Surya Siddhanta

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 5/15/22

The Surya Siddhanta (IAST: Sūrya Siddhānta; lit. 'Sun Treatise') is a Sanskrit treatise in Indian astronomy from the late 4th-century or early 5th-century CE,[1][2] in fourteen chapters.[3][4][5] The Surya Siddhanta describes rules to calculate the motions of various planets and the moon relative to various constellations, diameters of various planets, and calculates the orbits of various astronomical bodies.[6][7] The text is known from a 15th-century CE palm-leaf manuscript, and several newer manuscripts.[8]

pp. 15–18.

1.5 Surya-Siddhanta

According to the early eleventh-century author Alberuni, the Surya-siddhanta (or some work of the same name) was composed by Lata (Sachau, 1910, p. 153). According to the text itself, it was spoken by an emissary of the sun-god to the Asura (demon) named Maya at the end of Krta-yuga, over two million years ago.

In his translation of the Surya-siddhanta, Ebenezer Burgess notes that some manuscripts seem to connect Maya with the Roman Empire. In the manuscripts without commentary, the sun-god is presented as saying to Maya, "Go therefore to Romaka-city, thine own residence; there, undergoing incarnation as a barbarian, owing to the curse of Brahma, I will impart to thee this science" (Burgess, 1860, p. 3). If Romaka is actually Rome (or a Roman city), this could be interpreted as evidence that the Surya-siddhanta was derived from Greco-Roman astronomy. Of course, it might also be seen as evidence of tampering with the text. [!!!]

The Surya-siddhanta in its present form can be dated firmly as far back as the fifteenth century A.D. There exists a fifteenth-century palm leaf manuscript (No. XXI. N. 8 of the Adyar Library, Madras) of the text of the Surya-siddhanta along with a commentary by Paramesvara (Shukla, 1957, p. 1). We will have occasion to refer to this manuscript in Appendix 8, where we argue that remnants of advanced astronomical knowledge may survive in the Surya-siddhanta.

The astronomy of the Surya-siddhanta presents an epicyclic theory of planetary motion similar to that of Claudius Ptolemy, but it also has many features that may be of Indian origin. It begins with a detailed discussion of the Indian system of world chronology known as the yuga system. This system is based on a catur-yuga of 4,320,000 solar years and a kalpa of one thousand catur-yugas.

In the Surya-siddhanta, these immense periods of time are used as a convenient device for presenting the orbits of the planets. The orbits are described by a series of cycles and epicycles that are combined trigonometrically to reproduce observed planetary motions. Each cyclic period is defined by giving its number of revolutions in a kalpa. Since this is given as a whole number, it follows that all planetary motions will return exactly to their starting point in one kalpa. A similar idea is found in the "great year" of Hellenistic astronomy, and the idea of cyclic time is also prominent in the Indian Puranas and in the Mahabharata.

The Surya-siddhanta describes the periodic motions of the sun, moon, and planets with good accuracy. It also gives the earth-moon distance to within about 11% of the modern value. However, its figures for the distances of the sun and planets are unrealistically small. They are calculated on the assumption that the sun, moon, and planets all move with the same (mean) speed in their orbits, and therefore orbital radii are proportional to orbital periods.

In contrast, Kepler's third law makes the radius proportional to the 2/3 power of the period. For the planets, the proportionality constant in Kepler's law is also much larger than the one used in Surya-siddhanta, which is based on the orbit of the moon.

It is noteworthy that Ptolemy also made the planetary orbits much too small, but he used a different approach. Each geocentric orbit ranges from its perigee (point closest to the earth) to its apogee (furthest point). His idea was that the apogee of each orbit must equal the perigee of the next one out, so that there would be no unused space (see Appendix 4). The result is that the orbit of Saturn is smaller than the earth's orbit as we know it today.

In the Surya-siddhanta, the motion of the planets is said to be controlled by cords of air. The text explains thatForms of Time, of invisible shape, stationed in the zodiac (bhagana), called the conjunction (sighrocca), apsis (mandocca), and node (pata), are the causes of the motion of the planets. The planets, attached to these beings[???] by cords of air, are drawn away by them, with the right and left hand, forward or backward, according to nearness, toward their own place. A wind, moreover, called provector (pravaha) impels them toward their own apices (ucca): being drawn away forward and backward, they proceed by a varying motion (Burgess, 1860, p. 53).

It is interesting to compare this with the cosmology of the Puranas, where we find similar ideas. In the Bhagavata Purana, the rotation of the stars and planets around the polar axis is said to be caused by the daksinavarta wind. This is called the pravaha wind in the Visnu Purana, where a more detailed account is given of the control of planetary motions by cords of air:I have thus described to you, Maitreya, the chariots of the nine planets, all which are fastened to Dhruva by aerial cords. The orbs of all the planets, asterisms, and stars are attached to Dhruva, and travel accordingly in their proper orbits, being kept in their places by their respective bands of air (Wilson, 1980, p. 346).

Chapters 4-6 of the Surya-siddhanta present rules for calculating the times of solar and lunar eclipses. These are based on the same theory of eclipses used in modern astronomy. However, the ascending node of the moon is identified as Rahu, the eclipse demon of the Puranas (see Section 3.4.1). Rahu's counterpart, Ketu, is not mentioned (Burgess, 1860, p. 56).

The Surya-siddhanta contains a chapter on cosmology and geography, in which the earth is portrayed as a self-supporting globe floating in space and surrounded by the planetary orbits. The Puranic Mount Meru is defined as a literal polar axis, passing through the poles, with dwellings of the gods at the northern end and dwellings of the demons at the southern end. In the four quarters, extending south from the north pole to the equator, are four continents with four equatorial cities, as follows (Burgess, 1860, p. 286).TABLE 1.4

Jambudvipa in Surya-siddhanta

Direction / Continent / City

east / Bhadrasva / Yamakoti

south / Bharata / Lanka

west / Ketumala / Romaka

north / Kuru / Siddhapura

These can be compared with the continents (varsas) of the Puranic Jambudvipa (see also Section 2.4.1). The general view of scholars is that the flat Jambudvipa was adapted to the earth globe when Greek astronomy was introduced into India. However, we argue in this work that Jambudvipa of the Puranas was understood as a planisphere model of the earth when the Puranic texts were written. Thus the idea of an earth globe was originally there in the Puranic Jambudvipa. Whether or not this idea was imported from the Greeks is hard to say. The accepted dates for the surviving recensions of the Puranas would allow this, and Ptolemy is known to have authored a work on the planisphere projection, mapping a globe onto a plane.

Pg. 19-46

2. The Islands and Oceans of Bhu-mandala

2.1 Overview of Bhu-Mandala

The main focus of Bhagavata cosmology is on Bhu-mandala -- the "circle of the earth" -- and we will therefore begin by giving an overview of its qualitative and quantitative features. The structure of Bhu-mandala turns out to be primarily astronomical in nature, and we will discuss this in detail in later chapters.astronomy: the study of objects and matter outside the earth's atmosphere and of their physical and chemical properties.

-- Astronomy, by Merriam-Webster

At the same time, its qualitative features refer both to earthly geography and to the world of demigods. Some of the qualitative details appear to be derived from a historical background that begins with the descriptive geography of India and adjoining parts of Asia. In this chapter we will look briefly at this history, but since it is difficult to reconstruct, our main emphasis throughout this book will be on the cosmology of the Bhagavatam as it stands in its present form.

Bhu-mandala is a disk that bisects the sphere of the Brahmanda, the Puranic universe, and it has the same diameter as this sphere. The most noteworthy feature of Bhu-mandala is that it is described in the Bhagavatam and other Puranas in geographical terms. The central region of Bhu-mandala is divided into seven annular or ring-shaped "islands" and "oceans" which alternate, forming a bull's eye pattern. Here the Sanskrit word for island is dvipa, which literally means two waters. This term is appropriate, since most of the dvipas are rings with an ocean on the inside and on the outside.

