Gary Larson

1981

"And so, without further ado, here's the author of Mind Over Matter..."

In 1781–82 Antoine-Louis-Henri Polier, a Swiss Protestant who served in the English East India Company’s army until 1775, had had copies of the Vedas made for him at the court of Pratap Singh at Jaipur. Polier’s intermediary was a Portuguese physician, Don Pedro da Silva Leitão… Jai Singh had assembled a substantial collection of manuscripts from religious sites across India, and in the time of his successor Pratap Singh the library had contained the samhitas of all four Vedas in manuscripts dating from the last quarter of the seventeenth century…

Polier records that he had sought copies of the Veda without success in Bengal, Awadh, and on the Coromandel coast, as well as in Agra, Delhi, and Lucknow and had found that even at Banaras “nothing could be obtained but various Shasters, [which] are only Commentaries of the Baids”…

It is perhaps significant that it was in a royal library, rather than in a Brahmin pathasala, that Polier found manuscripts of the Vedas. But the same is not true of the manuscripts acquired in Banaras only fifteen years later by Henry Thomas Colebrooke, during the period (1795–97) when he was appointed as judge and magistrate at nearby Mirzapur…I cannot conceive how it came to be ever asserted that the Brahmins were ever averse to instruct strangers; several gentlemen who have studied the language find, as I do, the greatest readiness in them to give us access to all their sciences. They do not even conceal from us the most sacred texts of their Vedas.

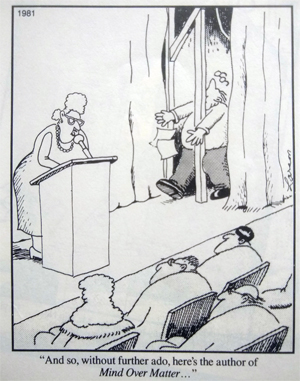

The several gentlemen would likely have included General Claude Martin, Sir William Jones, and Sir Robert Chambers. These were all East India Company employees who obtained Vedic manuscripts (Jones from Polier) in the last decades of the eighteenth century.

Why was it so much easier for Polier, Colebrooke, and others to obtain what it had been so difficult for the Jesuits and impossible for the Pietists?...

-- The Absent Vedas, by Will Sweetman

The Mississippi Company (French: Compagnie du Mississippi; founded 1684, named the Company of the West from 1717, and the Company of the Indies from 1719) was a corporation holding a business monopoly in French colonies in North America and the West Indies. When land development and speculation in the region became frenzied and detached from economic reality, the Mississippi bubble became one of the earliest examples of an economic bubble.

In May 1716, the Scottish economist John Law, who had been appointed Controller General of Finances of France under the Duke of Orleans, created the Banque Générale Privée ("General Private Bank"). It was the first financial institution to develop the use of paper money. It was a private bank, but three quarters of the capital consisted of government bills and government-accepted notes. In August 1717, Law bought the Mississippi Company to help the French colony in Louisiana. In the same year Law conceived a joint-stock trading company called the Compagnie d'Occident (The Mississippi Company, or, literally, "Company of [the] West"). Law was named the Chief Director of this new company, which was granted a trade monopoly of the West Indies and North America by the French government.

The bank became the Banque Royale (Royal Bank) in 1718, meaning the notes were guaranteed by the king, Louis XV of France. The company absorbed the Compagnie des Indes Orientales ("Company of the East Indies"), the Compagnie de Chine ("Company of China"), and other rival trading companies and became the Compagnie Perpetuelle des Indes on 23 May 1719 with a monopoly of French commerce on all the seas. Simultaneously, the bank began issuing more notes than it could represent in coinage; this led to a currency devaluation, which was eventually followed by a bank run when the value of the new paper currency was halved.

Louis XIV's long reign and wars had nearly bankrupted the French monarchy. Rather than reduce spending, the Regency of Louis XV of France endorsed the monetary theories of Scottish financier John Law. In 1716, Law was given a charter for the Banque Royale under which the national debt was assigned to the bank in return for extraordinary privileges. The key to the Banque Royale agreement was that the national debt would be paid from revenues derived from opening the Mississippi Valley. The Bank was tied to other ventures of Law—the Company of the West and the Companies of the Indies. All were known as the Mississippi Company. The Mississippi Company had a monopoly on trade and mineral wealth. The Company boomed on paper. Law was given the title Duc d'Arkansas. Bernard de la Harpe and his party left New Orleans in 1719 to explore the Red River. In 1721, he explored the Arkansas River. At the Yazoo settlements in Mississippi he was joined by Jean Benjamin who became the scientist for the expedition.

In 1718, there were only 700 Europeans in Louisiana. The Mississippi Company arranged ships to move 800 more, who landed in Louisiana in 1718, doubling the European population. Law encouraged some German-speaking peoples, including Alsatians and Swiss, to emigrate. They give their name to the regions of the Côte des Allemands and the Lac des Allemands in Louisiana.

Prisoners were set free in Paris from September 1719 onwards, under the condition that they marry prostitutes and go with them to Louisiana. The newly married couples were chained together and taken to the port of embarkation. In May 1720, after complaints from the Mississippi Company and the concessioners about this class of French immigrants, the French government prohibited such deportations. However, there was a third shipment of prisoners in 1721.

Law exaggerated the wealth of Louisiana with an effective marketing scheme, which led to wild speculation on the shares of the company in 1719. The scheme promised success for the Mississippi Company by combining investor fervor and the wealth of its Louisiana prospects into a sustainable, joint-stock, trading company. The popularity of company shares were such that they sparked a need for more paper bank notes, and when shares generated profits the investors were paid out in paper bank notes. In 1720, the bank and company were merged and Law was appointed by Philippe II, Duke of Orleans, then Regent for Louis XV, to be Comptroller General of Finances to attract capital. Law's pioneering note-issuing bank thrived until the French government was forced to admit that the number of paper notes being issued by the Banque Royale exceeded the value of the amount of metal coinage it held.

The "bubble" burst at the end of 1720, when opponents of the financier attempted to convert their notes into specie (gold and silver) en masse, forcing the bank to stop payment on its paper notes. By the end of 1720 Philippe d'Orléans had dismissed Law from his positions. Law then fled France for Brussels, eventually moving on to Venice, where he lived off his gambling. He was buried in the church San Moisè in Venice.

-- Mississippi Company, by Wikipedia

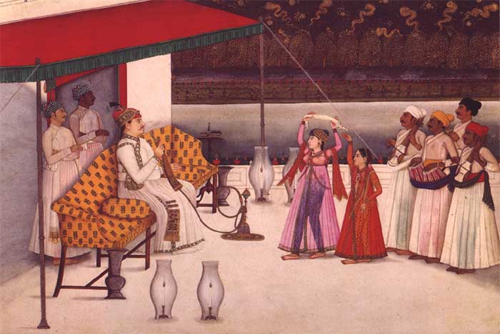

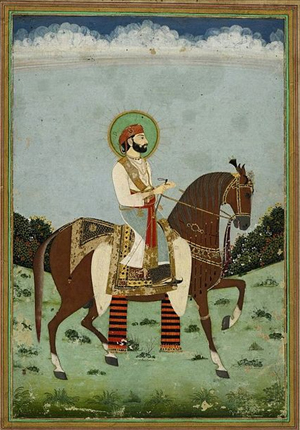

Asaf-ud-Daula (Hindi: आसफ़ उद दौला, Urdu: آصف الدولہ) (b. 23 September 1748 – d. 21 September 1797) was the Nawab wazir of Oudh (a vassal of the British) ratified by Shah Alam II, from 26 January 1775 to 21 September 1797, and the son of Shuja-ud-Dowlah. His mother and grandmother were the Begums of Oudh.

Asaf-ud-Daula became nawab at the age of 26, on the death of his father, Shuja-ud-daula, on 28 January 1775. He assumed the throne with the aid of the British East India Company, outmanoeuvring his younger brother Saadat Ali who led a failed mutiny in the army. British Colonel John Parker defeated the mutineers decisively, securing Asaf-ud-Daula's succession. His first chief minister was Mukhtar-ud-Daula who was assassinated in the revolt.

The other challenge to Asaf's rule was his mother Umat-ul-Zohra (better known as Bahu Begum), who had amassed considerable control over the treasury and her own jagirs and private armed forces. She at one pointed invited the Company to intervene in her favour in the appointment of ministers against Asaf. When Shuja-ud-Daula died he left two million pounds sterling buried in the vaults of the zenana. The widow and mother of the deceased prince claimed the whole of this treasure under the terms of a will which was never produced. When Warren Hastings pressed the nawab for the payment of debt due to the Company, he obtained from his mother a loan of 26 lakh (2.6 million) rupees, for which he gave her a jagir (land) of four times the value; of subsequently obtained 30 lakh (3 million) more in return for a full acquittal, and the recognition of her jagirs without interference for life by the Company. These jagirs were afterwards confiscated on the ground of the begum's [Umat-ul-Zohra] complicity in the rising of Chait Singh, which was attested by documentary evidence. Ultimately this removed Umat-ul-Zohra as an obstacle to Asaf's reign.

