Percival Chubb and the Founding of the Fabian Society

by Norman MacKenzie

Victorian Studies Vol. 23, No. 1

Autumn 1979

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

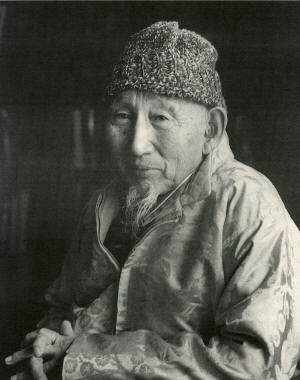

Percival Chubb was a minor star in the Fabian Galaxy, yet he was actually the first and the last of the early Fabians. He survived the octogenarians Sidney and Beatrice Webb and the nonagenerians Bernard Shaw and Edward Pease, dying in 1959 when he was only a year short of his hundredth birthday. It was Chubb who initiated the series of meetings which led to the founding of the Fabian Society on 4 January 1884 and to the complementary foundation of the Fellowship of the New Life. It was also Chubb who served as the link to the wandering philosopher Thomas Davidson, whose eclectic but enthusiastic idealism was nominally the inspiration of both groups. Chubb's part in these events has never been clear, partly because be dropped out of Fabian affairs when he emigrated to the United States in June 1889 and partly because the origins of the Fabian Society itself have never been fully explained. The four most cited historians of the society (Shaw, Pease, Margaret Cole, and A. M. McBriar) did not see the Davidson Collection in Yale University Library, which contains a large number of letters from Chubb and others from William Clarke, Havelock Ellis, and Frank Podmore, and Chubb's own papers have not hitherto been available outside his family.1 Such neglect has done Chubb himself some injustice. More importantly, it has left significant gaps in the record, for Chubb's letters and other papers contain the only detailed account of his relationship with Davidson, of his efforts over several years to promote a practising community of like-minded enthusiasts, and of the complicated discussion which preceded the emergence of the Fabian Society.

Chubb was born on 17 June 1860 in St. Aubyn Street, Devonport. His parents, James and Adelaide Chubb, were Anglicans with an Evangelical bias, and Percival was brought up to strict observance; years of service as a choirboy left him with a habit of hymn singing and a craving for spiritual comfort which persisted long after the faith of his youth had failed him.2 In 1873, James Chubb's modest business failed, and all the family except Percival went off to make a fresh start in Newcastle-on-Tyne. Adelaide Chubb, a woman of somewhat higher social status than her husband, was keen for her eldest son to better himself, and she persuaded her brother, a London printer and bookseller named E. T. Olver, to take the boy into his home and to secure a place for him in the school run by the Stationer's Guild. This was a good foundation; it offered the grammar school curriculum of Greek and Latin, English, history, and geography, with a smattering of science. Chubb did well, winning a prize in each of the three years he spent at the school. At the age of sixteen, he went out to work as a clerk in an import and shipping agency, whose business stimulated his daydreams of emigrating to the New World. He kept up his studies, however, and within twp years he passed the entrance examination for the civil service and became a second-division clerk in the legal department of the Local Government Board.

The post involved much routine drudgery, but the hours of work were relatively short, and there were good holidays besides, Like Sidney Webb, who made a similar move from a colonial broker's office into the Board of Inland Revenue at almost the same time. Chubb disliked the materialism of the commercial world and prized the additional leisure for study that he found in the public service. The salary of £95 It rear, with annual increments of £15, was also an improvement, for Chubb was sorely in need of a few sovereigns to subsidise his family -- his father was a kind but ineffective man who was always struggling on the verge of financial failure -- and to help his growing brothers to some schooling, It was years before Chubb was free of this drain upon his limited income, and it meant that a coveted book had to be bought at the price of a meal, and that the cheapest ticket for a concert was a much calculated extravagance. As Bernard Shaw was discovering as he wandered about London with scarcely a penny to spare, the genteel and clever poor had to search out free entertainment, listening to bands in the park, walking the picture galleries and museum corridors, and going from one meeting to another. These intellectual proletarians, as Shaw called himself and his associates, formed a ready and circulating audience for cranks, reformers, and enthusiasts of all kinds; the tea shop was their club, the British Museum was their library, and the public lecture was their university.

