Robert Thurman [Bob Thurman] [Alexander Thurman] [Alecsander Thermen]

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 6/29/20

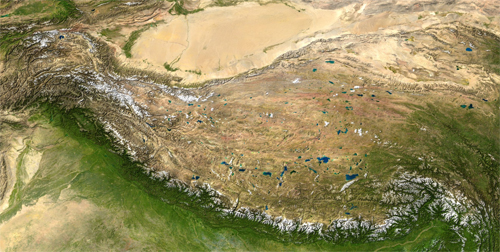

The Kalachakra temple in St. Petersburg

There is a simple reason for Dorjiev’s enthusiasm for Russia. He was convinced that the Kalachakra system and the Shambhala myth had their origins in the Empire of the Tsar and would return via it. In 1901 the Buriat had received initiations into the Time Tantra from the Ninth Panchen Lama which were supposed to have been of central significance for his future vision. Ekai Kawaguchi, a Buddhist monk from Japan who visited Tibet at the turn of the last century, claims to have heard of a pamphlet in which Dorjiev wrote “Shambhala was Russia. The Emperor, moreover, was an incarnation of Tsongkhapa, and would sooner or later subdue the whole world and found a gigantic Buddhist empire” (Snelling, 1993, p. 79). Although it is not certain whether the lama really did write this document, it fits in with his religious-political ideas. Additionally, the historians are agreed: “In my opinion,” W.A. Unkrig writes, “the religiously-based purpose of Agvan Dorjiev was the foundation of a Lamaist-oriented kingdom of the Tibetans and Mongols as a theocracy under the Dalai Lama ... [and] under the protection of Tsarist Russia ... In addition, among the Lamaists there existed the religiously grounded hope for help from a ‘Messianic Kingdom’ in the North ... called 'Northern Shambhala’” (quoted by Snelling, 1993, p. 79).

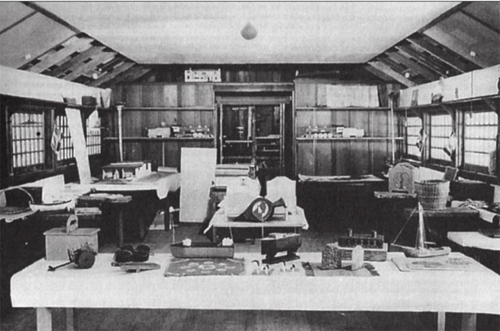

At the center of Dorjiev’s activities in Russia stood the construction of a three-dimensional mandala — the Buddhist temple in St. Petersburg. The shrine was dedicated to the Kalachakra deity. The Dalai Lama’s envoy succeeded in bringing together a respectable number of prominent Russians who approved of and supported the project. The architects came from the West. A painter by the name of Nicholas Roerich, who later became a fanatic propagandist for Kalachakra doctrine, produced the designs for the stained-glass windows. Work commenced in 1909. In the central hall various main gods from the Tibetan pantheon were represented with statues and pictures, including among others Dorjiev’s wrathful initiation deity, Vajrabhairava. Regarding the décor, it is perhaps also of interest that there was a swastika motif which the Bolsheviks knocked out during the Second World War. There was sufficient room for several lamas, who looked after the ritual life, to live on the grounds. Dorjiev had originally intended to triple the staffing and to construct not just a temple but also a whole monastery. This was prevented, however, by the intervention of the Russian Orthodox Church.

The inauguration took place in 1915, an important social event with numerous figures from public life and the official representatives of various Asian countries. The Dalai Lama sent a powerful delegation, “to represent the Buddhist Papacy and assist the Tibetan Envoy Dorjiev” (Snelling, 1993, p. 159). Nicholas II had already viewed the Kalachakra temple privately together with members of his family several days before the official occasion.

Officially, the shrine was declared to be a place for the needs of the Buriat and Kalmyk minorities in the capital. With regard to its occult functions it was undoubtedly a tantric mandala with which the Kalachakra system was to be transplanted into the West. Then, as we have already explained, from the lamas’ traditional point of view founding a temple is seen as an act of spiritual occupation of a territory. The legends about the construction of first Buddhist monastery (Samye) on Tibetan soil show that it is a matter of a symbolic deed with which the victory of Buddhism over the native gods (or demons) is celebrated. Such sacred buildings as the Kalachakra temple in St. Petersburg are cosmograms which are — in their own way of seeing things — employed by the lamas as magic seals in order to spiritually subjugate countries and peoples. It is in this sense that the Italian, Fosco Maraini, has also described the monasteries in his poetic travelogue about Tibet as “factories of a holy technology or laboratories of spiritual science” (Maraini, 1952, p. 172). In our opinion this approximates very closely the Lamaist self-concept. Perhaps it is also the reason why the Bolsheviks later housed an evolutionary technology laboratory in the confiscated Kalachakra shrine of St. Petersburg and performed genetic experiments before the eyes of the tantric terror gods.

The temple was first returned to the Buddhists in June 1991. In the same year, a few days before his own death, the English expert on Buddhism, John Snelling, completed his biography of the god-king’s Buriat envoy. In it he poses the following possibility: “Who knows then but what I call Dorjiev's Shambhala Project for a great Buddhist confederation stretching from Tibet to Siberia, but now with connections across to Western Europe and even internationally, may well become a very real possibility” (Snelling, 1993, xii). Here, Snelling can only mean the explosive spread of Tantric Buddhism across the whole world.

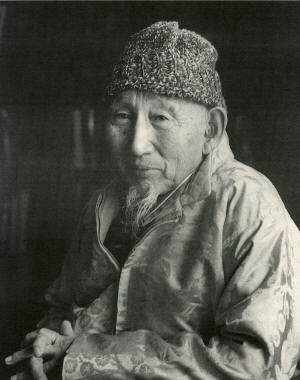

If we take account of the changes that time brings with it, then today the Kalachakra temple in Petersburg would be comparable with the Tibet House in New York. Both institutions function(ed) as semi-occult centers outwardly disguised as cultural institutions. In both instances the spread of the Kalachakra idea is/was central as well. But there is also a much closer connection: Robert Alexander Farrar Thurman, the founder and current leader of the Tibet House, went to Dharamsala at the beginning of the sixties. There he was ordained by the Dalai Lama in person. Subsequently, the Kalmyk, Geshe Wangyal (1901-1983), was appointed to teach the American, who today proclaims that he shall experience the Buddhization of the USA in this lifetime. Thurman thus received his tantric initiations from Wangyal.

