Part 2 of 2

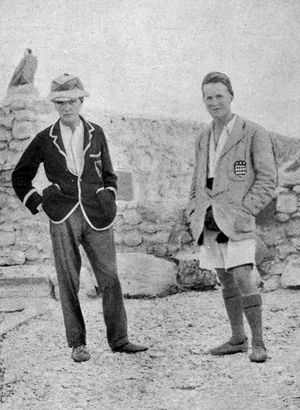

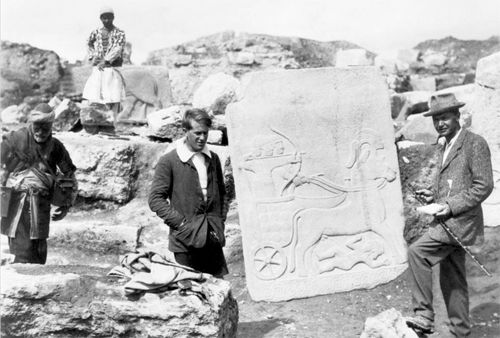

SexualityLawrence's biographers have discussed his sexuality at considerable length, and this discussion has spilled into the popular press.[169] There is no reliable evidence for consensual sexual intimacy between Lawrence and any person. His friends have expressed the opinion that he was asexual,[170][171] and Lawrence himself specifically denied any personal experience of sex in multiple private letters.[172] There were suggestions that Lawrence had been intimate with Dahoum, who worked with him at a pre-war archaeological dig in Carchemish,[173] and fellow serviceman R. A. M. Guy,[174] but his biographers and contemporaries found them unconvincing.[173][174][175]

The dedication to his book Seven Pillars is a poem titled "To S.A." which opens:

I loved you, so I drew these tides of men into my hands

and wrote my will across the sky in stars

To earn you Freedom, the seven-pillared worthy house,

that your eyes might be shining for me

When we came.

Lawrence was never specific about the identity of "S.A." Many theories argue in favour of individual men or women, and the Arab nation as a whole. The most popular theory is that S.A. represents (at least in part) his companion Selim Ahmed, "Dahoum", who apparently died of typhus before 1918.[176][177][178]

Lawrence lived in a period of strong official opposition to homosexuality, but his writing on the subject was tolerant. He wrote to Charlotte Shaw, "I've seen lots of man-and-man loves: very lovely and fortunate some of them were."[179] He refers to "the openness and honesty of perfect love" on one occasion in Seven Pillars, when discussing relationships between young male fighters in the war.[180] He wrote in Chapter 1 of Seven Pillars:

In horror of such sordid commerce [diseased female prostitutes] our youths began indifferently to slake one another's few needs in their own clean bodies—a cold convenience that, by comparison, seemed sexless and even pure. Later, some began to justify this sterile process, and swore that friends quivering together in the yielding sand with intimate hot limbs in supreme embrace, found there hidden in the darkness a sensual co-efficient of the mental passion which was welding our souls and spirits in one flaming effort [to secure Arab independence]. Several, thirsting to punish appetites they could not wholly prevent, took a savage pride in degrading the body, and offered themselves fiercely in any habit which promised physical pain or filth.[181]

There is considerable evidence that Lawrence was a masochist. He wrote in his description of the Dera'a beating that "a delicious warmth, probably sexual, was swelling through me," and he also included a detailed description of the guards' whip in a style typical of masochists' writing.[182] In later life, Lawrence arranged to pay a military colleague to administer beatings to him,[183] and to be subjected to severe formal tests of fitness and stamina.[184] John Bruce first wrote on this topic, including some other statements that were not credible, but Lawrence's biographers regard the beatings as established fact.[185] French novelist André Malraux admired Lawrence but wrote that he had a "taste for self-humiliation, now by discipline and now by veneration; a horror of respectability; a disgust for possessions".[186]

Psychologist John E. Mack sees a possible connection between Lawrence's masochism and the childhood beatings that he had received from his mother[187] for routine misbehaviours.[188] His brother Arnold thought that the beatings had been given for the purpose of breaking his brother's will.[188] Angus Calder suggested in 1997 that Lawrence's apparent masochism and self-loathing might have stemmed from a sense of guilt over losing his brothers Frank and Will on the Western Front, along with many other school friends, while he survived.[189]

The Aldington ControversyIn 1955 Richard Aldington published Lawrence of Arabia: A Biographical Enquiry, a sustained attack on Lawrence's character, writing, accomplishments, and truthfulness. Specificaly, Aldington alleges that Lawrence lied and exaggerated continuously, promoted a misguided policy in the Middle East, that his strategy of containing but not capturing Medina was incorrect, and that Seven Pillars of Wisdom was a bad book with few redeeming features. He also revealed Lawrence's illegitimacy and strongly suggested that he was homosexual. For example: "Seven Pillars of Wisdom is rather a work of quasi-fiction than history."[190], and "It was seldom that he reported any fact or episode involving himself without embellishing them and indeed in some cases entirely inventing them."[191]

