by Marjory Harper [Marjory Harper has a Ph.D. from the University of Aberdeen in Scotland where she is employed as a lecturer in history. Her main publications are two books on emigration, entitled "Emigration from NorthEast Scotland," volume I, "Willing Exiles," and volume II, "Beyond the Broad Atlantic" (1988). Her current research interests include interwar emigration from Scotland (1919-1939), the social welfare work of the Countess of Aberdeen, and computer-based research into the backgrounds, university experiences, and subsequent careers of students at Aberdeen University in the nineteenth century.]

The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Volume 95, July 1991-April, 1992

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY NORTHEAST SCOTLAND, AND THE CITY OF Aberdeen in particular, came to enjoy an international reputation in the granite industry. This owed much to a flourishing export trade with the United States, particularly in tombstones and similar memorials. But Aberdeen did not export only its dressed and polished stone; many of the quarrymen and especially the masons responsible for these products also found their way to the U.S.A. The majority congregated in the easily accessible New England states, but some went further afield, to the Midwest, California, and Texas. Scots immigrants, settling singly or in small groups, had played an important part in the early history of Texas, but the best-known-and most notorious-influx occurred in 1886, when a large contingent of masons was brought out to cut stone for the new Texas State Capitol in Austin.1

Once the United States began to develop its own granite industry after the Civil War, it became interested in purchasing the well-known skills of quarrymen and masons from Scotland. American labor at this time was inadequate and expensive, and Scottish masons in particular were offered good wages to come over and train a native labor force. Although immigrants were also brought in from Cornwall, Devon, and Wales, the majority of the British workmen were Scots, probably mostly from Aberdeen, and it was by no means unusual for around two hundred granite tradesmen to be lured away from the city each spring to the American quarries and stoneyards.2 Some settled down permanently, perhaps establishing their own businesses after a time, while others preferred to invest the money they earned in the subsequent opening of a yard back in Aberdeen. But many continued to commute annually across the Atlantic, returning home temporarily in the winter, then re-emigrating in spring at the opening of each succeeding season.

Although the American employers wanted to exploit the Scots' skills in order to develop their own native granite industry, the arrival of these foreign tradesmen was not universally welcomed. Edmund Stevenson, one of the emigrant commissioners at New York, criticized the parasitic attitude of many transient immigrants when he wrote in 1890 that

hundreds and thousands of skilled mechanics -- stone-cutters, stone-masons, glass-blowers, locomotive engineers -- come regularly to this country every spring, year after year, and stay here until about November. They pay no taxes for our schools, they perform no jury duty, nor are they liable to; they do not perform any of the duties of citizenship, except the protection they get from the city or the stale wherever they reside. During all the working season, they are sending their money back home to their wives, their children, and their parents, and at the end of the working season they pack their grip sacks and go back to Europe, spend the winter, and the next year come back here again, and repeat the same thing over and over again. They come into direct competition with American labour; they drive out American labour by their coming here, skilled workmen that they are, and they generally work under the price of American labour. But they earn much more money here, and they can afford to go back there and live for a few months until the working season, and then come back here.3

The way in which employers used immigrants to repress wages, break strikes, and destroy attempts at union organization was most bitterly resented by many branches of American labor. In 1885 the growing hostility took legislative form when Congress, largely at the instigation of the Knights of Labor, passed the Alien Contract Labor Law. This act was designed to prevent the introduction into the U.S.A. of foreign contract workers to perform work that was the prerogative of native labor. As a result it became unlawful for any person, company, partnership or corporation, in any manner whatsoever to prepay the transportation or in any way assist or encourage the importation or migration of any alien or aliens, and any foreigner or foreigners into the United States, its Territories, or the District of Columbia, under contract or agreement ... made previous to the importation of such [people] to perform labour or service of any kind in the United States.4

Guilty parties were to be liable to a fine of $1,000 in respect of each immigrant illegally introduced, while ships' captains who knowingly transported them were to be fined $500 per immigrant and were also to bear the expense of returning them to their place of origin. In practice, however, the act was easily evaded and failed to eradicate the problems that it was meant to solve5 [Failure to define the precise categories to be excluded caused confusion in interpreting the act, successive court interpretations, and many loopholes. For instance, employers could have contract workers shipped to the U.S.A. as cabin passengers, since only steerage passengers were inspected under the law, or they could persuade members of their existing labor force to write home encouraging "friends and relatives" (who were exempt from the law) to come out on the assurance of work. Contract laborers could also be trained in advance to answer official questions in a way that would avoid detection at the port of arrival. See Charlotte Erickson, "American Industry and the European Immigrant," 1860-1885 (Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press, 1957), 170-171, 172 (quotation)]; since most immigrants did not enter the U.S.A. as contract laborers and did not therefore fall within the remit of the act, the use of aliens to break strikes and keep wages down continued almost unabated.6 [The act had been urged on the government primarily by a small union of skilled craftsmen within the Knights of Labor, the window-glass workers, whose position was threatened by the introduction of contract workers from Europe. They harnessed to their campaign the growing resentment of the American Labor movement in general against the misuse of imported labor, by suggesting -- erroneously -- that immigrant strikebreakers were generally brought in under contract. In this way the wider labor movement (which had not formulated precise proposals for dealing with its problems) was persuaded to support legislation that was much too narrow to meet its needs. The Contract Labor Law applied only to a small minority of highly skilled immigrants who were brought in to perform specific jobs, and failed to restrict the importation of undesirable immigrants to break strikes and lower wages. For further details on the act and its limitations, see Erickson, "American Industry and the European Immigrant," especially chapters 9 and 10.]

