Sun Yat-sen

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/11/20

This is a Chinese name; the family name is Sun.

Sun Yat-sen 孫中山 / 孫逸仙

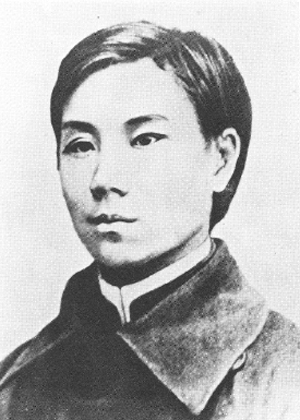

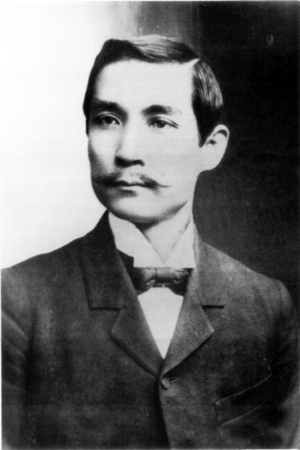

Sun Yat-Sen in 1900

Provisional President of the Republic of China

In office: 1 January 1912 – 10 March 1912

Vice President: Li Yuanhong

Preceded by: Puyi (Emperor of China)

Succeeded by Yuan Shikai

Premier of the Kuomintang

In office: 10 October 1919 – 12 March 1925

Preceded by: Position established

Succeeded by Zhang Renjie (as chairman)

Personal details

Born: Sun Wen (孫文), 12 November 1866, Cuiheng, Guangdong, Qing Dynasty

Died: 12 March 1925 (aged 58), Beijing, Republic of China

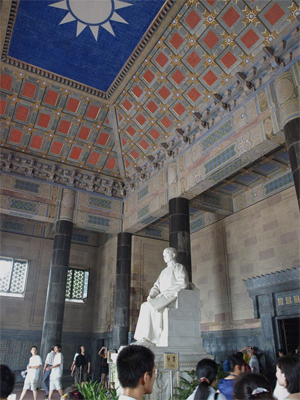

Resting place: Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum, Nanjing, Jiangsu, People's Republic of China

Political party: Kuomintang

Other political affiliations: Chinese Revolutionary Party

Spouse(s): Lu Muzhen (m. 1885; div. 1915); Kaoru Otsuki (m. 1903–1906); Soong Ching-ling (m. 1915–1925)

Domestic partner: Chen Cuifen (concubine) (1892–1925); Haru Asada (concubine)(1897–1902)

Children: Sun Fo; Sun Yan; Sun Wan; Fumiko Miyagawa

Mother: Madame Yang

Father: Sun Dacheng

Alma mater: Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese (MD)

Occupation: Philosopher, physician, politician

Military service

Allegiance: Republic of China

Branch/service: Republic of China Army

Years of service: 1917–1925

Rank: Grand Marshal

Battles/wars: Xinhai Revolution; Second Revolution; Constitutional Protection Movement; Guangdong-Guangxi War; Warlord Era

Sun Yat-sen (/ˈsʌn ˌjætˈsɛn/; born Sun Wen; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)[1][2] was a Chinese philosopher, physician, and politician, who served as the provisional first president of the Republic of China and the first leader of the Kuomintang (Nationalist Party of China). He is referred as the "Father of the Nation" in the Republic of China for his instrumental role in the overthrow of the Qing dynasty during the Xinhai Revolution. Sun is unique among 20th-century Chinese leaders for being widely revered in both mainland China and Taiwan.[3]

Sun is considered to be one of the greatest leaders of modern China, but his political life was one of constant struggle and frequent exile. After the success of the revolution in which Han Chinese regained power after 268 years of living under the Manchu Qing dynasty, he quickly resigned as President of the newly founded Republic of China and relinquished it to Yuan Shikai.

Yuan Shikai (Chinese: 袁世凱; pinyin: Yuán Shìkǎi; 16 September 1859 – 6 June 1916) was a Chinese military and government official who rose to power during the late Qing dynasty. He tried to save the dynasty with a number of modernization projects including bureaucratic, fiscal, judicial, educational, and other reforms, despite playing a key part in the failure of the Hundred Days' Reform. He established the first modern army and a more efficient provincial government in North China in the last years of the Qing dynasty before the abdication of the Xuantong Emperor, the last monarch of the Qing dynasty, in 1912. Through negotiation, he became the first official president of the Republic of China in 1912.

