From Stone to Parchment: Epigraphic and Literary Transmission of Some Greek Epigrams

by Sara Raczko

Trends in Classics, vol. 1, pp. 90-117

© Walter de Gruyter 2009

2009

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Abstract: This paper deals with an oft-neglected aspect of the complex relationships between the Hellenistic culture and the Archaic and Classical tradition, namely the epigrams handed down to us in both epigraphical and literary sources. These (unfortunately rare) epigrams represent the only opportunity we have to detect the divergence between the original Archaic or Classical texts preserved on stone and their copies transmitted by manuscripts. Indeed, the Archaic and Classical epigrams have usually been handed down to us either as inscriptions or in manuscript copies, but very rarely in both forms. During the literary transmission the epigrams were modified in many ways: e.g. the writing conventions of the Archaic alphabets were abandoned and replaced by the "standard" system, and the linguistic shape suffered remarkable alterations. One of the aims of this paper is to explore the nature of the modifications undergone by some Archaic and Classical epigrams on stone during their literary transmission.

Obviously, most of the modifications found in the literary tradition are either banal scribal errors or alterations due to the well-known tendency of those who copied the texts to turn dialect forms into their Attic (Koine) counterparts. Yet in some instances the modifications seem to be deliberate and in line with the typically Hellenistic tendency to "embellish" the texts by means of dialect forms absent from the original but perceived as "prestigious". It is precisely on this tendency and its effects on the texts that I shall dwell in this paper.

Keywords: Epigrams, "embellishment", Doric [a:], dialect mixture

§ 1. In Archaic and Classical times epigrams were inscribed on stone or other durable materials (pottery, bronze); they were anonymous (as a rule, until the 4th cent. B.C.) and were composed on specific occasions, mostly as epitaphs or dedications. During these early stages, the local alphabets and the local dialects played an important role. The epichoric alphabets were used and the linguistic form was the particular dialect of the dedicator himself, 1 even if the monument was set up abroad.2 It is worth noting that dialect inscriptions in prose behave differently from verse inscriptions in this respect: prose inscriptions are exclusively written in the local dialect;3 epigrams, on the other hand, being verse compositions, are influenced by poetical models, above all by epics. In this case too, however, the strength of the local context is evident: epic features or syntagmas appear, as a rule, "translated" into the epichoric dialect or "coloured" with local phonetics, e.g. [x] (Boeotia, CEG 326) and [x] (scil. [x], Corinth, CEG 360), whereas our Homeric text has [x] (scil. [x], Sparta, CEG 373) based on [x] (cf, [x]; 283).4 On the other hand, some epic features - such as gen. sing. [x] and [x], dat. plur. [x], lack of augment, movable -v, etc. - tended to retain their original shape mostly, but not exclusively, for reasons of metrical convenience or necessity. Although this was the normal practice, it was far from being a strict law: verse epigrams show many examples of literary (usually epic) forms used instead of their local counterparts without any metrical necessity, like a participle in [x] in a Thessalian epitaph (CEG 117) metrically equivalent to the local form [x], some cases of psilosis, etc.5 It must be observed, anyway, that the principles governing the use of epic or literary features that were metrically equivalent to the local ones are very difficult to pin down, being neither fixed nor consistent. This is, however, quite obvious, since stone epigrams were no recognised literary genre and were therefore not bound to any well-established standard from this point of view (Buck 1923, 136).

§ 2. During the 5th cent. B.C., a large number of epigrams began to be produced (mainly) in Attica to celebrate private or public events.6 Their style grew more and more refined (according to ancient sources, some were commissioned to famous authors like Simonides, Anacreon, Euripides and Plato)7 and showed an increasing influence of poetry: chiefly epics, elegy and chorallyrics.8 The influence exerted by some literary languages, respectively linked with the Ionic domain and with the Doric one, has been invoked to explain some inconsistencies or "deviations" of the vocalism versus the epichoric features in Archaic and Classical Attic verse epigrams. In particular, it has been argued that the occurrence of [x] after [e], [i], [r] in the place of the expected [a:] (the so-called "alpha purum", a distinctive Attic feature) was due to the influence of epics, while the presence of non-Ionic-Attic inherited [a:] (< IE *a) instead of the expected Ionic-Attic [x] to the prestige of choral lyrics.9

