by Wikipedia (France)

Accessed: 1/31/20

Norbhu's contemporary, Rai Bahadur Sonam Wangfel Laden La (1876-1937), was a very different type of individual. A Sikkimese, he was a nephew of Urgyen Gyatso, and worked his way up in the Bengal Police. Displaying a great aptitude for intelligence work, he escorted both the Panchen and Dalai Lamas during their visits to India, in return for which he was given the Tibetan rank of Depon. Laden La also visited Europe, accompanying four Tibetan schoolboys who were sent to Rugby school in 1913. Like Norbhu, he made numerous visits to Lhasa in the 1920s and '30s on behalf of the British. [43]

Laden La became an extremely powerful figure on the frontier, and was active in frontier politics in opposition to the growing power of the Nepali community. [44] Unlike Norbhu, he made many enemies in India and Tibet. The independent observer, William McGovern, accused him of using his position for personal profit, and there is considerable doubt that his own claim to personal popularity in Lhasa bore any close relation to fact. As will be seen in Chapter Four, the Dalai Lama personally intervened to prevent his appointment as Trade Agent Yatung. Despite that, Laden La remained of great value to the Tibet cadre, which, in the light of his failures in other areas, suggests this was because of his intelligence skills. As one officer commented 'Laden La is very full of himself, but is very interesting regarding events and personalities in Lhasa.'[45]

Laden La also differed from Norbhu in that he adopted British dress and social customs, and aspired to a British lifestyle.[46] While he retained the support of the Tibet cadre, he was less successful than Norbhu in cultivating the friendship of the Tibetan leadership, and was not appointed to a Political post. He remained, therefore, by our classification, an intermediary, rather than a member of the Tibet cadre. Thus succeeding local officers of ambition followed the Norbhu model. Ultimately Laden La failed to achieve the desired balance of British and Tibetan understanding and forms of behaviour, and he was not trusted by the Tibetans after his involvement in the events of 1923-24, described in the next chapter.

There was an obvious tension between Norbhu Dhondup and Laden La in addition to that arising from their different life-styles; they represented different local interests and communities. Laden La had connections with Sikkimese aristocracy through his uncle, while Norbhu, though of undistinguished background, was favoured by the Tibetan community with which he identified. These diverging interests have affected subsequent history, with traces of their rivalry remaining among the available oral sources in the Himalayas.

The Rudolphs have shown that competing lineages were common within a particular body of intermediaries in Rajastan.[47] Similarly, British service offered both Norbhu and Laden La the chance to ensure future prosperity for their families, and, ideally, to establish a family administrative lineage. Thus they competed to establish themselves as the most reliable intermediary between British India and Tibet; a contest won by Norbhu, as his promotion to the Tibet cadre indicates. While his son died young, Norbhu's value to the Tibetans may be reflected in the fact that his daughter now works for the Tibetan Government in Dharamsala. Laden La failed to establish a family administrative tradition, but he acquired considerable wealth, and while he died early, his family, like the MacDonalds, established a successful hotel business.

As a nephew of Urgyen Gyatso, Laden La did represent one of the two patterns of service Michael Fisher described.[48] Whereas Palhese and Shabdrung Lama's careers were linked to a British patron, the family tradition of service became the predominant mode among local employees in Tibet: Thus A-chuk Tsering, a Darjeeling Tibetan, and his son Lha Tsering, both served as intelligence agents for the Government of India. Tonyot Tsering, a Sikkimese educated in Kalimpong and Patna Medical College, served as a Sub-Assistant Surgeon in Gyantse, and his son. Tonyot Tsering jnr., served at Gyantse under the British, and from 1949 to 1960 at Lhasa under the Indian Government. Bo Tsering, a Sikkimese Sub-Assistant surgeon at Gyantse and Lhasa from 1914 until c 1950, was closely related to Sonam Tobden Kazi, who succeeded Norbhu Dhondup as Trade Agent Yatung. [49]

Family patterns of loyalty could represent great changes in allegiance, symbolising the process by which the British allied with existing local ruling classes after establishing their place at the top of the political hierarchy. Sonam Tobden Kazi was a great-grandson of the Sikkimese Prime Minister Dewan Namgyal, whose treatment of the Darjeeling Superintendent Dr A. Campbell and botanist J.D. Hooker in 1849 precipitated the eventual British take-over of Sikkim. Whilst Dewan Namgyal had been exiled by the British, Sonam Tobden was to be one of their most valuable employees. [50]....