In the aftermath of Saadat's revolt, Asaf sought to restructure the government particularly by appointing nobles favourable to his cause and British officers to his military. Asaf appointed Hasan Riza Khan as his chief minister. Although he had little experience in administration, his assistant Haydar Beg Khan turned out to be a valuable support. Tikayt Ray was appointed finance minister.

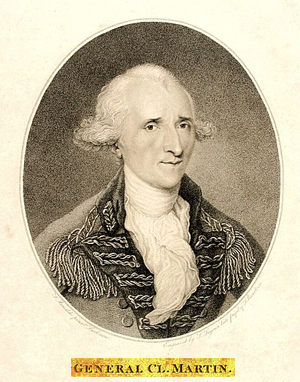

He was known for his generosity, particularly the offering of food and public employment in times of famine. Notably, the Bara Imambara, a mosque in Lucknow, was constructed during his reign by destitute workers seeking employment.

The Asfi mosque, located near the Imambara

A popular saying of the time of his benevolence: jisko na de maulā, usko de Asaf-ud-daulā "to whom even God does not give, Asaf-ud-Daula gives..."

Nawab Asaf-ud-Dowlah is considered the architect general of Lucknow. With the ambition to outshine the splendour of Mughal architecture, he built a number of monuments and developed the city of Lucknow into an architectural marvel....

The Nawab's sensitivity towards preserving the reputation of the upper class is demonstrated in the story of the construction of Imambara. During daytime, common citizens employed on the project would construct the building. On the night of every fourth day, the noble and upper-class people were employed in secret to demolish the structure built, an effort for which they received payment. Thus their dignity was preserved.

-- Asaf-ud-Daula, by Wikipedia

His favourite mistress was a girl called Boulone (c.1766–1844), who was some thirty years younger than Martin. He had bought her as a young girl aged nine. Martin always claimed that they lived happily together, but Boulone must inevitably have harboured feelings of jealousy when Martin introduced younger mistresses into the household.

"Most excellent in government, Sword of the Realm, Supreme amongst Knights, General Claude Martin the Brave, Courageous in War. 1796- 1797."[6]

The will of Claude Martin

Last Will and Testament made and written by me, Claude Martin, Major General in the Honourable Company services, Bengal Establishment, having destroyed any former ones, or intended to destroy them in case I have time to do it. This present one I declare being the only good one in which faith is to be put and which I require my executors, Administrators or Assigns will put in execution and adhere to and any other will or testament existing I may have forgotten to destroy, and differing from the substances, or intentions of the several articles of this one, I declare them null and of no force value, but this present one being made and written by me in my sound senses and good health. This first day of January in the year one thousand eight hundred (or the year 1800) witness my hand and seal as under this and at the end of the page.

Claude Martin

"In the name of the Supreme Almighty God, Creator of the Universe and which exists on the Globe and respectful thanks to be admitted at the feet of this sublime unknown, unseen and Incomprehensible Omnipotent. For the happiness I have enjoyed on this Globe during the time his usual Benevolence allowed me, as also for the Inducement and time allowed me in making and writing this my last will and Testament in favour of those concerned in it in hope it will be fulfilled in its extent, wishing them every happiness possible in this and the other world. My most exalted praise and most respectful thanks be received by the Almighty Creator of all who exist for his most kind clemency to me during my life, being merciful to all, I have great hope he will pardon me the sins I have committed"

"All the women, Males and women servants, Eunuchs and others that are belonging to me, and for which I have paid for, to have them as my own property, at my Death or the soul essence of life quitting my Material body, I give them their freedom and they are free except those as hereafter mentioned which I had already disposed in favour of those undernamed having acquired, bought, brought up and educated them to be their servants and attendants during the lives of those with whom I have placed them or given said Males or Women or Eunuchs as servants attending on these Mistresses during their life time and no longer..............Having every reason to be satisfied of their services, for these reasons my sincere wishes are to give them their proper reward in this world. For all these above my only anxiety is the Idea that perhaps nobody would be so interested for their welfare as I am, after having lost me, and for the support and protection they will or may be therein need of."

"I give and bequeath the sum of one hundred and fifty thousand rupees to be placed at Interest in the most secure manner possible in the East India Company or Government papers bearing interest and that interest to be employed for the poor, first having divided this Interest in three portions or parts: one- for the relief of the poor of Lucknow of christian religion, (second)-for the poor of Calcutta- and (third) for the relief of the Poor of Chandernaggur......................

"I give and bequeath the sum of five thousand sicca Rupees to be paid Annually to the Magistrate or Supreme Court of Calcutta -- to pay the debt of some poor honest debtor detained in Jail for small sum -- and as being a soldier I would wish to prefer liberating any poor officer or other Military men detained for small debt................"

"I give and bequeath the sum of two hundred thousand sicca rupees to the Town of Calcutta to be put at Interest under the protection of Government of the Supreme Court that they may desire an Institution the most necessary for the public good of the Town of Calcutta or establishing a School to educate a certain number of Children of any sex to a certain age, to have them put in apprenticeship to some profession.............and to have them married when at age...........and a medal to be given to the most deserving or virtuous boy or girl............"

"Since the powerful Almighty creator of all the Universe of all that exist gave me the power and wisdom of thinking, I never discontinued contemplating and admiring his wisdom in the creation and Ruling the Universe, as also the several Globes, Planets, Stars and firmament, things incomprehensible to men's feeble understanding. I was born and educated to believe in the existence of God Ruler of all the World and all that exist beneficent to all of any Religion or sects they may be, being Gratefully bound to thank him for his mercifulness on me, I adored him and worshipped him as my Creator Benefactor and all omnipotent, but doubtful of the mode of worshipping Him. I did it as a child of the earth, though educated in the Roman Catholic Religion, but when my bodily feeling made one weak I resumed the prejudices I had imbibed by my education and salvation of my said Immortal Soul; I worshiped him as I had been taught in my infancy.........but, as still many doubts crowded in my mind, I never could cease enquiring of the true path of Religion and worshiping the Omnipotent Creator God and I have endeavoured to learn the religion of other nations and sects that I might be a proper judge for myself and, though I found mostly every other nations and sects as ridiculous in their ceremony as I thought the Religion I was educated in, still I found a similarity in the same principle and the substance of every Religion of Nations and sects (with which) I have been acquainted, of all possession, sound moral, and recommendation, to do all the good possible to other creatures, to worship as only God, creator of all, and to be charitable to all other creatures and to do Penances for sin............"

"When I am dead, which I suppose will happen at Lucknow, unless in the field of honour against an enemy; if at Lucknow or anywhere else, I request that my body may be salted, put in spirit or embalmed, and afterwards deposited in a leaden Coffin made of some sheet lead in my Godown and this coffin be put in another wooden one of sisson wood of thick plank of two inches thick, and this deposited in the cave of my monument or house at Luckperra, called Constantia, in that cave and in the small round room North Easterly to erect a tomb of about two feet, elevated from the floor, and to have the Coffin deposited in it and the tomb to be covered with a marble stone, and an Inscription put on it of my name Major General Claude Martin, Born at Lyons, the 5th January, 1735, arrived in India a common soldier and died at the........month in the year......and he is buried in this Tomb. Pray for his soul."

Written by me in my perfect health and sound senses, the first January, in the year of our Lord, Eighteen hundred.

signed and sealed by me

(Cl MARTIN, (L.S.)

Witness of my signature and seal signed and sealed before us, where no stamp paper is to be had.

(Sd.) D. LUMSDEN, Captain, in the Hon'ble Company

(Sd.) J. REID, Surgeon, in the Hon'ble Company

Done before me,

(Sd.) WILLIAM SCOTT,

Resident, Lucknow

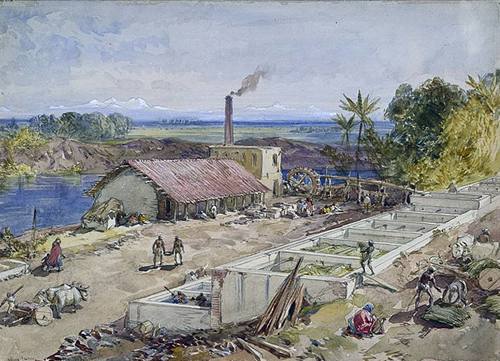

Indigo planting in Bengal dated back to 1777 when Louis Bonnard, a Frenchman introduced it to the Indians. He was the first indigo planter of Bengal. He started cultivation at Taldanga and Goalpara near Chandannagar (Hooghly).With the Nawabs of Bengal under British power, indigo planting became more and more commercially profitable because of the demand for blue dye in Europe. It was introduced in large parts of Burdwan, Bankura, Birbhum, North 24 Parganas, and Jessore (present Bangladesh). The indigo planters persuaded the peasants to plant indigo instead of food crops. They provided loans, called dadon, at a very high interest. Once a farmer took such loans he remained in debt for his whole life before passing it to his successors. The price paid by the planters was meagre, only 2.5% of the market price. The farmers could make no profit growing indigo. The farmers were totally unprotected from the indigo planters, who resorted to mortgages or destruction of their property if they were unwilling to obey them. Government rules favoured the planters. By an act in 1833, the planters were granted a free hand in oppression. Even the zamindars sided with the planters. Under this severe oppression, the farmers resorted to revolt.

