by Wikipedia

Accessed: 4/11/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

The Honourable

Maurice Frederick Strong

PC, CC, OM, FRSC, FRAIC

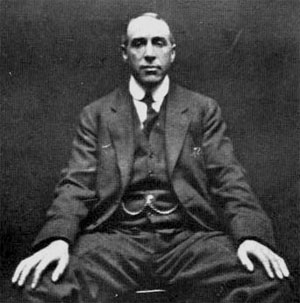

Maurice Frederick Strong

Maurice Strong having received the Four Freedoms Award for Freedom from Want in 2010

Personal details

Born April 29, 1929

Oak Lake, Manitoba, Canada

Died November 27, 2015 (aged 86)

Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Nationality Canadian

Spouse(s) Pauline Olivette (m. 1950, div. 1980)

Hanne Marstrand (m. 1981, sep. 1989)[1][2]

Parents Frederick Milton Strong, Mary Fyfe

Residence Crestone, Colorado, U.S. (1972-1989)

Lost Lake, Ontario[2]

London, United Kingdom

Beijing, China

Occupation Businessman, public administrator, UN official[3]

Maurice Frederick Strong, PC, CC, OM, FRSC, FRAIC (April 29, 1929 – November 27, 2015) was a Canadian oil and mineral businessman and a diplomat who served as Under-Secretary-General of the United Nations.[4][5]

Strong had his start as an entrepreneur in the Alberta oil patch and was President of Power Corporation of Canada until 1966. In the early 1970s he was Secretary General of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment and then became the first executive director of the United Nations Environment Programme. He returned to Canada to become Chief Executive Officer of Petro-Canada from 1976 to 1978. He headed Ontario Hydro, one of North America's largest power utilities, was national president and chairman of the Extension Committee of the World Alliance of YMCAs, and headed American Water Development Incorporated. He served as a commissioner of the World Commission on Environment and Development in 1986[6] and was recognised by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as a leader in the international environmental movement.[7]

He was President of the Council of the University for Peace from 1998 to 2006. More recently Strong was an active honorary professor at Peking University and honorary chairman of its Environmental Foundation. He was chairman of the advisory board for the Institute for Research on Security and Sustainability for Northeast Asia.[8] He died at the age of 86 in 2015.[9]

Childhood and youth

Maurice Strong was a child during the Great Depression, enduring serious poverty. His father was laid off at the beginning of the Depression era and thereafter supported his family on odd jobs; his mother succumbed to mental illness and died in a mental hospital. He was born in Oak Lake, Manitoba, a town on the Canadian prairies on the mainline of the Canadian Pacific Railway.[10] He is a distant cousin of Anna Louise Strong.[11][12]

Strong later said that growing up during the Depression radicalized him and that he considered himself to be "a socialist in ideology, a capitalist in methodology." He dropped out of high school at the age of 14 and did not go to college. Despite the lack of formal education, he was able to become CEO of many companies.[13]

Business

In 1948, when he was nineteen, Strong was hired as a trainee by a brokerage firm, James Richardson & Sons, Limited of Winnipeg where he took an interest in the oil business, being transferred as an oil specialist to Richardson's office in Calgary, Alberta. There he made the acquaintance of one of the figures in the oil industry, Jack Gallagher, who hired him as his assistant. At Gallagher's Dome Petroleum, Strong occupied several roles including vice president of finance, leaving the firm in 1956 and setting up his own firm, M.F. Strong Management, assisting investors in locating opportunities in the Alberta oil patch.[14]

In the 1950s, he took over a small natural gas company, Ajax Petroleum, and built it into one of the companies in the industry, Norcen Resources. This attracted the attention of one of Canada's principal investment corporations with interests in the energy and utility businesses, Power Corporation of Canada. It appointed him initially as its executive vice president and then president from 1961 until 1966.