Clearly, in more than one instance the non-Attic vocalism can be explained by the origin of the deceased.10 Nevertheless, there are some cases, like [x] in CEG 272 (470-460? B.C.), for which it is likely that Ionic [x] instead of Attic [a:] [x] was due to deliberate decision to "colour" the epigram with Ionic or epic features.11

Definitely more frequent and more striking is the spelling with non-Ionic- Attic inherited [a:] (< *a) in Attic verse epigrams between the second half of the 6th and the first half of the 5th cent. B.C.: e.g. gen. plur. [x], dat. sing. [x]; [a:] it is also found in [x], or epithets referring to Athena like [x], etc.12 Apart from rare cases in which, again, spellings foreign to Attic are due to the origin of the deceased (CEG 77 and 83, epitaphs for a Spartan and a Megarian), a change in the vocalism for stylistic purposes, and specifically under the influence of choral lyric, may account for most of the occurrences of [a:] (Mess 1898, 12-21; Buck 1923,134-136).13

§ 3. In Hellenistic times the Greek epigram underwent a number of modifications that have been often studied in depth and on which it is impossible to dwell in detail here. Basically, the epigram acquired the status of a literary genre, became more and more detached from the local dialects (which, incidentally, were on the wane), and the tendency to mix up the dialect features increased. For the sake of convenience, Hellenistic epigrams are usually classified by modern scholars into those composed in "Ionic-epic" dialect, in "Doric" dialect and in an "admixture" of the two,14 but it is clear that things were more complicated than that. The coexistence of "Doric" [a:] and "Ionic-epic" [E:] (and the frequent insertion of Doric features in a basically "Ionic-epic" context) is not only attested in literary epigrams, but it is also evident from several Hellenistic epigrams on stone.15

At a surface level there seems to be little more than an increase of a tendency that was already evident in Classical times; but in fact it seems clear that some new "principle" was at work, in the sense that the epigrams shared the same taste for the contamination of Kunstsprachen typical of other Hellenistic literary genres16 and that the use of dialect forms must have been perceived as a means to "embellish" a poetical text; in other words there was some continuity in a remarkably different frame.17

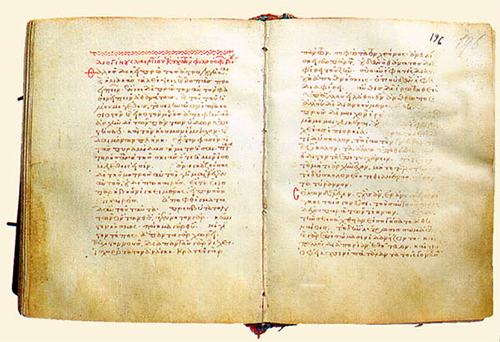

§ 4. As I have said, during the post-Classical period epigrams were not only composed, but also copied from stones and collected in book forms and anthologies.18 The most important one was the Garland of Meleager, which included most of the epigrams transmitted to us, later flown into the Palatine and Planudean Medieval anthologies.19 Therefore, the Hellenistic anthologies contain both pure literary epigrams and poems copied from stones, several of them ascribed to famous poets of the Archaic and Classical age. Although these ascriptions have often been disputed by modern scholars, it is clear and widely accepted that in many cases we are not dealing with book epigrams, but with poems that were composed and actually engraved on monuments during the Archaic and Classical period.20 Usually, these monuments have not been preserved, and we are not able to detect the differences between the original epigraphic text and its literary copy; yet, sometimes this is possible: it is on these occasions that we become aware of how much has been lost with the loss of the epigraphic text.

