Re: Robert Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell, by Wikipedi

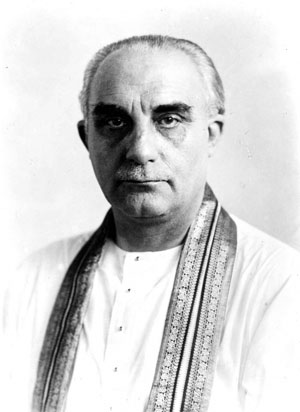

George S. Arundale

by Theosophy Wiki

Accessed: 5/19/18

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

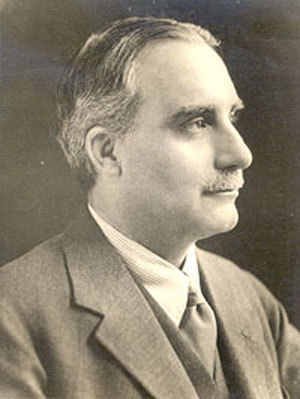

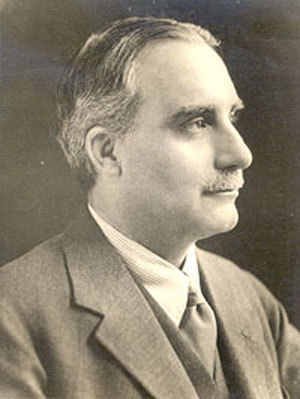

George S. Arundale

George Sydney Arundale (1878–1945) was an English Theosophist, educator, writer, and editor. He served as the third President of The Theosophical Society based in Adyar, India from 1934 to 1945.

Early years and education

George Sydney Arundale was born on December 1, 1878 in Surrey, England, the youngest child of the Reverend John Kay, a Congregational minister.[1] His mother died at childbirth, and George was adopted by his aunt, Francesca Arundale. Miss Arundale joined the Theosophical Society in 1881 and often welcomed Madame H. P. Blavatsky to her home[/b] at 77 Elgin Crescent, Notting Hill, London. George became a member in 1895 and joined the London Lodge. A. J. Hamerster recounted the affection that both HPB and Colonel Olcott had for the boy:

Young George was tutored for some time by C. W. Leadbeater, along with Dennie Sinnett and C. Jinarājadāsa, then attended schools in Germany, in Italy, and in England. In 1900 he was graduated from St John’s College, Cambridge.

Early education work for the Theosophical Society

When he was seventeen, George was admitted to the London Lodge by A. P. Sinnett. Two years later, at Dr Besant’s invitation, he went to India with his aunt to become Professor of History and English at the Central Hindu College, Benares (now Varanasi). In 1907 he was appointed Headmaster of the Central Hindu College School, and later Principal of the College. He was very popular with both teachers and students, for he had a great understanding of youth.[3] Clara Codd recalled that as Arundale walked around, he would have "Indian boys hanging on each arm. He was very fond of his scholars and they were very fond of him."[4] "After leaving the Central Hindu College, George Arundale at first accompanied Mr. J. Krishnamurti and his brother Nityananda to Europe to help them in their education. Being found unfit for active service in the War, he returned in 1916, at Mrs. Besant's request, to India, and became associated with her and other national leaders in the Home Rule for India campaign."[5]

Arundale was appointed as Principal for the former National University in Madras [now Chennai], where the Doctor of Letters honoris causadegree was confirmed upon him. The diploma was signed by Rabindranath Tagore.[6]

In 1918, he became Registrar for the Society for the Promotion of National Education, which provided support to Indian universities, colleges, and schools. As Registrar, he managed the membership rolls and collected subscription fees.[7]

Marriage

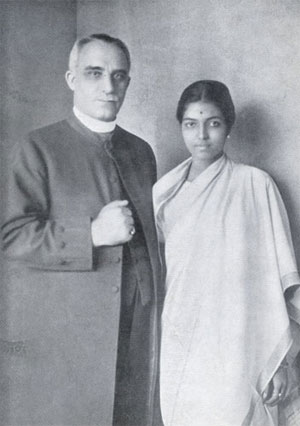

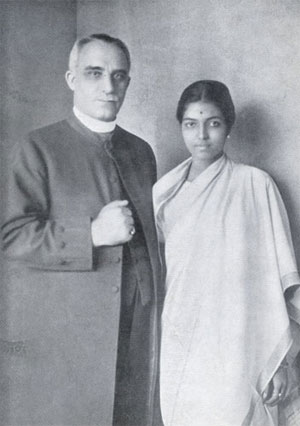

George and Rukmini Arundale

In 1920 Mr. Arundale married Srimati Rukmini Devi, the sixth child a very well-known Theosophical Brahmin family. The ceremony was conducted by Alladi Mahadeva Shastri.[8] Rukmini Devi "was the first well-known Brahmin lady to break caste by marring a foreigner."[9] She and her family were ostracized by their Brahmin associates, but with support of Theosophists, the Indian public eventually adjusted to the marriage. She accompanied him on his worldwide lecture tours, and became well known to Theosophists in many countries.

