Western Women in leftist and national movements (1)

by sreenivasarao's blogs

January 17, 19__

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

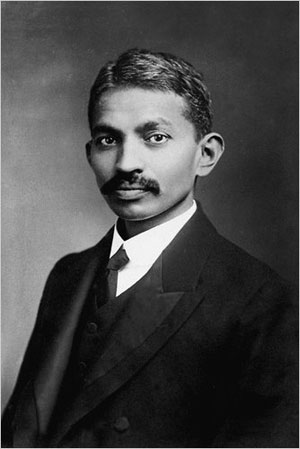

Before we continue with Roy’s saga in India we need to talk of the highly interesting phenomenon of the Western women participating in Indian independence struggle and in the leftist revolution as also getting involved with Asian men. It is one the fascinating aspects of the early decades of the twentieth century.

Such involvement of Western Women with men from their colonies and in matters that they considered detrimental to their mother-countries became a source of irritation and embarrassment to the European powers, especially to Great Britain.

Kumari Jayawardena in her Book The White Woman’s Other Burden: Western Women and South Asia during British Rule has written wonderfully well on this very engaging subject. Much of what is said here is based on her Book.

The British did not mind so long as the British women confined their activities to social issues such as education, health, charity, social reform and such other harmless activities. They could tolerate it as facet of women’s motherly nature. And, their caring for the weak, oppressed, downtrodden and a general concern for the deprived were viewed as giving expressions to virtues of Christian charity. The British authorities, either in Britain or in India, were not unduly worried about such pious preoccupations of their women as long as there was no breach of law and accepted norms of conduct.

White women as Theosophists were more daring in their questioning of the accepted ethnic and gender roles; and British did not relish the sight of their women of superior race and class wandering behind their Indian Gurus and singing their virtues and greatness. Though such women, surely, were annoying, they were not considered dangerous.

But, a more serious worry, anxiety and threat were the Western women socialists and communists. They were an anathema to the British rulers. Such impertinent women were viewed as the ultimate shame and embarrassment. On a more serious level they were regarded as serious threat to the colonial rule and to the security of the State.

In some cases, severe threats, punishments and deportation were imposed on such erring women to prevent them from further engaging in activities that could harm British rule and British image. A close watch and scrutiny was kept on western women engaged in anti-colonial activities and entangled with Asian men. And, they would be arrested if there was a perceived breach of law.

But, when the British and other western women were legally married to Indian men, their deportation would become a difficult and a ticklish issue. Because, in most cases the western women who got involved with Indian freedom movement or the leftist groups and with the Indian rebels, were, quite often, women coming from respectable middle class families. They usually were well educated having attended Universities and research institutions. They did not fall into the category of the run-of-the-mill ‘undesirable low class’ who could be put behind the bars routinely.

Further, such women who got involved with Asian men and leftist/anti-imperial activities were not only an embarrassment to the white-race, but also were a greater threat to the white race and the State. Such white–educated women were looked down as treacherous traitors who brought shame and betrayed ‘white womanhood’.

They were a more serious threat to the Empire than wayward men. Instead of helping the white men and their colonial rule these misguided women were undermining the very system that supported their life, their homes and their existence. Their unspeakable socialist views and their scandalous marriage, their illicit liaison with Asian men were despised as most reprehensible. They not only had gone astray but would also bring up half-breeds treading their dangerous path.

The British Intelligence, therefore, kept track of the Indian revolutionaries and their western women. And, in fact there were quite a number of such most horrid pairs.

The Western women – theosophists who claimed their rights as women to travel and follow their ‘faith’; and, the socialist women who came out to fight imperialism; formed the ‘feminist breakthrough’ by their rejection of the orthodox church and appropriation of alternative cultures and political ideologies.

Such ‘reprehensible’ alliances also caused discomfort to the Officers of the Empire placed in the colonies. The British dignity in the colonies also depended on their women’s allegiance to the Crown, to colonialism ; and on their modest behavior as polite ladies of refinement and culture. The worst sort of women, for the colonialists, were those white women who ‘traitorously’ rejected the moral duty of imperialism and embraced Asian men and Asian nationalism; for, they were seen not only to reject Empire but also the British men. The British masculine pride in such cases would surely be hurt.

Another irritating dimension of the British women marrying Indian men was the bringing up of their children according to Indian traditions and culture. That truly annoyed both the Colonial officers and the Church.