This army and bureaucratic control were the foundation of his autocratic rule as the first formal President of the Republic of China. He was frustrated in a short-lived attempt to restore hereditary monarchy in China, with himself as the Hongxian Emperor (Chinese: 洪憲皇帝). His death shortly after his abdication formalized the fragmentation of the Chinese political system and the end of the Beiyang government as China's central authority.

-- Yuan Shikai, by Wikipedia

He soon went to exile in Japan for safety but returned to found a revolutionary government in the South as a challenge to the warlords who controlled much of the nation. In 1923, he invited representatives of the Communist International to Canton to re-organize his party and formed a brittle alliance with the Chinese Communist Party. He did not live to see his party unify the country under his successor, Chiang Kai-shek in the Northern Expedition. He died in Beijing of gallbladder cancer on 12 March 1925.[4]

Sun's chief legacy is his political philosophy known as the Three Principles of the People: Mínzú (民族主義, Mínzú Zhǔyì) or nationalism (independence from foreign imperialist domination), Mínquán (民權主義, Mínquán Zhǔyì) or "rights of the people" (sometimes translated as "democracy"), and Mínshēng (民生主義, Mínshēng Zhǔyì) or people's livelihood (sometimes translated as "socialism" or "welfare"; he explained the difference between his concept and Karl Marx's concept of socialism in his book[which?]).[5][6][7]

Names

Main article: Names of Sun Yat-sen

Sun was born as Sun Wen (Cantonese: Syūn Màhn; 孫文), and his genealogical name was Sun Deming (Syūn Dāk-mìhng; 孫德明).[1][8] As a child, his pet name was Tai Tseung (Dai-jeuhng; 帝象).[1] Sun's courtesy name was Zaizhi (Jai-jī; 載之), and his baptized name was Rixin (Yaht-sān; 日新).[9] While at school in Hong Kong he got the art name Yat-sen (Chinese: 逸仙; pinyin: Yìxiān).[10] Sūn Zhōngshān (孫中山), the most popular of his Chinese names, is derived from his Japanese name Nakayama Shō (中山樵), the pseudonym given to him by Tōten Miyazaki while in hiding in Japan.[1]

Early years

Birthplace and early life

Sun Wen was born on 12 November 1866 to Sun Dacheng and Madame Yang.[2] His birthplace was the village of Cuiheng, Xiangshan County (now Zhongshan City), Guangdong.[2] He had a cultural background of Hakka[11][12] and Cantonese. His father owned very little land and worked as a tailor in Macau, and as a journeyman and a porter.[13] After finishing primary education, he moved to Honolulu in the Kingdom of Hawaii, where he lived a comfortable life of modest wealth supported by his elder brother Sun Mei.[14][15][16][17]

Education years

At the age of 10, Sun began seeking schooling,[1] and he met childhood friend Lu Haodong.[1] By age 13 in 1878, after receiving a few years of local schooling, Sun went to live with his elder brother, Sun Mei (孫眉) in Honolulu.[1] Sun Mei financed Sun Yat-sen's education and would later be a major contributor for the overthrow of the Manchus.[14][15][16][17]

Sun Yat-sen (back row, fifth from left) and his family

During his stay in Honolulu, Sun Yat-sen went to ʻIolani School where he studied English, British history, mathematics, science, and Christianity.[1] While he was originally unable to speak English, Sun Yat-sen quickly picked up the language and received a prize for academic achievement from King David Kalākaua before graduating in 1882.[18] He then attended Oahu College (now known as Punahou School) for one semester.[1][19] In 1883 he was sent home to China as his brother was becoming worried that Sun Yat-sen was beginning to embrace Christianity.[1]

When he returned to China in 1883 at age 17, Sun met up with his childhood friend Lu Haodong again at Beijidian (北極殿), a temple in Cuiheng Village.[1] They saw many villagers worshipping the Beiji (literally North Pole) Emperor-God in the temple, and were dissatisfied with their ancient healing methods.[1] They broke the statue, incurring the wrath of fellow villagers, and escaped to Hong Kong.[1][20][21] While in Hong Kong in 1883 he studied at the Diocesan Boys' School, and from 1884 to 1886 he was at The Government Central School.[22]