Rukmini Devi gave an account of travel to England:

Theosophical work

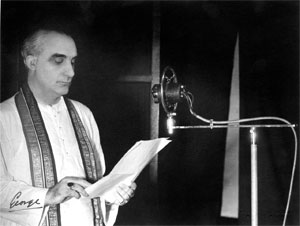

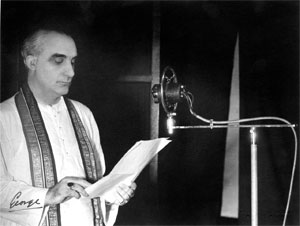

Dr. Arundale reading

Beginning in 1910, Arundale frequently addressed Theosophical Conventions. After a brief period as General Secretary of the Theosophical Society in England, 1915–16, he returned to India to assist Annie Besant in her political activities.

In 1927 he undertook a lengthy lecture tour in Europe and the United States; Mrs Arundale and he were the guests of honor at the American Convention that year, and participated in the dedication of the headquarters building that was then being completed. Each year from 1931 to 1934, he undertook such lecture tours, greatly vitalizing the Theosophical work in the countries he visited."[11]

Social activism and imprisonment

Arundale became the Organizing Secretary of the All-India Home Rule League. He was interned, under house arrest, with Annie Besant and B. P. Wadia, for three months in 1917, under the Defence of India Act, 1917. His official biography states, "From 1924 to 1926 he was President of the Madras Labour Union, which he had been instrumental in forming, and through which he successfully secured a higher minimum wage and less working hours for the working man."[12]

General Secretary in Australia

Dr. Arundale speaking to radio audience.

He became General Secretary in Australia, 1926, where, in addition to his Theosophical duties, he engaged in humanitarian and political work. Bryon Casselberry served as Assistant General Secretary.[13]

Arundale helped to set up the 2GB Broadcasting Station and became its first Chairman of Directors. He lived at The Manor and assisted Bishop Leadbeater in preparing that Theosophical center for its important future. The section journal Theosophy in Australia was renamed to Advance Australia and reshaped as "a monthly magazine of Australian Citizenship and Ideals in Religion, Education, Literature, Science, Art, Music, Social Life, Politics. No. 1 began with July [1926]. There are editorials on the Indian crisis, religious tolerance, food reform, child welfare..."[14]

General Secretary in India

In 1928, Dr. Arundale became General Secretary in India, but he did not seek re-election.

President of the Theosophical Society

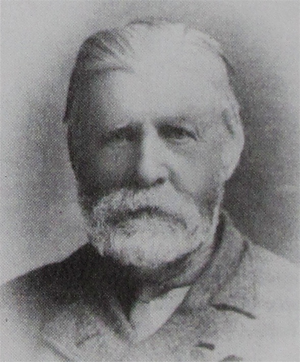

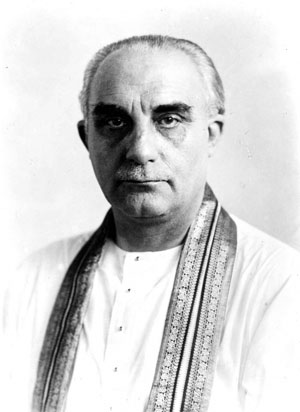

George Arundale

In this account of the Arundale presidency,

In addition to these activities, Dr. Arundale introduced two new serial publications. The International Theosophical Year Book was issued annually from 1937-1942. Wartime stresses on the Society and its staff prevented continuation of this useful publication. The Theosophical World, which changed title to The Theosophical Worker in 1939, was a monthly member newsletter published from 1936-1946.

Co-Masonry

Mr. Arundale became a Co-Freemason in 1902, joining the Order Le Droit Humain. In 1935 he became the Most Puissant Grand Commander, Eastern Federation, and Representative of the Supreme Council.

Liberal Catholic Church

In 1926, he became Regionary Bishop of the Liberal Catholic Church in India.

Unknown Boy Scout with George and Rukmini Arundale

Boy Scout movement in India

"Dr Arundale was known not only for his Theosophical work but also for his interest in ... the Indian Scout movement, being for some years Provincial Commissioner for Madras Province."[16] "In the Central Hindu College he was the captain of the College Cadet Corps, and later became the Deputy Chief Scout of the Indian Boy Scout Movement, which in 1917 amalgamated with Lord Baden Powell's movement at the latter's special request. In appreciation of Dr. Arundale's great services to Scouting, Lord Baden Powell presented to him him own Scout badge."[17]

Later years

Dr. Arundale's official biographical notes on the Theosophical Society, Adyar Web page describe his last months:

Rukmini wrote of his decline:

Mrs. Arundale traveled to Haridwar and Rishikesh to immerse his ashes.[20]

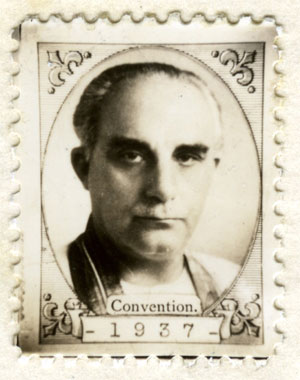

Stamp from Maryland Lodge, 1937.