In 1976, at the request of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, Strong returned to Canada to head the newly created national oil company, Petro-Canada.[15]

He was slated to stand as a candidate for the Liberal Party of Canada in Scarborough Centre in the 1979 federal election, but chose to abandon the race, returning to private enterprise[16] to manage AZL Resources,[17] a Denver oil promoter that he had previously acquired,[17] where he served as chairman and was the largest shareholder. In 1981, Strong was sued for allegedly hyping the stock ahead of a merger that eventually failed. Strong settled for $4.2 million at the insistence of his insurance company.[18] AZL merged with Tosco Corporation from which Strong acquired the 160,000 acres (65,000 ha) Baca Ranch in Colorado which would house Strong's Manitou Foundation.[17]

Strong later became chairman of the Canada Development Investment Corporation, the holding company for some of Canada's principal government-owned corporations. In 1992, he became Chairman of Ontario Hydro.[17] a Denver oil promoter that he had previously acquired,[17]

Charles Lynch noted that Strong "tended to fare better than the companies and institutions that have used his talents."[3] He was said to have become a billionaire as a result of his several ventures,[17] a Denver oil promoter that he had previously acquired,[17] but in 2010 he said that he had "never been anywhere close to being [so]."

American Water Development

On December 31, 1986, Strong founded American Water Development Incorporated (AWDI) which he controlled along with his associates, William Ruckelshaus, Richard Lamm, Samuel Belzberg, and Alexander Crutchfield Jr.[19] It filed an application with the District Court for Water Division 3 in Alamosa, Colorado[20] for the right to pump underground water from the lands of the Luis Maria Baca Grant No. 4 and other lands in Saguache County, Colorado in Colorado's San Luis Valley and sell it to water districts in the Front Range Urban Corridor of Colorado. The project was opposed by neighboring water rights owners, local water conservation districts, the Colorado Department of Natural Resources and the National Park Service who alleged the project would affect others' water rights and cause significant environmental damage to nearby wetland and sand dune ecosystems by reducing the flow of surface water.[19] After a lengthy trial, which ended in 1992, Colorado courts ruled against AWDI and required payment of the portion of the objectors' legal fees, $3.1 million, which were spent fighting AWDI's attempt to appropriate surface water for beneficial use.[20][21] While this was going on, Strong exited the company.

Molten Metal Technology

Maurice Strong was a director of Molten Metal Technology, Inc., an environmental technology company founded in 1989 that claimed to have innovative technology that could be used to recycle hazardous waste into reusable products. During the years 1992-1995, this innovation attracted approximately $25 million in research grants from the United States Department of Energy. Throughout the period of March 28, 1995 – October 18, 1996, (known as the "class period"), Molten Metal artificially inflated the price of their stock by materially misrepresenting the capability of its technology, namely through a series of public announcements. As of March 11, 1996 Strong owned approximately 40,000 shares of stock and another 262,000 shares were owned by a company of which Strong was Chairman.[22] The company filed for bankruptcy and the case was settled for $11.8 million, without a ruling of wrongdoing.[23]

United Nations work

Strong first met with a leading UN official in 1947 who arranged for him to have a temporary low-level appointment, to serve as a junior security officer at the UN headquarters in Lake Success, New York. He soon returned to Canada, and with the support of Lester B. Pearson, directed the founding of the Canadian International Development Agency in 1968.

Stockholm Conference

In 1971, Strong commissioned a report on the state of the planet, Only One Earth: The Care and Maintenance of a Small Planet,[24] co-authored by Barbara Ward and Rene Dubos. The report summarized the findings of 152 leading experts from 58 countries in preparation for the first UN meeting on the environment, held in Stockholm in 1972. This was the world's first "state of the environment" report.

The Stockholm Conference established the environment as part of an international development agenda. It led to the establishment by the UN General Assembly in December 1972 of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), with headquarters in Nairobi, Kenya, and the election of Strong to head it. UNEP was the first UN agency to be headquartered in the third world.[25] As head of UNEP, Strong convened the first international expert group meeting on climate change.[26]

Strong was one of the commissioners of the World Commission on Environment and Development, set up as an independent body by the United Nations in 1983.

