Tracking Sinhalese Buddhism, Bodh Gaya and Sinhalese, and Allen: British India discovers Buddhism, Excerpt from White Sahibs, Brown Sahibs: Tracking Dharmapala

by Susantha Goonatilake

Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Sri Lanka

New Series, Vol. 54 (2008), pp. 53-136 (84 pages)

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

-- Dharmapala and the Tamil downtrodden, Excerpt from White Sahibs, Brown Sahibs: Tracking Dharmapala, by Susantha Goonatilake

-- Theosophists and Buddhists, Excerpt from White Sahibs, Brown Sahibs: Tracking Dharmapala, by Susantha Goonatilake

-- Tracking Sinhalese Buddhism, Bodh Gaya and Sinhalese, and Allen: British India discovers Buddhism, Excerpt from White Sahibs, Brown Sahibs: Tracking Dharmapala, by Susantha Goonatilake

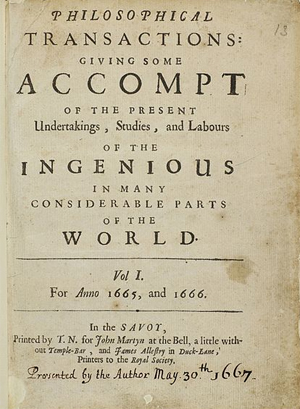

In the 19th century and up to the mid 20th century, there were hardly any formal anthropological writings on Sri Lanka in Western countries. The writings that existed were, apart from Christian tracts and travelers' and administrators' tales a considerable outpouring of texts on Buddhism as in the Pali Text Society and through organizations like the Royal Asiatic Society. Apart from the Christian tracts, these writings were largely sympathetic to the country. The Buddhist texts provided the West for the first time authoritative Buddhist material.

Anthropological writings in Sri Lanka blossomed only since the 1970s at a time when the subject was undergoing a period of deep questioning about its colonial agenda and built-in Eurocentricism. Anthropologists on Sri Lanka like Obeyesekere who emerged at the time did not participate in this questioning of the subject's colonial agenda. The many failings and bias of this anthropology vis-a-vis actual ground fact in Sri Lanka has been explored by the present author in two books and two articles1.

Tracking Sinhalese Buddhism

Since then, several books have appeared again tracking Sinhalese Buddhism, especially actions of Anagarika Dharmapala. These are both in the matter-of-fact genre which was the main staple of writing till the arrival of the distorting lens of recent anthropologists as well as in books that follow in these anthropologists' footsteps. The present article attempts to illustrate the confusion that prevails on the 19th and 20th century Sinhalese Buddhist Renaissance in seven contributions as they describe Buddhism and Sinhalese Buddhist actions. The books are: S. Dhammika, Navel of the Earth: the History and Significance of Bodh Gaya; Charles Allen, The Buddha and the Sahibs; G. Aloysius. Religion as Emancipatory Identity: a Buddhist Movement among Tamils under Colonialism; Alan Trevithick, The revival of Buddhist pilgrimage at Bodh Gaya (1811-1949): Anagarika Dharmapala and the Mahabodhi Temple, H. L. Seneviratne, The work of kings: the new Buddhism in Sri Lanka, Gananath Obeyesekere, Imagining Karma: Ethical Transformation in Amerindian, Buddhist, and Greek Rebirth2. Their focus is on the 19th and early 20th century Buddhists, especially Anagarika Dharmapala and in the case of Obeyesekere, the Buddhist theory that the Sinhalese Renaissance helped unravel to the West. This paper attempts to elicit their underlying messages and their social epistemology.

Sinhalese interactions with India in the 19th and 20th centuries intensify with Sinhalese contributions to the discovery of India's Buddhist past and especially the work of Dharmapala to regain the Buddha's place of Enlightenment, Bodh Gaya.

The most comprehensive historical narrative of Bodh Gaya. especially tracing Sinhalese connections is Navel of the Earth: the History and Significance of Bodh Gaya by Dhammika, an Australian born Buddhist monk who has studied in Sri Lanka's Postgraduate Institute of Pali and Buddhist Studies. It follows the book Buddha Gaya temple: Its history by the Indian, Dipak K. Barua which comes a close second.

Bodh Gaya and Sinhalese

In the 4th century, the Sinhalese King Meghavanna (304- 332 AC) built a special monastery at the Buddha's place of Enlightenment -- the Bodh Gaya Monastery -- which stood for 1,000 years and remained a major University complex parallel to the other two large Buddhist universities of Nalanda and Vikramashila which were built later. The Bodh Gaya Monastery was one of the major educational complexes in the then world and probably the world's first foreign (meaning Sinhalese) funded one.

Dhammika's Navel of the Earth: the History and Significance of Bodh Gaya goes exhaustively into very many historical sources. He gives descriptions of the Sinhalese presence from very early times through inscriptions at the site and descriptions by travellers such as that of Hsuan Tsang the Chinese traveller of the 7th century. The latter has left a vivid description of the Maha Bodhi Monastery. Hsuan Tsang describes this complex as well ornamented having six halls with towers of observation of three stories surrounded by a defence wall of 30 to 40 feet high4. Other inscriptions there mention a royal Sinhalese pilgrim of circa the 8th century; another one in the 10th century refers to a Sinhalese image5. Dhammika notes the excavation by Cunningham in the 19th century which showed the large extent of the Maha Bodhi Monastery. Dhammika observes that, since its founding, the Maha Bodhi Monastery was funded by Sinhalese and dominated by Sinhala monks who came to control the Maha Bodhi Temple itself. Although it had monks from other traditions too, it had become the major centre of Theravada studies in North India6.

Again there is another inscription -- found by Cunningham -- which describes how in the 13th century Sinhalese monks made daily offerings of food, incense and lamps before the Buddha statue at Bodh Gaya. The last epigraphical evidence of Sinhalese monks at the site established around 1262 A.D. is found in an inscription now in the Patna Museum7.

A 12th century inscription describes a donation of members of the Sinhalese order of monks to the Maha Bodhi8. This inscription also indicates that there were a large number of Sinhalese pilgrims there and that their income was important to the Temple9. A Sanskrit poem of the 13th century mentions the Sinhalese monk, Mangala Mahasthavira at Buddha Gaya10. And Dharmavasin, the Tibetan monk of the 13th century mentions the presence of 300 Sinhalese monks officiating at the Bodh Gaya who would not allow any non-Sinhalese monks to sleep in the main courtyard of the Temple11, 12. Dhammika mentions the connections between Bodh Gaya and Burmese Buddhists, especially the repairs to the site undertaken by King Kyanzittha of Pagan (1084-1113). Dhammika recounts that as this was a time of intense relations between Sri Lanka and Burma, the Sinhalese monks resident at Bodh Gaya could have initiated the Burmese contacts with Bodh Gaya13. Illustrating the influence of Sri Lanka on Burma at the time, we should note, is the Myinkba Kubyauk-gyi temple in Pagan built in 1113 AD by Rajakumar. Painted inside are depictions of the Mahavamsa history. the last Sinhalese King painted there is Vijayabahu 1 (1055-1110 A.D) who died shortly before this temple was built14.