Chubb was an earnest young man who took life seriously and worried at the moral problems it presented. While he lodged with his uncle in Stoke Newington, he attended the local Anglican church of St. Mary's, but soon after he went out to work he had begun the reaction against conventional Christianity that was to carry him through years of agonising doubt to a settled and distinguished place in the Ethical Church movement. As the time for his confirmation approached, he wrote to his mother to say that he could not be confirmed at the hands of an orthodox cleric. "I must have someone of broad views to direct me - if anyone," he wrote, and he suggested that Stopford Brooke, the celebrated minister of the Bedford Chapel who was then about to secede from the Anglican Church, would satisfy his scruples. The general run of clergymen, he insisted, were "at enmity with science, philosophy and, indeed, reason itself .... I repudiate all dogma, and adhere to the maxim that each individual is the best guardian of his own soul"3 These opinions were fostered by the unorthodox preachers he heard when he went sermon-tasting on Sundays, particularly by Stopford Brooke at the Bedford Chapel and the humanist Moncure Conway at South Place, and during the week he pursued other means to self-improvement. From 1879, he went regularly to the meetings of the Aristotelian Society (and, possibly, to the Zetetical Society, where he would have met both Bernard Shaw and Sidney Webb).4 On Wednesday nights he studied Greek and German at the Birkbeck Institute to fit himself to read Plato and Kant in the original, and on Fridays he exercised at a gymnasium. By the end of 1879, his skepticism about conventional religion had reached a point where he felt unable to go with his parents to the midnight service on New Year's Eve, and as an alternative, the family decided to hold an impromptu domestic ceremony which included the reading of elevating texts.5 The change in style exactly exemplified Chubb's shift from faith to spiritual consciousness. "I fail to see a reason for praying," he noted in his diary at the beginning of 1880, "and I was determined to try and make my life one long prayer, prayer in work instead of the formality of prayer as I had been accustomed to it from my earliest years." All the same, Chubb found it depressingly difficult to achieve this ideal condition, and his diary and his letters were punctuated by spasms of self-castigation. "I am unable to realize sufficiently the amount of truth which I feel I possess," he wrote in March 1880. "I cannot embody in my living that which the light which is in me tells me that I ought to ... my enthusiasm runs wastefully over too large and too ill-defined areas."

In this doubtful state of mind, Chubb was understandably eager to find friends with a similar desire for intellectual intimacy as a defence against loneliness, and at the Local Government Board he met several other clerks who shared his taste for philosophy and ethics. One of them was Rowland Estcourt, whom Chubb admired for his flights of utopian fantasy and for his ability to perceive symbolic meanings; another was Hamilton Pullen, a pessimistic agnostic who nevertheless kept up religious appearances to avoid upsetting his family.6 Chubb also had two close friends whom he saw when he visited his family in Newcastle. Ernest Rees (who later changed his name to Rhys and became the editor of the successful Everyman's Library) was then assistant to the manager of a Durham colliery, and Will Dircks, a disciple of Auguste Comte who ardently sought to convert Chubb to Positivism, was to hold a senior post in the Walter Scott publishing company.

In the summer of 1880, with Rees, Dircks, and a couple of other acquaintances who were settled at a distance, Chubb formed the Manuscript Club -- a round robin system of circulating essays and lending books.7 According to the printed card which served as a prospectus, the MS Club was "to design and promote an unconstrained literary fellowship among its scattered members, with the aim of giving some impetus to the pursuit of intellectual culture." It was a modest venture with very grand aims. "Our ultimate object is, I suppose, the construction of a moral ideal, individual and social," Will Dircks wrote on 23 December 1881 in a note reviewing the club's activities during its first year. "It will be allowed that the material of a social reconstruction, is presented in a way that hitherto has not been the case and the problem of arranging the material. the process of reconstruction, is now the question for philosophy, poetic as well as scientific, to undertake."8 In these periphrastic sentences, Dircks stated the two related notions - moral improvement and social reconstruction - which three years later Chubb put before the discussion group which developed into the Fabian Society. Even after Chubb had become an active member of the Fabian Society and of the Fellowship of the New Life, he still felt that there was a place for the kind of dialogue begun in the MS Club, not least because of its context of fraternity. In 1885, in fact, Chubb and the other members made an effort to extend the MS Club into a larger organisation called the Pioneer Club, whose own magazine hoped to appeal to "a rapidly growing minority of young men interested in, and anxious to promote, the free yet serious discussion of literary, philosophical, and social questions generally; young men of fair intellectual equipment, who are living for the most part in isolation from others, of tendencies and tastes similar to their own."9

