by Wikipedia

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

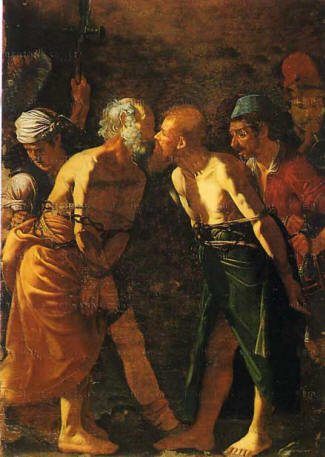

Farewell of Saints Peter and Paul, showing the Apostles giving each other the holy kiss before their martyrdom. (Alonzo Rodriguez, 16th century, Museo Regionale di Messina).

The kiss of peace is a traditional Christian greeting dating to early Christianity.

The practice remains a part of the worship in traditional churches, including the Roman Catholic Church, Eastern Catholic Churches, Eastern Orthodox churches, Oriental Orthodox churches and some liturgical mainline Protestant denominations, where it is often called the kiss of peace or sign of peace, or simply peace or pax.

Sources

It was the widespread custom in the ancient western Mediterranean for men to greet each other with a kiss on the cheek. That was also the custom in ancient Judea and practiced also by Christians. In the Gospels, greeting with a kiss was also the custom practiced by Jesus - e.g. Luke 7:45.

However, the New Testament's reference to a holy kiss (en philemati hagio) and kiss of love (en philemati agapēs) transformed the character of the act beyond a greeting. Such a kiss is mentioned five times in the New Testament:

Romans 16:16 — "Greet one another with a holy kiss" (Greek: ἀσπάσασθε ἀλλήλους ἐν φιλήματι ἁγίῳ).

I Corinthians 16:20 — "Greet one another with a holy kiss" (Greek: ἀσπάσασθε ἀλλήλους ἐν φιλήματι ἁγίῳ).

II Corinthians 13:12 — "Greet one another with a holy kiss" (Greek: ἀσπάσασθε ἀλλήλους ἐν ἁγίῳ φιλήματι).

I Thessalonians 5:26 — "Greet all the brothers with a holy kiss" (Greek: ἀσπάσασθε τοὺς ἀδελφοὺς πάντας ἐν φιλήματι ἁγίῳ).

I Peter 5:14 — "Greet one another with a kiss of love" (Greek: ἀσπάσασθε ἀλλήλους ἐν φιλήματι ἀγάπης).[1]

The writings of the early church fathers speak of the holy kiss, which they call "a sign of peace", which was already part of the Eucharistic liturgy, occurring after the Lord's Prayer in the Roman Rite and the rites directly derived from it. St. Augustine, for example, speaks of it in one of his Easter Sermons:

Then, after the consecration of the Holy Sacrifice of God, because He wished us also to be His sacrifice, a fact which was made clear when the Holy Sacrifice was first instituted, and because that Sacrifice is a sign of what we are, behold, when the Sacrifice is finished, we say the Lord's Prayer which you have received and recited. After this, the 'Peace be with you’ is said, and the Christians embrace one another with the holy kiss. This is a sign of peace; as the lips indicate, let peace be made in your conscience, that is, when your lips draw near to those of your brother, do not let your heart withdraw from his. Hence, these are great and powerful sacraments.[2]

Augustine's Sermon 227 is just one of several early Christian primary sources, both textual and iconographic (i.e., in works of art) providing clear evidence that the "kiss of peace" as practiced in the Christian liturgy was customarily exchanged for the first several centuries, not mouth to cheek, but mouth to mouth (note that men were separated from women during the liturgy) for, as the primary sources also show, this is how early Christians believed Christ and his followers exchanged their own kiss. For example, In his Paschale carmen (ca. 425-50), Latin priest-poet Sedulius condemns Judas and his betrayal of Christ with a kiss thus, "And leading that sacrilegious mob with its menacing swords and spikes, you press your mouth against his, and infuse your poison into his honey?"[3] The kiss of peace was known in Greek from an early date as eiréné (εἰρήνη) ("peace", which became pax in Latin and peace in English).[4] The source of the peace greeting is probably from the common Hebrew greeting shalom; and the greeting "Peace be with you" is similarly a translation of the Hebrew shalom aleichem. In the Gospels, both greetings were used by Jesus - e.g. Luke 24:36; John 20:21, 20:26. The Latin term translated as "sign of peace" is simply pax ("peace"), not signum pacis ("sign of peace") nor osculum pacis ("kiss of peace"). So the invitation by the deacon, or in his absence by the priest, "Let us offer each other the sign of peace", is in Latin: Offerte vobis pacem ("Offer each other peace" or "Offer each other the peace").