Until 1906 the American Granite Cutters' Union repeatedly rebuffed suggestions from its Aberdeen counterpart that it should agree to the interchangeability of union cards and benefits. These proposals were rejected on the grounds that since the emigrant traffic was one-sided, the concessions would benefit only the Scots. There was opposition to any proposal to exchange cards with a union whose entry fees were much lower than those of its American counterpart, and criticism of those emigrants who did not become citizens of the U.S.A., but who continued to send home the bulk of their earnings.7

On the whole, though, as far as the granite trade was concerned, emigrants from northeast Scotland seem to have worked fairly harmoniously alongside their American counterparts. A number of Aberdeen emigrants played an active part in the American Granite Cutters' Union, and opportunities for Scottish granite tradesmen in the U.S.A. were periodically publicized in the union's journal. It also regularly issued warnings against going to places where work was scarce or where there were industrial disputes, and immigrants were sometimes asked not to flood the American labor market too early in the season, before satisfactory agreements had been made between the employers and the union.8 Prospective emigrants were warned not to believe the false promises of agents who were sent to Aberdeen to recruit labor for strike-bound American quarries and yards. For much of 1887, for instance, the American Granite Cutlers' National Journal warned tradesmen to keep away from Boston, where union members had been locked out by their employers. When it became known that the employers had advertised in Aberdeen for men, offering inducements that, according to the union, they did not intend to fulfil, the American union made sure that notices appeared in the Aberdeen press reiterating the plea that granite workers should avoid Boston.9 In 1892 the Aberdeen Journal published the contents of a telegram from the secretary of the American Granite Cutlers' Union to his opposite number in Aberdeen, again warning Aberdonian tradesmen to keep away from the U.S.A. until a current lockout in the granite trade had ended.10 Similarly in 1904 the secretary of the union branch in Montreal asked assistance of his Aberdeen counterpart in preventing further local emigration to that city, after two Aberdeen men had arrived "not knowing the exact condition of affairs," and unaware that they had been recruited as strikebreakers.11

But although there is clear evidence of cooperation between granite workers' unions on either side of the Atlantic, on occasions the American warnings were not heeded, and the Aberdeen recruits then came into bitter conflict with the American trade unionists. Perhaps the most acrimonious incident was one that occurred in 1886 and had its origin not in one of the eastern granite centers in which the Aberdeen immigrants most commonly congregated, but in Texas. Since the incident provided the first real test of the Alien Contract Labor Act, it also attracted national attention in the United States.

In November 1875 the Texas legislature decided that a new State Capitol should be erected in Austin, through the appropriation of a large tract of public land. Since Texas, still recovering from the Civil War, had no funds to finance the project, it was specified that the building contract would be paid off solely in land, the state's one major asset. No further action was taken until February 1879, when 3,050,000 acres in the Texas Panhandle were set apart and a Capitol Board was appointed to administer the project.12 [Consisting of the state's governor, comptroller, attorney general, treasurer, and land commissioner. Fifty thousand acres of the land grant were to be sold to pay for the survey. Much of the following information about the early stages in the construction of the new Capitol has beend rawn from Frederick W. Rathjen, "The Texas State House: A Study of the Building of the Texas Capitol Based on the Reports of the Capitol Building Commissioners," in Southwestern Historical Quarterly, LX (Apr., 1957), 433-462.] In April 1879 an act to provide for building the Capitol was passed, and in November 1880 (after the land had been surveyed and valued at fifty cents per acre) the Capitol Board appointed a building superintendent and two building commissioners. Out of eleven sets of plans and specifications submitted to the commissioners by February 1881, the design of E. E. Myers of Detroit was accepted, and in July 1881 the commissioners advertised for tenders for construction, specifying that the entire payment would be made in land. The project assumed greater urgency when the old Capitol burned down on November 9, but only two bids were submitted, and on January 1, 1882, the contract for the new State Capitol was awarded to Mattheas Schnell of Rock Island, Illinois. Within twelve days he had assigned three-quarters of his interest in the project to Taylor, Babcock and Company of Chicago, and by the summer he had relinquished his entire interest to this same company.13 [J. Evetts Haley, "The XIT Ranch of Texas and the Early Days of the Llano Estacado" (Norman University of Oklahoma Press, 1967), chap. IV, "The State Capitol and its builders," 49-57. See also Forrest Crissey, "The Vanishing Range," The Country Gentleman, LXXVIII, Mar. 1, 1913. Also included in the Chicago syndicate that took over responsibility for constructing the Capitol were United States Senator Charles B. Farwell of Illinois and his younger brother John Farwell. Col. Abner Taylor was the Representative to Congress from Illinois, and his father-in-law Amos Babcock, a large landholder in Illinois, made up the fourth member of the syndicate. Their original intention was to dispose of the Panhandle grant in some speculative scheme. It was only after their failure to sell the Land that they decided to operate it as a ranch until increased immigration would raise its value and enable them to sell at a profit. The XIT Ranch was accordingly launched with the aid of $15 million raised through the London-based Capitol Freehold Land and Investment Company. For further details, see the Austin Daily Statesman, Mar. 4, 1959; and "The Texas Capitol. How it was built," The Cattleman, XLVI (Mar., 1960), 42-43, 68-70.]

The Capitol Freehold Land and Investment Company, Limited, was incorporated in London, England, late in the fall of 1884 with an authorized capital of $15 million. It was organized by John V. Farwell to raise finances to stock the XIT Ranch and to meet its tremendous operating expenses. Wealthy English bond buyers like the Earl of Aberdeen and Henry Seton-Karr were shareholders in the investment company but not in the ranch, which was operated by the Capitol Syndicate under John and Charles B. Farwell, Amos C. Babcock, and Abner Taylor. By the late 1890s the British investors had begun clamoring for the redemption of their bonds, and the syndicate began its gradual selling of the XIT properties. The Farwell estate completed the redemption of most of these bonds to the Englishmen's satisfaction in 1909, and the investment company ceased to exist. The final account payment and dissolution of the company came in 1915. The remaining interest went to the Farwell heirs, who set up the Capitol Reservation Lands as a trust, and to shareholders in this country.

Bibliography: J. Evetts Haley, The XIT Ranch of Texas and the Early Days of the Llano Estacado (Chicago: Lakeside, 1929; rpts., Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1953, 1967). William D. Mauldin, History of Dallam County, Texas (M.A. thesis, University of Texas, 1938). Lewis Nordyke, Cattle Empire: The Fabulous Story of the 3,000,000 Acre XIT (New York: Morrow, 1949. rpt., New York: Arno Press, 1977).

-- Capitol Freehold Land and Investment Company, by Texas State Historical Association

Sir Henry Seton-Karr CMG DL (5 February 1853 – 29 May 1914) was an English explorer, hunter and author and a Conservative politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1885 to 1906.

Seton-Karr was the son of George Berkeley Seton-Karr, of the Indian Civil Service; and his wife Eleanor, the daughter of Henry Usborne of Branches Park, Suffolk. He was educated at Harrow School and Corpus Christi College, University of Oxford gaining an MA in Law and was called to the bar at Lincoln's Inn in 1879.[1] Seton-Karr owned a cattle ranch (Pick Ranch) in Wyoming, USA and was a director of Capitol Freehold Land and Investment Co.[2] He was an explorer, big game hunter and writer.