Tibet's growing military power was closely associated with Tsarong Shape, who rose from humble beginnings to became Commander-in-Chief of the Tibetan Army in 1915. Tsarong had made his name commanding a small force which held off the Chinese army pursuing the Dalai Lama as he fled to exile in India in 1910, after which MacDonald had disguised him as a British mail-runner to enable him to escape to India. Tsarong was clearly an outstanding individual, a powerful figure in Lhasa politics who enjoyed a close relationship with the Dalai Lama. Tsarong was also exceptional in having a great interest in the world outside Tibet, and while British sources emphasise his ties with them, he was clearly equally interested in meeting other foreigners, for he befriended the Japanese travellers to Lhasa in the 1910-20 period, and in later years always met other foreign travellers to Lhasa. [41]

Bailey naturally identified Tsarong as a potential ally. Tsarong, however, lacked either a monastic or aristocratic power base, and his main supporters, army officers who had been trained by the Gyantse Escort Commander or at Quetta Military College, were suspected by conservative Tibetans of having adopted European values.

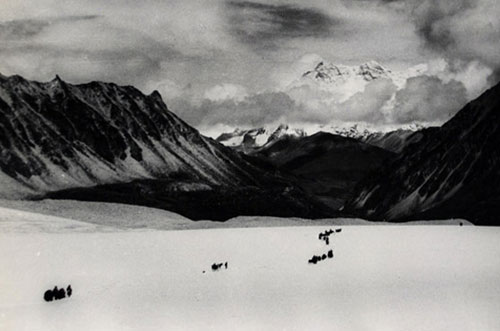

With his government still reluctant to allow its officers access to Lhasa, Bailey faced a problem in establishing close ties with Tsarong. In 1922 he managed, apparently without the support of the Government of India, to arrange for General George Pereira, a former military attache at the British Legation in Peking, to visit Lhasa en route from Peking to India. Although officially described as a ’private traveller', Pereira met Tsarong in Lhasa and sent Bailey detailed reports on Tibetan military forces, recommending that to organise their army 'it is absolutely necessary to send a military advisor to Tsarong'.[42]

In Lhasa, Pereira obviously exerted some influence on the Tibetan Government to follow Bell's earlier recommendation that a police force be established in Lhasa. The day after Pereira left Lhasa the Tibetans asked the Government of India to lend them the services of Laden La to establish and train the Lhasa police.[43] This request gave Bailey the chance to develop ties with Tsarong.

Bailey certainly knew that Whitehall would not sanction posting a British military officer at Lhasa, but Laden La was an experienced police and intelligence officer. He was trusted by the Tibetans, and had recently been in Lhasa with Bell. Just as in 1903, when Curzon had recognised that the distinction between a 'political' and a 'trade' agent was not 'mutually exclusive',[44] Bailey realised Laden La could fill a dual role. Bailey therefore persuaded his government that it was of 'great political importance' that Laden La be sent to Lhasa. So keen were government to use Laden La that he was able to demand promotion to Superintendent as a condition of acceptance, although there were no vacancies at that rank, and a special position had to be created for him. [45]

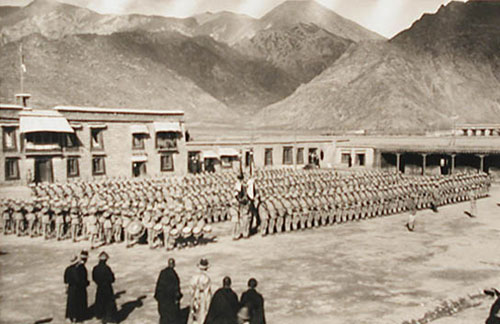

Laden La reached Lhasa in September 1923 and established a 200-man police force. He also established close ties with Tsarong and occupied a central role in subsequent events, the exact nature of which remains unresolved. In May 1924, a fight between police and soldiers ended with Tsarong punishing two soldiers by mutilation, as a result of which one died. Mutilation had been forbidden by the Dalai Lama, and Tsarong’s monastic and aristocratic opponents sought to use this incident to engineer his dismissal. Tsarong’s supporters, including Laden La, sought to preserve his position.[46]