***

The situation in Berlin, Germany, was slightly different. Here, relationship or living-together of white woman with Indian male did not suffer from the ‘betraying-the Crown–syndrome’; although there were other issues related to political ideology and criminality. Berlin in the 1920s and 1930s was the hub of Indian students and Indian intellectuals, as also of those diverse revolutionary groups, each fighting the British rule in India, in its own manner, Indian students, in Berlin, openly engaged in anti-colonial gatherings; creating anti-British alliances; and even forging ties with Communists. The line between academic studies and radical politics was often blurred. Most of the Indian students got involved in radical anti-colonial politics.

A significant number of them on return to India grew into nationalist leaders. For instance; Dr. B R Ambedkar the doyen of Indian politics and the Social reform movement, for some time, studied Economics in the Bonn University during 1922-23. He was quite fluent in German (having taken it as a minor at Columbia University) and wrote his CV dated 21 February 1921 submitted to the University, in German. Please click here to view his hand-written CV, in German language. The other more well known of such caliber were: Dr. Zakir Hussain, who later rose to become the President of India; Dr. Ram Manohhar Lohia the stormy Socialist leader. And, Gangadhar Adhikari on return to India became the most influential theoretician in the Indian Communist Party from 1930s to 1940s. And, Dr. Meghnad Saha a noted physicist after returning to India played a major role as the nationalist organizer of science in India during 1930 to 1950.

Apart from radical politics, many Indian students got involved with German women. The instances of Indian students marrying German woman are too many to be recounted here. Just to cite a few cases: the brothers Anadi Nath Bahaduri and Prashath Bahaduri who studied in Germany during the 1920s returned to Calcutta with their German wives Margrit and Gerta. Apart from that, Abdul sattar Kheiri, Babar Mirza, Benoy Kumar Sarkar, and M N Roy all had German or Austrian wives. It appears that during 1930s at least six professors at the Aligarh University who had earlier studied in Germany had German wives.

Emilie Schenkl, Mrs Subhas Chandra Bose

Eimilie with daughter Anita

Much later, in the 1940s, one of the most notable cases was that of Subash Chandra Bose while attempting to destabilize British rule in India with German help had made Vienna, Austria as his base in Europe. Here at Vienna, Bose fell in love with Austrian woman Emilie Schenkl (26 December 1910 – March 1996) and married her secretly, according to Hindu rites. His marriage with Emilie Schenkl was kept a secret, even later. They had a daughter: Anita Bose (Pfaff). Since Bose was unable to bring his family to India in the midst of wartime Europe, he left Schenkl, with a note addressed to his elder brother in India, Sarat Bose, confirming the identity of his wife and their baby daughter; and asking for them to be accepted into the family, should he die in the war. Bose then moved from Germany to Southeast Asia in February 1943, and subsequently, he is believed to have died at the end of the war. And, after the war, Sarat Bose, his wife Bivabati and their three children, Sisir, Roma and Chitra, travelled to Vienna in the autumn of 1948 to meet Emilie and Anita. An emotional family meeting took place in Vienna when Sarat and Bivabati embraced Emilie and Anita into the Bose family. Sarat wanted Emilie and Anita to come to Calcutta to stay but since Emilie was the sole care for her aging mother, she could not leave Vienna

Please also see Emilie’s letter 26.7.1948 to Sarat Bose ]

But all such inter cultural marriages, as it usually happens, were not blissful or milk and honey. The relations within the marriage were tormented by inter-cultural differences, conflict of ideas and affiliations. The 1920s and 1930s were marked by ‘militant phase of feminism’. The western women that Virendranath Chattopadyaya and M N Roy came into contact had strong views on women’s liberation, both in the West and in India. They were quite eloquent in expressing their views. There were also differences on the political line taken by Indian men. The western women took their own theoretical positions on certain public issues, like birth control etc. Therefore, there were always passionate arguments. Even Roy had problems with Smedley. Her views on women’s rights particularly on the issue of abortion were more radical than that of any other Indian nationalist or reformers of 1920s.

Many Indian communists living in the West tended to project their relation with western women or political-comrades as a sign of ‘progress’ and modernity. The Indian men as socialists took a ‘progressive stand on the question of women’s equality’; but, their practice in day-to-day life differed from their stated principle. Roy also spoke and wrote that the modernization of Indian women was a ’historic necessity’ to transform the traditional outdated institutions which deprived women of their elementary human rights. In theory and in public stand he was much ahead of the contemporary scene. But, in his personal life and in his relations with the women in his group he did not seem to differ much from the contemporary male culture.