An intriguing connection not explored by Dhammika or any of the authorities cited by him is one Cingalaraja of the 15th century as described in 1608 by Taranatha, the historian of the Tibetan tradition 15. Although there are no further details, the name Cingalaraja suggests a Sinhala connection. This is not far-fetched considering that at the time, there were interactions between Buddhists around the region of South-East Asia and North-East India. One Sihalagotta (of the Sinhalese clan) has been ascribed to be a Sinhalese.

Sihalagotta was a general of King Tilokaraja (1448-88) who planted in the monastery Sihalaram [Sinhala monastery] or Mahabodhi Arama (Wat Cet Yod) in Chiangmai in present day Thailand a seedling that was brought from the sacred Bodhi tree at Anuradhapura. Sihalagotta also rebuilt a shrine Rajakuta in which was deposited a sacred relic from Sri Lanka. Saddhatissa has surmised that based on the epithet of "Lanka" mentioned in a Thai text in Pali Atthasalini-atthayojana for a King that the epithet applied to King Tilokaraja16.

With the conquests of North India by Muslims, pilgrimages to Bodh Gaya became difficult and models of the Temple were built in other countries as substitutes for example in the early 13th century in Pagan Burma. In 1472, Dhammaceti, the King of Pegu sent under the leadership of a Sinhalese merchant a large contingent of craftsmen to worship the site and to record plans of the site including its dimensions. It should be noted that this was the same king who reformed the whole Burmese Sangha on Sinhalese pattern after a reordination ceremony of a sangha delegation in 1423 on the Kelani river in Sri Lanka. This is well described in inscriptions and literature17.

Dhammika describes how the Burmese allowed by the British authorities to excavate the Bodh Gaya site in the 19th century, did so in a disorganised manner as British records at the time show. Dhanunika details how the British Archaeology Survey of India went about exploring and restoring the site18.

In describing the actions of Dharmapala at Bodh Gaya, Dhammika quotes the matter of fact descriptions by Dharmapala. Dhammika describes in a straightforward manner the feelings of Dharmapala, as well as of sympathetic Britishers. These include Edwin Arnold and British officials who were keen on restoring the Maha Bodhi Temple. Dhammika describes the efforts of Dharmapala elsewhere including in the neighbouring countries of Tibet, Burma, and the Thailand19. Dhammika also observes that the Indian National Congress, except for Gandhi was secular in outlook and so more favourably disposed to Buddhism than to Hindu practices20.

Dhammika records subsequent events at Maha Bodhi within the Indian body politic up to the 1990s. Hindus were despised by the recent Chief Minister of Bihar Laloo Yadav of the 1990s who came from a scheduled caste community discriminated for millennia by Brahmins. Yadav circulated a bill to hand over management of Bodh Gaya completely to the Buddhists and to ban Hindu marriages there21. In the 1990s and afterwards, those who were converted to Buddhism from Dalit (untouchable) castes by Ambedkar and his followers also entered the fray on the side of the Buddhists. All these recent actions had indirect Sinhalese influences arising from the 19th century and 20th century connections with the Sinhalese Renaissance.

Allen: British India discovers Buddhism

Charles Allen in his The Buddha and the Sahibs treads on somewhat similar grounds as Dhammika and others discussed here in "the discovery" of Buddhism in the 19th and early 20th century by non-Buddhists. Allen was born and lived in India where six generations of his family served the British Raj. His other books have traced many facets of the British presence in the subcontinent. This time, he has turned to the discovery of Buddhism by the British.

Allen observes that Muslim invaders had destroyed Buddhist sites and this destruction continued till the arrival of the British, when it was reversed by British archaeologists. The "sahibs" of his narrative are not the Western Orientalists of Edward Said who distorted Middle East history through colonial lenses. The persons, Allen describes, were products of the European Enlightenment in the late 18th century. A key link in the Western discovery of Buddhism, Allen recalls, was the Asiatic Society founded by Sir William Jones in the latter part of the 18th century22. Allen also notes that even William Jones, the founder of the Asiatic Society of Calcutta believed firmly that history began with Adam and Eve and the Flood. Initially, these early British Orientalists arrived at some laughable conclusions such as the Buddha being African in origin or that the British Isles were included within the Hindu cosmography.

Many of the young British men who came to India in the 18th century were from a genteel background with a solid grounding in the Western Classics, mathematics and philosophy. Through their background in Western Classics, they were aware of the impressions of India of Alexander the Great as well as of Megasthenes, the Greek ambassador in the Mauryan court of Pataliputra. However, when these British hopefuls came ashore to India, they entered a country without a past, India's past not been yet written24. A Sinhalese connection gave key parts of this past.

Allen delves into the Sinhalese connection in the discovery of Indian Buddhism. He begins his sympathetic story when a party of travellers came to Bihar -- the land of Buddhist monasteries -- viharas. In the party was Dr Francis Buchanan an employee of the East India Company and a botanist. He was to gain prominence by bringing information about the religious edifices in Burma. And in 1797, he would make the first serious account in English of the Buddhist religion through his On the Religion and Literature of the Burmas25.

Allen traces the historical memory of Buddhism in the Western imagination from various Greek, Latin and Arabic sources. The writings of Marco Polo on Sri Lanka were the first description of a Buddhist country. Marco Polo (1254 - 1324 A.C.) described what he says the Muslims believed to be "Adam's Peak" but the Sinhalese calling it "Sakyamuni Burkhan's tomb -- clearly a corruption of Sakyamuni Buddha. Marco Polo in the recent translation from the Italian cited by Allen is described as giving a fairly accurate description of the life of Siddhartha from the time of his renunciation which Polo had got from Sinhala sources. Polo says that the Sinhalese believed that Adams Peak contains the teeth, hair and begging bowl of the Buddha. To obtain these, the Chinese emperor, Kublai Khan had sent an embassy in 1284 to Sri Lanka26.

CHAPTER XV. THE SAME CONTINUED. THE HISTORY OF SAGAMONI BORCAN [SAKYA-MUNI] AND THE BEGINNING OF IDOLATRY.

