James Fraser (1713-1754)

by Wikisource

Accessed: 8/26/20

[from Preface and appendix to Fraser's History of Nadir Shah; manuscript notes, written about 1754 by S. Smalbroke (son of Dr. Richard Smalbroke [q. v.], bishop of Lichfield and Coventry) in a copy of that work now in the possession of W. Irvine, esq.; Note on James Fraser in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1899, pp. 214-20, by W. Irvine; Burke's Landed Gentry; Macray's Annals of the Bodleian Library, Oxford, 1890, pp. 216, 372, note 1; Aufrecht's Bodleian Sanskrit Catalogue, pp. 358, 403-4.]

FRASER, JAMES (1713–1754), author and collector of oriental manuscripts, born in 1713, was the son of Alexander Fraser (d. 1733) of Reelick, near Inverness. He paid two visits to India, where he resided at Surat. During his first stay (1730-40) he acquired a working knowledge of Zend from Parsi teachers and of Sanskrit from a learned Brahman. He also collected materials for an account of Nadir Shah, who invaded India in 1737-8. Coming home for about two years, he published his book. He then went out again as a factor in the East India Company's service, and became a member of the council at Surat, where he remained for six years. After his return in 1749 he expressed the intention of compiling an ancient Persian (Zend) lexicon, and of translating the Zendavesta from the original. He also spoke of translating the 'Vedh' (Veda) of the Brahmans; he seems, however, to have had no direct knowledge of the Vedas, but to have been acquainted with post-Vedic works only. Nothing came of these plans owing to his premature death, which took place at his own house, Easter Moniack, Inverness-shire, on 21 Jan. 1754 (Scots Mag. 1754, p. 51).

Fraser married in London, in 1742, Mary, only daughter of Edward Satchwell of Warwickshire, by whom he had issue one son and three daughters. A portrait of him is still in the possession of his descendants at Reelick House. James Baillie Fraser [q. v.] and William Fraser (1784?-1835) [q. v.] were his grandsons.

Fraser's book is entitled 'The History of Nadir Shah, formerly called Thamas Kuli Khan, the present Emperor of Persia; to which is prefixed a short History of the Moghol Emperors' (London, 1742). It contains a map of the Moghul empire and part of Tartary. It was the first book in English treating of Nadir Shah, 'the scourge of God.' It is important not only as a first-hand contribution to the history of contemporary events, but also for the number of original documents which it alone has preserved.

At the end of his book the author gives a list of about two hundred oriental manuscripts, including Zend and Sanskrit, which he had purchased at Surat, Cambay, and Ahmedabad. His claim that his 'Sanskerrit' manuscripts formed 'the first collection of that kind ever brought into Europe' appears to be valid, though single Sanskrit manuscripts had reached England and France even earlier. After his death his oriental manuscripts were bought from his widow for the Radclifte Library at Oxford; they were transferred to the Bodleian on 10 May 1872. One of Fraser's manuscripts, containing 178 portraits of Indian kings down to Aurengzebe, found its way directly into the Bodleian as early as 1737, in which year it was presented to the library by the poet Alexander Pope, its then possessor. Fraser's Sanskrit manuscripts, forty-one in number and all post-Vedic, were the earliest collection in that language which came into the possession of Oxford University: the first Sanskrit manuscript, however, which the Bodleian acquired was given to it in 1666 by John Ken, an East India merchant of London. It was in order to inspect Fraser's Zend manuscripts that the famous French orientalist, Anquetil Duperron, visited Oxford in 1702, when brought a prisoner of war to England.

Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

Utopian socialism

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/26/20

Utopian socialism is the first current of modern socialism and socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, Étienne Cabet,...

Robert Owen and Henry George.[1][2] Utopian socialism is often described as the presentation of visions and outlines for imaginary or futuristic ideal societies, with positive ideals being the main reason for moving society in such a direction. Later socialists and critics of utopian socialism viewed utopian socialism as not being grounded in actual material conditions of existing society and in some cases as reactionary. These visions of ideal societies competed with Marxist-inspired revolutionary social democratic movements.[3]

As a term or label, utopian socialism is most often applied to, or used to define, those socialists who lived in the first quarter of the 19th century who were ascribed the label utopian by later socialists as a pejorative in order to imply naiveté and to dismiss their ideas as fanciful and unrealistic.[4] A similar school of thought that emerged in the early 20th century which makes the case for socialism on moral grounds is ethical socialism.[5]

One key difference between utopian socialists and other socialists such as most anarchists and Marxists is that utopian socialists generally do not believe any form of class struggle or social revolution is necessary for socialism to emerge. Utopian socialists believe that people of all classes can voluntarily adopt their plan for society if it is presented convincingly.[3] They feel their form of cooperative socialism can be established among like-minded people within the existing society and that their small communities can demonstrate the feasibility of their plan for society.[3]

Definition

See also: Utopia

The thinkers identified as utopian socialist did not use the term utopian to refer to their ideas. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels were the first thinkers to refer to them as utopian, referring to all socialist ideas that simply presented a vision and distant goal of an ethically just society as utopian. This utopian mindset which held an integrated conception of the goal, the means to produce said goal and an understanding of the way that those means would inevitably be produced through examining social and economic phenomena can be contrasted with scientific socialism which has been likened to Taylorism.[citation needed]

This distinction was made clear in Engels' work Socialism: Utopian and Scientific (1892, part of an earlier publication, the Anti-Dühring from 1878). Utopian socialists were seen as wanting to expand the principles of the French revolution in order to create a more rational society. Despite being labeled as utopian by later socialists, their aims were not always utopian and their values often included rigid support for the scientific method and the creation of a society based upon scientific understanding.[6]

Development

The term utopian socialism was introduced by Karl Marx in "For a Ruthless Criticism of Everything" in 1843 and then developed in The Communist Manifesto in 1848, although shortly before its publication Marx had already attacked the ideas of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in The Poverty of Philosophy (originally written in French, 1847). The term was used by later socialist thinkers to describe early socialist or quasi-socialist intellectuals who created hypothetical visions of egalitarian, communalist, meritocratic, or other notions of perfect societies without considering how these societies could be created or sustained.

In The Poverty of Philosophy, Marx criticized the economic and philosophical arguments of Proudhon set forth in The System of Economic Contradictions, or The Philosophy of Poverty. Marx accused Proudhon of wanting to rise above the bourgeoisie. In the history of Marx's thought and Marxism, this work is pivotal in the distinction between the concepts of utopian socialism and what Marx and the Marxists claimed as scientific socialism. Although utopian socialists shared few political, social, or economic perspectives, Marx and Engels argued that they shared certain intellectual characteristics. In The Communist Manifesto, Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote: "The undeveloped state of the class struggle, as well as their own surroundings, causes Socialists of this kind to consider themselves far superior to all class antagonisms. They want to improve the condition of every member of society, even that of the most favored. Hence, they habitually appeal to society at large, without distinction of class; nay, by preference, to the ruling class. For how can people, when once they understand their system, fail to see it in the best possible plan of the best possible state of society? Hence, they reject all political, and especially all revolutionary, action; they wish to attain their ends by peaceful means, and endeavor, by small experiments, necessarily doomed to failure, and by the force of example, to pave the way for the new social Gospel".[7]

Marx and Engels associated utopian socialism with communitarian socialism which similarly sees the establishment of small intentional communities as both a strategy for achieving and the final form of a socialist society.[8] Marx and Engels used the term scientific socialism to describe the type of socialism they saw themselves developing. According to Engels, socialism was not "an accidental discovery of this or that ingenious brain, but the necessary outcome of the struggle between two historically developed classes, namely the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. Its task was no longer to manufacture a system of society as perfect as possible, but to examine the historical-economic succession of events from which these classes and their antagonism had of necessity sprung, and to discover in the economic conditions thus created the means of ending the conflict". Critics have argued that utopian socialists who established experimental communities were in fact trying to apply the scientific method to human social organization and were therefore not utopian. On the basis of Karl Popper's definition of science as "the practice of experimentation, of hypothesis and test", Joshua Muravchik argued that "Owen and Fourier and their followers were the real 'scientific socialists.' They hit upon the idea of socialism, and they tested it by attempting to form socialist communities". By contrast, Muravchik further argued that Marx made untestable predictions about the future and that Marx's view that socialism would be created by impersonal historical forces may lead one to conclude that it is unnecessary to strive for socialism because it will happen anyway.[9]

Since the mid-19th century, Marxism and Marxism–Leninism overtook utopian socialism in terms of intellectual development and number of adherents. At one time almost half the population of the world lived under regimes that claimed to be Marxist.[10] Currents such as Saint-Simonianism and Fourierism attracted the interest of numerous later authors but failed to compete with the now dominant Marxist, Proudhonist, or Leninist schools on a political level. It has been noted that they exerted a significant influence on the emergence of new religious movements such as spiritualism and occultism.[11][12]

In literature and in practice

Perhaps the first utopian socialist was Thomas More (1478–1535), who wrote about an imaginary socialist society in his book Utopia, published in 1516. The contemporary definition of the English word utopia derives from this work and many aspects of More's description of Utopia were influenced by life in monasteries.[13]

Saint-Simonianism was a French political and social movement of the first half of the 19th century, inspired by the ideas of Henri de Saint-Simon (1760–1825). His ideas influenced Auguste Comte (who was for a time Saint-Simon's secretary), Karl Marx, John Stuart Mill and many other thinkers and social theorists.