This guru lineage establishes a direct connection to Agvan Dorjiev. Namely, that as a 19-year-old novice Lama Wangyal accompanied the Buriat to St. Petersburg and was initiated by him. Thus, Robert Thurman’s “line guru” is, via Wangyal, the old master Dorjiev. Dorjiev — Wangyal — Thurman form a chain of initiations. From a tantric viewpoint the spirit of the master live on in the figure of the pupil. It can thus be assumed that as Dorjiev’s “successor” Thurman represents an emanation of the extremely aggressive protective deity, Vajrabhairava, who had incarnated himself in the Buriat. At any rate, Thurman has to be associated with Dorjiev’s global Shambhala utopia. His close interconnection with the Kalachakra Tantra is additionally a result of his spending several months in Dharamsala under the supervision of Namgyal monks, who are specialized in the time doctrine...

We have described often enough the political goal of this much-admired religious movement. It involves the establishment of a global Buddhocracy, a Shambhalization of the world, steered and governed, where possible, from Potala, the highest “Seat of the Gods” From there the longed-for Buddhist world ruler, the Chakravartin, ids supposed to govern the globe and its peoples. Of course, His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama would never speak so directly about this vision. But his prophet in the USA, Robert Thurman, is less circumspect.

Robert A. Thurman: “the academic godfather of the Tibetan cause”

Robert Alexander Farrar Thurman, the founder and current head of the Tibet House in New York, traveled to Dharamsala in the early 1960s. There he was introduced to the Dalai Lama as “a crazy American boy, very intelligent, and with a good heart” who wanted to become a Buddhist monk. The Tibetan hierarch acceded to the young American’s wish, ordained him as the first Westerner to become a Tibetan monk, and personally supervised his studies and initiatory exercises. He considered Thurman’s training to be so significant that he required a weekly personal meeting. Thurman’s first teacher was Khen Losang Dondrub, Abbot of the Namgyal monastery which was specifically commissioned to perform the so-called Kalachakra ritual. Later, the Kalmyk Geshe Wangal (1901–1983) was appointed as teacher of the “crazy” American (born 1941), who today maintains that he will be able to celebrate the Buddhization of the USA within his lifetime.

Having returned from India to the United States, Thurman began an academic career, studying at Harvard and translating several classic Buddhist texts from Tibetan. He then founded the “Tibet House” in New York, a missionary office for the spread of Lamaism in America disguised as a cultural institute.

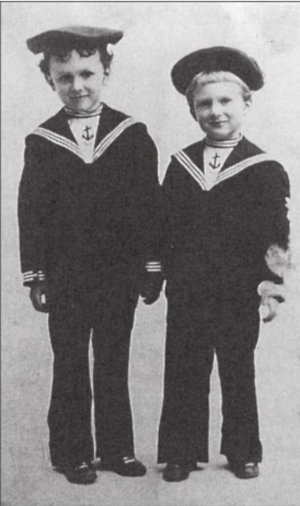

Alongside the two actors Richard Gere and Steven Segal, Thurman is the crowd puller of Tibetan Buddhism in the USA. His famous daughter, the Hollywood actress Uma Thurman, who as a small child sat on the lap of the Tibetan “god-king”, has made no small contribution to her father’s popularity and opened the door to Hollywood celebrities. The Herald Tribune called Thurman “the academic godfather of the Tibetan cause” (Herald Tribune, 20 March 1997, p. 6) and in 1997 Time magazine ranked him among the 25 most influential opinion makers of America. He is described there with a telling ironic undertone as the “Saint Paul or Billy Graham of Buddhism” (Time, 28 April 1997, p. 42) Thurman is in fact extremely eloquent and understands how to fascinate his audience with powerful polemics and rhetorical brilliance. For example, he calls the Tibetans “the baby seals of the human right movement”.

In the Shugden affair, Thurman naturally took the side of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama and proceeded with the most stringent measures against the “sectarians”, publicly disparaging them as the “Taliban of Buddhism”. When three monks were in stabbed to death in Dharamsala he saw this murder as a ritual act: “The three were stabbed repeatedly and cut up in a way that was like exorcism” (Newsweek, 5 May 1997, p. 43).

Thurman is the most highly exposed intellectual in the American Tibet scene. His profound knowledge of the occult foundations of Lamaism, his intensive study of Tibetan language and culture, his initiation as the first Lamaist monk from the western camp, his rhetorical brilliance and not least his close connection to the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, which is more than just a personal friendship and rests upon a religious political alliance, all make this man a major figure in the Lamaist world. The American is — as we shall see — the exoteric protagonist of an esoteric drama, whose script is written in what is known as the Kalachakra Tantra. He promotes a “cool revolution of the world community” and understands by this “a cool restoration of Lamaist Buddhism on a global scale”.

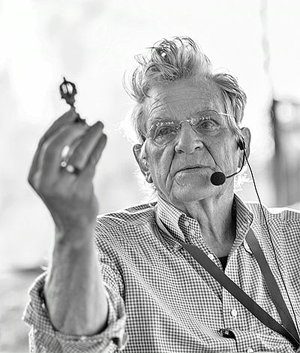

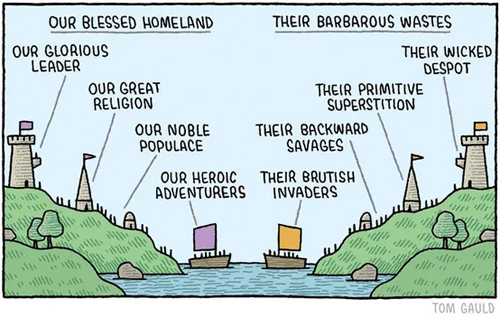

We met Robert Thurman in person at a Tibet Conference in Bonn (“Myth Tibet” in 1996). He was without doubt the most prominent and theatrical speaker and far exceeded the aspirations laid out by the conference. The organizers wanted to launch an academically aseptic discussion of Tibet and its history under the motto that our image of Tibet is a western projection. In truth, Tibet was and is a contradictory country like any other, and the Tibetans like other peoples have had a tumultuous history. The image of Tibet therefore needs to be purged of any occultism and one-sided glorification. Thus the most well-known figures of modern international Tibetology were gathered in Bonn. The proceedings were in fact surprisingly critical and an image of Tibet emerged which was able to peel away some illusions. There was no more talk of a faultless and spiritual Shangri-La up on the roof of the world.