Kris Manjapra in his the impossible intimacies of M N Roy writes:

M N Roy’s life bore the stress marks of intimacies that were strange for his time. His intense private and professional relationship with Ellen Gottschalk, a German Jewish communist radical, was just one expression of the globe-straddling intimacies that disrupted the normative discourse of race, nation and colonial difference

**

The lot of western women who married fugitive Indian men – perpetually on ‘run’, very poor, nervous and highly insecure – was truly pathetic. And they did suffer a lot –- physically, mentally and emotionally. They also had to endure the pain, and humility of escapades and displacements. To put it very mildly, for a Western woman, such marriage was a highly unrewarding experience, to say the least.

Evelyn Trent Roy (wife of M N Roy) wrote that she was weary of ‘being hunted from place to place, country to country, of having to hide and always to be rewarded by a thick fog of suspicion and fear’. Similarly, Agnes Smedley, originally from Missouri, a partner of Virendranath Chattopadyaya in Berlin, recalled the extreme difficulties and ‘neurosis associated with anti-colonial inter-cultural lifestyle’. She wrote:

‘We were desperately poor, because Viren had no possessions. I sold everything I owned in order to get money… We skirted the problem by frequently moving, changing names. But, our debts and difficulties seemed to increase by geometric proportions. More than death, I feared insanity”.

She suddenly left Viren in 1928.

As for men, the strain of living as fugitives in a foreign land, without a sense of home, in a hostile environment was indeed very severe. Many Indian revolutionaries in West became nervous wrecks (e.g. Lala Hardayal in Berlin).

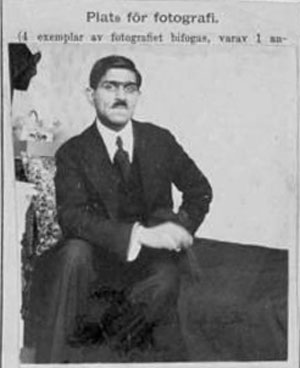

Virendranath ‘Chatto_ Chattopadhyaya -stockholm

M N Roy and Virendranath Chattopadyaya fell seriously ill. Roy was affected with infection of the inner ear and severe stomach illness. Virendranath also suffered from varieties of stomach illnesses. In addition, he suffered from paranoia. It appears he never took the meal outside for fear of being poisoned. Virendranath‘s final wife, Russian, Lidilia Kazunovskala remembered him as ‘always in a state of fleeing, full of disease, sorrow, tension, always on alert’. Viren eventually left Berlin in 1928. After another year of wandering he settled down in Moscow for some years. But soon after Stalin’s program of purging started he became nervous again, because he came to know that he was being watched for his ‘deviations from ‘orthodox Marxism-Leninism’ in his talks. He was called an Indian nationalist and not a true Soviet. His worst fears were, sadly, proved right. He was taken in Stalin’s purge of 1938-1940 and murdered.

***

During the early part of the twentieth century the marriages between Indian men and Western women seemed to be quite common. Apart from Viren and Roy there were quite a number who married Western women. Just to mention a few such, during 1920s and 1930s:

(a) Abani Mukherjee who was in M N Roy’s communist group was married to Rosa Fitingof, of Russian and Jewish origin. They had a son named Goga. Rosa Fitingof had joined the Communist Party in 1918; and was an assistant to Lydia Fotieva, Lenin’s Private Secretary when Abhani Mukherjee met her 1920. Fitingof and Abani Mukherjee were among the founding members of the Indian Communist Group formed at Tashkent. Later, she was also Roy’s interpreter.

During the 1930s, Abani Mukherjee worked at Moscow as an Indologist at the Oriental Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. Abhani Mukherjee fell a victim to the Great Purge in the late 1930s. He was arrested on June 2, 1937. He was assigned for the first category of repression (execution by firearms) in the list “Moscow-Center” and executed on October 28, 1937

(b) Dr, Anadi Bahaduri was member of Roy’s group in Berlin and was studying there for a Doctorate in Chemistry. His wife Margrit (born in 1907) of German Jewish origin continued to live in Calcutta after Bahaduri‘s death, teaching German.

(c) Also in Berlin was Saiyad Abdul Wahid Abai, an Indian Communist who married a German Jewish woman Kaethe Hulda Wolf.