Honors, awards, and memorials

In 1935, Dr. Arundale was presented with the Subba Row Medal for his contributions to Theosophical literature.

The Shri Bharat Dharma Mahamandal of Benares [a university] conferred upon Dr. Arundale in 1942 the national honor of Vidya-Kalanidhi, which means "storehouse of art and wisdom.” The diploma was signed by His Highness the Maharajadhiraj of Darbhanga, the General President of the university.[21]

In 1937, the Maryland Lodge of the Theosophical Society in America produced stamps with the image of Dr. Arundale for use by American members.[22]

In 1932, an American lodge was established in Santa Barbara, California as the "Arundale Group."

Writings

Dr. Arundale wrote over 2200 articles for Theosophical periodicals, being especially prolific during the years that he served as President and as editor of The Theosophist. The Union Index of Theosophical Periodicals lists articles under George S Arundale, GS Arundale, and GSA.

These are books and pamphlets that he wrote, in chronological order.

• The Growth of National Consciousness in the Light of Theosophy. Madras: Theosophist Office, 1911. "Four lectures delivered at the Thirty-fifth annual convention of the Theosophical Society, held at Adyar, on December 27th, 28th, 29th and 30th, 1910."

• Brotherhood: a Series of Addresses. Benares, India: Rai Iqbal Narain Gurtu, 1913.

• Indian Students and Politics. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House, 1914. Adyar pamphlets; no. 44. Available at Canadian Theosophical Association.

• Thoughts on "At the Feet of the Master". Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1918. Second edition 1919. Available at Hathitrust.

• The Way of Service. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1913. Available at AnandGholap.net. Translated into German, French, and Tamil.

• Man's Waking Consciousness. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1920.

• The Real and the Unreal: being the four convention lectures delivered at Adyar at the forty-seventh anniversary of the Theosophical Society, December, 1922. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1923. Lectures by Annie Besant, C. Jinarajadasa, and George Arundale.

• Bedrock of Education. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1924.

• Thoughts of the Great, to Remind Us "We Can Make Our Lives Sublime"; gathered from time to time for personal guidance. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1924.

• The Ashrama Ideal. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1924. The Brahmavidya Library. no. The opening lecture of the second session of the Brahmavidyãshrama, Adyar, October 2, 1923.

• Understanding Godlike: Poem. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1925.

• Nirvana: a Study in Synthetic Consciousness. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1926. Wheaton: Theosophical Publishing House, 1978. Translated in to French, Spanish, German.

• "The Lord is Here". Adyar, Madras,India: Kalakshetra, 1927. Pamphlet.

• America: Her Power and Purpose. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1928. Booklet.

• The Life Magnificent. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1928.

• The Glory of Sex. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1928. Booklet.

• Some Intolerable Tyrannies. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1928. Booklet.

• Shadows and Mountains. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1928. Pamphlet.

• Go Your Own Way. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1928.

• Mount Everest: Its Spiritual Attainment. Adyar, Madras; London: Theosophical Publishing House, 1933, 1978. Translated into German, Russian, Dutch, Polish.

• My Work as President of the Theosophical Society: A Seven Year Plan; the Spirit of Youth. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1934. Translated into Dutch, Gujarati.

• Freedom and Friendship: the Call of Theosophy and the Theosophical Society. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1935.

• You. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House, 1935. Slightly revised - Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1973. Translated into French, German.

• The Science of Theosophy. London: The Theosophical Society in England, 1935.

• Theosophy as Beauty. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House, 1936. Adyar pamphlets ; no. 208. Available at Canadian Theosophical Association.

• Gods in the Becoming: A Study in Vital Education. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1936.

• Education for Happiness. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1938.

• The Warrior Theosophist. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1938.

• Kundalini: An Occult Experience. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1938. Wheaton: Theosophical Publishing House, 1974. Translated into Spanish.

• Peace and War in the Light of Theosophy: Quotations from Writings and Addresses of George S. Arundale. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1938.

• A Character for Indian Youth. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1939.

• The Lotus Fire: A Study in Symbolic Yoga. Adyar, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1939. Wheaton: Theosophical Publishing House, 1976.

• A Guardian Wall of Will: a Form of Tapas-Yoga. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1939. Pamphlet. Available on Anand Gholap Web page.

• A Fragment of Autobiography. Adyar, Madras,India: Kalakshetra, 1940.

• The Night Bell: Cases from the Case-book of an Invisible Helper. Adyar, Madras, India: Vasanta Press, 1940. Enlarged second edition, 1941.

• From Visible to Invisible Helping. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1941.

• Adventures in Theosophy. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1941.

