by Frank Frost Abbott

Classical Philology III

January, 1908

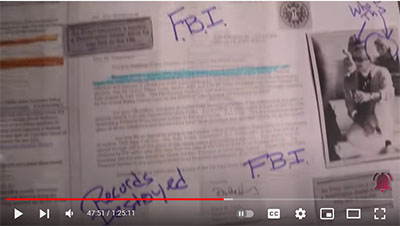

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

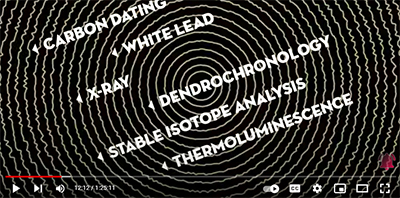

Several scholars in modern times have written chapters on literary forgery, but no one seems to have studied in a comprehensive way epigraphical forgery and the methods which are employed in detecting it, although there is no field of classical study in which dishonesty has brought such confusion, as in epigraphy, and, on the other hand, in no investigations have scholars displayed more acuteness than they have shown in detecting spurious inscriptions. This paper, however, does not aim to give a complete survey of the subject. Its purpose is merely to bring together a sufficient body of facts from the notes in the Corpus and from the reports of scholars in the epigraphical journals to show the development of the art, and to illustrate the methods of some of its most famous, or infamous, promoters.

It was so easy two or three centuries ago to compose an important inscription, and to win distinction by publishing it to the world, and so difficult to detect its spurious character, that many scholars yielded to the temptation. Furthermore, the opportune publication of a forged inscription might save a weary search in establishing a point, furnish a missing link in a chain of evidence, or administer a coup de grace to a stubborn opponent. In view of this situation we are not surprised to find that the number of spurious or suspected inscriptions mounts up to 10,576 in a total of 144,044, corresponding to a ratio of about one spurious to thirteen authentic inscriptions. The condition of things in the several volumes of the Corpus varies greatly. Against Vol. VII, with only 24 spurious and 1,355 authentic inscriptions, stand [size=1 10]Vols. IX and X, which cover the old kingdom of Naples, with totals for the two volumes of 1,854*1 and 14,841, which stand to each other in the ratio of one to eight. [/size]These differences between the several volumes in the matter of forged inscriptions, of which the cases just cited are characteristic, tempt one to an estimate of the comparative honesty of the Spanish, Roman, Neapolitan, French, or English epigraphist and antiquarian. Two or three independent facts also seem to indicate that the national standards in this matter among the several European peoples have not been the same. Thus, for instance, Donius in the seventeenth century, fresh from the chagrin which his deceitful amanuensis Grata had caused him, writes to a friend expressing a desire for a Belgian to fill the position of secretary for him "cum Itali plerique huic officio parum idonei sint" [Google translate: whereas most Italians are unfit for this duty] (cf. CIL, VI. 5, p. 228*). and Borghesi was so indignant at the large number of forgeries from Naples that he was inclined to hold all Neapolitan inscriptions under suspicion. On the other hand, the Englishman may feel some national pride in the fact that only 24 spurious inscriptions are found in the collection from Britain. But conclusions based on national or geographical considerations must be drawn with great care, for, in point of fact, all the principal continental peoples of Europe -- the Italians, the Germans, the French, and the Spanish -- have had representatives in the art of forgery, and an examination of the spurious inscriptions shows that the composition of them is characteristic of a particular period rather than of a given region. The publication of fictitious inscriptions goes back to the fifteenth century and was practiced as late as the middle of the last century, but its Augustan age runs from the middle of the sixteenth to the middle of the seventeenth century. Since Italy furnished the most fruitful field for epigraphical study at that time, as it does today, and since, consequently, Italians out-numbered others in cultivating it, it is not strange that Italian forgeries are more numerous than those from other sources. It is also true, as we shall have occasion to notice, that two or three Italian scholars were very prolific in this field and, therefore, have brought up the national average. Turning from the geographical factor to the time-element, perhaps we should not boast too much, at the expense of our predecessors, of the higher standard of epigraphical morals which prevails now, because the certainty of detection exerts a most salutary deterrent influence upon those who might be inclined to sin in this matter today. We have now a systematic collection of inscriptions; critical principles are well established, and interest in classical antiquities is so general and all parts of the Roman world are reached today with such comparative ease, that a forgery, or the attribution of a forged inscription to a particular place, would be readily detected.