The Bengali middle class supported the peasants wholeheartedly. Bengali intellectual Harish Chandra Mukherjee described the plight of the poor farmer in his newspaper The Hindu Patriot. However the articles were overshadowed by Dinabandhu Mitra, who depicted the situation in his play Nil Darpan. His play created a huge controversy which was later banned by the East India Company to control the agitation among the Indians.

The revolt was ruthlessly suppressed. Large forces of police and military, backed by the British Government and the zamindars, mercilessly slaughtered a number of peasants. British police mercilessly hanged great leader of indigo rebels Biswanath Sardar alias Bishe Dakat in Assannagar, Nadia after a show trial. Some historians opined that he was the first martyr of indigo revolt in undivided Bengal...

R.C. Majumdar in "History of Bengal" goes so far as to call it a forerunner of the non-violent passive resistance later successfully adopted by Gandhi. The revolt had a strong effect on the government, which immediately appointed the "Indigo Commission" in 1860. In the commission report, E. W. L. Tower noted that "not a chest of Indigo reached England without being stained with human blood".

-- Indigo revolt, by Wikipedia

"I give and bequeath the sum of one hundred and fifty thousand rupees for to be placed at Interest in the most secure manner possible in the East India Company or Government papers bearing interest and that interest to be employed for the poor first having divided this Interest in three portions or parts one – for the relief of the poor of Lucknow of any religion – for the poor of Calcutta – for the relief of the Poor of Chandernaggur".

La Martinière College is a consortium of bi-national private schools, majority of them located in India. They are officially non-denominational private schools with units of two-two branches in Indian cities of (Kolkata and Lucknow) respectively and in France, the consortium is represented by a number of three branches in Lyons.

La Martinière Schools were founded posthumously by Major General Claude Martin, in the early 19th century... His will outlined every detail of the schools, from their location to the manner of celebrating the annual Founder's Day. The seven branches function independently, but maintain close contacts and share most traditions.

La Martinière College, Lucknow was awarded a Battle Honour - 'Defense of Lucknow' for the part the staff and pupils played in the Defence of the Residency at Lucknow during the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 -- the only school in the world so distinguished.

La Martiniere Calcutta and La Martinière Lucknow consist of separate girls' and boys' schools, while the three in La Martinière Lyon are co-educational. The Colleges are day schools, but Indian units have boarding facilities as well. Extra-curricular activities, including sports and community service organizations, are emphasized, and music and dance are included in the general curriculum...

The Socials at La Martinière are elegant events in the English tradition. Students from both the girls and boys sections are invited to the socials. Ceremonial uniform is worn by boys, while formal dresses are worn by girls. "The Social" is a tradition of La Martiniere and a memory of its English past.

The Socials are held in the College Hall and the girls are invited to the boys school. Socials are also held after the yearly 'Inter-Martiniere Meet' is held between the two schools at Lucknow and Kolkata.

La Martinière has always been regarded as one of the finest schools in India. Given its foundation in English tradition, it has been compared to the Public Schools of England, and has been referred to as "The Eton of the East" by William Dalrymple, in his book "The Age of Kali."

-- La Martiniere College, by Wikipedia

"I have read a lot, pen in hand, often under difficult conditions, and I know the value of the first rudiments inculcated by the parson of St. Saturnin. That is why I divide my fortune in two. I want to thank all those who have been around me by making their life easier after my death. I also want to give the children of both Lyon and India, the instruction which I received with so much difficulty. I want to make it easy for young people to get access to knowledge, specially the sciences."[9]

Adventurer: a person who enjoys or seeks adventure; a person willing to take risks or use dishonest methods for personal gain; "a political adventurer"; a financial speculator.

-- Adventurer, by Google

"I have always refused to give up the French nationality, but of which France do I belong? That of Louis XV, where I have only known misery before embarking on the L'Orient? That of philosophers, of terror bathing in blood, or that of Bonaparte whose eastern dream has just been dissipated, after leaving Tipu Sahib alone against the English? I have collaborated for his defeat and then after he lost I have been rewarded by some gold sprinkling on my uniform-a vain plaything for my vanity. By my persevarance and hard work I have accumulated a fortune from this country which is my second motherland. I have not cheated the people who have passively succumbed to the yoke of corrupt men."

Major-General Claude Martin.

Arrived in India as a common soldier

and died at Lucknow on the 13th of September,

1800, as a Major-General.

He is buried in this tomb.

Pray for his soul."[11]

In 1781–82 Antoine-Louis-Henri Polier, a Swiss Protestant who served in the English East India Company’s army until 1775, had had copies of the Vedas made for him at the court of Pratap Singh at Jaipur. Polier’s intermediary was a Portuguese physician, Don Pedro da Silva Leitão… Jai Singh had assembled a substantial collection of manuscripts from religious sites across India, and in the time of his successor Pratap Singh the library had contained the samhitas of all four Vedas in manuscripts dating from the last quarter of the seventeenth century…

Polier records that he had sought copies of the Veda without success in Bengal, Awadh, and on the Coromandel coast, as well as in Agra, Delhi, and Lucknow and had found that even at Banaras “nothing could be obtained but various Shasters, [which] are only Commentaries of the Baids”…

It is perhaps significant that it was in a royal library, rather than in a Brahmin pathasala, that Polier found manuscripts of the Vedas. But the same is not true of the manuscripts acquired in Banaras only fifteen years later by Henry Thomas Colebrooke, during the period (1795–97) when he was appointed as judge and magistrate at nearby Mirzapur…I cannot conceive how it came to be ever asserted that the Brahmins were ever averse to instruct strangers; several gentlemen who have studied the language find, as I do, the greatest readiness in them to give us access to all their sciences. They do not even conceal from us the most sacred texts of their Vedas.

The several gentlemen would likely have included General Claude Martin, Sir William Jones, and Sir Robert Chambers. These were all East India Company employees who obtained Vedic manuscripts (Jones from Polier) in the last decades of the eighteenth century.

Why was it so much easier for Polier, Colebrooke, and others to obtain what it had been so difficult for the Jesuits and impossible for the Pietists?...

-- The Absent Vedas, by Will Sweetman

In the 1770s, Johnson, who had tended to be an opponent of the government early in life, published a series of pamphlets in favour of various government policies...

The last of these pamphlets, Taxation No Tyranny (1775), was a defence of the Coercive Acts and a response to the Declaration of Rights of the First Continental Congress of America, which protested against taxation without representation. Johnson argued that in emigrating to America, colonists had "voluntarily resigned the power of voting", but they still had "virtual representation" in Parliament. In a parody of the Declaration of Rights, Johnson suggested that the Americans had no more right to govern themselves than the Cornish people, and asked "How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of negroes?" If the Americans wanted to participate in Parliament, said Johnson, they could move to England and purchase an estate. Johnson denounced English supporters of American separatists as "traitors to this country", and hoped that the matter would be settled without bloodshed, but he felt confident that it would end with "English superiority and American obedience".[145]

-- Samuel Johnson, by Wikipedia

Maharaja Nandakumar, also called Nuncomar (1705? - died 5 August 1775), was a collector of taxes, a dewan, for various areas in what is now West Bengal. Nanda Kumar was born at Bhadrapur, which is now in Birbhum. He was India's first victim of hanging under British rule. He was appointed by the East India Company to be the collector of taxes for Burdwan, Nadia and Hoogly in 1764, following the removal of Warren Hastings from the post.

In 1773, when Warren Hastings was re-instated as governor-general of Bengal, Nandakumar brought accusations of Warren Hastings accepting bribes that were entertained by Sir Philip Francis and the other members of the Supreme Council of Bengal. However, Warren Hastings could overrule the Council's charges. Thereafter, in 1775 Warren Hastings brought charges of document forgery against the Maharaja. The Maharaja was tried under Elijah Impey, India's first Chief Justice, and friend of Warren Hastings, was found guilty, and hanged in Kolkata on 5 August 1775.