• Conversations with Dr. Besant, September 20th-October 1st, 1933, on the high seas between Los Angeles & Suva. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1941. Pamphlet.

• Essentials of an Indian Education. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1942. Written with Annie Besant.

• Under the Weather. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House, 1943.

• Inaugural Addresses of Four Presidents of the Theosophical Society. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1946. Lectures by H. S. Olcott, Annie Besant, George S. Arundale, C. Jinarajadasa.

A commemorative book about Dr. Arundale was compiled by friends after his death:

• Personal memories of G.S. Arundale, third President of the Theosophical Society, by some of his numerous friends and admirers. London, Wheaton, IL [etc.] Theosophical Publishing House, 1967.

Notes

1. A. J. Hamerster, "Our New President," The American Theosophist 22.8 (August, 1934), 179-182.

2. A. J. Hamerster, "Our New President," The American Theosophist 22.8 (August, 1934), 179-182.

3. "George Sydney Arundale (1878 - 1945)," Theosophical Society, Adyar Web page. [1]

4. Clara Codd, So Rich a Life (Pretoria: Institute for Theosophical Publicity, 1956), 172.

5. A. J. Hamerster, "Our New President," The American Theosophist 22.8 (August, 1934), 179-182.

6. A. J. Hamerster, "Our New President," The American Theosophist 22.8 (August, 1934), 179-182.

7. Report of the Society for the Promotion of National Education for the Year 1918, (Adyar, Madras, India: Society for the Promotion of National Education, 1918). Kunz Family Collection, Records Series 25.01, Theosophical Society in America Archives.

8. ”Sarada Hoffman,” KutcheriBuzz Website http://www.kutcheribuzz.com/features/in ... sarada.asp, accessed February 28, 2012.

9. Joseph E. Ross, Spirit of Womanhood, privately published by the author, 2009: vii.

10. Rukmini Devi Arundale, "Rukmini on Herself," Rukmini Devi Arundale: Birth Centenary Commemorative Volume, Shakuntala Ramani, ed., (Chennai, India: The Kalakshetra Foundation, 2003), 26.

11. "George Sydney Arundale (1878 - 1945)," Theosophical Society, Adyar Web page. Available at Adyar Web page.

12. "George Sydney Arundale (1878 - 1945)," Theosophical Society Web page. Accessed Adyar Web page on November 4, 2013.

13. "News Items" The Messenger" 14.4 (August 1926), 65.

14. "In Australia" The Messenger" 14.4 (September 1926), 77.

15. "George Sydney Arundale (1878 - 1945)," Theosophical Society Web page. Accessed Adyar Web page on November 4, 2013.

16. "George Sydney Arundale (1878 - 1945)," Theosophical Society, Adyar Web page. [2]

17. "Olcott Scout Benefit Performance," The American Theosophist 22.8 (August, 1934), 188.

18. "George Sydney Arundale (1878 - 1945)," Theosophical Society, Adyar Web page. [3]

19. Rukmini Devi Arundale, "Rukmini on Herself," Rukmini Devi Arundale: Birth Centenary Commemorative Volume, Shakuntala Ramani, ed., (Chennai, India: The Kalakshetra Foundation, 2003), 64.

20. Ibid., 64

21. "Honor for the President," The American Theosophist 30.6 (June 1942), 142. Reprinted from The Theosophical Worker, February, 1942.

22. Stamp produced in 1937 by Maryland Lodge. Scanned from correspondence of George De Hoff to Sidney A. Cook. October 11, 1936. Records Series 08.05. Sidney A. Cook Papers. Theosophical Society in America Archives.

Additional resources

• The Theosophist, Vol. 66, No. 12, September 1945 (Commemorative Issue).

American Section, study course on Theosophy and Theosophical Society (Theosophical Society Archives).

• Dixon, Joy, Divine Feminine: Theosophy and Feminism in England (London: John Hopkins, 2001)

• Lutyens, Mary, Krishnamurti: The Years of Awakening (London: John Murray, 1975)

• Lutyens, Mary, The Life and Death of Krishnamurti (London: John Murray, 1990)

• Meduri, Avanthi (ed.), Rukmini Devi Arundale (1904-1968): A Visionary Architect of Indian culture and the Performing Arts (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 2005)

• Ransom, Josephine. The Seventy-Fifth Anniversary Book of the Theosophical Society. Theosophical Publishing House, 2005.

by Theosophy Wiki

Accessed: 5/19/18

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

George S. Arundale

George Sydney Arundale (1878–1945) was an English Theosophist, educator, writer, and editor. He served as the third President of The Theosophical Society based in Adyar, India from 1934 to 1945.