(d) Another was Pandurang Sadashiv Khankhoje (1884-1966) from the rival group of Chattopadyaya. He was in the Ghadar Party in California; was named in the the Hindu-German Conspiracy; and, fled to Mexico in the early twenties (1920). He worked in the ministry of Agriculture in Mexico. He led the Mexican corn breeding program and was appointed Director of the Mexican Government’s Department of Agriculture. And, in 1936 he married a Belgian – Jeanne Alexandrine Sindic (born 1913).Both returned to India after independence. He settled down in Nagpur; and later went into politics. Pandurang Khankhoje died on January 22, 1967.

***

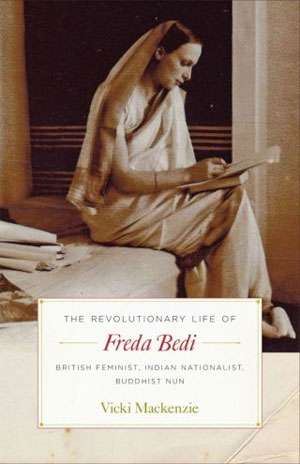

(e) And yet another was the Punjabi leader Baba Pyare Lal Bedi (B P Bedi), an author and philosopher, and his English wife Freda Houlston Bedi from Derbyshire (daughter of Francis Edwin Houlston and Nellie Diana Harrison).

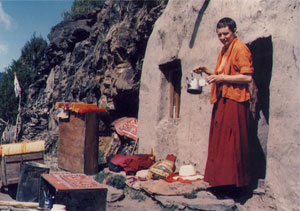

Freda (5 February 1911 – 26 March 1977), by any account, had an unusual life. She was born in Austria; raised and educated in England (Masters from St. Hugh’s in Oxford ) and in Sorbonne, Paris; married a Sikh at Oxford in 1933; and, in 1934 went to live in India where she spent the rest of her life.

Freda Marie Houlston was born at home in that 'tiny shop in the heart of old Derby', as she remembered it. It's still there, now a tanning salon looking out on the barren vista of a car park and dual carriageway which have cut Monk Street in two. The far section of Monk Street and adjoining terraces have survived largely unscathed in what is now, and was then, a working-class locality. The corner shops and pubs, the back alleys, the workshop yards, are all still evident, if some way from flourishing. Walking those streets is the closest you can get to communing with the Derby into which Freda was born. By the time her brother Jack came along the following year, the family had moved to Littleover, a neat Derby suburb -- and another step up in the world. During the First World War, they were living on Wade Avenue, in a home distinctly grander than the city centre terraced streets. It was also a safer place to live during the war. There was just one Zeppelin bombing raid on Derby which caused casualties, but the rail and engineering works were obvious potential targets, and Freda had distant childhood memories of hearing a wartime bomb drop on the city....

Every year, a handful of girls from Parkfields Cedars went on to university, but admissions to Oxford and Cambridge were rare. Freda hadn't intended to apply. She was persuaded by a school friend to keep her company in studying for and sitting the Oxford entrance exams. Freda was called for interview; her friend wasn't. She didn't get a place, but was told that if she spent some time in France she had a good chance of being admitted to study modern languages the following year.

It would have been no small matter for a seventeen-year-old schoolgirl to live abroad without any family at hand, but Freda's mother was supportive, and Freda herself showed the courage and initiative evident throughout her life. With the help of a pen friend, she managed to get a place, at no cost, at a high school in the cathedral city of Reims. It was close enough to the First World War battlefields to be able to visit her father's grave, 'overgrown with cat mint and Dorothy Perkins roses'. [4] She stayed with her friend's family and for a while in a boarders' hostel, and in spite of being homesick and deciding that her love of the French language didn't extend to its spoken form ('I couldn't stand the noise, the sound of French voices'), the confidence and experience she gained served its purpose; she secured admission to Oxford at the second attempt....

Freda emerged from St Hugh's with third-class honours, not quite as damning a statement of mediocrity then as it would be now, but clearly not the degree she hoped for. Neither Barbara nor Olive fared any better; all three women got thirds. [17]

The only substantial published account that Freda has left of the University, written during her last year for the Calcutta Review, pointed to what must have been a personal grievance, the disparity between wealthy and entitled students and those with much more limited resources.