One of the most serious problems of literary texts is the vagaries of transmission. The linguistic and dialect form is usually the one deepest affected by modifications: apart from mechanical mistakes, the scribes obviously tended to turn the original dialect forms into those of their spoken Koine, which was phonologically Attic. There are plenty of examples: a well-known one is the first hexameter of the famous distichon for the soldiers fallen at Salamis, ascribed to Simonides (FGE "Simonides" XI). The text as we have it in the MSS is [x], but the original on stone (CEG 131) reads: [x], with the expected dialect forms ([x]), turned into their Attic (Koine) counterparts in the literary version.21 More rarely, some modifications are due to the influence of literary texts: the epigram dedicated by the Laconians to Zeus has come down to us both on stone (CEG 367): [x] and in the text of Paus. V, 24, 3: [x]. While the change of [x] into [x] is trivial, the replacement of [x] with [x] was probably due to the fact that [x] is the Homeric form. 22

In this latter case, the replacement due to literary interference is likely to be occasional (an intervention of a learned scribe), but it has a lesson to teach. We are used to explaining the divergences between the original Archaic or Classical epigrams preserved on stone and their literary copy with "unintentional" modifications, like random corruptions, wrong transcriptions on the MSS, alterations into Attic of dialect features, and so on. However, although this is mostly the case, as we have just seen, it is clear that some changes were not mechanical, but made on purpose. In what follows I shall examine some (unfortunately rare) Classical Attic epigrams handed down to us both in the original on stone and in their literary copies in the Palatine Anthology in order to demonstrate that in some cases we are dealing not only with "mechanical" mistakes, but also with intentional modifications. In actual fact, I believe that some epigrams were purposefully tampered with in order to embellish the linguistic (and literary) features of the original epigram according to the tastes of the post-Classical age.

§ 5. Let us examine first AP VI, 138 (= FGE "Anacreon" IX), one of the epigrams of the so-called Sylloge Anacreontea of the Palatine Anthology; more precisely, it is included in the small group of dedicatory epigrams (AP VI, 134-145), ascribed to Anacreon, The set is opened by AP VI, 134, which is headed with [x], while AP VI, 137, that comes right before our epigram, is a dedication of a certain [x] to Apollo. The text of AP VI, 138 in the MS of the Palatine Anthology reads as follows:

[x]

"Formerly Calliteles erected me; but his descendants set this up, to whom give favour in return".

As we have it in our MS, the text falls within the widespread category of the "speaking monuments" ([x]), although the sudden switch from the first person [x] to [x] (scil. the new Herm dedicated by Calliteles' descendants) results, at a first glance, in puzzling syntax, given that at the very beginning of the epigram the statue itself is speaking ([x]), but at the end someone else addresses himself to the god (/statue), asking for thankfulness.24 It must be stressed, however, that this kind of switching is not unparalleled in dedications. As to the destination, it is worth noting that, according to C's lemma "[x]", AP VI, 138 should have been composed in honour of the same god as AP VI, 137, namely Apollo.25

The original on stone of our literary version was found in Attica, in Chaidari (near Daphni). It is written in the local Attic alphabet under a stone Herm dating back to the years 480-460 B.C., although we cannot exclude a slightly later date, namely 470-460 B.C. (IG I [3] 1014; cf. CEG 313); the text is damaged, but perfectly recognisable:

[x]

The discovery of the original monument made us see the epigram under a very different light: to begin with, it is a dedication to Hermes and not to Apollo.26 Moreover, for chronological reasons the ascription of the epigram to Anacreon which had been debated for a long time, turned out to be impossible. Since on epigraphic and palaeographic grounds the inscription is likely to go back to a date between 480 (470?) and 460 B.C.;27 we can safely exclude Anacreon's authorship (he was born in 575 B.C. and supposedly lived 85 years, which takes us to ca. 490 B.C. as the date of his death).

Trypanis 1951 is also convinced that Anacreon cannot be the author of CEG 313 (= AP VI, 138); in his opinion the evidence against Anacreon's authorship rests not on palaeography but on cultural data and he connects the epigram on stone with the spreading of dedications of inscribed marble Herms in Attica. It must be said, however, that Trypanis reconstructs the date of our epigram on stone on feeble bases: firstly, he interprets [x] as 'grandchildren', whereas the term has three possible meanings ('grandchildren', 'descendants' or 'sons',28 each of them would result in a very different chronology as to the generation-gap between the dedication by Calliteles and the second by his [x]; moreover, it is not sure whether or not the Herm dedicated by Calliteles was a marble one.