Robert Owen was one of the founders of utopian socialism

Robert Owen (1771–1858) was a successful Welsh businessman who devoted much of his profits to improving the lives of his employees. His reputation grew when he set up a textile factory in New Lanark, Scotland, co-funded by his teacher, the utilitarian Jeremy Bentham and introduced shorter working hours, schools for children and renovated housing. He wrote about his ideas in his book A New View of Society which was published in 1813 and An Explanation of the Cause of Distress which pervades the civilized parts of the world in 1823. He also set up an Owenite commune called New Harmony in Indiana. This collapsed when one of his business partners ran off with all the profits. Owen's main contribution to socialist thought was the view that human social behavior is not fixed or absolute and that humans have the free will to organize themselves into any kind of society they wished.

Charles Fourier (1772–1837) rejected the Industrial Revolution altogether and thus the problems that arose with it. Fourier made various fanciful claims about the ideal world he envisioned. Despite some clearly non-socialist inclinations,[clarification needed] he contributed significantly even if indirectly to the socialist movement. His writings about turning work into play influenced the young Karl Marx and helped him devise his theory of alienation. Also a contributor to feminism, Fourier invented the concept of phalanstère, units of people based on a theory of passions and of their combination. Several colonies based on Fourier's ideas were founded in the United States by Albert Brisbane and Horace Greeley.

Many Romantic authors, most notably William Godwin and Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote anti-capitalist works and supported peasant revolutions across early 19th century Europe. Étienne Cabet (1788–1856), influenced by Robert Owen, published a book in 1840 entitled Travel and adventures of Lord William Carisdall in Icaria in which he described an ideal communalist society. His attempts to form real socialist communities based on his ideas through the Icarian movement did not survive, but one such community was the precursor of Corning, Iowa. Possibly inspired by Christianity, he coined the word communism and influenced other thinkers, including Marx and Engels.

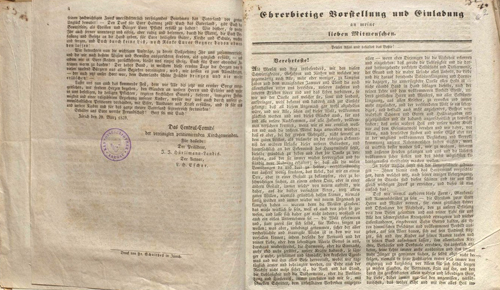

Utopian socialist pamphlet of Swiss social medical doctor Rudolf Sutermeister (1802–1868)

Edward Bellamy (1850–1898) published Looking Backward in 1888, a utopian romance novel about a future socialist society. In Bellamy's utopia, property was held in common and money replaced with a system of equal credit for all. Valid for a year and non-transferable between individuals, credit expenditure was to be tracked via "credit-cards" (which bear no resemblance to modern credit cards which are tools of debt-finance). Labour was compulsory from age 21 to 40 and organised via various departments of an Industrial Army to which most citizens belonged. Working hours were to be cut drastically due to technological advances (including organisational). People were expected to be motivated by a Religion of Solidarity and criminal behavior was treated as a form of mental illness or "atavism". The book ranked as second or third best seller of its time (after Uncle Tom's Cabin and Ben Hur). In 1897, Bellamy published a sequel entitled Equality as a reply to his critics and which lacked the Industrial Army and other authoritarian aspects.

William Morris (1834–1896) published News from Nowhere in 1890, partly as a response to Bellamy's Looking Backwards, which he equated with the socialism of Fabians such as Sydney Webb. Morris' vision of the future socialist society was centred around his concept of useful work as opposed to useless toil and the redemption of human labour. Morris believed that all work should be artistic, in the sense that the worker should find it both pleasurable and an outlet for creativity. Morris' conception of labour thus bears strong resemblance to Fourier's, while Bellamy's (the reduction of labour) is more akin to that of Saint-Simon or in aspects Marx.

The Brotherhood Church in Britain and the Life and Labor Commune in Russia were based on the Christian anarchist ideas of Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910).

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809–1865) and Peter Kropotkin (1842–1921) wrote about anarchist forms of socialism in their books. Proudhon wrote What is Property? (1840) and The System of Economic Contradictions, or The Philosophy of Poverty (1847). Kropotkin wrote The Conquest of Bread (1892) and Fields, Factories and Workshops (1912). Many of the anarchist collectives formed in Spain, especially in Aragon and Catalonia, during the Spanish Civil War were based on their ideas. While linking to different topics is always useful to maximize exposure, anarchism does not derive itself from utopian socialism and most anarchists would consider the association to essentially be a marxist slur designed to reduce the credibility of anarchism amongst socialists.[14]

Many participants in the historical kibbutz movement in Israel were motivated by utopian socialist ideas.[15]

Augustin Souchy (1892–1984) spent most of his life investigating and participating in many kinds of socialist communities. Souchy wrote about his experiences in his autobiography Beware! Anarchist!

Behavioral psychologist B. F. Skinner (1904–1990) published Walden Two in 1948. The Twin Oaks Community was originally based on his ideas.

Ursula K. Le Guin (1929-2018) wrote about an impoverished anarchist society in her book The Dispossessed, published in 1974, in which the anarchists agree to leave their home planet and colonize a barely habitable moon in order to avoid a bloody revolution.

Related concepts

Some communities of the modern intentional community movement such as kibbutzim could be categorized as utopian socialist.

Some religious communities such as the Hutterites are categorized as utopian religious socialists.[16]

Classless modes of production in hunter-gatherer societies are referred to as primitive communism by Marxists to stress their classless nature.[17]

A related concept is that of a socialist utopia, usually depicted in works of fiction as possible ways society can turn out to be in the future and often combined with notions of a technologically revolutionized economy.

Notable utopian socialists

• Edward Bellamy

• Tommaso Campanella

• Etienne Cabet

o Icarians

• Victor Considérant

• David Dale

• Charles Fourier

o North American Phalanx

o The Phalanx

• Henry George

• Jean-Baptiste Godin

• Laurence Gronlund

• Matti Kurikka

• John Lennon

• Thomas Moore

• John Humphrey Noyes

• Robert Owen

• Vaso Pelagić

• Henri de Saint-Simon

• William Thompson

• Wilhelm Weitling

• Gerrard Winstanley

Notable utopian communities

Utopian communities have existed all over the world. In various forms and locations, they have existed continuously in the United States since the 1730s, beginning with Ephrata Cloister, a religious community in what is now Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.[18]

Owenite communities

• New Lanark

• New Harmony, Indiana

Fourierist communities

• Brook Farm

• La Reunion (Dallas)

• North American Phalanx

• Silkville

• Utopia, Ohio

Icarian communities

• Corning, Iowa

Anarchist communities

• Home, Washington

• Life and Labor Commune

• Socialist Community of Modern Times

• Whiteway Colony

Others

• Kaweah Colony

• Llano del Rio

• Los Mochis

• Nevada City, Nevada

• New Australia

• Oneida Community

• Ruskin Colony

• Rugby, Tennessee

• Sointula

See also

• Christian socialism

• Communist utopia

• Diggers

• Ethical socialism

• Futurism

• History of socialism

• Ideal (ethics)

• Intentional communities

• Kibbutz

• List of anarchist communities

• Marxism

• Nanosocialism

• Post-capitalism

• Post-scarcity

• Ricardian socialism

• Scientific socialism

• Socialism

• Socialist economics

• Syndicalism

• Utopia for Realists

• Yellow socialism

• Zero waste

References

1. "Heaven on Earth: The Rise and Fall of Socialism". Public Broadcasting System. Retrieved December 15, 2011.