Seton-Karr was elected as the Member of Parliament (MP) for St Helens in the 1885 general election and held the seat until his defeat at the 1906 general election.[3] He did not stand again in St Helens, but at the January 1910 general election he stood unsuccessfully in Berwickshire.[4]

He became a Deputy Lieutenant of Roxburghshire in 1896,[5] and was made a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) in October 1902.[6]

-- Henry Seton-Karr, by Wikipedia

John Campbell Hamilton-Gordon, 1st Marquess of Aberdeen and Temair KT KP GCMG GCVO PC (3 August 1847 – 7 March 1934), known as The Earl of Aberdeen from 1870 to 1916, was a Scottish politician. Born in Edinburgh, Hamilton-Gordon held office in several countries, serving twice as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (1886; 1905–1915) and serving from 1893 to 1898 as the seventh Governor General of Canada.[1]....

Aberdeen entered the House of Lords following his succession to his brother's earldom. A Liberal, he was present for William Ewart Gladstone's first Midlothian campaign at Lord Rosebery's house in 1879. He became Lord Lieutenant of Aberdeenshire in 1880, served as Lord High Commissioner to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland from 1881 to 1885 (he held the position again in 1915), and was briefly appointed Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in 1886.The Lord High Commissioner to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland is the British Sovereign's personal representative to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland (the Kirk), reflecting the Church's role as the national church of Scotland and the Sovereign's role as protector and member of that Church.

-- The Lord High Commissioner to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland is the British Sovereign's personal representative to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland (the Kirk), reflecting the Church's role as the national church of Scotland and the Sovereign's role as protector and member of that Church.

He became a Privy Counsellor in the same year.[4] In 1884, he hosted a dinner at Haddo House honouring William Ewart Gladstone on his tour of Scotland. The occasion was captured by the painter Alfred Edward Emslie; the painting is now in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London, given by the Marquess’ daughter, Marjorie Sinclair, Baroness Pentland, in 1953.[5]

In 1889 he was chosen as an alderman of the first Middlesex County Council, his address being given as Dollis Hill House, Kilburn, in that county.[6]

He served as Governor General of Canada from 1893 to 1898 during a period of political transition. He travelled extensively throughout the country and is described as having "transformed the role of Governor General from that of the aristocrat representing the King or Queen in Canada to a symbol representing the interests of all citizens".[7] In 1891, he bought the Coldstream Ranch in the northern Okanagan Valley in British Columbia and launched the first commercial orchard operations in that region, which gave birth to an industry and settlement colony as other Britons emigrated to the region because of his prestige and bought into the orcharding lifestyle.[8] The ranch is today part of the municipality of Coldstream, and various placenames in the area commemorate him and his family, such as Aberdeen Lake and Haddo Creek.[9][10]

He was made a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George in 1895.[11]

He was again appointed Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in 1905, and served until 1915. During his tenure he also served as Lord Rector of the University of St Andrews (1913–1916), was created a Knight Companion of the Order of the Thistle (1906), and was created a Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order (1911).[12] Following his retirement, he was created Earl of Haddo, in the County of Aberdeen, and Marquess of Aberdeen and Temair, in the County of Aberdeen, in the County of Meath and in the County of Argyll, in January 1916.[13]

He had been appointed Honorary Colonel of the 1st Aberdeenshire Artillery Volunteers on 14 January 1888 and retained the position with its successors, the 1st Highland Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, until after World War I.[14]...

From 1883 until 1896, he was also an owner of and investor in the Rocking Chair Ranche located in Collingsworth County, Texas, together with his father-in-law, The 1st Baron Tweedmouth, and his brother-in-law Edward Marjoribanks, 2nd Baron Tweedmouth.[18]

-- John Hamilton-Gordon, 1st Marquess of Aberdeen and Temair, by Wikipedia

The construction of a new Texas State Capitol was given greater urgency when the existing Capitol was destroyed by fire in November 1881. Courtesy Austin History Center, Austin Public Library

Excavations began in February 1882 and preparation of the foundation and basement occupied that year and most of 1883.14 It was intended that the superstructure should be built primarily of limestone, and by February 1884 about $100,000 had been spent in quarrying and dressing limestone boulders at the Oatmanville quarry near Austin. In March the railway for transporting the stone from the quarry to the building site was completed, and the first consignment -- about sixty tons of limestone -- was delivered, only to be rejected by the building commissioners on the grounds that it did not meet the required standard.15 [The Oatmanville stone contained too much iron pyrites, and exposure to the weather caused it to become discolored, with rusty-colored streaks. Rathjen, "The Texas State House," 442.] It subsequently became clear that Texas quarries alone could not supply enough limestone of the standard specified and contractor Abner Taylor suggested that limestone from Bedford, Indiana, be substituted for the Oatmanville product. This, however, would have required a major change in the terms of the contract and would go against the state's policy of using only Texas products. Reserves of red Texas granite near Burnet were then beginning to attract notice, and state governor John Ireland (who headed the Capitol Board) was strongly supported by public opinion when he recommended changing the specifications for the Capitol superstructure to granite. By early 1885 architect Myers had submitted an amended design plan incorporating the change to hard stone, a change whose cost was estimated at $613,865.16 Contractor Taylor was unwilling to incur these extra costs, particularly since the business depression of 1883-1885 had checked the sale to settlers of the three million acres of land awarded to his syndicate as payment for construction.17 [If immigration to Texas had continued at the rate expected when the contract was awarded, the syndicate would have benefited richly. American GCNJ, IX (Aug., 1885), 2. See also Ruth Allen, "The Capitol Boycott: A Study in Peaceful Labor Tactics, 1885-1889," in Chapters in the History of Organized Labor in Texas, University of Texas Publication No. 4142, Nov. 15, 1941 (Austin The University, 1941), 46. This paper draws not only on Allen's published work but also on many of the original sources used by Allen.]