Felix Felicianus of Verona, of the fifteenth century, who is perhaps best known for an interesting little treatise upon the letters of the alphabet and the best methods of drawing them (cf. R. Schone in Eph. Epigr. I, p. 255 if.), may perhaps be regarded as the father of epigraphical forgery. The art did not appear in its completed form at once, and the earliest practice of it was comparatively naive and harmless. Felicianus and his immediate successors never, or rarely, forged inscriptions outright, but they pretended to find in some ruin an inscription mentioned by an ancient author, or their fictitious finds were based upon some statement found in literature. Thus Michael Ferrarinus reports as one of his discoveries the epitaph of Ennius, obviously taking the text from Cic. Tusc. i. 34:, and Mazochius in his Epigrammata antiqua urbis, published in 1521, reports the following inscription: Divo Gordiano victori Persarum, victori Gothorum, victori Sarmatarum, depulsori Romanorum seditionum, victori Germanorum, sed non victori Philipporum [Google translate: To the god Gordianus the conqueror of the Persians, the conqueror of the Goths, the conqueror of the Sarmatians, the repulsor of the Roman rebellions, the conqueror of the Germans, but not the conqueror of the Philippi](CIL. VI. 5.1* S). This is of course taken bodily from the life of the three Gordians (chap. 34:) by Julius Capitolinus. The latest known forgeries are those of Chabassiere, a French engineer who in 1866 published through the Academy of Constantine several African inscriptions, one of which, an inscription of king Hiempsal, was recognized as a forgery by both Mommsen and Wilmanns (cf. CIL. VIII, p. 489), and cast discredit upon all the other inscriptions reported by Chabassiere alone.

If the Berlin Academy had persisted in following up the plan, which it had adopted in 1850 at Zumpt's suggestion, of basing the Corpus mainly upon the epigraphical texts given in manuscript and printed collections, probably most of the spurious inscriptions which have been composed during the four centuries which intervene between Felicianus and Chabassiere, and which now languish under the dreaded star, would never have been thus stigmatized. Fortunately, Mommsen, before publishing an inscription, insisted upon examining the stone, whenever it was in existence, and demonstrated the feasibility of his plan and the correctness of his method in his Inscriptiones regni Neapolitani [Google translate: Inscriptions of the kingdom of Naples], which appeared in 1852. Fortunately, too, Mommsen had, perhaps unwittingly, selected for this first scientific collection a field, viz. the kingdom of Naples, where forgers, as we noticed above, had been most active. The attention of the editors of the Corpus was thus drawn at the outset to the importance of detecting forged and interpolated inscriptions, and many of the critical principles upon which the science rests today were formulated and applied by Mommsen in this preliminary work (cf., e. g., CIL. IX, p. xi). From this early period comes, for instance, the well-known classification of all previous collectors in three categories: (1) the honest and careful, (2) the dishonest, and (3) the negligent, credulous, or ignorant. The principle of classification adopted for the second group is Calvinistic in its severity. One demonstrated lapse from honesty on the part of a collector condemns every inscription for which the scholar in question is our only direct source of information. The sweeping character of this critical rule is probably responsible for putting many authentic inscriptions in the suspected list, and some cases of this sort have already come to light (cf. CIL. VI. 5, pp. 253*-55*). It would seem desirable soon to examine these lists in the several volumes systematically in the light of new discoveries and of our increased knowledge, in the hope of rescuing authentic inscriptions from their present position among the suspected or condemned. That the principle underlying the second grouping of collectors does not lean toward lenity seems to be indicated also by the fact that no inscription regarded by the editors of the Corpus as authentic has been condemned later.

The most prolific forgers in the period from Felicianus to Chabassiere were Boissard, Gutenstein, Ligorio, Lupoli, Roselli, and Trigueros. The names -- French, German, Italian, and Spanish -- indicate, as observed above, that scholars of all the principal continental countries were guilty of this offense. The devious methods of Francisco Roselli are especially hard to follow because he at the same time forged some inscriptions and copied many other authentic ones, but copied them carelessly. His collection, which was made up partly of inscriptions from Grumentum, was published in 1790, and Mommsen, finding it very difficult to make a correct estimate of his work from the published collection, went to Grumentum in 1S46 to study his method of procedure. He found that the people of Grumentum regarded Roselli as their most distinguished citizen, and they gave their visitor all the help they could to make the fame of their fellow-townsman known as widely as possible. Mommsen's embarrassment when he discovered the true character of Roselli and had to publish the facts is best indicated in his own words (CIL. X, p. 28): "Grumenti autem qui studia mea adiuverunt viri optimi, quorum memoriam grato et pio animo recolo, nolint mihi irasci, quod libere de Rosellio locutus sum et verus magis esse volui quam gratiosus." [Google translate: But the Grumenti, who have aided my studies, the good men, whose memory I remember with a grateful and pious heart, do not want to be angry with me, because I spoke freely about Roselli and wanted to be true rather than popular.] Among other peculiarities Roselli's MS shows some very interesting afterthoughts. In one case (CIL. X. 43*) he forged an inscription in honor of a certain Q. Attius in which the people of his native town were characterized as Bruttii, but, finding later that they were really of Lucanian origin, he revised his inscription by dropping out the line in which the Bruttian origin was mentioned.