Earth Summit

Strong's role in leading the U.N.'s famine relief program in Africa was his first in a series of U.N. advisory assignments, including reform and his appointment as Secretary General of the U.N. Conference on Environment and Development, best known as the Earth Summit, and held in Rio de Janeiro from June 3 to June 14, 1992.[27][28] According to Strong, participants at the Rio Conference adopted sound principles but did not make a commitment to action sufficient to prevent global environmental tragedy, committing to spend less than 5% of the $125 billion he felt appropriate for environmental projects in developing nations. He was seconded in that opinion by U.N. Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali who stated to the delegates, "The current level of commitment is not comparable to the size and gravity of the problems,"[29]

After the Earth Summit, Strong continued to take a leading role in implementing the results of agreements at the Earth Summit through the establishment of the Earth Council, acting as co-chair of the Earth Charter Commission at the outset of the Earth Charter movement, his chairmanship of the World Resources Institute, membership on the board of the International Institute for Sustainable Development, the Stockholm Environment Institute, The Africa-America Institute, the Institute of Ecology in Indonesia, the Beijer Institute of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and others. Strong was a longtime Foundation Director of the World Economic Forum, a senior advisor to the president of the World Bank, a member of the International Advisory of Toyota Motor Corporation, the Advisory Council for the Center for International Development at Harvard University, the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, the World Conservation Union (IUCN), the World Wildlife Fund, Resources for the Future and the Eisenhower Fellowships. His public service activities were carried out on a pro bono basis made possible by his business activities, which included being chairman of the International Advisory Group of CH2M Hill,

CH2M HILL, also known as CH2M, was a global engineering company that provided consulting, design, construction, and operations services for corporations, and federal, state, and local governments. The firm's headquarters was in Meridian, an unincorporated area of Douglas County, Colorado, in the Denver-Aurora Metropolitan Area.

The postal designation of nearby Englewood was commonly listed as the company's location in corporate filings and local news accounts. As of December 2016, CH2M had approximately 20,000 employees and revenues totaled $5.24 billion.[2]

In December 2017, it was announced that CH2M had been acquired by Jacobs Engineering Group, a Dallas engineering firm, reportedly for $3.3 billion. [3]...

The company developed, maintains and publishes its own method for managing projects for clients, called the CH2M Hill Project Delivery System, which may be found at popular internet book retailers.[9] As a firm specializing in project management, CH2M Hill has been associated in several large, complex projects around the world. In 2005, a CH2M Hill joint venture known as Kaiser Hill decommissioned and closed a former nuclear weapons facility at the Rocky Flats site in Colorado (former Rocky Flats Plant).Cleanup began in the early 1990s,[6][7][8] and the site achieved regulatory closure in 2006.[9] The cleanup effort decommissioned and demolished over 800 structures; removed over 21 tons of weapons-grade material; removed over 1.3 million cubic meters of waste; and treated more than 16 million gallons of water. Four groundwater treatment systems were also constructed.[10] Today, the Rocky Flats Plant is gone. The site of the former facility consists of two distinct areas: (1) the "Central Operable Unit" (including the former industrial area), which remains off-limits to the public as a CERCLA "Superfund" site, owned and managed by the U.S. Department of Energy,[11] and (2) the Rocky Flats National Wildlife Refuge, owned and managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

-- Rocky Flats Plant, by Wikipedia

In Singapore, the company was part of a joint venture to replace the country's sanitary services infrastructure.[10] The new Singapore Deep Tunnel System was designed to improve reliability, ease, and economy of operation, and to help handle Singapore's increasing waterfront utilization.[11] CH2M Hill assisted in reconstruction efforts along the US Gulf Coast in the wake of Hurricane Katrina.[12]

Its main assignments included providing temporary housing, debris removal, and other services. Other large projects include a $660 million gas fired power plant in Australia, in conjunction with General Electric,[13] and an $11.7 billion project to relocate American military bases in Korea.[14]

In August 2007, the Panama Canal Authority selected CH2M Hill to manage the $5.25 billion Panama Canal expansion project, which will add new locks to the Pacific and Atlantic ends of the canal and allow Post Panamax ships passage through the canal for the first time.[15][16] In 2009, a CH2M Hill consortium was named program partner to oversee construction of the Crossrail[17] project to expand London's transit system.

On August 30, 2006, as part of joint venture CLM, CH2M Hill was a supplier for the London 2012 Olympics.[18] The other two members of the venture are project management service provider Mace Group and Laing O'Rourke, the largest privately owned construction firm in the United Kingdom.