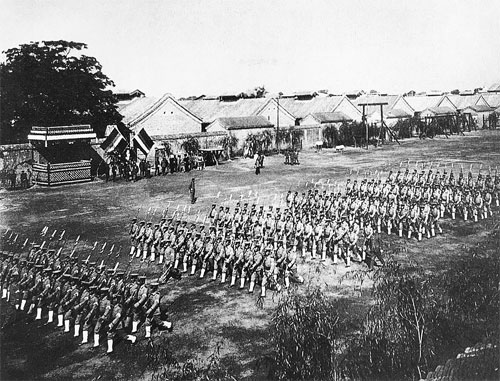

While the controversy raged, work on the Capitol came to a halt during spring and summer 1885, but the building syndicate, faced with rising costs and impatient investors, could not afford to delay indefinitely. On July 16 Taylor agreed to construct the superstructure of granite, "provided the State will furnish me a granite quarry accessible and suitable for the building, free of cost, and furnish such number of convicts as I may require, not to exceed 1000, I to board, clothe and guard them."18 He also stipulated that various structural changes be made to the building, in order to reduce its cost by at least $100,000, and that the time allowed for its completion be extended by three years. The Capitol Board quickly agreed to Taylor's propositions, a supplemental contract was drawn up on July 25, and up to five hundred convicts from state penitentiaries were assigned to the building syndicate, which was to pay sixty-five cents a day to cover the cost of feeding, clothing, and guarding them.19 The convicts were put to work in the granite quarries at Marble Falls, fifteen miles south of Burnet, and also constructed a narrow gauge railway from the quarries to join the Austin and Northwest railroad at Burnet. (The quarry owners had agreed to supply, free of charge, all the granite needed to construct the Capitol.) Shortly after these revised plans had been agreed, the Capitol syndicate sublet the contract for construction of the entire building to a young German-born builder, Gus Wilke of Chicago. Wilke had initially been employed in 1882 to put in the basement of the Capitol, and having accomplished this work satisfactorily, his contract was renewed and extended in 1885.

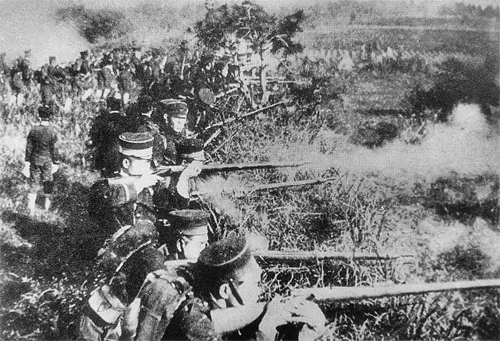

The problems that had plagued the Capitol project in its early stages were as nothing to the controversy that was to break over the use of convict labor. The opposition of public opinion in Texas was made clear in the many protests sent to the Capitol Board when the revised plans were announced.20 But much more bitter and prolonged opposition came from the American Granite Cutters' Union. It had already opposed Wilke over the use of nonunion labor, and became even more enraged when its members' financial interests were threatened by the use of a convict work force.21 Any collaboration in teaching convicts to cut granite would reduce the wages of skilled tradesmen and impede the union's efforts to achieve better conditions within the industry. These dangers were explained in the monthly circular of the Granite Cutters' Union in September 1885:

If 200 granite cutters work with, and teach 100 convicts the trade the probability is that in twelve months time there would be but 100 granite cutters and the number of convicts would be increased to 200, and in two years time there would be 300 convicts and no free granite cutters whatever employed on the job, for after the first lot is taught they will be put to teach other convicts, and thus drive out free labor altogether, for we have been reliably informed that the state officials of Texas have agreed to supply the contractors with 500 convicts.22

In December 1884 the Austin branch of the union had fixed the wage rate for its members working on the Capitol project at $4.00 per day, but Wilke subsequently offered only from $2.75 to $3.00, and only if these terms were accepted would he cease employing convicts. But his conditions were unacceptable to the Granite Cutters' Union, which was further angered by a letter from Wilke to the union, in which he had threatened to "hire any good mechanic whether he be a scab as you call it or not. I will not permit you, nor any society, to dictate whom I shall employ, whether they be convicts or free labor."23 The union voted unanimously to boycott the Capitol project, and a circular to this effect was published in Austin in December 1885, warning cutters to keep away until Wilke had stopped hiring convict labor:

Granite Cutters of America, show ... Gus Wilke and his employers ... that free men will not submit to the introduction of slavery into our trade under the guise of contract convict labor, and that you will not teach convicts our trade to enrich these schemers, who care for nothing but the almighty dollar and now seek to degrade our trade to fill their own pockets.24

The union's injunction was not universally obeyed, according to the Graniteville (Missouri) branch secretary, who declared in the Granite Cutters' National Journal in February 1886:

Regarding the Austin job I [am] informed that there are a few of the brotherhood (although they are unworthy of the name now) working there at a bill of prices far below the Austin bill of prices. They have no shed, but Wilkie [sic] has fixed up an eight-foot fence with a line of barbed wire against the top of it, and no one is allowed inside but the workmen. Think of Gus Wilkie's fine promises when he is paying such a low bill of prices as will drive all his scabs out from his barbed wire fence as soon as spring comes, and what will they do then, poor things, as their names are all known and will soon be published for the information of square men.

The citizens of Burnet are indignant at the way Wilkie is acting, as they have subscribed about $1,500 and gave him [this] on his guarantee that the stone would all be cut there by free labor. They are expressing their opinions about Gus Wilkie and very hard words, but as is well known, hard words have no effect on him as long as he can get tools and fools to do his bidding.25

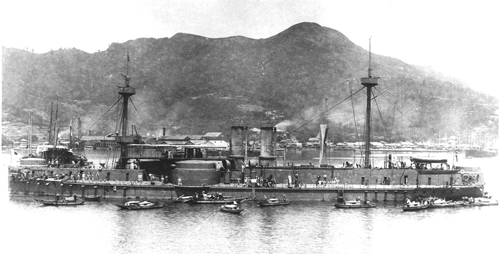

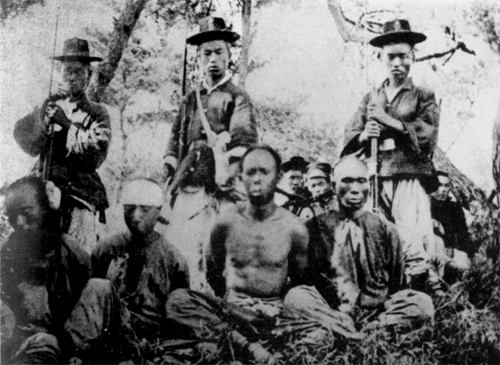

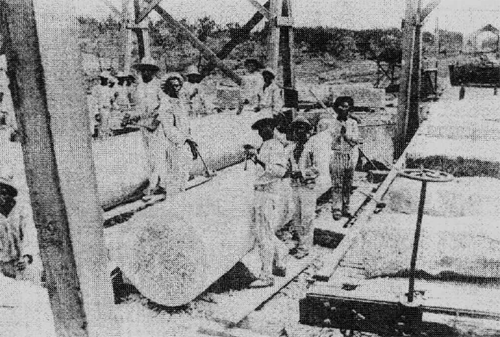

Up to 500 convicts from Texas state penitentiaries were assigned to the Capitol building syndicate and employed as granite cutters in the quarries at Marble Falls, Texas. Courtesy Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.