Later Hastings, along with Sir Elijah Impey, the chief justice, was impeached by the British Parliament. They were accused by Burke (and later by Macaulay) of committing judicial murder...

He held posts under Nawab of Murshidabad. After the Battle of Plassey, he was recommended to Robert Clive for appointment as their agent to collect revenues of Burdwan, Nadia and Hooghly. The title "Maharaja" was conferred on Nandakumar by Shah Alam II in 1764. He was appointed Collector of Burdwan, Nadia, and Hugli by the East India Company in 1764, in place of Warren Hastings. He learnt Vaishnavism from Radhamohana Thakura.

Maharaja Nandakumar accused Hastings of bribing him with more than one-third of a million rupees and claimed that he had proof against Hastings in the form of a letter...

Warren Hastings was then with the East India Company and happened to be a school friend of Sir Elijah Impey. Some historians are of the opinion that Maharaja Nandakumar was falsely charged with forgery and Sir Elijah Impey, the first Chief Justice of Supreme Court in Calcutta, gave judgement to hang Nandakumar. Nandakumar's hanging was called a judicial murder by certain historians. Macaulay also accused both men of conspiring to commit a judicial murder. Maharaja Nandakumar was hanged at Calcutta, near present-day Vidyasagar Setu, during Warren Hastings' rule on 5 August 1775. In those days the punishment for forgery was hanging by the Forgery Act, 1728 passed by the British Parliament in England (United Kingdom), but the law was construed for the people committing forgery in England due to the then prevailing conditions in England and there was no provision in the law that it is applicable in India too.

-- Maharaja Nandakumar, by Wikipedia

The Judicial Notebooks of John Hyde and Sir Robert Chambers, 1774-1798, are a unique source of primary historical information for the early years of the Supreme Court and life in India. The court notebooks do not tell a single story but are a dense repository of legal and social action over time.

-- Hyde Reports, by Justice John Hyde and Sir Robert Chambers [and William Jones]

In 1781–82 Antoine-Louis-Henri Polier, a Swiss Protestant who served in the English East India Company’s army until 1775, had had copies of the Vedas made for him at the court of Pratap Singh at Jaipur. Polier’s intermediary was a Portuguese physician, Don Pedro da Silva Leitão… Jai Singh had assembled a substantial collection of manuscripts from religious sites across India, and in the time of his successor Pratap Singh the library had contained the samhitas of all four Vedas in manuscripts dating from the last quarter of the seventeenth century…

Polier records that he had sought copies of the Veda without success in Bengal, Awadh, and on the Coromandel coast, as well as in Agra, Delhi, and Lucknow and had found that even at Banaras “nothing could be obtained but various Shasters, [which] are only Commentaries of the Baids”…

It is perhaps significant that it was in a royal library, rather than in a Brahmin pathasala, that Polier found manuscripts of the Vedas. But the same is not true of the manuscripts acquired in Banaras only fifteen years later by Henry Thomas Colebrooke, during the period (1795–97) when he was appointed as judge and magistrate at nearby Mirzapur…I cannot conceive how it came to be ever asserted that the Brahmins were ever averse to instruct strangers; several gentlemen who have studied the language find, as I do, the greatest readiness in them to give us access to all their sciences. They do not even conceal from us the most sacred texts of their Vedas.

The several gentlemen would likely have included General Claude Martin, Sir William Jones, and Sir Robert Chambers. These were all East India Company employees who obtained Vedic manuscripts (Jones from Polier) in the last decades of the eighteenth century.

Why was it so much easier for Polier, Colebrooke, and others to obtain what it had been so difficult for the Jesuits and impossible for the Pietists?...

-- The Absent Vedas, by Will Sweetman

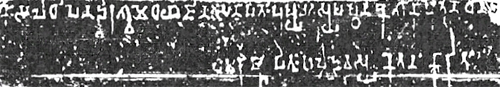

In the early progress of researches into Indian literature, it was doubted whether the Vedas were extant; or, if portions of them were still preserved, whether any person, however learned in other respects, might be capable of understanding their obsolete dialect. It was believed too, that, if a Brahmana really possessed the Indian scriptures, his religious prejudices would nevertheless prevent his imparting the holy knowledge to any but a regenerate Hindu. These notions, supported by popular tales, were cherished long after the Vedas had been communicated to Dara Shucoh [Shikoh], and parts of them translated into the Persian language by him, or for his use. [Extracts have also been translated into the Hindi language; but it does not appear upon what occasion this version into the vulgar dialect was made.] The doubts were not finally abandoned, until Colonel Polier obtained from Jeyepur a transcript of what purported to be a complete copy of the Vedas, and which he deposited in the British Museum. About the same time Sir Robert Chambers collected at Benares numerous fragments of the Indian scripture: General Martine [General Claude Martin]: at a later period, obtained copies of some parts of it; and Sir William Jones was successful in procuring valuable portions of the Vedas, and in translating several curious passages from one of them. [See Preface to Menu, page vi. and the Works of Sir William Jones, vol. vi.] I have been still more fortunate in collecting at Benares the text and commentary of a large portion of these celebrated books; and, without waiting to examine them more completely than has been yet practicable, I shall here attempt to give a brief explanation of what they chiefly contain.

-- Essays on the Religion and Philosophy of the Hindus, by Henry Thomas Colebrooke, Esq.

Adventurer: a person who enjoys or seeks adventure; a person willing to take risks or use dishonest methods for personal gain; "a political adventurer"; a financial speculator.

-- Adventurer, by Google

Our Story

Mission

To improve the quality of research and education in universities by increasing open inquiry, viewpoint diversity, and constructive disagreement.

Vision

We aspire to create college classrooms and campuses that welcome diverse people with diverse viewpoints and that equip learners with the habits of heart and mind to engage that diversity in open inquiry and constructive disagreement.

We see an academy eager to welcome professors, students, and speakers who approach problems and questions from different points of view, explicitly valuing the role such diversity plays in advancing the pursuit of knowledge, discovery, growth, innovation, and the exposure of falsehoods.

Who we are

Heterodox Academy (HxA) is a nonpartisan collaborative of thousands of professors, administrators, and students committed to enhancing the quality of research and education by promoting open inquiry, viewpoint diversity, and constructive disagreement in institutions of higher learning. All of our members embrace a set of norms and values, which we call “The HxA Way.”

All our members have embraced the following statement:“I support open inquiry, viewpoint diversity, and constructive disagreement in research and education.”

HxA’s members — professors, administrators, staff, and graduate students — come from a range of public and private institutions, from large research institutions to community colleges. They represented nearly every discipline, and are distributed throughout all 50 states and beyond.

What we do“No organization in the history of American academic life has done, or is doing, more to promote the basic freedoms of viewpoint diversity we urgently need in our colleges and universities today than Heterodox Academy.”

-Robert George, Legal Scholar, Political Philosopher, & HxA Advisory Council member

In order to address society’s most intractable problems, learners must weave together the best ideas from a range of perspectives. Yet, colleges — the intended training ground for the sort of creative and integrative thinking such problem-solving requires — have become increasingly characterized by orthodoxy in what types of questions can be asked and what sort of comments can be shared in the classroom and around campus. Professors and students alike describe the toll self-censoring and threat of social censure have taken on learning, discovery, and growth. For the sake of higher ed and all the enterprises of life that await students after graduation, now is the time to dig in and fix what’s broken.

Heterodox Academy has the expertise, tools, and profile necessary to make change happen. We increase public awareness to elevate the importance of these issues on campus; develop tools that professors, administrators, and others can deploy to assess and then improve their campus and disciplinary cultures; publicly recognizing model institutions; and cultivate communities of practice among teachers, researchers, and administrators.

History

Heterodox Academy was founded in 2015 by Jonathan Haidt, Chris Martin, and Nicholas Rosenkranz, in reaction to their observations about the negative impact a lack of ideological diversity has had on the quality of research within their disciplines. What began as a website and a blog in September of 2015 — a venue for social researchers to talk about their work and the challenges facing their disciplines and institutions — soon grew into an international network of peers dedicated to advancing the values of constructive disagreement and viewpoint diversity as cornerstones of academic and intellectual life...

Heterodox Academy is comprised of nearly 4,000 members from a range of demographic backgrounds and academic disciplines, holding various institutional roles all over the United States and beyond. As would be expected from such a heterogenous network, our members hold a range of views on virtually any topic up for discussion. As an organization, we prize pluralism and we value constructive disagreement.

However, we do not promote viewpoint diversity for its own sake. Our primary goal is to improve research and teaching at colleges and universities. We recognize that institutions of higher learning are not ‘public squares’ in the traditional sense, but rather sites for the production and dissemination of knowledge. To facilitate these objectives, we embrace a particular set of norms and values, which we have taken to calling the ‘HxA Way.’ We encourage our members to embody these in all of their professional interactions.