In 1886 Sun studied medicine at the Guangzhou Boji Hospital under the Christian missionary John G. Kerr.[1] Ultimately, he earned the license of Christian practice as a medical doctor from the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese (the forerunner of The University of Hong Kong) in 1892.[1][10] Notably, of his class of 12 students, Sun was one of the only two who graduated.[23][24][25]

Religious views and Christian baptism

In the early 1880s, Sun Mei sent his brother to ʻIolani School, which was under the supervision of British Anglicans and directed by an Anglican prelate named Alfred Willis. The language of instruction was English. Although Bishop Willis emphasized that no one was forced to accept Christianity, the students were required to attend chapel on Sunday. At Iolani School, young Sun Wen first came in contact with Christianity. In his work, Schriffin speculated that Christianity was to have a great influence on Sun's whole future political life.[26]

Sun was later baptized in Hong Kong (on 4 May 1884) by Rev. C. R. Hager[27][28][29] an American missionary of the Congregational Church of the United States (ABCFM) to his brother's disdain. The minister would also develop a friendship with Sun.[30][31] Sun attended To Tsai Church (道濟會堂), founded by the London Missionary Society in 1888,[32] while he studied Western Medicine in Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese. Sun pictured a revolution as similar to the salvation mission of the Christian church. His conversion to Christianity was related to his revolutionary ideals and push for advancement.[31]

Transformation into a revolutionary

Four Bandits

Sun (second from left) and his friends the Four Bandits: Yeung Hok-ling (left), Chan Siu-bak (middle), Yau Lit (right), and Guan Jingliang (關景良, standing) at the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese, circa 1888

During the Qing-dynasty rebellion around 1888, Sun was in Hong Kong with a group of revolutionary thinkers who were nicknamed the Four Bandits at the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese.[33] Sun, who had grown increasingly frustrated by the conservative Qing government and its refusal to adopt knowledge from the more technologically advanced Western nations, quit his medical practice in order to devote his time to transforming China.

Furen and Revive China Society

In 1891, Sun met revolutionary friends in Hong Kong including Yeung Ku-wan who was the leader and founder of the Furen Literary Society.[34] The group was spreading the idea of overthrowing the Qing. In 1894, Sun wrote an 8,000 character petition to Qing Viceroy Li Hongzhang presenting his ideas for modernizing China.[35][36][37] He traveled to Tianjin to personally present the petition to Li but was not granted an audience.[38] After this experience, Sun turned irrevocably toward revolution. He left China for Hawaii and founded the Revive China Society, which was committed to revolutionizing China's prosperity. Members were drawn mainly from Chinese expatriates, especially the lower social classes. The same month in 1894 the Furen Literary Society was merged with the Hong Kong chapter of the Revive China Society.[34] Thereafter, Sun became the secretary of the newly merged Revive China society, which Yeung Ku-wan headed as president.[39] They disguised their activities in Hong Kong under the running of a business under the name "Kuen Hang Club"[40]:90 (乾亨行).[41]

First Sino-Japanese War

In 1895, China suffered a serious defeat during the First Sino-Japanese War. There were two types of responses. One group of intellectuals contended that the Manchu Qing government could restore its legitimacy by successfully modernizing.[42] Stressing that overthrowing the Manchu would result in chaos and would lead to China being carved up by imperialists, intellectuals like Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao supported responding with initiatives like the Hundred Days' Reform.[42] In another faction, Sun Yat-sen and others like Zou Rong wanted a revolution to replace the dynastic system with a modern nation-state in the form of a republic.[42] The Hundred Days' reform turned out to be a failure by 1898.[43]

From uprising to exile

First Guangzhou uprising

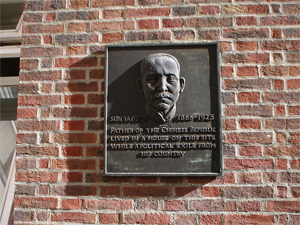

Plaque in London marking the site of a house at 4 Warwick Court, WC1 where Sun Yat-sen lived while in exile