I

The aspirations of the MS Club. which stressed ethical improvement. a wider culture, and a sense of fellowship, were remarkably close to those of the Progressive Association, founded in 1881 by the Radical publisher John C. Foulger. The Progressive Association was yet another of the crop of new organisations catering to genteel reformers which later led Edward Pease to remark that in the early 1880s London was "full of half-digested ideas." Parlour philosophies were so popular, Pease added, that it seemed "that we should arise one morning and see the old heaven looking down on a new earth."10 The opening words of the first printed circular of the Progressive Association certainly reflected that state of mind. "The Progressive Association," it declared, "is neither theological or anti-theological, but is founded on what is conceived to be the widest workable basis, namely that Man may by his honest efforts promote the highest good and happiness of the human rare on earth."' Foulger was the moving spirit of the association; the journal called Modern Thought, which he published from his City office at 14 Paternoster Row, was intended to serve the same humanist purposes.11 But he had recruited a number of able sympathisers, who used the "Cyprus" tearoom overlooking Cheapside as a weekday meeting place. This group included Havelock Ellis, who was then a medical student at St. Thomas's Hospital and who shared the secretaryship of the association with Foulger; Frank Podmore, a well-educated upper-division clerk in the Post Office who had a sceptical interest in spiritualism and who, in 1882, became one of the founders of the Society for Psychical Research; and Rowland Estcourt, who seems to have introduced Chubb to the association. Chubb soon became an active member, organising the musical entertainments for the Sunday night meetings at a hall in Islington and later helping Ellis to prepare an edition of Hymns for Progress. In 1884, he became a member of the association's executive and took the place of Ellis as joint secretary.

There is a strong family resemblance, a likeness that suggests direct inheritance, between the aims and means of the association and the original purposes of the Fabian Society, which was formed just over two years later. At least ten members of the association were present at one or more of the informal talks which preceded its formation - Rev. George Alien, Dr. Burns-Gibson, Henry Hyde Champion, Chubb, Ellis, Estcourt, Foulger, Miss Haddon, Mrs. James Hinton, and Podmore. The aims looked for social progress based upon "honesty and sympathy and mutual trust," and the means for achieving this improved state of affairs were divided into five categories. There were to be lectures and meetings "devoted largely to questions of human conduct, and the advancement of man's condition and ideal." There were to be campaigns for improved housing and other sanitary measures and for "advances in Physical, Mental and Moral Education, including an extended knowledge of the Laws of Life, Temperance, the opening of Free Art Exhibitions, Reading Rooms and Libraries." The association also proposed to prepare and distribute pamphlets, to support parliamentary measures which it approved and to oppose those it disliked, and to "run classes of an attractive kind" for young people "to teach such views of life as will make them worthy citizens of their own, and fit parents of the next generation." With such lofty aims and means, the association was a congenial meeting place for those who, like Chubb, believed that people must be moralised before they would be capable of building the Ideal City.12

In any event, however, the association became little more than a very mixed set of Sunday-go-to-meeting people who came to sing humanist hymns, listen to uplifting poetry and prose, and applaud a comparably mixed set of lecturers. In the course of 1882, the list included Henry Crompton on "Buddhism and Positivism," E. Belfort Bax on "Karl Marx," Henry Hyde Champion on "Poets of the Revolution," William Morris on "Art and Democracy," two talks apiece by H. M. Hyndman and Thomas Davidson, Helen Taylor (the stepdaughter of John Stuart Mill who had assisted Henry George on his 1882 visit to Britain ) on "Land Nalionalisation," J. L. Joynes on "Adventures in Ireland" (where he and George had recently been arrested in an incident which gave George and his Progress and Poverty a sudden notoriety), and a scattering of other speakers on the woman question, workhouses, food reform, and sundry literary topics.