1. Make your case with evidence.

Link to that evidence whenever possible (for online publications, on social media), or describe it when you can’t (such as in talks or conversations). Any specific statistics, quotes or novel facts should have ready citations from credible sources.

2. Be intellectually charitable.

Viewpoint diversity is not incompatible with moral or intellectual rigor – in fact it actually enhances moral and intellectual agility. However, one should always try to engage with the strongest form of a position one disagrees with (that is, ‘steel-man’ opponents rather than ‘straw-manning’ them). One should be able to describe their interlocutor’s position in a manner they would, themselves, agree with (see: ‘Ideological Turing Test’). Try to acknowledge, when possible, the ways in which the actor or idea you are criticizing may be right — be it in part or in full. Look for reasons why the beliefs others hold may be compelling, under the assumption that others are roughly as reasonable, informed and intelligent as oneself.

3. Be intellectually humble.

Take seriously the prospect that you may be wrong. Be genuinely open to changing your mind about an issue if this is what is expected of interlocutors (although the purpose of exchanges across difference need not always be to ‘convert’ someone, as explained here). Acknowledge the limitations to one’s own arguments and data as relevant.

4. Be constructive.

The objective of most intellectual exchanges should not be to “win,” but rather to have all parties come away from an encounter with a deeper understanding of our social, aesthetic and natural worlds. Try to imagine ways of integrating strong parts of an interlocutor’s positions into one’s own. Don’t just criticize, consider viable positive alternatives. Try to work out new possibilities, or practical steps that could be taken to address the problems under consideration. The corollary to this guidance is to avoid sarcasm, contempt, hostility, and snark. Generally target ideas rather than people. Do not attribute negative motives to people you disagree with as an attempt at dismissing or discrediting their views. Avoid hyperbole when describing perceived problems or (especially) one’s adversaries — for instance, do not analogize people to Stalin, Hitler/ the Nazis, Mao, the antagonists of 1984, etc.

5. Be yourself.

At Heterodox Academy, we believe that successfully changing unfortunate dynamics in any complex system or institution will require people to stand up — to leverage, and indeed stake, their social capital on holding the line, pushing back against adverse trends and leading by example. This not only has an immediate and local impact, it also helps spread awareness, provides models for others to follow and creates permission for others to stand up as well. This is why Heterodox Academy does not allow for anonymous membership; membership is a meaningful commitment precisely because it is public.

CERTIFICATE OF ORDINATION: THIS DOCUMENT HEREBY AFFIRMS THAT WILL SWEETMAN HAS BEEN ORDAINED BY THE CHURCH OF THE LATTER-DAY DUDE ON THIS DAY MAY 20, 2019

What is Dudeism?

While Dudeism in its official form has been organized as a religion only recently, it has existed down through the ages in one form or another. Probably the earliest form of Dudeism was the original form of Chinese Taoism, before it went all weird with magic tricks and body fluids. The originator of Taoism, Lao Tzu, basically said “smoke ’em if you got ’em” and “mellow out, man” although he said this in ancient Chinese so something may have been lost in the translation.

Down through the ages, this “rebel shrug” has fortified many successful creeds – Buddhism, Christianity, Sufism, John Lennonism and Fo’-Shizzle-my-Nizzlism."fo shizzle ma nizzle" is a bastardization of "fo' sheezy mah neezy" which is a bastardization of "for sure mah nigga" which is a bastdardization of "I concur with you whole heartedly my African american brother".

-- fo' shizzle my nizzle, by Urban Dictionary

The idea is this: Life is short and complicated and nobody knows what to do about it. So don’t do anything about it. Just take it easy, man. Stop worrying so much whether you’ll make it into the finals. Kick back with some friends and some oat soda and whether you roll strikes or gutters, do your best to be true to yourself and others – that is to say, abide.

Incidentally, the term “dude” is commonly agreed to refer to all genders. Most linguists contend that the diminutive “dudette” is not in keeping with the parlance of our times.

Great Dudes in History

Pillars of Dudeism, these Dudeist prophets and peacemakers have existed throughout history.

Proud we are of all of them.

_____________

Lao Tzu, Creator of Taoism

When things got screwed up in Ancient China Lao Tzu didn’t go all Mr. Miyagi and try to fix it. He got on his buffalo and took off for more copacetic pastures. But not before scribbling down a few what-have-yous that helped define Eastern philosophy ever since.

Heraclitus, Greek Philosopher

The man who wrote “you can never step into the same river twice” propagated the idea that everything was in flux, or “burning.” Consequently one should make the most of it and spark one up whenever possible. And step into the river from time to time, preferably with a cocktail and an inner tube.

Snoopy, Charlie Brown’s Dog

Always living up to the dictum, “It’s a dog’s life,” he also famously said “My life has no purpose, no direction, no aim, no meaning, and yet I’m happy. I can’t figure it out. What am I doing right?”

Jeffrey Lebowski, The Dude

The uber-dude. Helped to bring Dudeism to the forefront of modern consciousness. If not for him, we’d still be stuck in the dude dark-ages. He’s Dude Vinci, Isaac Dudeton, and Charles Dudewin all rolled into one. Or just, His Dudeness, if you’re into that whole brevity thing.

Quincy Jones, Urban Dude/Producer/ Musician/Songwriter

Quincy Jones’ nickname was “The Dude,” and though his 70s urban cult of Dudeism is slightly different than present-day orthodox Dudeism, it still exalts the groovy over the square, the heartfelt over the phony, and the afro over the buzz-cut. At least it did until he started going bald.

Jennifer Lawrence, Angelic, yet down-to-earth-actor

Despite her endearing good looks and the undying affection of everyone on Earth, Lawrence hasn’t let stardom warp her. Deeply down to earth and often refreshingly casual, she’s also an outspoken Big Lebowski fangirl. She even played Maude in a high profile public reading of the screenplay.

The Buddha, Nepalese Sage

In keeping with the idea that the ideal Dude abandons the trappings of society and goes it his own way, there is no better candidate for Dudeism than the Buddha. Born a rich prince, he bailed on his birthright and taught that you should go with the flow. Chicks also dug him like crazy but none ever tied him down, cause Nirvana was what he was all about, man. Righteous.

Jesus Christ, Bearded prophet of the meek and early archetype of the 1960s hippie.

Jesus was born Jewish, but then converted to Dudeism after he realized that the Romans and the Pharisees were fucking fascists. Today lots of people think he’s the son of the guy who created the universe and that our life is in his hands. But probably he was just a dude who thought people should mellow out and stop getting so worked up about stuff. Sadly, few of his followers seem to actually realize that. Remember: There’s not a literal connection.

David Grayson, Alter-ego of Pulitzer-prize winning author Ray Stannard Baker

David Grayson wasn’t a real person, but no one knew that for a long time. Intellectual writer Ray Stannard Baker longed for a life out in the pastures and so wrote a series of seemingly-autobiographical books under this nom-de-dude. The series speaks of the comfort of a simple life without too much work, surrounded by nature and good friends. Baker was forced to admit the truth after the character grew in such popularity that others were claiming to be him. The dude will out. To thine own self be dude.

Jerry Garcia, Guitar canoodler extraordinaire

Roll away, the dude. Got a little carried away with the drugs, but it wasn’t because of psychic torment or weakness of character. He just liked them and maybe they made him play better. He was universally reknowned as an all-around nice guy with a live and let live attitude and appropriately-dudeish facial hair.

Joni Mitchell, Angel-voiced troubador of the unpaved

While most of the sixties rock revolution was fomented by guys, the ladies seemed to end up as notches in their frayed leather belts of free love, or dead from intemperance like Mama Cass and Janis Joplin. Not so for the quintessentially cool dudeist saint Mitchell who sang smartly about individualism while smoking and cursing like a sailor and living life on her own terms. She paints pretty good too.

Mohandas “Mahatma” Gandhi, Peace-loving subcontinental pacifist

Calmer than you are. Calmer than anyone ever anywhere. Gandhi was never, ever un-dude. He practically invented modern pacifism, not to mention shabby chic – he showed up to stuffy English parliament in nothing more than a ratty sheet. He also invented the sit-in, the hunger strike and the cool 1960s specs. He was the man in the white pajamas.

Walt Whitman, Turned the hobo zero into a boho hero

Never had anything approaching a permanent job. Wandered all over the place. Became a famous poet unexpectedly and accidentally, while poseur contemporaries like Emerson and Thoreau struggled to make sure everyone thought they were hip and bohemian. Was a literate friend to the common man, never really acknowledged his fame, and even though he was probably gay, adamantly refused to iron his clothes.