Laden La became involved in what was apparently a half-formed plot to transfer secular power from the Dalai Lama to Tsarong Shape. Had it succeeded, Bailey, who was setting out for Lhasa at this time, could have arrived in Lhasa to be greeted by a new Tibetan Government headed by Tsarong. But the plot was not carried through, and the full implications of these events was not brought out by Bailey's reports at the time. It was several years before somewhat contradictory versions of the story emerged in private correspondence.

Bailey visited Lhasa between 16 July and 16 August 1924. There he spent much of his time in discussions with Tsarong. Bailey's report reveals that he asked Tsarong what would happen if the Dalai Lama died, perhaps a rather curious question given that he was apparently in good health. Tsarong replied that if the Government of India sent troops it would stop any trouble, but Bailey warned him that his government would not interfere in Tibet's internal affairs. Bailey also advised Tsarong to deposit money in India in case he had to flee into exile. [47]

Bailey's departure from Lhasa was the signal for a series of events which greatly reduced British prestige in Tibet. The struggle between the 'conservative' and 'modernising' tendencies in Tibetan society culminated in defeat for those favouring modernisation. Laden La left Lhasa on 9 October 1924 and the police force lost all power. Tsarong conveniently left Tibet on a pilgrimage to India around the same time, and was removed from his post as Army Commander on his return. In Tsarong's absence his young military supporters were down-graded, and a number of other events in this period (such as the closure of the Gyantse school), illustrated the decline in the British position. In the late 1920s there were indications that the Dalai Lama was again turning to China or Russia for support, as the concluding years of Bailey's term in Sikkim saw Anglo-Tibetan relations at a low ebb. [48]

The decline in Anglo-Tibetan relations at this time has been blamed on a number of causes. Ira Klein has emphasised the wider decline in British power in the East at this time. Other observers have blamed the British failure to supply Tibet with further weaponry, or to obtain Chinese agreement to the Simla Convention. But, as the leading studies of this period have all dismissed any suggestion of British involvement in a plot to depose the Dalai Lama, the events involving Laden La have not been seen as significantly affecting Anglo-Tibetan relations, although that would have gone a long way towards explaining the British decline.[49]

Richardson does not refer to the incident at all, but, in connection with Chinese accusations of British support for 'militaristic lay officials who wanted to substitute some form of civil government for the Lama hierarchy' in the 1930s (allegations which may reflect their belated awareness of earlier events), he states that 'to suggest that the British Government would assist such a group -- if it existed -- [sic]...is...inept'.[50]

Lamb, while noting rumours of a conspiracy between Laden La and Tsarong Shape, is content to note that there is 'not a vestige of evidence' for this in the India Office Library records. Goldstein, surveying these events, writes that ’Ladenla[sic] was an Indian official, and it would have been unreasonable to assume he acted without orders or at least official encouragement'; but footnotes this statement with the contradictory remark that 'This is, however, precisely what happened.'[51]

There is no doubt as to Laden La's involvement, although details of his role took some time to emerge. The Gyantse Khenchung, apparently at the Dalai Lama's behest, informed Norbhu Dhondup in 1926 that Laden La had been involved in a plot against the Dalai Lama, allegations which Gyantse school-teacher Frank Ludlow accepted as true. Then when Bailey was on leave in 1927, the Khenchung gave Trade Agent Williamson (who was acting as Political Officer Sikkim during Bailey's absence), a full account of the incident. The Government of India also accepted that Laden La was involved, judging from the National Archives of India restricted file on this matter titled 'Indiscretion of Laden La in associating with Tibetan officers attempting to overthrow the Dalai Lama.'[52]