It is significant that Aldington was a colonialist, arguing that the French colonial administration of Syria (strongly resisted by Lawrence) had benefited that country[192] and that Arabia's peoples were "far enough advanced for some government though not for complete self-government."[193] He was also a Francophile, railing against Lawrence's "Francophobia, a hatred and an envy so irrational, so irresponsible and so unscrupulous that it is fair to say his attitude towards Syria was determined more by hatred of France than by devotion to the 'Arabs' - a convenient propaganda word which grouped many disharmonious and even mutually hostile tribes and peoples."[194]

Prior to the publication of Aldington's book, its contents became known in London's literary community. A group Aldington and some subsequent authors referred to as "The Lawrence Bureau"[195], led by B. H. Liddell Hart[196] tried energetically, starting in 1954, to have the book suppressed.[197] That effort having failed, Liddell Hart prepared and distributed hundreds of copies of Aldington's 'Lawrence': His Charges--and Treatment of the Evidence, a 7-page single-spaced document.[198] This worked: Aldington's book received many extremely negative and even abusive reviews, with strong evidence that some reviewers had read Liddell's rebuttal but not Aldington's book.[199]

Aldington wrote that Lawrence embellished many stories and invented others, and in particular that his claims involving numbers were usually inflated - for example claims of having read 50,000 books in the Oxford Union library, of having blown up 79 bridges, of having had a price of £50,000 on his head, and of having suffered 60 or more injuries. Many of Aldington's specific claims against Lawrence have been accepted by subsequent biographers. In Richard Aldington and Lawrence of Arabia: A Cautionary Tale, Fred D. Crawford writes "Much that shocked in 1955 is now standard knowledge--that TEL was illegitimate, that this profoundly troubled him, that he frequently resented his mother's dominance, that such reminiscences as T.E. Lawrence by His Friends are not reliable, that TEL's leg-pulling and other adolescent traits could be offensive, that TEL took liberties with the truth in his official reports and Seven Pillars, that the significance of his exploits during the Arab Revolt was more political than military, that he contributed to his own myth, that when he vetted the books by Graves and Liddell he let remain much that he knew was untrue, and that his feelings about publicity were ambiguous."[200]

This has not prevented most post-Aldington biographers (including Fred D. Crawford, who studied the Aldington claims intensely) from expressing strong admiration for Lawrence’s military, political, and writing achievements.

Awards and commemorations Eric Kennington's bust of Lawrence at St Paul's Cathedral

Eric Kennington's bust of Lawrence at St Paul's Cathedral The head of Lawrence's effigy in St Martin's Church, Wareham

The head of Lawrence's effigy in St Martin's Church, WarehamLawrence was appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath on 7 August 1917,[1] appointed a Companion of the Distinguished Service Order on 10 May 1918,[2] awarded the Knight of the Legion of Honour (France) on 30 May 1916[3] and awarded the Croix de guerre (France) on 16 April 1918.[4]

A bronze bust of Lawrence by Eric Kennington was placed in the crypt of St Paul's Cathedral, London, on 29 January 1936, alongside the tombs of Britain's greatest military leaders.[201] A recumbent stone effigy by Kennington was installed in St Martin's Church, Wareham, Dorset, in 1939.[202][203]

An English Heritage blue plaque marks Lawrence's childhood home at 2 Polstead Road, Oxford, and another appears on his London home at 14 Barton Street, Westminster.[204][205] Lawrence appears on the album cover of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band by The Beatles. In 2002, Lawrence was named 53rd in the BBC's list of the 100 Greatest Britons following a UK-wide vote.[206]

In popular culture

Film· Alexander Korda bought the film rights to The Seven Pillars in the 1930s. The production was in development, with various actors cast as the lead, such as Leslie Howard.[207]

· Peter O'Toole was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actor for his portrayal of Lawrence in the 1962 film Lawrence of Arabia.[208]

· Lawrence portrayed by Robert Pattinson in the 2014 biographical drama about Gertrude Bell, Queen of the Desert.[209]

· Peter O'Toole's portrayal of Lawrence inspired behavioural affectations in the synthetic model called David, portrayed by Michael Fassbender in the 2012 film Prometheus, and in the 2017 sequel Alien: Covenant, part of the Alien franchise.[210]

Literature· T.E. Lawrence is a 1980 manga by Tomoko Kousaka, which retells the story of Lawrence and his participation in the Arab Revolt.[211]

· The T.E. Lawrence Poems was published by Canadian poet Gwendolyn MacEwen in 1982.[212]. The poems rely heavily, and quote directly from, primary material including Seven Pillars and the collected letters.