Furthermore you must know that in the Island of Seilan there is an exceeding high mountain; it rises right up so steep and precipitous that no one could ascend it, were it not that they have taken and fixed to it several great and massive iron chains, so disposed that by help of these men are able to mount to the top. And I tell you they say that on this mountain is the sepulchre of Adam our first parent; at least that is what the Saracens say. But the Idolaters say that it is the sepulchre of SAGAMONI BORCAN, before whose time there were no idols. They hold him to have been the best of men, a great saint in fact, according to their fashion, and the first in whose name idols were made.[NOTE 1]

He was the son, as their story goes, of a great and wealthy king. And he was of such an holy temper that he would never listen to any worldly talk, nor would he consent to be king. And when the father saw that his son would not be king, nor yet take any part in affairs, he took it sorely to heart. And first he tried to tempt him with great promises, offering to crown him king, and to surrender all authority into his hands. The son, however, would none of his offers; so the father was in great trouble, and all the more that he had no other son but him, to whom he might bequeath the kingdom at his own death. So, after taking thought on the matter, the King caused a great palace to be built, and placed his son therein, and caused him to be waited on there by a number of maidens, the most beautiful that could anywhere be found. And he ordered them to divert themselves with the prince, night and day, and to sing and dance before him, so as to draw his heart towards worldly enjoyments. But 'twas all of no avail, for none of those maidens could ever tempt the king's son to any wantonness, and he only abode the firmer in his chastity, leading a most holy life, after their manner thereof. And I assure you he was so staid a youth that he had never gone out of the palace, and thus he had never seen a dead man, nor any one who was not hale and sound; for the father never allowed any man that was aged or infirm to come into his presence. It came to pass however one day that the young gentleman took a ride, and by the roadside he beheld a dead man. The sight dismayed him greatly, as he never had seen such a sight before. Incontinently he demanded of those who were with him what thing that was? and then they told him it was a dead man. "How, then," quoth the king's son, "do all men die?" "Yea, forsooth," said they. Whereupon the young gentleman said never a word, but rode on right pensively. And after he had ridden a good way he fell in with a very aged man who could no longer walk, and had not a tooth in his head, having lost all because of his great age. And when the king's son beheld this old man he asked what that might mean, and wherefore the man could not walk? Those who were with him replied that it was through old age the man could walk no longer, and had lost all his teeth. And so when the king's son had thus learned about the dead man and about the aged man, he turned back to his palace and said to himself that he would abide no longer in this evil world, but would go in search of Him Who dieth not, and Who had created him.[NOTE 2]

So what did he one night but take his departure from the palace privily, and betake himself to certain lofty and pathless mountains. And there he did abide, leading a life of great hardship and sanctity, and keeping great abstinence, just as if he had been a Christian. Indeed, an he had but been so, he would have been a great saint of Our Lord Jesus Christ, so good and pure was the life he led.[NOTE 3] And when he died they found his body and brought it to his father. And when the father saw dead before him that son whom he loved better than himself, he was near going distraught with sorrow. And he caused an image in the similitude of his son to be wrought in gold and precious stones, and caused all his people to adore it. And they all declared him to be a god; and so they still say. [NOTE 4]

They tell moreover that he hath died fourscore and four times. The first time he died as a man, and came to life again as an ox; and then he died as an ox and came to life again as a horse, and so on until he had died fourscore and four times; and every time he became some kind of animal. But when he died the eighty-fourth time they say he became a god. And they do hold him for the greatest of all their gods. And they tell that the aforesaid image of him was the first idol that the Idolaters ever had; and from that have originated all the other idols. And this befel in the Island of Seilan in India.

The Idolaters come thither on pilgrimage from very long distances and with great devotion, just as Christians go to the shrine of Messer Saint James in Gallicia. And they maintain that the monument on the mountain is that of the king's son, according to the story I have been telling you; and that the teeth, and the hair, and the dish that are there were those of the same king's son, whose name was Sagamoni Borcan, or Sagamoni the Saint. But the Saracens also come thither on pilgrimage in great numbers, and they say that it is the sepulchre of Adam our first father, and that the teeth, and the hair, and the dish were those of Adam.[NOTE 5]

Whose they were in truth, God knoweth; howbeit, according to the Holy Scripture of our Church, the sepulchre of Adam is not in that part of the world.

Now it befel that the Great Kaan heard how on that mountain there was the sepulchre of our first father Adam, and that some of his hair and of his teeth, and the dish from which he used to eat, were still preserved there. So he thought he would get hold of them somehow or another, and despatched a great embassy for the purpose, in the year of Christ, 1284. The ambassadors, with a great company, travelled on by sea and by land until they arrived at the island of Seilan, and presented themselves before the king. And they were so urgent with him that they succeeded in getting two of the grinder teeth, which were passing great and thick; and they also got some of the hair, and the dish from which that personage used to eat, which is of a very beautiful green porphyry. And when the Great Kaan's ambassadors had attained the object for which they had come they were greatly rejoiced, and returned to their lord. And when they drew near to the great city of Cambaluc, where the Great Kaan was staying, they sent him word that they had brought back that for which he had sent them. On learning this the Great Kaan was passing glad, and ordered all the ecclesiastics and others to go forth to meet these reliques, which he was led to believe were those of Adam.

And why should I make a long story of it? In sooth, the whole population of Cambaluc went forth to meet those reliques, and the ecclesiastics took them over and carried them to the Great Kaan, who received them with great joy and reverence.[NOTE 6] And they find it written in their Scriptures that the virtue of that dish is such that if food for one man be put therein it shall become enough for five men: and the Great Kaan averred that he had proved the thing and found that it was really true.[NOTE 7]

So now you have heard how the Great Kaan came by those reliques; and a mighty great treasure it did cost him! The reliques being, according to the Idolaters, those of that king's son.

NOTE 1.—Sagamoni Borcan is, as Marsden points out, SAKYA-MUNI, or Gautama-Buddha, with the affix BURKHAN, or "Divinity," which is used by the Mongols as the synonym of Buddha.

"The Dewa of Samantakúta (Adam's Peak), Samana, having heard of the arrival of Budha (in Lanka or Ceylon) … presented a request that he would leave an impression of his foot upon the mountain of which he was guardian…. In the midst of the assembled Dewas, Budha, looking towards the East, made the impression of his foot, in length three inches less than the cubit of the carpenter; and the impression remained as a seal to show that Lanka is the inheritance of Budha, and that his religion will here flourish." (Hardy's Manual, p. 212.)