The neophyte Marxists from the Democratic Federation, especially Bax, Morris, Hyndman, and Joynes, clearly made an impact on the association, for its annual report for 1882-83 - the winter when the socialist revival was beginning to gather momentum - shows that "some members" wanted the association '"to take up a more defined attitude towards questions of Social Reform," and a motion to that effect was put at one of the semiformal meetings which were a regular part of the Sunday gatherings. This lengthy text, pressing the socialist case while carefully making concessions to the sensibilities of moral force reformers, seems to reveal the hand of Champion. always a busy draftsman, always a nimble tactician, and always willing to concede a theoretical point to placate an ally.

While believing in the necessity for social reconstruction, the Progressive Association considers that such reconstruction, to be either permanent or beneficial, must proceed by only such revolutionary means as are consistent with the natural development of the community, and that social development can only advance side by side with individual development. The Association looks for a more equable distribution of labour and wealth, thus placing within the reach of all classes (and doing injustice to no class) the attainment of the full development of individual activities. It will therefore be prepared to support measures for bringing the means of production within the control of the community, and for the organization of labour, both by the State and in the form of Co-operation. As a preparation for these Social changes the Association will support compulsory education, moral, physical and intellectual (including technical education) and seeks by voluntary efforts to spread information regarding all Social subjects.

The resolution, which was not actually put in order "to give further opportunities for the consideration and discussion of Social questions," remains an intriguing fusion of ideas which were later to be sharply differentiated - a point made by Hubert Bland in his contribution to Fabian Essays. "When I first called myself a Socialist," he wrote, "I had all sorts of hopes and aspirations. I seemed to think [it] a widely inclusive term which embraced anything I particularly wanted. And what was true of myself, I noted, was true of others."13 At the end of 1882, the new socialist movement was still so conceptually confused that these few sentences could be equally supported by such future luminaries of the Social Democratic Federation as Champion, R. P. B. Frost, Joynes, and Helen Taylor, by a thoroughgoing Radical like Foulger, by an old Chartist and freethinker like George Holyoake, and by earnest young moralists like Chubb, Estcourt, and ElIis.14 The debate on the issues raised by that resolution rail on all through 1883, apparently without rancour and also without much theoretical finesse, for in the early autumn of 1883, Chubb felt no hesitation in inviting several of "the fellows" who were in Hyndman's camp (Bax, Champion, Frost, and Joynes) to discuss his scheme for founding an ethical brotherhood.

Chubb was an enthusiastic and somewhat indiscriminate joiner; all through 1883 he vacillated between the urge to withdraw from a stressful and corrupt world into a "spiritual" community and the attractions of the "worldly" socialist movement. "I can scarcely say what predominates in me," he wrote on 1 April 1883, "the passion for self-perfection, the desire to attain true manhood, to get a sure hold on life, or the humanitarian ardour ... to aid in the realisation of the social Utopia."15 He was clearly an impressionable youth, eager but unsure of himself, and given to deferring to stronger personalities. What he needed was a mentor, someone who would be a spring of affection, intellectual stimulation, and moral guidance as he sought to find a settled identity among the confusions of late adolescence. In the autumn of 1881 at a meeting of the Aristotelian Society at which he was giving his first public talk (on "The Ethics of Plato"), Chubb met such a man in the person of Thomas Davidson.16