2. "Utopian socialism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

3. Draper, Hal (1990). Karl Marx's Theory of Revolution, Volume IV: Critique of Other Socialisms. New York: Monthly Review Press. pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-0853457985.

4. Newman, Michael. (2005) Socialism: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-

19-280431-6.

5. Thompson, Noel W. (2006). Political Economy and the Labour Party: The Economics of Democratic Socialism, 1884–2005 (2nd ed.). Abingdon, England: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-32880-7.

6. Frederick Engels. "Socialism: Utopian and Scientific (Chpt. 1)". Marxists.org. Retrieved July 3,2013.

7. Engels, Friedrich and Marx, Karl Heinrich. Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei. Edited by Sálvio M. Soares. MetaLibri, October 31, 2008, v1.0s.

8. Leopold, David (2018). "Marx, Engels and Some (Non-Foundational) Arguments Against Utopian Socialism". In Kandiyali, Jan (ed.). Reassessing Marx's Social and Political Philosophy: Freedom, Recognition and Human Flourishing. Routledge. p. 73.

9. Muravchik, Joshua (8 February 1999). "The Rise and Fall of Socialism". Bradley Lecture Series. American Enterprise Institute. Archived 3 May 1999 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

10. Steven Kreis (January 30, 2008). "Karl Marx, 1818-1883". The History Guide.

11. Strube, Julian (2016). "Socialist religion and the emergence of occultism: a genealogical approach to socialism and secularization in 19th-century France". Religion. 46 (3): 359–388. doi:10.1080/0048721X.2016.1146926.

12. Cyranka, Daniel (2016). "Religious Revolutionaries and Spiritualism in Germany around 1848". Aries. 16 (1): 13–48. doi:10.1163/15700593-01601002.

13. J. C. Davis (28 July 1983). Utopia and the Ideal Society: A Study of English Utopian Writing 1516-1700. Cambridge University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-521-27551-4.

14. Sam Dolgoff (1990). The Anarchist Collectives: Workers' Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939. Black Rose Books.

15. Sheldon Goldenberg and Gerda R. Wekerle (September 1972). "From utopia to total institution in a single generation: the kibbutz and Bruderhof". International Review of Modern Sociology. 2 (2): 224–232. JSTOR 41420450.

16. Donald E. Frey (2009). America's Economic Moralists: A History of Rival Ethics and Economics. SUNY Press. p. 61. ISBN 9780791493663.

17. "Primitive communism: life before class and oppression". Socialist Worker. May 28, 2013. Retrieved December 27, 2019.

18. Yaacov Oved (1988). Two Hundred Years of American Communes. Transaction Publishers. pp. 3, 19.

Further reading[edit]

• Taylor, Keith (1992). The political ideas of Utopian socialists. London: Cass. ISBN 0714630896.

External links

• Media related to Utopian socialism at Wikimedia Commons

• Be Utopian: Demand the Realistic by Robert Pollin, The Nation, March 9, 2009.

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/26/20

Utopian socialism is the first current of modern socialism and socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, Étienne Cabet,...

Étienne Cabet (French: [kabɛ]; January 1, 1788 – November 9, 1856) was a French philosopher and utopian socialist who founded the Icarian movement. Cabet became the most popular socialist advocate of his day, with a special appeal to artisans who were being undercut by factories. Cabet published Voyage en Icarie in French in 1839 (and in English in 1840 as Travels in Icaria), in which he proposed replacing capitalist production with workers' cooperatives. Recurrent problems with French officials (a treason conviction in 1834 resulted in five years' exile in England), led him to emigrate to the United States in 1848. Cabet founded utopian communities in Texas and Illinois, but was again undercut, this time by recurring feuds with his followers.

-- Étienne Cabet, by Wikipedia

Robert Owen and Henry George.[1][2] Utopian socialism is often described as the presentation of visions and outlines for imaginary or futuristic ideal societies, with positive ideals being the main reason for moving society in such a direction. Later socialists and critics of utopian socialism viewed utopian socialism as not being grounded in actual material conditions of existing society and in some cases as reactionary. These visions of ideal societies competed with Marxist-inspired revolutionary social democratic movements.[3]

As a term or label, utopian socialism is most often applied to, or used to define, those socialists who lived in the first quarter of the 19th century who were ascribed the label utopian by later socialists as a pejorative in order to imply naiveté and to dismiss their ideas as fanciful and unrealistic.[4] A similar school of thought that emerged in the early 20th century which makes the case for socialism on moral grounds is ethical socialism.[5]

One key difference between utopian socialists and other socialists such as most anarchists and Marxists is that utopian socialists generally do not believe any form of class struggle or social revolution is necessary for socialism to emerge. Utopian socialists believe that people of all classes can voluntarily adopt their plan for society if it is presented convincingly.[3] They feel their form of cooperative socialism can be established among like-minded people within the existing society and that their small communities can demonstrate the feasibility of their plan for society.[3]

Definition

See also: Utopia

The thinkers identified as utopian socialist did not use the term utopian to refer to their ideas. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels were the first thinkers to refer to them as utopian, referring to all socialist ideas that simply presented a vision and distant goal of an ethically just society as utopian. This utopian mindset which held an integrated conception of the goal, the means to produce said goal and an understanding of the way that those means would inevitably be produced through examining social and economic phenomena can be contrasted with scientific socialism which has been likened to Taylorism.[citation needed]

This distinction was made clear in Engels' work Socialism: Utopian and Scientific (1892, part of an earlier publication, the Anti-Dühring from 1878). Utopian socialists were seen as wanting to expand the principles of the French revolution in order to create a more rational society. Despite being labeled as utopian by later socialists, their aims were not always utopian and their values often included rigid support for the scientific method and the creation of a society based upon scientific understanding.[6]

Development

The term utopian socialism was introduced by Karl Marx in "For a Ruthless Criticism of Everything" in 1843 and then developed in The Communist Manifesto in 1848, although shortly before its publication Marx had already attacked the ideas of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in The Poverty of Philosophy (originally written in French, 1847). The term was used by later socialist thinkers to describe early socialist or quasi-socialist intellectuals who created hypothetical visions of egalitarian, communalist, meritocratic, or other notions of perfect societies without considering how these societies could be created or sustained.

In The Poverty of Philosophy, Marx criticized the economic and philosophical arguments of Proudhon set forth in The System of Economic Contradictions, or The Philosophy of Poverty. Marx accused Proudhon of wanting to rise above the bourgeoisie. In the history of Marx's thought and Marxism, this work is pivotal in the distinction between the concepts of utopian socialism and what Marx and the Marxists claimed as scientific socialism. Although utopian socialists shared few political, social, or economic perspectives, Marx and Engels argued that they shared certain intellectual characteristics. In The Communist Manifesto, Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote: "The undeveloped state of the class struggle, as well as their own surroundings, causes Socialists of this kind to consider themselves far superior to all class antagonisms. They want to improve the condition of every member of society, even that of the most favored. Hence, they habitually appeal to society at large, without distinction of class; nay, by preference, to the ruling class. For how can people, when once they understand their system, fail to see it in the best possible plan of the best possible state of society? Hence, they reject all political, and especially all revolutionary, action; they wish to attain their ends by peaceful means, and endeavor, by small experiments, necessarily doomed to failure, and by the force of example, to pave the way for the new social Gospel".[7]

Marx and Engels associated utopian socialism with communitarian socialism which similarly sees the establishment of small intentional communities as both a strategy for achieving and the final form of a socialist society.[8] Marx and Engels used the term scientific socialism to describe the type of socialism they saw themselves developing. According to Engels, socialism was not "an accidental discovery of this or that ingenious brain, but the necessary outcome of the struggle between two historically developed classes, namely the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. Its task was no longer to manufacture a system of society as perfect as possible, but to examine the historical-economic succession of events from which these classes and their antagonism had of necessity sprung, and to discover in the economic conditions thus created the means of ending the conflict". Critics have argued that utopian socialists who established experimental communities were in fact trying to apply the scientific method to human social organization and were therefore not utopian. On the basis of Karl Popper's definition of science as "the practice of experimentation, of hypothesis and test", Joshua Muravchik argued that "Owen and Fourier and their followers were the real 'scientific socialists.' They hit upon the idea of socialism, and they tested it by attempting to form socialist communities". By contrast, Muravchik further argued that Marx made untestable predictions about the future and that Marx's view that socialism would be created by impersonal historical forces may lead one to conclude that it is unnecessary to strive for socialism because it will happen anyway.[9]