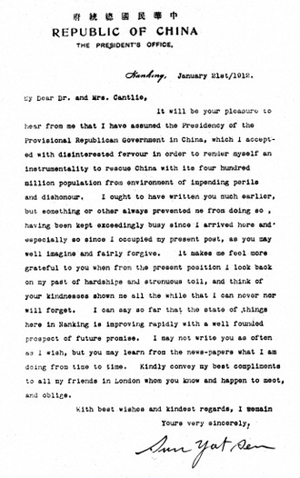

Letter from Sun Yat-sen to James Cantlie announcing to him that he has assumed the Presidency of the Provisional Republican Government of China, dated 21 January 1912

In the second year of the establishment of the Revive China society on 26 October 1895, the group planned and launched the First Guangzhou uprising against the Qing in Guangzhou.[36] Yeung Ku-wan directed the uprising starting from Hong Kong.[39] However, plans were leaked out and more than 70 members, including Lu Haodong, were captured by the Qing government. The uprising was a failure. Sun received financial support mostly from his brother who sold most of his 12,000 acres of ranch and cattle in Hawaii.[14] Additionally, members of his family and relatives of Sun would take refuge at the home of his brother Sun Mei at Kamaole in Kula, Maui.[14][15][16][17][44]

Exile in Japan

Sun Yat-sen spent time living in Japan while in exile. He was supported by the Japanese politician Tōten Miyazaki. Most Japanese who actively worked with Sun were motivated by a pan-Asian fear of encroaching Western imperialism.[45] While in Japan, Sun also met and befriended Mariano Ponce, then a diplomat of the First Philippine Republic.[46] During the Philippine Revolution and the Philippine–American War, Sun helped Ponce procure weapons salvaged from the Imperial Japanese Army and ship the weapons to the Philippines. By helping the Philippine Republic, Sun hoped that the Filipinos would win their independence so that he could use the archipelago as a staging point of another revolution. However, as the war ended in July 1902, America emerged victorious from a bitter 3-year war against the Republic. Therefore, the Filipino dream of independence vanished with Sun's hopes of collaborating with the Philippines in his revolution in China.[47]

Huizhou uprising in China

On 22 October 1900, Sun launched the Huizhou uprising to attack Huizhou and provincial authorities in Guangdong.[48] This came five years after the failed Guangzhou uprising. This time, Sun appealed to the triads for help.[49] This uprising was also a failure. Miyazaki, who participated in the revolt with Sun, wrote an account of this revolutionary effort under the title "33-year dream" (三十三年之夢) in 1902.[50][51]

Further exile

Sun was in exile not only in Japan but also in Europe, the United States, and Canada. He raised money for his revolutionary party and to support uprisings in China. While the events leading up to it are unclear, in 1896 Sun Yat-sen was detained at the Chinese Legation in London, where the Chinese Imperial secret service planned to smuggle him back to China to execute him for his revolutionary actions.[52] He was released after 12 days through the efforts of James Cantlie, The Globe, The Times, and the Foreign Office; leaving Sun a hero in Britain.[note 1] James Cantlie, Sun's former teacher at the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese, maintained a lifelong friendship with Sun and would later write an early biography of Sun.[54]

Heaven and Earth Society, overseas travel

A "Heaven and Earth Society" sect known as Tiandihui had been around for a long time.[55] The group has also been referred to as the "three cooperating organizations" as well as the triads.[55] Sun Yat-sen mainly used this group to leverage his overseas travels to gain further financial and resource support for his revolution.[55] According to the New York Times "Sun Yat-sen left his village in Guangdong, southern China, in 1879 to join a brother in Hawaii. He eventually returned to China and from there moved to the British colony of Hong Kong in 1883. It was there that he received his Western education, his Christian faith and the money for revolution."[56] This is where Sun Yat-sen realized that China needed to change its ways. He knew that the only way that China would change and modernize would be to overthrow the Qing Dynasty.

According to Lee Yun-ping, chairman of the Chinese historical society, Sun needed a certificate to enter the United States at a time when the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 would have otherwise blocked him.[57] However, on Sun's first attempt to enter the US, he was still arrested.[57] He was later bailed out after 17 days.[57] In March 1904, while residing in Kula, Maui, Sun Yat-sen obtained a Certificate of Hawaiian Birth, issued by the Territory of Hawaii, stating that "he was born in the Hawaiian Islands on the 24th day of November, A.D. 1870."[58][59] He renounced it after it served its purpose to circumvent the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.[59] Official files of the United States show that Sun had United States nationality, moved to China with his family at age 4, and returned to Hawaii 10 years later.[60]