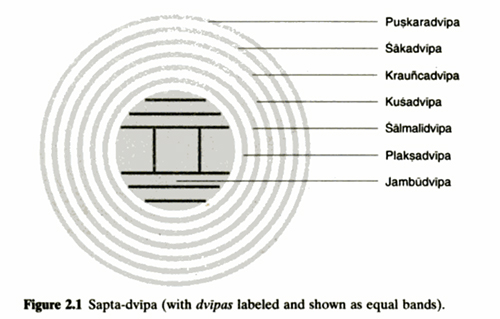

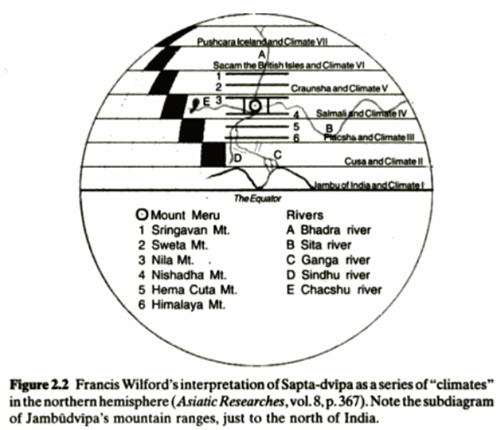

The seven dvipas and oceans are collectively called Sapta-dvipa, and they are surrounded by three larger ring-shaped regions which extend out to the edge of Bhu-mandala. Since they are presented as parts of the earth, many scholars have attempted to identify the seven dvipas with earthly regions or countries. Thus Colonel Wilford, an early Indologist, interpreted the dvipas as seven "climates", or zones of latitude, and he assigned specific countries to them, more or less by imagination (Wilson, 1980, p. 292).

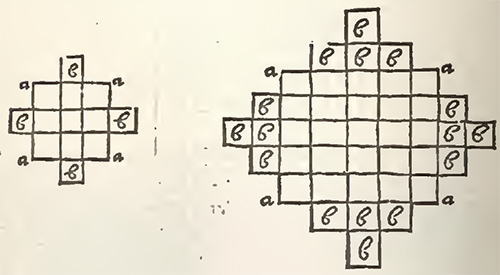

Figure 2.1 Sapta-dvipa (with dvipas labeled and shown as equal bands).

Figure 2.2 Francis Wilford's interpretation of Sapta-dvipa as a series of "climates" in the northern hemisphere (Asiatic Researches, vol. 8, p. 367). Note the subdiagram of Jambudvipa's mountain ranges, just to the north of India.

M. P. Tripathi and D. C. Sircar identify Sakadvipa as the land of the Sakas -- the Greek Scythia -- corresponding to Sakasthana (Seistan in East Iran) and areas to the north of this region. Sircar identifies Kusadvipa with the ancient land of Kush, which he thinks is Ethiopia (Sircar, 1960, pp. 163-64). But Tripathi disagrees and identifies Kusadvipa with the land of the Kushans, powerful people from Central Asia who invaded northern India in the early centuries of our era (Tripathi, 1969, p. 181).

It is possible that the dvipas originally did refer to regions of this earth, but in the existing Puranas they are defined as gigantic circles that do not at all correspond to irregular earthly land masses.[!!!] We will argue that these structures play an essentially astronomical role in Puranic cosmology, although Wilford's climate theory is not completely off the mark.

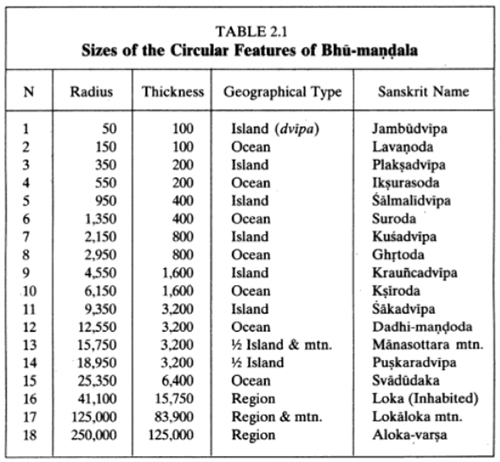

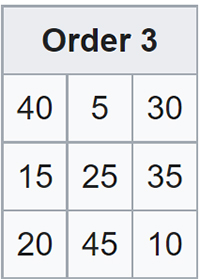

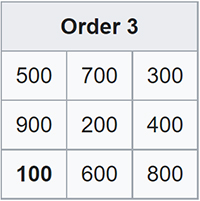

The features of Bhu-mandala are all defined quantitatively using a unit, called the yojana, which is about eight miles in length. The innermost island of Bhu-mandala is Jambudvipa, which has the form of a disk 100,000 yojanas in diameter. Jambudvipa is surrounded by the salt water ocean (Lavanoda), which is a ring 100,000 yojanas across from its inner to its outer edge. This ocean, in turn, is surrounded by the ring-shaped island of Plaksadvipa, which is 200,000 yojanas across. The successive islands and oceans enlarge in as indicated in Table 2.1 (with distances expressed in thousands of yojanas).

In this table, thickness is the distance from the inner radius of a ring-shaped feature to its outer radius. The seven islands and oceans follow the rule that the thickness of an ocean equals the thickness of the island it surrounds and the thickness of that island is twice the thickness of the ocean it surrounds. The circular Jambudvipa is an exception. It surrounds no ocean, and its thickness is its diameter.

The doubling of thicknesses is belied by Figure 2.1, where we show the seven oceans and islands as equal bands. We do this because the oceans and islands do not fit easily in one picture if the doubling rule is followed. For this reason, most traditional diagrams of Bhu-mandala show equal bands.

Table 2.1. Sizes of the Circular Features of Bhu-mandala

Feature 13. called Manasottara Mountain, is a circular mountain range, reminiscent of some of the large craters on the moon. Since it cuts Puskaradvipa in half (see 5.20.30), we listed it in the table as "1/2 Island & mtn." Manasottara Mountain links Bhu-mandala with the orbit of the sun. The axle of the sun's chariot is said to rest at one end on Mount Meru in the center of Bhu-mandala. On the other end, it is supported by a wheel that rolls continuously on the circular track of Manasottara Mountain.[???] As we will see, this solar chariot plays a key role in the astronomical interpretation of Bhu-mandala.

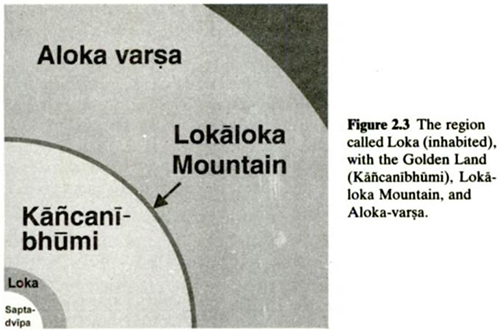

Figure 2.3 The region called Loka (inhabited), with the Golden Land (Kancanibhumi), Lokaloka Mountain, and Aloka-varsa.

The Inhabited Region (Loka) is an exception to the rule of doubling that applies to Sapta-dvipa. Its width is defined in the Bhagavatam verse 5.20.35 to be equal to the radius of Manasottara Mountain, and this is somewhat more than twice the thickness of Svadudaka, the ring that it immediately surrounds. The next ring, called the Golden Land (Kancanibhumi), is assigned a thickness that brings its outer radius to exactly half the radius of Bhu-mandala. This is a bit over twice the radius of Loka. Thus the table of distances is generated (roughly) by doubling, but this doubling is carried out in different ways in different parts of the table.

We note that "Loka" means an inhabited area. In contrast, the Bhagavatam states that the Golden Land is uninhabited. The fifteenth-century commentator, Sridhara Swami, clarifies the dimensions of these two regions as follows. He says that the distance from Manasottara to Meru equals the width of the inhabited earth beyond Svadudaka, and it is 1-1/2 koti and 7-1/2 lakhs (15,750,000) of yojanas. Beyond this is another, golden land measuring eight koti; and thirty-nine lakhs (83,900,000) of yojanas. This reading gives the figures listed in our table. (Here koti and lakh are commonly used terms in Sanskrit designating ten million and one hundred thousand, respectively.)