II

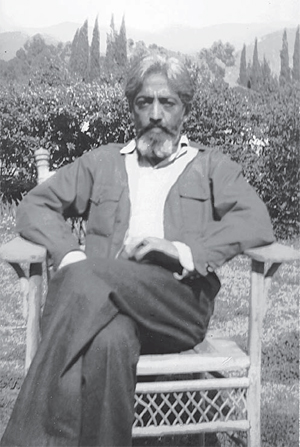

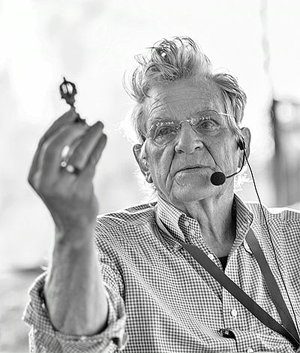

This free-lance scholar, the illegitimate son of a Scottish shepherd, was then 43, and in the years after his graduation from King's College, Aberdeen, where he discovered a brilliant gift for languages and philosophy, Davidson had found a settled life so distasteful to his independent nature that he had wandered irresolutely between the New World and the Old. The transcendentalists of Massachusetts had contributed as much as the Greek and Roman philosophers to his eclectic idealism, and he eventually established his own rural retreat at Glenmore, in the Adirondacks. William James, who knew him well when he lived in Boston, considered him an attractive man with "a genius for friendship," who was "ready to give his soul to aspiring young men as if he had nothing else to do with it ."17 This Hellenic trait made an immediate appeal, not least because Davidson was a wonderful and ideologically seductive talker. Havelock Ellis, recalling his first meeting with Davidson, said that he was a "really remarkable man ... be was alive, intensely and warmly alive, as even his complexion and colouring seemed to show; here was the perfervid Scottish temperament carried almost or quite to the point of genius."18 Yet there was another and less attractive side to Davidson. He was dominating and contumacious, convinced that whatever opinion he currently held was the truth, and he denounced error in others with all the zeal of his Presbyterian youth. When William James tried to secure him an appointment at Harvard. for instance, he wrecked his chances by savagely and gratuitously attacking the teaching methods of the Greek department in the pages of the Atlantic Monthly. His apparent confidence, James concluded, was a mask for fits of "motiveless nervous dread," his flow of noble rhetoric dried into peevishness when he was piqued, and he was jealous and possessive. Although Chubb was proud of his brilliant friend and extolled Davidson's virtues to his acquaintances, he found the relationship of master and acolyte a continuing source of anxiety; their correspondence was punctuated by Davidson's demands for loyalty and Chubb's nervous apologies for his shortcomings, and on several occasions. Chubb was embarrassed by Davidson's haughty attitude to other people.

In 1881 Davidson was preaching a narcissistic faith in personal perfectibility, to be achieved in the context of a fellowship, or a secular monastic order. This doctrine of a spiritual elite owed something to Comte - though Davidson was always scornful of Positivists - and something to the metaphysics of St. Thomas. but it was more directly inspired by the teachings of an early nineteenth-century Catholic philosopher named Antonio Rosmini-Serbati, who had held a post in the Vatican before his developing ideas brought him under charges of heresy. A Rosiminian community, the Institute of Charity, had in fact survived at Domodossola, in the foothills of the Alps near Lake Como, and Davidson stayed there several times to study and translate the writings of its founder. As soon as Chubb heard of the Rosiminian doctrine of the Vita Nuova - the idea that a man might apprehend and exemplify the divine within himself - he was much taken by its resemblance to his own intense but unsophisticated commitment to self-perfection; it seemed, indeed, to be a metaphysical restatement of the Evangelical doctrine of the open, unselfish life as the means to spiritual sensibility. After Davidson had gone back to Domodossola at the end of 1881, Chubb sent him a series of letters which served as a release for his moods of "discontent with the meagreness and falsity of life" as a poor clerk in London and gave him a chance to confess his aspirations to an older sympathiser.19

In the early months of this friendship, Chubb wrote a good deal about his own troubles and about his friends Rees and Dircks. The three young men had already toyed with the notion of establishing a literary colony in the Lake District - a scheme which seems to have owed much to their interest in William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Robert Southey. "We were to work our way into the literary world," Chubb told Davidson on 25 May 1882, "and when able to earn enough to support ourselves, to retire into seclusion for culture and the founding of a revolutionary organisation such as we hope our little Club recently started may develop into. There, we said, should be the centre of a general regenerating movement . . . our proposal did not compass the larger and, as I now think, more effective scheme for the formation of a Utopian State. We had seen the Brook Farm failure, and that perhaps checked our thoughts in this direction." A small band of friends, so prone to utopianism as to have such daydreams about their literary colony and their MS Club, were unlikely to balk at Davidson's even grander vision of converting the world "from evil to good, from darkness to light, from misery to blessedness."