Since the mid-19th century, Marxism and Marxism–Leninism overtook utopian socialism in terms of intellectual development and number of adherents. At one time almost half the population of the world lived under regimes that claimed to be Marxist.[10] Currents such as Saint-Simonianism and Fourierism attracted the interest of numerous later authors but failed to compete with the now dominant Marxist, Proudhonist, or Leninist schools on a political level. It has been noted that they exerted a significant influence on the emergence of new religious movements such as spiritualism and occultism.[11][12]

In literature and in practice

Perhaps the first utopian socialist was Thomas More (1478–1535), who wrote about an imaginary socialist society in his book Utopia, published in 1516. The contemporary definition of the English word utopia derives from this work and many aspects of More's description of Utopia were influenced by life in monasteries.[13]

Saint-Simonianism was a French political and social movement of the first half of the 19th century, inspired by the ideas of Henri de Saint-Simon (1760–1825). His ideas influenced Auguste Comte (who was for a time Saint-Simon's secretary), Karl Marx, John Stuart Mill and many other thinkers and social theorists.

Robert Owen was one of the founders of utopian socialism

Robert Owen (1771–1858) was a successful Welsh businessman who devoted much of his profits to improving the lives of his employees. His reputation grew when he set up a textile factory in New Lanark, Scotland, co-funded by his teacher, the utilitarian Jeremy Bentham and introduced shorter working hours, schools for children and renovated housing. He wrote about his ideas in his book A New View of Society which was published in 1813 and An Explanation of the Cause of Distress which pervades the civilized parts of the world in 1823. He also set up an Owenite commune called New Harmony in Indiana. This collapsed when one of his business partners ran off with all the profits. Owen's main contribution to socialist thought was the view that human social behavior is not fixed or absolute and that humans have the free will to organize themselves into any kind of society they wished.

Charles Fourier (1772–1837) rejected the Industrial Revolution altogether and thus the problems that arose with it. Fourier made various fanciful claims about the ideal world he envisioned. Despite some clearly non-socialist inclinations,[clarification needed] he contributed significantly even if indirectly to the socialist movement. His writings about turning work into play influenced the young Karl Marx and helped him devise his theory of alienation. Also a contributor to feminism, Fourier invented the concept of phalanstère, units of people based on a theory of passions and of their combination. Several colonies based on Fourier's ideas were founded in the United States by Albert Brisbane and Horace Greeley.

Many Romantic authors, most notably William Godwin and Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote anti-capitalist works and supported peasant revolutions across early 19th century Europe. Étienne Cabet (1788–1856), influenced by Robert Owen, published a book in 1840 entitled Travel and adventures of Lord William Carisdall in Icaria in which he described an ideal communalist society. His attempts to form real socialist communities based on his ideas through the Icarian movement did not survive, but one such community was the precursor of Corning, Iowa. Possibly inspired by Christianity, he coined the word communism and influenced other thinkers, including Marx and Engels.

Utopian socialist pamphlet of Swiss social medical doctor Rudolf Sutermeister (1802–1868)

Edward Bellamy (1850–1898) published Looking Backward in 1888, a utopian romance novel about a future socialist society. In Bellamy's utopia, property was held in common and money replaced with a system of equal credit for all. Valid for a year and non-transferable between individuals, credit expenditure was to be tracked via "credit-cards" (which bear no resemblance to modern credit cards which are tools of debt-finance). Labour was compulsory from age 21 to 40 and organised via various departments of an Industrial Army to which most citizens belonged. Working hours were to be cut drastically due to technological advances (including organisational). People were expected to be motivated by a Religion of Solidarity and criminal behavior was treated as a form of mental illness or "atavism". The book ranked as second or third best seller of its time (after Uncle Tom's Cabin and Ben Hur). In 1897, Bellamy published a sequel entitled Equality as a reply to his critics and which lacked the Industrial Army and other authoritarian aspects.

William Morris (1834–1896) published News from Nowhere in 1890, partly as a response to Bellamy's Looking Backwards, which he equated with the socialism of Fabians such as Sydney Webb. Morris' vision of the future socialist society was centred around his concept of useful work as opposed to useless toil and the redemption of human labour. Morris believed that all work should be artistic, in the sense that the worker should find it both pleasurable and an outlet for creativity. Morris' conception of labour thus bears strong resemblance to Fourier's, while Bellamy's (the reduction of labour) is more akin to that of Saint-Simon or in aspects Marx.

The Brotherhood Church in Britain and the Life and Labor Commune in Russia were based on the Christian anarchist ideas of Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910).

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809–1865) and Peter Kropotkin (1842–1921) wrote about anarchist forms of socialism in their books. Proudhon wrote What is Property? (1840) and The System of Economic Contradictions, or The Philosophy of Poverty (1847). Kropotkin wrote The Conquest of Bread (1892) and Fields, Factories and Workshops (1912). Many of the anarchist collectives formed in Spain, especially in Aragon and Catalonia, during the Spanish Civil War were based on their ideas. While linking to different topics is always useful to maximize exposure, anarchism does not derive itself from utopian socialism and most anarchists would consider the association to essentially be a marxist slur designed to reduce the credibility of anarchism amongst socialists.[14]

Many participants in the historical kibbutz movement in Israel were motivated by utopian socialist ideas.[15]

Augustin Souchy (1892–1984) spent most of his life investigating and participating in many kinds of socialist communities. Souchy wrote about his experiences in his autobiography Beware! Anarchist!

Behavioral psychologist B. F. Skinner (1904–1990) published Walden Two in 1948. The Twin Oaks Community was originally based on his ideas.

Ursula K. Le Guin (1929-2018) wrote about an impoverished anarchist society in her book The Dispossessed, published in 1974, in which the anarchists agree to leave their home planet and colonize a barely habitable moon in order to avoid a bloody revolution.

Related concepts

Some communities of the modern intentional community movement such as kibbutzim could be categorized as utopian socialist.

Some religious communities such as the Hutterites are categorized as utopian religious socialists.[16]

Classless modes of production in hunter-gatherer societies are referred to as primitive communism by Marxists to stress their classless nature.[17]

A related concept is that of a socialist utopia, usually depicted in works of fiction as possible ways society can turn out to be in the future and often combined with notions of a technologically revolutionized economy.

Notable utopian socialists

• Edward Bellamy

• Tommaso Campanella

• Etienne Cabet

o Icarians

• Victor Considérant

• David Dale

• Charles Fourier

o North American Phalanx

o The Phalanx

• Henry George

• Jean-Baptiste Godin

• Laurence Gronlund

• Matti Kurikka

• John Lennon

• Thomas Moore

• John Humphrey Noyes

• Robert Owen

• Vaso Pelagić

• Henri de Saint-Simon

• William Thompson

• Wilhelm Weitling

• Gerrard Winstanley

Notable utopian communities

Utopian communities have existed all over the world. In various forms and locations, they have existed continuously in the United States since the 1730s, beginning with Ephrata Cloister, a religious community in what is now Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.[18]

Owenite communities

• New Lanark

• New Harmony, Indiana

Fourierist communities

• Brook Farm

• La Reunion (Dallas)

• North American Phalanx

• Silkville

• Utopia, Ohio

Icarian communities

• Corning, Iowa

Anarchist communities

• Home, Washington

• Life and Labor Commune

• Socialist Community of Modern Times

• Whiteway Colony

Others

• Kaweah Colony

• Llano del Rio

• Los Mochis

• Nevada City, Nevada

• New Australia

• Oneida Community

• Ruskin Colony

• Rugby, Tennessee

• Sointula

See also

• Christian socialism

• Communist utopia

• Diggers

• Ethical socialism

• Futurism

• History of socialism

• Ideal (ethics)

• Intentional communities

• Kibbutz

• List of anarchist communities

• Marxism

• Nanosocialism

• Post-capitalism

• Post-scarcity

• Ricardian socialism

• Scientific socialism

• Socialism

• Socialist economics

• Syndicalism

• Utopia for Realists

• Yellow socialism

• Zero waste

References

1. "Heaven on Earth: The Rise and Fall of Socialism". Public Broadcasting System. Retrieved December 15, 2011.