From an early date, to guard against any abuse of this form of salutation, women and men were required to sit separately, and the kiss of peace was given only by women to women and by men to men.[4]

Contemporary practices

Presently, the greeting is not normally shared as a kiss in English-speaking cultures, but by shaking hands or performing some other greeting gesture (such as an embrace) more in tune with the culture and time. Handshaking was popularised by Quakers as a sign of equality under God. The passage Galatians 2.9d: "They gave me and Barnabas their right hands of fellowship" (Greek: δεξὰς ἔδωκαν ἐμοὶ καὶ Βαρναβᾷ κοινωνίας) is interpreted by some as a handshake or embracing.

In the Eastern Orthodox Church, in the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom (c. AD 400), the exchange of the peace occurs at the midpoint of the service, when the scripture readings have been completed and the Eucharistic prayers are yet to come. The priest announces, "Let us love one another that with one accord we may confess--" and the people conclude the sentence, "Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, the Trinity, one in essence and undivided." At that point the Kiss of Peace is exchanged by clergy at the altar, and in some churches among the laity as well (the custom is being reintroduced, but is not universal). Immediately after the peace, the deacon cries "The doors! The doors!"; in ancient times, the catechumens and other non-members of the church would depart at this point, and the doors be shut behind them. At that, worshipers then begin reciting the Nicene Creed. In the Eastern Orthodox Liturgy, the Kiss of Peace is preparation for the Creed: "Let us love one another that we may confess...the Trinity."

Not only the sacrifices to the generative deities, but in general all the religious rites of the Greeks, were of the festive kind. To imitate the gods, was, in their opinion, to feast and rejoice, and to cultivate the useful and elegant arts, by which we are made partakers of their felicity. This was the case with almost all the nations of antiquity, except the Egyptians and their reformed imitators the Jews, who being governed by a hierarchy, endeavoured to make it awful and venerable to the people by an appearance of rigour and austerity. The people, however, sometimes broke through this restraint, and indulged themselves in the more pleasing worship of their neighbours, as when they danced and feasted before the golden calf which Aaron erected, and devoted themselves to the worship of obscene idols, generally supposed to be of Priapus, under the reign of Abijam.

The Christian religion, being a reformation of the Jewish, rather increased than diminished the austerity of its original. On particular occasions however it equally abated its rigour, and gave way to festivity and mirth, though always with an air of sanctity and solemnity. Such were originally the feasts of the Eucharist, which, as the word expresses, were meetings of joy and gratulation; though, as divines tell us, all of the spiritual kind: but the particular manner in which St. Augustine commands the ladies who attended them to wear clean linen, seems to infer, that personal as well as spiritual matters were thought worthy of attention. To those who administer the sacrament in the modern way, it may appear of little consequence whether the women received it in clean linen or not; but to the good bishop, who was to administer the holy kiss, it certainly was of some importance. The holy kiss was not only applied as a part of the ceremonial of the Eucharist, but also of prayer, at the conclusion of which they welcomed each other with this natural sign of love and benevolence. It was upon these occasions that they worked themselves up to those fits of rapture and enthusiasm, which made them eagerly rush upon destruction in the fury of their zeal to obtain the crown of martyrdom. Enthusiasm on one subject naturally produces enthusiasm on another; for the human passions, like the strings of an instrument, vibrate to the motions of each other: hence paroxysms of love and devotion have oftentimes so exactly accorded, as not to have been distinguished by the very persons whom they agitated. This was too often the case in these meetings of the primitive Christians. The feasts of gratulation and love, the αγαπαι and nocturnal vigils, gave too flattering opportunities to the passions and appetites of men, to continue long, what we are told they were at first, pure exercises of devotion. The spiritual raptures and divine ecstasies encouraged on these occasions, were often ecstasies of a very different kind, concealed under the garb of devotion; whence the greatest irregularities ensued; and it became necessary for the reputation of the church, that they should be suppressed, as they afterwards were by the decrees of several councils.