In 2008, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) contracted a CH2M Hill company, CH2M Hill Plateau Remediation Company, LLC (CHPRC), to manage deconstruction and remediation of the Central Plateau on the Hanford Nuclear Site in eastern Washington, one of the world's largest environmental cleanup projects. The project focused on shrinking the environmental footprint of the Hanford Site from a 586-square-mile (1,520 km2) area (large enough to fit the city of Los Angeles) to 75 square miles (190 km2) or less.Hanford is currently the most contaminated nuclear site in the United States[9][10] and is the focus of the nation's largest environmental cleanup.[2]

-- Hanford Site, by Wikipedia

Acquisitions

Key acquisitions include Black, Crow & Eidsness (a southeast engineering firm in the United States) in 1977,[19], Gee & Jensen (a Ports and Harbor firm based in Florida) in August 2002,[20] DeMil International (a weapons destruction firm based in the United States) in 2002,[21] EHS Consultants Ltd (a consulting firm based in Hong Kong),[22], BBS Corporation (an environmental engineering firm based in Ohio) in October 2005.[23]

On September 7, 2007, CH2M HILL finalized the purchase of most of the components of VECO, an Alaska based firm specialising in services to the oil, gas, and energy sector that had become embroiled in the Alaska political corruption probe.[24] In December 2007, CH2M Hill acquired Trigon EPC.[25] In March 2008, CH2M Hill acquired Texas based Goldston Engineering, a company specialising in marine and coastal transportation engineering services.[26]

In 2014, CH2M HILL acquired TERA Environmental Consultants, a Canadian environmental consulting firm that has worked with pipeline and powerline clients and oil and gas companies for 30 years.[27]

-- CH2M Hill, by Wikipedia

Strovest Holdings, Technology Development Inc., Zenon Environmental, and most recently, Cosmos International and the China Carbon Corporation.

Strong lobbied to change NGO perspectives on the World Bank.[30] He is believed by some to have inspired the works of former U.S. Vice President Al Gore on climate change. In 1999 Strong took on the task of trying to restore the viability of the University for Peace, headquartered in Costa Rica, established under a treaty.[31] The reputation of the University of Peace was at risk because the organization had been subjected to mismanagement, misappropriation of funds and inoperative governance. As chairman of its governing body, the Council, and initially as rector, Strong led the process of revitalizing the University for Peace and helped to rebuild its programs and leadership. He retired from the Council in the spring of 2007.

From 2003 to 2005, Strong served as the personal envoy to U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan to lead support for the international response to the humanitarian and development needs of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea.[32]

University for Peace

The University for Peace was established in 1980 by the General Assembly of the United Nations. Maurice Strong became director in 1999 where he was at the center of further controversy, particularly in reference to the eviction of the beloved radio station Radio for Peace International (RFPI), the fleeing of the Earth Council in 2003, and the implementation of military training programs on campus. Strong was a board member of the Earth Council, which was created as an international body to promote the environmental policies established at Earth Summit in 1992. The Costa Rican government donated more than 20 acres of land to be used by Earth Council, but when plans for building fell through, it was allegedly sold for $1.65 million. Earth Council temporarily moved to the UPEACE campus until December 2003 when it moved to Canada in the midst of government accusations and demands for $1.65 million. RFPI was served with an eviction notice in July 2002 based on claims the station was operating without proper permits, which RFPI refuted. Those close to the situation claim that UPEACE officials didn't approve of the criticism they were receiving from the station and took matters into their own hands, when power to the building was cut and a wire fence put up around the perimeter.[33]

2005 Oil-for-Food scandal

In 2005, during investigations into the U.N.'s Oil-for-Food Programme, evidence procured by federal investigators and the U.N.-authorized inquiry of Paul Volcker showed that in 1997, while working for Annan, Strong had endorsed a check for $988,885, made out to "Mr. M. Strong," issued by a Jordanian bank. It was reported that the check was hand-delivered to Mr. Strong by a South Korean businessman, Tongsun Park, who in 2006 was convicted in New York federal court of conspiring to bribe U.N. officials to rig Oil-for-Food in favor of Saddam Hussein. Mr. Strong was never accused of any wrongdoing.[34] During the inquiry, Strong stepped down from his U.N. post, stating that he would "sideline himself until the cloud was removed."

