by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/9/20

City of Ten Thousand Buddhas 萬佛聖城

The mountain gate to the city

Religion

Affiliation: Chan Buddhism

Ownership: Dharma Realm Buddhist Association

Location: 4951 Bodhi Way, Ukiah, California, United States

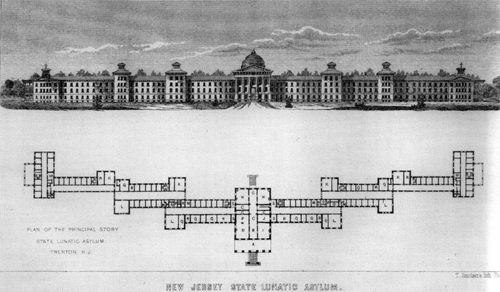

Style: Kirkbride Plan

1848 lithograph of the Kirkbride design of the Trenton State Hospital

The Kirkbride Plan was a system of mental asylum design advocated by Philadelphia psychiatrist Thomas Story Kirkbride (1809–1883) in the mid-19th century. The asylums built in the Kirkbride design, often referred to as Kirkbride Buildings (or simply Kirkbrides), were constructed during the mid-to-late-19th century in the United States. The structural features of the hospitals as designated by Dr. Kirkbride were contingent on his theories regarding the healing of the mentally ill, in which environment and exposure to natural light and air circulation were crucial. The hospitals built according to the Kirkbride Plan would adopt various architectural styles, but had in common the "bat wing" style floor plan, housing numerous wings that sprawl outward from the center.

The first hospital designed under the Kirkbride Plan was the Trenton State Hospital in Trenton, New Jersey, constructed in 1848. Throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century, numerous psychiatric hospitals were designed under the Kirkbride Plan across the United States. By the twentieth century, popularity of the design had waned, largely due to the economic pressures of maintaining the immense facilities, as well as contestation of Dr. Kirkbride's theories amongst the medical community.

Numerous Kirkbride structures still exist today, though many have been demolished or partially-demolished and repurposed. At least 30 of the original Kirkbride buildings have been registered with the National Register of Historic Places in the United States, either directly or through their location on hospital campuses or in historic districts.

-- Kirkbride Plan, by Wikipedia

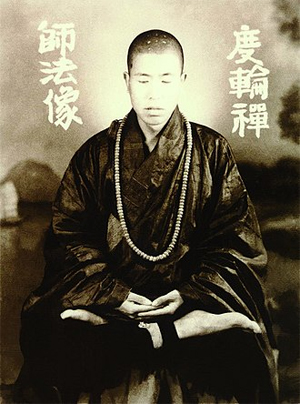

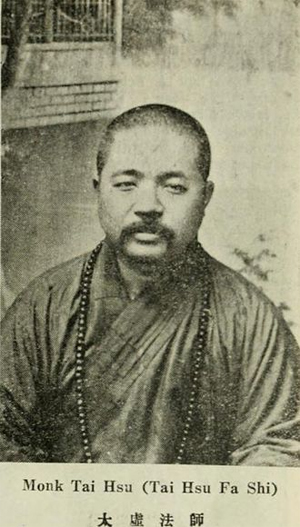

Founder: Hsuan Hua

Date established: 1974; 46 years ago

Groundbreaking: 1925[1]

Completed: 1933[1]

Construction cost: $331,545[1]

Direction of façade: South

Site area: 700 acres (280 hectares)

Elevation: 627 ft (191 m)[2]

Website: http://www.cttbusa.org

Aerial view of the city

The City of Ten Thousand Buddhas (traditional Chinese: 萬佛聖城; ; pinyin: Wànfó Shèngchéng; Vietnamese: Chùa Vạn Phật Thánh Thành) is an international Buddhist community and monastery founded by Hsuan Hua, an important figure in Western Buddhism. It is one of the first Chan Buddhist temples in the United States, and one of the largest Buddhist communities in the Western Hemisphere.

The city is situated in Talmage, California, a rural community in southeastern Mendocino County about 2 miles (3.2 km) east of Ukiah and 110 miles (180 km) north of San Francisco. It was one of the first Buddhist monasteries built in the United States. The temple follows the Guiyang school of Chan Buddhism, one of the Five Houses of Chan. The city is noted for its close adherence to the vinaya, the austere, traditional Buddhist monastic code.