1: The Suicide Club: The Lives of Freda: The Political, Spiritual and Personal Journeys of Freda Bedi -- EXCERPT, by Andrew Whitehead

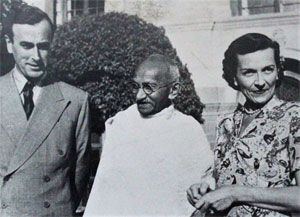

Before they moved to India, Andrew Whitehead writes, Baba Pyare Lal and Freda Bedi spent several months, during 1933-4, in Berlin where Baba Bedi had secured a research post. Their first child was born in Berlin. And in the autumn of 1934, the Bedis and their four month old baby reached India. After they settled down in Lahore – India, both got busily involved in the national independence movement during the 1930s and 1940s. The Bedis also became involved in left-wing politics and in journalism. They published several books and edited India-Analyzed (1934). And later, while participating in the national freedom movement, Freda was arrested and detained in Lahore jail with her children and with Gandhi. She was in prison for about six months during 1941-42 .

Her husband, Baba Bedi, it is said, spent long years (?) in prison for his activities in the struggle for independence. Baba Pyare Lal Bedi (1909–1993) later took to life of mysticism and spiritual healing.

After release from prison, they moved to Kashmir. Freda became the Professor of English at Srinagar in Kashmir. Both Freda and Baba Bedi were active in Kashmir during the 1940s; and were said to be close to Sheikh Abdullah and the National Conference. Baba Bedi is said to have drafted the party’s distinctly radical ‘New Kashmir’ manifesto.

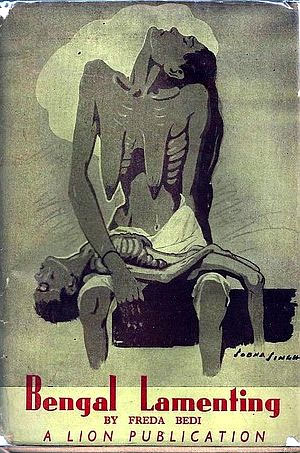

Andrew Whitehead (Freda Bedi’s biographer) mentions that following the great famine of Bengal in 1943, Freda toured, during January 1944, the districts most afflicted by famine. By then the famine had brought in its wake epidemic and disease. She took great risk of touring in the infected areas and moving among sick people dying out of sheer hunger and neglect. Freda wrote of her experiences in the famine stricken Bengal in her Book Bengal Lamenting. (Published in 1944)

Bengal Lamenting by Freda Bedi

In the words of Andrew Whitehead:

The book is more than a cry of pain, a call to pity, a picture of another tidal wave of tears that has wrenched itself up from the ocean of human misery. It is a demand for reconsideration on a national scale of a problem that cannot be localized, a plea for unity in the face of chaos, one more thrust of the pen for the right of every Bengali and every Indian to see his destiny guided by patriots in a National Government of the People.

After Independence, she edited Social Welfare, a magazine of the Ministry of Welfare; and was also appointed as the social worker of the United Nations Social Services, assigned to Burma. And much later, she was nominated as the advisor on Tibetan Refugees to the Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India.

In 1952, while working for the United Nations, Freda went to Rangoon; and, there she was drawn to Buddhism, learnt Vipassana meditation with Mahasi Sayadaw and Sayadaw U Titthila. Freda was one of the first Westerners to be initiated into Vipasana.

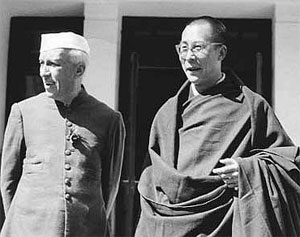

Nehru with the Dalai Lama

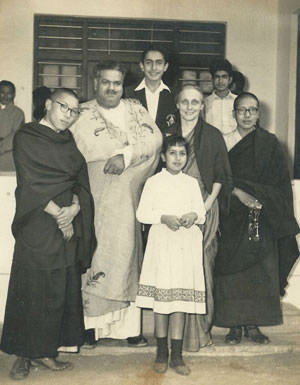

Then in 1959, when the Dalai Lama arrived in India along with thousands of Tibetans, Nehru asked Freda Bedi to help settle them; and, he then put her in charge of the Social Welfare Board.

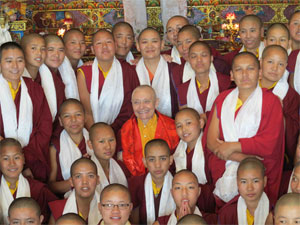

Freda was very drawn to Tibetan Buddhism and spent the rest of her life as a leader who looked after the welfare of Tibetans in India. And simultaneously, she took to practicing Tibetan Buddhism of the Kagyu School under the direct guidance of the Karmapa. She also became the Principal of a school established by the Dalai Lama in Delhi for young Tibetans. In 1963, Freda helped in setting up Karma Drabgyu Thargay Ling, a nunnery for Tibetan women in northern India. Besides, she set up a number of other organizations, such as : Friends of Buddhism, New Delhi; Tibetan Friendship Group; Young Lama’s Home School, Dalhousie; and Mahayana Monastic House.