Despite this apparently critical approach, the event must be described as a manipulation. First of all, the cliché that the West alone is responsible for the widespread image of Tibet found here was reinforced. We have shown at many points in our book that this blissful image is also a creation of the lamas and the Fourteenth Dalai Lama himself. Further, the fact that Lamaism possesses a world view in which western civilization is to be supplanted via a new Buddhist millennium and that it is systematically working towards this goal was completely elided from the debate in Bonn. It appears the globalizing claims of Tibetan Buddhism ought to be passed over silently. At this conference Tibet continued to be portrayed as the tiny country oppressed by the Chinese giant, and the academics, the majority of whom were practicing Buddhists, presented themselves as committed ethnologists advocating, albeit somewhat more critically than usual, the rescue of an endangered culture of a people under threat. By and large this was the orientation of the conference in Bonn. It was hoped to create an island of “sober” scholarliness and expertise in order to inject a note of realism into the by now via the media completely exaggerated image of Tibet — in the justifiable fear that this could not be maintained indefinitely.

This carefully considered objective of the assembled Tibetologists was demolished by Thurman. In a powerfully eloquent speech entitled “Getting beyond Orientalism in approaching Buddhism and Tibet: A central concept”, he sketched a vision of the Buddhization of our planet, and of the establishment of a worldwide “Buddhocracy”. Here he dared to go a number of steps further than in his at that stage not yet published book, Inner Revolution. The quintessence of his dedicated presentation was that the decadent, materialistic West would soon go under and a global monastic system along Tibetan lines would emerge in its stead. This could well be based on traditional Tibet, which today at the end of the materialistic age appears modern to many: “Three hundred years before, this is the time, what I called modern Tibet, which is the Buddhocratic, unmilitaristic, mass-monastic society …” (Thurman at the conference in Bonn).

Such perspectives clearly much irritated the conference organizers and immensely disturbed their ostensible attempt to introduce a note of academic clarity. The megalomaniac claims of Tibetan neo-Buddhism plainly and openly forced their way into the limelight during Thurman’s speech. A spectacular row with the officials resulted and Thurman left Bonn early.

Irrespective of one’s opinion of Thurman, his speech in Bonn was just plain honest; it called a spade a spade and remains an eminently important record since it introduced the term “Buddhocracy” into the discussion as something desirable, indeed as the sole safety anchor amid the fall of the Western world. Those who are familiar with the background to Lamaism will recognize that Thurman has translated into easily understood western terms the religious political global pretensions of the Tibetan system codified in the Kalachakra Tantra. The American “mouthpiece of the Dalai Lama” is the principal witness for the fact that a worldwide “Buddhocracy” is aspired to not just in the tantric rituals but also by the propagandists of Tibetan Buddhism. Thurman probably revised and tamed down his final manuscript for Inner Revolution in light of events in Bonn. There, the emotive terms Buddhocracy and Buddhocratic are no longer so central as they were in his speech in Bonn. Nonetheless a careful reading of his book reveals the Buddhocratic intentions are not hidden in any way. In order to more clearly give prominence to these intentions, however, we will review his book in connection with his speech in Bonn.

The stolen revolution

Anybody who summarizes the elements of the political program running through Thurman’s book Inner Revolution from cover to cover will soon recognize that they largely concern the demands of the “revolutionary” grass roots movement of the 70s and 80s. Here there is talk of equality of the sexes, individual freedom, personal emancipation, critical thought, nonconformity, grass roots democracy, human rights, a social ethos, a minimum income guaranteed by the state, equality of access to education, health and social services for all, ecological awareness, tolerance, pacifism, and self-realization. In an era in which all these ideas no longer have the same attraction as they did 20 years ago, such nostalgic demands are like a balsam. The ideals of the recent past appear to have not been in vain! The utopias of the 1960s will be realized after all, indeed, according to Thurman, this time without any use of violence. The era of “cool revolution” has just begun and we learn that all these individual and social political goals have always been a part of Buddhist cultural tradition, especially Tibetan-style Lamaism.

With this move, Thurman incorporates the entire set of ideas of a protest generation which sought to change the world along human-political lines and harnesses it to a Tibetan/Buddhist world view. In this he is a brilliant student of his smiling master, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama. Tens of thousands of people in Europe and America (including Petra Kelly and the authors) became victims of this skillful manipulation and believed that Lamaism could provide the example of a human-politically committed religion. Thousands stood up for Tibet, small and oppressed, because they revered in this country a treasure trove of spiritual and ethical values which would be destroyed by Chinese totalitarianism. Tibetan Buddhism as the final refuge of the social revolutionary ideals of the 70s, as the inheritance of the politically involved youth movement? This is — as we shall show — how Lamaism presents itself in Thurman’s book, and the Fourteenth Dalai Lama gives this interpretation his approval. “Thurman explained to me how some Western thinkers have assumed that Buddhism has no intention to change society ... Thurman’s book provides a timely correction to any lingering notions about Buddhism as an uncaring religion.” (Thurman1998, p. xiii)

But anyone who peeps behind the curtains must unfortunately ascertain that with his catalog of political demands Thurman holds a mirror up to the ideals of the “revolutionary” generation of the West, and that he fails to inform them about the reality of the Lamaist system in which used to and still does function along completely contrary social political lines.

Thurman’s forged history

In order to prevent this abuse of power becoming obvious, the construction of a forged history is necessary, as Thurman conscientiously and consistently demonstrates in his book. He presents the Tibet of old as a type of gentle “scholarly republic” of introspective monks, free of the turbulence of European/imperialist politics of business and war. In their seclusion these holy men performed over centuries a world mission, which is only now becoming noticeable. Since the Renaissance, Thurman explains, the West has effected the “outer modernity”, that is the “outer enlightenment” through the scientific revolution. At the same time (above all since the rule of the Fifth Dalai Lama in the seventeenth century) an “inner revolution” has taken place in the Himalayas, which the American boldly describes as “inner modernity”: “So we must qualify what we have come to call ‘modernity’ in the West as ‘materialistic’ or ‘outer’ modernity, and contrast it with a parallel but alternative Tibetan modernity qualified as ‘spiritualistic’ or ‘inner’ modernity” (Thurman 1998, p. 247). At the 1996 conference in Bonn he did in fact refer to the “inner modernization of the Tibetan society”.

Committed Buddhism, according to Thurman, is instigating a “cool revolution” (in the sense of ‘calm’).It is “cool” in contrast to the “hot” revolutions of the Western dominated history of the world which demanded so many casualties. The five fundamental principles of this “cool revolution” are cleverly assigned anew to a Western (and not Oriental) system of values: transcendental individualism, nonviolent pacifism, educational evolutionism, ecosocial altruism, universal democratism.