2. "Utopian socialism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

3. Draper, Hal (1990). Karl Marx's Theory of Revolution, Volume IV: Critique of Other Socialisms. New York: Monthly Review Press. pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-0853457985.

4. Newman, Michael. (2005) Socialism: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-

19-280431-6.

5. Thompson, Noel W. (2006). Political Economy and the Labour Party: The Economics of Democratic Socialism, 1884–2005 (2nd ed.). Abingdon, England: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-32880-7.

6. Frederick Engels. "Socialism: Utopian and Scientific (Chpt. 1)". Marxists.org. Retrieved July 3,2013.

7. Engels, Friedrich and Marx, Karl Heinrich. Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei. Edited by Sálvio M. Soares. MetaLibri, October 31, 2008, v1.0s.

8. Leopold, David (2018). "Marx, Engels and Some (Non-Foundational) Arguments Against Utopian Socialism". In Kandiyali, Jan (ed.). Reassessing Marx's Social and Political Philosophy: Freedom, Recognition and Human Flourishing. Routledge. p. 73.

9. Muravchik, Joshua (8 February 1999). "The Rise and Fall of Socialism". Bradley Lecture Series. American Enterprise Institute. Archived 3 May 1999 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

10. Steven Kreis (January 30, 2008). "Karl Marx, 1818-1883". The History Guide.

11. Strube, Julian (2016). "Socialist religion and the emergence of occultism: a genealogical approach to socialism and secularization in 19th-century France". Religion. 46 (3): 359–388. doi:10.1080/0048721X.2016.1146926.

12. Cyranka, Daniel (2016). "Religious Revolutionaries and Spiritualism in Germany around 1848". Aries. 16 (1): 13–48. doi:10.1163/15700593-01601002.

13. J. C. Davis (28 July 1983). Utopia and the Ideal Society: A Study of English Utopian Writing 1516-1700. Cambridge University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-521-27551-4.

14. Sam Dolgoff (1990). The Anarchist Collectives: Workers' Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939. Black Rose Books.

15. Sheldon Goldenberg and Gerda R. Wekerle (September 1972). "From utopia to total institution in a single generation: the kibbutz and Bruderhof". International Review of Modern Sociology. 2 (2): 224–232. JSTOR 41420450.

16. Donald E. Frey (2009). America's Economic Moralists: A History of Rival Ethics and Economics. SUNY Press. p. 61. ISBN 9780791493663.

17. "Primitive communism: life before class and oppression". Socialist Worker. May 28, 2013. Retrieved December 27, 2019.

18. Yaacov Oved (1988). Two Hundred Years of American Communes. Transaction Publishers. pp. 3, 19.

Further reading[edit]

• Taylor, Keith (1992). The political ideas of Utopian socialists. London: Cass. ISBN 0714630896.

External links

• Media related to Utopian socialism at Wikimedia Commons

• Be Utopian: Demand the Realistic by Robert Pollin, The Nation, March 9, 2009.

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 40037

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

Étienne Cabet

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/26/20

Étienne Cabet

Born: January 1, 1788, Dijon, Côte-d'Or

Died: November 9, 1856 (aged 68), St. Louis, Missouri, United States

Occupation: philosopher

Known for: founder of the Icarian movement

Notable work: "Travel and Adventures of Lord William Carisdall in Icaria" (1840)

Étienne Cabet (French: [kabɛ]; January 1, 1788 – November 9, 1856) was a French philosopher and utopian socialist who founded the Icarian movement. Cabet became the most popular socialist advocate of his day, with a special appeal to artisans who were being undercut by factories. Cabet published Voyage en Icarie in French in 1839 (and in English in 1840 as Travels in Icaria), in which he proposed replacing capitalist production with workers' cooperatives. Recurrent problems with French officials (a treason conviction in 1834 resulted in five years' exile in England), led him to emigrate to the United States in 1848. Cabet founded utopian communities in Texas and Illinois, but was again undercut, this time by recurring feuds with his followers.

Early and family life

Cabet was born in Dijon, Côte-d'Or, the youngest son of a cooper from Burgundy, Claude Cabet, and his wife Francoise Berthier. He was educated as a lawyer.[1] Cabet married Delphine Lasage on March 25, 1839 at Marylebone, London, during his exile in England, who bore a child.[2][3]

Career in France

Cabet secured an appointment as attorney-general in Corsica. He represented the government of Louis Philippe, despite having headed an insurrectionary committee during the July Revolution of 1830 which led to the ouster of the "Republican Monarch" King Charles X (and the ascent of Louis Philippe). However, Cabet lost this position for his attack upon the conservatism of the government in his Histoire de la révolution de 1830.[4] Nonetheless, in 1831, Cabet was elected to the Chamber of Deputies in France as the representative of Côte d'Or, and sat with the extreme radicals.[5] Accused of treason in 1834 because of his bitter attacks on the government both in the history book and subsequently, Cabet was convicted and sentenced to five years' exile.[6] He fled to England and sought political asylum. Influenced by Robert Owen, Thomas More and Charles Fourier, Cabet wrote Voyage et aventures de lord William Carisdall en Icarie ("Travel and Adventures of Lord William Carisdall in Icaria", 1840), which depicted a utopia in which a democratically elected governing body controlled all economic activity and closely supervised social life. "Icaria" is the name of his fictional country and ideal society. The nuclear family remained the only other independent unit. The book's success prompted Cabet to take steps to realize his Utopia.[5]

In 1839, Cabet returned to France to advocate a communitarian social movement, for which he invented the term communisme.[7] Some writers ignored Cabet's Christian influences, as described in his book Le vrai christianisme suivant Jésus Christ ("The real Christianity according to Jesus Christ", in five volumes, 1846). This book described Christ's mission to be to establish social equality, and contrasted primitive Christianity with the ecclesiasticism of Cabet's time to the disparagement of the latter. In it, Cabet argued that the kingdom of God announced by Jesus was nothing other than a communist society.[8] The book also contained a popular history of the French Revolutions from 1789 to 1830.[5]

In 1841 Cabet revived the Populaire (founded by him in 1833), which was widely read by French workingmen, and from 1843 to 1847 he printed an Icarian almanac, a number of controversial pamphlets as well as the above-mentioned book on Christianity. There were probably 400,000 adherents of the Icarian school.[5]

Emigration to the United States of America

In 1847, after realizing the economic hardship caused by the depression of 1846, Cabet gave up on the notion of reforming French society.[9] Instead, after conversations with Robert Owen and Owen's attempts to found a commune in Texas, Cabet gathered a group of followers from across France and traveled to the United States to organize an Icarian community.[10] They entered into a social contract, making Cabet the director-in-chief for the first ten years, and embarked from Le Havre, February 3, 1848, for New Orleans, Louisiana. They expected to settle in the Red River valley in Texas. However, the Peters Land Company gave them deeds to only 320 acres of land in Denton County, Texas near what became Dallas, Texas rather than the million acres of land in the Red River Valley they expected (more than 200 miles away).[9] The first group of emigrants ultimately returned to New Orleans; Cabet came later at the head of a second and smaller band. Neither Texas nor Louisiana proved the looked-for Utopia, and, ravaged by disease, about one-third of the colonists returned to France.[5]

The remainder (142 men, 74 women and 64 children, although 20 died of cholera en route), moved northward along the Mississippi River to Nauvoo, Illinois, where they purchased twelve acres recently vacated by the Mormons in 1849.[11][9] Cabet was unanimously elected leader, for a one-year term. The improved location enabled the experiment to develop into a successful agricultural community. Education and culture were highly valued by members. By 1855, the Nauvoo Icarian community had expanded to about 500 members with a solid agricultural base, as well as shops, three schools, flour and sawmills, a whiskey distillery, English and French newspapers, a 39 piece orchestra, choir, theater, hospital and the state's largest library (4000 volumes).[11] Members met on Saturdays to discuss community affairs and problems, with universal male suffrage; women were allowed to speak but not vote. On Sundays members talked about ethical and moral issues, but there were no denominational religious services, only members had espoused Christianity before joining the community. Based on this success, some even considered expanding the community 200 miles west to Adair County, Iowa.[12]