Revolution

Tongmenghui

Main article: Tongmenghui

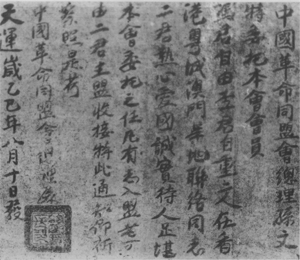

A letter with Sun's seal commencing the Tongmenghui in Hong Kong

In 1904, Sun Yat-sen came about with the goal "to expel the Tatar barbarians (i.e. Manchu), to revive Zhonghua, to establish a Republic, and to distribute land equally among the people" (驅除韃虜, 恢復中華, 創立民國, 平均地權).[61] One of Sun's major legacies was the creation of his political philosophy of the Three Principles of the People. These Principles included the principle of nationalism (minzu, 民族), of democracy (minquan, 民權), and of welfare (minsheng, 民生).[61]

On 20 August 1905, Sun joined forces with revolutionary Chinese students studying in Tokyo, Japan to form the unified group Tongmenghui (United League), which sponsored uprisings in China.[61][62] By 1906 the number of Tongmenghui members reached 963 people.[61]

Malaya support

Main article: Chinese revolutionary activities in Malaya

Interior of the Wan Qing Yuan featuring Sun's items and photos

The Sun Yat-sen Museum in George Town, Penang, Malaysia, where he planned the Xinhai Revolution.[63]

Sun's notability and popularity extends beyond the Greater China region, particularly to Nanyang (Southeast Asia), where a large concentration of overseas Chinese resided in Malaya (Malaysia and Singapore). While in Singapore, he met local Chinese merchants Teo Eng Hock (張永福), Tan Chor Nam (陳楚楠) and Lim Nee Soon (林義順), which mark the commencement of direct support from the Nanyang Chinese. The Singapore chapter of the Tongmenghui was established on 6 April 1906,[64] though some records claim the founding date to be end of 1905.[64] The villa used by Sun was known as Wan Qing Yuan.[64][65] At this point Singapore was the headquarters of the Tongmenghui.[64]

Thus, after founding the Tong Meng Hui, Dr Sun advocated the establishment of The Chong Shing Yit Pao as the alliance's mouthpiece to promote revolutionary ideas. Later, he initiated the establishment of reading clubs across Singapore and Malaysia, in order to disseminate revolutionary ideas among the lower class through public readings of newspaper stories. The United Chinese Library, founded on 8 August 1910, was one such reading club, first set up at leased property on the second floor of the Wan He Salt Traders in North Boat Quay.[66][citation needed]

The first actual United Chinese Library building was built between 1908 and 1911 below Fort Canning – 51 Armenian Street, commenced operations in 1912. The library was set up as a part of the 50 reading rooms by the Chinese Republicans to serve as an information station and liaison point for the revolutionaries. In 1987, the library was moved to its present site at Cantonment Road. But the Armenian Street building is still intact with the plaque at its entrance with Sun Yat Sen's words. With an initial membership of over 400, the library has about 180 members today. Although the United Chinese Library, with 102 years of history, was not the only reading club in Singapore during the time, today it is the only one of its kind remaining.[citation needed]

Siamese support

In 1903, Sun made a secret trip to Bangkok in which he sought funds for his cause in Southeast Asia. His loyal followers published newspapers, providing invaluable support to the dissemination of his revolutionary principles and ideals among Chinese descent in Thailand. In Bangkok, Sun visited Yaowarat Road, in Bangkok's Chinatown. It was on this street that Sun gave a speech claiming that overseas Chinese were "the Mother of the Revolution". He also met local Chinese merchants Seow Houtseng,[67] whose sent financial support to him.