For Thurman, the Tibetan culture of “sacralization”, “magic”, “enlightenment”, “spiritual progress”, and “peaceful monasticism” stands in opposition to a Western civilization of “secularization”, “disenchantment”, “rationalization”, “profane belief in material progress”, and “materialism, industrialism, and militarism” (Thurman 1998, p. 246).Even though the “inner revolution” is unambiguously valued more highly, the achievements of the West ought not be totally abandoned in the future. Thurman sees the world culture of the dawning millennium in a hierarchical (East over West) union of both. Upon closer inspection, however, this “cool revolution” reveals itself to be a “cool restoration” in which the world is to be transformed into a Tibetan-style Buddhist monastic state.

To substantiate Lamaism’s global mission (the “cool revolution”) in his book, Thurman had to distort Tibetan history, or the history of Buddhism in general. He needed to construct a pure, faultless and ideal history which from the outset pursued an exemplary, highly ethical task of instruction, aimed to culminate eschatologically in the Buddhization of the entire planet. The Tibetan monasteries had to be portrayed as bulwarks of peace and spiritual development, altruistically at work in the social interests of all. The image of Tibet of old needed to appear appropriately noble-minded, “with”, Thurman says, “the cultivation of scholarship and artistry; with the administration of the political system by enlightened hierarchs; with ascetic charisma diffused among the common people; and with the development of the reincarnation institution. It was a process of the removal of deep roots in instinct and cultural patterns” (Thurman 1998, p. 231). A general misrepresentation in Thurman’s historical construction is the depiction of Buddhist society and especially Lamaism as fundamentally peaceful (to be played out in contrast to the deeply militaristic West): “[T]he main direction of the society was ecstatic and positive; intrigues, violence and persecution were rarer than in any other civilization” (Thurman 1998, p.36). Although appeals may be made to relevant sutras in support of such a pacifist image of Tibetan Buddhism, as a social reality it is completely fictive.

As we have demonstrated, the opposite is the case. Lamaism was caught up in bloody struggles between the various monastic factions from the outset. There was a terrible “civil war” in which the country’s two main orders faced one another as opponents. Political murder has always been par for the course and even the Dalai Lamas have not been spared. Even in the brief history of the exiled Tibetans it is a constant occurrence. The concept of the enemy was deeply anchored in ancient Tibetan culture, and persists to this day. Thus the destruction of “enemies of the teaching” is one of the standard requirements of all tantric ritual texts. The sexual magic practices which lie at the center of this religion and which Thurman either conceals or interprets as an expression of cooperation and sexual equality are based upon a fundamental misogyny. The social misery of the masses in old Tibet was shocking and repulsive, the authority of the priestly state was absolute and extended over life and death. To present Tibet’s traditional society as a political example for modernity, in which the people had oriented themselves toward a “broad social ethic” and in which anybody could achieve “freedom and happiness” (Thurman 1998, p. 138) is farcical.

Thus one shudders at the thought when Thurman opens up the following perspective for the world to come: “In the sacred history of the transformation of the wild frontier [pre-Buddhist] land of Tibet [into a Buddhocracy], we find a blueprint for completing the taming of our own wild world” (Thurman 1998, p. 220)

Thurman introduces the Buddhist emperor Ashoka (regnant from 272 to 236 B.C.E.), who “saw the practical superiority of moral and enlightened policy” (Thurman 1998, p. 115), as a political example for the times ahead. He portrays this Indian emperor as a “prince of peace” who — although originally a terrible hero of the battlefield — following a deep inner conversion abjured all war, transformed hate and pugnacity into compassion and nonviolence, and conducted a “spiritual revolution” to the benefit of all suffering beings. In the chapter entitled “A kingly revolution” (Thurman 1988, pp.109ff.), the author suggests that the Ashoka kingdom’s form of government, oriented along monastic lines, could today once again function as a model for the establishment of a worldwide Buddhist state. Thurman says that “[t]he politics of enlightenment since Ashoka proposes a truth-conquest of the planet—a Dharma-conquest, meaning a cultural, educational, and intellectual conquest” (Thurman 1998, p. 282).

Thurman wisely remains silent about the fact that this Maurya dynasty ruler was responsible for numerous un-Buddhist acts. For instance, under his reign the death penalty for criminals was not abolished, among whom his own wife, Tisyaraksita, must have been counted, as he had her executed. In a Buddhist (!) description of his life, a Sanskrit work titled Ashokavandana, it states that he at one stage had 18,000 non-Buddhists, presumably Jainas, put to death, as one of them had insulted the “true teaching”, albeit in a relatively mild manner. In another instance he is alleged to have driven a Jaina and his entire family into their house which he then ordered to be burnt to the ground.

Nonetheless, Emperor Ashoka is a “cool revolutionary” for Thurman. His politics proclaimed “a social style of tolerance and admiration of nonviolence. They made the community a secure establishment that became unquestioned in its ubiquitous presence as school for gentleness, concentration, and liberation of critical reason; asylum for nonconformity; egalitarian democratic community, where decisions were made by consensual vote” (Thurman 1998, p. 117). To depict the absolutist emperor Ashoka as a guarantor and exemplar of an “egalitarian democratic community”, is a brilliant feat of arbitrary historical interpretation!

With equal emphasis Thurman presents the Indian/Buddhist Maha Siddhas (‘Grand Sorcerers’) as exemplary heroes of the ethos for whom there was no greater wish than to make others happy. However, as we have described in detail, these “ascetics who tamed the world” employed extremely dubious methods to this end, namely, they cultivated pure transgression in order to prove the vanity of all being. Their tantric, i.e., sexual magic, practices, in which they deliberately did evil (murder, rape, necrophagy) with the ostensible intention of creating something good, should, according to Thurman, be counted among the most significant acts of human civilization. Anyone who casts a glance over the “hagiographies” of these Maha Siddhas will be amazed at the barbaric consciousness possessed by these “heroes” of the tantric path. Only very rarely can socially ethical behavior be ascertained among these figures, who deliberately adopted asociality as a lifestyle.