However, Cabet was forced to return to France in May 1851 to settle charges of fraud brought up by his previous followers in Europe.[11][13] Although found not guilty by a French jury in July 1851, when Cabet returned to Nauvoo in July 1852, the community had changed. Some men were using tobacco and abusing alcohol, many women were adorning themselves with fancy dresses and jewelry, and families claimed land as private property. Cabet responded by issuing "Forty-Eight Rules of Conduct" on November 23, 1853, forbidding "tobacco, hard liquor, complaints about the food, and hunting and fishing 'for pleasure'" as well as demanding absolute silence in workshops and submission to him.[13] Some described him as authoritarian or emotionally unstable; internal problems arose and worsened.[14]

In the spring of 1855, Cabet tried to revise the colony's constitution to make him president for life, but was instead relieved of the presidency, so his followers went out on strike, and were in turn temporarily barred from the communal dining hall.[14] Although the colony by then had 526 members and 57 more across the Mississippi River at Montrose, Iowa, it was suffering economically—dependent upon money brought by new members and subsidies from the "Le Populaire" home office in France.[13][14]

Moreover, split regarding the work division and food distribution worsened during the summer and following year.[11] Cabet published his final book, Colonie icarienne aux États-Unis d'Amérique (1856), but that failed to solve the internal problems. In October 1856, about 180 supporters and Cabet left Nauvoo in three groups for New Bremen, Missouri near St. Louis, Missouri.

Death and legacy

Cabet suffered a stroke on November 8, 1856, a few days after moving to Missouri with the last group of his followers, and soon died.[15] He was buried at the Old Picker's Cemetery, but his remains were moved during construction of a high school on the site, and now rest at New Saint Marcus Cemetery and Mausoleum in Affton, St. Louis County, Missouri, with a gravestone funded by the French Embassy.[2]

On February 15, 1858, the remaining Icarians settled in Cheltenham on the western edge of St. Louis, under the leadership of a lawyer named Mercadier, whom Cabet had designated as his successor. That colony would disband in 1864 (with several young men fighting in the American Civil War) and two families rejoined the Icarians in Corning, Iowa discussed below (the Cheltenham area became a neighborhood within St. Louis).[16] Before his death, Cabet sued the Nauvoo Icarians in a local court, as well as petitioned the Illinois legislature to repeal the act that incorporated the community.[11][17] The Nauvoo colony relocated to Corning, Adams County, Iowa, about 80 miles southwest of Des Moines, Iowa between 1858 and 1860, because of Illinois crop failures as well as the end of financial support from France following the Panic of 1857. The Corning Icarians prospered until another factional split in 1878, prompted by new emigrants from France, who left to establish a community in Cloverdale, California in 1883 (but "Icaria Speranza" lasted only four years). The colony at Corning disbanded in 1898, but by that time it had existed for 46 years, making it the longest non-religious communal living experiment in American history.[16]

The library at Western Illinois University has a Center for Icarian Studies, as well as Icarian archives and papers. The Nauvoo Historical Society also has some papers and artifacts on display, and some in the town remember the Icarians during the Labor Day Grape Festival, through a historical play. Although the growing of Concord grapes in the Nauvoo area began in the 1830s based on the efforts of a French Catholic priest and expanded in 1846 when a Swiss vintner named John Tanner brought the Norton grape to the area, Baxter's Vineyards and Winery (founded Icarians Emile and Annette Baxter in 1857) continues as a 5-generation old family business and is Illinois' oldest winery.[16]

References

1. Soland 2017, p. 57.

2. "Etienne Cabet (1788-1856) Find A Grave-herdenking".

3. British parish records on ancestry.com; the child may have been Gentilly Cabet, who married Eugene Dagousset in Paris in 1891 according to another ancestry.com database

4. Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cabet, Étienne" . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

5. Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Cabet, Etienne" . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

6. Soland 2017, p. 58.

7. "CABET, Etienne (1788-1856) Fondateur du communisme en France". Recherches sur l’anarchisme. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

8. Paul Bénichou, Le Sacre de l'écrivain : Doctrines de l'âge romantique (Paris: Gallimard, 1977), p. 402 n.63.

9. Soland 2017, p. 59.

10. Friesen, John W.; Friesen, Virginia Lyons (2004). The Palgrave Companion to North American Utopias. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 137.

11. Friesen, John W.; Friesen, Virginia Lyons (2004). The Palgrave Companion to North American Utopias. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 139.

12. Soland 2017, p. 63.

13. Pitzer, Donald (1997). America's Communal Utopias. Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press. p. 283.

14. Soland 2017, p. 64.

15. Ancestry.com's Missouri Registry of Deaths for the week of November 10, 1856, p. 122

16. Soland 2017, p. 65.

17. Some miscellaneous handwritten records of the Hancock County, Illinois court relative to "E. Cabbett" are available in ancestry.com's library edition, images 1117-1119 of 1825-1858 records

Further reading

• Johnson, Christopher H (1974). Utopian communism in France : Cabet and the Icarians, 1839-1851. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801408953. OCLC 1223569.

• Soland, Randall (2017). Utopian communities of Illinois : heaven on the prairie. Charleston, SC: History Press. ISBN 9781439661666. OCLC 1004538134.

• Sutton, Robert P. (1994). Les Icariens : the utopian dream in Europe and America. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252020674. OCLC 28215643.

External links

• Étienne Cabet from the Handbook of Texas Online

• Encyclopædia Britannica Etienne Cabet

• Archive of Etienne Cabet Papers at the International Institute of Social History

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/26/20

Étienne Cabet

Born: January 1, 1788, Dijon, Côte-d'Or

Died: November 9, 1856 (aged 68), St. Louis, Missouri, United States

Occupation: philosopher

Known for: founder of the Icarian movement

Notable work: "Travel and Adventures of Lord William Carisdall in Icaria" (1840)

Étienne Cabet (French: [kabɛ]; January 1, 1788 – November 9, 1856) was a French philosopher and utopian socialist who founded the Icarian movement. Cabet became the most popular socialist advocate of his day, with a special appeal to artisans who were being undercut by factories. Cabet published Voyage en Icarie in French in 1839 (and in English in 1840 as Travels in Icaria), in which he proposed replacing capitalist production with workers' cooperatives. Recurrent problems with French officials (a treason conviction in 1834 resulted in five years' exile in England), led him to emigrate to the United States in 1848. Cabet founded utopian communities in Texas and Illinois, but was again undercut, this time by recurring feuds with his followers.

Early and family life

Cabet was born in Dijon, Côte-d'Or, the youngest son of a cooper from Burgundy, Claude Cabet, and his wife Francoise Berthier. He was educated as a lawyer.[1] Cabet married Delphine Lasage on March 25, 1839 at Marylebone, London, during his exile in England, who bore a child.[2][3]

Career in France

Cabet secured an appointment as attorney-general in Corsica. He represented the government of Louis Philippe, despite having headed an insurrectionary committee during the July Revolution of 1830 which led to the ouster of the "Republican Monarch" King Charles X (and the ascent of Louis Philippe). However, Cabet lost this position for his attack upon the conservatism of the government in his Histoire de la révolution de 1830.[4] Nonetheless, in 1831, Cabet was elected to the Chamber of Deputies in France as the representative of Côte d'Or, and sat with the extreme radicals.[5] Accused of treason in 1834 because of his bitter attacks on the government both in the history book and subsequently, Cabet was convicted and sentenced to five years' exile.[6] He fled to England and sought political asylum. Influenced by Robert Owen, Thomas More and Charles Fourier, Cabet wrote Voyage et aventures de lord William Carisdall en Icarie ("Travel and Adventures of Lord William Carisdall in Icaria", 1840), which depicted a utopia in which a democratically elected governing body controlled all economic activity and closely supervised social life. "Icaria" is the name of his fictional country and ideal society. The nuclear family remained the only other independent unit. The book's success prompted Cabet to take steps to realize his Utopia.[5]

In 1839, Cabet returned to France to advocate a communitarian social movement, for which he invented the term communisme.[7] Some writers ignored Cabet's Christian influences, as described in his book Le vrai christianisme suivant Jésus Christ ("The real Christianity according to Jesus Christ", in five volumes, 1846). This book described Christ's mission to be to establish social equality, and contrasted primitive Christianity with the ecclesiasticism of Cabet's time to the disparagement of the latter. In it, Cabet argued that the kingdom of God announced by Jesus was nothing other than a communist society.[8] The book also contained a popular history of the French Revolutions from 1789 to 1830.[5]

