses of the worship from the accumulated nazars and offerings.'… A new subject here commences, 'moreover let my people frequent the great myrobalan trees (which also the Hindus prize very highly and desire to die under) in the night.' Thus reads the pandit, but the last word is [x], not yatu; and it may be an adverb implying, 'occasionally', or prohibiting altogether. Viyataye may also mean 'for the learned,' viyata in Pali being a scholar, in which case I should understand [x] as the name of some third tree (like the nyctanthes tristis or the white water-lily which opens its petals (or smiles at night) so as to connect the dhatri with the asvattha, or holy fig-tree, thus, 'the dhatri, nisijati and asvatha shall be for the learned.'… The same expression here recurs: 'my people accumulates (or plants?) the auspicious, or the great myrobalan'; perhaps 'caresses' is to be preferred in both places…. A new enjoinder, [x] or, following the Bakra and Mathia texts, may mean, 'the pleasure of drink (vinous liquor) is to be eschewed,’ but for this sense the words should be inverted, as [x]. The exact translation as it stands is, 'pleasure, as wine must be abandoned,' a common native turn of expression, — 'do this (as soon) take poison.'… A curiously introduced parenthesis, 'much to be desired is such glory!’... something is wanting to make the next word intelligible, avaite, &c., as if 'but they shall not be put to death by me.'… 'of men deserving of imprisonment or execution, pilgrimage (is) the punishment (awarded)?' This, the only interpretation consonant with the scrupulous care of life among the Buddhists, is supported by the genitive case of munisanam, yet a closer adherence to the letter of the text may be found in 'the adjudged punishment.' If by [x] pilgrimage be intended, 'banishment,' there is no such disproportion being the punishment awarded as might be at first supposed. It is in the eyes of natives the heaviest infliction…. The general meaning of this sentence can easily be gathered, but its construction is in some parts doubtful, the words [x] follow the same idiom as above, the three days of (or for) the highway robbers or murderers; my, generally placed before the verb or participle (as me kate passim) inclines me to read yote as [x] or [x], though usually written vute … Dine natikavakani is transcribed by the pandit 'among the poor people, blasphemies, or atheistical words,' but this does not connect with the next word ni ripayihanti, where we recognize the 3rd plural of the future tense of root to hurt or injure with the prohibitive ‘not’ prefixed. Perhaps it should be understood 'neither among the poor or the rich shall any whatever (criminals) be tortured (or maimed).' … Here are two other propositions coupled together; tanam I think should be beating, and destroying; jivitayetaram might thus be cruelty to living things. But I adopt this correction only because I see not how otherwise sense can be made…. [x] must be the vernacular corruption of 'they shall pay a fine, or give an alms.'… A doubtful passage for which I venture thus: 'It is my desire thus that the cherishing of these workers of opposition shall be for the (benefit) of the worship,' meaning that the fines shall be brought to credit in the vihara treasury?... The wind-up is almost pure Sanskrit …

Translation of the Inscription on the Southern compartment….