There is one other circular mountain in addition to Manasottara. This is Lokaloka Mountain, with a radius of 125,000 thousand yojanas (see 5.20.38). This circle divides the illuminated region of Bhu-mandala from the dark, uninhabited region, called Alok-varsa, which extends from Lokaloka to the shell of the Brahmanda.

2.2 THE NOMENCLATURE OF SEVEN DVIPAS

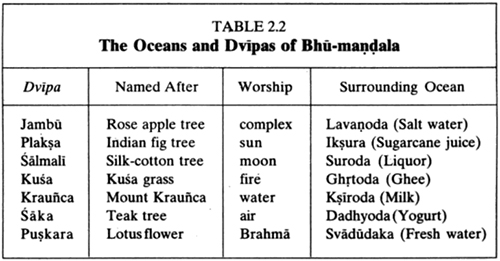

In addition to their bare dimensions, the dvipas are vividly described as populated geographical regions. With one exception, each dvipa is named after a prominent plant said to grow there. The "oceans" are named after various liquids, such as salt water, sugarcane juice, and liquor. The inhabitants of the dvipas are described, and they are said to worship the Supreme God in the form of various demigods. This information is summed up in the following table. In the third column, the terms fire, water, and air refer to the demigods presiding over these elements.

Table 2.2. The Oceans and Dvipas of Bhu-mandala

The five dvipas from Plaksadvipa to Sakadvipa follow a simple pattern, and each is described in a few lines in the Bhagavatam. Each of these dvipas is divided into seven regions called varsas, with seven mountains and seven rivers. Each varsa is ruled by a grandson of Maharaja Priyavrata, a famous personality who is said to have created a second sun by following 180° behind the sun on a brilliantly glowing chariot. The oceans are said to have been ruts, created by his chariot wheels.

According to the table, Kusadvipa is named after a kind of grass. It is noteworthy that a person performing a Vedic fire sacrifice will traditionally sit on a mat made of kusa grass and offer ghee into the fire. Therefore it may be no coincidence that fire is worshiped in Kusadvipa, which is surrounded by the Ghee Ocean.

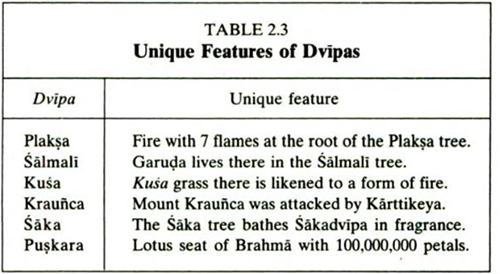

In addition to its geography, founding kings, and peoples, each of the dvipas surrounding Jambudvipa is described as having a particular, unusual feature. These are listed as follows:

Table 2.3. Unique Features of Dvipas

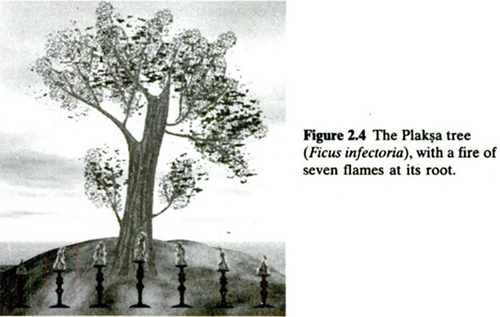

Figure 2.4. The Plaksa tree (Ficus infectoria), with a fire of seven flames at its root.

These picturesque accounts of the islands and oceans of Bhu-mandala have sometimes invoked ridicule, as when Lord Macaulay disparaged seas of treacle in his "Minute on Indian Education" (Macaulay, 1952, p. 723). Certainly, this is not geography in the familiar European sense of the term. However, as we will see later on, the geography of Bhu-mandala encodes a combination of astronomical and geographical maps which is both rational and scientific.[???] It appears that the elements of Bhu-mandala geography have either been introduced or adapted to convey a number of meaningful messages, some of which may still remain obscure. This process may be linked to the historical development of Puranic cosmology, and we now turn to this topic.

2.3 HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF BHU-MANDALA FEATURES

If we survey traditional Sanskrit cosmological texts, we find a number of variations in the nomenclature and layout of the geography of Bhu-mandala. Followers of the Puranas traditionally say that such variations pertain to different kalpas, or periods of creation, but modern scholars tend to see them in historical terms. In this section, we will carry out a comparative study of texts to see what we can learn about the historical development of cosmological ideas.1 [The references used in this study are: Bhagavata P. Bhaktivedanta, 1982; Visnu P. Wilson, 1980; Kurma P. Tagare, 1981; Vayu P. Tagare, 1987; Siva P., 1990; Narosimha P., Jena, 1987: Narada P., Tagare, 1980; Markandeya P., Pargiter, 1981; Vamana P., Mukhopadhyaya, 1968; Siddhanta-siromani, Wilkinson, 1861: Varaha P., Bhattacharya, 1981; Matsya P., Taluqdar, 1916; Mahabharata, Ganguli, 1970; Padma P., Deshpande, 1988: Ramayana, Shastri, 1976.]

Our main conclusion from the study is that the cosmology of the Bhagavatam is unified and well organized, in contrast to many other Puranas (and related texts) that present cosmology in an incomplete or inconsistent way. We seem to see a historical process of imperfect preservation, rather than one of creative development. Unfortunately, the creative phase of Puranic cosmology largely remains hidden, at least as far this study is concerned.

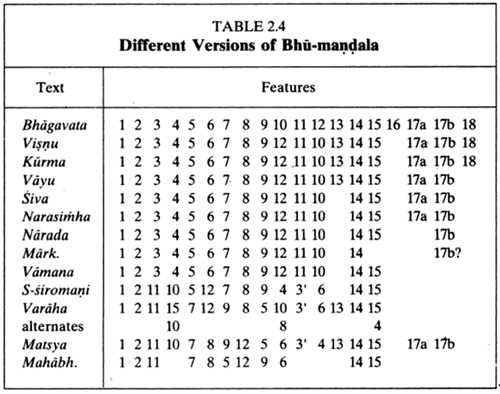

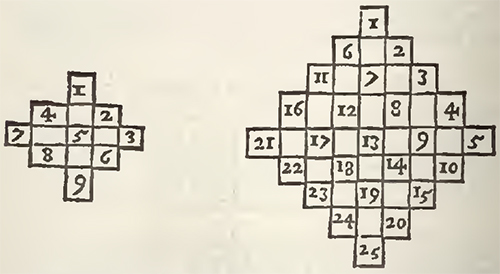

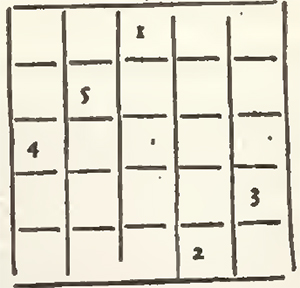

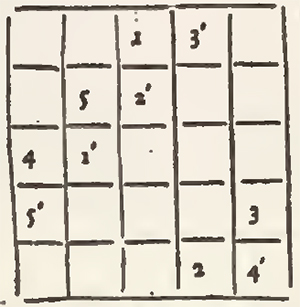

The Puranas largely agree on the names applied to the features of Bhu-mandala, but they may permute them, and some Puranas omit features present in others. Table 2.4 summarizes the situation found in eleven readily available Puranas, in the Mahabharata, and in the Jyotisa text, Siddhanta-siromani. In this table, the feature numbers from Table 2.1 (p. 22) are used to indicate the sequence of Bhu-mandala features listed in each text. The features run from Jambudvipa (1) in the center, out to the outermost feature mentioned. (Number 17a stands for the Golden Land, Kancanibhumi, which in Table 2.1 was combined with feature 17b, the Lokaloka Mountain.)

Table 2.4 Different Versions of Bhu-mandala.

Several observations can be made here. First of all, the Siddhanta-siromani, the Matsya and Varaha Puranas, and the Mahabharata differ as a group from the other Puranas in the table. In the first three of these texts, Plaksadvipa (3) is replaced by Gomedadvipa (3') and switched with Sakadvipa (11).