Trypanis remarks that a marble Herm of square shape with an inscribed epigram is typical of Attica of the 5th cent. B.C. and that the spreading of dedications of marble Herms as cult-statues (from ca. 510 B.C. onwards) came into being in a phase of Hermes' cult in which Hipparchus, the brother of the tyrant Hippias (we are between 528 and 514 B.C.) played an important role. According to some ancient sources, within the framework of the ambitious cultural project of the Peisistratids, Hipparchus summoned to Athens famous poets such as Simonides and Anacreon, and set up marble Herms (the monumental version of the wooden older ones) equipped with epigrams in all of Attica, including country and demes. The [x] served not only as milestones and cult-statues but also as a vehicle for education: some of the epigrams carved on them were allegedly written by Hipparchus himself and his friends.29 Interestingly, during his stay in Athens Anacreon was much admired by the Athenians and later on (during the late-Classical or early-Hellenistic era) he became famous as a composer of epigrams for Herms, probably because of his ties with the Peisistratids.

Through the 5th and 4th cent. B.C., the cult of Hermes became more popular; moreover, the dedication of marble Herms as cult-statues (and not only as milestones) by private citizens more frequent.30 According to Trypanis, our epigram, and probably others of the small Anacreontean Sylloge of the Palatine Anthology, was composed for, and carved on, this kind of Herm.31 Trypanis derives from these bases a hint for discarding the ascription to Anacreon of CEG 313 (= AP VI, 138). According to him, we have the important terminus post quem of 510 B.C. for the dedication of marble Herms with carved epigrams: even if Calliteles was among the first Athenians to set up a marble Herm, since the second one (our Herm) was dedicated by his [x]I = 'grandchildren' we have to calculate three generations, which take us to ca. 480 B.C. As a consequence, even if Anacreon remained in (or returned to) Athens after the death of Hipparchus (514 B.C.), which is indeed possible, and did not leave as frequently assumed,32 he would have already been dead by the time of the dedication of our Herm (see also FGE, 140). As I have said above, Trypanis' conclusions are far from being certain. As Hansen -- who rejects Anacreon's authorship too -- points out, nothing can be inferred from the shape of the second Herm: to begin with, we do not know if the first Herm was one of the marble Herms or a wooden older one; consequently the setting up of inscribed marble Herms by private individuals at the end of the 6th cent. B.C. is no terminus post quem. Moreover, we cannot determine how many years intervened between the setting up of the first and the second Herm, because [x] could in principle stand for [x] and therefore could mean 'sons' or 'descendants' (but see also below). As a consequence, Hansen does not accept the cultural data discussed by Trypanis as evidence: according to him the reasons for discarding Anacreon's authorship rest chiefly on epigraphical grounds.33

In any case, the cultural framework described by Trypanis is important for the literary transmission of AP VI 138: in fact, it is highly likely that because of Anacreon's stay at Athens the ancients began to associate him with verse epigrams on Herms, and this explains why AP VI, 138 was ascribed to him. Besides, it seems that the connection of Anacreon with verse epigrams on Herms was relatively ancient: according to Page (FGE, 123-124) several epigrams, and among them our AP VI, 138, were already ascribed to Anacreon and included in a collection of alleged Anacreontean epigrams which was used by Melager in putting together his Garland.

To sum up, if we did not have the original on stone, we would also lack two important pieces of information: first, the exact nature of the monument, which belongs to a specific phase of the cultural history of Athens; second, the transmission of Calliteles' epigram in the Hellenistic and pre-Hellenistic period, that is to say, the reason for its ascription to Anacreon, possibly dating back to the 4th-3rd cent. B.C., and, in any case, prior to the Garland.

