by Karl E. Meyer and Shareen Blair Brysac

© 1999 by Karl E. Meyer and Shareen Blair Brysac

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

CHAPTER ELEVEN: Emissary to the White Tsar

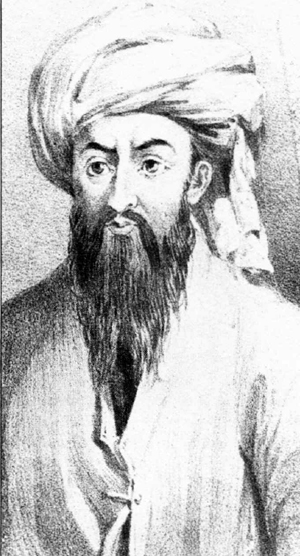

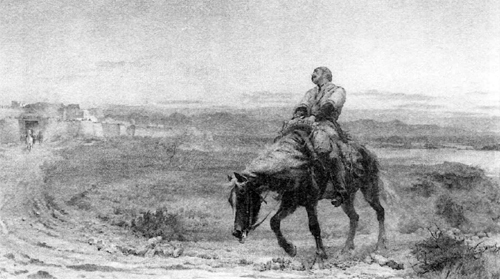

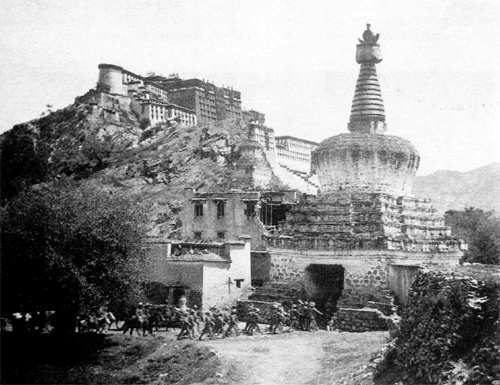

FEW FIGURES OF IMPORTANCE IN THE IMPERIAL DUELS OF Central Asia have been so commonly misrepresented as Agvan Dorzhiev (1854-1938), the Buddhist lama and Russian subject who fought long and worthily for Tibetan nationhood. It was his presence that brought British bayonets to Lhasa in 1904, an event whose magnitude required a suitable provocation. So Dorzhiev "was elevated to the position of Evil Genius at the Court of the Dalai Lama, two parts Rasputin to one part Macavity the Mystery Cat," in the apt phrase of Patrick French, the biographer of Sir Francis Younghusband, leader of the Tibetan expedition. Indeed Dorzhiev in one of his aspects was Macavity. When he so wished, he left no tracks. It did not help his cause.

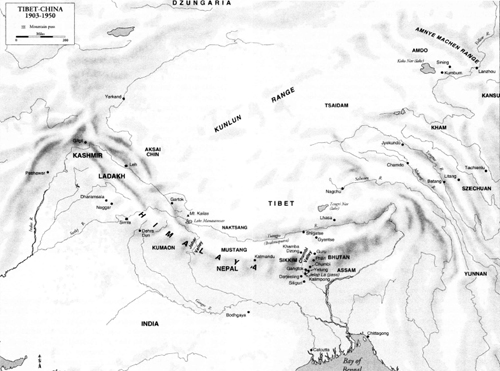

At least three times Dorzhiev passed invisibly through India, slipping over frontiers and eluding police scrutiny while a guest at Buddhist monasteries, but his appearances at the Russian court were not secret-they were announced in the press. For Lord Curzon, the Viceroy of India, angered and humiliated by lapses of his intelligence service, the import was plain. Tibet was supposedly closed to foreigners, and the Dalai Lama returned unopened urgent messages from Curzon. Yet here was a presumed Russian agent commuting across the Himalaya, lending substance to reports that the Tsar had already signed a secret pact with China to allow Russian officials and mining engineers into Tibet. "I am myself," Curzon wrote in 1902 to the Foreign Secretary in London, "a firm believer in the existence of a secret understanding, if not a secret treaty, between Russia and China about Tibet; and, as I have said before, I regard it as a duty to frustrate their little game while there is still time."

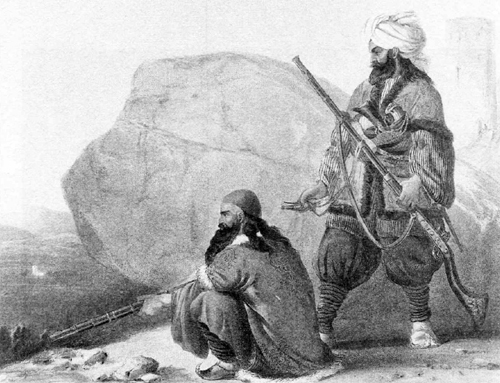

Was there really a "little game"? It cannot be ruled out. The British themselves prompted its initial moves. In 1868, the Journal of the Royal Geographical Society published the first in a series about Tibet based on clandestine visits by Indian pundits posing as pilgrims. This "cunning enterprise" was noted with keen interest in St. Petersburg by the military-scientific section of the General Staff, writes the Russian scholar Alexandre Andreyev. Among the many nationalities in the Russian Empire were several groups of Mongolians -- a potential indigene cadre for similar forays. In recently opened archives, Dr. Andreyev found that as early as 1869 the Imperial Geographical Society and the General Staff tried to recruit the Russian equivalent of pundits among Buriats and Kalmyks.

The Buriats were a Mongolian people who for centuries lived near Lake Baikal in Eastern Siberia. Revered as the "Holy Sea" or "Blue Miracle," the lake is a natural wonder nonpareil. It is the earth's deepest body of fresh water, filling an abyss fifty miles wide, 250 miles long, and more than a mile deep, with a surface area (12,162 square miles) bigger than Belgium. Near its shores the Buriats tended their livestock, pursuing a nomadic life that persisted after their conversion in the seventeenth century from shamanism to Tibeto- Mongolian Buddhism. The Kalmyks, also Mongolians by virtue of language, culture, and appearance, belong to a clan that migrated circa 1632 from Dzungaria in Central Asia to the lower Volga region. Renowned for their horsemanship, Kalmyk warriors joined Cossack cavalry regiments and fought so well against Napoleon that Alexander I awarded them a fertile domain whose revenues were to be used for schools and hospitals. Protected by royal favor, the Kalmyks adhered to Buddhism and looked to Lhasa as their Holy City-ideal potential recruits for Tsarist secret services.