History

The Dharma Realm Buddhist Association purchased the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas site in 1974 and established an international center there by 1976.[3] In 1979, the Third Threefold Ordination Ceremony at the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas was held, in which monks from China, Vietnam, Sri Lanka and the US transmitted the precepts. It was considered unique, as it represented both the Mahayana and Theravada traditions.[4][5]

Originally the site housed the Mendocino State Asylum for the Insane (later renamed the Mendocino State Hospital), founded in 1889. There were over seventy large buildings, over two thousand rooms of various sizes, three gymnasiums, a fire station, a swimming pool, a refuse incinerator, fire hydrants, and various other facilities. A paved road wound its way through the complex, lined with tall street lamps and trees planted during the asylum's initial construction. The connections for electricity and pipes for water, heating, and air conditioning were all underground, but centrally controlled.

Considering the natural surroundings to be ideal for cultivation, Hsuan Hua visited the valley three times and negotiated with the seller many times. He wanted to establish a center for propagating the Buddhadharma throughout the world and for introducing the Buddhist teachings, which originated in the East, to the Western world. Hsuan Hua planned to create a major center for world Buddhism, and an international orthodox monastery for the purpose of elevating moral standards and raising people's awareness.

The city comprises 488 acres (197 hectares) of land, of which 80 acres (32 hectares) are developed. The rest of the land includes meadows, orchards, and forests. Large institutional buildings and smaller residential houses are scattered over the west side of the campus. The main Buddha hall, monastic facilities, educational institutes, administrative offices, the main kitchen and dining hall, Jyun Kang Vegetarian Restaurant, and supporting structures are all located in this complex.

In 2009, the walls of the Long Life Hall suffered structural damage caused by an electrical fire. However, no major damage occurred to the altar, artwork or statues inside the hall.[6]

Notable structures

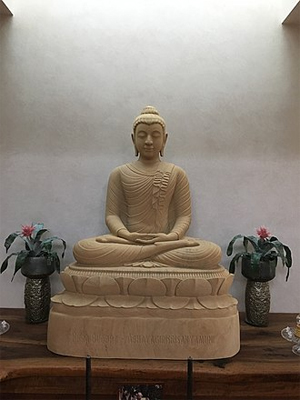

The Jeweled Hall of 10,000 Buddhas

• The Jeweled Hall of 10,000 Buddhas: Finished in 1982, the hall is adorned with streamers, banners, lamps and has in the center a 20-foot (6 m) statue of a thousand-armed Avalokiteśvara (a bodhisattva popularly known as Guanyin in Chinese and Chenrezik in Tibetan). Rows of yellow bowing cushions line the red carpet. Walls are adorned with 10,000 images of the Buddha, molded by Hsuan Hua.[7]

• Hall of No Words: This is where Hsuan Hua often held classes for his disciples in the early years of the city. The abbot's quarters, where Hsuan Hua dwelled, were on the second floor. This was also where Hsuan Hua lay in state during the 49-day mourning period. Now, it is a memorial hall that contains relics of the Buddha, Hsu Yun, and Hsuan Hua. It is closed to the public and opened on special days.

• Dharma Realm Buddhist University: DRBU was established in 1976 by Venerable Master Hsuan Hua, who devoted his life to education in developing the human character. The University offers two degree programs: Bachelor of Liberal Arts[8] and Master of Arts in Buddhist Classics.[9] In 2018, it became accredited by the Western Association of Schools and Colleges.[10]

• Jyun Kang Vegetarian Restaurant: The university cafeteria, which serves only vegan food. The goal is to serve healthful nutritious food full of the good karma of non-harming.

• Tathāgata (Rulai) Monastery: The dorm rooms for monks (left home persons) and male lay persons persuaded toward the monastic lifestyle.

• Great Compassion Courtyard: Dorm rooms for guests and visitors.

• Bell and Drum House: Houses the instruments that are played daily to ready monastics for daily practice.

• Institute for the Translation of Buddhist Texts: This facility was active in the early years of the city as a center for translation and as a residence hall for nuns and laywomen. The Institute has since moved to Burlingame, California.[11]

• Tower of Blessings: Hsuan Hua allocated the Tower of Blessings as a home for the elderly monastics residing in the city.

• Wonderful Words Hall: Site for daily gatherings to listen to Hsuan Hua's taped lectures in the 10,000 Buddhas Hall.