It is time to examine the inscription more closely; as I have said, the text on stone reads:34

[x]

The stone reveals clearly to what extent the literary tradition can modify an original text. Two main points deserve attention:

1) What is carved on the stone is not [x] but [x], with H representing the initial aspirate of [x] (since the epigram was written in the Attic pre-Euclidean alphabet, where H means [h]). As a consequence, the statue was no "speaking monument", and so there is also no syntactical problem due to the fact that the statue apparently starts to speak and then suddenly becomes the object ([x]) of the verb of dedication ([x]) with a different subject ([x]). In all likelihood we are not dealing with any intentional modification of the text, but with a mistake: the pronoun [x] could be put down to a scribe who was used to plenty of cases of "speaking" objects or monuments that he came across in epigrams. Moreover, the mistake is likely to have been facilitated by a text on papyrus in which the old H representing an aspiration was wrongly interpreted as M ([x] > [x]). The difference between [x] of MSS and [x] on the stone is likely to be explained as a consequence of a trivialization too. In Attic inscriptions the two compounds are basically equivalent from the semantic point of view, but [x] is certainly less common than [x]: apart from our example, there are some occurrences of [x] in the 4th and 3rd cent. B.C., then it disappears completely until the 2nd cent. AD.; on the contrary, [x] is consistently attested from its first epigraphical occurrences (second half of the 5th cent. B.C.) onwards.35 A similar scenario is found in literary texts, where [x] is more common and is also frequently attested as varia lectio of [x].

2) On the stone the verb of dedication in the pentameter reads [x], not [x] as in the literary version; as a consequence, the dialect form is not original. What we find on the stone, [x], is the Ionic-Attic form,36 precisely what we expect in an Attic epigram. The middle of [x] with this sense is rare, but well attested already since Homer.37 In other words, if we had only the literary version of Calliteles' epigram, we would accept a dialect feature that was not original.38 Since instances of non-Ionic-Attic ("Doric") inherited [a:] instead of Ionic-Attic [E:] are, although rarely, attested in Attic inscriptional verse epigrams (see above, § 2), we might have been under the misleading impression that the literary version of AP VI, 138 was accurately copied down from an Attic epigram on stone which actually showed an occurrence of [a:] instead of Ionic-Attic [E:] ([x]).

It is obvious that the stone has the original form and that the "Doric" [x] found in the manuscript tradition cannot be due to a banal mistake :39 in my opinion, we are definitely dealing with an intentional manipulation in order to embellish the epigram.

This conclusion is a first important step. The second one is to ascertain according to what principle AP VI, 138 was tampered with. Since the original epigram was copied down and arranged in a collection during the post-Classical age, the easiest and most logical explanation for the alteration of [x] into [x] is that the former was manipulated according to the typically Hellenistic taste for combining elements taken from different literary traditions, i.e. inserting "Doric" [a:] in an Ionic(-Attic) linguistic (and literary) context. In this case we would have a text dating back to the Classical age that was altered or embellished later on according to the linguistic and literary criteria of the Hellenistic (and Roman) period.

In fact, there is another possible explanation, albeit more complex. The Hellenistic age is not only a period of poetical innovation, but also the period par exellence of philological activity on literary texts of the Archaic and Classical age. Since a striking feature of the in Archaic and Classical Attic epigrams on stone was the presence of non-Ionic-Attic ("Doric") [a:] instead of an expected [E:],40 a Hellenistic editor may have felt to be authorised to modify a banal [E:] into [a:]. In other words, sometimes later scholars or editors may have decided to "restore" (to their mind) the original shape of the Attic epigrams copied down from the stone by "characterizing" them by means of the linguistic features they found in the originals on stone and that they regarded as typical of the Archaic and Classical Attic epigrams.41

The latter hypothesis is more daring and, although we have to take it into account, it cannot be proved beyond any doubt; in my opinion the most likely explanation is the first one: an intentional modification based on the linguistic canons of the post-Classical age. Regardless of what principle we assume to have been followed -- either linguistic-literary or philological, we are in any case dealing with a deliberate alteration of a Classical epigram, whose original shape is guaranteed only by the stone.

The hypothesis of a deliberate embellishment is strengthened by the linguistic features of a couplet added at a later stage to a Classical epigram. 42 In the Palatine Anthology we find the following epigram, AP VI, 144 (Beckby) = FGE "Anacreon" XV (also AP VI, 213 his, see below)43:

[x]

"Leocrates, son of Stroebus, when you dedicated this statue to Hermes, the beautiful haired Graces did not fail to notice you, nor the delightful Academy, in whose embrace I declare to whom approaches your beneficence".