Andreyev found that in 1869 a senior officer on the Imperial General Staff proposed sending a Buriat, Naidak Gomboev, as part of a religious delegation of pilgrims who eventually proceeded to Tibet in 1873. What came of this plan is unclear. Mysteriously, key prerevolutionary fiIes relating to Tibet are still missing in the archives of post-Soviet Russia. But it appears that Agvan Dorzhiev was among the pilgrims who made their way to Lhasa, so that a connection with the General Staff is not implausible. Even so, the core question is how Dorzhiev viewed his own role, and what his purposes were -- and on this, the record seems clear. Far from being a Russian agent, Dorzhiev saw himself as Tibet's emissary to the White Tsar. His purpose was to create a Tibetan-Mongolian federation in collaboration with Russia. As events dictated, he changed his tactics. Dorzhiev continued to pursue the same goal in Bolshevik times, and did so until his death in Stalin's Gulag. A learned monk as well as statesman, a tutor to the Dalai Lama, Dorzhiev was among the first to acquaint the West with the rich traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. His influence reached the United States. He was the "root lama" to Geshe Wangyal, who in 1955 resettled in Freehold Acres, New Jersey, and there founded what was to be the first Tibetan Buddhist monastery open to Americans.

If Dorzhiev had realized his dreams for Tibet and Mongolia, he might well have won a niche beside Gandhi, Sun Yat-sen, and Thomas Masaryk in the pantheon of nation-builders and freedom-seekers. Regrettably for the people he championed, it was not to be.

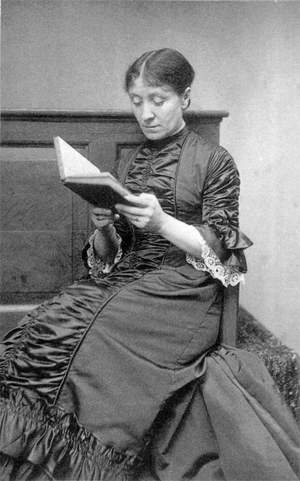

GHOOM MONASTERY, NEAR DARJEEUNG, WAS THE UNMONITORED way station to India for monks and mystics. Here in 1885-87 Madame Blavatsky, the founder of Theosophy, met Sarat Chandra Das, the pundit who covertly explored Tibet for the British. Years later, Madame's American disciple, Colonel Olcott, stopped at Ghoom, where he was given (as he describes in Old Diary Leaves), a white silken scarf that the Panchen Lama presented to Das during the pundit's stay in Tashilhunpo. Das also gave the Colonel rare Tibetan texts that were forwarded to Madame. Subsequently, having founded the Buddhist Text Society in Bengal, Sarat Chandra Das invited Olcott to address its first general meeting. In an intricate feat of deduction, K. Paul Johnson, a scholarly explorer of the esoteric tradition, maintains in The Masters Revealed (1994) that among the real-life models for Madame Blavatsky's Tibetan Masters were Das and his fellow pundit Ugyen Gyatso, along with their Tibetan patron, Losang Palden, the chief minister of the Panchen Lama.

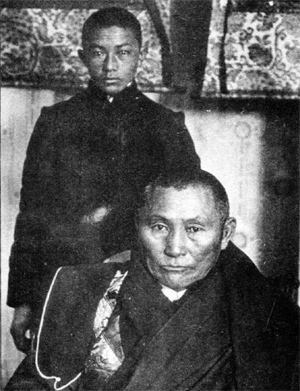

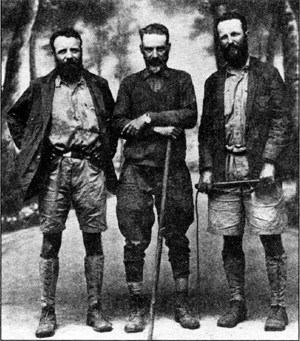

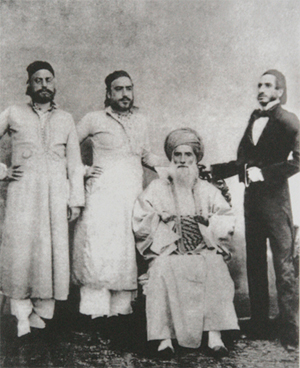

In 1900, British police questioned Das about a mysterious Buriat and a Kalmyk who had recently visited Ghoom. The monks were guests of the Mongolian abbot, Sherab Gyatso. Like Das and Ugyen Gyatso, the abbot was a British agent, and like them received 55 rupees a month for supplying information on suspicious visitors. In their responses, all three agents were "economical with the truth." The Buriat was Agvan Dorzhiev, then one of seven teachers of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, and the Kalmyk was his companion, Ovshe Norzunov.

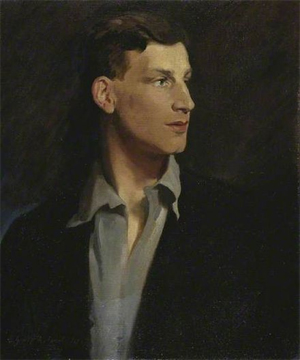

Dorzhiev was not someone easily lost in a crowd; he had the manner of command and a calm but determined gaze. Born of devout parents in remote Buriatia, schooled in a local datsan or Buddhist monastery, Dorzhiev early on showed a facility for languages, especially Tibetan, the difficult lingua franca of lamaism. At fourteen he set off for Urga, the Mongolian capital, to continue his studies, and five years later traveled to Tibet with his tutor, the Great Abbot Penden Chomphel, just possibly, as Andreyev speculates, at the behest of the Russian General Staff.