The Government of India's treatment of Laden La after the incident is instructive. Far from censuring him, they promoted him to Trade Agent in Yatung, but the posting was cancelled after the Dalai Lama, who now deeply mistrusted Laden La, wrote to Norbhu Dhondup objecting to the appointment as 'he [Laden La] is not altogether a steady and straight-forward man and it is not known how he would serve to maintain Anglo-Tibetan amity.'[53]

When Laden La left Lhasa, ostensibly suffering from a nervous breakdown, he took six months' leave, and then resumed his post, continuing to be regarded as a valuable Agent, sent to Lhasa 'on special duty' whenever the need arose. Bailey strongly supported Laden La. He originally argued that the Khenchung's account was 'inconceivable', and when he finally advised his government that Laden La had indeed 'certainly committed a serious indiscretion' stated that he hoped no action would be taken against him: none was.[54]

Has previous scholarship been correct in rejecting any British involvement in this plot? Bailey was one of the outstanding intelligence agents of his time. An illustration of this is that his disguise in Tashkent had been so good that he was hired by the Cheka (the forerunner of the KGB) to find the British agent (Bailey himself), they knew was in the area. There must be considerable doubt that such an officer would be ignorant of the activities of his own key agent in a crucial post. [55]

Circumstantial evidence points to a 'plot'; we cannot necessarily expect empirical evidence. An experienced intelligence operator such as Bailey would naturally conceal evidence of a failed coup attempt if he could. The reporting of events in Tibet was largely controlled by the Political Officer Sikkim, and Bailey apparently took full advantage of his power to restrict government's knowledge of the matter.

Viewed from the perspective we obtain from knowledge of the cadre mentality, the events of this period can be seen to follow a logical sequence which provides a convincing hypothesis to explain the events of the time and the subsequent decline in Anglo-Tibetan relations. Bailey had apparently come to the conclusion that the only way to modernise Tibet to the extent where it would provide a secure northern border for India was by establishing a secular government in Tibet under Tsarong Shape's leadership. Bailey was seriously concerned about the possibility of Bolshevik subversion in Tibet, and the traditional Tibetan leadership cannot have seemed likely to be capable of resisting determined Russian infiltration.[56]

Pereira's reports must have been a significant influence on Bailey; it is clear from the way in which Bailey arranged permission for him to travel freely in areas normally closed to travellers that he had an important role. MacDonald, who was not then in Bailey's confidence, makes the unusual comment on Pereira's travels that, 'Whether his last journey was inspired by motives other than exploration and the desire to be the first European to reach Lhasa from the Chinese side I do not know, nor did he tell me.'[57]

In sending Laden La to encourage Tsarong, Bailey had an agent whose actions he could disown officially if they failed, while rewarding him later for his efforts. There is of course, the possibility that Laden La acted on his own initiative, in the tradition his 'forward' thinking superiors had inculcated in him. But Laden La was not officially attached to the Political Department at this time, and had he been involved in a foreign conspiracy without significant support from higher British officers it is hard to believe he could have escaped dismissal from government service.....

Soon after the Dalai Lama returned to Lhasa, there was a new initiative by the Government of India to overcome Whitehall's objection to a British officer visiting Lhasa. Following a Tibetan request for an officer to arrange the evacuation of the defeated Chinese forces from Lhasa to India, they despatched Laden La to Lhasa.

After ordering Laden La to Gyantse on 24 May 1912, Viceroy Hardinge, apparently waited a week before informing the Secretary of State that Laden La had been sent to Gyantse with orders to prepare to visit Lhasa. Given the slower communications and pace of government at the time, it appears that by waiting until Laden La had reached Gyantse, and then despatching the telegram to London on a Friday, the Government of India intended to present Laden La's arrival in Lhasa to Whitehall as a fait accompli. On Tuesday June 4th, a telegram was sent ordering Laden La to Lhasa. He received the telegram at 9 am on June 5th and departed later that day, accompanied by Norbhu Dhondup. But while the weekend's delay slowed their reaction, Whitehall eventually halted Laden La on June 9th, 40 miles from Lhasa, following a 'clear the line' telegram ordering them to return to Gyantse. [22]....