Sun's speech on Yaowarat street was commemorated by the street later being named "Sun Yat Sen Street" or "Soi Sun Yat Sen" (Thai: ซอยซุนยัตเซ็น) in his honour.[68]

Zhennanguan uprising

On 1 December 1907, Sun led the Zhennanguan uprising against the Qing at Friendship Pass, which is the border between Guangxi and Vietnam.[69] The uprising failed after seven days of fighting.[69][70] In 1907 there were a total of four uprisings that failed including Huanggang uprising, Huizhou seven women lake uprising and Qinzhou uprising.[64] In 1908 two more uprisings failed one after another including Qin-lian uprising and Hekou uprising.[64]

Anti-Sun movements

Because of these failures, Sun's leadership was challenged by elements from within the Tongmenghui who wished to remove him as leader. In Tokyo 1907–1908 members from the recently merged Restoration society raised doubts about Sun's credentials.[64] Tao Chengzhang (陶成章) and Zhang Binglin publicly denounced Sun with an open leaflet called "A declaration of Sun Yat-sen's criminal acts by the revolutionaries in Southeast Asia".[64] This was printed and distributed in reformist newspapers like Nanyang Zonghui Bao.[64][71] Their goal was to target Sun as a leader leading a revolt for profiteering gains.[64]

The revolutionaries were polarized and split between pro-Sun and anti-Sun camps.[64] Sun publicly fought off comments about how he had something to gain financially from the revolution.[64] However, by 19 July 1910, the Tongmenghui headquarters had to relocate from Singapore to Penang to reduce the anti-Sun activities.[64] It is also in Penang that Sun and his supporters would launch the first Chinese "daily" newspaper, the Kwong Wah Yit Poh in December 1910.[69]

1911 revolution

Main articles: Wuchang Uprising and Xinhai Revolution

The Revolutionary Army of the Wuchang uprising fighting in the Battle of Yangxia

To sponsor more uprisings, Sun made a personal plea for financial aid at the Penang conference held on 13 November 1910 in Malaya.[72] The leaders launched a major drive for donations across the Malay Peninsula.[72] They raised HK$187,000.[72]

On 27 April 1911, revolutionary Huang Xing led a second Guangzhou uprising known as the Yellow Flower Mound revolt against the Qing. The revolt failed and ended in disaster; the bodies of only 72 revolutionaries were found.[73] The revolutionaries are remembered as martyrs.[73]

On 10 October 1911, a military uprising at Wuchang took place led again by Huang Xing. At the time, Sun had no direct involvement as he was still in exile. Huang was in charge of the revolution that ended over 2000 years of imperial rule in China. When Sun learned of the successful rebellion against the Qing emperor from press reports, he returned to China from the United States accompanied by his closest foreign advisor, the American, "General" Homer Lea. He met Lea in London, where he and Lea unsuccessfully tried to arrange British financing for the new Chinese republic. Sun and Lea then sailed for China, arriving there on 21 December 1911.[74]

The uprising expanded to the Xinhai Revolution also known as the "Chinese Revolution" to overthrow the last Emperor Puyi. After this event, 10 October became known as the commemoration of Double Ten Day.[75]

Republic of China with multiple governments

Provisional government

Main article: Provisional Government of the Republic of China (1912)

"Portrait of Sun Yat-sen" (1921) Li Tiefu Oil on Canvas 93×71.7cm

On 29 December 1911 a meeting of representatives from provinces in Nanking (Nanjing) elected Sun Yat-sen as the "provisional president" (臨時大總統).[76] 1 January 1912 was set as the first day of the First Year of the Republic.[77] Li Yuanhong was made provisional vice-president and Huang Xing became the minister of the army. The new Provisional Government of the Republic of China was created along with the Provisional Constitution of the Republic of China. Sun is credited for the funding of the revolutions and for keeping the spirit of revolution alive, even after a series of failed uprisings. His successful merger of minor revolutionary groups to a single larger party provided a better base for all those who shared the same ideals. A number of things were introduced such as the republic calendar system and new fashion like Zhongshan suits.

Beiyang government

Main article: Beiyang government

Yuan Shikai, who controlled the Beiyang Army, the military of northern China, was promised the position of President of the Republic of China if he could get the Qing court to abdicate.[78] On 12 February 1912 Emperor Puyi did abdicate the throne.[77] Sun stepped down as President, and Yuan became the new provisional president in Beijing on 10 March 1912.[78] The provisional government did not have any military forces of its own. Its control over elements of the New Army that had mutinied was limited and there were still significant forces which still had not declared against the Qing.

Sun Yat-sen sent telegrams to the leaders of all provinces requesting them to elect and to establish the National Assembly of the Republic of China in 1912.[79] In May 1912 the legislative assembly moved from Nanjing to Beijing with its 120 members divided between members of Tongmenghui and a Republican party that supported Yuan Shikai.[80] Many revolutionary members were already alarmed by Yuan's ambitions and the northern based Beiyang government.