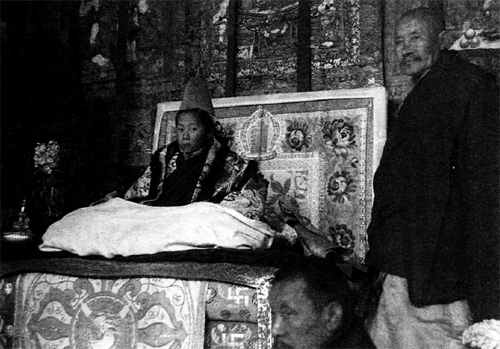

In a memoir written around 1924, Dorzhiev asserts that he set off for Tibet, via Alasha, Kumbum, and Koko Nor, together with the Mongolian princes and lamas, dispatched to accompany there the eighth reincarnation of the Urga Khutuku, the Grand Lama of Mongolia. Dorzhiev wished to remain in Lhasa but was refused permission on the grounds he was a prohibited "foreign European." Unfazed and persistent, he appealed his case, and eventually was permitted, in 1880, to enroll in one of the seminaries at Drepung, the largest Tibetan monastery, where he earned the Buddhist equivalent of a doctorate of metaphysics. So completely did Dorzhiev dispel suspicion that after the enthronement of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama he joined the inner curia, initially as the Work Washing Abbot, whose duty it was to sprinkle saffron-scented water on His Holiness. So taken was the young pontiff with Dorzhiev that when the Thirteenth attained his majority in 1895, the outsider from Siberia became his chief political adviser.

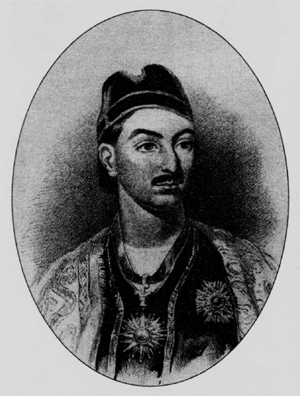

Nga-Wang Lopsang Tupden (Thupten) Gyatso (1876-1933), the Great Thirteenth Dalai Lam.a,was the first Incarnation in more than a century who actually ruled. His four predecessors passed away before coming of age, their demise reputedly assisted by their Regents, a circumstance not unwelcome to the Ambans, the representatives of China in Lhasa, who preferred childish god-kings. The Thirteenth survived, having taken the precaution of putting his own Regent under house arrest, and his reign lasted almost four decades. He strove to end Tibet's Chinese bondage and did win de facto independence though not recognized statehood. "His courage and energy were inexhaustible," writes his friend and biographer, Sir Charles Bell. "He recoiled from nothing."

The search for the Thirteenth followed the usual practice. When a Dalai Lama "retires to the heavenly fields," the oracles at Nechung and Samye provide clues to the whereabouts of the next incarnation or tulku. A council of lamas carries out the search. To prevent powerful nobles from adding to their privileges, the Dalai Lama was customarily chosen from a peasant family. Besides the appropriate physical signs, like long ears and tiger skin marks on his legs, the candidate must recognize the possessions of his predecessor, such as the dorje, a ritual object shaped like a dumbbell, connoting the thunderbolt of the Hindu god Indra. When high lamas verified that the spirit of the Twelfth had passed into the three-year-old Thirteenth, the news was transmitted to Peking and after his confirmation by the Manchu Emperor, the young boy was ceremoniously enthroned.

During the Dalai Lama's minority, a Regent, himself a tulku, was chosen by a National Assembly, composed primarily of monks, and the Kashag, or cabinet, consisting of three laymen and one monk, nearly all from noble families. But real power lay with the monasteries and their puissant abbots. As much as a third of the male population joined Buddhist orders, and of these as many as fifteen percent were "fighting monks," armed and rebellious. When they descended on Lhasa and terrorized the populace, they had to be quelled by the Dalai Lama's own troops. Nor did they eschew politics. The enormous monasteries nearest Lhasa, Drepung, Sera, and Ganden, were particularly troublesome. The Chinese, realizing their power, sought monastic support by lavishing quantities of "presents." Complicating matters was the role of the Chinese Resident or Amban, who took sides in internal politics.

At the center of this labyrinth, ensconced in the immense Potala, was the Dalai Lama, plus his parents and siblings, newly ennobled and frequently meddlesome. Tibet in 1895 was an outlying province of a crumbling Chinese Empire, whose Manchu rulers had been humiliated only that year in a disastrous war with Japan. Peking was too weak, too corrupt, and too remote to defend Tibet against "the powerful elephants from the south," the British. For their part, the British were frustrated in their negotiations with Peking and Lhasa. In 1885, the British obtained Chinese permission to send a mission from India to Tibet, only to have the project vetoed by Lhasa. As compensation, Peking was obliged to recognize British annexation of Upper Burma. This followed a clash concerning the ill-defined status and frontiers of Sikkim, over which China and Tibet both claimed authority. To enforce their own claims, the British destroyed a frontier fort and routed a Tibetan force, causing the Amban to proceed to the disputed border and negotiate directly with the Indian Foreign Secretary. The resulting 1890 treaty defined a border, acknowledged British control of Sikkim, and provided for opening a British trade mart within Tibet. Yet when the Government of India tried to open that mart, Tibetans objected, insisting China had no right to negotiate in their name. Protests caromed from Lhasa to Peking, and exasperated British officials suspected that China covertly encouraged Tibetan obduracy.