In the Mahabharata, Plaksadvipa is missing, even though Sanjaya, the narrator, says he will describe seven islands (Ganguli, vol. V, p. 24). Only six islands are mentioned (respectively 1, 11, 7, 5, 9, 14), as well as five oceans (respectively 2, 8, 12, 6, 15). The relationship between the islands and oceans is not indicated, and we have therefore arranged them in the table (preserving order) so as to line up as much as possible with the Matsya Purana. The good matches indicate a strong relationship between the arrangement given in the Mahabharata and the one given in this Purana.

In the Puranas, the seven dvipas and oceans of Bhu-mandala are alternating concentric rings, and their sizes are generally given by the doubling rule of Table 2.1 (p. 22). But in the Mahabharata, it is not clear that dvipas are intended to be concentric rings. Dvipas are said to be surrounded by oceans, but oceans are not said to be surrounded by dvipas. The dvipas in the Mahabharata are said to double as one goes north, but no mention is made of their extent in other directions. Doubling is applied even more extensively in the Mahabharata than in the Puranas, since various mountains are also said to double in size as one goes north (Ganguli, vol. V, pp. 26-27).

Since the Mahabharata is generally dated before the Puranas, one might suppose that its cosmography is ancestral to Puranic cosmography. This is possible. But the cosmography of the Mahabharata is incomplete and unsystematic, and if it does represent an ancestral system, it presents only a fragment of that system -- whatever it may have been.

This naturally leads to the thought that the text of the Mahabharata has become corrupt, and this idea is not new. For example, in his Mahabharatatatparyanirnaya, verses 2.3-4, the thirteenth-century philosopher and religious teacher, Madhavacarya, stated thatIn some places (of the Mahabharata) verses have been interpolated [inserting something of a different nature into something else] and in others verses have been omitted. In some places, the verses have been transposed and in others, different readings have been given out of ignorance or otherwise.

Though the works are really indestructible, they must be deemed to be mostly altered. Mostly all of them have disappeared and not even one crore [ten million] (out of several crores of slokos) now exists (Resnick, 1999).

Many Puranas also present cosmography in an inconsistent fashion. For example, the Varaha Purana mentions duplicate names for three of the oceans. (These are indicated by stacking one alternative above the other in the table.) The Padma Purana contains a nearly verbatim copy of cosmological material from the Mahabharata -- with the interlocutors Sanjaya and Dhrtarastra being replaced by the Puranic narrator, Suta, and a group of sages. But in another place, it gives a different list following the pattern of the Bhagavatam. Thus the Padma Purana contains a mixture of material from different works.[!!!]

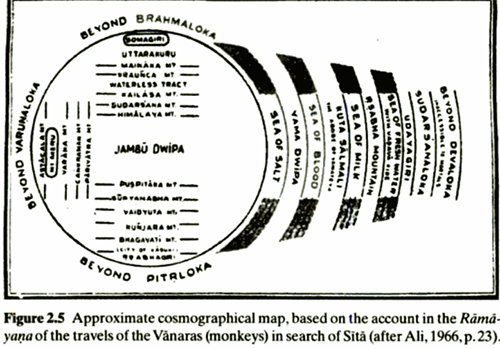

Figure 2.5 Approximate cosmographical map, based on the account in the Ramayana of the travels of the Vanaras (monkeys) in search of Sita (after Ali, 1966, p. 23).

The Ramayana does not mention doubling, and its earth, bounded by dark, inaccessible regions, does not seem to have a succession of alternating oceans and islands. The center is India, and Mount Meru is placed to the west rather than to the north. On the east there is an island of Yava, which might be Java. There is also a Milk Ocean (Ksiroda) and a fresh water sea (Jalada). The Salmali tree of Garuda is located in the east, and the Kraunca mountain is placed in the Himalayas to the north. Apart from this, there is little to remind us of the Puranic Bhu-mandala.

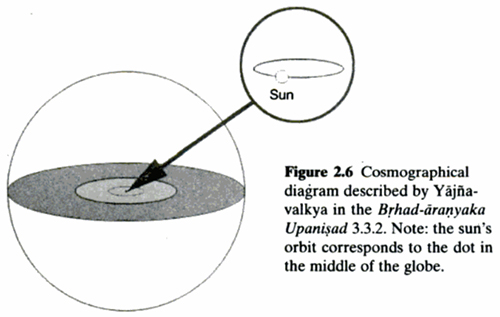

Although the Ramayana may seem to represent an earlier stage in the development of the cosmology, there are earlier references to oceans and land areas that surround one another and double in size from one to the next. For example, the Brhad-aranyaka Upanisad states that "This world is thirty-two times the space crossed by the sun's chariot in a day. The earth twice as that, surrounds it. Surrounding that earth is the ocean twice as large. Then, in between, there is the space as fine as a razor's edge, or as subtle as the wing of a fly" (Sivananda, 1985, p. 294). The Upanisads are generally thought to be much earlier than the Ramayana, but this description is reminiscent of the Puranas, which are held to be later. The reference to the sun's motion suggests that the "earth" and the "ocean" must be extremely large, and this is also seen in the Puranas. The "space as fine as a razor's edge" has been described as a minute opening between the two hemispherical shells of the Brahmanda through which souls may pass.[!!!]

Figure 2.6 Cosmographical diagram described by Yajnavalkya in the Brhad-aranyaka Upanisad 3.3.2. Note: the sun's orbit corresponds to the dot in the middle of the globe.

The first nine Puranas agree on feature names and their order, but some of them list fewer features than others. These Puranas all seem to reflect a single system different from the one in the Matsya Purana. The Bhagavatam, followed by the Visnu Purana, gives the most detailed list of ring-structures in Bhu-mandala. At the same time, some Puranas, such as the Vayu, give much more detailed accounts of the geography of Jambudvipa than the Bhagavatam.

We may ask whether the Puranas with longer lists added some features, or whether the ones with shorter lists dropped some. Our impression on reading the texts is that in many cases, the Puranas refer to the geography of Bhu-mandala in a very cursory way, as though the reader was expected to be already familiar with it.[???] Thus some Puranas neglect to mention all of the feature names.

Since the Bhagavatam differs from all of the other Puranas in its assignment of the Milk (10) and Curd (12) Oceans (Table 2.1, p. 22), it appears that these have been switched for some reason in the Bhagavatam. Likewise, feature 16 (Loka) is listed only in the Bhagavatam, and we can ask whether it is unique to this text. The answer is that indirect evidence suggests that the Bhagavatam's calculations for Loka and the Golden Land were used in other texts as well.

Thus the Bhagavatam makes the radius of Lokaloka one fourth the diameter of the Brahmanda, and the distance from the Sweet Water Ocean to Lokaloka Mountain comes to about ten crores of Yojanas, where a crore is ten million. (The exact figure is 99,650,000 yojanas.) H. H. Wilson finds similar figures in the Siva Tantra. He says, "According to the Siva Tantra, the golden land is ten crores of Yojanas, making, with the seven continents, one fourth of the whole measurement" (Wilson, 1980, p. 294). Thus the Bhagavatam's calculations -- which make use of feature 16 -- appear to be reflected in the Siva Tantra, and they may have a further, unknown background.

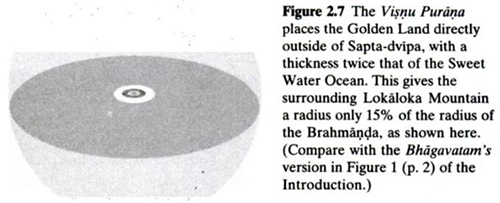

In contrast, the Visnu and Kurma Puranas (which are closest to the Bhagavatam in Table 2.4) both say that the Golden Land has twice the thickness of the Sweet Water Ocean (Svadudaka). This results in a radius of 38,150,000 yojanas for LokaIoka Mountain. All of the Puranas agree that the Brahmanda is 250,000,000 yojanas in radius, and so the radius of Lokaloka Mountain comes to about 15% of the universal radius.

Il is not clear whether this version came before that of the Bhagavatam or after it. But if we assume the former, it is hard to say why the boundary of the Brahmanda was placed so far away from Lokaloka Mountain. The Visnu Purana cannot produce a figure as large as the universal radius by further doubling. For example, doubling thickness again by adding twice the Golden Land would bring one out to only 63,750,000 yojanas. In contrast, the Bhagavatam does generate the universal radius by doubling, and this involves feature 16.