Julia Child, Brought fine cuisine to the common man

If not for Madame Julia, most Americans afflicted with a bad case of the munchies would only have overboiled 1950s cooking to turn to. But this huge, burly woman proved that you can be working-class and sloppy-looking and still eat good grub. She took the snobbery out of eating well – on one episode of her TV show she accidentally dropped food on the floor and then unceremoniously threw it back in the pan. Right on, Grey Poupon.

Jeff Spicoli, Quintessential Surfer Dude

Surfers are responsible for the resurgence of the term “dude” in the 1970s so it would be downright unholy to omit their pop culture patron saint, Jeff Spicoli, Sean Penn’s character in the 1980s movie “Fast Times at Ridgemont High.” Spicoli summed up the dude ethos in this perfectly pithy riposte to another character’s suggestion that he get a job: “What for? All I need are some tasty waves, a cool buzz, and I’m fine.” He also had the brilliant idea of ordering delivery pizza during history class. Though he almost failed history, he totally aced Dudeist Ethics 101. Radical!

Kurt Vonnegut, Modern day Dudeist philosopher

“I tell you, we are here on Earth to fart around, and don’t let anybody tell you different.” So wroteth one of the greatest writers of Dudeist novels ever. While few of his books really even had plots, they were so packed with witty, quotable sayings and iconoclastic, easygoing ideas to live by that it hardly mattered. In fact, the very idea that plots were a part of life was anathema to him. Consistently imploring the world to shrug rather than assert, his essential philosophy was that life on earth is totally and utterly nonsensical so just try to have as good a time as possible without blowing anything up. So it goes.

Have any suggestions for additional dudes? Please suggest them to us.Check out more Great Dudes in History at Abide University and The Dudespaper.

***

The Take it Easy Manifesto

by Rev. Dwayne Eutsey, Arch Dudeship

[Uncle Sam Says:] I WANT YOU TO TAKE IT EASY

THERE’S A RELIGION for its time and place…It fits right in there, helps us abide through all the strikes and gutters, the ups and downs of the whole durned human comedy. It really ties your life together.

And the religion for our time and place is Dudeism.

Of course, nihilists and reactionaries will probably dispute that—when they’re not throwing marmots into your bathtub or coffee cups at your forehead. That’s why you need to know how to respond when someone who is un-Dude asks you what the fuck you’re talking about when you tell them about Dudeism.

Now, it’s a basic tenet of the Dudeist ethos to just say “Fuck it,” or “Yeah, well, that’s just, like, your opinion, man,” when someone micturates upon our faith. But we’re talking about unchecked theological aggression here, drawing a line in the spiritual sand, Dude. Across this line you do not—also, Dude, “faith” is not the preferred nomenclature—“worldview,” please.

So, What the Fuck am I Talking About?

Lost my train of thought there. Anyway, in defending whether Dudeism is really a religion, worldview, or what-have-you, a Dudeist must first address a very basic question: What makes a religion? Is it being prepared to do the right thing, whatever the cost? Isn’t that what makes a religion? Or is it that along with a pair of testaments?

IF YOU WILL IT, DUDE, IT IS NO DREAM

Well, Dude, we just don’t know. Religion is a very complicated thing. A lotta scriptural ins, a lotta ritual outs…a lot of ecclesiastical strands to keep in your head, man. There is a lot about religion that doesn’t make a whole lot of sense to us. It can be quite stupefying, in fact. But there are some basic tools that can help put you in a unique position to confirm or disconfirm whether Dudeism is a religion.

First off, it’s good to define what in God’s holy name we’re blathering about when we say the word “religion”. A wiser fellah than myself once said that “religion” has its root in the Latin word “ligo,” or “to bind together.” That’s a good place to start, I guess, because the tenets of Dudeism do indeed bind its diverse adherents together in one big round robin.

But there are other ways that can help you explain how Dudeism is a religion, and in English, too. Here are just a couple.

All Right, Let’s Get Down to Cases

The beauty of Dudeism is its simplicity. Once a religion gets too complex, everything can go wrong.

That’s why the “To What/From What/By What Means” method of identifying a religion is a great way to summarize the Dudeist ethos for your un-Dude friends.

DUDE, THE CHINAMAN IS NOT THE ISSUE HERE. ALSO, DUDE, CHINAMAN IS NOT THEPREFERRED NOMENCLATURE. ASIAN-AMERICAN, PLEASE.

For example, if you apply this method to Buddhism (a compeer of Dudeism), you can easily answer what the point of it is.From what is Buddhism trying to liberate us? Suffering

To what state of being is Buddhism trying to bring us? Nirvana

By what means does Buddhism attempt do this? The Noble Eightfold Path.

Isn’t that fucking interesting, man? Now let’s apply it to Dudeism:From what is Dudeism trying to liberate us? Thinking that’s too uptight.

To what state of being is Dudeism trying to bring us: Just taking it easy, man.

By what means does Dudeism attempt do this? Abiding.

Now, that’s fucking ingenious, if I understand it correctly.

If You Define It, It Is a DREEMMS

But what do Dudeists believe? Well, although you have your story and I have mine, there are certain things that bring us together and root us, like the aitz chaim he, in a shared community.a common term used in Judaism. The expression can be found in Genesis 2:9, referring to the Tree of Life in the Garden of Eden. It is also found in the Book of Proverbs, where it is figuratively applied to "the Torah" Proverbs 3:18, "the fruit of a righteous man" Proverbs 11:30, "a desire fulfilled" Proverbs 13:12, and "healing tongue" Proverbs 15:4.

-- Etz Chaim, by Wikipedia

To help me clarify what I’m blathering about, I’ll use the seven dimensions of religion identified by Ninian Smart (another wiser fellah than myself): Doctrinal, Ritual, Ethics, Experiential, Myth, Material, and Social…or, in the parlance of religious studies, DREEMMS).

JUST TAKE IT EASY, MAN! THE TAKE IT EASY MANIFESTO

Doctrinal (the systematic formulation of religious teachings in an intellectually coherent form): Like Zen, Dudeism isn’t into the whole doctrinal thing; we prefer direct experience of takin’er easy, and often contemplate two indiscernible Coens to achieve that modest task.

Perhaps the closest Dudeists come to having a systematic formulation of our religious teachings is: “Sometimes you eat the bear, and, well, sometimes the bear, he eats you.” Is that some sort of Eastern thing? Far from it, Dude.

Ritual (forms and orders of ceremonies): Dudeists are also not into the whole ritual thing, but there are some things we do for recreation that bring us together, like bowling, driving around, the occasional acid flashback, listening to Creedence. Some Dudeists are shomer shabbas, and that’s cool.a person who observes the mitzvot (commandments) associated with Judaism's Shabbat, or Sabbath, which begins at dusk on Friday and ends after sunset on Saturday.

-- Shomer Shabbat, by Wikipedia

Ethics (rules about human behavior): Although this isn’t ‘Nam, there aren’t many behavioral rules in Dudeism, either. However, we do recognize that we may enter a world of pain whenever we go over the line and we are forever cognizant of what can happen when we fuck a stranger in the ass.

Experiential (the core defining personal experience): Abiding and takin’er easy.

Myth (the stories that work on several levels and offer a fairly complete and systematic interpretation of the universe and humanity’s place in it): The Big Lebowski is our founding myth; just as the Christian Gospels, based on the Jesus of history, provide a portrait of the mythical Christ of faith who “died for all us sinners,” the film, based on the Dude of history (Jeff Dowd), presents the mythical Dude of film (Jeff Bridges) who “takes it easy for all us sinners.”

Material (ordinary objects or places that symbolize or manifest the sacred or supernatural): That rug really tied the room together, did it not?

Social (a system shared and attitudes practiced by a group. Often rules for identifying community membership and participation): Racially we’re pretty cool and open to pretty much everyone…pacifists, veterans, surfers, fucking lady friends, vaginal artists, video artists with cleft assholes, dancing landlords, doctors who are good men and thorough, enigmatic strangers, brother shamuses…And proud we are of all of them.

Those we consider very un-Dude include: Rug-pissers, brats, nihilists, Nazis, human paraquats, pederasts, pornographers, fucking fascists, reactionaries, and angry cab drivers. Friends like these, huh, Gary?

I CAN HAS IT EASY?

Aw, Hell. I Done Innerduced Dudeism Enough

LIFE IS A CYCLE. SOMETIMES YOU HAVE TO GET OFF. GRANE JACKSON'S FOUNTAIN STREET THEATRE THIS TUESDAY (NOTES WELCOME)

Although Dudeists may lack three thousand years of beautiful tradition, from Moses to Sandy Koufax, we do share the great spiritual insights espoused by many great Dudes throughout the ages. As our Dudely Lama once wrapped it all up for us:“Life is short and complicated and nobody knows what to do about it. So don’t do anything about it. Just take it easy, man. Stop worrying so much whether you’ll make it into the finals. Kick back with some friends and some oat soda and whether you roll strikes or gutters, do your best to be true to yourself and others – that is to say, abide.”