[Ma-Huan says (p. 212): "On landing (at Ceylon), there is to be seen on the shining rock at the base of the cliff, an impress of a foot two or more feet in length. The legend attached to it is, that it is the imprint of Shâkyamuni's foot, made when he landed at this place, coming from the Ts'ui-lan (Nicobar) Islands. There is a little water in the hollow of the imprint of this foot, which never evaporates. People dip their hands in it and wash their faces, and rub their eyes with it, saying: 'This is Buddha's water, which will make us pure and clean.'"—H.C.]

[Illustration: Adam's Peak. "Or est voir qe en ceste ysle a une montagne mont haut et si degrot de les rocches qe nul hi puent monter sus se ne en ceste mainere qe je voz dirai"….]

"The veneration with which this majestic mountain has been regarded for ages, took its rise in all probability amongst the aborigines of Ceylon…. In a later age, … the hollow in the lofty rock that crowns the summit was said by the Brahmans to be the footstep of Siva, by the Buddhists of Buddha, … by the Gnostics of Ieu, by the Mahometans of Adam, whilst the Portuguese authorities were divided between the conflicting claims of St. Thomas and the eunuch of Candace, Queen of Ethiopia." (Tennent, II. 133.)

["Near to the King's residence there is a lofty mountain reaching to the skies. On the top of this mountain there is the impress of a man's foot, which is sunk two feet deep in the rock, and is some eight or more feet long. This is said to be the impress of the foot of the ancestor of mankind, a Holy man called A-tan, otherwise P'an-Ku." (Ma-Huan, p. 213.)—H.C.]

Polo, however, says nothing of the foot; he speaks only of the sepulchre of Adam, or of Sakya-muni. I have been unable to find any modern indication of the monument that was shown by the Mahomedans as the tomb, and sometimes as the house, of Adam; but such a structure there certainly was, perhaps an ancient Kist-vaen, or the like. John Marignolli, who was there about 1349, has an interesting passage on the subject: "That exceeding high mountain hath a pinnacle of surpassing height, which on account of the clouds can rarely be seen. [The summit is lost in the clouds. (Ibn Khordâdhbeh, p. 43.)—H.C.] But God, pitying our tears, lighted it up one morning just before the sun rose, so that we beheld it glowing with the brightest flame. [They say that a flame bursts constantly, like a lightning, from the Summit of the mountain.—(Ibn Khordâdhbeh, p. 44.)—H.C.] In the way down from this mountain there is a fine level spot, still at a great height, and there you find in order: first, the mark of Adam's foot; secondly, a certain statue of a sitting figure, with the left hand resting on the knee, and the right hand raised and extended towards the west; lastly, there is the house (of Adam), which he made with his own hands. It is of an oblong quadrangular shape like a sepulchre, with a door in the middle, and is formed of great tabular slabs of marble, not cemented, but merely laid one upon another. (Cathay, 358.) A Chinese account, translated in Amyot's Mémoires, says that at the foot of the mountain is a Monastery of Bonzes, in which is seen the veritable body of Fo, in the attitude of a man lying on his side" (XIV. 25). [Ma-Huan says (p. 212): "Buddhist temples abound there. In one of them there is to be seen a full length recumbent figure of Shâkyamuni, still in a very good state of preservation. The dais on which the figure reposes is inlaid with all kinds of precious stones. It is made of sandalwood and is very handsome. The temple contains a Buddha's tooth and other relics. This must certainly be the place where Shâkyamuni entered Nirvâna."—H.C.] Osorio, also, in his history of Emanuel of Portugal, says: "Not far from it (the Peak) people go to see a small temple in which are two sepulchres, which are the objects of an extraordinary degree of superstitious devotion. For they believe that in these were buried the bodies of the first man and his wife" (f. 120 v.). A German traveller (Daniel Parthey, Nurnberg, 1698) also speaks of the tomb of Adam and his sons on the mountain. (See Fabricius, Cod. Pseudep. Vet. Test. II. 31; also Ouseley's Travels, I. 59.)

It is a perplexing circumstance that there is a double set of indications about the footmark. The Ceylon traditions, quoted above from Hardy, call its length 3 inches less than a carpenter's cubit. Modern observers estimate it at 5 feet or 5-1/2 feet. Hardy accounts for this by supposing that the original footmark was destroyed in the end of the sixteenth century. But Ibn Batuta, in the 14th, states it at 11 spans, or more than the modern report. [Ibn Khordâdhbeh at 70 cubits.—H.C.] Marignolli, on the other hand, says that he measured it and found it to be 2-1/2 palms, or about half a Prague ell, which corresponds in a general way with Hardy's tradition. Valentyn calls it 1-1/2 ell in length; Knox says 2 feet; Herman Bree (De Bry ?), quoted by Fabricius, 8-1/2 spans; a Chinese account, quoted below, 8 feet. These discrepancies remind one of the ancient Buddhist belief regarding such footmarks, that they seemed greater or smaller in proportion to the faith of the visitor! (See Koeppen, I. 529, and Beal's Fah-hian, p. 27.)

The chains, of which Ibn Batuta gives a particular account, exist still. The highest was called (he says) the chain of the Shahádat, or Credo, because the fearful abyss below made pilgrims recite the profession of belief. Ashraf, a Persian poet of the 15th century, author of an Alexandriad, ascribes these chains to the great conqueror, who devised them, with the assistance of the philosopher Bolinas,[1] in order to scale the mountain, and reach the sepulchre of Adam. (See Ouseley, I. 54 seqq.) There are inscriptions on some of the chains, but I find no account of them. (Skeen's Adam's Peak, Ceylon, 1870, p. 226.)

NOTE 2.—The general correctness with which Marco has here related the legendary history of Sakya's devotion to an ascetic life, as the preliminary to his becoming the Buddha or Divinely Perfect Being, shows what a strong impression the tale had made upon him. He is, of course, wrong in placing the scene of the history in Ceylon, though probably it was so told him, as the vulgar in all Buddhist countries do seem to localise the legends in regions known to them.

Sakya Sinha, Sakya Muni, or Gautama, originally called Siddhárta, was the son of Súddhodhana, the Kshatriya prince of Kapilavastu, a small state north of the Ganges, near the borders of Oudh. His high destiny had been foretold, as well as the objects that would move him to adopt the ascetic life. To keep these from his knowledge, his father caused three palaces to be built, within the limits of which the prince should pass the three seasons of the year, whilst guards were posted to bar the approach of the dreaded objects. But these precautions were defeated by inevitable destiny and the power of the Devas.

When the prince was sixteen he was married to the beautiful Yasodhara, daughter of the King of Koli, and 40,000 other princesses also became the inmates of his harem.