Roselli's purpose was apparently to bring distinction to himself and his native town. Gutenstein's motive was more altruistic. He was Gruter's amanuensis and not only reported authentic inscriptions to his master but also forged others to gratify Gruter's intense desire for additions to his collection. Many of his inscriptions he pretended to have found in the collections of Metellus and Smetius. His dishonesty was discovered when these collections were examined and Gutenstein's inscriptions were not found among them (cf. CIL. VI. 5.3226*-3239*; Bormann Eph. Epigr. III, p. 72). His epigraphical style is well illustrated by Mommsen in Eph. Epigr, I, pp. 67-75. One of the inscriptions there quoted is in honor of Septimius Severus. Another reads as follows: DDD. nnn. | Valentiniano Valenti et | Gratiano Auggg | piis felicibus ac | semper triumfator. | signum Herculi vict. | ob prov .... | rect .... | ampli .... | votis X | .... is xx. [Google translate: DDD nnn | Valentinian Valenti and | Gratiano Auggg | to the pious and happy always triumphant | sign of Hercules defeated | for prov... | right .... | wide .... | wish X | .... it is xx.] On these two Mommsen remarks (p. 68): "primae honores honorumque iterationes tam facile explanabis quam Geryoni aptabis petasum; in secunda imperatores tres intemeratae Christianitatis signumque Herculis victoris simul splendent tamquam in eodem caelo Sol et Luna." [Google translate: You will explain the first honors and the repetitions of honors as easily as you fit Geryon's hat; in the second, the three emperors of undefiled Christianity and the symbol of Hercules the victor shine together as if the Sun and the Moon were in the same sky.]

The method of Lupoli, a bishop at Venusia, was to take inscriptions from the collections of Gruter and Fabretti, add a few genuine ones of his own, and forge others to complete his collection. His work is characterized by the stern indignation which he expresses at the inaccuracy and dishonesty of other epigraphists.

In the Rh. Mus. XVII (1862), pp. 228 ff., Hubner tells in a graphic way how he unmasked Trigueros. The conduct of the Spanish epigraphist was peculiarly and ingeniously perfidious, because he attributed his own forged inscriptions to a scholar of a previous generation who was' probably a creation of his own imagination. He had already taken a similar course in the case of a piece of literature forged by him, so that this method of procedure must have appealed to his malicious sense of humor.