In summary, it does not seem possible at present to trace the geography of Bhu-mandala back to its origins. The existing texts do not explain their calculations, and many of them appear to be corrupt and incomplete. At some point, descriptive geography (perhaps represented by the Ramayana) must have given way to a quasi-geographical system based on circles of immense size. As we will argue later on, the motivation for this was apparently astronomical and involved an analogy between the earth and the sun's path through the heavens. It could have happened at any time in the development of the tradition leading up to the Bhagavatam.

Figure 2.7 The Visnu Purana places the Golden Land directly outside of Sapta-dvipa, with a thickness twice that of the Sweet Water Ocean. This gives the surrounding Lokaloka Mountain a radius only 15% of the radius of the Brahmanda, as shown here. (Compare with the Bhagavatam's version in Figure 1 of the Introduction.

2.4 THE ISLAND OF JAMBUDVIPA

In the Puranas, Jambudvipa is a disk 100,000 yojanas in diameter situated in the center of Bhu-mandala. In the center of Jambudvipa is Mount Meru (or Sumeru) which, in one interpretation, corresponds astronomically to the polar axis of the earth. But even though the center point of Meru may represent the north pole, the cardinal directions east, west, north, and south are defined from it. We will argue later on that Jambudvipa also represents a local map centered on the Pamir mountains, and these cardinal directions are appropriate for this map (see Section 5.1).

On the top of Mount Meru, the cardinal directions and intermediate directions (northeast, southeast, southwest, and northwest) are marked by the eight cities of the Loka-paIas, surrounding the central city of Brahma. It turns out that this arrangement of directional demigods is related to a system of Indian architecture in which a building site on the earth is identified with the ecliptic -- the path of the sun through the heavens. This is discussed below, in Section 2.5. It is significant, because a key interpretation of the earth-mandala is that it represents the ecliptic and the planetary orbits.

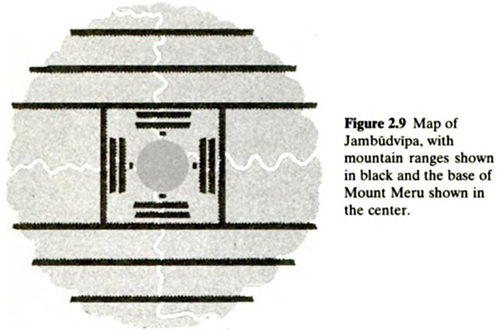

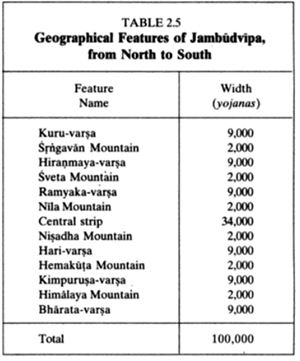

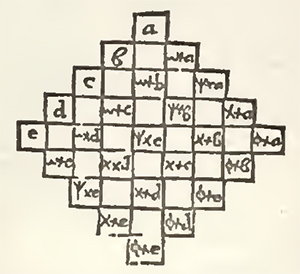

The disk of Jambudvipa is divided in the Puranas into nine varsas, or continents, by a series of mountain ranges, as shown in Figure 2.9. The disk is first of all divided into seven horizontal strips by six ranges that run east-west. In the Bhagavatam, each range is said to be 10,000 yojanas high and 2,000 yojanas wide. The three strips to the north and the three to the south are single varsas, and they are said to extend for 9,000 yojanas in a north-south direction. This leaves 34,000 yojanas for the seventh strip, which consists of three varsas. These features and their north-south dimensions are listed in Table 2.5, going from north to south.

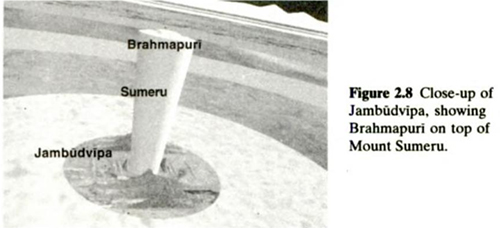

Figure 2.8 Close-up of Jambudvipa, showing Brahmapuri on top of Mount Sumeru.

Figure 2.9 Map of Jambudvipa, with mountain ranges shown in black and the base of Mount Meru shown in the center.

Table 2.5 Geographical Features of Jambudvipa, from North to South

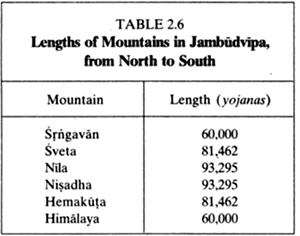

According to 5.16.8, the east-west length of these mountains is supposed to be reduced by a little more than 10% as one goes from mountain to mountain from the center outward. This is roughly true if we extend each mountain range until it meets the circular boundary of Jambudvipa. These lengths appear in Table 2.6.

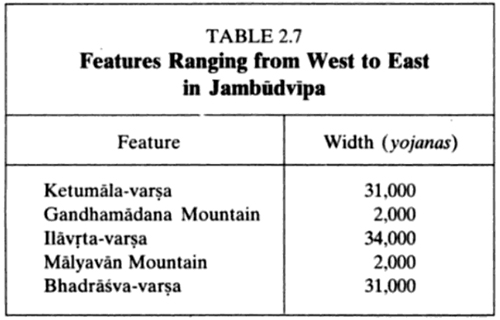

The central strip is divided into three varsas (making nine in total) by two mountain chains that run north-south and extend for 2,000 yojanas. Their north-south length must be 34,000 yojanas. Taking their width in the east-west direction to be 2,000 yojanas, and taking Ilavrta-varsa in the center to be square, the east-west dimensions of these features are in Table 2.7.

Table 2.6 Lengths of Mountains in Jambudvipa, from North to South

Table 2.7 Features Ranging from West to East in Jambudvipa

The inhabitants and topography of Jambudvipa are described in considerable detail. In 5.17.11, Bharata-varsa is singled out as the field of fruitive activities, and the other eight varsas are said to be meant for elevated persons who are enjoying the remainder of their pious credits after returning from the heavenly planets. This suggests that, in one sense, Bharata-varsa is the entire earth and the other eight varsas represent otherworldly, heavenly regions. This is one of the major interpretations of Jambudvipa and Bhu-mandala, and it is discussed in Chapter 6.

Within lIavrta-varsa there are a number of mountains and rivers surrounding Mount Meru. Meru is described in 5.16.7 as being 100,000 yojanas high, with 16,000 yojanas extending beneath the earth and 84,000 yojanas above the earth. It is said to be 32,000 yojanas in diameter at the top and 16,000 yojanas in diameter at the base.

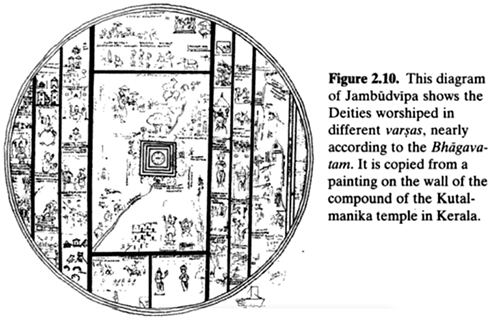

Table 2.10 This diagram of Jambudvipa shows the Deities worshiped in different varsas, nearly accordingly to the Bhagavatam. It is copied from a painting on the wall of the compound of the Kutalmanika temple in Kerala.

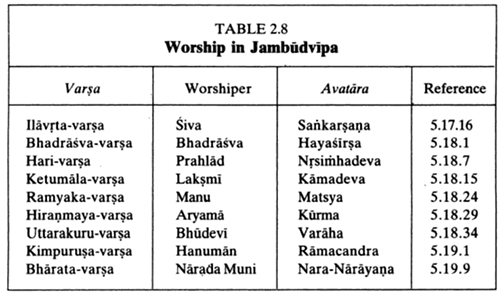

Table 2.8 Worship in Jambudvipa

Mount Meru is therefore in the form of an inverted cone, and it is compared to the pericarp or seed pod of the lotus flower of Bhu-mandala. In the Vayu Purana, Meru is said to be four-sided, with the colors white (east), yellow (south), black (west), and red (north) (Tagare, 1987, pp. 237-38).