Such was the setting when Dorzhiev advised the youthful Dalai Lama to seek the protection of the White Tsar.[i] The Buriat played skillfully on the fears of his monastic brethren, who had been warned by the Chinese that the British wished to abolish lamaism, and who feared the trade mart would open the way for missionaries. In his memoir, Dorzhiev recalls the advice he gave to Tibetan high lamas. When the question of seeking help from foreign Christians arose, he said, "because Russia is the enemy of Great Britain, she will come to the assistance of the Land of Snows to prevent her being devoured." Under the White Tsar's tolerant rule, he maintained, "the pure teachings of the Buddha flourished among the Torgut [Kalmyks] and the Buriats." He reminded them that the Tsarevich passed through Buriatia on his Asian Grand Tour, bestowing favors on its inhabitants. Dorzhiev cited the legend of Shambhala, which he located somewhere in Russia, and explained that Nicholas II was also an incarnation. "Such a Bodhisattva-tsar," he said, "could also bestow favors on Tibet." As if to confirm Dorzhiev's prescience, in 1890 a French expedition led by the Central Asian explorer Gabriel Bonvalot and the Due de Chartres's eldest son, Prince Henry of Orleans, appeared on Tibet's borders. Stopped north of Lhasa by Tibetan officials, the Chinese Amban, and an armed escort, the Prince (according to Dorzhiev's memoir) urged Tibetans to befriend the French and Russians, "the strongest powers in the world," who had recently become allies. This coincided with the statement by the omniscient Nechung Oracle that spoke of a prince: "An emanation of a Bodhisattva [seemingly d'Orleans but possibly the Tsar] is in the North and East." The oracle also pointedly repeated a pungent proverb, "Even dog fat can be good for a wound."

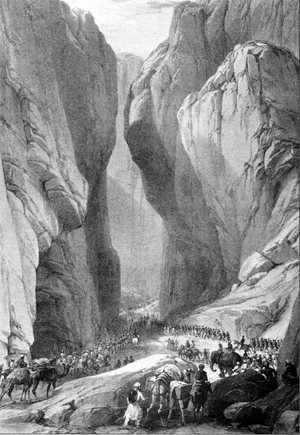

It was therefore determined that Dorzhiev should go to Russia, a momentous decision since no Dalai Lama had ever appealed to foreign Christians. Even if he failed to obtain the White Tsar's help, the Lhasa authorities reasoned, Dorzhiev could call attention to Tibet's plight. In 1898, wearing the thumb-ring of the Nechung Oracle for good luck, Dorzhiev and two companions set out for St. Petersburg via India. He traveled as a Mongol claiming Chinese citizenship, using a passport provided by the Amban in Lhasa. When the party was challenged by a suspicious Tibetan border guard, a bribe and three prostrations eased its passage.When stopped by British police at the Indian frontier, Dorzhiev showed his Chinese passport, persuading them that although he was Mongolian, he was a Chinese citizen who had "decided to return to his homeland by the easier sea route." Finally, after pausing near Darjeeling, the party boarded a train bound for Calcutta.

Buddhism originated in India, and the pilgrims visited Bodhgaya in Bihar, where Buddha attained enlightenment while sitting under the Bodhi tree. From Calcutta, they continued by sea to Peking. Finally, on reaching his old home in Buriatia, Dorzhiev received the essential letter from Prince Esper Ukhtomsky (1861-1921) inviting him to St. Petersburg.

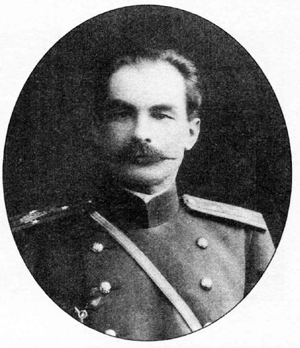

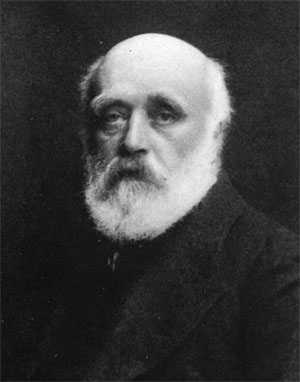

Prince Ukhtomsky was the logical intermediary. He had spent most of 1886 studying "the Lamaist question," reporting on conflicts between the proselytizing Orthodox missionaries and the Buriats. Traveling incognito, he visited the Buriats and their datsans, and conferred with their clergy in Urga and Peking. Unlike Przhevalsky, the apostle of the carbine and whip, Ukhtomsky did not belittle Asian cultures, and instead approached Buddhism and Islam with sympathetic curiosity. As to missionaries, the Prince ventured the skeptical notion that their conversions were often the result of bribes.

Ukhtomsky himself leaned to the mystical, and as a student of Theosophy, the occult, and esoteric Buddhism, he was increasingly drawn to the "luminous realms" of Asia "where hatreds and the fraternal quarrels among nations dissolve before the divine power." He believed fervently, as Schimmelpenninck van der Oye has documented, that the Buriats were a central element of Russian policy in the East. "Trans-Baikalia is the key to the heart of Asia, the vanguard of Russian civilization on the frontier of the 'Yellow Orient,'" he remarked. Thousands of lamaists made annual pilgrimages to Mongolia and Tibet, bringing into "this Asiatic wilderness" ideas of the White Tsar, and these non-Slavs would be drawn to the giant Russian Empire "not by cruelty but by kindness."

In 1895 Ukhtomsky found a new platform as editor of the St. Petersburg News, and in its columns he published his most celebrated sentence, seized upon ever since by Russophobes: "Properly speaking, in Asia we have not, nor can we have, any bounds, except the boundless sea breaking on her shores." Since Russia was on a "higher spiritual plane" than Britain, the Prince felt, there was no need to emulate its crude brand of imperialism, which was merely a cover for commercial exploitation. Russia had no reason to employ force since "it could depend mainly on benevolence to fulfill its manifest destiny." All of this was divinely ordained, and would occur through "some process of natural fusion." He criticized British India for its "exotic mushroom universities and expensive administrative reforms carried out with all the blind energy of self-sufficient ignorance," and scoffed at the irony lurking "in such cheap catchwords as 'native congresses,' 'a free native press,' 'the right of natives to be citizens of a great colonial empire.'" Russia offered the antidote to the evils of Western imperialism: the more the East was exploited, "the brighter becomes the name of the White Tsar." Largely forgotten today, his editorials were viewed in London, Berlin, and Paris as litmus words on Russia's Far Eastern policies.