"Whilst living in the midst of the full enjoyment of every kind of pleasure, Siddhárta one day commanded his principal charioteer to prepare his festive chariot; and in obedience to his commands four lily-white horses were yoked. The prince leaped into the chariot, and proceeded towards a garden at a little distance from the palace, attended by a great retinue. On his way he saw a decrepit old man, with broken teeth, grey locks, and a form bending towards the ground, his trembling steps supported by a staff (a Deva had taken this form)…. The prince enquired what strange figure it was that he saw; and he was informed that it was an old man. He then asked if the man was born so, and the charioteer answered that he was not, as he was once young like themselves. 'Are there,' said the prince, 'many such beings in the world?' 'Your highness,' said the charioteer, 'there are many.' The prince again enquired, 'Shall I become thus old and decrepit?' and he was told that it was a state at which all beings must arrive."

The prince returns home and informs his father of his intention to become an ascetic, seeing how undesirable is life tending to such decay. His father conjures him to put away such thoughts, and to enjoy himself with his princesses, and he strengthens the guards about the palaces. Four months later like circumstances recur, and the prince sees a leper, and after the same interval a dead body in corruption. Lastly, he sees a religious recluse, radiant with peace and tranquillity, and resolves to delay no longer. He leaves his palace at night, after a look at his wife Yasodhara and the boy just born to him, and betakes himself to the forests of Magadha, where he passes seven years in extreme asceticism. At the end of that time he attains the Buddhahood. (See Hardy's Manual p. 151 seqq.) The latter part of the story told by Marco, about the body of the prince being brought to his father, etc., is erroneous. Sakya was 80 years of age when he died under the sál trees in Kusinára.

The strange parallel between Buddhistic ritual, discipline, and costume, and those which especially claim the name of CATHOLIC in the Christian Church, has been often noticed; and though the parallel has never been elaborated as it might be, some of the more salient facts are familiar to most readers. Still many may be unaware that Buddha himself, Siddhárta the son of Súddodhana, has found his way into the Roman martyrology as a Saint of the Church.

In the first edition a mere allusion was made to this singular story, for it had recently been treated by Professor Max Müller, with characteristic learning and grace. (See Contemporary Review for July, 1870, p. 588.) But the matter is so curious and still so little familiar that I now venture to give it at some length.

The religious romance called the History of BARLAAM and JOSAPHAT was for several centuries one of the most popular works in Christendom. It was translated into all the chief European languages, including Scandinavian and Sclavonic tongues. An Icelandic version dates from the year 1204; one in the Tagal language of the Philippines was printed at Manilla in 1712.[2] The episodes and apologues with which the story abounds have furnished materials to poets and story-tellers in various ages and of very diverse characters; e.g. to Giovanni Boccaccio, John Gower, and to the compiler of the Gesta Romanorum, to Shakspere, and to the late W. Adams, author of the Kings Messengers. The basis of this romance is the story of Siddhárta.

The story of Barlaam and Josaphat first appears among the works (in Greek) of St. John of Damascus, a theologian of the early part of the 8th century, who, before he devoted himself to divinity had held high office at the Court of the Khalif Abu Jáfar Almansúr. The outline of the story is as follows:—

St. Thomas had converted the people of India to the truth; and after the eremitic life originated in Egypt many in India adopted it. But a potent pagan King arose, by name ABENNER, who persecuted the Christians and especially the ascetics. After this King had long been childless, a son, greatly desired, is born to him, a boy of matchless beauty. The King greatly rejoices, gives the child the name of JOSAPHAT, and summons the astrologers to predict his destiny. They foretell for the prince glory and prosperity beyond all his predecessors in the kingdom. One sage, most learned of all, assents to this, but declares that the scene of these glories will not be the paternal realm, and that the child will adopt the faith that his father persecutes.

This prediction greatly troubled King Abenner. In a secluded city he caused a splendid palace to be erected, within which his son was to abide, attended only by tutors and servants in the flower of youth and health. No one from without was to have access to the prince; and he was to witness none of the afflictions of humanity, poverty, disease, old age, or death, but only what was pleasant, so that he should have no inducement to think of the future life; nor was he ever to hear a word of CHRIST or His religion. And, hearing that some monks still survived in India, the King in his wrath ordered that any such, who should be found after three days, should be burnt alive.

The Prince grows up in seclusion, acquires all manner of learning, and exhibits singular endowments of wisdom and acuteness. At last he urges his father to allow him to pass the limits of the palace, and this the King reluctantly permits, after taking all precautions to arrange diverting spectacles, and to keep all painful objects at a distance. Or let us proceed in the Old English of the Golden Legend.[3] "Whan his fader herde this he was full of sorowe, and anone he let do make redy horses and joyfull felawshyp to accompany him, in suche wyse that nothynge dyshonest sholde happen to hym. And on a tyme thus as the Kynges sone wente he mette a mesell and a blynde man, and whã he sawe them he was abasshed and enquyred what them eyled. And his seruautes sayd: These ben passions that comen to men. And he demaunded yf the passyons came to all men. And they sayd nay. Thã sayd he, ben they knowen whiche men shall suffre…. And they answered, Who is he that may knowe ye aduentures of men. And he began to be moche anguysshous for ye incustomable thynge hereof. And another tyme he found a man moche aged, whiche had his chere frouced, his tethe fallen, and he was all croked for age…. And thã he demaunded what sholde be ye ende. And they sayd deth…. And this yonge man remembered ofte in his herte these thynges, and was in grete dyscõforte, but he shewed hy moche glad tofore his fader, and he desyred moche to be enformed and taught in these thyges." [Fol. ccc. lii.]

At this time BARLAAM, a monk of great sanctity and knowledge in divine things, who dwelt in the wilderness of Sennaritis, having received a divine warning, travels to India in the disguise of a merchant, and gains access to Prince Josaphat, to whom he unfolds the Christian doctrine and the blessedness of the monastic life. Suspicion is raised against Barlaam, and he departs. But all efforts to shake the Prince's convictions are vain. As a last resource the King sends for a magician called Theudas, who removes the Prince's attendants and substitutes seductive girls, but all their blandishments are resisted through prayer. The King abandons these attempts and associates his son with himself in the government. The Prince uses his power to promote religion, and everything prospers in his hand. Finally King Abenner is drawn to the truth, and after some years of penitence dies. Josaphat then surrenders the kingdom to a friend called Barachias, and proceeds into the wilderness, where he wanders for two years seeking Barlaam, and much buffeted by the demons. "And whan Balaam had accomplysshed his dayes, he rested in peas about ye yere of Our Lorde. cccc. &. Ixxx. Josaphat lefte his realme the xxv. yere of his age, and ledde the lyfe of an heremyte xxxv. yere, and than rested in peas full of vertues, and was buryed by the body of Balaam." [Fol. ccc. lvi.] The King Barachias afterwards arrives and transfers the bodies solemnly to India.