Early years and education

George Sydney Arundale was born on December 1, 1878 in Surrey, England, the youngest child of the Reverend John Kay, a Congregational minister.[1] His mother died at childbirth, and George was adopted by his aunt, Francesca Arundale. Miss Arundale joined the Theosophical Society in 1881 and often welcomed Madame H. P. Blavatsky to her home[/b] at 77 Elgin Crescent, Notting Hill, London. George became a member in 1895 and joined the London Lodge. A. J. Hamerster recounted the affection that both HPB and Colonel Olcott had for the boy:

The Colonel, in his correspondence with George's adopted mother, refers to him as "the curly-headed angel of Elgin Crescent"; and I remember George himself recently, in one of the Friday evening "roof" talks here [Adyar], telling us of a visit to the Zoological Gardens in London, with H.P.B., who was then much of an invalid, sitting in a bath-chair, and how when he tripped and fell, H.P.B., though only able to move with great difficulty, almost hurled herself out of the chair to pick him up and console him.[2]

Young George was tutored for some time by C. W. Leadbeater, along with Dennie Sinnett and C. Jinarājadāsa, then attended schools in Germany, in Italy, and in England. In 1900 he was graduated from St John’s College, Cambridge.

Early education work for the Theosophical Society

When he was seventeen, George was admitted to the London Lodge by A. P. Sinnett. Two years later, at Dr Besant’s invitation, he went to India with his aunt to become Professor of History and English at the Central Hindu College, Benares (now Varanasi). In 1907 he was appointed Headmaster of the Central Hindu College School, and later Principal of the College. He was very popular with both teachers and students, for he had a great understanding of youth.[3] Clara Codd recalled that as Arundale walked around, he would have "Indian boys hanging on each arm. He was very fond of his scholars and they were very fond of him."[4] "After leaving the Central Hindu College, George Arundale at first accompanied Mr. J. Krishnamurti and his brother Nityananda to Europe to help them in their education. Being found unfit for active service in the War, he returned in 1916, at Mrs. Besant's request, to India, and became associated with her and other national leaders in the Home Rule for India campaign."[5]

Arundale was appointed as Principal for the former National University in Madras [now Chennai], where the Doctor of Letters honoris causadegree was confirmed upon him. The diploma was signed by Rabindranath Tagore.[6]

In 1918, he became Registrar for the Society for the Promotion of National Education, which provided support to Indian universities, colleges, and schools. As Registrar, he managed the membership rolls and collected subscription fees.[7]

Marriage

George and Rukmini Arundale

In 1920 Mr. Arundale married Srimati Rukmini Devi, the sixth child a very well-known Theosophical Brahmin family. The ceremony was conducted by Alladi Mahadeva Shastri.[8] Rukmini Devi "was the first well-known Brahmin lady to break caste by marring a foreigner."[9] She and her family were ostracized by their Brahmin associates, but with support of Theosophists, the Indian public eventually adjusted to the marriage. She accompanied him on his worldwide lecture tours, and became well known to Theosophists in many countries.

Rukmini Devi gave an account of travel to England:

Dr. Arundale had a wide circle of friends in London. His father was a famous architect. I was told that he was invited by the Shah of Oman to renovate his Palace, since at that time, he was considered the best person to do it. The family was well known and they had many friends among the aristocracy and famous artists. Dr. Arundale himself was very popular. We stayed in the house of the Countess De la Warr and there were always people coming and going, garden parties, outings and shipping trips... Mr. Arundale took me to so many concerts and dances, we visited all the museums and art galleries and even among his friends, there were many great artists and painters. He used to play the piano very well, he could also compose music. He wanted me to see everything that the loved and appreciated in Western art.[10]

Theosophical work

Dr. Arundale reading

Beginning in 1910, Arundale frequently addressed Theosophical Conventions. After a brief period as General Secretary of the Theosophical Society in England, 1915–16, he returned to India to assist Annie Besant in her political activities.

In 1927 he undertook a lengthy lecture tour in Europe and the United States; Mrs Arundale and he were the guests of honor at the American Convention that year, and participated in the dedication of the headquarters building that was then being completed. Each year from 1931 to 1934, he undertook such lecture tours, greatly vitalizing the Theosophical work in the countries he visited."[11]

Social activism and imprisonment

Arundale became the Organizing Secretary of the All-India Home Rule League. He was interned, under house arrest, with Annie Besant and B. P. Wadia, for three months in 1917, under the Defence of India Act, 1917. His official biography states, "From 1924 to 1926 he was President of the Madras Labour Union, which he had been instrumental in forming, and through which he successfully secured a higher minimum wage and less working hours for the working man."[12]

General Secretary in Australia

Dr. Arundale speaking to radio audience.

He became General Secretary in Australia, 1926, where, in addition to his Theosophical duties, he engaged in humanitarian and political work. Bryon Casselberry served as Assistant General Secretary.[13]

Arundale helped to set up the 2GB Broadcasting Station and became its first Chairman of Directors. He lived at The Manor and assisted Bishop Leadbeater in preparing that Theosophical center for its important future. The section journal Theosophy in Australia was renamed to Advance Australia and reshaped as "a monthly magazine of Australian Citizenship and Ideals in Religion, Education, Literature, Science, Art, Music, Social Life, Politics. No. 1 began with July [1926]. There are editorials on the Indian crisis, religious tolerance, food reform, child welfare..."[14]

General Secretary in India

In 1928, Dr. Arundale became General Secretary in India, but he did not seek re-election.