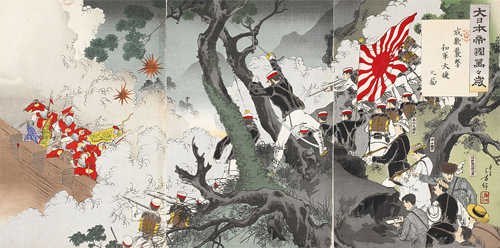

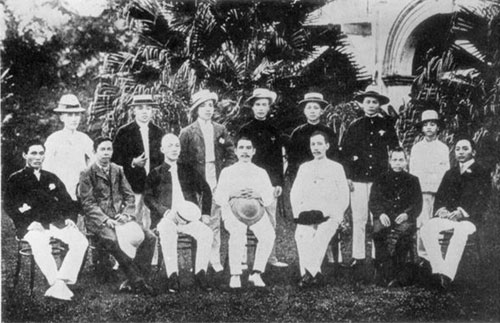

On the whole, however, the boycott was well supported, and soon caused Wilke to look abroad in search of the required skilled labor that the American union refused to supply. In April 1886 he sent his agent George Berry to Aberdeen in order to recruit 150 granite cutters and fifteen blacksmiths to complete the construction of the Capitol. For his services Berry was allegedly paid $600 and promised promotion to the post of an assistant foreman in the Burnet granite yard.26 He first advertised his requirements in the Aberdeen press, then on April 12 organized a meeting in the Northern Friendly Society Hall in the city.27 This gathering attracted an audience of 300, of whom 120 had already been recruited to go to Austin as a result of the earlier newspaper advertisement. The purpose of the meeting was to give particulars of the expedition to these recruits, as well as to invite applications for the remaining vacancies. Builder Robert Hall, presiding, drew on his own experience of four years spent in the U.S.A. to recommend the venture, particularly in view of the depression through which he said the Aberdeen granite trade was then passing.28 Details of wages and working conditions were explained by a Mr. Prescott of London, representing Gus Wilke. The recruits were promised at least eighteen months steady employment at wages of $4 to $6 per day, board and lodging at only $16 to $20 per month, and prepayment of a proportion or the whole of the £10 fare.29 [Although the men were engaged initially for only eighteen months, it was expected that their contracts would be renewed, as construction of the Capitol was expected to take another four years. Aberdeen Evening Gazette, Apr. 15, 1886.] Single men were 10 repay this advance out of their first month's wages, but married men were allowed to defer repayment until the second or third month. Recruits were required to prove their commitment to the bargain by paying "earnest money" of twenty-five shillings each, whereupon they were issued with their sailing tickets.30 [A dispute arose when two blacksmiths, having paid this sum, were then told their services were not required, since Berry had been unable to obtain his full complement of stonecutters. The two blacksmiths complained to the sheriff that they had been defrauded, whereupon Berry was arrested and held in custody for a short time until he had paid a fine of ten pounds. House Misc. Doc. No. 572, 50th Cong., 1st Sess., p. 146]

Approximately eighty-six recruits left Aberdeen with Berry on April 15 on the first stage of an eighteen-day journey to Austin, embarking the following day on the Anchor liner Circassia at Greenock.31 Under the original agreement they were to have been shipped direct to Galveston, Texas, but when Wilke found it was not only cheaper but also safer -- from his point of view -- to have them transported by coastal steamer to Norfolk, Virginia, and thence by train to Texas, the initial port of landing was changed to New York.32 On April 17 the Glasgow Weekly Mail reported (somewhat inaccurately as regards the emigrants' destination and employment) that

On Thursday afternoon 87 tradesmen arrived at Greenock by special train from Aberdeen .... The men include granite cutters and builders, who have been engaged on an 18 months' agreement to work at 4 dollars per day, in Texas, at the erection of the Court house in Galveston. The men state that their passage is to be paid out and home, and that they have a guarantee from a firm of standing in Aberdeen that they were not going out to work regarding which there is a dispute between contractors and workmen.33

Berry had thus neglected to tell his recruits that the need for their importation had arisen because of the boycott of the Austin contract by American native labor. He had admitted that convict labor was employed on the project, but declared that this had come about only because insufficient free labor was available in the U.S.A., and promised that once Wilke had secured the required number of free workers he would cease to employ prisoners.34 Given their limited understanding of the true state of affairs, it is likely that the Aberdeen recruits were totally unprepared for the reception given them on arriving at New York.

Informed by telegram of the embarkation of Berry and his recruits, three officials of the Granite Cutters' Union were sent to New York to intercept the party. In particular, they hoped to secure Berry's arrest for importing workers into the U.S.A. in violation of the Alien Contract Labor Law. Initial attempts to persuade the U.S. District Attorney at New York to have Berry arrested under this law failed for lack of immediate proof that a contract had in fact been made with the immigrants, but the union officials did manage to persuade twenty-four of the recruits not to proceed to Texas.

On returning to Castle Garden and going amongst the men and explaining matters, 24 of them decided not to go any further with Berry; but he, with the assistance of two ruffians, named Thom and Dawson, coaxed and coerced the remainder aboard the ferry-boat for the New Jersey side. Berry and his assistants dragged some of them in such a manner that the U.S. Deputy Marshal dared them to lay a linger on any of them or he would arrest them for assault and battery.35

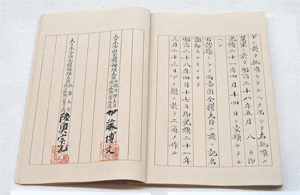

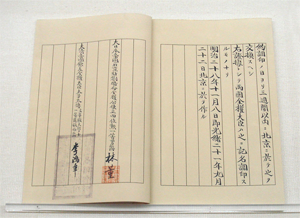

While these men were boarding the steamer Comal for Newport News, Virginia, two of the American union representatives had discovered from the men who remained in New York that the recruits had in fact been given printed contracts by Berry, which, when they were shown to immigration officials at Castle Garden, were said to be in clear violation of the Contract Labor Law. The three documents in their possession covered the conditions of their employment, accommodation, and the prepayment of their passages, and included two certificates from Gus Wilke. One of these stated that he had authorized Berry to engage and bring to Austin the granite cutlers and blacksmiths required to work on the State Capitol, and stipulated that "the fare for passage advanced by me is expected to be returned, out of earnings made by cutting."36 His other certificate gave details of the wages and accommodation to be provided for the recruits at Burnet, while the third document, a ticket issued by the Anchor Line, gave proof of the prepayment of passage as far as Galveston. When these documents were put before the district attorney, along with the affidavits of two renegade recruits (Charles Falconer and Robert Maitland), he admitted that Wilke was in breach of the law, and so the way was cleared for the American Granite Cutters' Union to initiate the prosecution of Wilke and the syndicate he represented.