But for Thurman these Maha Siddhas and their later Tibetan imitations are “radiant bodies of energy” upon whom the fate of humanity depends. “It is said that the hillsides and retreats of central Tibet were ablaze with the light generated by profound concentration, penetrating insights, and magnificent deeds of enthusiastic practitioners. The entire populace was moved by the energy released by individuals breaking through their age-old ignorance and prejudices and realizing enlightenment.” (Thurman 1998, pp. 227-228) When one compares the horrors of Tibetan history with the horrors in the tantric texts followed by the “enthusiastic practitioners”, then Thurman may indeed be correct. It is just that it was primarily dark energies which affected the Tibetan population and kept them in ignorance and servitude. Serfdom and slavery are attributes of old Tibetan society, just like an inhumane penal code and a pervasive oppression of women.

Padmasambhava, the supreme ambivalent founding figure of Tibetan Buddhism, is also celebrated by Thurman as a committed scholar of enlightenment. (Thurman 1998, 210). Nothing could be less typical of this sorcerer, who covered the Land of Snows with his excommunications and introduced the wrathful gods of pre-Buddhist Tibet in a horror army of aggressive protective spirits, not so that their terrible character could be transformed, but rather so that they could now protect with sword and fright the “true teaching of Buddha” from its enemies. Great scholars of the Gelugpa order have time and again pointed out the ambivalence of this iridescent “cultural founder” (Padmasambhava), among whose deeds are two brutal infanticides, and expressly distanced themselves from his barbaric lifestyle.

When the Indian scholar Atisha began his work in Tibet in the 11th century, he encountered a completely dissolute monastic caste in total chaos and where one could no longer speak of morals. At least this is what the historical records (the Blue Annals) report. Thurman suppresses this Lamaist moral collapse and simply maintains the opposite: “When Atisha arrived in Tibet, monastic practitioners were limiting themselves to strict moral and ritual observances” (Thurman 1998, p. 226). This is indeed a very euphemistic representation of the whoring and secularized monasteries against which Atisha took to the field with a new moral codex.

For Thurman, the Great Prayer Festival (Mönlam) institutionalized by Tsongkhapa and reactivated by the Fifth Dalai Lama, a raw Lamaist carnival in which monks were allowed absolutely everything and a truly horrible scapegoat ritual was performed, was a sacred event where “the power of compassion is manifest, the immediacy of grace is experienced” (Thurman 1998, p. 235). At another stage he says that, “[i]n Tibet, the Great Prayer Festival guaranteed the best of possibilities for everyone. People’s feelings of being in an apocalyptic time in a specially blessed and chosen land—in their own form of a “New Jerusalem”, a Kingdom of Heaven manifest on earth—had a powerful effect on the whole society” (Thurman 1998, pp. 238-239). When we compare this apotheosis of the said event with the already cited eyewitness report by Heinrich Harrer, we see the lack of restraint with which Thurman reveres the Tibet of old. Harrer, whose portrayal is confirmed by many other travel accounts, regarded the scenario completely differently: “As if emerging from hypnosis”, writes the mentor of the young Dalai Lama, “at this moment the tens of thousands spring from order in to chaos. The transition is so sudden, that one is speechless. Shouting, wild gesticulation .. they trample over one another, almost murder each other. The still-weeping prayers, ecstatically absorbed, become ravers. The monastic soldiers begin their duty! Huge fellows with stuffed shoulders and blackened faces — so that the deterrent effect becomes even stronger. Ruthlessly they lay into the crowd with their batons ... one takes the blows wailing, but even the beaten return again. As if they were possessed by demons” (Heinrich Harrer, 1984, p. 142). — Thurman’s “New Jerusalem”, possessed by demons on the roof of the world? —an interesting scenario for a horror film!

We find a further pinnacle of Thurman’s historical falsification in the portrait of the greatest Lamaist potentate, the Fifth Dalai Lama. Of all people, this “Priest-King” attuned to the accumulation of external power and pomp is built up by the author in to a hero of the “inner revolution”. He paints the picture of a prudent and farsighted fathers of his country (“a gentle genius, scholar, and reincarnate saint” — Thurman 1998, p. 248), who is compelled — against his will and his fundamentally Buddhist attitude — to conduct a horrific “civil war” (in which he lets great numbers of monks from other orders be massacred by the Mongol warriors summoned to the country). Thurman presents the conflict as a quarrel between various warlords in which the “peaceful” monks become embroiled.

Here again, the opposite was the case: the two chief Tibetan Buddhist orders of the time (Gelugpa and Kagyupa) were pulling the strings, even if they let worldly armies battle for them. Thurman misrepresents this monastic war as a battle between cliques of nobles and ultimately “the final showdown in Tibet between militarism and monasticism” (Thurman 1998, p. 249), whereby the latter as the party of peace is victorious thanks to the genius of the Fifth Dalai Lama and goes on to all but establish a “Buddha paradise” on earth.

All this is a pious/impudent invention of the American Tibetologist. The merciless warrior mentality of the Fifth Dalai Lama spread fear and alarm among his foes. His dark occult side, his fascination for the sexual magic of the Nyingmapa (which he himself practiced), his unrestrained rewriting of history and much more; these are all highly unpleasant facts, which are deliberately concealed by Thurman, since an historically accurate portrait of the “Great Fifth” could have embarrassing consequences, as the Fourteenth Dalai Lama constantly refers to this predecessor of his and has announced him to be his greatest example.

It would be wrong to deny the Fifth Dalai Lama any political or administrative skill; he was, just like his contemporary, Louis the Fourteenth, to whom he is often compared, an “ingenious” statesman. But this made him no prince of peace. His goal consisted of resolutely placing the fate of the country in the hands of the clergy with himself as the undisputed spiritual and secular leader. To this end (like the Fourteenth Dalai Lama today) he played the various orders off against one another. The Fifth Dalai Lama formulated the political foundations of a “Buddhocracy” which Robert Thurman would be glad to see as the model for a future worlds community, and which we wish to examine more closely in the next section.

A worldwide Buddhocracy

At the conference on Tibet in Bonn mentioned above (“Mythos Tibet”, 1996) Robert Thurman with stirring pathos prophesied the “fall of the West” and left no doubt that the future of our planet lies in a worldwide, as he stressed literally, “Buddhocracy”. Europe has renounced its sacred past, demystified its natural environment, established a secular realm, and closed off access to the sacred “represented by monasticism and its organized striving for perfection”. Materialism, industrialization and militarization have taken the place of the sacred (Thurman 1998, p. 246).