Television· He was portrayed by Judson Scott in the 1982 TV series Voyagers![213]

· Ralph Fiennes portrayed Lawrence in the 1992 British made-for-TV movie A Dangerous Man: Lawrence After Arabia.[214]

· Joseph A. Bennett and Douglas Henshall portrayed him in the 1992 TV series The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles.[215]

· He was also portrayed in a Syrian series, directed by Thaer Mousa, called Lawrence Al Arab. The series consisted of 37 episodes, each between 45 minutes and one hour in length.[216]

Theatre· Lawrence was the subject of Terence Rattigan's controversial play Ross, which explored Lawrence's alleged homosexuality. Ross ran in London in 1960–61, starring Alec Guinness, who was an admirer of Lawrence, and Gerald Harper as his blackmailer, Dickinson. The play had originally been written as a screenplay, but the planned film was never made. In January 1986 at the Theatre Royal, Plymouth, on the opening night of the revival of Ross, Marc Sinden, who was playing Dickinson (the man who recognised and blackmailed Lawrence, played by Simon Ward), was introduced to the man on whom the character of Dickinson was based. Sinden asked him why he had blackmailed Ross, and he replied, "Oh, for the money. I was financially embarrassed at the time and needed to get up to London to see a girlfriend. It was never meant to be a big thing, but a good friend of mine was very close to Terence Rattigan and years later, the silly devil told him the story."[217]

· Alan Bennett's Forty Years On (1968) includes a satire on Lawrence; known as "Tee Hee Lawrence" because of his high-pitched, girlish giggle. "Clad in the magnificent white silk robes of an Arab prince ... he hoped to pass unnoticed through London. Alas he was mistaken."[218]

· The character of Private Napoleon Meek in George Bernard Shaw's 1931 play Too True to Be Good was inspired by Lawrence. Meek is depicted as thoroughly conversant with the language and lifestyle of the native tribes. He repeatedly enlists with the army, quitting whenever offered a promotion. Lawrence attended a performance of the play's original Worcestershire run, and reportedly signed autographs for patrons attending the show.[219]

· Lawrence's first year back at Oxford after the War to write was portrayed by Tom Rooney in a play, The Oxford Roof Climbers Rebellion, written by Canadian playwright Stephen Massicotte (premiered Toronto 2006). The play explores Lawrence's reactions to war, and his friendship with Robert Graves. Urban Stages presented the American premiere in New York City in October 2007; Lawrence was portrayed by actor Dylan Chalfy.[220]

· Lawrence's final years are portrayed in a one-man show by Raymond Sargent, The Warrior and the Poet.[221]

· His 1922 retreat from public life forms the subject of Howard Brenton's play Lawrence After Arabia, commissioned for a 2016 premiere at the Hampstead Theatre to mark the centenary of the outbreak of the Arab Revolt.[222]

· A highly fictionalised version of Lawrence featured in the 2016 Swedish-language comedic play Lawrence i Mumiedalen.[223]

See also· Hashemite

· Kingdom of Iraq

· Lawrence of Arabia: The Authorised Biography of T. E. Lawrence

· The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones (1992–1993)

· Suleiman Mousa

References

Citations1. "No. 30222". The London Gazette (Supplement). 7 August 1917. p. 8103.

2. "No. 30681". The London Gazette (Supplement). 10 May 1918. p. 5694.

3. "No. 29600". The London Gazette. 30 May 1916. p. 5321.

4. "No. 30638". The London Gazette (Supplement). 16 April 1918. p. 4716.

5. Benson-Gyles, Dick (2016). The Boy in the Mask: The Hidden World of Lawrence of Arabia. The Lilliput Press.

6. Aldington, 1955, p. 25.

7. Alan Axelrod (2009). Little-Known Wars of Great and Lasting Impact. Fair Winds, 2009. p. 237. ISBN 9781616734619. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

8. David Barnes (2005). The Companion Guide to Wales. Companion Guides, 2005. p. 280. ISBN 9781900639439. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

9. "Snowdon Lodge". Retrieved 17 April 2017.

10. Mack, 1976, p. 5.

11. Aldington, 1955, p. 19.

12. "T. E. Lawrence Studies". Telstudies.org. 13 May 1935. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

13. Wilson, 1989, Appendix 1.

14. Mack, 1976, p. 9.

15. Mack, 1976, p. 6.

16. Wilson, 1989, p. 22.

17. Wilson, 1989, p. 24.

18. Wilson, Jeremy (2 December 2011). "T. E. Lawrence: from dream to legend". T.E. Lawrence Studies. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

19. Wilson 1989, p. 24.

20. Mack, 1976, p. 22.

21. "Brief history of the City of Oxford High School for Boys, George Street". University of Oxford Faculty of History. Archived from the original on 18 April 2012. Retrieved 25 June 2008.

22. Aldington, 1955, p. 53.

23. "T. E. Lawrence Studies". Telawrence.info. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

24. Wilson, 1989, p. 33, in note 34 Wilson discusses a painting in Lawrence's possession at the time of his death which appears to show him as a boy in RGA uniform.

25. Beeson, C.F.C.; Simcock, A.V. (1989) [1962]. Clockmaking in Oxfordshire 1400–1850 (3rd ed.). Oxford: Museum of the History of Science. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-903364-06-5.

26. Larès, Maurice "T.E. Lawrence and France: Friends or Foes?" pages 220–242 from The T.E. Lawrence Puzzle edited by Stephen Tabachnick, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984 page 222.