In each varsa it is said that an avatara of Visnu is worshiped by a particular famous devotee. In this way, Jambudvipa also plays the role of a divine mandala representing the faith of the Vaisnavas, for whom the Bhagavatam is an important sacred text. The avataras and their worshipers are listed in Table 2.8.

In Bharata-varsa, Nara-narayana is said to be worshiped by Narada Muni in Badarikasrama, a famous site of pilgrimage for thousands of Hindus. This provides a link with a known location in the Himalayas, but we do not have earthly counterparts for the other centers of worship.

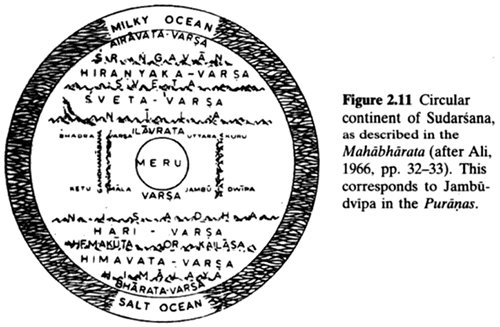

2.4.1 Jambudvipa in the Mahabharata

The Bhisma Parva of the Mahabharata describes a circular island called Sudarsana which is very similar to the Puranic Jambudvipa. The geographical layout of this island is the same as that in Tables 2.5 and 2.7, with the exception that the vertical spacing between the east-west ranges is set at 1,000 yojanas (Ganguli, vol. V, pp. 13-14). However, the height of Mount Meru, situated between the MaIyavan and Gandhamadana mountains, is defined to be 84,000 yojanas, as in the Puranas.

Figure 2.11 Circular continent of Sudarsana, as described in the Mahabharata (after Ali, 1966, pp. 32-33). This corresponds to Jambudvipa in the Puranas

While Sudarsana corresponds to the Puranic Jambudvipa, the term Jambudvipa is used in a different sense in the Mahabharata. Thus, in the Bhisma Parva it is said that "Jamvu Mountain" extends over 18,600 yojanas and the Salt Ocean is twice as big. Sikadvipa is twice as big as Jambudvipa, and another ocean surrounding Sakadvipa is twice the size of that island (Ganguli, vol. V, p. 24). Except for the small size of Jambudvipa, this sounds like Puranic geography as given in the Matsya Purana.

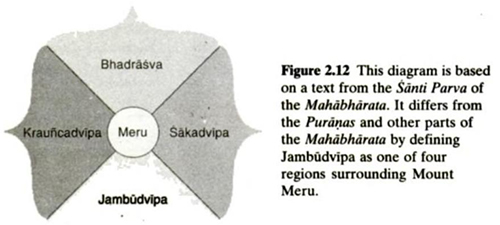

But in the Santi Parva, it is said that King Yudhisthira once ruled Jambudvipa, Krauncadvipa on the west of Meru and equal to Jambudvipa, Sakadvipa on the east of Meru and equal to Krauncadvipa, and Bhadrasva, on the north of Meru and equal to Sakadvipa (Ganguli, vol. VIll, p. 24). This gives us three dvipas and one varsa arranged as equal units around Meru in the cardinal directions. This geographical arrangement is clearly quite different from the one given in the Bhisma Parva.

Then again, if we look back to the Bhisma Parva, we find the statement that "Beside Meru are situated, O lord, these four islands, viz., Bhadraswa, and Kelumala, and Jamvudwipa otherwise called Bharata, and Uttar-Kuru which is the abode of persons who have achieved the merit of righteousness" (Ganguli, vol. V, p. 14). It appears that the Mahabharata is reporting different geographical systems without attempting to systematically reconcile them.

Figure 2.12 This diagram is based on a text from the Santi Parva of the Mahabharata. It differs from the Puranas and other parts of the Mahabharata by defining Jambudvipa as one of four regions surrounding Mount Meru.[/i]

According to Joseph Schwartzberg, [i]an earlier Hindu and Buddhist map of the earth placed four continents in the cardinal directions around Mount Meru, with the continent called Bharata or Jambudvipa to the south (Schwartzberg, 1987, p. 336). The Surya-siddhanta follows this pattern by putting Bhadrasva to the east, Bharata to the south, Ketumala to the west, and Kuru to the north (Burgess, 1860, p. 286).

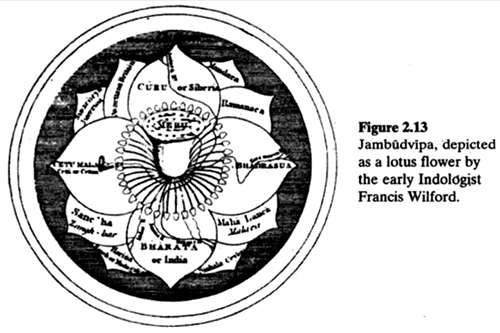

In Figure 2.13, published by the early Indologist Francis Wilford, Jambudvipa is presented as a lotus, with four continents arranged around Meru as listed in the Surya-siddhanta (Wilford, 1805). Note that Kuru-varsa (Curu) is identified as Siberia, so that Meru falls somewhere in the mountainous region north of India. Additional lands near India have been added as extra petals.

Schwartzberg maintains that the original system of four continents was modified over time until it took the form given in Figure 2.9. This may be true, but we may also be dealing with independent traditions making use of the same set of names for islands and continents.

Figure 2.13 Jambudvipa, depicted as a lotus flower by the early Indologist Francis Wilford.

We can distinguish between the two maps of Jambudvipa on purely functional grounds. In relation to actual earthly geography, the four-continent map simply assigns names to lands in the four cardinal directions around Mount Meru (which lies somewhere to the north of India). In contrast, the map in Figure 2.9 gives a more detailed picture of the mountain ranges and valleys in this part of south-central Asia (see Chapter 5). This may explain how these two systems could coexist in the same text.[???]

A basic theme of this study is that models in the Bhagavatam are sometimes used to convey more than one meaning (see the Introduction to Bhagavata Cosmology). Here it appears that the Mahabharata is using geographical terms (such as Sakadvipa) with more than one meaning. One might argue that as alternative meanings accumulated over a long period of time, commentators became tolerant of apparently conflicting meanings, and they tended to resolve conflicts by looking at statements from the standpoint of local context.

2.5 LORDS OF THE DIRECTIONS

Concluding this chapter, we show how an apparently minor detail of Jambudvipa is connected with the astronomy of the ecliptic and with rich astronomical traditions of Indochina. This connection provides data which corroborates the close correlations between Bhu-mandala and modern astronomy [???!!!] that we will discuss in Chapter 4.

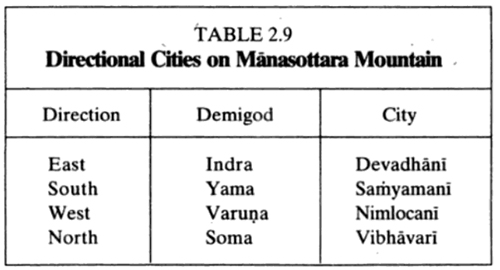

The Bhagavatam verse 5.21.7 describes four cities of the demigods situated on Manasottara mountain in the cardinal directions:

Table 2.9 Directional Cities on Manasottara Mountain.

It turns out that these cities are connected with a larger system of directional demigods, and these in turn are connected with the traditional Indian system of architecture known as Vastu Sastra.

Angkor Wat, a Hindu-Buddhist temple and World Heritage Site, is the largest religious monument in the world. This Cambodian temple deploys the same circles and squares grid architecture as described in Indian Vāstu Śastras.

Vastu shastra (vāstu śāstra - literally "science of architecture") are texts on the traditional Indian system of architecture. These texts describe principles of design, layout, measurements, ground preparation, space arrangement, and spatial geometry. The designs aim to integrate architecture with nature, the relative functions of various parts of the structure, and ancient beliefs utilising geometric patterns (yantra), symmetry, and directional alignments.

