by Moises Enrique Rodríguez

Copyright © Society for Irish Latin American Studies, 2010

SECTION 4.2: - ’INFORMATION’ and INTELLIGENCE

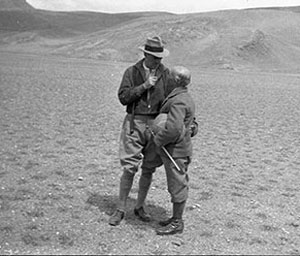

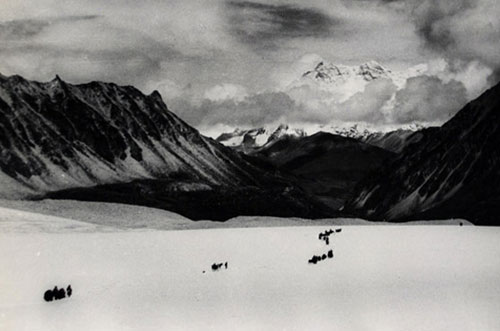

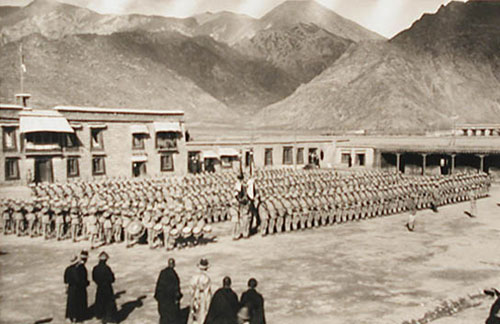

Many aspects of Tibetan politics were little-known to the British prior to the Younghusband Mission, and the systematic gathering of political intelligence became a primary part of the Tibet cadre's role, with paid informants used to gather information. I have previously examined how, during the period 1904-09, the Government of India collected information on Tibetan affairs from Tibet's neighbouring governments (particularly Nepal), and from missionaries on the Eastern Tibetan frontier. Other important news was obtained by the interception of Chinese and Tibetan communications through the Indian telegraph system. In Tibet, cadre officers had informants at all levels of society, and gathered news from European travellers and Indian traders. Intelligence gathering was thus recognised as an integral part of the Tibet cadre's duties.[16]

The National Archives of India show that Trade Agents were provided with a regular Secret Service allowance to pay informants. In 1910, this allowance was greatly increased (from 200 to 1000 rupees per month in the case of Yatung), as 'the local people as well as passing travellers require to be bribed liberally in order to brave the risk of being seen about this Agency by the Chinese'.[17]

Lists of the actual recipients of these funds reveal the wide range of informants used. Those listed naturally include those whose interests coincided with the British -- the Nepalese representative in Gyantse (who received a regular monthly payment of 50 rupees). Indian traders, and Bhutanese officials. O'Connor, building on contacts he had established during the Younghusband Mission, extended this range of informants. Villagers were rewarded with one or two rupees, servants of Lhasa officials and clerks at the Panchen Lama's monastery in Shigatse received 10-50 rupees. The Gyantse Jongpon’s clerk and a Gyantse monk were regular paid informants, and a number of other monks from leading monasteries throughout Lhasa and central Tibet also profited. Perhaps O'Connor's greatest success was in obtaining informants from the Chinese army, and there were also regular payments to a 'Chinese Agent from Lhasa'.[18]

Local agents who proved valuable were taken into regular cadre employment. For example, in 1912, A-chuk Tsering, who later accompanied Bell to Lhasa, was employed as a 'Secret Service Agent' at Ghoom under the District Commissioner Darjeeling, watching the movements of two Japanese studying Tibetan language there. [19]

British travellers also received Secret Service payments. In 1914, the botanist Frank Kingdom-Ward received a token 50 rupee payment for his report on south-eastern Tibet, while new light is shed on the nature of Bailey's travels by entries which reveal he received a substantial payment from Secret Service funds for his journey from Peking to Sadiya in 1911.[20]

Hugh Richardson has claimed that information gathering in Tibet was 'done openly' and that 'there was no clandestine activity or the employment of secret agents which are generally associated with the idea of spying'. But although there are no breakdowns of Secret Service expenditure in official records after 1909, there are private papers from later periods which show that Secret Service funds continued to be used to pay local informants. For example in 1944, Gyantse Trade Agent Mainprice refers to a 'Secret Service' payment of 450 rupees. In addition, the Indian archive indexes confirm that what the Government of India themselves termed 'Secret Agent(s)' were still used to report on Tibet in the 1940s.[21]

Therefore, while British sources claim that, due to the open nature of Tibetan aristocratic society, information was freely obtained in Lhasa, there was nevertheless an ongoing use of 'secret agents' by the British throughout the period of their involvement in Tibet. Once the Tibet positions were established in an intelligence-gathering role there was no further need to articulate this role; the tradition had been established.

There was, however, a reorganisation of intelligence gathering in the 1936-37 period, around the time when Gould and Richardson became respectively Political Officer Sikkim and Trade Agent Gyantse. The relevant archives remain classified, but it is possible to reconstruct the effect of these changes from scattered references to intelligence on the northeastern frontier. [22] Much of the responsibility for intelligence gathering in the region was apparently shifted from the Political Officer Sikkim to the Central Intelligence Officer in Shillong.