In the summer of 1882, Chubb went out to stay with Davidson at Domodossola, and on this first and exciting visit to Europe - demanding the utmost economy because his father was once again in financial trouble and the family had turned to the eldest son for help - mentor and acolyte talked optimistically of a plan to transplant the New Life from the sunny Italian hillside to what Chubb called the dirt, din, and disorder of London. Soon after Chubb returned home, Davidson followed him, Slopping in the metropolis for a few days on his way to see his mother in Scotland. Chubb had already spoken hopefully to his friends about Davidson's arrival. Havelock Ellis, who often shared a "slight lunch at a pastrycook's" with Chubb. recalled the day when Chubb invited him to meet this "great ethical leader who sought to renew the life of society on a loftier plane" ( Ellis. p. 159). Chubb also introduced Davidson to Estcourt and Pullen, and to William Clarke, a talented hut misanthropic journalist who was a fellow member of the Aristotelian Society.20 At the Progressive Association. where Chubb may have arranged the invitation for Davidson to speak on "The Methods of Progress" on 9 September, Davidson apparently met Foulger, Champion, Podmore, Burns-Gibson, Allen. and a transcendentally minded Congregational minister named W. J. Jupp. who lived in the suburban village of Thornton Heath, near Croydon.21

Chubb wished to follow up these casual encounters with a more formal meeting at which Davidson would expound his concept of the New Life, and Davidson was overtly encouraging. "What a delightful thing it would be for me if we could have the first meeting of the Eutopians on my birthday, which is next Wednesday," he wrote to Chubb from Scotland on 19 October 1882. "I should feel I was really beginning a New Life." In fact, Davidson felt that Chubb was forcing the pace and that several of the men he had met in London were unsympathetic or actually opposed to his metaphysical system; he therefore made a guarded offer of little more than his patronage.22 "I wish from my heart," he told Chubb, "that I could remain in England for a year or two in order to cooperate with you and your friends in laying the basis for a New Life Edifice." Four days later, he wrote to tell Chubb to cancel the proposed meeting and to do nothing "about our scheme" until everything was settled. "The fait accompli has considerable effect. And then we cannot begin with determinists or pessimists. We must have free men and optimists of the first water -- men without caution, men full of faith, hope, love and enthusiasm. Quality not quantity at first."

What Davidson called "our scheme," first discussed when Chubb went to Domodossola, was extremely vague. This may be another reason for his reluctance to confront possible recruits, for as late as 7 October, when Chubb was planning his meeting of "Eutopians," he had nothing more to send Davidson than some scrappy headings. These notes may have been worked up into something more substantial before Davidson left London in November, but Chubb certainly continued to work at an outline of the scheme, for on 27 December he reported to Davidson that he was working on the New Life programme during his Christmas holidays. The subsequent correspondence with Davidson shows that all through 1883, Chubb was working without an agreed text to show to interested parties.23 In his letter of 27 December, for instance, Chubb reported a talk with Belfort Bax after a meeting of the Aristotelian Society in which Bax treated the Chubb-Davidson plan "rather as an interesting experiment than as something which affords scope for latent longings and pent-up aspirations." Chubb, a victim to Weltschmerz and much given to romantic phrases, was no man to translate Davidson's abstract thought into a practical scheme which would impress such a recently converted Marxist as Bax; he found it more congenial to work hard at German, Greek, Italian, and philosophy than at the worldly task of organisation.

Chubb had a number of personal perplexities to distract him during the spring and summer of 1883. He reported to Davidson that a married woman had made him an offer of financial help in exchange for an emotional union and that he had unsuccessfully wrestled with this temptation. He also consulted Davidson about his future - whether he should attempt to enter Aberdeen University or emigrate to St. Louis with Davidson, who was talking of going to America later in the year. Such uncertainties were one reason why he did so little to promote the fellowship plan for several months; another reason, as he confessed to Davidson on 10 March 1883, was the difficulty of keeping his mind on the lofty goals of the New Life when there were so many voices around him talking of a new social order. "Les maladies du siecle press heavily upon me," he wrote, "and the struggle of the hour, the spectacle of the peoples awakening to the consciousness of higher things, are strangely moving. How Europe begins to vibrate with the onward march of her oppressed and aroused children. It is indeed hard to remain quiet; but I shall restrain myself."