Vastu Shastra are the textual part of Vastu Vidya - the broader knowledge about architecture and design theories from ancient India. Vastu Vidya is a collection of ideas and concepts, with or without the support of layout diagrams, that are not rigid. Rather, these ideas and concepts are models for the organisation of space and form within a building or collection of buildings, based on their functions in relation to each other, their usage and the overall fabric of the Vastu. Ancient Vastu Shastra principles include those for the design of Mandir (Hindu temples), and the principles for the design and layout of houses, towns, cities, gardens, roads, water works, shops and other public areas.

In contemporary India, states Chakrabarti, consultants that include "quacks, priests and astrologers" fueled by greed are marketing pseudoscience and superstition in the name of Vastu-sastras. They have little knowledge of what the historic Vastu-sastra texts actually teach, and they frame it in terms of a "religious tradition", rather than ground it in any "architectural theory" therein....

According to Chakrabarti, Vastu Vidya is as old the Vedic period and linked to the ritual architecture. According to Michael W. Meister, the Atharvaveda contains verses with mystic cosmogony which provide a paradigm for cosmic planning, but they did not represent architecture nor a developed practice.

Vastu sastras are stated by some to have roots in pre-1st-century CE literature, but these views suffer from being a matter of interpretation. For example, the mathematical rules and steps for constructing Vedic yajna square for the sacrificial fire are in the Sulba-sutras dated to 4th-century BCE. However, these are ritual artifacts and they are not buildings or temples or broader objects of a lasting architecture. Varahamihira's Brihat Samhita dated to about the sixth century CE is among the earliest known Indian texts with dedicated chapters with principles of architecture. For example, Chapter 53 of the Brihat Samhita is titled "On architecture", and there and elsewhere it discusses elements of vastu sastra such as "planning cities and buildings" and "house structures, orientation, storeys, building balconies" along with other topics....

By 6th century AD, Sanskrit texts for constructing palatial temples were in circulation in India. Vāstu-Śastras include chapters on home construction, town planning, and how efficient villages, towns and kingdoms integrated temples, water bodies and gardens within them to achieve harmony with nature....

The Silpa Prakasa of Odisha, authored by Ramachandra Bhattaraka Kaulachara sometime in ninth or tenth century CE, is another Vāstu Śastra. Silpa Prakasa describes the geometric principles in every aspect of the temple and symbolism such as 16 emotions of human beings carved as 16 types of female figures.... in Saurastra tradition of temple building found in western states of India, the feminine form, expressions and emotions are depicted in 32 types of Nataka-stri[???] compared to 16 types described in Silpa Prakasa. Silpa Prakasa provides brief introduction to 12 types of Hindu temples....

Vāstu Śastra Vidya was ignored, during colonial era construction, for several reasons. These texts were viewed by 19th and early 20th century architects as archaic, the literature was inaccessible being in an ancient language not spoken or read by the architects, and the ancient texts assumed space to be readily available....

Vastu Shastra is a pseudoscience, states Narendra Nayak – the head of Federation of Indian Rationalist Associations. In contemporary India, Vastu consultants "promote superstition in the name of science". Astronomer Jayant Narlikar states Vastu Shastra has rules about integrating architecture with its ambience, but the dictates of Vastu and alleged harm or benefits being marketed has "no logical connection to environment". He gives examples of Vastu consultants claiming the need to align the house to magnetic axis for "overall growth, peace and happiness, or that "parallelogram-shaped sites can lead to quarrels in the family", states Narlikar. This is pseudoscience....

Many Agamas, Puranas and Hindu scriptures include chapters on architecture of temples, homes, villages, towns, fortifications, streets, shop layout, public wells, public bathing, public halls, gardens, river fronts among other things. In some cases, the manuscripts are partially lost, some are available only in Tibetan, Nepalese or South Indian languages, while in others original Sanskrit manuscripts are available in different parts of India.

-- Vastu shastra, by Wikipedia

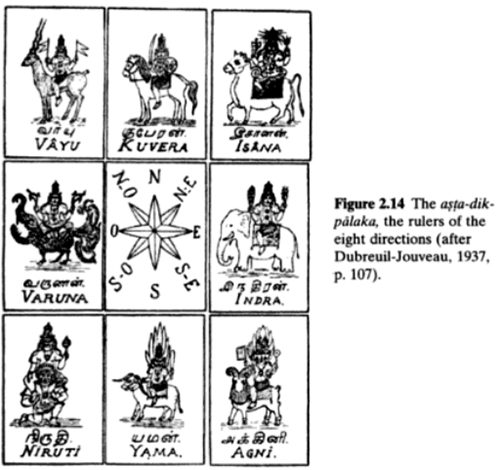

Figure 2.14 The asta-dikpalaka, the rulers of the eight directions (after Dubreuil-Jouveau, 1937, p. 107.

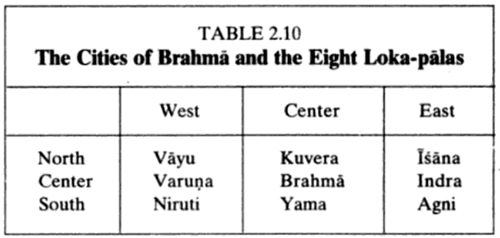

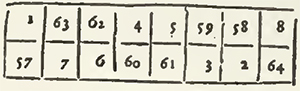

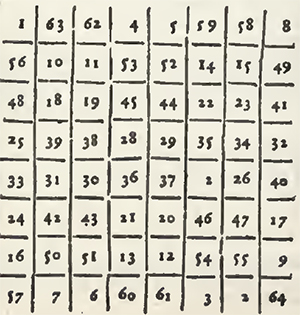

Verse 5.16.29 mentions cities of eight Loka-palas, or lords of the worlds, beginning with lndra. These cities are said to be situated on top of Mount Sumeru, surrounding the city of Lord Brahma (Brahmapuri). The Loka-palas are also known as the Asta-dik-palaka, or eight lords of the directions. They are situated as follows (Dubreuil-Jouveau, 1937, p. 107):

Table 2.10 The Cities of Brahma and the Eight Loka-palas

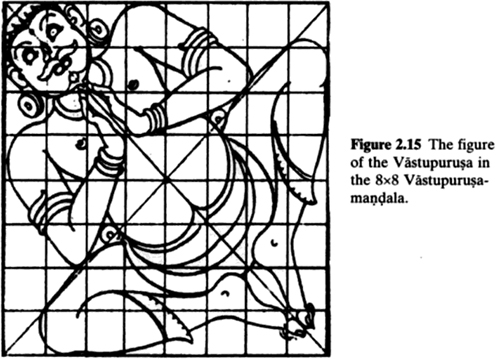

Figure 2.15 The figure of the Vastupurusa in the 8x8 Vastupurusa-mandala

Note that with the exception of Kuvera in the north, the lords of the cardinal directions are the same as the demigods ruling the cardinal points of Minasottara mountain.

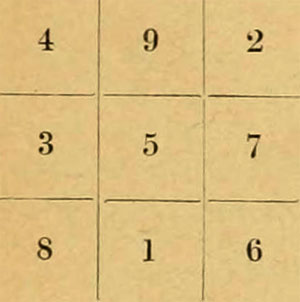

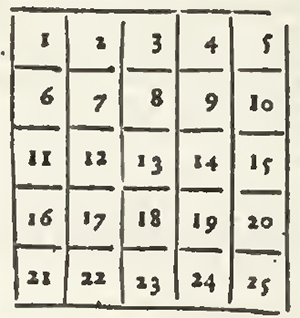

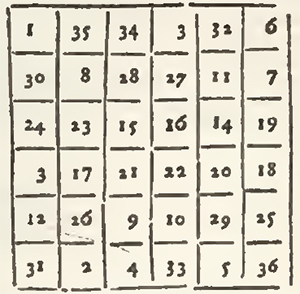

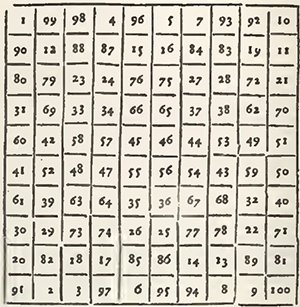

In Vastu Sastra, the layout of a temple or residential house is based on an 8x8 or 9x9 grid of squares, known as the Vastupurusamandala. This grid is associated with the figure of a person called the Vastupurusa, as indicated for the 8x8 grid in the illustration. These grids are always aligned with the cardinal directions.