At the same time a reverse process has taken place in Tibet. Society has become increasingly sacralized and devoted itself to the creation of a “buddhaverse”. (In the wake of the Tibetologists’ criticisms in Bonn, Thurman appears to have opted for his own neologism “buddhaverse” in place of the somewhat offensive “Buddhocracy”; the meaning intended remains the same.) A re-enchantment of reality has taken place in Tibet, and the system is dedicated to the perfection of the individual. The warrior spirit has been dismantled. All these claims are untrue, and can be disproved by countless counterexamples. Nevertheless, Thurman presumes to declare them expressions of traditional Tibet’s “inner modernity”, which is ultimately superior to Europe’s “outer modernity”: “As Europe was pushing away the Pope, the Church, and the enchantment of everyday life, Tibet was turning over the reins of its country to a new kind of government, which cannot properly be called ‘theocratic’, since the Tibetans do not believe in an omnipotent God, but which can be called ‘Buddhocratic’” (Thurman 1998, p. 248). This form of government is supposed to guide our future. At the Tibet conference in Bonn, Thurman made this clearer: “Yes, not theocratic, because that brings [with it a] comparison to the Holy Roman Empire ... because it has the conception of an authoritarian God controlling the universe” (Thurman at the conference in Bonn). Thurman seems to think the concept of an “authoritarian Buddha” does not exist, although this is precisely what may be found at the basis of the Lamaist system.

For the author, the monasticization of Tibetan society was a lucky millennial event for humanity which reached its preliminary peak in the era in which the Gelugpa order was founded by Tsongkhapa (1357–1419) and the institution of the Dalai Lama was established. In Bonn Thurman praised this period as “the millennium of the fifteenth century of the planetary unique form of modern Tibetan society ... [which] led to the unfolding in the seventeenth century [of] what I call post-millennial, inwardly modern, mass-monastic, or even Buddhocratic [society]”. Tsongkhapa is presented as the founding father of this “modern Tibet”: he “was a spiritual prodigy. ... He perceived a cosmic shift from universe to buddhaverse” (Thurman 1998, pp. 232–233).

The Tibet of old was, according to Thurman, just such a buddhaverse, an earthly “Buddha paradise”, governed by nonviolence and wisdom, generosity, sensitivity, and tolerance. An exemplary enlightened consciousness was cultivated in the monastic Jewel Community. The monasteries provided the guarantee that politics was conducted along ethical lines: “The monastic core provides the cocoon for the free creativity of the lay Jewel Community” (Thurman 1998, p. 294).

This “monastic form of government”, pre-tested by Old Tibet, provides a vision for the future for Thurman: “I am very interested in this. I feel a very strong trend in this [direction]” (Thurman’s presentation in Bonn). The “monasticization” which was then (i.e., in the fifteenth century) spreading through Asia whilst the doors to the monasteries of Europe were closing, has once again become significant on a global political level. “And if you study Max Weber carefully... in fact what secularization and industrial progress brought had a lot to do with the slamming of the monastery doors. ... So, a monastic form of government is an unthinkable thing for Western society. We often say Tibet is frozen in the Middle Ages because Tibet is not secularized in the way the Western world is! It moved out of the balance between sacred and secular and went into a sacralization process and enchanted the universe. The concrete proof of that was that the monasteries provided the government” (Thurman in Bonn).

Here, Thurman is paraphrasing Weber’s thesis of the “disenchantment of the world” which accompanied the rise of capitalism. The “re-enchantment of the world” is a political program for him, which can only be carried out by Lamaist monks. Monasticism “is the shelter and training ground for the nonviolent ‘army’, the shock troops for the sustained social revolution the Buddha initiated ...” (Thurman 1998, p. 294, § 15). The monastic clergy would progressively assume control of political matters via a three-stage plan. In the final phase of this plan, “the society is able to enjoy the universe of enlightenment, and Jewel Community institutions [the monasteries] openly take responsibility for the society’s direction” (Thurman 1998, p. 296, § 24).

But this is no unreal utopia, since “Tibetan society is the only one in planetary history in which this third phase has been partially reached” (Thurman 1998, p. 296, § 25).In this sentence Thurman quite plainly proclaims a Buddhocracy along Lamaist lines to be the next model for the world community! Elsewhere, the Tibetologist is more precise: “The countercultural monastic movement no longer needs to lie low and is able to give the ruling powers advice, spiritual and social. Enlightened sages can begin to advise their royal disciples on how to conduct the daily affairs of society, such as what should be their policies and practices. Likewise, after a long period of such evolution, the entire movement can reach a cool fruition, when the countercultural enlightenment movement becomes mainstream and openly takes responsibility for the whole society, which eventually happened in Tibet” (Thurman 1998, p. 166, footnote).

According to Thurman, the Lamaist clergy assumes political power with — as we shall see — the incarnation of a super-being at its helm, an absolute monarch, who unites spiritual and worldly power within himself. The triumphant advance of the monastic system began in India in around 500 B.C.E. and spread throughout all of Asia in the intervening years. But this, Thurman says, is only a prelude: “The phenomenal success of monasticism, eventually Eurasia-wide, can be understood as the progressive truth-conquest of the world” (Thurman 1998, p. 105). Pie in the sky, or a event soon to come? Thurman’s statements on this are contradictory. In his book he talks of a “hope for the future”. But in interviews with the press, he has let it be known that he will experience the Buddhization of America in his own lifetime. In 1997, his friend, the Hollywood actor Richard Gere, was also convinced that the transformation of the world into a Buddhocracy would occur suddenly, like an atomic explosion, and that the “critical mass” would soon be reached (Herald Tribune, 20 March 1997, p. 6).

According to the author, the Lamaist power elite of the coming “Buddhocracy” is basically immortal because of the incarnation system. They already pulled the political strings in Tibet in the past, and will, in the author’s opinion, assume this role for the entire world in future: “Whatever the spiritual reality of these reincarnations, the social impact of this form of leadership was immense. It sealed the emerging spirituality of Tibetan society, in that death, which ordinarily interrupts progress in any society, could no longer block positive development. Just as Shakyamuni could be present to the practitioner through the initiation procedure and the sophisticated visualization techniques, so fully realized saints and sages were not withdrawn by death from their disciples, who depended on them to attain fulfillment (Thurman 1998, p. 231).

One can only be amazed — at the impudence with which Thurman praises the “Buddhocracy” of the Lamas as the highest form of “democracy”; at how he portrays Tibetan Buddhism, which is based upon a ritual dissolution of the individual, as the highest level of individual development; at how he depicts Tantrism, with its morbid sexual magic techniques for male monks to absorb feminine energies, as the only religion in which god and goddess are worshipped as balanced equals; at how he glorifies the cruel war gods and warrior monks of the Land of Snows as pacifists; at how he presents the medieval/monastic social form of Tibet as an expression of the modern and as offering the only model for a global world-society.