Nationalist party and Second Revolution

Tongmenghui member Song Jiaoren quickly tried to control the parliament. He mobilized the old Tongmenghui at the core with the merger of a number of new small parties to form a new political party called the Kuomintang (Chinese nationalist party, commonly abbreviated as "KMT") on 25 August 1912 at Huguang Guild Hall Beijing.[80] The 1912–1913 National assembly election was considered a huge success for the KMT winning 269 of the 596 seats in the lower house and 123 of the 274 senate seats.[78][80] In retaliation the national party leader Song Jiaoren was assassinated, almost certainly by a secret order of Yuan, on 20 March 1913.[78] The Second Revolution took place where Sun and KMT military forces tried to overthrow Yuan's forces of about 80,000 men in an armed conflict in July 1913.[81] The revolt against Yuan was unsuccessful. In August 1913, Sun Yat-sen fled to Japan, where he later enlisted financial aid via politician and industrialist Fusanosuke Kuhara.[82]

Political chaos

In 1915 Yuan Shikai proclaimed the Empire of China (1915–1916) with himself as Emperor of China. Sun took part in the Anti-Monarchy war of the Constitutional Protection Movement, while also supporting bandit leaders like Bai Lang during the Bai Lang Rebellion. This marked the beginning of the Warlord Era. In 1915 Sun wrote to the Second International, a socialist-based organization in Paris, asking it to send a team of specialists to help China set up the world's first socialist republic.[83] At the time there were many theories and proposals of what China could be. In the political mess, both Sun Yat-sen and Xu Shichang were announced as President of the Republic of China.[84]

Path to Northern Expedition

Guangzhou militarist government

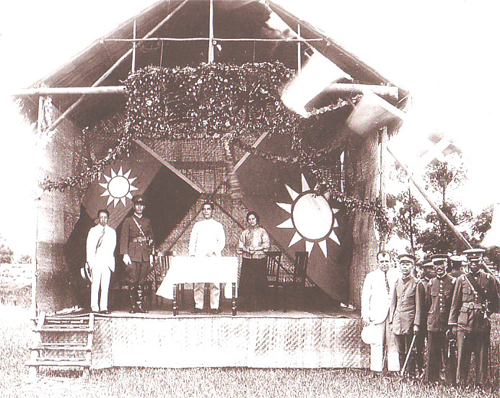

(L-R): Liao Zhongkai, Chiang Kai-shek, Sun Yat-sen and Soong Ching-ling at the founding of the Whampoa Military Academy in 1924

China had become divided among regional military leaders. Sun saw the danger of this and returned to China in 1917 to advocate Chinese reunification. In 1921 he started a self-proclaimed military government in Guangzhou and was elected Grand Marshal.[85] Between 1912 and 1927 three governments had been set up in South China: the Provisional government in Nanjing (1912), the Military government in Guangzhou (1921–1925), and the National government in Guangzhou and later Wuhan (1925–1927).[86] The government in the South was established to rival the Beiyang government in the north.[85] Yuan Shikai had banned the KMT. The short lived Chinese Revolutionary Party was a temporary replacement for the KMT. On 10 October 1919 Sun resurrected the KMT with the new name Chung-kuo Kuomintang, or the "Nationalist Party of China".[80]

KMT–CPC cooperation

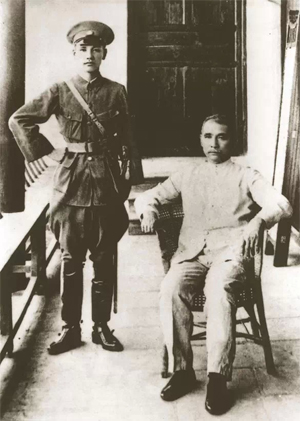

Sun Yat-sen (seated on right) and Chiang Kai-shek

By this time Sun had become convinced that the only hope for a unified China lay in a military conquest from his base in the south, followed by a period of political tutelage that would culminate in the transition to democracy. In order to hasten the conquest of China, he began a policy of active cooperation with the Communist Party of China (CPC). Sun and the Soviet Union's Adolph Joffe signed the Sun-Joffe Manifesto in January 1923.[3] Sun received help from the Comintern for his acceptance of communist members into his KMT. Revolutionary and socialist leader Vladimir Lenin praised Sun and the KMT for their ideology and principles. Lenin praised Sun and his attempts at social reformation, and also congratulated him for fighting foreign Imperialism.[87][88][89] Sun also returned the praise, calling him a "great man", and sent his congratulations on the revolution in Russia.[90]