The affair was said to have arisen from "the tangled nest of personal relationships, public-private partnerships, murky trust funds, unaudited funding conduits, and inter-woven enterprises that the modern U.N. has come to embody" in which Strong had a major role.[11] In reply, Strong stated that "everything I did, I checked it out carefully with the U.S."[34]

Shortly after this, Strong moved to an apartment he owned in Beijing, where he appeared to have settled.[34] He said that his departure from the U.N. was motivated not by the Oil-for-Food investigations, but by his sense at the time, as Mr. Annan's special adviser on North Korea, that the U.N. had reached an impasse. "It just happened to coincide with the publicity surrounding my so-called nefarious activities," he insists. "I had no involvement at all in Oil-for-Food ... I just stayed out of it."[34] In Volcker's September 7 report he concluded, "While there is evidence that Iraqi officials tried to establish a relationship with Mr. Strong, the Committee has found no evidence that Mr. Strong was involved in Iraqi affairs or matters relating to the Programme or took any action at the request of Iraqi officials." [35]

UN Secretary General's tribute

Secretary-General of the United Nations Kofi Annan, near the end of his term, paid the following tribute to Maurice Strong:

Looking back on our time together, we have shared many trials and tribulations and I am grateful that I had the benefit of your global vision and wise counsel on many critical issues, not least the delicate question of the Korean Peninsula and China's changing role in the world. Your unwavering commitment to the environment, multilateralism and peaceful resolution of conflicts is especially appreciated.

Later involvement

In 2010, Strong described the nature of his activities at that time:

I am retired from all my official roles, but I am still very active. I have close relationships at the UN. I don't have any role at the UN, but I'm still quite cooperative with a number of UN activities, in particular to China and that region. I don't have any government responsibilities or formal role. I continue to be active, though.[36]

In 2012 for Rio+20 he contributed to a book by Felix Dodds and Michael Strauss entitled Only One Earth - the Long Road via Rio to Sustainable Development, which reviewed the last forty years and the challenges for the future. He attended the conference, for which the United Nations Development Program paid all his travel expenses.[37]

Controversy

Maurice Strong was no stranger to skepticism and criticism as a result of his lifelong involvement in the oil industry, juxtaposed with his heavy ties to the Environment. Some wonder why an "oilman" would be chosen to take on such coveted and respected environmental positions. One of Strong's companies, Desarrollos Ecologicos (Ecological Development), built a $35 million luxury hotel within the Gandoca-Manzillo Wildlife Refuge where development is restricted and must be approved by the Kekoldi Indian Association, which it was not. "He (Strong) is supporting Indians and conservation around the world and here he's doing the complete opposite," lamented Demetrio Myorga, President of the Kekoldi Indian Association.[38]

Further skepticism arose due to his continual promotions to titles of power, likely due to his political connections. Additionally, Strong was involved in several legal battles and scandals over the years where he conveniently seemed to recuse himself from the situation before being held personally responsible.[39]

Death, funeral and memorial services

Strong died at the age of 86 on November 27, 2015[40] in Ottawa, Ontario.[41] A funeral service was held there in early December 2015,[41] with a public memorial service occurring in late January 2016 across from Parliament Hill.[42][43] The service was broadcast on CPAC,[44] and among those who spoke were James Wolfensohn, Adrienne Clarkson, John Ralston Saul and Achim Steiner.[45] Written tributes from Mikhail Gorbachev, Gro Harlem Bruntland and Kofi Annan were also sent.[45]

Impact

While unremarkable in appearance,[46] Strong was said to have "an astonishing network" that connected diverse interest groups.[46] One observer described his "scarcely-concealed delight in explaining his often Machiavellian political manoeuvrings."[46]

In the environmental movement, he was instrumental in promoting government funding and entry into international meetings for environmental non-governmental organizations.[46]

Honours and awards

Maurice Strong received a number of honours, awards and medals. He received 53 honorary doctorate degrees and honorary visiting professorships at 7 universities.

Honours appearing in the Canadian order of precedence are:

Companion of the Order of Canada 1999[47]

Order of Manitoba 2005

Queen Elizabeth II Silver Jubilee Medal 1977

125th Anniversary of the Confederation of Canada Medal 1992

Queen Elizabeth II Golden Jubilee Medal 2002[48]

Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal 2012[49]

Order of the Polar Star (Sweden) 1996

Order of the Southern Cross (Brazil) 1999[50]

Commander of the Order of the Golden Ark (Netherlands) 1979

Other honours and awards include:

• 1 July 1992: Sworn in as a Member of the Queen's Privy Council for Canada.