Having supplied the American union with ample proof of the existence of printed contracts, the renegade recruits, with that union's blessing, sought clean jobs in the granite centers of the East, ten ultimately finding work in Vermont.37 Meanwhile, the tradesmen who had elected to proceed to Texas arrived at Burnet on May 2, the union's attempts to head them off at Norfolk and Galveston having failed. In order to avoid confrontation, they had disembarked quietly at Newport News, from where they had traveled by train, first to Houston, and then to Austin. A telegram intimating their safe arrival was despatched by four of the men and appeared in the Aberdeen Daily Free Press on May 8. It made no reference to the substantial depletion of the party at New York, but merely stated that the men had "arrived all safe, and find the job everything as represented."38 An eyewitness at Houston had described them as a "hardy and robust set of men, with plenty of bone and muscle," whose arrival had given him "the best evidence I have yet had that the capitol would be completed."39 As the Austin Daily Statesman pointed out later, the recruits were not paupers. "but on the contrary are skilled artisans, evidently capable of paying their way anywhere ... they came of their own motion ... are paid the very highest price for their labor ... and are satisfied."10

One of the recruits, granite cutter Alexander Greig, writing home to his parents on May 3, spoke of the hearty welcome the party had received in Texas and refuted claims that they had been deceived. He painted a different picture of the New York incident from that described in the Granite Cutters' National Journal, which alleged that the men had been forced to continue and had been manhandled aboard the ferryboat.41 In Greig's words:

While we were at New York, there were several of the society met us, and tried all that was in their power to get us to stop at New York; and I am sorry to say that there was a few fools amongst us who listened to what they had to say, and stayed behind to their sorrow and shame, and there was a report got into the New York newspapers which said that we were detained in New York, and that Mr. Berry was arrested, and Mr. Wilkie [sic] fined a hundred dollars, which is the biggest falsehood that ever went into any newspaper. You can tell anybody that asks about us that everything is right, and that we have been treated well. I was told that I was growing fat upon it. I am first-class in health and intend to stick in. This is the most splendid country I have ever seen. I have seen nothing to equal it through all the States.42

But not all the recruits were of the same mind, particularly once work had actually begun. Perhaps Greig too became disillusioned, for his promise in his first letter that he would send home a weekly diary to his parents did not materialize.43 According to the Galveston Daily News of May 13, many of the men, already angry at the expense incurred during their unexpected seven-day journey from New York, were soon disappointed in their expectations of high wages. It estimated that about half the recruits had had no previous experience of granite cutting, and were unable to earn even a dollar a day. In fact, the payroll vouchers for the period May 1886 to May 1887 indicate that the stonecutters earned an average wage of twenty-seven cents per hour, though individual payments varied from only four cents to fifty cents per hour.44 The blacksmiths were paid forty cents per hour, though the Galveston Daily News (May 13) alleged that these men, employed as tool sharpeners, were particularly inept. Genuine granite cutters on piece work therefore became impatient at time and money unnecessarily lost in waiting for their implements to be sharpened. Most of the men were accommodated and employed at "Wilkeville," a fenced enclosure on the southeast side of Burnet adjacent to the railway line. All but two recruits were initially boarded at a monthly charge of approximately seventeen dollars each. After May 1886, however, only a few Scots were billed for accommodation, and in September 1886 and March 1887 no deductions were made for board. According to the Galveston Daily News, the Scots soon became dissatisfied with their working conditions and accommodation:

Bitter feelings and homesickness are cropping out everywhere. Working out in the sun with the thermometer standing at 80 or 90°, and four to six men packed in a lodging room, ten feet square, along with indifferent food, is something that was not calculated on.45

This view was corroborated three months later in a circular issued by the Austin Assembly of the Knights of Labor, which alleged (in direct contradiction of the claims made by the Austin Daily Statesman) that "The work is hard, and prices and wages low, and as a consequence the stone cutters are leaving and seeking employment in other places."46 By the end of October 1886 at least three of the Scots had died, and by May 1887 the payroll vouchers show that only fifteen of the original recruits were still employed at Burnet.47 [They were George Mutch (23), died June 13, John Smith (27), drowned June 27, and George Moir (22), died October 15. Before the Scots dispersed, they commemorated these deaths by preparing and erecting a granite memorial in the cemetery at Burnet.] It had soon become evident that Wilke had no intention of keeping his promise to diminish the convict labor force once he had secured sufficient free labor. On the contrary, he almost doubled the number of convicts employed, according to one Aberdeen recruit, blacksmith David Dawson, who left the job early and who subsequently testified to Wilke's misdemeanors before the Congressional Enquiry into violations of the Contract Labor Law in 1888.48 According to the Austin Daily Statesman of July 23, 1886, Wilke at that time had 200 convicts employed at quarrying and 100 at cutting stone, in addition to 148 "free" stonecutters, making a total of 448 men at work in Marble Falls and Burnet preparing granite for use in Austin. By October 5 the number of convicts employed had risen to 350, and the newspaper predicted that by the following April all the rock required for the Capitol would have been quarried.

Before disillusionment set in, David Dawson had, at Wilke's request and on his behalf, secured a further contingent of Aberdonians to go to Austin, perhaps to replace those who had defected at New York.49 Dawson contacted a friend in Aberdeen, granite merchant John Petrie, who then advertised in the Aberdeen Journal for thirty cutters and two masons to go to Austin.50 As a result of his appeal, fifteen extra recruits left Aberdeen on June 17 to embark on the Anchor liner Turnissa at Glasgow.51 Wilke subsequently paid Petrie $15.60 for his services, but did not make use of him again, for when more stonecutting vacancies at Austin were advertised in the Aberdeen Journal on October 9, interested parties were told to apply to the newspaper office, not to Petrie. Work on the Capitol proceeded quickly during 1886 and 1887: by November 1886 Wilke's monthly payroll was almost $50,000, and by the following summer the walls and most ornamental work were finished, and the dome was taking shape.52 The Aberdeen recruits' work was coming to an end, and many of them were preparing to leave Texas.