• Five Contemplations Dining Hall: Completed in 1982, it is where the monastics and resident lay community follow the formal monastic style in taking their lunch meal. Only purely vegetarian food is served here, and the hall can seat over 3,000 people.

• Instilling Goodness Elementary and Developing Virtue Secondary Schools: The elementary (kindergarten through 6th grade) and secondary (7th grade through 12th grade) schools were founded by Hsuan Hua in 1976. The schools are divided into two divisions, Boys and Girls, and teach such classes as meditation, yoga, Buddhism, and World Religions. Many foreign and non-local students also reside on campus in school dorms for the duration of the school year (excepting winter, spring, and summer vacations). As of spring 2006, there were about 130 students in both divisions.

• Organic Farm: A ten-acre CCOF-certified organic farm, whose produce supplements the meals in the dining hall.

The Five Contemplations Dining Hall, with a forty-foot-high painting of thousand-armed Avalokiteśvara

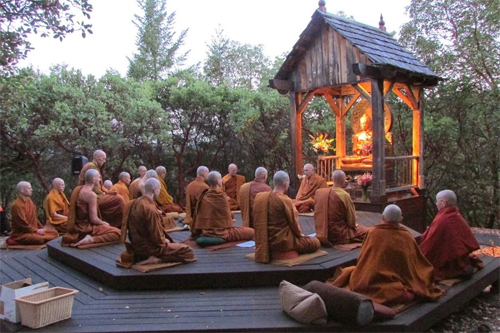

Traditions

Two practices distinguish the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas from many other Chinese Buddhist monasteries: the monastics always wear the long sashes that are worn outside the kāṣāya or monastic clothing, and they eat only one meal a day, always before noon.

At night most of them sit up and rest, rather than lying down to sleep. Monastics at the city do not have any social lives, nor do men and women intermingle. Whereas many ordinary Chinese monks go out to perform rituals for events such as weddings or funerals, none of these monks do so. Some monastics even choose to maintain a vow of silence, for varying periods of time. They wear a tag saying "No Talking" and do not speak with anyone.

There are monks and nuns who maintain the precept of not owning personal wealth and not touching money, thus eliminating the thought of money and increasing their purity of mind. Master Hsuan Hua often reminded his disciples:[12][13]

In cultivation, we have to stick to our principles! We can't forget our principles. Our principles are our goal. Once we recognize our goal, forward we go! We've got to be brave and vigorous. We can't retreat. As long as we are vigorous and not lax in ordinary times, we could become enlightened any minute or any second. So by no means should we let ourselves be confused by thoughts, and miss the opportunity to get enlightened.

— Venerable Master Hsuan Hua

Atmosphere

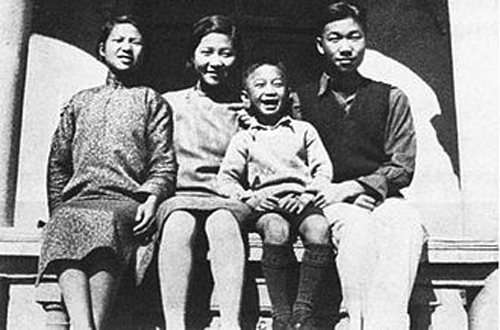

The City of Ten Thousand Buddhas is a strict Buddhist monastery adhering to the traditional Asian monastic culture although it is located in a liberal area of California. While the traditionalists are more drawn to the spiritual and devotional side of Buddhism, Westerners are often more interested in meditation. Some of the boarding school children are Westerners from the local community who want their children to grow up in a community-oriented place, while some of the children come from Taiwan and China, and even from European countries, such as France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, where parents think highly of Hsuan Hua.[14]

The monastery houses both male and female Sangha, students from the boarding school, and is open to the public. However, males and females have separate campuses, with gender-neutral buildings in the middle of the campus. In contrast, many monasteries in China, Taiwan, and the West house only monks or only nuns (but not both), and are closed to the public.

Guiding principles and customs

Hsuan Hua set up the six principles for all monastics and lay practitioners to follow as guidelines for spiritual development. These principles were "not to fight nor be greedy, not to seek nor be selfish, not to pursue personal advantage, and not to lie."