27. Wilson, 1989, p. 42.

28. Wilson, 1989, pp. 45–51.

29. Penaud, 2007.

30. Wilson, 1989 pp. 57–61.

31. Wilson, 1989, p. 67.

32. Allen, Malcolm Dennis (1 November 2010). The Medievalism of Lawrence of Arabia. Penn State Press, 1991. p. 29. ISBN 978-0271040608. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

33. Allen, M.D. "Lawrence's Medievalism" pages 53–70 from The T.E. Lawrence Puzzle edited by Stephen Tabachnick, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984 page 53.

34. Wilson, 1989, p. 70.

35. Wilson, p. 73.

36. Wilson, 1989, pp. 76–77.

37. Wilson, 1989, pp. 76–134.

38. "T. E. Lawrence letters, 1927". Archived from the original on 11 February 2012.

39. Wilson, 1989, p. 88.

40. Wilson, 1989, pp. 99–100.

41. Wilson, 1989, p. 136. Lawrence wrote to his parents "We are obviously only meant as red herrings to give an archaeological colour to a political job."

42. "Internet Archive Wayback Machine". 18 October 2006. Archived from the original on 18 October 2006. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

43. "Adventure in the desert on the trail of Lawrence of Arabia". The Telegraph. 24 October 2016. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

44. Korda, 2010, p. 251.

45. Wilson, 1989, p. 166.

46. Wilson, 1989, pp. 152, 154.

47. Wilson, 1989, p. 158.

48. Wilson, 1989, p. 199.

49. Wilson, 1989, p. 195.

50. Wilson, 1989, pp. 169–170.

51. Wilson, 1989, p. 161.

52. Wilson, 1989, p. 189.

53. Wilson, 1989, p. 188.

54. Wilson, 1989, p. 181.

55. Wilson, 1989, p. 186.

56. Wilson, 1989, pp. 211–212.

57. McMahon, Henry; bin Ali, Hussein (1939), Cmd.5957; Correspondence between Sir Henry McMahon, G.C.M.G., His Majesty's High Commissioner at. Cairo and the Sherif Hussein of Mecca, July, 1915-March, 1916 (with map) (PDF), HMG

58. Wilson, 1989, pp. 256–276.

59. Wilson, 1989, p. 313. In note 24, Wilson argues that Lawrence must have known about Sykes-Picot prior to his relationship with Faisal, contrary to a later statement.

60. Wilson, 1989, p. 300.

61. Wilson, 1989, p. 302.

62. Wilson, pp. 307–311.

63. Wilson, 1989, p. 312.

64. Wilson, p. 321.

65. Wilson, 1989, p. 323.

66. Wilson, 1989, p. 347. Also see note 43, where the origin of the repositioning idea is examined closely.

67. Wilson, 1989, p. 358.

68. Wilson, 1989, p. 348

69. Wilson, 1989, p. 388.

70. Alleyne, Richard (30 July 2010). "Garland of Arabia: the forgotten story of TE Lawrence's brother-in-arms". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

71. Wilson, 1989, p. 412

72. Wilson, 1989, p. 416.

73. Wilson, 1989, p. 446.

74. Wilson, 1989, p. 448.

75. Wilson, 1989, pp. 455–457.

76. Mack, 1976, pp. 158, 161.

77. Lawrence, 7 Pillars (1922), pp. 537–546.

78. Wilson, 1989, p. 495.

79. Wilson, 1989, p. 498.

80. Wilson, 1989, p. 546.

81. Wilson, 1989, pp. 556–557.

82. Wilson, 1989, pp. 424–425.

83. Wilson, 1989, p. 491.

84. Wilson, 1918, p. 479.

85. Morsey, Konrad "T.E. Lawrence: Strategist" pages 185–203 from The T.E. Lawrence Puzzle edited by Stephen Tabachnick, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984 page 194.

86. Wilson, 1989, p. 353.

87. Murphy, David (2008). "The Arab Revolt 1916–1918", London: Osprey, 2008 page 36.

88. Wilson, 1989, p. 329 describes a very early argument for letting the Ottomans stay in Medina in a November 1916 letter from Clayton.

89. Wilson, 1989, pp. 383–384 describes Lawrence's arrival at this conclusion. However, Aldington 1955 disagrees strongly with the value of the strategy, p. 178.

90. Wilson, 1989, pp. 361–362 argues that Lawrence knew the details and briefed Faisal in February 1917.

91. Wilson, 1989, p. 444. shows Lawrence definitely knew of Sykes-Picot in September 1917.

92. Wilson, 1989, p. 309.

93. Wilson, 1989, pp. 390–391.

94. "The bombardment of Akaba." The Naval Review. Volume IV. 1916. pp. 101–103

95. "Egyptian Expeditionary Force". Operations in the Gulf of Akaba, Red Sea HMS Raven II. July—August 1916. National Archives, Kew London. File: AIR 1 /2284/ 209/75/8.