This is but the skeleton of the story, but the episodes and apologues which round its dimensions, and give it its mediaeval popularity, do not concern our subject. In this skeleton the story of Siddhárta, mutatis mutandis is obvious.

The story was first popular in the Greek Church, and was embodied in the lives of the saints, as recooked by Simeon the Metaphrast, an author whose period is disputed, but was in any case not later than 1150. A Cretan monk called Agapios made selections from the work of Simeon which were published in Romaic at Venice in 1541 under the name of the Paradise, and in which the first section consists of the story of Barlaam and Josaphat. This has been frequently reprinted as a popular book of devotion. A copy before me is printed at Venice in 1865.[4]

From the Greek Church the history of the two saints passed to the Latin, and they found a place in the Roman martyrology under the 27th November. When this first happened I have not been able to ascertain. Their history occupies a large space in the Speculum Historiale of Vincent of Beauvais, written in the 13th century, and is set forth, as we have seen, in the Golden Legend of nearly the same age. They are recognised by Baronius, and are to be found at p. 348 of "The Roman Martyrology set forth by command of Pope Gregory XIII., and revised by the authority of Pope Urban VIII., translated out of Latin into English by G.K. of the Society of Jesus…. and now re-edited … by W.N. Skelly, Esq. London, T. Richardson & Son." (Printed at Derby, 1847.) Here in Palermo is a church bearing the dedication Divo Iosaphat.

Professor Müller attributes the first recognition of the identity of the two stories to M. Laboulaye in 1859. But in fact I find that the historian de Couto had made the discovery long before.[5] He says, speaking of Budão (Buddha), and after relating his history:

"To this name the Gentiles throughout all India have dedicated great and superb pagodas. With reference to this story we have been diligent in enquiring if the ancient Gentiles of those parts had in their writings any knowledge of St. Josaphat who was converted by Barlam, who in his Legend is represented as the son of a great King of India, and who had just the same up-bringing, with all the same particulars, that we have recounted of the life of the Budão…. And as a thing seems much to the purpose, which was told us by a very old man of the Salsette territory in Baçaim, about Josaphat, I think it well to cite it: As I was travelling in the Isle of Salsette, and went to see that rare and admirable Pagoda (which we call the Canará Pagoda[6]) made in a mountain, with many halls cut out of one solid rock … and enquiring from this old man about the work, and what he thought as to who had made it, he told us that without doubt the work was made by order of the father of St. Josaphat to bring him up therein in seclusion, as the story tells. And as it informs us that he was the son of a great King in India, it may well be, as we have just said, that he was the Budão, of whom they relate such marvels." (Dec. V. liv. vi. cap. 2.)

Dominie Valentyn, not being well read in the Golden Legend, remarks on the subject of Buddha: "There be some who hold this Budhum for a fugitive Syrian Jew, or for an Israelite, others who hold him for a Disciple of the Apostle Thomas; but how in that case he could have been born 622 years before Christ I leave them to explain. Diego de Couto stands by the belief that he was certainly Joshua, which is still more absurd!" (V. deel, p. 374.)

[Since the days of Couto, who considered the Buddhist legend but an imitation of the Christian legend, the identity of the stories was recognised (as mentioned supra) by M. Edouard Laboulaye, in the Journal des Débats of the 26th of July, 1859. About the same time, Professor F. Liebrecht of Liége, in Ebert's Jahrbuch für Romanische und Englische Literatur, II. p. 314 seqq., comparing the Book of Barlaam and Joasaph with the work of Barthélemy St. Hilaire on Buddha, arrived at the same conclusion.

In 1880, Professor T.W. Rhys Davids has devoted some pages (xxxvi.-xli.) in his Buddhist Birth Stories; or, Jataka Tales, to The Barlaam and Josaphat Literature, and we note from them that: "Pope Sixtus the Fifth (1585-1590) authorised a particular Martyrologium, drawn up by Cardinal Baronius, to be used throughout the Western Church.". In that work are included not only the saints first canonised at Rome, but all those who, having been already canonised elsewhere, were then acknowledged by the Pope and the College of Rites to be saints of the Catholic Church of Christ. Among such, under the date of the 27th of November, are included "The holy Saints Barlaam and Josaphat, of India, on the borders of Persia, whose wonderful acts Saint John of Damascus has described. Where and when they were first canonised, I have been unable, in spite of much investigation, to ascertain. Petrus de Natalibus, who was Bishop of Equilium, the modern Jesolo, near Venice, from 1370 to 1400, wrote a Martyrology called Catalogus Sanctorum; and in it, among the 'Saints,' he inserts both Barlaam and Josaphat, giving also a short account of them derived from the old Latin translation of St. John of Damascus. It is from this work that Baronius, the compiler of the authorised Martyrology now in use, took over the names of these two saints, Barlaam and Josaphat. But, so far as I have been able to ascertain, they do not occur in any martyrologies or lists of saints of the Western Church older than that of Petrus de Natalibus. In the corresponding manual of worship still used in the Greek Church, however, we find, under 26th August, the name 'of the holy Iosaph, son of Abener, King of India.' Barlaam is not mentioned, and is not therefore recognised as a saint in the Greek Church. No history is added to the simple statement I have quoted; and I do not know on what authority it rests. But there is no doubt that it is in the East, and probably among the records of the ancient church of Syria, that a final solution of this question should be sought. Some of the more learned of the numerous writers who translated or composed new works on the basis of the story of Josaphat, have pointed out in their notes that he had been canonised; and the hero of the romance is usually called St. Josaphat in the titles of these works, as will be seen from the Table of the Josaphat literature below. But Professor Liebrecht, when identifying Josaphat with the Buddha, took no notice of this; and it was Professor Max Müller, who has done so much to infuse the glow of life into the dry bones of Oriental scholarship, who first pointed out the strange fact—almost incredible, were it not for the completeness of the proof—that Gotama the Buddha, under the name of St. Josaphat, is now officially recognised and honoured and worshipped throughout the whole of Catholic Christendom as a Christian saint!" Professor T.W. Rhys Davids gives further a Bibliography, pp. xcv.-xcvii.