President of the Theosophical Society

George Arundale

In this account of the Arundale presidency,

When Dr Besant died in 1933, Dr Arundale was elected President of The Theosophical Society and began from 1934 to work out a Seven Year Plan which included the development of Adyar, and ensuring the solidarity of the Society. With well-prepared publicity material next year he launched a ‘Straight Theosophy’ Campaign, that encouraged the study of basic Theosophical principles, and culminated in the fine Diamond Jubilee Convention at Adyar in 1935. Lodges were urged never to forget their primary purpose of instructing members in Theosophy, using a language that could be understood. The next campaign was entitled ‘There is a Plan’. In 1935 three books of Dr Arundale in which he set forth his conceptions of human and spiritual values, were published: You; Freedom and Friendship and Gods in the Becoming. In 1936 he presided over the Fourth Theosophical World Congress at Geneva, when he decided the third Campaign should be for ‘Understanding’ which, proving successful, was extended into 1938. After that, ‘Theosophy is the Next Step’ was the theme, but the Second World War broke out and not much could be done. He then issued ‘Letters’ to Sections which were widely used and helpful. By 1936 there was a visible improvement in the membership of a number of National Societies, indicating that the President’s vigorous policy was taking effect. The Campaigns were creating new interest and activity. In 1937 Arundale gave a lecture on Symbolic Yoga at the Convention, using his material for ‘roof-talks’ at Adyar, and for his addresses later when on tour in Europe and America. These appeared as a book called The Lotus Fire: a Study in Symbolic Yoga.

However, due to war conditions, travel outside India was not easy. The competent and devoted workers in every Section carried the Society forward under his direction. But all over Europe Lodge after Lodge and Section after Section was forced to close. Increasingly, Dr Arundale devoted himself to the inner side of the work in an endeavour to assuage the suffering of mankind. In an attempt to awaken people to a greater sense of responsibility, he started a small weekly paper in Madras called Conscience. He welcomed to Adyar Dr Maria Montessori and her son, Mario Montessori, who came to India but were unable to return to Italy because of the war. During their stay in Adyar, they trained teachers from India and neighbouring countries in the well-known Montessori method of child education.

In 1940 Dr Arundale set up a Peace and Reconstruction Department so as to have a Charter for World Peace ready when the war ceased. Each year he stressed that members should spread ‘the mighty Truths of Theosophy’, undertook tours in India, and supported the art and educational institutions and activities of Rukmini Devi. He worked hard to build a better understanding on the part of Indians of the position of Great Britain in the West, and for a still more liberal attitude on the part of Great Britain towards India. In 1941 Dr Arundale was conferred the honorary degree of Vidyâ-Kalânidhi, meaning ‘Storehouse of Art and Wisdom’, by the old and much respected institution Shri Bharat Dharma Mahamandal, Benares (now Vârânasi), for his ‘extraordinary merits and excellent qualities’. Dr Arundale’s two special themes were: the unity of India and the development of greatness in the individual.[15]

In addition to these activities, Dr. Arundale introduced two new serial publications. The International Theosophical Year Book was issued annually from 1937-1942. Wartime stresses on the Society and its staff prevented continuation of this useful publication. The Theosophical World, which changed title to The Theosophical Worker in 1939, was a monthly member newsletter published from 1936-1946.

Co-Masonry

Mr. Arundale became a Co-Freemason in 1902, joining the Order Le Droit Humain. In 1935 he became the Most Puissant Grand Commander, Eastern Federation, and Representative of the Supreme Council.

Liberal Catholic Church

In 1926, he became Regionary Bishop of the Liberal Catholic Church in India.

Unknown Boy Scout with George and Rukmini Arundale

Boy Scout movement in India

"Dr Arundale was known not only for his Theosophical work but also for his interest in ... the Indian Scout movement, being for some years Provincial Commissioner for Madras Province."[16] "In the Central Hindu College he was the captain of the College Cadet Corps, and later became the Deputy Chief Scout of the Indian Boy Scout Movement, which in 1917 amalgamated with Lord Baden Powell's movement at the latter's special request. In appreciation of Dr. Arundale's great services to Scouting, Lord Baden Powell presented to him him own Scout badge."[17]

Later years

Dr. Arundale's official biographical notes on the Theosophical Society, Adyar Web page describe his last months:

"In 1945 he was advised complete rest for he was gravely ill, and despite all the care and attention given to him, he passed away on 12 August, just as the news that the world war had ended spread throughout the world. One of the finest contributions made to the Society’s work by Dr Arundale is best described by another slogan he invented — ‘Together Differently’. Repeatedly and insistently, he emphasized in his writings and talks that differences of outlook and opinion could only enrich the work of The Theosophical Society. Another important contribution was the emphasis he gave to straight Theosophy in the campaign which he initiated under that name. It cannot be said that any one of his contributions was more important than another, but the two mentioned above did unquestionably bring about a definite change in the minds and hearts of the membership, and sharply emphasized once more the freedom of individual thought inherent in Theosophical teachings. [18]