96. "Naval Operation in the Red Sea 1916—1917". The Naval Review, Volume XIII, no.4 (1925). pp. 648–666.

97. Graves, 1934, p. 161. "Akaba was so strongly protected by the hills, elaborately fortified for miles back, that if a landing were attempted from the sea a small Turkish force could hold up a whole Allied division in the defiles."

98. Wilson, 1989, p. 400.

99. Wilson, 1989, p. 397.

100. Wilson, 1989, p. 406.

101. "Strategist of the Desert Dies in Military Hospital". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 August 2012

102. Letter to W.F. Stirling, Deputy Chief Political Officer, Cairo, 28 June 1919, in Brown, 1988.

103. Mack, 1976.

104. Day, Elizabeth (14 May 2006). "Lawrence of Arabia 'made up' sex attack by Turk troops". The Daily Telegraph.

105. Barr, James. Setting the Desert on Fire: T. E. Lawrence and Britain's Secret War in Arabia 1916–1918.

106. Wilson, 1989, note 49 to Chapter 21.

107. Lawrence, T. E. (1935). Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Jonathan Cape, p. 447

108. Barker, A (1998). "The Allies Enter Damascus". History Today. 48.

109. Eliezer Tauber. The Formation of Modern Syria and Iraq. Frank Cass and Co. Ltd. Portland, Oregon. 1995.

110. Rory Stewart (presenter) (23 January 2010). The Legacy of Lawrence of Arabia. 2. BBC.

111. Asher, 1998, p. 343.

112. "Newsletter: Friends of the Protestant Cemetery" (PDF). protestantcemetery.it. Rome. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2012.

113. RID Marzo 2012, Storia dell'Handley Page type 0

114. "UK – Lawrence's Mid-East map on show". 11 October 2005.

115. Hall, Rex (1975). The Desert Hath Pearls. Melbourne: Hawthorn Press. pp. 120–121.

116. Murphy, David The Arab Revolt 1916–18, London: Osprey, 2008, page 86

117. Aldington, 1955, p. 283

118. Aldington, 1955, p. 284.

119. Aldington, 1955, p. 108.

120. Aldington, 1955, pp. 293, 295.

121. Korda, 2010, pp. 513, 515.

122. Klieman, Aaron "Lawrence as a Bureaucrat" pages 243–268 from The T.E. Lawrence Puzzle edited by Stephen Tabachnick, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984 page 253.

123. Korda, 2010, p. 519.

124. Korda, 2010, p. 505.

125. Larès, Maurice "T.E. Lawrence and France: Friends or Foes?" pages 220–242 from The T.E. Lawrence Puzzle edited by Stephen Tabachnick, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984 page 224 & 236–237.

126. Larès, Maurice "T.E. Lawrence and France: Friends or Foes?" pages 220–242 from The T.E. Lawrence Puzzle edited by Stephen Tabachnick, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984 page 236.

127. Biography of Johns, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

128. Orlans, 2002, p. 55.

129. Korda, 2020, p. 577.

130. "T. E. Lawrence". London Borough of Hillingdon. 23 October 2007. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

131. Sydney Smith, Clare (1940). The Golden Reign – The story of my friendship with Lawrence of Arabia. London: Cassell & Company. p. 16.

132. Korda, 2010, pp. 620, 631.

133. "Report Lawrence now a Muslim Saint, Spying on the Bolshevist Agents in India". The New York Times. 27 September 1928. p. 1.

134. "Pole Hill". T.E. Lawrence Society. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

135. "On this day in 1935: The death of Lawrence of Arabia". The Telegraph. Retrieved 19 January2020.

136. Crompton, Teresa (2020). Adventuress, the Life and Loves of Lucy, Lady Houston. The History Press. p. 193.

137. Beauforte-Greenwood, W. E. G. "Notes on the introduction to the RAF of high-speed craft". T. E. Lawrence Studies. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

138. Korda, 2010, p. 642.

139. Erwin Tragatsch (ed.) (1979). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Motorcycles. New Burlington Books. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-906286-07-4.

140. "Lawrence of Arabia". Retrieved 21 October 2013.

141. Brough Superior Club> Archived 3 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 5 May 2008]

142. "Lawrence of Arabia? We're more into the Taliban now". London Evening Standard. 25 February 2013. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

143. Walter F. Oakeshott (1963). "The Finding of the Manuscript," Essays on Malory, J. A. W. Bennett, ed. (Oxford: Clarendon, 93: 1—6).

144. "T. E. Lawrence, To Arabia and back". BBC. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

145. "Dorset". T.E. Lawrence Society. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

146. "Lawrence of Arabia, Sir Hugh Cairns, and the Origin of Motor... : Neurosurgery". LWW.[permanent dead link]

147. Kerrigan, Michael (1998). Who Lies Where – A guide to famous graves. London: Fourth Estate Limited. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-85702-258-2.

148. Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2. McFarland & Company (2016) ISBN 0786479922

149. Moffat, W. "A Great Unrecorded History: A New Life of E. M. Forster", p.240

150. T. E. Lawrence (2000). Jeremy and Nicole Wilson (ed.). Correspondence with Bernard and Charlotte Shaw, 1922–1926. 1. Castle Hill Press. Foreword by Jeremy Wilson.

151. Korda, 2010, p. 137.

152. Orlans, 2002, p. 132.

153. "Found: Lawrence of Arabia's lost text". The Independent. 13 April 1997. Retrieved 18 January2020.

154. Asher, 1998, p. 259.

155. Graves, 1928, ch. 30.

156. Mack, 1976, p. 323.

157. Grand Strategies; Literature, Statecraft, and World Order, Yale University Press, 2010, p. 8.

158. "T. E. Lawrence to D. G. Hogarth". T.E. Lawrence Society. 7 April 1927. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

159. Norman, Andrew (2014). T.E.Lawrence: Tormented Hero. Fonthill Media. ISBN 978-1781550199.

160. Doubleday, Doran & Co, New York, 1936; rprnt Penguin, Harmondsworth,1984 ISBN 0-14-004505-8

161. Lawrence, T.E. (1955). The Mint, by 352087 A/c Ross A Day-book of the R.A.F. Depot between August and December 1922. Jonathan Cape.

162. Orlans, 2002, p. 134.

163. "Seven Pillars of Wisdom Fund". Research.britishmuseum.org. British Museum. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

164. Charity Commission. Seven Pillars Of Wisdom Trust, registered charity no. 208669.

165. "British copyright law and T. E. Lawrence's writings". T.E. Lawrence Society. Retrieved 19 January2020.

166. "Castle Hill Press". www.castlehillpress.com.

167. Lawrence, T. E. "Guerilla Warfare". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

168. "EOS". www3.lib.uchicago.edu.

169. The Sunday Times pieces appeared on 9, 16, 23, and 30 June 1968, and were based mostly on the narrative of John Bruce.

170. E.H.R. Altounyan in Lawrence, A. W., 1937.

171. Knightley and Simpson, 1970, p. 29

172. Brown, 1988, letters to E. M. Forster (21 Dec 1927), Robert Graves (6 Nov 1928), F. L. Lucas (26 March 1929).

173. C. Leonard Woolley in A. W. Lawrence, 1937, p. 89

174. Wilson, 1989, chapter 32.

175. Wilson, 1989, chapter 27.

176. Yagitani, Ryoko. "An 'S.A.' Mystery".

177. Benson-Gyles, Dick (2016). The Boy in the Mask: The Hidden World of Lawrence of Arabia. The Lilliput Press. Benson-Gyles argues for Farida Al-Akle, a Syrian woman from Byblos (now in Lebanon) who taught Arabic to Lawrence prior to his architectural career.

178. Korda, 2010, p. p. 498.

179. Letter to Charlotte Shaw in Mack, 1976, p. 425.

180. Lawrence, T. E. (1935). "Book VIII, Chapter XCII". Seven Pillars of Wisdom. pp. 508–509. The passage in the front matter is referred to with the single-word tag "Sex".

181. Lawrence, T. E. "Introduction, Chapter 1" (PDF). Seven Pillars of Wisdom.

182. Knightley and Simpson, 1970, p. 221.

183. Simpson, Colin; Knightley, Phillip (June 1968). "John Bruce (the pieces appeared on the 9th, 16th, 23rd, and 30th of June, and were based mostly on the narrative of John Bruce)". Sunday Times.

184. Knightley and Simpson, p. 29

185. Wilon, 1989, chapter 34.

186. Meyers, Jeffery "Lawrence: The Mechanical Monk" pages 124–136 from The T. E. Lawrence Puzzleedited by Stephen Tabachnick, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984 page 134.

187. Mack, 1976, p. 420.

188. Mack, 1976, p. 33.

189. Lawrence, T. E. (1997). Seven Pillars of Wisdom (Wordsworth Classics of World Literature). Wordswroth. pp. vi, vii. ISBN 978-1853264696. Introduction by Angus Calder, who says that returning soldiers often feel intense guilt at having survived when others did not, even to the point of self-harm.

190. Aldington, 1955, p. 13

191. Aldington, 1955, p. 27.

192. Aldington, 1955, p. 266-67

193. Aldington, 1955, p. 253.

194. Aldington, 1955, p. 134.

195. Aldington, 1955, pp. 25-26.

196. Crawford, 1998, p. 66

197. "T.E. Lawrence Issue Rallies His Friends". New York Times. 15 February 1954. Retrieved 21 July2020.

198. Crawford, 1998, p. 119.

199. Crawford, 1998, pp. xii, 120.

200. Crawford, 1998, p. 174.

201. David Murphy (2008). "The Arab Revolt 1916–18: Lawrence sets Arabia ablaze". p. 86. Osprey Publishing, 2008

202. "Dorset's oldest church". BBC. 5 August 2012.