-- A Discourse on the Worship of Priapus: And Its Connection with the Mystic Theology of the Ancients, by Richard Payne Knight

In the early centuries the kiss of peace was exchanged between the clergy: clergy kissing the bishop, lay men kissing laymen, and women kissing the women, according to the Apostolic Constitutions. Today the kiss of love is exchanged between concelebrating priests. Such has been the case for centuries. In a few Orthodox dioceses in the world in the last few decades, the kiss of peace between laymen has attempted to be reinstituted, usually as a handshake, hugging or cheek kissing.

Another example of an exchange of the peace is when, during the Divine Liturgy, the Priest declares to the people "Peace be with you", and their reply: "And with your Spirit". More examples of this practice may be found within Eastern Orthodoxy, but these are the most prominent examples.

In the Tridentine Mass, the 1962 version of which is now an extraordinary form of the Roman Rite, the sign of peace is exchanged only among the sacred ministers and clergy. The sign of peace is given by the celebrant to the deacon, who in turn gives it to the subdeacon, who gives the sign to any other clergy present in choir dress. In this context, the sign of peace is given by extending both arms in a slight embrace with the words "Pax tecum' (Peace be with you).

In the Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite of the Mass the sign of peace, if used, is exchanged shortly before Holy Communion, following the Lord's Prayer and the Agnus Dei. The instruction Redemptionis Sacramentum of 25 March 2004 explains: "According to the tradition of the Roman Rite, this practice does not have the connotation either of reconciliation or of a remission of sins, but instead signifies peace, communion and charity before the reception of the Most Holy Eucharist."[5]

The manner prescribed is as follows: "It is appropriate that each one give the sign of peace only to those who are nearest and in a sober manner. The Priest may give the sign of peace to the ministers but always remains within the sanctuary, so as not to disturb the celebration. He does likewise if for a just reason he wishes to extend the sign of peace to some few of the faithful."[6]

In the Roman Catholic rite of the Holy Mass, as well as in the Lutheran Divine Service, immediately after the Doxology, the congregation will partake in the Pax or Rite of Peace. In most Western churches, this involves a handshake and the words "Peace be with you." When the people know each other, a hug may be substituted. Spouses tend to hug and/or kiss each other first before using the traditional handshake and "Peace be with you" for the other surrounding members of the congregation. In lieu of a handshake, a bow to each other is also used as the sign of peace, such as in China, where bowing follows cultural tradition. The bow is sometimes used in the West as a measure to avoid contagions during flu or cold season.

Different Protestant and Reformed churches have readopted the holy kiss either metaphorically (in that members extend a pure, warm welcome that is referred to as a holy kiss) or literally (in that members kiss one another). This practice is particularly important among many Anabaptist sects.

References

1. It has been noted that these mentions of the holy kiss come at the end of these epistles. Since these epistles were addressed to Christian communities they would most probably have been read in the context of their communal worship. If the assemblies for worship already concluded in a celebration of the Eucharist the holy kiss would already have occurred in the position it would later occupy in most ancient Christian liturgical tradition (with the exception of the Roman Rite), namely after the proclamation of the Word and at the beginning of the celebration of the Eucharist.

2. SERMON 227, The Fathers of the Church,(1959), Roy Joseph Deferrari, Genera editor, Sermons on the Liturgical Seasons, vol. 38, p. 197. [1] See also: Sermon 227 in The Works of Saint Augustine: A New Translation for the 21st Century, (1993), Vol. 6, part, 3, p. 255. ISBN 1-56548-050-3

3. For a documented discussion of the mouth-to-mouth early Christian kiss of peace, see Franco Mormando, "Just as your lips approach the lips of yours brothers: Judas Iscariot and the Kiss of Betrayal," in Saints and Sinners: Caravaggio and the Baroque Image, ed. F. Mormando (Chestnut Hill, MA: McMullen Museum of Boston College, 1999), pp.179-190.

4. Catholic Encyclopedia - Kiss

5. Redemptionis Sacramentum, 71

6. Redemptionis Sacramentum, 72