M.H. Zotenberg wrote a learned memoir (N. et Ext. XXVIII. Pt. I.) in 1886 to prove that the Greek Text is not a translation but the original of the Legend. There are many MSS. of the Greek Text of the Book of Barlaam and Joasaph in Paris, Vienna, Munich, etc., including ten MSS. kept in various libraries at Oxford. New researches made by Professor E. Kuhn, of Munich (Barlaam und Joasaph. Eine Bibliographisch-literargeschichtliche Studie, 1893), seem to prove that during the 6th century, in that part of the Sassanian Empire bordering on India, in fact Afghanistan, Buddhism and Christianity were gaining ground at the expense of the Zoroastrian faith, and that some Buddhist wrote in Pehlevi a Book of Yûdâsaf (Bodhisatva); a Christian, finding pleasant the legend, made an adaptation of it from his own point of view, introducing the character of the monk Balauhar (Barlaam) to teach his religion to Yûdâsaf, who could not, in his Christian disguise, arrive at the truth by himself like a Bodhisatva. This Pehlevi version of the newly-formed Christian legend was translated into Syriac, and from Syriac was drawn a Georgian version, and, in the first half of the 7th century, the Greek Text of John, a monk of the convent of St. Saba, near Jerusalem, by some turned into St. John of Damascus, who added to the story some long theological discussions. From this Greek, it was translated into all the known languages of Europe, while the Pehlevi version being rendered into Arabic, was adapted by the Mussulmans and the Jews to their own creeds. (H. Zotenberg, Mém. sur le texte et les versions orientales du Livre de Barlaam et Joasaph, Not. et Ext. XXVIII. Pt. I. pp. 1-166; G. Paris, Saint Josaphat in Rev. de Paris, 1'er Juin, 1895, and Poèmes et Légendes du Moyen Age, pp. 181-214.)

Mr. Joseph Jacobs published in London, 1896, a valuable little book, Barlaam and Josaphat, English Lives of Buddha, in which he comes to this conclusion (p. xli.): "I regard the literary history of the Barlaam literature as completely parallel with that of the Fables of Bidpai. Originally Buddhistic books, both lost their specifically Buddhistic traits before they left India, and made their appeal, by their parables, more than by their doctrines. Both were translated into Pehlevi in the reign of Chosroes, and from that watershed floated off into the literatures of all the great creeds. In Christianity alone, characteristically enough, one of them, the Barlaam book, was surcharged with dogma, and turned to polemical uses, with the curious result that Buddha became one of the champions of the Church. To divest the Barlaam-Buddha of this character, and see him in his original form, we must take a further journey and seek him in his home beyond the Himalayas."

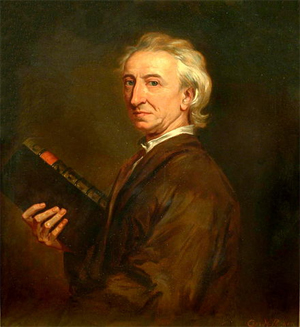

[Illustration: Sakya Muni as a Saint of the Roman Martyrology. "Wie des Kunigs Son in dem aufscziechen am ersten sahe in dem Weg eynen blinden und eyn aufsmörckigen und eyen alten krummen Man."[7]]

Professor Gaston Paris, in answer to Mr. Jacobs, writes (Poèmes et Lég. du Moyen Age, p. 213): "Mr. Jacobs thinks that the Book of Balauhar and Yûdâsaf was not originally Christian, and could have existed such as it is now in Buddhistic India, but it is hardly likely, as Buddha did not require the help of a teacher to find truth, and his followers would not have invented the person of Balauhar-Barlaam; on the other hand, the introduction of the Evangelical Parable of The Sower, which exists in the original of all the versions of our Book, shows that this original was a Christian adaptation of the Legend of Buddha. Mr. Jacobs seeks vainly to lessen the force of this proof in showing that this Parable has parallels in Buddhistic literature."—H.C.]

NOTE 3.—Marco is not the only eminent person who has expressed this view of Sakyamuni's life in such words. Professor Max Müller (u.s.) says: "And whatever we may think of the sanctity of saints, let those who doubt the right of Buddha to a place among them, read the story of his life as it is told in the Buddhistic canon. If he lived the life which is there described, few saints have a better claim to the title than Buddha; and no one either in the Greek or the Roman Church need be ashamed of having paid to his memory the honour that was intended for St. Josaphat, the prince, the hermit, and the saint."

NOTE 4.—This is curiously like a passage in the Wisdom of Solomon: "Neque enim erant (idola) ab initio, neque erunt in perpetuum … acerbo enim luctu dolens pater cito sibi rapti filii fecit imaginem: et ilium qui tune quasi homo mortuus fuerat nunc tamquam deum colere coepit, et constituit inter servos suos sacra et sacrificia" (xiv. 13-15). Gower alludes to the same story; I know not whence taken:—"Of Cirophanes, seith the booke,

That he for sorow, whiche he toke

Of that he sigh his sonne dede,

Of comfort knewe none other rede,

But lete do make in remembrance

A faire image of his semblance,

And set it in the market place:

Whiche openly to fore his face

Stood euery day, to done hym ease;

And thei that than wolden please

The Fader, shuld it obeye,

Whan that thei comen thilke weye."

—Confessio Amantis.[8]

NOTE 5.—Adam's Peak has for ages been a place of pilgrimage to Buddhists, Hindus, and Mahomedans, and appears still to be so. Ibn Batuta says the Mussulman pilgrimage was instituted in the 10th century. The book on the history of the Mussulmans in Malabar, called Tohfat-ul-Majáhidín (p. 48), ascribes their first settlement in that country to a party of pilgrims returning from Adam's Peak. Marignolli, on his visit to the mountain, mentions "another pilgrim, a Saracen of Spain; for many go on pilgrimage to Adam."

The identification of Adam with objects of Indian worship occurs in various forms. Tod tells how an old Rajput Chief, as they stood before a famous temple of Mahádeo near Udipúr, invited him to enter and worship "Father Adam." Another traveller relates how Brahmans of Bagesar on the Sarjú identified Mahadeo and Parvati with Adam and Eve. A Malay MS., treating of the origines of Java, represents Brahma, Mahadeo, and Vishnu to be descendants of Adam through Seth. And in a Malay paraphrase of the Ramáyana, Nabi Adam takes the place of Vishnu. (Tod. I. 96; J.A.S.B. XVI. 233; J.R.A.S. N.S. II. 102; J. Asiat. IV. s. VII. 438.)