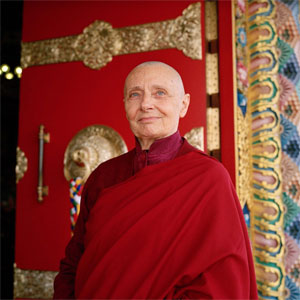

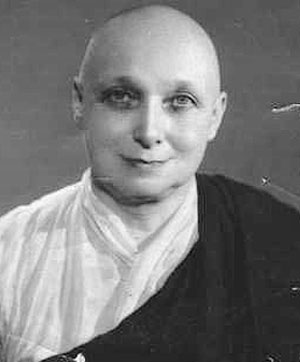

Freda Bedi

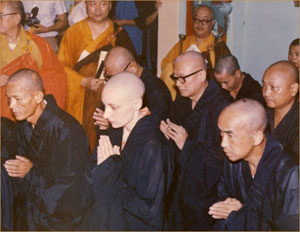

In 1966, Freda was ordained as a Buddhist monk by the Karmapa; and, was given the name Gelongma Karma Kechog Palmo or Sister Palmo. She was the first Western woman to be ordained in Tibetan Buddhism.

She was in contact with the Tibetans right from the moment they arrived in India; guiding and helping them in several ways. She arranged for education of number of young Tibetans in UK. Sister Palmo was a ‘Mother-figure’ ; and, was affectionately addressed by Tibetans as ‘Mummy’. It is said; Sister Palmo was uniquely influential, in a quiet way. She became an adept in Western Tibetan Buddhism; became a Dharma teacher; and guided many disciples.

As an ordained monk, Sister Palmo undertook several tours to West covering Britain, Europe, U.S.A. Canada and South Africa lecturing, giving Dharma instructions and initiations. She also supervised the activities of the Tibetan Buddhist centers set up in Scotland, USA and other places. In her efforts to spread the message of the Dharma, during her tours, she met and discussed with several leading thinkers. During her tour of 1974-5, she visited the Vatican and met the Pope.

She also turned into a Tibetan-English translator; translating number of Tibetan woks and hymns into English (the language ‘my birth-land’ – as she said). Her translations of A Garland of Morning Prayers – in the tradition of Mahayana Buddhism; and other prayers are quite well regarded.

Please also check : http://www.luxlapis.co.za/tibet.html for more.

In the later part of her life, she moved to a retreat in Sikkim, took to meditation intensely; wrote, and initiated and guided a spiritual movement that later became the ‘New Age’ movement.

Freda Houlston Bedi – Gelongma Karma Kechog Palmo was indeed an extraordinary person who lived an active and a purposeful life in the service of her fellow beings. She excelled in all the aspects of her life. And, in that she found her fulfillment.

She died peacefully in New Delhi on 26 March 1977, at the age of 66.

The Venerable Gelongma Karma Kechog Palmo (Freda Bedi) is revered as almost a Saint in Tibetan Buddhism.

According to Ms. Swati Jain, a Stupa is erected in Memory of Freda Bedi (Sister Palmo) at the Palpung Sherabling Monastic Seat in Bhattu, Kangra District, Himachal Pradesh.

Stupa for Freda

https://buoyantfeet.com/2015/12/28/a-bu ... l-pradesh/)

*

Freda Bedi was the mother of two sons, Ranga and Kabir Bedi (a film actor) and a daughter, Gulhima

(please check : http://www.luxlapis.co.za/lady.html )

(Please Check here for more on Freda Bedi – Andrew Whitehead’s page )

***

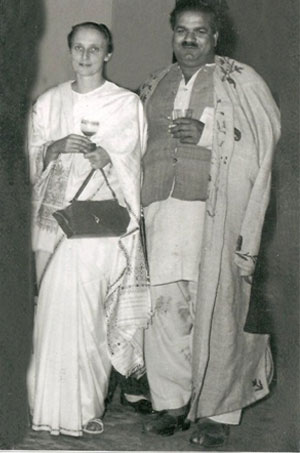

Alys Fiaz Ahmed

(f) Another couple in the left politics was the famous Urdu poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz of Lahore and his wife Alys George (September 22, 1914 – March 12, 2003) the daughter of a London bookseller. She and her sister Cristobel were active in leftist circles during the 1930s; and, both had worked with Krishna Menon in the India League at London. Her sister married Mohammad Din Tasser of Lahore (also in left movement). On a visit to India, Alys met and married Faiz and worked in politics and journalism. She was the founding member of the Democratic Women’s Association. He died in 1984. She continued to live in Pakistan as human rights activist.