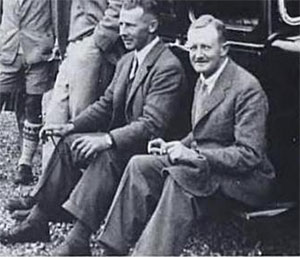

The Central Intelligence Bureau, which had been created by Curzon in April 1904, came under the Home Affairs Department, although it liaised closely with the Political Department; after 1944 all telegrams concerning Tibetan affairs were copied to the Shillong office. This post was occupied during the 1940s by an Irish police officer, Eric Lambert, and after 1946 he was given an assistant based in Kalimpong with particular concern for Tibetan affairs. Lambert's chosen assistant was Lieutenant Lha Tsering, the son of Bell's confidant, A-chuk Tsering. [23]

Lambert's office became an important influence on Tibetan policy in the '40s, but the close links between Lambert and the Political Officer Sikkim suggest they shared similar aims. For example, in September 1944, Lambert recommended an increase in government contributions to Tibetan monasteries, a policy which was enthusiastically followed by the cadre, as will be seen. [24]

The Government of India may not have had a monopoly on clandestine British operations in Tibet. The foreign policy interests of Whitehall and Delhi were not identical, and Whitehall may have used their own agents in Tibet. Certainly Whitehall took over the duty of obtaining British intelligence in Tibet after 1947, with the British High Commission in Delhi suggesting likely avenues of intelligence. [25]

-- Tibet and the British Raj, 1904-47: The Influence of the Indian Political Department Officers, by Alexander McKay

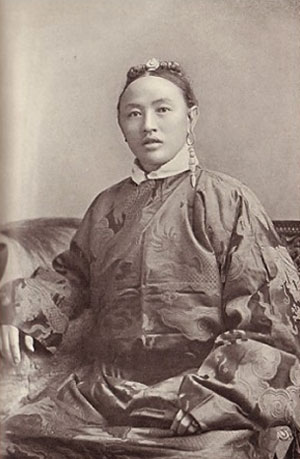

Lambert, Eric (1909-1996), was an Irish historian and former MI-6 intelligence officer who wrote the monumental Voluntarios Británicos e Irlandeses en la Gesta Bolivariana, a major contribution to the little-known history of British and Irish soldiers in the Wars of Independence of Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru.

Born in Dublin, Lambert went to India in 1929, where he worked as a police officer and a colonial administrator until the end of the Raj in 1947. During the Second World War, he remained a civilian but contributed to the war effort against the Japanese in Burma (Myanmar), receiving the temporary Chinese rank of General and the honorary British rank of Major. Upon his return to Europe, Lambert joined MI-6 (or SIS, the British Secret Intelligence Service) for which he undertook several intelligence-gathering missions around the world, including assignments in Latin America and Afghanistan in the 1960s.

In 1962, during a visit to an army base in Ibagué (Colombia), Lambert came across a portrait of Colonel James Rooke, which occupied the place of honour in the officers’ mess. Lambert’s hosts belonged to the Infantry Battalion “Jaime Rooke”, a unit named after a hero of Colombian independence who had died of his wounds at the battle of Pantano de Vargas in 1819. Rooke had been the commander of the “British Legion” of Bolivar’s army and his name is still remembered in Colombia’s history books. The Colombian officers were surprised to learn that Lambert had never heard of Rooke and asked him to research his background. Lambert undertook research at the National Library of Ireland and later published an article on Rooke in a Bogotá newspaper. The Colonel was in fact British in the nineteenth-century sense of the word: he had been born in Dublin of an English father and an Irish mother.

After retiring from MI-6 (or, officially, from the British Foreign Office), Lambert dedicated himself to researching the history of the many British and Irish volunteers who had fought for Bolívar during the Wars of Independence. As well as the three volumes of his monumental Voluntarios, he published Carabobo 1821 (a compilation of accounts in English about that battle) and a series of articles in the Irish Sword. He also contributed to other publications such as the Southern Chronicle and became a leading member of the Military History Society of Ireland.

Unfortunately, Lambert’s Voluntarios was never made available commercially. Only a small number of copies (300-400) were ever printed, and they were distributed to a limited number of libraries mainly in Latin America and Britain and Ireland. The English draft was never published and the work is available only in Spanish.

The book was printed in Caracas (Volume 1 in 1981 and Volumes 2 and 3 in 1993), and led to Lambert being awarded the Order of the Liberator by the Venezuelan government. Publication was delayed partly because some South American historians believed that Lambert was saying that the British and the Irish had liberated their continent from Spanish dominion. Lambert never claimed such a thing, but showed that the foreign volunteers had made an important contribution!

Eric Lambert died on 20 November 1996. In his obituary, John de Courcy Ireland called Lambert’s Voluntarios a model of deep and exacting scholarship. Lambert had no academic training as a historian but his police/intelligence-gathering background made him uniquely qualified for the investigative work required in historical research. He worked from primary sources, purposely ignoring the books of his predecessors in the field: Alfred Hasbrook (whom he considered inaccurate) and Luis Cuervo Marques (of whom he probably had never heard).

Author’s Note

I relied upon Lambert’s books and articles for my own work on the subject but was unable to meet him before he passed away. I was honoured, however, to have met his niece, Laragh Neelin, and the author of the foreword to his book, General Héctor Bencomo of the Venezuelan army. My conversations with them, as well as Neelin’s article in the Irish Sword, are the sources of this biography.

References

- Neelin, Laragh. “Remembering Eric Lambert” in the Irish Sword, 105 (Dublin: Military History Society of Ireland, 2009).

- Lambert, Eric. Voluntarios Británicos e Irlandeses en la Gesta Bolivariana (Caracas: Ministerio de Defensa, 1981 and 1993). 3 vols.