NOTE 6.—The Pâtra, or alms-pot, was the most valued legacy of Buddha. It had served the three previous Buddhas of this world-period, and was destined to serve the future one, Maitreya. The Great Asoka sent it to Ceylon. Thence it was carried off by a Tamul chief in the 1st century, A.D., but brought back we know not how, and is still shown in the Malagawa Vihara at Kandy. As usual in such cases, there were rival reliques, for Fa-hian found the alms-pot preserved at Pesháwar. Hiuen Tsang says in his time it was no longer there, but in Persia. And indeed the Pâtra from Pesháwar, according to a remarkable note by Sir Henry Rawlinson, is still preserved at Kandahár, under the name of Kashkul (or the Begging-pot), and retains among the Mussulman Dervishes the sanctity and miraculous repute which it bore among the Buddhist Bhikshus. Sir Henry conjectures that the deportation of this vessel, the palladium of the true Gandhára (Pesháwar), was accompanied by a popular emigration, and thus accounts for the transfer of that name also to the chief city of Arachosia. (Koeppen, I. 526; Fah-hian, p. 36; H. Tsang, II. 106; J.R.A.S. XI. 127.)

Sir E. Tennent, through Mr. Wylie (to whom this book owes so much), obtained the following curious Chinese extract referring to Ceylon (written 1350): "In front of the image of Buddha there is a sacred bowl, which is neither made of jade nor copper, nor iron; it is of a purple colour, and glossy, and when struck it sounds like glass. At the commencement of the Yuen Dynasty (i.e. under Kúblái) three separate envoys were sent to obtain it." Sanang Setzen also corroborates Marco's statement: "Thus did the Khaghan (Kúblái) cause the sun of religion to rise over the dark land of the Mongols; he also procured from India images and reliques of Buddha; among others the Pâtra of Buddha, which was presented to him by the four kings (of the cardinal points), and also the chandana chu" (a miraculous sandal-wood image). (Tennent, I. 622; Schmidt, p. 119.)

The text also says that several teeth of Buddha were preserved in Ceylon, and that the Kaan's embassy obtained two molars. Doubtless the envoys were imposed on; no solitary case in the amazing history of that relique, for the Dalada, or tooth relique, seems in all historic times to have been unique. This, "the left canine tooth" of the Buddha, is related to have been preserved for 800 years at Dantapura ("Odontopolis"), in Kalinga, generally supposed to be the modern Púri or Jagannáth. Here the Brahmans once captured it and carried it off to Palibothra, where they tried in vain to destroy it. Its miraculous resistance converted the king, who sent it back to Kalinga. About A.D. 311 the daughter of King Guhasiva fled with it to Ceylon. In the beginning of the 14th century it was captured by the Tamuls and carried to the Pandya country on the continent, but recovered some years later by King Parakrama III., who went in person to treat for it. In 1560 the Portuguese got possession of it and took it to Goa. The King of Pegu, who then reigned, probably the most powerful and wealthy monarch who has ever ruled in Further India, made unlimited offers in exchange for the tooth; but the archbishop prevented the viceroy from yielding to these temptations, and it was solemnly pounded to atoms by the prelate, then cast into a charcoal fire, and finally its ashes thrown into the river of Goa.

The King of Pegu was, however, informed by a crafty minister of the King of Ceylon that only a sham tooth had been destroyed by the Portuguese, and that the real relique was still safe. This he obtained by extraordinary presents, and the account of its reception at Pegu, as quoted by Tennent from De Couto, is a curious parallel to Marco's narrative of the Great Kaan's reception of the Ceylon reliques at Cambaluc. The extraordinary object still so solemnly preserved at Kandy is another forgery, set up about the same time. So the immediate result of the viceroy's virtue was that two reliques were worshipped instead of one!

The possession of the tooth has always been a great object of desire to Buddhist sovereigns. In the 11th century King Anarauhta, of Burmah, sent a mission to Ceylon to endeavour to procure it, but he could obtain only a "miraculous emanation" of the relique. A tower to contain the sacred tooth was (1855), however, one of the buildings in the palace court of Amarapura. A few years ago the King of Burma repeated the mission of his remote predecessor, but obtained only a model, and this has been deposited within the walls of the palace at Mandalé, the new capital. (Turnour in J.A.S.B. VI. 856 seqq.; Koeppen, I. 521; Tennent, I. 388, II. 198 seqq.; MS. Note by Sir A. Phayre; Mission to Ava, 136.)

Of the four eye-teeth of Sakya, one, it is related, passed to the heaven of Indra; the second to the capital of Gandhára; the third to Kalinga; the fourth to the snake-gods. The Gandhára tooth was perhaps, like the alms-bowl, carried off by a Sassanid invasion, and may be identical with that tooth of Fo, which the Chinese annals state to have been brought to China in A.D. 530 by a Persian embassy. A tooth of Buddha is now shown in a monastery at Fu-chau; but whether this be either the Sassanian present, or that got from Ceylon by Kúblái, is unknown. Other teeth of Buddha were shown in Hiuen Tsang's time at Balkh, at Nagarahára (or Jalálábád), in Kashmir, and at Kanauj. (Koeppen, u.s.; Fortune, II. 108; H. Tsang, II. 31, 80, 263.)

[Illustration: Teeth of Budda. 1. At Kandy, after Tennent. 2. At Fu-Chau from Fortune.]

NOTE 7.—Fa-hian writes of the alms-pot at Pesháwar, that poor people could fill it with a few flowers, whilst a rich man should not be able to do so with 100, nay, with 1000 or 10,000 bushels of rice; a parable doubtless originally carrying a lesson, like Our Lord's remark on the widow's mite, but which hardened eventually into some foolish story like that in the text.

The modern Mussulman story at Kandahar is that the alms-pot will contain any quantity of liquor without overflowing.

This Pâtra is the Holy Grail of Buddhism. Mystical powers of nourishment are ascribed also to the Grail in the European legends. German scholars have traced in the romances of the Grail remarkable indications of Oriental origin. It is not impossible that the alms-pot of Buddha was the prime source of them. Read the prophetic history of the Pâtra as Fa-hian heard it in India (p. 161); its mysterious wanderings over Asia till it is taken up into the heaven Tushita where Maitreya the Future Buddha dwells. When it has disappeared from earth the Law gradually perishes, and violence and wickedness more and more prevail:—"What is it?

The phantom of a cup that comes and goes?

* * * * * If a man

Could touch or see it, he was heal'd at once,

By faith, of all his ills. But then the times

Grew to such evil that the holy cup

Was caught away to Heaven, and disappear'd."

—Tennyson's Holy Grail

-- The Travels of Marco Polo, by Marco Polo and Rustichello of Pisa: The Complete Yule-Cordier Edition