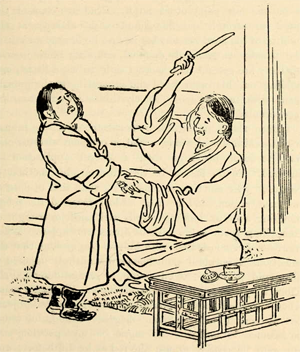

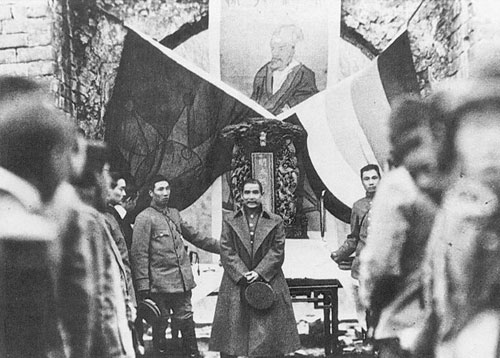

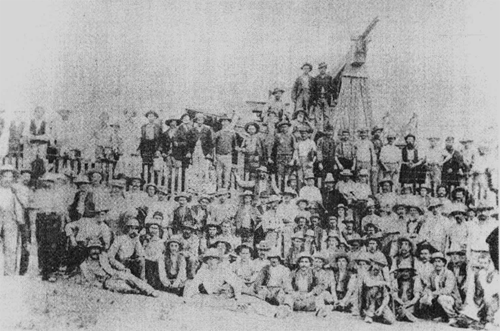

The Aberdeen recruits soon discovered that the high wages and utopian working conditions promised by Berry did not materialize, and dissatisfaction rapidly set in. Courtesy Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.

Meanwhile, however, the American Granite Cutters' Union was pursuing the prosecution of the Capitol syndicate through the Austin courts. Papers provided by the renegade recruits at New York, which clearly indicated the existence of an illegal contract involving Wilke, Berry, and the immigrants, were forwarded to Austin. In July 1886 Wilke, the Farwell Brothers, Taylor, and Babcock were accordingly indicted in the Federal District Court in Austin, charged with having violated the one-year-old Contract Labor Law. Hearing of the case was postponed until August 1887, and during the interval the union campaigned for funds to finance its prosecution, securing a grant of $5,000 from the General Assembly of the Knights of Labor.53 In March 1887 several Aberdeen recruits who expected to leave Austin before August testified on behalf of the prosecution before a Circuit Court clerk in Austin. They included George Edwards, Alexander Gregg, and James Taylor, who all intended to return to Aberdeen, Thomas Kesson from Stonehaven (bound for Georgia), Alexander Gibbs from Aberdeen (going to St. Louis), Alexander Steel from Wartle (also going to Missouri in the hope of finding work at St. Louis or Graniteville) and William Porter, one of the blacksmiths (going to Wisconsin). George Kelman, who had been in the U.S.A. on four previous occasions, hoped to find work in Texas. All the witnesses claimed that they had come to Austin on the strength of a promise of employment made to them by George Berry in Aberdeen in April 1886. Berry had shown them a letter from Gus Wilke authorizing him to recruit 150 granite cutters, whose passage money would be prepaid on condition that they subsequently repaid the sums advanced ($38-$40) out of their wages. According to Alexander Steele:

George Berry told me all about the job and about the climate, and about there being good water here and that there was shade going to be put up, and that Gus Wilke had a steam traveler that there was labourers there to turn those rocks and that we would have a big pile of rocks there which we would never have to wait for and that the quarry was fifteen miles distant and that there was a large number of convicts there some quarrying and some cutting rock and that if we would agree to come with him our passage money would be advanced all excepting one pound five shillings, which we had to pay part of it as a security that we would come when the expedition started and part of the money went for our ship kit and to transfer our baggage from Greenock station to the boat. Also that it would require at least 18 months steady granite cutting to complete cutting stone for the building and that we had to pay back our advanced fares ... I asked him [Berry] why the job was scabbed and he told me that the National Granite Cutters Union scabbed the job unjustly and that it was scabbed nearly three months before they commenced to cut rock, or before there was convicts employed but that the convicts would be discharged when we arrived at Burnet, Texas, and that was the only fault the Stone Cutters Union had against it, and that we could get board and lodging from 16 to 18 and 20 dollars per month.54

On this basis the men had made verbal agreements with Berry to work for Wilke (whom they first met in Houston on May 2). But on July 30, 1886, those still at Burnet were asked to sign a statement to the effect that they had made "no contract of any character whatsoever with Gus Wilke or with any other person for Gus Wilke to perform any service ... for Wilke previous to ... becoming a resident of the USA."55 In their testimony Steele and another witness, Andrew Durno, both admitted that they had signed this document knowing it to be false. Durno had been ill at the time and Steele had feared that refusal to sign would have meant dismissal and great hardship; "at that time I was without money and understood from others in the public papers that every union and trade organization wanted to see us starve."56

Hearing of the case was again postponed in August 1887, and when it eventually came to court two years later Wilke stood alone, the names of the members of the Capitol Syndicate having been dropped from the prosecution.57 Wilke admitted the charge of violating the Contract Labor Law and was fined the statutory penalty of $1,000 for each illegally imported worker, together with $1,000 costs, making a total penalty of $64,000. But he was given up to eighteen months' stay of execution in order to appeal to Washington, and when judgment was finally executed in 1893 he was fined only $8,000 and costs. This clemency infuriated the Granite Cutters' Union, which claimed that Wilke had pleaded guilty in order to shield the Capitol Syndicate, and that the syndicate had then used its political influence in Washington to nullify the sentence passed on its scapegoat and thus defeat the law.58 [Why, for instance, did a North Dakota senator with no obvious interest in the case request the district attorney at Austin to grant a stay of execution on his judgment against Wilke? See Federal Court, Austin District, letter of Aug. 29, 1890, from F.A. Reeve, Acting Solicitor, U.S. Department of Justice, to A.J. Evans, U.S. District Attorney, Austin District, authorizing a stay of execution on the judgment against Wilke at the request of Senator G.A. Pierce of North Dakota, in Allen, "The Capital Boycott," 82. See also American Federation of Labor, Convention Proceedings, 1889, pp. 24-25, in ibid., 85-86. The Granite Cutters' Union persuaded the American Federation of Labor to protest to President Harrison against what it saw as an evasion of the law.]