With the Soviets' help, Sun was able to develop the military power needed for the Northern Expedition against the military at the north. He established the Whampoa Military Academy near Guangzhou with Chiang Kai-shek as the commandant of the National Revolutionary Army (NRA).[91] Other Whampoa leaders include Wang Jingwei and Hu Hanmin as political instructors. This full collaboration was called the First United Front.

Finance concerns

In 1924 Sun appointed his brother-in-law T. V. Soong to set up the first Chinese Central bank called the Canton Central Bank.[92] To establish national capitalism and a banking system was a major objective for the KMT.[93] However Sun was not without some opposition as there was the Canton volunteers corps uprising against him.

Final speeches

Sun (seated, right) and his wife Soong Ching-ling (seated next to him) in Kobe, Japan in 1924

In February 1923 Sun made a presentation to the Students' Union in Hong Kong University and declared that it was the corruption of China and the peace, order and good government of Hong Kong that turned him into a revolutionary.[94][95] This same year, he delivered a speech in which he proclaimed his Three Principles of the People as the foundation of the country and the Five-Yuan Constitution as the guideline for the political system and bureaucracy. Part of the speech was made into the National Anthem of the Republic of China.

On 10 November 1924, Sun traveled north to Tianjin and delivered a speech to suggest a gathering for a "national conference" for the Chinese people. It called for the end of warlord rules and the abolition of all unequal treaties with the Western powers.[96] Two days later, he traveled to Beijing to discuss the future of the country, despite his deteriorating health and the ongoing civil war of the warlords. Among the people he met was the Muslim General Ma Fuxiang, who informed Sun that they would welcome his leadership.[97] On 28 November 1924 Sun traveled to Japan and gave a speech on Pan-Asianism at Kobe, Japan.[98]

Illness and death

For many years, it was popularly believed that Sun died of liver cancer. On 26 January 1925, Sun underwent an exploratory laparotomy at Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH) to investigate a long-term illness. This was performed by the head of the Department of Surgery, Adrian S. Taylor, who stated that the procedure "revealed extensive involvement of the liver by carcinoma" and that Sun only had about ten days to live. Sun was hospitalized and his condition was treated with radium.[99] Sun survived the initial ten-day period and on 18 February, against the advice of doctors, he was transferred to the KMT headquarters and treated with traditional Chinese medicine. This too was unsuccessful and he died on 12 March at the age of 58.[100] Contemporary reports in The New York Times,[100] Time,[101] and the Chinese newspaper Qun Qiang Bao all reported the cause of death as liver cancer, based on Taylor's observation.[102]

Following this the body then was preserved in mineral oil[103] and taken to the Temple of Azure Clouds, a Buddhist shrine in the Western Hills a few miles outside of Beijing.[104] He also left a short political will (總理遺囑) penned by Wang Jingwei, which had a widespread influence in the subsequent development of the Republic of China and Taiwan.[105]

In 1926, construction began on a majestic mausoleum at the foot of Purple Mountain in Nanjing, and this was completed in the spring of 1929. On 1 June 1929, Sun's remains were moved from Beijing and interred in the Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum.

By pure chance, in May 2016, an American pathologist named Rolf F. Barth was visiting the Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall in Guangzhou when he noticed a faded copy of the original autopsy report on display. The autopsy was performed immediately after Sun's death by James Cash, a pathologist at PUMCH. Based on a tissue sample, Cash concluded that the cause of death was an adenocarcinoma in the gallbladder that had metastasized to the liver. In modern China, liver cancer is far more common than gallbladder cancer and although the incidence rates of either in 1925 are not known, if one assumes that they were similar at that time, then the original diagnosis by Taylor was a logical conclusion. From the time of Sun's death until the appearance of Barth's report[99] in the Chinese Journal of Cancer in September 2016 (now known as Cancer Communications[106] since 1 March 2018), the true cause of death of Sun Yat-sen was not reported in any English-language publication. Even in Chinese-language sources, it only appeared in one non-medical online report in 2013.[99][107]