Tibet a land of enlightenment?

The Tibet of old, with its monastic culture was, according to Thurman, the cosmic energy body which irradiated our world in enlightened consciousness. “Hidden in the last thousand years of Tibet’s civilization”, the author says, “is a continuous process of inner revolution and cool evolution. In spiritual history, Tibet has been the secret dynamo that throughout this millennium has slowly turned the outer world toward enlightenment. Thus Tibetan civilization’s unique role on the inner plane of history assumes a far greater importance than material history would indicate” (Thurman 1998, p. 225). In Thurman’s version of history, it was not the Western bourgeoisie which fought for its freedoms and human rights in battle with the institutions of the Church; rather, all this was thought out in advance by holy men meditating among the Himalayan peaks: “The recent appearance of modern consciousness in the industrial world is not something radically new or unprecedented. Modern consciousness has been developed all over Asia in the Buddhist subcultures for thousands of years” (Thurman 1998, p. 255). —And it flowed into the consciousness of the modern, Western cultural elite as an Eastern energy source. That is, to speak clearly, the Tibetan monks meditating were one of the causes of the European Enlightenment. A bold thesis indeed, in which a Tibet controlled by a belief in ghosts, oracles, torture chambers, the oppression of women, and human super-beings becomes the cradle of modern rationalism.

The enlightening radiation began, says Thurman, with the Tibetan scholar Tsongkhapa’s edifice of teachings and the founding of the Gelugpa order: “This tremendous release of energy caused by thousands of minds becoming totally liberated in a short time was a planetary phenomenon, like a great spiritual pulsar emitting enlightenment in waves broadcast around the globe” (Thurman 1998, p. 233). Accordingly, Thurman considers all of the great Tibetan scholars of past centuries to be more significant and comprehensive than their European “peers”. They were “scientific heroes”, “”the quintessence of scientists in this nonmaterialistic civilization [i.e., Tibet]” (quoted by Lopez in Prisoners of Shangri-La, p. 81). As “psychonauts” they conquered inner space in contrast to the western “astronauts” (again quoted by Lopez, 1998, p. 81). But the “stars” of modern European philosophy like Hume and Kant, Nietzsche and Wittgenstein, Hegel and Heidegger, Thurman speculates, could also at some future time turn out to be line-holders for and emanations of the Bodhisattva of knowledge, Manjushri (Lopez, 1998, p. 264). Ex oriente lux — now also true for occidental science.

This incorporation of the Western cultural heroes is an underground current which flows through the entire neo-Buddhist scene. It is outwardly strictly denied, through the Dalai Lama’s demands for tolerance in broad publicity. In contrast, writings accumulate in the milieu, which celebrate Jesus Christ as an avatar of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara for example, the same super-being who has also been incarnated as the Dalai Lama. A recurrent image of modern myth building is the placement of the Tibetans on a par with the Nazarene.

Thurman as “high priest” of the Kalachakra Tantra

A worldwide Buddhocratic vision of Tibetan Buddhism is contained in what is known as the Kalachakra Tantra (the “Wheel of Time”). We have studied and commented upon this central Lamaist ritual in detail. The goal of the Kalachakra Tantra is the construction of a superhuman being, the ADI BUDDHA, whose control encompasses the entire universe, both spiritually and politically, “a mythical world-conqueror” (Thurman 1998, p. 292, § 5).

From a metapolitical point of view, Robert Thurman appears to have been appointed to implant the ideas of the Kalachakra Tantra in the West. We have already noted that the teacher the Dalai Lama assigned him to was Khen Losang Dondrub, Abbot of the Namgyal monastery which is especially commissioned to perform the Kalachakra ritual. In the USA he was in constant contact with the Kalmyk lama Geshe Wangyal (1901–1983). Lama Wangyal was Robert Thurman’s actual “line guru”, and this line leads via Wangyal directly to the old master Agvan Dorjiev (Lama Wangyal’s guru). Dorjiev the Buriat, Wangyal the Kalmyk, and Thurman the American thus form a chain of initiation. From a tantric point of view the spirit of the master lives on in the form of the pupil. One can thus assume that Thurman as Dorjiev’s successor represents an emanation of the extremely aggressive protective divinity Vajrabhairava who is supposed to have become incarnate in the Buriat. At any rate the American must be drawn into the context of the global Shambhala utopia, which was the principal concern of Dorjiev’s metapolitics.

What Thurman understands by this can be most clearly illustrated by a vision which was bestowed upon him in a dream in September 1979, before he saw the Dalai Lama again for the first time in eight years: “The night before he landed in New York, I dreamed he was manifesting the pure land mandala palace of the Kalachakra Buddha right on top of the Waldorf Astoria building. The entire collection of dignitaries of the city, mayors and senators, corporate presidents and kings, sheikhs and sultans ,celebrities and stars—all of them were swept up into the dance of 722 deities of the three buildings of the diamond palace like pinstriped bees swarming on a giant honeycomb. The amazing thing about the Dalai Lama’s flood of power and beauty was that it appeared totally effortless. I could feel the space of His Holiness’s heart, whence all this arose. It was relaxed, cool, an amazing well of infinity” (Thurman 1998, p. 18).

The magic projection of the Tibetan “god-king” as ADI BUDDHA and world ruler cannot be illustrated more vividly. He reigns as some kind of queen bee in the middle of New York, and lets the world’s greatest, whom he has bewitched with sweet honey, dance to his tune. It is typical that there is no mention of grass roots democracy here, and that it is just the political, business, and show business Establishment which performs the sweet dance of the bees. Anyone who is aware how much significance is granted to such dreams in the world of Tibetan initiation will without further ado recognize a metapolitical program in Thurman’s vision. [1]