In 1841 Cabet revived the Populaire (founded by him in 1833), which was widely read by French workingmen, and from 1843 to 1847 he printed an Icarian almanac, a number of controversial pamphlets as well as the above-mentioned book on Christianity. There were probably 400,000 adherents of the Icarian school.[5]

Emigration to the United States of America

In 1847, after realizing the economic hardship caused by the depression of 1846, Cabet gave up on the notion of reforming French society.[9] Instead, after conversations with Robert Owen and Owen's attempts to found a commune in Texas, Cabet gathered a group of followers from across France and traveled to the United States to organize an Icarian community.[10] They entered into a social contract, making Cabet the director-in-chief for the first ten years, and embarked from Le Havre, February 3, 1848, for New Orleans, Louisiana. They expected to settle in the Red River valley in Texas. However, the Peters Land Company gave them deeds to only 320 acres of land in Denton County, Texas near what became Dallas, Texas rather than the million acres of land in the Red River Valley they expected (more than 200 miles away).[9] The first group of emigrants ultimately returned to New Orleans; Cabet came later at the head of a second and smaller band. Neither Texas nor Louisiana proved the looked-for Utopia, and, ravaged by disease, about one-third of the colonists returned to France.[5]

The remainder (142 men, 74 women and 64 children, although 20 died of cholera en route), moved northward along the Mississippi River to Nauvoo, Illinois, where they purchased twelve acres recently vacated by the Mormons in 1849.[11][9] Cabet was unanimously elected leader, for a one-year term. The improved location enabled the experiment to develop into a successful agricultural community. Education and culture were highly valued by members. By 1855, the Nauvoo Icarian community had expanded to about 500 members with a solid agricultural base, as well as shops, three schools, flour and sawmills, a whiskey distillery, English and French newspapers, a 39 piece orchestra, choir, theater, hospital and the state's largest library (4000 volumes).[11] Members met on Saturdays to discuss community affairs and problems, with universal male suffrage; women were allowed to speak but not vote. On Sundays members talked about ethical and moral issues, but there were no denominational religious services, only members had espoused Christianity before joining the community. Based on this success, some even considered expanding the community 200 miles west to Adair County, Iowa.[12]

However, Cabet was forced to return to France in May 1851 to settle charges of fraud brought up by his previous followers in Europe.[11][13] Although found not guilty by a French jury in July 1851, when Cabet returned to Nauvoo in July 1852, the community had changed. Some men were using tobacco and abusing alcohol, many women were adorning themselves with fancy dresses and jewelry, and families claimed land as private property. Cabet responded by issuing "Forty-Eight Rules of Conduct" on November 23, 1853, forbidding "tobacco, hard liquor, complaints about the food, and hunting and fishing 'for pleasure'" as well as demanding absolute silence in workshops and submission to him.[13] Some described him as authoritarian or emotionally unstable; internal problems arose and worsened.[14]

In the spring of 1855, Cabet tried to revise the colony's constitution to make him president for life, but was instead relieved of the presidency, so his followers went out on strike, and were in turn temporarily barred from the communal dining hall.[14] Although the colony by then had 526 members and 57 more across the Mississippi River at Montrose, Iowa, it was suffering economically—dependent upon money brought by new members and subsidies from the "Le Populaire" home office in France.[13][14]

Moreover, split regarding the work division and food distribution worsened during the summer and following year.[11] Cabet published his final book, Colonie icarienne aux États-Unis d'Amérique (1856), but that failed to solve the internal problems. In October 1856, about 180 supporters and Cabet left Nauvoo in three groups for New Bremen, Missouri near St. Louis, Missouri.

Death and legacy

Cabet suffered a stroke on November 8, 1856, a few days after moving to Missouri with the last group of his followers, and soon died.[15] He was buried at the Old Picker's Cemetery, but his remains were moved during construction of a high school on the site, and now rest at New Saint Marcus Cemetery and Mausoleum in Affton, St. Louis County, Missouri, with a gravestone funded by the French Embassy.[2]

On February 15, 1858, the remaining Icarians settled in Cheltenham on the western edge of St. Louis, under the leadership of a lawyer named Mercadier, whom Cabet had designated as his successor. That colony would disband in 1864 (with several young men fighting in the American Civil War) and two families rejoined the Icarians in Corning, Iowa discussed below (the Cheltenham area became a neighborhood within St. Louis).[16] Before his death, Cabet sued the Nauvoo Icarians in a local court, as well as petitioned the Illinois legislature to repeal the act that incorporated the community.[11][17] The Nauvoo colony relocated to Corning, Adams County, Iowa, about 80 miles southwest of Des Moines, Iowa between 1858 and 1860, because of Illinois crop failures as well as the end of financial support from France following the Panic of 1857. The Corning Icarians prospered until another factional split in 1878, prompted by new emigrants from France, who left to establish a community in Cloverdale, California in 1883 (but "Icaria Speranza" lasted only four years). The colony at Corning disbanded in 1898, but by that time it had existed for 46 years, making it the longest non-religious communal living experiment in American history.[16]

The library at Western Illinois University has a Center for Icarian Studies, as well as Icarian archives and papers. The Nauvoo Historical Society also has some papers and artifacts on display, and some in the town remember the Icarians during the Labor Day Grape Festival, through a historical play. Although the growing of Concord grapes in the Nauvoo area began in the 1830s based on the efforts of a French Catholic priest and expanded in 1846 when a Swiss vintner named John Tanner brought the Norton grape to the area, Baxter's Vineyards and Winery (founded Icarians Emile and Annette Baxter in 1857) continues as a 5-generation old family business and is Illinois' oldest winery.[16]

References

1. Soland 2017, p. 57.

2. "Etienne Cabet (1788-1856) Find A Grave-herdenking".

3. British parish records on ancestry.com; the child may have been Gentilly Cabet, who married Eugene Dagousset in Paris in 1891 according to another ancestry.com database

4. Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cabet, Étienne" . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

5. Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Cabet, Etienne" . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

6. Soland 2017, p. 58.

7. "CABET, Etienne (1788-1856) Fondateur du communisme en France". Recherches sur l’anarchisme. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

8. Paul Bénichou, Le Sacre de l'écrivain : Doctrines de l'âge romantique (Paris: Gallimard, 1977), p. 402 n.63.

9. Soland 2017, p. 59.

10. Friesen, John W.; Friesen, Virginia Lyons (2004). The Palgrave Companion to North American Utopias. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 137.

11. Friesen, John W.; Friesen, Virginia Lyons (2004). The Palgrave Companion to North American Utopias. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 139.

12. Soland 2017, p. 63.

13. Pitzer, Donald (1997). America's Communal Utopias. Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press. p. 283.

14. Soland 2017, p. 64.

15. Ancestry.com's Missouri Registry of Deaths for the week of November 10, 1856, p. 122

16. Soland 2017, p. 65.

17. Some miscellaneous handwritten records of the Hancock County, Illinois court relative to "E. Cabbett" are available in ancestry.com's library edition, images 1117-1119 of 1825-1858 records

Further reading

• Johnson, Christopher H (1974). Utopian communism in France : Cabet and the Icarians, 1839-1851. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801408953. OCLC 1223569.

• Soland, Randall (2017). Utopian communities of Illinois : heaven on the prairie. Charleston, SC: History Press. ISBN 9781439661666. OCLC 1004538134.

• Sutton, Robert P. (1994). Les Icariens : the utopian dream in Europe and America. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252020674. OCLC 28215643.

External links

• Étienne Cabet from the Handbook of Texas Online

• Encyclopædia Britannica Etienne Cabet

• Archive of Etienne Cabet Papers at the International Institute of Social History

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 40037

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

Young Men's Indian Association

by Theosophy Wiki

Accessed: 8/27/20

Entrance to YMIA Building, Chennai

The Young Men's Indian Association (YMIA) is a youth organization that was founded by Annie Besant in 1914 in support of the Indian independence movement. It continues to be a prominent institution in Chennai, offering Indian youth opportunities to improve in body, mind, moral character, and citizenship.[1][2] It offers recreational facilities, lectures, library and reading room, and residences. The YMIA has a web page and a presence in Facebook.

Early history

By 1914, Annie Besant had already been working for some years on establishment of schools and organizations to support Indian education and nationalism. In a 1908 address at Central Hindu College, she said, "Our work is the training of thousands of India's sons into noble manhood into worthiness to become free citizens in a free land." [3] Her political activity reached greatest intensity in the years 1914-1917. She worked with several other nationalist leaders to demand home rule for India, and formation of the YMIA was one aspect of this movement.