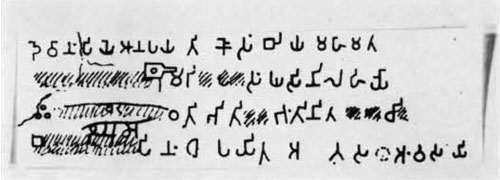

But the prince of forgers was the Neapolitan Pirro Ligorio of the sixteenth century. In a burst of indignant admiration de Rossi characterizes him (Inscr. Chr. urbis Romae, p. xvii * [Google translate: Inscr. Chr. of the city of Rome, p. xvii *]) as "magnus ille fallaciarum opifex et parens." [Google translate: He is a great maker and parent of deceptions.] Ligorio held a very distinguished position among the scholars and artists of his day, was the friend of Smetius, Pighius, and Panvinius, and succeeded Michelangelo in supervising the work at St. Peter's. The Vatican library has twelve manuscript volumes from his hand, the Barberini ten, and the library at Turin, at least up to the time of the late injury to that collection by fire, thirty more. Of the 3,643 spurious inscriptions which CIL. VI, pt. 5, contains, 2,995 emanate from Ligorio. His audacity is incredible. Many of his forgeries he pretended to have found in the gardens or libraries of well-known houses in Rome (cf. CIL. VI, pt. 1, p. lii, col. 1), and as a rule he mentions the exact location, e. g., he locates VI. 1460* "dentro la chiesa di San Nicola di Cavalieri in via Florida presso della Calcare." [Google translate: inside the church of San Nicola di Cavalieri in via Florida at della Calcare.] Sometimes he gives an airy description of the supposed monument, as in VI. 1463*, "in essa si vede la imagine della Gorgona et pare che gli volano a destra et a sinistra due farfalle. Con un festone di frutti." [Google translate: in it we see the image of the Gorgona and it seems that two butterflies fly to the right and to the left. With a festoon of fruit.] Sometimes he based his productions on a single authentic inscription (cf. VI. 1819* and VI. 1409); sometimes he combined two authentic inscriptions (cf. VI. 1866* and VI. 1739, 1764)" but more frequently he forged outright. His versatility in the matter of content and form is extraordinary. He treats a great variety of subjects, combines Greek and Latin (e. g., VI. 1653*), composes a fragmentary inscription (e. g., VI. 1665 *), imitates the illiterate, as in using the form ongentarius (VI. 2066*), and indulges in such, paleographical novelties as ligatures (e.g., VI. 1657*) or heart-shaped separation points (e.g., VI. 2079*). He carried his work even to the point of carving more than one hundred of his forgeries on stone, most of them for the museum of his patron the Cardinal of Carpi. Some of these have been discussed by Henzen in the Comm. in hon. Mommseni, p. 627 ff. His inscriptions had been suspected by a number of scholars, but their spurious character was first clearly shown by Olivieri at a meeting of a learned society in Ravenna in 1764 (cf. Inscr. Lat. sel., ed. Orelli, I, pp.43-54).

Most of the prolific epigraphical forgers have some idiosyncrasies or some stylistic peculiarities, or they are ignorant in some specific field of the Latin language or of Roman life, and these weaknesses not infrequently betray them. Gutenstein, for instance, in copying an inscription from a previous collector, had the strange habit of making some slight change in a title or a date, as Mommsen has shown in Eph. Epigr. I, p. 71. Thus, for example, he changes pietatis Imperatoris Caesaris [Google translate: the mercy of the Emperor Caesar] to pietati et felieitati imp. Caes., [Google translate: to piety and happiness imp. You kill] and III idus Maias [Google translate: May 3rd] appears in his copy as VI id. Febr., [Google translate: 6 February] although it is impossible to see why he made the alteration. Ligorio's tendencies and the points at which he is ignorant are brought out very clearly by Henzen in Comm. in hon. Mommseni, pp. 627 if. He is weak in the syntax of the cases and not infrequently puts the accusative after the preposition a or ab; he is not familiar with the Roman system of nomenclature and, consequently, confuses nomina and cognomina, gives a slave a nomen, or adds servus to the name of a freedman. His two fads are to put an apex over the preposition a, and to coin titles of the type a potione, to which he is prone to add a word that changes altogether the meaning of these stereotyped expressions; cases in point are faber a Corinthis [Google translate: a carpenter from Corinth], and a balnea custos [Google translate: a bath keeper]. The editors of the Corpus have studied the stylistic characteristics of these two men with such care that Mommsen (op. cit., p. 75) can say with truth: "a Ligorianis autem Gutensteniana qui artem callet non minus certo nec difficilius separabit quam qui poetis Latinis operam dederunt Vergiliana ab Ovidianis distinguunt." [Google translate: But he who is skilled in the art will no less certainly and no more difficultly separate the Gutenstians from the Ligorians than those who have paid attention to the Latin poets distinguish the Virgils from the Ovids.]

The true character of most of the forgeries was not discovered until long after they had been made. In the meantime they were copied into new collections by scholars all over the world, who often failed to indicate the source from which they had borrowed, and one of the most laborious tasks which the editors of the Corpus have had to perform is in tracing an inscription back through manuscript and printed collections to a Lupoli or a Ligorio. Thus VI. 2942*, forged by Ligorio, was borrowed by Panvinius, taken from him by Donius, and finally found its way into Muratori. Not infrequently forgers have been deceived by the inventions of other forgers. Ruggieri published IX. 180* from Mirabella. In the fourth line of Ruggieri's copy stood provo apuliae [Google translate: I stood to try Apulia]. The unscrupulous Pratilli took the inscription from Ruggieri, but changed the two words mentioned to proc. apuliae [Google translate: process Apulia], and finally Lupoli in his collection edited proc. apuliae, but later without comment changed the reading to corr. apuliae [Google translate: corr. Apulia]. The motive which actuated most forgers was a desire to win distinction by the number or importance of their discoveries; some of them wished to prove a point, or to establish the antiquity of their own families. This last motive accounts for Lupoli's invention of IX. 157*: C. Baebius Lu | pulus. et C. Baebius Lupul. f | Silvano. deo | vot. s. 1. m. [Google translate: C. Baebius Lu | flea and C. Baebius Lupul. f | Silvanus god vot s. 1. m.]