Since spiritual development is a full-time endeavor, certain rules and customs are followed in the community, including:

• Different sections of the campus are designated for men or women, and generally the genders do not commingle. This is particularly noticeable at ceremonies and meals, where men and women separate into different sections.

• Out of respect to the lifestyle of the monastics, modest clothing is worn by the laity at all times.

• Smoking, drug use, and the consumption of meat products and alcoholic beverages are prohibited.

Other notable customs:

• Unlike in many temples found in Asia, no incense is ever offered personally by any of the lay practitioners and guests. Hsuan Hua believed that it was superstitious to insist on personally offering incense to the Buddhas and pointed out that high-quality incense is expensive while poor-quality incense can ruin the walls and statues. Instead, a single stick of incense is offered by a monastic for the entire assembly, and then all practitioners would simply bow and pay respects.

Wildlife

One of the city's many peacocks

Many animals roam the grounds of the City, including peafowl, deer, squirrels, and other species. The peacocks are generally quite accustomed to the presence of people and are tame. The peacocks pose a large problem on the farm, so countermeasures have been taken against them, including covering the plants, moving the peacocks to a walnut farm, and planting extra food based on the assumption that a significant fraction will be eaten or damaged by peacocks. During special Dharma Assemblies, a Liberating of Life ceremony is held, in which many animals – especially pheasants and chukar partridges – bought from hunting preserves, are set free.

Daily schedule

Morning schedule

4:00 AM - 5:00 AM: Morning Recitation

5:00 AM - 6:00 AM: Universal Bowing

6:00 AM - 7:00 AM: Meditation / Self-study

6:15 AM - 6:45 AM: Breakfast

7:00 AM - 8:00 AM: Avatamsaka Sutra recitation (in Chinese)

8:00 AM - 10:30 AM: Classes, study or work

10:30 AM - 12:00 PM: Meal Offering / Lunch

Evening schedule

6:30 PM - 7:30 PM: Evening Recitation

7:30 PM - 9:40 PM: Lecture / Closing recitation

"Largest in Western Hemisphere" claim

Hsi Lai Temple, associated with Fo Guang Shan and located in Hacienda Heights in Southern California, has claimed since 1988 that they are the largest Buddhist temple in the Western Hemisphere. However, the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas has over 80 acres (32 hectares) of developed land on a total of 488 acres (197 hectares) compared to Hsi Lai's dense temple complex on 15 acres (6.1 hectares). Therefore it is unclear which is the largest, as there is a significant difference between the structure and location of the two Buddhist organizations.

See Also

• Buddhism in the United States

References

1. "Mendocino State Hospital - Asylum Projects". http://www.asylumprojects.org. Retrieved 2019-09-22.

2. "Talmage". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. 1981-01-19. Retrieved 2019-09-22.

3. In Memory of the Venerable Master Hsuan Hua. Buddhist Text Translation Society. 1995. p. 26. ISBN 9780881395518.

4. "Footsteps of an Ascetic Monk". City of 10,000 Buddhas. Retrieved 2019-09-22.

5. "A Year-By-Year Record Of The Life Of Venerable Master Hua And The Activities Of Dharma Realm Buddhist Association". Dharma Realm Buddhist Association. Retrieved 2019-09-22.

6. "Fire at City of 10,000 Buddhas". Ukiah Daily Journal. 2009-01-28. Archived from the original on 2017-04-27. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

7. "Hall of Ten Thousand Buddhas". City of 10,000 Buddhas. Retrieved 2014-09-10.

8. "Undergraduate Program". Dharma Realm Buddhist University. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

9. "Graduate Program". Dharma Realm Buddhist University. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

10. "Dharma Realm Buddhist University". WASC Senior College and University Commission.

11. "About Us". Buddhist Text Translation Society. Archived from the original on 2016-10-14. Retrieved 2014-09-10.

12. "History & Background". City of 10,000 Buddhas. Archived from the original on 2019-03-13. Retrieved 2019-09-22.

13. "The City of Ten Thousand Buddhas at Wonderful Enlightenment Mountain - In Memory of the Venerable Master Hsuan Hua". Dharma Realm Buddhist Association. Archived from the original on 2019-09-22. Retrieved 2019-09-22.

14. "Education: Teaching People to Love the Country, Love the Family, and Cherish Life". City of 10,000 Buddhas. Retrieved 2019-09-22.

External links

• Official website