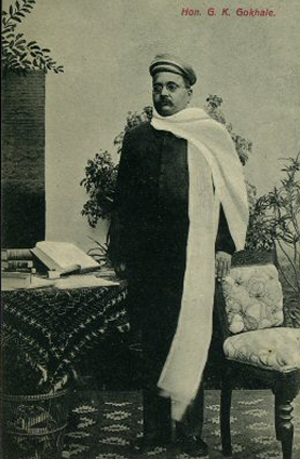

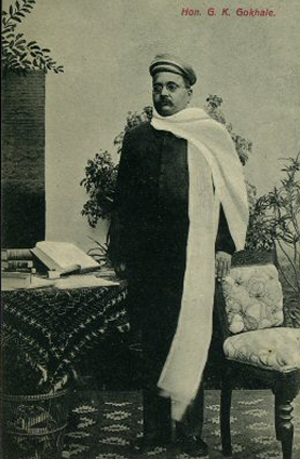

Mrs. Besant sponsored the construction of a building in Madras (now Chennai) for the YMIA, which was completed in 1915. A large public meeting hall in the building, designed to seat 1500 people, was given the name Gopal Krishna Gokhale Hall after the Indian leader. When she announced the formation of the Home Rule League in 1916, it was at Gokhale Hall. Many other nationalistic events took place there. The Indian Society of Oriental Art held an exhibition at the YMIA building in 1916, organized by Theosophist James Cousins.[4]

In his introduction to The Besant Spirit, George S. Arundale wrote of Dr. Besant's daily routine in Adyar during the time of her great activism in the Indian independence movement. Each evening at 5:30,

Objects of the Association

According to its web page, the Association has these objects:

• To provide a building or buildings as a Young Men’s Club, with gymnasium, lecture hall, library, reading-room, recreation-rooms and residential quarters, mainly for students.

• To draw together students of all classes and creeds under a common roof so that they may recognize their common interests as citizens, to enable them to have lectures discussions and classes, and so to train and develop their bodies that they may grow into strong and healthy men.

• To do all such things as are incidental or conducive to the attainment of the above objects or any of them.

• To promote the physical, social, intellectual and well being of young people of all classes, creeds and communities, to undertake and conduct social service schemes, to provide, equip, conduct and maintain residential, educational and social institution, activities facilities and amenities for its members and others, to co-operate with other organizations working with similar objects for the welfare of humanity and to stimulate the development of movements for the higher advancement of society.

• To establish, equip maintain and conduct branches, departments, center, offices refreshment rooms, hostels boarding houses, tourist homes, homes for destitute children, libraries, reading and lecture rooms, congresses, conferences, study classes, canteen, gymnasium swimming pool, social service centers, educational or social institutions activities, functions works facilities and amenities which may be necessary or convenient for the advancement of the purpose or objects of the Association or for the advantage or convenient of its members and others connected with the Association but no intoxicants of any whatsoever shall be provided, used, sold kept or allowed in or upon any premises belonging to or in the occupation of the Association.

• To establish, provide, organize, maintain, supervise, control and conduct institution for the study and appreciation of indigenous and foreign languages and literature, are and science, studies research centers, laboratories, conferences and lecture halls, scientific, industrial and art exhibition, demonstrations, congresses and exchanges, art galleries, music and halls, television and dramatic performances, debates, symposia, concerts, sports and competitions and generally any undertaking, scheme work or activity whatsoever for the mental, moral or physical improve or benefit of the members or other connected with the Association.

• To provide, organize, equip maintain and conduct premises holding classes and competitions to arrange for and give prizes in respect thereof, delivery of lectures, giving of demonstrations and holding of other functions in connection with scientific and artistic subjects and for examinations and awards of diplomas and certificates and to institute, administer and undertake grants scholarships, rewards and other beneficiaries.

• To investigate, collect and circulate any knowledge or information on any subject deemed desirable to the purposes of the Association and to print, publish and issue journals, periodicals, books, leaflets, advertisements, reports, lectures and other reading matter which may be deemed useful or expedient for any such purpose.

• To solicit accept, hold and d\administer any donations, gifts legacies grants, subscription contributions or funds from members the public institutions, public trusts, universities, municipalities governments and other persons or bodies and whether subjects to any trust or otherwise for the furtherance of the objects of the Association.

• To promote education, research training and development on habit and human settlement, environment and other related issues of human value.

Governance

YMIA is a society registered under the provisions of Act 21 of 1860. Mr. R. Nataraj serves as President of the Governing body, which includes three Vice Presidents, Honorary Secretary, Honorary Treasurer, Honorary Join Secretary, and 17 members. In addition to an Executive Committee, there are committees for International YMIA Affiliation; Library and Internet; Gym and Sports; Students and Youth Activities; and Legal matters.

Facilities

YMIA has two locations in Chennai: the registered office at New India Buildings at No.49 Moore Street, and the administrative office at 54-57/2 Royapettah High Road in Mylapore. Gokhale Hall was partially demolished, but is now being renovated. Two hostels are now serving about 150 youth. Over the years additional hostels were operated in George town, Triplicane, Mylapore, and Nungambakkam, but these had to be closed despite their popularity.[6]

YMIA celebrating Annie Besant's birthday, October 1, 2014.

Activities

The organization has established a Facebook page and is developing a member page with individual photos and email addresses. YMIA is seeking to launch affiliated branches in all major cities of India, with each having a lecture hall, gymnasium, library, reading room, recreation, and residences. Internships are offered to students who would like to develop a career in services and development of youth programs.[7]

These are some recent activities and services of the YMIA:

• Sports, boxing, karate, and body building

• Fine arts competitions

• Carrom (a tabletop game) and chess

• Oratorical contests in 4 languages ( English, Tamil, Hindi, Telugu)

• Blood drive

• Republic Day celebrations

• Celebration of Swami Vivekananda's 150th birthday

• Memorial lectures and elocution contests honoring Dr. Annie Besant

• CDs of Annie Besant’s speeches

Notes

1. YMIA web page

2. Madras High Court document. 1962. Citation: AIR 1964 Mad 63, 1963 14 STC 1030 Mad Available at IndianKanoon.org.

3. Annie Besant, The Besant Spirit Volume 7: The India that Shall Be: Articles from New India.

4. Kathleen Taylor, Sir John Woodroffe Tantra and Bengal: 'An Indian Soul in a European Body?' (Surrey: Routledge, 2012), 70.

5. George S. Arundale, Introduction to The Besant Spirit: Volume III Indian Problems (Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1939), 13-14. The Besant Spirit is a compilation of writings by Annie Besant.

6. Young Men's Indian Association web page.

7. Young Men's Indian Association web page.

by Theosophy Wiki

Accessed: 8/27/20

Entrance to YMIA Building, Chennai

The Young Men's Indian Association (YMIA) is a youth organization that was founded by Annie Besant in 1914 in support of the Indian independence movement. It continues to be a prominent institution in Chennai, offering Indian youth opportunities to improve in body, mind, moral character, and citizenship.[1][2] It offers recreational facilities, lectures, library and reading room, and residences. The YMIA has a web page and a presence in Facebook.

Early history

By 1914, Annie Besant had already been working for some years on establishment of schools and organizations to support Indian education and nationalism. In a 1908 address at Central Hindu College, she said, "Our work is the training of thousands of India's sons into noble manhood into worthiness to become free citizens in a free land." [3] Her political activity reached greatest intensity in the years 1914-1917. She worked with several other nationalist leaders to demand home rule for India, and formation of the YMIA was one aspect of this movement.

Mrs. Besant sponsored the construction of a building in Madras (now Chennai) for the YMIA, which was completed in 1915. A large public meeting hall in the building, designed to seat 1500 people, was given the name Gopal Krishna Gokhale Hall after the Indian leader. When she announced the formation of the Home Rule League in 1916, it was at Gokhale Hall. Many other nationalistic events took place there. The Indian Society of Oriental Art held an exhibition at the YMIA building in 1916, organized by Theosophist James Cousins.[4]

In his introduction to The Besant Spirit, George S. Arundale wrote of Dr. Besant's daily routine in Adyar during the time of her great activism in the Indian independence movement. Each evening at 5:30,