Rukmini wrote of his decline:

From 1942 onwards Dr. Arundale's health had been slowly deteriorating. He was such an uncomplaining, cheerful person that I never knew how seriously ill he was. He was highly diabetic but because of his principles would not take medicines which were produced by killing animals. I would pester him to come with me on my dance tours never realizing what a great effort he was making to please me. He passed away in 1945. Till the last moment I was so sure that he would be cured. He had always been there to take care of things but he was also preparing me in many ways - I can see it now - to stand on my own.[19]

Mrs. Arundale traveled to Haridwar and Rishikesh to immerse his ashes.[20]

Stamp from Maryland Lodge, 1937.

Honors, awards, and memorials

In 1935, Dr. Arundale was presented with the Subba Row Medal for his contributions to Theosophical literature.

The Shri Bharat Dharma Mahamandal of Benares [a university] conferred upon Dr. Arundale in 1942 the national honor of Vidya-Kalanidhi, which means "storehouse of art and wisdom.” The diploma was signed by His Highness the Maharajadhiraj of Darbhanga, the General President of the university.[21]

In 1937, the Maryland Lodge of the Theosophical Society in America produced stamps with the image of Dr. Arundale for use by American members.[22]

In 1932, an American lodge was established in Santa Barbara, California as the "Arundale Group."

Writings

Dr. Arundale wrote over 2200 articles for Theosophical periodicals, being especially prolific during the years that he served as President and as editor of The Theosophist. The Union Index of Theosophical Periodicals lists articles under George S Arundale, GS Arundale, and GSA.

These are books and pamphlets that he wrote, in chronological order.

• The Growth of National Consciousness in the Light of Theosophy. Madras: Theosophist Office, 1911. "Four lectures delivered at the Thirty-fifth annual convention of the Theosophical Society, held at Adyar, on December 27th, 28th, 29th and 30th, 1910."

• Brotherhood: a Series of Addresses. Benares, India: Rai Iqbal Narain Gurtu, 1913.

• Indian Students and Politics. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House, 1914. Adyar pamphlets; no. 44. Available at Canadian Theosophical Association.

• Thoughts on "At the Feet of the Master". Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1918. Second edition 1919. Available at Hathitrust.

• The Way of Service. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1913. Available at AnandGholap.net. Translated into German, French, and Tamil.

• Man's Waking Consciousness. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1920.

• The Real and the Unreal: being the four convention lectures delivered at Adyar at the forty-seventh anniversary of the Theosophical Society, December, 1922. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1923. Lectures by Annie Besant, C. Jinarajadasa, and George Arundale.

• Bedrock of Education. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1924.

• Thoughts of the Great, to Remind Us "We Can Make Our Lives Sublime"; gathered from time to time for personal guidance. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1924.

• The Ashrama Ideal. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1924. The Brahmavidya Library. no. The opening lecture of the second session of the Brahmavidyãshrama, Adyar, October 2, 1923.

• Understanding Godlike: Poem. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1925.

• Nirvana: a Study in Synthetic Consciousness. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1926. Wheaton: Theosophical Publishing House, 1978. Translated in to French, Spanish, German.

• "The Lord is Here". Adyar, Madras,India: Kalakshetra, 1927. Pamphlet.

• America: Her Power and Purpose. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1928. Booklet.

• The Life Magnificent. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1928.

• The Glory of Sex. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1928. Booklet.

• Some Intolerable Tyrannies. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1928. Booklet.

• Shadows and Mountains. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1928. Pamphlet.

• Go Your Own Way. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1928.

• Mount Everest: Its Spiritual Attainment. Adyar, Madras; London: Theosophical Publishing House, 1933, 1978. Translated into German, Russian, Dutch, Polish.

• My Work as President of the Theosophical Society: A Seven Year Plan; the Spirit of Youth. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1934. Translated into Dutch, Gujarati.

• Freedom and Friendship: the Call of Theosophy and the Theosophical Society. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1935.

• You. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House, 1935. Slightly revised - Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1973. Translated into French, German.

• The Science of Theosophy. London: The Theosophical Society in England, 1935.

• Theosophy as Beauty. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House, 1936. Adyar pamphlets ; no. 208. Available at Canadian Theosophical Association.

• Gods in the Becoming: A Study in Vital Education. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1936.

• Education for Happiness. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1938.

• The Warrior Theosophist. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1938.

• Kundalini: An Occult Experience. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1938. Wheaton: Theosophical Publishing House, 1974. Translated into Spanish.

• Peace and War in the Light of Theosophy: Quotations from Writings and Addresses of George S. Arundale. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1938.

• A Character for Indian Youth. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1939.