There are 28 squares in the outer border of the 8x8 grid, and 32 squares in the outer border of the 9x9 grid. These are associated with demigods called Padadevatas. The central 3x3 squares of the 9x9 grid are dedicated to Brahma, and thus the entire grid resembles the top of Mount Sumeru, with Brahmapuri in the center. This is enhanced by the close similarity between the eight Loka-palas and the eight Padadevatas situated at the cardinal and intermediate directions.

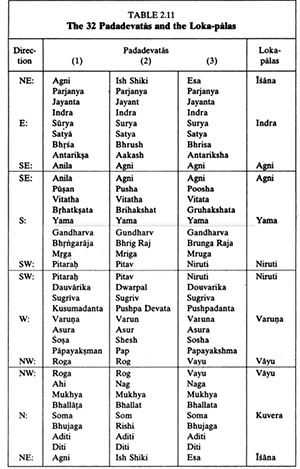

Table 2.11 The 32 Padadevatas and the Loka-palas

For the 9x9 grid, the Padadevatas are listed in the table below. Different sources give small variants in the list of Padadevatas, and in the first three columns we give three lists from (1) (Kramrisch, 1946, p. 32), (2) (Tarkhedkar, 1995, p. 31), and (3) (Sthapati, 1997, p. 205).

The eight Loka-palas are listed for comparison in the fourth column of the table. The demigods are listed in groups of nine for each side of the 9x9 square, and each corner demigod therefore comes at the end of one list and the beginning of the next one. The corner demigods should be compared with the Loka-palas for the intermediate directions, and the demigods in the center squares of the sides should be compared with the Loka-palas for the cardinal directions. The similarity is close enough to indicate a strong connection between the Vastu Sastras and the Puranic lords of the directions. Note that the Padadevata for the center of the northern side is listed as Soma. This disagrees with the Loka-pala list, which has Kuvera, but it agrees with 5.21.7.

There is a connection between the Vastupurusamandala and the ecliptic. The ecliptic is the path of the sun against the background of stars, and in Indian astronomy it is marked by 27 or 28 constellations called naksatras. The Vistupurusamandala, which is situated on the earth, is linked with the ecliptic in the heavens by identifying the four cardinal directions with the solstices and equinoxes and by identifying 28 intermediate directions with the naksatras.

The Indian art historian Stella Kramrisch described this connection as follows for the 9x9 Vastupurusamandala with 32 squares in its border:The 27 and 28 divisions of the Ecliptic become fixed in position like a great, fixed, square dial with the numbers ranging not along the equator, but along the Ecliptic itself. The square, cycle of the Ecliptic, would thus have to be sub-divided into 27 or 28 compartments. Instead of this, the number of Naksatras is augmented to 32, so that each field of the border represents a lunar mansion or Naksatra. In the Vastumandala their number is thus adjusted to the helio-planetary cosmogram of the Prthivimandala. There, the four cardinal points, with reference to the Ecliptic are the equinoxial and solstitial points in the annual cycle. The soIar cycles of the days and years are shown in the Vastumandala together with the lunations, the monthly revolutions of the moon around the earth. The soIar-spatial symbolism is primary and the lunar symbolism is accommodated within the Vastu-diagram (Kramrisch, 1946. p. 31).

According to Kramrisch, the Vastumandala represents a composite of different traditions, and she also mentions a different scheme in which naksatras and their presiding demigod are linked to the cardinal directions (Kramrisch, 1946, p. 34). These demigods are said to rule over positions of entrances to the planned building, and they differ from the 32 Padadevatas.

The ecliptic/Vastumandala link represents a scheme in which part of the earth (where a building is to be erected) is identified with the ecliptic in the sky. There is a similar identification in the Bhagavatam, where the earth-disk, Bhu-mandala, represents the ecliptic plane. It may therefore be significant that the Puranic Loka-palas on Mount Meru are connected with the Vastupurusamandala of Vastu Sastra.[???!!!]

Adrian Snodgrass describes the symbolism of the Vastupurusamandala, and he also relates it to a cosmological account in which the Trayastrimsa Heaven of lndra is situated on Mount Meru, along with 32 directional demigods representing the equinoxes and solstices and the 28 naksatra divisions of the ecliptic. He points out that this symbolism was reflected in the medieval Burmese kingdom of Pegu, in which 32 provinces surrounding the capital city represented the ecliptic and the Loka-palas (Snodgrass, 1990, pp. 210-11 ).

Snodgrass also points out that elaborate astronomical symbolism was built into the temple of Angkor Wat in Cambodia. Thus Angkor Wat "incorporates at least twenty-two significant alignments to equinoctial and solstitial solar risings" (Snodgrass, 1990, p. 216). This implies that Hindu temple builders in Indochina must have been interested in making quantitative astronomical observations, and it may indicate some of the practical astronomy lying behind the Vastumandala concept.

Snodgrass also listed over thirteen different astronomical quantities that were built into the temple of Angkor Wat in multiples of a unit of length called the hat (Sanskrit hasta). For example, "the interior axial lengths of the nine chambers in the central tower are 27 on the east-west axis and 28 on the north-south axis, referring to the 27 or 28 lunar mansions (naksatra) and to the 28 days on which the moon is visible each month" (Snodgrass, 1990, p. 217).

An interesting feature is the latitude of Angkor Wat, which equals the local elevation of the polar axis. This is expressed in the building by several lengths of 13.43 hat, where one hat represents one degree of latitude. This is accurate to 60-90 seconds of arc (Snodgrass, 1990, p. 221). Also, several lengths of 432, 864, 1,296, and 1,728 hat in different parts of the building express the four yugas -- time periods which endure for corresponding numbers of millennia (Snodgrass, 1990, p. 223). (The yuga system is discussed in Section 8.4.)

The hat itself is 0.43454 meters, which is very close to the 0.432 meter hasta discussed in Section 4.5 on the length of the yojana (Snodgrass, 1990, p. 217). This unit, in turn, emerges independently in the study of the correlation between planetary orbits and Bhu-mandala reported in Section 4.4.

-- The Cosmology of the Bhagavata Purana: Mysteries of the Sacred Universe, by Richard L. Thompson [For Sale in Asia Only], 2000

It was composed or revised c. 800 CE from an earlier text also called the Surya Siddhanta.[5] The Surya Siddhanta text is composed of verses made up of two lines, each broken into two halves, or pãds, of eight syllables each.[9]

As described by al-Biruni, the 11th-century Persian scholar and polymath, a text named the Surya Siddhanta was written by one Lāta.[8] The second verse of the first chapter of the Surya Siddhanta attributes the words to an emissary of the solar deity of Hindu mythology, Surya, as recounted to an asura called Maya at the end of Satya Yuga, the first golden age from Hindu texts, around two million years ago.[8][10]

The text asserts, according to Markanday and Srivatsava, that the earth is of a spherical shape.[4] It treats Sun as stationary globe around which earth and other planets orbit. It calculates the earth's diameter to be 8,000 miles (modern: 7,928 miles),[6] the diameter of the moon as 2,400 miles (actual ~2,160)[6] and the distance between the moon and the earth to be 258,000 miles[6] (now known to vary: 221,500–252,700 miles (356,500–406,700 kilometres).[11] The text is known for some of earliest known discussion of sexagesimal fractions and trigonometric functions.[1][2][12]

The Surya Siddhanta is one of several astronomy-related Hindu texts. It represents a functional system that made reasonably accurate predictions.[13][14][15] The text was influential on the solar year computations of the luni-solar Hindu calendar.[16] The text was translated into Arabic and was influential in medieval Islamic geography.[17] The Surya Siddhanta has the largest number of commentators among all the astronomical texts written in India. It includes information about the orbital parameters of the planets, such as the number of revolutions per Mahayuga, the longitudinal changes of the orbits, and also includes supporting evidence and calculation methods.[9]