WORKING WITH PRINCE UKHTOMSKY WASAN EQUALLY INTERESTING figure, Zhamsaran (Pyotr Aleksandrovich) Badmaev (1851- 1919). A fashionable practitioner of Tibetan medicine and an adviser on Mongolian affairs to the Russian Foreign Ministry, he was also the most influential Buriat in St. Petersburg. When Badmaev converted to Orthodox Christianity, none other than Alexander III acted as his godfather at the ceremony. Yet it was his Tibetan medicine that won him access to the Romanov court. In his laboratory he prepared an entire pharmacopoeia of alchemic remedies, "infusions of asoka flowers," "Nienchen balsam," "black lotus essence," "nikrik powder," and the "Tibetan elixir of life," which he prescribed for Petersburg's upper classes. Eventually, he would be summoned to treat the hemophiliac Romanov heir, Alexis. It was also whispered that he successfully treated the Tsar for a stomach ailment with a mixture of henbane and hashish -- "the effects of which were marvelous." Although some thought his presence sinister, according to James Webb, an historian of the occult, Badmaev "stood head and shoulders above the crowd of magi and holy fools who clamored around the steps of the throne."

Among those seeking his herbal pills and potions was the Finance Minister, Sergei Witte (1849-1915). The prime architect of Russia's forward policy in East Asia and godfather of the Trans-Siberian Railway, Witte wrote approvingly in his memoirs of Badmaev's plan to construct a 3,500-mile spur to the already overlong railroad. Although Alexander III was skeptical about the project, dismissing it as "all so new, strange, and fantastic," Witte's enthusiasm swayed the Government. In 1893, it advanced two million rubles to P.A. Badmaev and Co. to extend the railway from Irkutsk on Lake Baikal to the Chinese city of Lanzhou across the Gobi Desert. Ostensibly, the new line would help expand Russian trade in Central Asia.

The deeper motive was to provide a commercial cover for thousands of Buriat infiltrators who then could foment a pro-Russian revolt against the Manchu Dynasty. The resulting territorial gains would make possible a Pan-Buddhist confederacy in Central Asia under the White Tsar. Count Witte, then the dominant figure in Russian politics, supported the plan, which comported with his own grand design: "From the shores of the Pacific and the heights of the Himalayas, Russia would dominate not only the affairs of Asia but those of Europe as well." Or, as he put it in a confidential note to Nicholas II: "Given our enormous frontier with China and our exceptionally favorable situation, the absorption by Russia of a considerable part of the Chinese Empire is only a matter of time."

When Badmaev became aware of his compatriot Dorzhiev's influence in Lhasa, he was quick to sense new opportunities for employing Buriats and Kalmyks. "I am training young men in two capitals -- Peking and Petersburg-for further activities," Badmaev informed the Tsar. By 1895, Tibetan reluctance to entertain foreign Buddhists had been somewhat overcome, and Badmaev's Buriat emissaries were apparently entertained in Lhasa by none other than Dorzhiev himself. The intelligence they gathered was so highly regarded that Nicholas II bestowed gold medals on two of Badmaev's Buriat agents, Ochir Jigjitov and Dugar Vanchinov. In appreciation for his hospitality, Dorzhiev received a gold watch inscribed with the imperial monogram, which he collected on his visit to Buriatia in 1898.

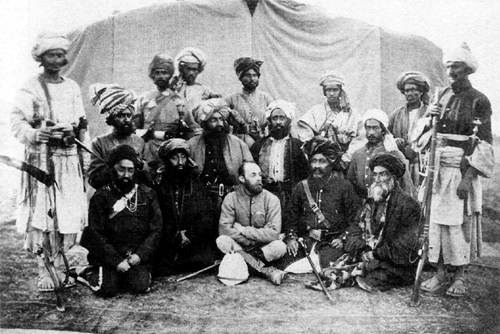

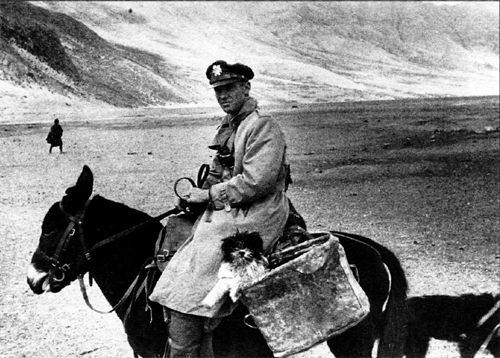

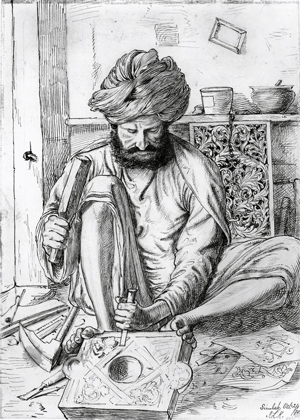

The most successful of Badmaev's proteges was Gombodjab Tsybikov (1873-1930), a leading member of the Buriat intelligentsia and a teacher at the Oriental Institute in Vladivostok. Tsybikov was at one level a Russian agent, but like Dorzhiev, as the historian Robert Rupen points out, in working for a Greater Mongolian State he was also a nationalist who later came into conflict with Soviet authorities. In a mission for the Imperial Geographical Society, Tsybikov succeeded in entering Tibet from Amdo traveling as a Buddhist pilgrim. In 1900-1901, he visited not only Lhasa but a number of monasteries. Using his camera surreptitiously, he returned to Russia with a portfolio of photographs, including some of the earliest of Lhasa, along with a bundle of Tibetan texts, earning him the Geographical Society's Przhevalsky Medal. He also provided notes on Tibet's government and population, the size of the standing army and the Chinese garrison, the practice of polygamy and polyandry, and the independent position of women.