The American Granite Cutters' Union was interested not only in prosecuting the contractors but in punishing the Aberdeen tradesmen who had worked at Burnet, and throughout 1886 it mounted a sustained attack on them through its trade journal. The action of the strikebreakers was condemned as "despicable" at a time when the union was striving to secure higher wages and shorter hours within the granite industry.59 though one correspondent did observe that the ill wind that had blown the Scots to Texas had at least relieved Aberdeen of the dregs of its granite workers.60 A circular issued by the Austin Assembly of the Knights of Labor in August 1886 published the names of the strikebreakers with the warning

Mark these men, Knights of Labor, and union men of all classes. Do not work with them and have no dealings with them whatever. It is only by uniting that we can stop the working of convicts on public works. Men who work on jobs with convicts ought to be blacklisted, as they are no good to any job.

If any of these men, or men who say they have been working on the capitol building at Austin, or at Burnet or Oatmanville. come near you, let them take a walk; give them no work, and see that they get no work in your neighborhood.61

When the Austin contract ended in summer 1887, and the workmen prepared to disperse throughout the U.S.A., the Granite Cutters' National Journal reissued the list of Aberdeen recruits, along with the names of other strikebreakers not recruited by George Berry. This was again done in the hope that any of these men who sought work in other American granite centers would be remembered and cold-shouldered by the union.62

While it is not known what became of the blacklisted labor force, Wilke and Berry both made their peace with the Granite Cutters' Union in 1890, on payment of a penalty of a mere $500 each imposed by the union before it would deal with them again.63 Perhaps the protracted litigation and opposition of powerful business and political leaders had simply proved too much for the union, exhausting its funds and forcing it to drop its prosecution of the syndicate. The union certainly regarded its achievement as a rather hollow, cosmetic victory, for it had always maintained that Wilke was just the agent of the much more powerful Capitol Syndicate, and it felt that failure to secure the conviction of the syndicate itself really constituted defeat.64 [Ibid. (Allen, "The Capitol Boycott," 54.) See also San Antonio Daily Express, Aug. 2, 1888, which published a declaration by Abner Taylor that, though he had opposed the importation of the Scottish stonecutters, neither he nor any other member of the Syndicate had had the authority to prevent it.]

Nevertheless. the ramifications of the Capitol boycott extended beyond Texas and beyond the confines of the Granite Cutters' Union, to Washington itself. Since the incident provided the first real test of the Contract Labor Law, it attracted national attention and was largely responsible for an enquiry by a committee of the House of Representatives into violations of this legislation. The committee began its hearings in July 1888 (over a year before the case against Wilke finally came to trial) and the activities of the Capitol Syndicate were included in its lengthy investigations. Testimony against the contractors was led by Josiah Dyer, an English immigrant and secretary of the American Granite Cutters' Union since 1877. In "support of his claim that the Aberdeen tradesmen had been imported illegally under contract, he produced affidavits from four recruits, two of whom had left the party at New York and had not proceeded to Texas."65 Their written evidence was corroborated by two more recruits who appeared before the enquiry in person. James Anderson (who had left the party at New York) and David Dawson (who in June 1886 had acted as Wilke's agent in importing a further batch of Aberdeen tradesmen) had both since found lucrative employment in Vermont and had no intention of returning to Scotland.66

Meanwhile in Austin the troubles that had plagued the construction of the Capitol since its inception were not yet over. Building costs had doubled from the original estimate of $1,500.000 to $3,000.000.67 In 1887, drastic alterations had to be made to the design of the half-built dome, when it became clear that the original structure was likely to be dangerously heavy. Following the dedication of the Capitol on May 18, 1888, a gala and ball were under way inside the new building, when the celebrations were (quite literally) dampened by the roof leaking during a rainstorm. Allegations by W. P. Hardeman, the superintendent of building and grounds, that there were major structural defects in the roof and drains, were hotly denied by the building commissioners and the contractors.68 [Rathjen, "The Texas State House," 458-459. The commissioners claimed that Hardeman was unfamiliar with the specifications and was therefore not competent to judge the structure. Wilke pointed out to the Capitol Board that he had warned of problems with a copper roof, but having registered his protest, he had then used the materials specified in the contract. Although he insisted he was not to blame for the defective roof, he felt that any fault in the structure would damage his reputation. For this reason, together with his desire to see the contract finally settled, he himself offered to bear the cost of either replacing the copper roof with a tin one, or guaranteeing to maintain the existing roof for a period of three years.] In August 1888 contractor Abner Taylor and sub-contractor Gus Wilke tendered the building for acceptance and asked for the final settlement of their account; but Hardeman enlisted the support of the state's attorney general, Jim Hogg, to ensure that payment of the residue of the land due to the contractors would be withheld until all defects had been repaired to his satisfaction.69 Taylor, desperate to conclude the contract, offered to have independent experts inspect the building and promised to correct any faults that were pointed out to him. The Capitol Board accordingly secured the services of Washington architect Edward Miller, who examined the structure and reported a number of problems of a fairly minor nature. By December 1888 these faults had been rectified to Miller's satisfaction, and on December 8, on his recommendation, the state unanimously agreed to accept the building, thus closing the first troubled chapter in the history of the Texas State Capitol.

What was the main significance of the Capitol boycott of 1886 and the consequent introduction of strikebreakers from Aberdeen? The importation of the Scottish tradesmen did not hinder the completion of the building; indeed their skills, together with the continuing labor of numerous convicts, perhaps expedited its construction. Nor did the ill-feeling generated have any permanent impact on the continuing flow of granite tradesmen from northeast Scotland to the United States. The American Granite Cutters' Union certainly used the incident to make a stand against unfair competition from convict and nonunion labor. But its real significance lay in the way in which (through the ensuing court case and congressional enquiry) the dispute focused national attention on the one-year-old Contract Labor Law and exposed the inadequacy of that legislation.70 The Capitol boycott provided the first test for legislation that, despite being rewritten by Congress on at least six occasions between 1887 and 1907, remained founded on a misconception and therefore never succeeded in its aim of preventing the immigration of undesirable aliens.