[For more on Alys George and Faiz Ahmed Faiz please check their daughter Salima Hashmi‘s page at

http://old.himalmag.com/component/conte ... r-all.html

Salima Hashmi is a Lahore-based artist, cultural writer, painter, and anti-nuclear activist.]

***

(g) But the most sensational of all such relations was that of an early associate of M N Roy and the one who financed Roy’s health care in Switzerland as also his trip to India. He was Raja Brajesh Singh a wealthy prince hailing from the royal family of Kalakankar near Allahabad; and an Indian Communist. His affair with Josef Stalin’s daughter Svetlana became sensational.

Svetlana had an unlikely romance with Indian Communist Brajesh Singh Svetlana Alliluyeva3 bw

Svetlana Iosifovna Alliluyeva (later known as Lana Peters), was the youngest child and only daughter of Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin and Nadezhda Alliluyeva, Stalin’s second wife.

Svetlana, when she was 17, married (in 1943) Grigory Morozov, a fellow student from Moscow University, though Stalin hadn’t liked it. They had a son Josef (Iosif) in 1945. And, their divorce took place in 1947. Svetlana married, for the second time (in 1949), Yuri Zhdanov, the son of Stalin’s close associate. A daughter, Katherine, was born to them in 1950. And, soon thereafter they were divorced. Josef Stalin died in 1953.

In 1963, while Brajesh Sing was recuperating from bronchitis in Sochi, Russia, by the side of the Black Sea, he met Svetlana. The two began to talk about a book by Rabindranath Tagore that Svetlana had found in the hospital’s library. Singh was the most peaceful man Svetlana had ever met. He protested when the hospital wanted to kill the leeches they had used in his treatment, and he opened windows to let flies escape. When she told him who her father was, he exclaimed “Oh!” and never mentioned it again.

By then, Brajesh Sing had already married twice – to Lakshmi Devi and to Leea, an Austrian woman. When they met in 1963, Svetlana was about 37 years; and Brajesh Singh (said to be old enough to be her father) was about sixty, about twenty-three years elder to Svetlana. It is not clear whether they were married formally. It appears that the Soviet Primer Alexi Kosygin had strongly disapproved of Svetlana getting married to Brajesh Singh. (She however persisted in calling herself as Brajesh Singh’s wife.) They lived together for four years as man and wife at Sochi until Brajesh Singh died on 31 October 1966.

Svetlana ensured that Brajesh Singh was cremated according to Hindu rites. Thereafter; she decided to take his ashes to India for immersion in the Ganges. That took time because the Soviet leaders tried hard to dissuade her from making that journey. Finally, the arrangements for her travel to India were made at the highest level. And, that was not difficult since Brajesh Singh’s nephew Dinesh Singh was a confidant of then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and was also a member of her council of ministers.

Svetlana arrived in India on 20 December 1966 with ashes of Brajesh Sigh. She stayed with Brajesh’s family at their ancestral royal home at Kalakankar near Allahabad (UP). After a couple of days, on 25 December 1966, Brajesh’s ashes were immersed in the Holy Ganges, with Svetlana watching the ritual, from the shore, dressed in widow’s white sari.

She lived happily with Brajesh’s extended family; and got on very well with all its members. She wanted to stay back in India; and, Brajesh’s family was also willing and happy to let her stay with them. Svetlana asked Dinesh Singh (Brajesh’s nephew) to use his influence with Indira Gandhi to let her stay in India. But the Soviet Government insisted that she should be back in Moscow before the end of March 1967. Indira Gandhi, not daring to antagonize the Soviets, advised Svetlana, through Dinesh, to return to Russia. Exasperated, Svetlana approached socialist Rammanohar Lohia in Allahabad for help so that she could stay in India and build a memorial for Brajesh. He promised to help; but could do very little.