As to Badmaev's ambitious railway scheme, nothing came of it save for the loss of the two million rubles advanced to his company. Nonetheless, Badmaev retained his mansion on the Vyborg road and his position at court, where he advised the Tsar not only on medical matters but on politics. Rasputin's biographer, Rene Fulop-Miller, asserts that Badmaev's files combined medical and encoded political data. In any case, before his death in 1919, the obscure Buriat doctor transformed a small Tibetan pharmacy into a great sanitarium, and spawned a homeopathic dynasty whose cures are today available on the Internet.

HAVING PROMOTED BADMAEV AT COURT, UKHTOMSKY NOW BECAME Dorzhiev's principal sponsor. Through the Prince's mediation, the lama appears to have met with the Tsar at Peterhof, his palace on the Gulf of Finland. By this time, the once shy and sensitive Tsarevich was the Autocrat of All Russia. Yet after reigning four years, Nicholas still disdained politics, hated confrontation, and had difficulty asserting himself. He was bullied by his uncles and, as his Empire veered from crisis to crisis, browbeaten by his wife, the Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna. His cousin, Grand Duke Alexander Mikailovich, recalls in his memoirs that the slightly undersized Nicholas dreaded being alone with his outsized uncles: "the instant the door of his study closed to outsiders -- down on the table would go with a bang the weighty fist of Uncle Alexis ... two hundred and fifty pounds packed in the resplendent uniform of Grand Admiral of the Fleet Uncle Serge and Uncle Vladimir developed equally efficient methods of intimidation ... They all had their favorite generals and admirals ... their ballerinas desirous of organizing a 'Russian season' in Paris; their wonderful preachers anxious to redeem the Emperor's soul... their clairvoyant peasants with a divine message." The Tsar's irresolution caused his War Minister, General Vannovsky, to lament that he "takes counsel from everyone: with grandparents, aunts, mummy and anyone else; he is young and accedes to the view of the last person to whom he talks." Still, it should be noted that Witte, who preferred Alexander to his son, asserts in his memoirs that Nicholas "has a quick mind and learns easily. In this respect he is far superior to his father."

Into these murky waters waded the emissary of the Dalai Lama. No official account of the lama's audience with the White Tsar has turned up -- the Russian archives are silent on the matter so we have only Dorzhiev's own recollection: "When I talked with him [Nicholas II] about Tibet, he told me how Russia would help Tibet not to be lost to enemy hands." When the Tsar consulted with his Foreign Minister, Count Lamsdorff, his War Minister, General Kuropatkin, and his Finance Minister, Witte, they suggested through Ukhtomsky that a Russian official be sent to Lhasa. Dorzhiev replied: "Definitely do not send a European. The nobles, ministers, ordinary monks and lay people have made an oath not to allow them. For the moment, there is no way to send anyone." If the Tibetans allowed Russians in Lhasa, other Europeans would not be far behind. Dorzhiev relates that "this made him [the Tsar] a little displeased." As to Russian help in countering the British and Chinese, the Tsar asked "to receive the request officially in written form" from the Dalai Lama. On both sides, the meeting fell short of expectations, but a dialogue had opened between Lhasa and St. Petersburg.

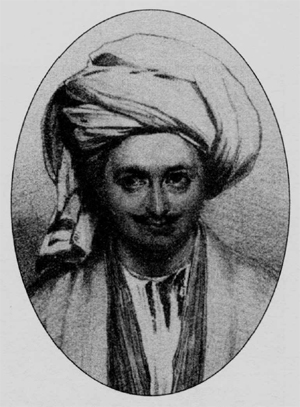

From St. Petersburg, Dorzhiev traveled south to the lower Volga, where he sought to renew and strengthen ties between the geographically separated Kalmyk and Central Asian Buddhists. There he met Ovshe Muchkinovich Norzunov (born ca. 1874), whom we have met as the other invisible guest at Ghoom monastery. An educated Kalmyk from the province of Stavropol, Norzunov was to become Dorzhiev's steadfast lieutenant.

Dorzhiev continued his "sondage politique," traveling to Paris in quest of further allies. His Russian friends introduced him to the anthropologist and Buddhist scholar Joseph Deniker, and through the professor he met a number of French notables interested in Buddhism, including Georges Clemenceau and (it would appear) Alexandra David-Neel, a devotee who by sheer grit later made her way to Lhasa. At the Musee Guimet, Dorzhiev conducted a lamaist ceremony, which was translated by Buddha Rabdanov, an eminent Buria t-- and recorded on wax cylinders. While in Paris, Dorzhiev purchased a phonograph and cylinders, as well as photographic equipment.

On his return to Russia, Dorzhiev was reunited with Norzunov, who, it was now agreed, would attempt a pilgrimage to Lhasa. The two traveled to Urga, Mongolia's capital, then separated as the Kalmyk headed toward Tibet. Norzunov passed as a Mongolian pilgrim until his caravan crossed the Gobi, when, after being halted by Kurluk Mongols, he was discovered to be a Russian. His accent and the European jacket beneath his fur garment gave him away.A bribe sufficed to satisfy the Kurluks, who guided him part of the way to Nagchu, where he eluded the Tibetan border guards who had earlier blocked Przhevalsky. Braving March gales, Norzunov arrived safely in Lhasa and there presented the Dalai Lama with a letter from Dorzhiev "describing in detail the greatness of the Russian people, the critical situation of China and expressing the opinion that the connection with Russia promises a great future for Tibet."

After six weeks in Lhasa, Norzunov headed home, following the favored route through Darjeeling, Calcutta, Peking, and Urga, arriving in Russia in August 1899. He bore an urgent summons to Dorzhiev to return as soon as possible to Lhasa, where the emissary was received by the Dalai Lama "with trust and charity." At the Great Lhasa Chanting ceremony, tens of thousands witnessed Dorzhiev's presentation to the Dalai Lama of diamonds, silks, and silver ingots cast as horseshoes, some of them gifts of the White Tsar. Dorzhiev wisely took care to provide the monasteries with their portion of Russian largesse.