The original verse inscription (IG I [3] 983 = CEG 312) was found in Marcopoulo in the Attic Mesogeia and dates back to 460? B.C. (IG I [3] 983); such early dates as 470-460 or even 480-475? (CEG 312) have been proposed, but they seem less likely. Only the first couplet can be read (with some difficulty) on the stone:

[x]

The recovery of the original is important (a) since it is an inscribed marble Herm like that of Calliteles (note that inscribed marble Herms are rare)44; (b) since the epigram was ascribed to Anacreon in antiquity (note that Anacreon was famous as epigrammatist of Herms). Although in the MSS of the Palatine Anthology the epigram is transmitted not only as VI, 144, but also as VI, 213 his among a set of epigrams ascribed to Simonides, in all probability its original position was actually in the Anacreontean set and its placement among the Simonidea is likely to be much later than the Garland of Meleager.45 For chronological reasons the ascription to Anacreon (or Simonides) can be discarded, but in any case the question of the authorship does not affect our main interest, namely the differences between the original on stone and its literary copy.

First of all, the Herm reveals something that several scholars had already suspected, namely that the second distichon is a later addiction (moreover linked to the previous one in an inadequate way). Leocrates' dedication is indeed perfectly concluded in itself and the style of the second distichon suggests that the appendage dates back to the post-Classical age (see also below). There is no possibility that the four-line epigram as we have it in the Palatine Anthology is genuine: Wilamowitz (1913, 145-146 n. 2) put forward the hypothesis (accepted by Friedlander - Hoffieit 1948, 114) that the monument was dedicated by Leocrates in the first instance, inscribed with the initial couplet (the one found in Marcopoulo), and then a second time in the Academy, on which occasion he would have added the second couplet. In actual fact, the most plausible explanation for the startling mention of the Academy in v. 3 (obviously at Athens, whereas the Herm equipped with the original epigram was found in the Attic Mesogeia, far away from Athens), is simply that the author of the second couplet, in choosing a fictitious collocation for the statue, was conditioned by the presence in the original epigram of the [x] and Hermes, deities with whom the Academy was closely connected.46 Moreover, the style of the second couplet contrasts with that of the first, being characterized by a combination of elevated and sophisticated expressions such as [x] (whose semantics reflects a late development) 47 or [x].48 Such stylistic features are lacking in the first couplet.

Obviously enough, the two couplets present different problems. As to the first, the stone gives us the opportunity to reconstruct the original shape of the lines, while the MSS tradition has an error in the case of the name of Leocrates' father49 and the usual writing [x] for [o:], plainly different from what is actually engraved on the monument, i.e. [x] with the value of [o:], a graphic solution derived from some Ionic alphabets, and sporadically attested in other Attic inscriptions.50

The author of the second distichon is not merely pleased with sophisticated terms, but the embellishment involves another level: once more, we find an alteration of the expected vocalism (as in the case of the epigram of Calliteles), both in [x] instead of [x] and in [x] instead of [x]. In an Attic epigram we would expect the Ionic-Attic form [x] with [E:], already found in Homer and Hesiod (cf. AP IX, 189). Instead, we have [x] with [a:], attested in Pindar and in the choral lyrics of tragedy.51

Since the use of [x] had been hallowed by Homer and Hesiod, it was perfectly suitable for the elevated style of an epigram; as a consequence the choice of the "lyric" [x] sounds as a distinct affectation and the presence of the Ionic-epic [x] in the following line is yet another indication that we are before an instance of intentional dialect mixture. This hypothesis is likelier than my second one, namely that a later editor wanted to characterize the epigrams on the basis of the instances of "authentic" co-occurrences of [E:] and [a:] attested in some Attic epigrams of the Classical age.