The Bell Mission to Lhasa in 1920-21 marked a major turning point in the history of the British presence in Tibet. It had the effect of opening the Tibetan capital to regular visits by British officials. Norbhu Dhondup and Laden La subsequently made regular visits to the Tibetan capital, and at least one representative of the Government of India visited Lhasa annually.[28] Ultimately, the Bell Mission paved the way for permanent representation in Lhasa, thus fulfilling the original intention behind Curzon's Tibet policy.[29]...

The two principal intermediaries used on missions to Lhasa were [Sonam Wangfel] Laden La and Norbhu Dhondup. Laden La, as we have seen in the previous chapter, lost the trust of the Tibetans after his actions in 1923-24, and although he was sent to Lhasa again in 1930 by Colonel Weir, the Tibetans remained suspicious of him. He was detained at Chushul ferry and told 'no useful purpose could be served' by his visiting Lhasa. Laden La appealed to Tsarong Shape, who intervened on his behalf in Lhasa, and after two days he was allowed to proceed.[36]

Laden La claimed that his 1930 mission was a success, a claim apparently accepted by his superiors, for he accompanied Colonel Weir to Lhasa later that year and again in 1932.[37] Other sources however, suggest Laden La was still mistrusted by the Tibetans and that he achieved little in Lhasa. Apart from Norbhu Dhondup, whose critiques of Laden La in his letters to Bailey could have been based on personal differences and professional jealousies,[38] there were also regular complaints about Laden La from the now retired David Macdonald.

MacDonald considered that both Laden La and Norbhu Dhondup were responsible for the downturn in Anglo-Tibetan relations, stating that they were working for their own ends, and giving political information to the Tibetans. In addition, Macdonald alleged that Tsarong had been demoted from Shape to Dzasci rank due to the assistance he had given Laden La in getting to Lhasa in 1930. MacDonald's negative view of Norbhu Dhondup was supported by Mr Rosemeyer, the telegraph officer who supervised the Gangtok to Lhasa line, (and himself an Anglo-Indian). He informed Bell that Norbhu was 'not a patch on your former Chief Clerk A-chuk Tse-ring[sic], who was both shrewd and clever'. [39]

But the presence of other foreign agents at Lhasa meant that an intermediaries' career was not without its dangers, Norbhu's life was, he reported, threatened on several occasions by Russian or Chinese agents; in response, he swore 'I...shall not die before I murder at least two, as I have my rifles and pistols...always loaded'.[40]

The extent to which the Sikkim Political Officers relied on the information obtained by these two intermediaries is difficult to assess. Their visits had the advantage that they could be arranged at short notice, while missions by Political Officers involved considerable preparation, and permission from Whitehall. The two men were thus of great value to the British, despite their shortcomings, and considerable reliance was placed upon their knowledge of the culture and people of Tibet. The Political Officers were aware of the difficult position these men held, but exercised their own judgment in assessing the worth of the reports they produced.[41]

-- Tibet and the British Raj, 1904-47: The Influence of the Indian Political Department Officers, by Alexander McKay

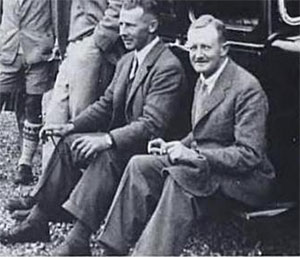

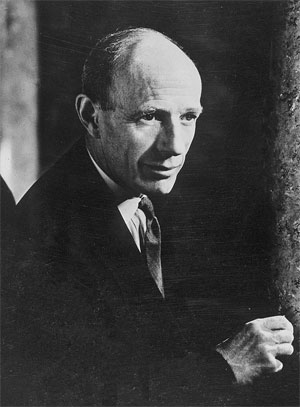

Sonam Wangfel Laden

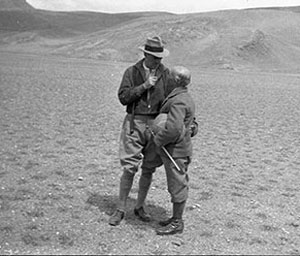

Sonam Wangfel Laden the top left, in the front row Sidkeong Tulku Namgyal, Charles Bell and the 13th Dalai Lama