Knowing that, now you can die with a smile on your face without feelin’ like the Good Lord gypped you. And that’s what Dudeism’s all about.

See ya later on down the trail.

Arch Dudeship Dwayne Eutsey is currently founding a Dudeist monastery for Irish monks: The Brotherhood ShamusThe Brotherhood Shamus: A Monastery for Private Investigations

by Rev. Dwayne Eutsey

Say what you will about the tenets of the Brother Shamus Monastic Order…at least it’s an ethos.

St. Da Fino’s Virtual Shrine of Our Special Lady is Dudeism’s first contemplative order consisting of Brother Shamuses (and special ladies) devoted to following their innermost Dude.

What is a Brother Shamus?

Like our blessed patron St. Da Fino, who set out on his quest to crack the Knudsen Conundrum, Brother Shamuses (not to be confused with Irish monks) endeavor to explore life’s most vexing mysteries.

At St. Da Fino’s Virtual Shrine of Our Special Lady, Brother Shamuses join together to dig the Dude’s work and contemplate Dudeism’s enduring questions posed by the Dudester himself, such as:

•“Who the fuck are you, man?”

•“Why the fuck *are* you following the Dude?”

•“How ya gonna keep ‘em down on the farm once they seen Karl Hungus?”

As everyone knows, there are no easy answers to these questions, and pondering them alone can sometimes cause a darkness to warsh over you, darker’n a black steer’s tookus on a moonless prairie night, as a wiser feller than myself once rambled.

Click HERE to pray!

Why Become a Brother Shamus?

It is in the dark night of our most private snoopings that we unexpectedly encounter the Dude. Like St. Da Fino on the night of his epiphany, we must answer the Dude’s call to “get out of that fucking car, man”—or, in the parlance of our times, to let go of the ego’s steering wheel—before we can ever come face to face with our deepest Dudeness.

Unless you’re adhering to a pretty strict drug regimen, though, you need compeers to help keep your mind limber enough to abide with the Dude.

Becoming a Brother Shamus through St. Da Fino’s Virtual Shrine of Our Special Lady provides you with a supportive community that pools its resources, trades information, shares professional courtesies, has some burgers, some beers, a few laughs…and what have you.

How can you become a Brother Shamus?

1. Heed first the Dude’s call to “get out of that fucking car, man.”

2. Confess that you are indeed a dick.

3. Intend to do no harm.

4. Follow the Dude’s admonition to fuck off, but without begrudging the Dude.

Once you have taken these teachings to heart, you may consider yourself a Brother Shamus. Fabulous stuff, man.

If you like, you may now make a prayer to “St. Dafino’s Virtual Shrine of Our Special Lady”. She is a good shrine, and thurrah.

THE PASSION OF THE JESUS. YOU GOT A DATE ASH WEDNESDAY, BABY

Also, please visit our Facebook Group.

Dwayne can be reached at [email protected]

In 1781–82 Antoine-Louis-Henri Polier, a Swiss Protestant who served in the English East India Company’s army until 1775, had had copies of the Vedas made for him at the court of Pratap Singh at Jaipur. 122 Polier’s intermediary was a Portuguese physician, Don Pedro da Silva Leitão. A doctor named Pedro da Silva Leitão had been present at the court of Jai Singh in 1728 and played a part in the negotiations with the Portuguese regarding the exchange of scientific knowledge, personnel, and equipment. He was long-lived, but Polier’s friend may rather have been one of his descendants. Jai Singh had assembled a substantial collection of manuscripts from religious sites across India, and in the time of his successor Pratap Singh the library had contained the saṃhitās of all four Vedas in manuscripts dating from the last quarter of the seventeenth century. 123

Although Polier records that he had sought copies of the Veda without success in Bengal, Awadh, and on the Coromandel coast, as well as in Agra, Delhi, and Lucknow and had found that even at Banaras “nothing could be obtained but various Shasters, w.ch are only Commentaries of the Baids,” he connects this not with the reluctance of the Brahmins but rather, like Bernier, with “the persecution the Hindous suffered throughout India” under Aurangzeb, noting that Jaipur had been spared because of the services rendered to the Mughal Emperor by Jai Singh.By this it may be seen how little a dependence is to be placed in the assertions of those who have represented the Brehmans as very averse to the communication of the principles of their Religion—their Mysteries, and holy books.—In truth, I have always found those who were really men of science and knowledge, very ready to impart and communicate, what they knew to whoever would receive it and listen to them with a view of information, and not merely for the purpose of turning into ridicule, whatever was not perfectly consonant to our European Ideas, tenets and even prejudices—some of w.ch I much fear are thought by the Indians to be full as deserving of ridicule as any they have.—At the same time it must be owned, that all the Hindous,— the Brehmans only excepted, are forbidden by their Religion from studying and learning the Baids—the K’hatrys alone being permitted to hear them read and expounded: This being the case, it will naturally be asked—how came an European who is not even of the same faith, to be favoured with what is denied even to a Hindou?—To this the Brehmans readily reply—That being now in the Cal Jog or fourth age, in w.ch Religion is reduced to nought, it matters not who sees or studies them in these days of wickedness. 124

It is perhaps significant that it was in a royal library, rather than in a Brahmin pathasala, that Polier found manuscripts of the Vedas. 125 But the same is not true of the manuscripts acquired in Banaras only fifteen years later by Henry Thomas Colebrooke, during the period (1795–97) when he was appointed as judge and magistrate at nearby Mirzapur: “A working scholar, he sought manuscripts that ‘had been much used & studied in preference to ornamented & splendid copies imperfectly corrected.’” 126 Moreover, in a letter to his father in February 1797 Colebrooke echoed Polier’s sentiments:I cannot conceive how it came to be ever asserted that the Brahmins were ever averse to instruct strangers; several gentlemen who have studied the language find, as I do, the greatest readiness in them to give us access to all their sciences. They do not even conceal from us the most sacred texts of their Vedas. 127

The several gentlemen would likely have included General Claude Martin, Sir William Jones, and Sir Robert Chambers. These were all East India Company employees who obtained Vedic manuscripts (Jones from Polier) in the last decades of the eighteenth century.

Why was it so much easier for Polier, Colebrooke, and others to obtain what it had been so difficult for the Jesuits and impossible for the Pietists? There are several differences in the context that might have played a part. Some are geographical: Were Brahmins in the south much more reluctant to transmit the Vedas than those in the north? Or was oral transmission more dominant—and therefore physical copies harder to come by—in the south? Others are historical, political, and economic: Is the lack of resistance encountered by Polier and Colebrooke to be explained by the significant shift in power dynamics as the English East India Company was transformed from a trading company to a territorial power? Anquetil Duperron was offered Vedas he could not afford; Le Gac was restrained by the mission’s parlous finances; but the same did not apply to the wealthy men like Martin and Polier. Finally, there are religious considerations: Did it matter—as Polier suggests—that the East India Company men were not in India to convert Hindus to Christianity?

The difficulty the Jesuits experienced in obtaining copies of the Vedas is often exaggerated. Although Bouchet had reported in 1711 that he had been unable to obtain copies of the Vedas, the reluctance of Le Gac to respond to a request for the Vedas in 1726 from his fellow Jesuit Souciet indicates that in the period after Nobili the Jesuits in India did not regard this as a priority. Le Gac did not mention Brahmin secrecy in his responses to Souciet in 1726 and 1727, but rather the likely cost and doubtful utility of obtaining manuscripts or translations of the Vedas. His attitude changed only in 1728, with the intervention of Bignon and Le Noir. From that point, it took only two years for Calmette to obtain the Ṛg and Yajur Veda saṃhitās. Despite Calmette’s statement about no European having been able to unearth this text “since India has been known,” the evidence suggests rather that no European other than Nobili had seriously sought to obtain the Vedas. The “false” Vedas obtained by the Pietists two years after Calmette—and by Gargam and Pons six years before—are explicable by the flexibility of the term Veda; we do not need to postulate either duplicity or secrecy on the part of those who transmitted these texts.