Like many of his associates, Chubb had been affected by the visit of Henry George to England in 1882, and during his Christmas visit to his family he had gone down into the Durham coalfield at the invitation of Rees to speak on Progress and Poverty to a group of miners. By the beginning of May 1883, he was aware that some socialists and Georgeites of his acquaintance were planning a new organisation. "There is much going on here on the way of reformatory movement to keep me on the alert," he told Davidson on 2 May. "Something must be done, some new step taken; and I myself am itching to be doing something, I know that you counsel patience and waiting, and no doubt success is impossible without these. But if you were moving amidst this scene of degradation and misery, and with the full consciousness that next to nothing is being done to remedy it, your soul would ache, and you would be chafed into rebellion," One way of creating a new way of life, Chubb suggested, would be to establish communities of craftsmen, basing themselves on Ruskin's statement of principle to the St. George's Guild, but he was aware of the weakness of a notion widely canvassed by ethical socialists. Where would he and his like, raised by an artificial civilisation to be town- dwelling clerks, acquire the necessary skills to make and mend and to reap and sow? It might be better, he told Davidson, to search for a way of combining ethical and political purposes, and on 24 May, reporting the formation of the Land Reform Union and the launching of the Christian Socialist, he said that the new paper was "the child of a group of young men who are ardent disciples of George, Marx, and the revolutionary luminaries, and are trying to enforce their ideas by claiming that they receive teh sanction of Jesus and the primitive Christians."24 He was himself so affected by this new mood that he was "deep in Political Economy, Socialism, Land Reform, and so on."

Davidson. now staying in Capri after a winter in Home, reacted sharply. He had already told Chubb on 31 March that "a lingering fondness for the Christian myth" was the great obstacle to the new ethical movement he wished to promote, and the claims of the Christian Socialist annoyed him; he clearly feared that Chubb was backsliding into social activism (and his anxieties in this respect were undoubtedly increased when William Clarke wrote on 8 June 1883 to confirm that Chubb was now "a strong socialist"). "If Socialism is right," Davidson replied to Chubb, "it ought to do the manly thing and stand on its own feet and not crouch under the cross of an ancient miracle-monger .... Let us stick to our own little programme, and work it out slowly ... leave watchwords for those who wish for ephemeral success." Thus reproved, Chubb said little more about his political interests, and his letters throughout the summer dealt mainly with his personal problems and his plans for a walking holiday in Normandy. There was only a passing reference to "the possibility of a select conference in the autumn" in a letter written on 21 July.

It was Davidson's return to London in September that revived Chubb's interest, for it gave him another chance to bring a group of his friends together to discuss the New Life project. But this was not easy, partly because Davidson insisted on his own metaphysical system and partly because he was condescendingly intolerant of those who had different opinions. On 2 October, at one of the informal meetings which Chubb arranged to introduce Davidson to possible sympathisers, Davidson found himself at odds with Havelock Ellis, and on the following day he sent Ellis a letter to summarise his philosophy. "The fact is that there can never be any positive basis (in our little programme) but a metaphysical one, for the simple reason that all abiding reality is metaphysical; that is to say lies behind the physical or sensuously phenomenal," The discussion on the previous evening, Davidson added, "at once confirmed me in the need for community, and showed clearly some of the most formidable difficulties in the way of such a thing; the want of a spiritual light; the childish prejudice against metaphysics" (Knight, p. 38). Chubb certainly assumed that the New Life scheme implied the founding of a community of some kind. While he took a simple view of Davidson's complex intellectual system - in a letter written on 17 November he made the revealing admission that some of his friends "exhibit a kind of discomfort" whenever Davidson's metaphysics were mentioned - he clearly thought Davidson a prestigious sponsor whose teachings would give the tone of a higher culture to his utopian project for a fraternity. Despite the signs of disagreement, he therefore hopefully pressed on with his plans and persuaded Edward Pease (whom Podmore had brought to the meeting on 2 October) to be the host to an invited company which would meet at his comfortable lodgings in 17 Osnaburgh Street, Regent's Park, on the evening of Wednesday, 24 October 1883.