Birth: 1876, Darjeeling

Death, 1936

Activity: Indianist

Sonam Wangfel Laden (Tibetan : བསོད་ ནམས་ དབང་ འཕེལ་ ལེགས་ ལྡན་ , Wylie: bsod nams dbang 'phel legs Idan) also called Laden La (Tibetan : ལེགས་ ལྡན་ ལགས་ , Wylie: legs Idan lags, 1876 -1936) is an Indian policeman of Tibetan origin.

Biography

Sonam Wangfel Laden was born into a long-standing Tibetan family in the Darjeeling district. He received education from the Jesuits in the region, spoke English fluently as well as several local languages and dialects1.

Between 1894 and 1898, he participated in the writing of a Sanskrit-Tibetan dictionary with Sarat Chandra Das and followed the teachings of Lama Sherab Gyatso from the monastery of Ghoom1.

He joined the Darjeeling police in 1899 and quickly became head of department1.

He participated in a liaison mission in the staff of the British military expedition to Tibet from 1903-19041.

He accompanied the 9th Panchen Lama during his visit of pilgrimage to India (in). He worked to foster good relations between Tibet and British India1.

When the 13th Dalai Lama fled before the Chinese invasion in 1910, he organized his meeting with Lord Minto, the Viceroy of India and stay in Darjeeling1.

In 1912, following the Chinese defeat in Tibet, the viceroy of India (Charles Hardinge) sent him to negotiate a cease-fire and various agreements. On April 15, 1912, he welcomed Alexandra David-Néel who wished to meet the 13th Dalai Lama1.

In 1913, he accompanied the first group of Tibetan boys who had left to study in England at Rugby and on this occasion visited several European countries1. During the First World War, he participated in the recruitment of soldiers and fundraising1.

In 1921, he accompanied Charles Bell, at his request, to Lhassa, during a mission aimed at improving Anglo-Tibetan relations1.

In 1923 1, the 13th Dalai Lama invited as superintendent of Darjeeling police in Lhasa rebuild a civilian police service, due to its decline after the Chinese occupation of Lhasa. He was assisted by the mining engineer trained at Rugby Mondrong Khenrab Kunzag, appointed superintendent2.

In 1929, he was asked to mediate following a deterioration in Tibetan-Nepalese relations1.

He retired in 1931, having received a number of Tibetan and British distinctions, including the Order of the Golden Lion and Commander of the Order of the British Empire. He then became involved in philanthropic and Buddhist works, collaborated in the translation of Padmasambhava's life for The Tibetan Book of the Great Liberation, edited by Walter Evans-Wentz1.

References

1. Joëlle Désiré-Marchand, Alexandra David-Néel: From Paris to Lhassa, from adventure to wisdom , Arthaud, 1997, ( ISBN 2700311434 and 9782700311433 ) , p. 181

2. (in) Tsepon WD Xagabba , Tibet: A Political History. Yale University Press, 1967, p 369, p. 264: " Following the Chinese occupation of Lhasa, the police system had declined and become ineffective. The Dalai Lama invited the Superintendent of Police in Darjeeling, Sonam Laden La, to establish a police department in Lhasa. Laden La, who was of Tibetan extraction, trained several hundred policemen and was appointed Superintendent of Police in Lhasa, with the title of Dzasa. He was assisted by Mondrong Khenrab Kunzag, the Rugby-educated mining engineer."

Bibliography

• (in) Nicholas Rhodes (in) and Deki Rhodes, A Man of the Frontier. SW Laden La (1876-1936). His Life and Times in Darjeeling and Tibet , Library of Numismatic Studies, Kolkata, 2006.

External link

• A hero of the old school [archive], May 23, 2005, The Statesman, India