203. Knowles, Richard (1991). "Tale of an 'Arabian knight': the T. E. Lawrence effigy". Church Monuments. 6: 67–76.

204. "This house was the home of T. E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia) from 1896–1921". Open Plaques. Retrieved 5 August 2012

205. "T. E. Lawrence "Lawrence of Arabia" 1888–1935 lived here. Open Plaques. Retrieved 5 August 2012

206. Matt Wells, media correspondent. "The 100 greatest Britons: lots of pop, not so much circumstance | Media". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

207. "PICTURES AND PERSONALITIES". The Mercury. Hobart, Tas. 15 June 1935. p. 13. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

208. T. E. Lawrence on IMDb

209. T. E. Lawrence on IMDb

210. McGurk, Stuart (12 May 2017). "Alien: Covenant is great – but the aliens are the worst thing about it". GQ. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

211. "Baka-Updates Manga – T.E. Lawrence". www.mangaupdates.com.

212. Jessop, Paula. "Gwendolyn MacEwen". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

213. T. E. Lawrence on IMDb

214. A Dangerous Man: Lawrence After Arabia on IMDb

215. The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles on IMDb

216. "Istikana – Lawrence Alarab... Al-Khdi3a – Episode 1". Istikana.

217. Western Morning News 1986

218. Gaisford, Sue (6 August 2000). ""Nearly 40 years on and Bennett is having another attack of nostalgia"". The Sunday Times.

219. Korda, 2010, pp. 670–671.

220. Massicotte, Stephen (2007). Oxford Roof Climber's Rebellion Paperback. Theatre Communications Group – Playwrights Canada Press. ISBN 978-0887544996.

221. ""The Warrior and The Poet"". Raymondsargent.com. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

222. "Book theatre tickets at Chichester". 25 November 2018.

223. "Linköpings Studentspex: Lawrence i Mumiedalen". 21 July 2019.

Sources· Aldington, Richard (1955). Lawrence of Arabia: A Biographical Enquiry. London: Collins. ISBN 978-1122222594.

· Anderson, Scott (2013). Lawrence in Arabia: War, Deceit, Imperial Folly and the Making of the Modern Middle East. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-53292-1.

· Armitage, Flora (1955). The Desert and the Stars: a Biography of Lawrence of Arabia. illustrated with photographs, New York, Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 9780000005779.

· Asher, Michael (1998). Lawrence. The Uncrowned King of Arabia. Viking.

· Brown, Malcolm; Cave, Julia (1988). A Touch of Genius: The Life of T. E. Lawrence. London, J. M. Brent.

· Brown, Malcolm (2005). Lawrence of Arabia: the Life, the Legend. London, Thames & Hudson: [In association with] Imperial War Museum. ISBN 978-0-500-51238-8.

· Brown, Malcolm (1988). The Letters of T. E. Lawrence.

· Brown, ed., Malcolm (2005). Lawrence of Arabia: The Selected Letters. London.

· Carchidi, Victoria K. (1987). Creation Out of the Void: the Making of a Hero, an Epic, a world: T. E. Lawrence. U. Pennsylvania, Ann Arbor, MI University Microfilms International.

· Ciampaglia, Giuseppe (2010). Quando Lawrence d'Arabia passò per Roma rompendosi l'osso del collo. Roma: Strenna dei Romanisti, Roma Amor edit.

· Crawford, Fred D. (1998). Aldington and Lawrence of Arabia: A Cautionary Tale. Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0-8093-2166-1.

· Graves, Richard Perceval (1976). Lawrence of Arabia and His World. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0500130544.

· Graves, Robert (1934). Lawrence and the Arabs. London: Jonathan Cape.

· Graves, Robert (1928). Lawrence and the Arabian Adventure. New York: Doubleday, Doran.

· Hoffman, George Amin. T. E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia) and the M1911.[permanent dead link]

· Hulsman, John C. (2009). To Begin the World over Again: Lawrence of Arabia from Damascus to Baghdad. New York, Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-61742-1.

· Hyde, H. Montgomery (1977). Solitary in the Ranks: Lawrence of Arabia as Airman and Private Soldier. London, Constable. ISBN 978-0-09-462070-4.

· James, Lawrence (2008). The Golden Warrior: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia. Skyhorse Publishing, New York. ISBN 978-1-60239-354-7.

· Knightley, Phillip; Simpson, Colin (1970). The Secret Lives of Lawrence of Arabia. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-1299177192.

· Korda, Michael (2010). Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia. Harper. ISBN 978-0-06-171261-6.

· Lawrence, A. W. (1967) [1937]. T. E. Lawrence by His Friends: insights about Lawrence by those who knew him. Doubleday Doran.

· Lawrence, M.R. (1954). The Home Letters of T E Lawrence and his Brothers. Oxford.

· Lawrence, T. E. (1926). Seven Pillars of Wisdom (1926 Subscribers' Edition). ISBN 978-0-385-41895-9.

· Lawrence, T. E. (1935). Seven Pillars of Wisdom (1935 Doubleday Edition). ISBN 978-0-385-07015-7.