• The Lotus Fire: A Study in Symbolic Yoga. Adyar, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1939. Wheaton: Theosophical Publishing House, 1976.

• A Guardian Wall of Will: a Form of Tapas-Yoga. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1939. Pamphlet. Available on Anand Gholap Web page.

• A Fragment of Autobiography. Adyar, Madras,India: Kalakshetra, 1940.

• The Night Bell: Cases from the Case-book of an Invisible Helper. Adyar, Madras, India: Vasanta Press, 1940. Enlarged second edition, 1941.

• From Visible to Invisible Helping. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1941.

• Adventures in Theosophy. Adyar, Madras,India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1941.

• Conversations with Dr. Besant, September 20th-October 1st, 1933, on the high seas between Los Angeles & Suva. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1941. Pamphlet.

• Essentials of an Indian Education. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1942. Written with Annie Besant.

• Under the Weather. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House, 1943.

• Inaugural Addresses of Four Presidents of the Theosophical Society. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1946. Lectures by H. S. Olcott, Annie Besant, George S. Arundale, C. Jinarajadasa.

A commemorative book about Dr. Arundale was compiled by friends after his death:

• Personal memories of G.S. Arundale, third President of the Theosophical Society, by some of his numerous friends and admirers. London, Wheaton, IL [etc.] Theosophical Publishing House, 1967.

Notes

1. A. J. Hamerster, "Our New President," The American Theosophist 22.8 (August, 1934), 179-182.

2. A. J. Hamerster, "Our New President," The American Theosophist 22.8 (August, 1934), 179-182.

3. "George Sydney Arundale (1878 - 1945)," Theosophical Society, Adyar Web page. [1]

4. Clara Codd, So Rich a Life (Pretoria: Institute for Theosophical Publicity, 1956), 172.

5. A. J. Hamerster, "Our New President," The American Theosophist 22.8 (August, 1934), 179-182.

6. A. J. Hamerster, "Our New President," The American Theosophist 22.8 (August, 1934), 179-182.

7. Report of the Society for the Promotion of National Education for the Year 1918, (Adyar, Madras, India: Society for the Promotion of National Education, 1918). Kunz Family Collection, Records Series 25.01, Theosophical Society in America Archives.

8. ”Sarada Hoffman,” KutcheriBuzz Website http://www.kutcheribuzz.com/features/in ... sarada.asp, accessed February 28, 2012.

9. Joseph E. Ross, Spirit of Womanhood, privately published by the author, 2009: vii.

10. Rukmini Devi Arundale, "Rukmini on Herself," Rukmini Devi Arundale: Birth Centenary Commemorative Volume, Shakuntala Ramani, ed., (Chennai, India: The Kalakshetra Foundation, 2003), 26.

11. "George Sydney Arundale (1878 - 1945)," Theosophical Society, Adyar Web page. Available at Adyar Web page.

12. "George Sydney Arundale (1878 - 1945)," Theosophical Society Web page. Accessed Adyar Web page on November 4, 2013.

13. "News Items" The Messenger" 14.4 (August 1926), 65.

14. "In Australia" The Messenger" 14.4 (September 1926), 77.

15. "George Sydney Arundale (1878 - 1945)," Theosophical Society Web page. Accessed Adyar Web page on November 4, 2013.

16. "George Sydney Arundale (1878 - 1945)," Theosophical Society, Adyar Web page. [2]

17. "Olcott Scout Benefit Performance," The American Theosophist 22.8 (August, 1934), 188.

18. "George Sydney Arundale (1878 - 1945)," Theosophical Society, Adyar Web page. [3]

19. Rukmini Devi Arundale, "Rukmini on Herself," Rukmini Devi Arundale: Birth Centenary Commemorative Volume, Shakuntala Ramani, ed., (Chennai, India: The Kalakshetra Foundation, 2003), 64.

20. Ibid., 64

21. "Honor for the President," The American Theosophist 30.6 (June 1942), 142. Reprinted from The Theosophical Worker, February, 1942.

22. Stamp produced in 1937 by Maryland Lodge. Scanned from correspondence of George De Hoff to Sidney A. Cook. October 11, 1936. Records Series 08.05. Sidney A. Cook Papers. Theosophical Society in America Archives.

Additional resources

• The Theosophist, Vol. 66, No. 12, September 1945 (Commemorative Issue).

American Section, study course on Theosophy and Theosophical Society (Theosophical Society Archives).

• Dixon, Joy, Divine Feminine: Theosophy and Feminism in England (London: John Hopkins, 2001)

• Lutyens, Mary, Krishnamurti: The Years of Awakening (London: John Murray, 1975)

• Lutyens, Mary, The Life and Death of Krishnamurti (London: John Murray, 1990)

• Meduri, Avanthi (ed.), Rukmini Devi Arundale (1904-1968): A Visionary Architect of Indian culture and the Performing Arts (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 2005)

• Ransom, Josephine. The Seventy-Fifth Anniversary Book of the Theosophical Society. Theosophical Publishing House, 2005.