In 1992, as Director of Tibet House in New York City which he co-founded with Richard Gere, he sponsored “the Kalachakra Initiation at New York’s Madison Square Garden.” (Farrer-Halls 1998, p. 92) The Tibet Center houses a three dimensional Kalachakra Mandala and the only life sized statue of the Kalachakra deity outside of Tibet. Following the first World Trade Center bombing in 1993, “The Samaya Foundation, the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, and the Port Authority jointly sponsored the Wheel of Time (Kalachakra) Sand Mandala, or Circle of Peace, in the lobby of Tower 1.” (Darton 1999, p. 219) For over thirty days, many of the World Trade Center workers and visitors were invited by the Namgyal Monks to participate in the construction of the mandala. It is said that, “ Its shape symbolized nature’s unending cycle of creation and destruction and in the countless grains of its material, it celebrated life’s energy taking ephemeral form, then returning to its source. At the end of the mandala’s month long lifespan, the monks swept up the sand and “offered it to the Hudson River.” This ritual, they believed, purified the environment. (Darton 1999, p. 219)Report of a former participant of the Kalachakra Ceremony in New York: “Get a call from one of my Kalachakra sisters I haven't heard from since the Indiana Kalachakra in '99. […] The topic shifted to the Kalachakra mandala that was made at One World Trade Center. I was at the dissolution ceremony there, may be around '96. The monks gathered up all the sand from the mandala at 1WTC, put it in a vase, then carried it across the bridge into World Financial Center through the Winter Garden, then dumped the sand ceremoniously into the Hudson River for the sake of World Peace. The surface of the river glittered with the afternoon sun, and I cried. 5 years later, the whole building is gone, just like the sand mandala.” See: http://home.earthlink.net/~kamitera/news.html

Thurman’s devoted commitment as Lamaist initiand, his absolute loyalty to the Dalai Lama, his consistent vision of an earthly “Buddha paradise”, his uncompromising affirmation of a Buddhocratic state, his involvement with the world of the Tibetan gods which reaches even into his own dreams, his systematic training by the highest Tibetan lamas over many years—all these certify Thurman to be a “Shambhala warrior”, a Buddhist hero, who according to legend prepares for the establishment of the kingdom of Shambhala over our globe. This is the goal of the Kalachakra ritual (the “Wheel of Time” ritual) performed all over the world by the Dalai Lama. Thurman has, he reports, seen the Dalai Lama in a vision as the supreme time god above the Waldorf Astoria. But even here he conceals that the Shambhala myth is not peaceful, and can only be realized after a world war in which all nonbelievers (non-Buddhists) are destroyed.

Perhaps such a perspective frightens some Western intellectuals? No worries, Thurman reassumes them, “who is afraid of the Dalai Lama? Who is afraid of Avalokiteshvara? No Tibetans are afraid” (Thurman in Bonn). How could one be afraid of the supreme enlightened being currently on earth? He, in whom all three levels are compressed, “that of the selfless monk, the king, and the great adept” (Thurman), who is (as great adept) preparing the creation of “a buddhaversal human society” (Thurman 1998, p. 39), even if he (as king and statesman) is still concentrating chiefly on the concerns of Tibet. Then, “Tibet’s unique focus on enlightenment civilization makes the nation crucial to the world’s development of spiritual and social balance” (Thurman 1998, p. 39).

Thurman is convinced that the Dalai Lama represents a projection of the ADI BUDDHA, who can liberate the world from its valley of sorrows. He describes very precisely the micro- and macrocosmic dimensions of such a redemptive being in the form of the Fifth Dalai Lama. If humanity were to recognize the divine presence behind the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, it could calmly place its political matters in his hands, just as the Tibetan populace did in the time of the “Great Fifth”: “Small wonder”, Thurman tells his readers. “Suppose the people of a catholic country were to share a perception of a particular spiritual figure as not simply a representative of God, as in the Pope being the vicar of Christ, but as an actual incarnation of the Savior—or, say an incarnation of the Archangel Gabriel. In such a situation it would not be strange for the nation to reach a point where the divine would actually take responsibility for the government. In Tibet, this moment was the culmination of centuries of grass-roots millennial consciousness, the political ratification of the millennial direction that had been intensifying since the Great Prayer Festival tradition had begun in 1409. The sense of the presence of an enlightened being was widespread enough for the people to join together after the last conflict and entrust to him their land and their fate” (Thurman 1998, pp. 250–251).

There is no need to read between the lines, simply paying close attention to the text of his book is enough to be able to recognize that, for Thurman, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama represents the quintessence of political wisdom and decisive power for the coming millennium. The author draws attention to the five principles of his planetary political program: “nonviolence, individualism, education, and altruistic correctedness. The fifth [principle], global democratism, is exemplified in His Holiness the Great Fourteenth Dalai Lama himself” (Thurman 1998, p. 279). The Tibetan “god-king” as the incarnation of universal democracy—a true piece of bravura in Thurman’s “political theology”. No wonder the “god-king” applauds him so roundly in his foreword: “I commend him for his careful study and clear explanations, and I recommend his insights for your own reflections” (Thurman 1998, p. xiv).

According to Thurman, the USA is the first western country in which the lamas’ Buddhocratic vision will prevail: “Most of the teachers from the various enlightenment movements seem to agree on one thing: If there is to be a renaissance of enlightenment sciences in our times, it will have to begin in America. America is the land of extreme dichotomies: the great materialism and the greatest disillusionment with materialism; great self-indulgence and great self-transcendence” (Thurman 1998, p. 280). The Dalai Lama (“the fifth [principle of] global democratism”) as the next American president? —But if he dies?—No worries, thanks to the system of incarnation he may remain among us as priest and king for ever.

Thurman’s methods, adapting himself to the point of self-deception to the consciousness and the customs of his environment (in this case the western democratic environment), but without losing sight of the actual grand metapolitical goal, has a long tradition in Tibet. Padmasambhava, for instance, Buddhized the Land of Snows by integrating with aplomb the various tribal cultures which he encountered on his missionary travels into his tantric system, together with their particular ideas and cultic practices. In doing so he was so skillful that the pre-Buddhist inhabitants of Tibet believed Buddhism to be no more than the realization of their own traditional expectations of salvation. The Fourteenth Dalai Lama is masterfully repeating this heuristic principle from his eighth-century incarnation on the world stage. In the meantime he knows all the variations and rules of the game of Western civilization and has managed to generate a public image as a great reformer and democrat who brilliantly combines modern political fundamentals with old Eastern teachings of wisdom. There are countless sermons from him in which he strongly advises his audience to stay true to their own religious tradition, since in the end they all come to the same thing. Such superior invitations have as we shall see a double-bind effect. People are so enthused by the ostensible tolerance of Tibetan Buddhism and its supreme representative that they become converts to the Dharma and ensnared in the tantric web.[/size][/b]

-- The Shadow of the Dalai Lama: Sexuality, Magic and Politics in Tibetan Buddhism, by Victor and Victoria Trimondi