· Lawrence, T. E. (2003). Seven Pillars of Wisdom: The Complete 1922 Text). ISBN 978-1-873141-39-7.

· Leclerc, C (1998). Avec T E Lawrence en Arabie, La Mission militaire francaise au Hedjaz 1916–1920. Paris.

· Leigh, Bruce (2014). T. E. Lawrence: Warrior and Scholar. Tattered Flag. ISBN 978-0954311575.

· Mack, John E. (1976). A Prince of Our Disorder: The Life of T. E. Lawrence. Boston, Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-54232-6.

· Marriott, Paul; Argent, Yvonne (1998). The Last Days of T E Lawrence: A Leaf in the Wind. The Alpha Press. ISBN 978-1898595229.

· Meulenjizer, V (1938). Le Colonel Lawrence, agent de l'Intelligence Service. Brussels.

· Meyer, Karl E.; Brysac, Shareen Blair (2008). Kingmakers: the Invention of the Modern Middle East. New York, London, W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-06199-4.

· Mousa, Suleiman (1966). T. E. Lawrence: An Arab View. London, Oxford University Press.

· Norman, Andrew (2014). Lawrence of Arabia and Clouds Hill. Halsgrove. ISBN 978-0857042477.

· Norman, Andrew (2014). T. E. Lawrence: Tormented Hero. Fonthill Media. ISBN 978-1781550199.

· Nutting, Anthony (1961). Lawrence of Arabia: The Man and the Motive. London, Hollis & Carter.

· Ocampo, Victoria (1963). 338171 T. E. (Lawrence of Arabia). London.

· Orlans, Harold (2002). T. E. Lawrence: Biography of a Broken Hero. Jefferson, North Carolina, and London, McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1307-2.

· Paris, T.J. (September 1998). "British Middle East Policy-Making after the First World War: The Lawrentian and Wilsonian Schools". Historical Journal. 41 (3): 773–793. doi:10.1017/s0018246x98007997.

· Penaud, Guy (2007). Le Tour de France de Lawrence d'Arabie (1908). Editions de La Lauze (Périgueux), France. ISBN 978-2-35249-024-1.

· Rosen, Jacob (2011). "The Legacy of Lawrence and the New Arab Awakening" (PDF). Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs. V (3). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

· Sarindar, François (2011). "La vie rêvée de Lawrence d'Arabie: Qantara". Institut du Monde Arabe (in French). Paris, France (80): 7–9.

· Sarindar, François (2010). Lawrence d'Arabie. Thomas Edward, cet inconnu. Editions L'Harmattan, collection ″Comprendre le Moyen-Orient″ (Paris), France. ISBN 978-2-296-11677-1.

· Sattin, Anthony (2014). Young Lawrence: A Portrait of the Legend of a Young Man. John Murray. ISBN 978-1848549128.

· Simpson, Andrew R.B. (2008). Another Life: Lawrence after Arabia. The History Press. ISBN 978-1-86227-464-8.

· Stang, ed., Charles M. (2002). The Waking Dream of T. E. Lawrence: Essays on His Life, Literature, and Legacy. Palgrave Macmillan.

· Stewart, Desmond (1977). T. E. Lawrence. New York, Harper & Row Publishers.

· Storrs, Ronald (1940). Lawrence of Arabia, Zionism and Palestine.

· Thomas, Lowell (2014) [1924]. With Lawrence in Arabia. Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1295830251.

· Wilson, Jeremy (1989). Lawrence of Arabia: The Authorised Biography of T. E. Lawrence. ISBN 978-0-689-11934-7.

External links· Works by T. E. (Thomas Edward) Lawrence at Faded Page (Canada)

· Footage of Lawrence of Arabia with publisher FN Doubleday and at a picnic

· Lawrence of Arabia: The Battle for the Arab World, directed by James Hawes. PBS Home Video, 21 October 2003. (ASIN B0000BWVND)

· T. E. Lawrence Studies, maintained by Lawrence's authorised biographer Jeremy Wilson

· The T. E. Lawrence Society

· T. E. Lawrence's Original Letters on Palestine Shapell Manuscript Foundation

· Works by T. E. Lawrence

· Works by or about T. E. Lawrence at Internet Archive

· T. E. Lawrence's Collection at The University of Texas at Austin's Harry Ransom Center

· The Guardian 19 May 1935 – The death of Lawrence of Arabia

· The Legend of Lawrence of Arabia: The Recalcitrant Hero

· "Creating History: Lowell Thomas and Lawrence of Arabia" online history exhibit at Clio Visualizing History.

· T. E. Lawrence: The Enigmatic Lawrence of Arabia article by O'Brien Browne

· Lawrence of Arabia: True and false (an Arab view) by Lucy Ladikoff

· Europeana Collections 1914–1918 makes 425,000 World War I items from European libraries available online, including manuscripts, photographs and diaries by or relating to Lawrence

· T. E. Lawrence's Personal Manuscripts and Letters

· Newspaper clippings about T. E. Lawrence in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

· T. E. Lawrence at Find a Grave