Svetlana then reached New Delhi for making arrangements for her travel to Moscow; and stayed there at the Soviet Embassy where Ambassador Nikolai Benediktov was advising her to return home. Next day, on the evening of 6 March 1967, Svetlana went out to finalise her travel arrangements; but, she asked the taxi to drive straight to the American embassy. The embassy had shut for the day. She told the duty officer who she was and what she wanted. In panic, the duty officer rang up Ambassador Chester Bowles and told him that he must come to his office immediately to deal with a matter that could not be discussed on the phone. Mr Bowles arrived, talked to Svetlana and gave her a lined pad to write down why she wanted to go the US; and, not to her own country.

[Ambassador Chester Bowles, later recalled: In about two hours she put together a very eloquent sixteen to eighteen page statement in excellent English; a dramatic story of her life, who her father was, who her mother was, and why she wanted to leave Russia and come to America. Please see; India & the United States: Politics of the Sixties by Kalyani Shankar. P.387 to 393]

While Svetlana was writing her piece, Ambassador Bowles sent an “Eyes Only” telegram to the Secretary of State Dean Rusk explaining the situation and asking for instructions. He took care to conclude his cable with the words: “If I do not hear from the State Department by midnight (Indian time), I would, on my responsibility, give her the visa.”

According to the Ambassador’s subsequent account of the incident, as he had expected, there was not a word from Washington by the deadline. So he arranged to send Svetlana to the airport in the company of a CIA officer to catch a flight to Rome.

Only after she had reached Rome safely did the sensational news of her dramatic great escape was leaked to the Press.

There was, of course, a huge uproar in Moscow and in New Delhi; the US government blandly explained that it merely helped Svetlana on humanitarian grounds.

After a brief stay in Switzerland, she flew to the US. Upon her arrival in New York City in 1967, the then 41-year-old said, “I have come here to seek the self-expression that has been denied to me for so long in Russia.”

smiles for photographers at her press conference April 26.

Three days after she landed in America, Svetlana sent her children in Moscow (Iosif and Yekaterina, twenty-one and sixteen) a long letter. Soviet Communism, she said, had failed as an economic system and as a moral idea. She couldn’t live under it. “With our one hand we try to catch the moon itself, but with another one we are obliged to dig out potatoes the same way it was done a hundred years ago,” she wrote. She urged Iosif to study medicine and Yekaterina to continue to pursue science. “Please, keep peace in your hearts. I am only doing what my conscience orders me to do.”

(http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/ ... s-daughter)

The note that Svetlana wrote while in the US Embassy at New Delhi along with her “Twenty Letters to a Friend” was published within months of her arrival in the US; and it became a best-seller. The book in the form of a series of letters to her friend, the physicist Fyodor Volkenstein, described her family’s tragic history. The message of the book, it seemed, was that being one of Stalin’s relatives was nearly as terrible as being one of his subjects.

According to Brajesh Singh’s family in India, Svetlana did not forget her commitment for the memorial for Brajesh: “She kept sending money for many years for a hospital in Kalakankar village in Brajesh’s name, until it was taken over by the government”.

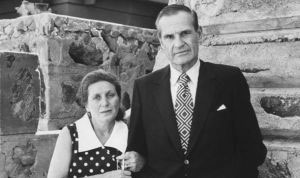

Svetlana settled down in Princeton New Jersey, where she lectured and wrote. From 1970–73, she was married to American architect William Wesley Peters with whom she had a daughter, Olga. Svetlana died in Richland Center, Wisconsin, U.S, from complications arising from colon cancer, on 22 November 2011, at the age of eighty-five (28 February 1926 to 22 November 2011).

Svetlana married American Wesley Peters, with whom she had a daughter

For more please do read a detailed article :

My Friend, Stalin’s Daughter by Nicholas Thompson which appeared in the March 31, 2014 Issue of The New Yorker.

***

Let’s talk about the intertwining lives of what was called as the Left Quartet – M N Roy, Evelyn Trent, Virendranath Chattopadyaya and Agnes Smedley, in the subsequent parts.

_______________

Sources and References

The White Woman’s Other Burden: Western Women and South Asia During British Rule by Kumari Jayawardena

Age of Entanglement by Kris Manjapra

Many pages of the Wikipedia

Socialism of Jawaharlal Nehru by Rabindra Chandra Dutt

India & the United States: Politics of the Sixties by Kalyani Shankar

How Stalin’s daughter defected in India–

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-15936172

The Lives of Agnes Smedley by Ruth Price

http://www.sacu.org/smedley.html

Trials that Changed History: From Socrates to Saddam Hussein by M.S. Gill (Chapter 19- Agnes Smedley)

Freda Bedi (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Freda_Bedi )