Even so, the Buriat's successes, and his new rank as Senior Abbot, provoked murmurs of envy and displeasure. According to Deniker, some were scandalized by a photograph of Dorzhiev with a Russian lady. He was forced to destroy the photographic equipment-considered demonic by the monks -- that he had brought from Paris. In the pontiff's court, according to Dorzhiev's memoirs, dissension had become open and bitter:

In those times, the influential people of Tibet had these things to say about politics. Some thought, "Since the kindness of the Manchu Emperor has been so great, he will not forget about us even now. Therefore, we should not divorce ourselves from China." Others said, "The Chinese government will collapse before long. Therefore, so long as we have no agreements with the enemies [the British] nearby, we will certainly be conquered. So it would be good if we had close relations with them." Still others said, "The Russians, being very rich and powerful, we would not fall into the enemy hands. Also, since they are far away, they could not devour us. But for just that same reason, it is difficult to work with them."

In St. Petersburg, meanwhile, Norzunov accepted a commission from the Imperial Geographical Society to photograph Tibet with a camera it provided him. He very probably met with the Tsar. A note from Ukhtomsky to Nicholas II asked him to receive two Kalmyks, one being Norzunov. "You know how I love Buriats," remarked the ever-hopeful Prince, "but Kalmyks are closer and more akin to us on account of their martial character and other virtues. We have not yet had the last word on the awakening of Central Asia." In January 1900 Norzunov stopped in Paris, where at Dorzhiev's request, he took delivery of four crates of steel begging bowls that had been ordered to replace an earlier shipment lost when a coracle capsized in a Tibetan river. On his departure from Marseilles on the steamer Dupleix, he took aboard one of the crates; the remaining three were to follow on another ship. He arrived in Calcutta that March with a passport from General Nipi Khoraki, the Governor of Stavropol, and a letter of introduction to the French Consul. Concealing his identity, Norzunov registered at the Continental Hotel as Myanoheid Hopityant, an employee of Stavropol's Post and Telegraph Department.

His troubles began when British customs discovered he was carrying a .45 caliber sporting rifle, and confiscated it. Tipped off by a Russian-speaking Briton that he was about to be arrested, Norzunov panicked. He decamped for Darjeeling by train. In spite of his Chinese disguise, he was spotted and placed under house arrest at Ghoom monastery by the Deputy Police Commissioner for Darjeeling. Police records describe him as about 5 feet 10 inches tall, "broad and well built, head now shaved, Mongolian features, slight moustache twisted down Chinese fashion, medium complexion." His age was given as twenty-six. He at first told his interrogators he was a trader from Peking taking the less arduous route to Lhasa. Later he altered his story: he was a Khalkha Mongolian named Obishak. Under further questioning, he finally admitted he had come from Marseilles by way of Calcutta.

From Ghoom, Norzunov managed to get word of his plight to Dorzhiev, who was then about to depart for Russia. Cool as Macavity, Dorzhiev arrived in May at Ghoom as Abbot Sherab Gyatso's guest, carrying a document certifying that Norzunov was a Buddhist who had already made a pilgrimage to Lhasa. When his document failed to impress the British, Dorzhiev felt he had had no choice but to continue his own travels.

A police escort took Norzunov to Calcutta and placed him under arrest. During his detention, Thomas Cook & Son cleared up the matter of the crates of begging bowls that had been impounded, along with the rest of Norzunov's luggage. They forwarded 590 metal bowls, two phonographs, and a camera to Lhasa. Norzunov was expelled from India aboard the Dupleix to Odessa, "on the ground that it is undesirable that a Mongolian or quasi-Russian adventurer with several aliases should trade with Tibet through British India." In a final interrogation, Norzunov produced a letter of recommendation from Prince Ukhtomsky, on the stationery of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society, describing him as a member "undertaking a journey to Tibet on a pilgrimage and in the interests of commerce and science." Norzunov now acknowledged his travel expenses had been paid for by a rich Chinese Mongolian lama from Urga named "Akchwan Darjilicoff" who had studied in Lhasa before visiting Europe. The same rich lama had ordered the steel bowls in Paris from J. Deniker and Cie. He was merely the courier.

Two months after his expulsion, the indefatigble Norzunov was again on his way to Tibet, which he reached in winter 1901.While in Lhasa, he took the photographs commissioned by the Geographical Society. They were published along with an introduction by the American diplomat William W Rockhill in The Century magazine in 1903.

"DARJILICOFF'S" NAME MEANT NOTHING TO NORZUNOV'S interrogators and it would appear that neither the Abbot of Ghoom nor Das volunteered further reports on the matter. (It was their silence that earned Sherab Gyatso, Ugyen Gyatso, and Sarat Chandra Das their probably unwarranted reputation as double agents.) The real Dorzhiev, having thwarted his would-be captors, made his way by sea to China, where he witnessed the Boxer Rebellion. He recorded his impression of a Boxer massacre at the Chinese city of Aigun on the Amur River: "Those who killed everyone and burned the city down without leaving a trace may have been men, but their brutality was greater than that of tigers and leopards." Finding Peking besieged by Chinese rebels, he proceeded to Japan, then to Vladivostok, and traveled by train and steamer to St. Petersburg, only to learn that his patron, Prince Ukhtomsky, had just been dispatched to Peking. To break the tedium of waiting for a royal audience, Dorzhiev revisited Paris, and ordered more begging- bowls.

Eventually, Dorzhiev, armed with a letter from the Dalai Lam.a, met with Tsar Nicholas on September 30, 1900, at Livadia, the Tsar's palace at the Crimean resort of Yalta. This time the audience was reported in the columns of the Journal de Saint-Petersbourg. Having witnessed the Boxer massacres in China, the lama was now convinced that the intrusion of Europeans and their missionaries in Asia could have catastrophic results. As described by the Russian Foreign Ministry, the purpose of this mission was to seek "the intercession of Russia for Tibet, which is menaced ... by England, mainly from Nepal." There was the ritual exchange of presents, but otherwise the White Tsar proffered little. Dorzhiev made better headway with the Minister of War, General Kuropatkin, who promised the Tibetans the "cannons of the latest make" which the Russians had captured during the Boxer Rebellion. All this Dorzhiev reported on his return to Lhasa, where he presented the Dalai Lama with the Tsar's gifts, a gold watch studded with diamonds, and a "gorgeous set of clerical vestments."