It may not be out of place to give a few of the spurious inscriptions which are most interesting in themselves or show a feeling for the picturesque or a sense of. humor on the part of the forger. In VI. 3439* we have the epitaph of Mithradates which reads: Haec est effigies regis | magni Mithradatis divi | tis et summi pauperis et | tenui hic positum horarum | rationes reddere cogit | post obitum nullum | tempus habere doces. [Google translate: This is the portrait of the king the god of the great Mithradates | tis and the most poor and | here is a thin set of hours | compels him to pay his bills after death no | You have time to teach.] The monument which Hannibal set up on the field of Cannae for Paulus Aemilius bore this epitaph: Annibal Pauli Aemilii Romanorum consulis apud Cannas trucidati conquisitum corpus inhumatum iacere passus non est; summo cum honore Romanis militibus mandavit sub hoc marmore reponendum et ossa eius ad urbem deportanda, IX. 99*. [Google translate: Hannibal did not suffer Paulus Aemilius, the Roman consuls at Cannae, to slay the body of the captured body inhumed; with the highest honor he ordered the Roman soldiers to be placed under this marble and his bones to be carried to the city, 9. 99*.] This is the passport which Caesar gave Cicero: C. Caesar M. T. Ciceronem ob egregias eius virtutes singularesque animi dotes per universum orbem virtute nostra armisque perdomitum salvum et incolumem esse iubemus, VI. 81*. [Google translate: C. Caesar M. T. Cicero, because of his excellent virtues and unique gifts of mind, we command to be safe and secure throughout the whole world by our power and weapons, tamed, 6. 81*.] We should have no hesitation in assigning this inscription to Sept. 47 B.C., and we owe its anonymous composer a debt of gratitude for bringing up in so concrete a way the memory of that dramatic meeting of the conqueror and the conquered at Tarentum or Brundisium, at the close of a long year of anxious and frightened waiting -- a meeting of which no other record has survived. The inscription, however, whose spurious character we admit with the greatest reluctance is VI. 3403*, which purports to contain fragments, eleven in all, from the Acta diurna [Google translate: Daily newspaper] of the second and first centuries before our era. The composition seems to go back to the close of the sixteenth century, and is perhaps to be traced to Ludovicus Vives (cf. Heinze De spuriis actorum diurnorum fragmentis) [Google translate: (see Heinze On spurious fragments of newspaper articles)]. It passed unquestioned through the hands of a number of distinguished scholars, Lipsius, Pighius, Camerarius, Graevius, and Vossius, and its authenticity was vigorously defended as late as the middle of the last century. It aroused the special interest of British scholars. John Locke called the attention of Graevius to it about the end of the seventeenth century, and Dodwell devoted himself particularly to its explanation and defense. How cleverly it was composed, so far as content goes, and how valuable it would be, were it authentic, may be illustrated by an extract from the year 586 A.U.C.: IV K. Aprileis fasceis penes Licinium | fulguravit tonuit et quercus tacta in | summa Velia paullum a meridie | rixa ad Ianum infimum in caupona et | caupo ad ursum galeatum graviter | sauciatus | C. Titinius aed. pl. mulcavit lanios | quod carnem vendidissent populo | non inspectam | de pecunia mulcatitia cella exstructa | ad Telluris Lavernae. [Google translate: 4 K. Aprileis fasces near Licinium | it flashed and thundered and the oak touched in | the summa of Velia a little to the south | Argued with Janus at the bottom of the restaurant and | keeper to the helmeted bear heavily | sauciatus | C. Titinius aed. pl. mulcavit lanios | that they had sold the flesh to the people I will not inspect a cell was built with fines to the land of Lavernae.] This whole composition, in fact, is the chef d'oeuvre of the epigraphical forger's art, and reminds one of the missing chapters of Petronius which Nodot cleverly composed and gave to the world a century later.

_______________

Notes:

1 These numbers represent the inscriptions published up to the present time in Vols. II-XIV of the CIL. Vol. I is not included because the inscriptions contained in it are republished elsewhere, and Vol. XV is excluded from the calculation because the spurious inscriptions have not yet been published for that volume. For our purpose it is also unnecessary to take into consideration the published inscriptions which have not yet been included in the CIL.