The question of the availability of the texts in manuscript form touches on the hotly debated issue of the oral transmission of the Vedas. That there was a powerful presumption against writing down Hindu texts, and the Vedas in particular, is not controversial. “One who reads from a written text” (likhita-pāṭhaka) is included among a list of the six worst types of those who recite the Vedas. 128 Nevertheless, in a survey of Vedic manuscripts, mostly of southern provenance, from c. 1650–1850, Cezary Galewicz notes the paradox of a copyist who cites this very verse in the colophon of a manuscript of 1787 containing the fourth aṣṭaka of the Ṛgveda saṃhitā. 129 Of course, the fact that manuscripts of the Vedas existed by this period does not mean that all Brahmins who knew the Vedas would have had them also in manuscript form, still less that they would have been willing to sell or to transcribe them for Europeans. We do not have to fall into what Johannes Bronkhorst calls “the brahmanical trap” 130—imagining that the Vedas were never written down—in order to accept that the brahminical prejudice against writing down the Vedas would have meant that it was far less likely that European scholars would come across manuscripts of the Vedas than manuscripts of other texts. 131 But the Vedas did exist in manuscript, and Calmette’s “hidden Christians” found there were also Brahmins prepared to part with, or to produce, manuscripts—even if they thought they were doing so only for other Brahmins.

Europeans were first able to acquire Hindu texts, in the 1540s and 1550s, because of Portuguese control in Goa. The extension of the English East India Company’s territorial and military might in the later part of the eighteenth century would have changed the nature of interactions between Europeans and Indians elsewhere. 132 Colebrooke’s experience in Mirzapur is perhaps the clearest instance of the effect of a shift in power dynamics, but Polier’s success at the court of Pratap Singh in 1781—not yet within the direct ambit of British power—seems to owe more to the character of the court. Since the time of Jai Singh in the 1720s, the court at Jaipur had been involved in the exchange—partly mediated by Jesuits—of materials of scientific and scholarly interest with the Portuguese court. In 1734 Jai Singh invited Jean-François Pons and Claude Boudier, French Jesuits stationed in Bengal, to Jaipur. 133 Pons was also engaged in collecting manuscripts for Bignon, and had their trip not been cut short by illness it seems likely he would have preceded Polier in gaining access Jai Singh’s collection of Sanskrit manuscripts.

-- The Absent Vedas, by Will Sweetman

-- J.R. "Bob" Dobbs

Discordianism is a paradigm based upon the book Principia Discordia, written by Greg Hill with Kerry Wendell Thornley in 1963, the two working under the pseudonyms Malaclypse the Younger and Omar Khayyam Ravenhurst. According to self-proclaimed "crackpot historian" Adam Gorightly, Discordianism was founded as a parody religion. Many outside observers still regard Discordianism as a parody religion, although some of its adherents may utilize it as a legitimate religion or as a metaphor for a governing philosophy.

The Principia Discordia, if read literally, encourages the worship of the Greek goddess Eris, known in Latin as Discordia, the goddess of disorder, or archetypes and ideals associated with her. Depending on the version of Discordianism, Eris might be considered the goddess exclusively of disorder or the goddess of disorder and chaos. Both views are supported by the Principia Discordia. The Principia Discordia holds three core principles: the Aneristic (order), the Eristic (disorder), and the notion that both are mere illusions. Due to these principles, a Discordian believes there is no distinction between order and disorder, since they are both man-made conceptual divisions of the pure element of chaos. An argument presented by the text is that it is only by rejecting these principles that you can truly perceive reality as it is, chaos.

It is difficult to estimate the number of Discordians because they are not required to hold Discordianism as their only belief system, and because, by nature of the system itself, there is an encouragement to form schisms and cabals.

-- Discordianism, by Wikipedia

By this time, other manuscripts of the Vedas had been obtained in India. In 1781–82 Antoine-Louis-Henri Polier, a Swiss Protestant who served in the English East India Company’s army until 1775, had had copies of the Vedas made for him at the court of Pratap Singh at Jaipur. Polier’s intermediary was a Portuguese physician, Don Pedro da Silva Leitão. A doctor named Pedro da Silva Leitão had been present at the court of Jai Singh in 1728 and played a part in the negotiations with the Portuguese regarding the exchange of scientific knowledge, personnel, and equipment. He was long-lived, but Polier’s friend may rather have been one of his descendants. Jai Singh had assembled a substantial collection of manuscripts from religious sites across India, and in the time of his successor Pratap Singh the library had contained the saṃhitās of all four Vedas in manuscripts dating from the last quarter of the seventeenth century….

Polier records that he had sought copies of the Veda without success in Bengal, Awadh, and on the Coromandel coast, as well as in Agra, Delhi, and Lucknow and had found that even at Banaras “nothing could be obtained but various Shasters, w.ch are only Commentaries of the Baids”…

--The Absent Vedas, by Will Sweetman

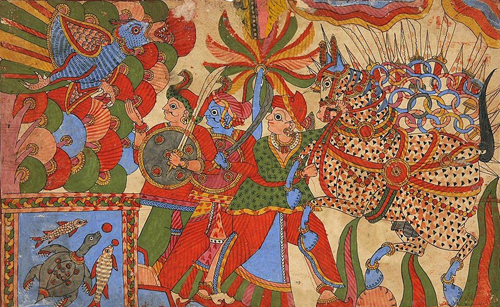

The Ashvamedha (Sanskrit: अश्वमेध aśvamedha) is a horse sacrifice ritual followed by the Śrauta tradition of Vedic religion. It was used by ancient Indian kings to prove their imperial sovereignty: a horse accompanied by the king's warriors would be released to wander for a period of one year. In the territory traversed by the horse, any rival could dispute the king's authority by challenging the warriors accompanying it. After one year, if no enemy had managed to kill or capture the horse, the animal would be guided back to the king's capital. It would be then sacrificed, and the king would be declared as an undisputed sovereign.

The best-known text describing the sacrifice is the Ashvamedhika Parva (Sanskrit: अश्वमेध पर्व), or the "Book of Horse Sacrifice," the fourteenth of eighteen books of the Indian epic poem Mahabharata. Krishna and Vyasa advise King Yudhishthira to perform the sacrifice, which is described at great length. The book traditionally comprises 2 sections and 96 chapters. The critical edition has one sub-book and 92 chapters.

The ritual is recorded as being held by many ancient rulers, but apparently only by two in the last thousand years. The most recent ritual was in 1741, the second one held by Maharajah Jai Singh II of Jaipur. The original Vedic religion had evidently included many animal sacrifices, as had the various folk religions of India. Brahminical Hinduism had evolved opposing animal sacrifices, which have not been the norm in most forms of Hinduism for many centuries. The great prestige and political role of the Ashvamedha perhaps kept it alive for longer.

The Ashvamedha could only be conducted by a powerful victorious king (rājā). Its object was the acquisition of power and glory, the sovereignty over neighbouring provinces, seeking progeny and general prosperity of the kingdom. It was enormously expensive, requiring the participation of hundreds of individuals, many with specialized skills, and hundreds of animals, and involving many precisely prescribed rituals at every stage.

The horse to be sacrificed must be a white stallion with black spots. The preparations included the construction of a special "sacrificial house" and a fire altar. Before the horse began its travels, at a moment chosen by astrologers, there was a ceremony and small sacrifice in the house, after which the king had to spend the night with the queen, but avoiding sex.

The next day the horse was consecrated with more rituals, tethered to a post, and addressed as a god. It was sprinkled with water, and the Adhvaryu, the priest and the sacrificer whispered mantras into its ear. A black dog was killed, then passed under the horse, and dragged to the river from which the water sprinkled on the horse had come. The horse was then set loose towards the north-east, to roam around wherever it chose, for the period of one year, or half a year, according to some commentators. The horse was associated with the Sun, and its yearly course. If the horse wandered into neighbouring provinces hostile to the sacrificer, they were to be subjugated. The wandering horse was attended by a herd of a hundred geldings [castrated horse, or donkey or mule], and one or four hundred young kshatriya men, sons of princes or high court officials, charged with guarding the horse from all dangers and inconvenience, but never impeding or driving it. During the absence of the horse, an uninterrupted series of ceremonies was performed in the sacrificer's home.

After the return of the horse, more ceremonies were performed for a month before the main sacrifice. The king was ritually purified, and the horse was yoked to a gilded chariot, together with three other horses, and Rigveda (RV) 1.6.1,2 (YajurVeda (YV) VSM 23.5,6) was recited. The horse was then driven into water and bathed. After this, it was anointed with ghee by the chief queen and two other royal consorts. The chief queen anointed the fore-quarters, and the others the barrel and the hind-quarters. They also embellished the horse's head, neck, and tail with golden ornaments. After this, the horse, a hornless he-goat, and a wild ox (go-mrga, Bos gaurus) were bound to sacrificial stakes near the fire, and seventeen other animals were attached to the horse. A great number of animals, both tame and wild, were tied to other stakes, according to one commentator, 609 in total. The sacrificer offered the horse the remains of the night's oblation of grain. The horse was then suffocated to death.

The chief queen ritually called on the king's fellow wives for pity. The queens walked around the dead horse reciting mantras. The chief queen then had to spend a night with the dead horse.

On the next morning, the priests raised the queen from the place. One priest cut the horse along the "knife-paths" while other priests started reciting the verses of Vedas, seeking healing and regeneration for the horse.