In 1901 Dorzhiev and Norzunov were again on the move, passing through Nepal en route to Petersburg. According to a British intelligence report, Dorzhiev's abrupt departure from Lhasa was prompted by the Chinese Amban, who, angered by his unauthorized diplomatic negotiations, issued a warrant for his arrest. In Katmandu, Dorzhiev visited monasteries and made offerings of powdered gold and saffron at the great Bodh-Nath stupa. In a boastful moment, he showed the chief lam.a the inscribed watch worth 300 rupees given him by the Russians-an episode promptly reported to the British. At the Nepalese border, British guards searched his luggage but failed to find the gifts he was carrying from the Panchen Lama, or the letters from the Dalai Lama intended for the Tsar. Nor did border officials discover Norzunov's Russian passport, which he had hidden in the sole of a boot, or the films tucked in a small box inside his trousers. In Colombo, with the assistance of the Russian consulate, the party of six embarked without incident on the Russian liner Tambov on June 12, 1901, bound for Odessa.

There Dorzhiev and his party were accorded a rousing welcome, complete with roses, blaring music, and crackling fireworks. The Russian press described the group as "Extraordinary Envoys of the Dalai Lama of Tibet. "The British Consul General, in a hastily cabled report, remarked that when the Grand Lama's mission disembarked, "they were met with real Russian cordiality, with bread and salt on a gold-plated tray," all of which "produced a deep and pleasant impression on the Lamas." As much pomp surrounded Dorzhiev's audience with the Tsar at Peterhof. The Dalai Lama's letter, written in Tibetan with a copy in Mongolian, was resoundingly firm: "The Buddhist faith of the Tibetan people is threatened by enemies and oppressors from abroad -- the English. Be so kind as to instruct my ambassadors how they may be reassured about their pernicious and foul activities." The Tibetan pontiff made no specific requests for assistance, but rather expressed a hope for protection. A passage suggesting Dorzhiev's influence asserts: "Your Majesty does not reject people who confess different religions ... and especially expresses solicitude towards the Buddhist Kalmyks and Buriats."

In a careful response, Nicholas was noncommittal. His Majesty expressed pleasure "about your wish to establish regular connections between the Russian State and Tibet" and ventured the hope that "given the friendly and fully well-disposed attitude of Russia, no danger will threaten Tibet in her fortune hereafter."

Besides meeting with the Tsar, Dorzhiev conferred with Finance Minister Witte, War Minister Kuropatkin, and Foreign Minister Lamsdorff. When asked if St. Petersburg might open diplomatic relations with Tibet, Dorzhiev responded that if the Russians allowed a consulate in Lhasa, the British would want representation as well. The Dalai Lama's emissary suggested instead that Russians could open a consulate just across the Chinese-Tibetan border, with Buddha Rabdanov as consul. With its advantageous location and a telegraph connection to Lhasa, the consulate could promptly pass news from Tibet to the Russian Foreign Ministry. Authorized the following year, the consulate was opened at Ganding in Szechuan, in autumn 1903.

As before, Dorzhiev returned to Lhasa laden with gifts and, according to his memoir, "documents written in solid gold letters stating the relations between Russia and Tibet." But this was not a treaty. The Buriat's missions had not achieved Lhasa's overriding objective, a formal alliance in which Russia would agree to protect the Tibetans. In his invaluable recollections, published in 1926, the Russian diplomat Ivan Yakobevich Korostovets provides a sense of the lama's negotiating style: "Dorzhiev spoke with marked authority and expertise, and mightily pleased the Tsar, in spite of his fantastic plans, which were not to be realized and which implied a Russian advance across the Himalayas in order to liberate the oppressed people ... He behaved in a very modest way yet demanded respect, while at the same time he was mysteriously anxious to avoid attracting the attention of the English to his mission."

Aside from specialized academic works, little attention has been paid by biographers to Nicholas II's obsession with the East. Following his Asian Grand Tour in the company of Ukhtomsky, the Tsarevich consented in 1893 to serve as chairman of the Siberian Railway Committee, a major Witte project. Indeed, his support for Witte's ambitious schemes contributed to the ill-starred Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, which in turn contributed to the Finance Minister's downfall. Many of the Tsar's advisers justifiably complained that Russia's limited resources were squandered in Asia. The War Minister, General Kuropatkin, noted with alarm in his diary entry for September 22, 1899: "The Emperor is restless on foreign policy matters. I consider one of the sovereign's more dangerous character traits to be his love for mysterious lands and individuals such as the Buriat Badmaev and Prince Ukhtomsky. They inspire him with fantasies about the Russian Tsar's greatness as ruler over all Asia. The Emperor is drawn to Tibet and similar places. This is all very worrisome, and I shudder about the harm these delusions may cause to Russia."

In March 1903, Kuropatkin communicated his fears to the Finance Minister: "I told Witte that our sovereign has grandiose plans in his head: to absorb Manchuria into Russia, to begin the annexation of Korea. He also dreams of taking Tibet under his orb. He wants to rule Persia, to seize both the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles."

Despite Witte's successes as Finance Minister -- during his ten-year tenure, the revenues of the empire nearly doubled -- he was brought down in 1906 after Russia's military debacle in the East, his demise hastened by the intrigues of his rivals. Witte was demoted to the purely ceremonial post of President of the Committee of Ministers. As his stock declined, so did Ukhtomsky's. Yet if Dorzhiev failed to obtain the wholehearted support for Tibet he sought from the Russians, his missions played to the worst fears of Lord Curzon, the Viceroy of India, who was rarely half-hearted about anything.

_______________

Notes:

i. The Russians carefully cultivated the belief that the Tsar was the ''tsagan'' or "White Khan," the heir to Ghengis Khan. What we know as the Golden Horde was actually called the White Horde by the Russians, thus the appellation "White Tsar."