Another of our few examples is AP XIII, 13 whose original on stone is IG I[3] 885 = CEG 280 and is in (Ionic)-epic dialect. The epigram has been edited in many ways after the discovery of the original on stone,52 but the text as we have it in the manuscript tradition of the Palatine Anthology reads:

[x]

The text on stone (CEG 280 = IG I[3] 885, ca. 440 B.C.?) found on the Akropolis reads:

[x]

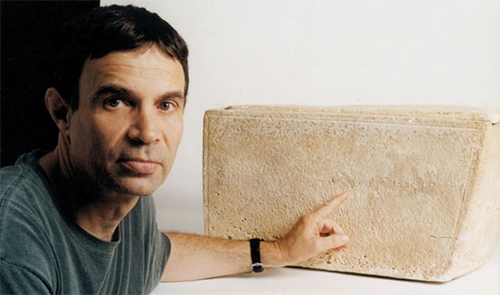

The main differences between the inscription and the literary version are immediately evident: [x] is likely to be a trivialization of the [x] found on the stone (which should possibly be restored) 53, while [x] transmitted by the MSS is very distant from the original text (which scribes were probably not anymore able to understand), [x], which has been recovered from the stone.

So, the stone revealed that the third line is basically the signature of Cresilas from Cydonia (in Crete), a famous artist contemporary with Phidias. The recovering of the original line is a first step; the second one is how to interpret the linguistic shape of the sequence [x]. It is very difficult to draw any satisfactory conclusions, but a possible explanation is that some change in the dialect took place: since the third line is Cresilas' signature, it may have been a switch to his own dialect (very common in artists' signatures), namely to Doric.

Indeed, the artist's personal name, [x], is in his own dialect and although [x] is found in the epics (Hesiod), there are instances of aorists in [x] from presents in [x] in choral lyrics (cf. e.g. [x] in Pindar), so that the artist may have perceived [x] as compatible with Doric but at the same time as a prestigious form of the literary tradition (epics and choral lyrics) and therefore appropriate to the language of the epigram. 54 In this scenario, the ethnic [x] is out of place: we would expect a consistent Doric vocalism [x];55 since there are several instances of adaptation of the ethnics to the dialect of the epigram, we might even expect the form [x], which actually occurs as an ethnic with this shape in Attic texts (cf. Threatte 1980, 135) 56, but not the startling [x].

There is no agreement among scholars on the interpretation of this form. The possible explanations are two: a) some scholars regard [x] as a mechanical mistake, namely a simple graphic inversion of the vowels of the two final syllables;57 b) according to a completely different perspective, [x] would be rather due to the influence of the epics. 58 Of course, the "influence of the epics" is meant in the sense that a Doric form [x] (in the basically Doric context of the third line) was altered by colouring the pre-suffixal vowel with Ionic-epic phonetics. Although the outcome [x] is relatively surprising, it is far from isolated: it is paralleled by some forms with a coexistence of Ion. [E:] and "Dor." [a:], e.g. [x], Eur. Hipp.736 and [x], Bacchil. V, 47; XII, 1 (cf. Buck 1913, 140), and by other examples of substantives in [x] in tragedy (chorals parts) like [x] and [x].59

In the case of other Classical epigrams that have come down to us we are not so lucky, because they are fragmentary and only few letters engraved on the stone are recognisable. In fact, they are clear examples of how these kinds of epigrams can result in a puzzling problem for an editor.60

This is evident in CEG 4 (458 or 457 B.C.? cf. CVI 14), a public monument now lost, commemorating the Athenians fallen at Tanagra. It is literarily transmitted as AP VII, 254 (= FGE "Simonides" XLIX), which reads:

[x]61

The epigraphic text is barely preserved and is reconstructed on the basis of the literary copy, see Hansen's edition (CEG 4):

[x]

Apart from other questions,62 a major problem is that words showing [a:] instead of the expected Ionic-Attic [E:] coexist with words showing the expected long [E:]. A long [a:] is certain for [x] (alpha is in the inscription) and possible for [x] (but Planudes has [x]); it coexists with [E:] in [x] and [x],63 for which we do not have the original on stone and all MSS have a vocalism [E:]. Judging from the examples in the epigrams quoted before, this coexistence is likely to be genuine.64 However, since the epigraphic text is so seriously damaged that in some cases we do not have the original form to compare with, we cannot be sure that the distribution of [a:] and [E:] in the literary version actually reflects that on the stone. For example, in the case of [x] it is only the stone that makes it possible to recover the original with [a:], while the form is transmitted with the Ionic-Attic vocalism (with [E:]) in the MSS of both the Palatine and the Planudean Anthologies.65 On the other hand, in the case of [x] P vs. [x] in Pl all we have is the MS tradition: the likeliest solution is that PI has an Attic trivialized fonn, and that the original is preserved in P, but of course this is far from certain, since P could theoretically have "Doricized" an original [x] or mixed various forms of different traditions. This causes a problem for editors, who make very different choices: as we have just seen, Beckby (and so Hansen in CEG 4) prints [x], alongside [x] and [x], Waltz 1960 prints [x] but [x] (and [x]), while, most surprisingly, Page (FGE "Simonides" XLIX) always prints the "Doric" forms ([x] and [x]).66

AP VI, 343 (Beckby) (= FGE "Simonides" III)67 makes clear once again how difficult it is to detect in full the differences between the epigraphic original and the literary version of the same epigram because of the poor conditions of the text on stone. AP VI, 343 is a copy of an Attic epigram, IG I[3] 501 B (quoted also by Hdt. V, 77; Diod. X, 24, and partly by Aristides XLIX, 65 D.):

[x]

"Having defeated the Boeotians and Chalcidians in the work of the war, the sons of the Athenians quenched their arrogance in sorrowful iron chains and dedicated these horses to Pallas as a tithe of their ransom".

The epigram, although less relevant to the present discussion (since [x], and [x] found in the MSS are corruptions ascribable to the literary transmission, whose most reasonable correction seems [x]; see below n. 69), is worth briefly mentioning because we have the fragments of two different versions on stone, a phenomenon comparatively rare, but not unparalleled. In 507/6 Euboeans and Boeotians invaded Attica while the Athenians were fighting against a Peloponnesian army; nevertheless, the Athenians were able to defeat the Euboeans and Boeotians and to take many prisoners. The tithe of the ransom was used to erect a monument that was then destroyed by the Persians in 480 B.C. Many years later, a replica of the monument was set up on the Acropolis, probably slightly after 457 B.C., to celebrate the Athenian victory over the Boeotians at Oenophyta.68 Fragments of both versions were found in the second half of the 19th century: IG I[3] 501 B (stoichedon, ca. 455 B.C.) has the lines in the same order of all the literary sources (Hdt., AP, etc.); while the other, which was recovered ca. 15 years later (IG I[3] 501 A, ca. 505 B.C.) shows the lines in a different order, namely an inversion of the first and the third hexameter); see CEG 179:

[x]

It is generally held that the latter was the original version and, on the contrary, that the literary tradition, starting with Herodotus, depends from the second version. It is likely that when the replica of the old monument was set up the new victory was linked to the earlier one, and the sequence of the lines was altered because now the focus was on the supremacy gained by the Athenians upon some of their major Greek enemies.

§ 6. And now some remarks by way of conclusion. The Greek epigrams attested both on stone and in manuscript copies are very few but extremely interesting, since they provide us with the unique opportunity of examining the alterations undergone by the texts during the literary transmission. Quite often we find the obvious mistakes we expect: an epigram originally written on a monument dedicated to a certain god appears in, say, the Palatine Anthology as addressed to a different god; a proper name is misspelt; a dialect feature is turned into its Attic-Ionic counterpart because the scribes tended to trivialize forms that sounded unfamiliar to them.

Yet, this is not the whole story. In some cases we are clearly dealing with deliberate alterations of the original, which took place at some point during the transmission, some of them concerning the dialect choices of the originals. Two slightly different explanations of these dialect alterations are possible. Since a certain amount of dialect mixture is already evident in many Archaic epigrams on stone one might argue that, say, [x] was written by an editor (or a learned scribe) instead of [x] because he wanted to convey the flavour of the dialect treatment of epigrams in a bygone era.

It is also possible, and in my opinion far more probable, that the text was altered not according to scholarly principles of learned reconstruction, but in the wake of the typically Hellenistic tendency to mix up dialects in order to "embellish" literary texts. If we had more originals on stone (or metal) we would certainly discover that the dialect of many of our literary epigrams copied from Archaic or Classical monuments was more or less heavily manipulated in Hellenistic and Roman times.70