• 2003: Public Welfare Medal from the US National Academy of Sciences: First non-US citizen to receive the medal, 2007[51]

• 2002:Jack P. Blaney Award for Dialogue by the Simon Fraser University Morris J. Wosk Centre for Dialogue[52]

• 2002: Carriage House Center on Global Issues: Candlelight Award[53]

• 1995: IKEA Environmental Award[citation needed]

• 1994: Asahi Glass Foundation Award: Blue Planet Prize[54]

• 1994: Jawaharlal Nehru Award for International Understanding [55]

• 1993: International St. Francis Prize for the Environment

• 1993: Alexander Onassis Delphi Prize[56]

• 1989: Pearson Medal of Peace [57]

• 1981: Charles A. Lindbergh Award[58]

• 1977: Henri Pittier Order of Venezuela [59]

• 1975: National Audubon Society Award[60]

• 1974: Tyler Environmental Prize[61]

• 1967: Honorary doctorate from Sir George Williams University, which later became Concordia University.[62]

• International Saint Francis Prize, Fellow

• Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada (FRSC) [63]

• Fellow of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (FRAIC) [64]

• Honorary board member, David Suzuki Foundation[65]

• Distinguished Fellow, International Institute for Sustainable Development[66]

John Ralston Saul dedicated his polemic Voltaire's Bastards: The Dictatorship of Reason In The West to Strong.

Papers

Strong's papers are archived at the Environmental Science and Public Policy Archives in the Harvard Library.

References and notes

1. Raverty, Aaron Thomas (2014). Refuge in Crestone: A Sanctuary for Interreligious Dialogue. London: Lexington Books. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-7391-8375-5.

2. Strong Papers 2003.

3. Lynch, Charles (September 30, 1982). "Guy on the Street refinancing Dome". Montreal Gazette. p. B4. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

4. E Masood (2015) Maurice Strong, Nature 528(7583), 480.

5. https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=r ... 28,8434969 Article in The Vindicator June 30, 2000

6. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-05-14. Retrieved 2011-01-01.

7. http://cmsdata.iucn.org/downloads/repor ... alogue.pdf

8. "Short Biography". http://www.mauricestrong.net. Retrieved 2014-06-03.

9. "The World Mourns One of its Greats: Maurice Strong Dies, His Legacy Lives On". Archived from the original on 2016-02-20.

10. Strong, Maurice; Kofi Annan (2001). Where on Earth are We Going (Reprint ed.). New York, London: Texere. pp. 48–55. ISBN 1-58799-092-X. The Depression was one of the great shaping forces in my life ...

11. Rosett, Claudia; Russell, George (February 8, 2007). "At the United Nations, the Curious Career of Maurice Strong". Fox News.

12. https://books.google.ca/books?id=ui2OTJ ... =PA255&dq="maurice+strong"+"anna+louise"&source=bl&ots=R379TIJFnC&sig=ACfU3U0IdxlnhJw2pbRCGKARYTLyJ5tuzQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjqlLfK86LgAhULy1kKHaOFBlYQ6AEwEXoECAkQAQ#v=onepage&q="maurice%20strong"%20"anna%20louise"&f=false

13. "WHO IS MAURICE STRONG? The adventures of Maurice Strong & Co. illustrate the fact that nowadays you don't have to be a household name to wield global power", National Review, September 1, 1997

14. Strong, Maurice; Kofi Annan (2001). Where on Earth are We Going (Reprint ed.). New York, London: Texere. pp. 75–89. ISBN 1-58799-092-X. The Depression was one of the great shaping forces in my life ...

15. "Maurice F. Strong Is First Non-U.S. Citizen To Receive Public Welfare Medal, Academy's Highest Honor". National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2008-01-20.

16. Clarkson, Stephen (2005). The Big Red Machine: How the Liberal Party Dominates Canadian Politics. Vancouver: UBC Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-7748-1195-8.

17. "Victim of media — Strong". The Ottawa Journal. February 13, 1979. p. 18. Retrieved December 1,2015.

18. Machan, Dyan (January 12, 1998). "Saving the Planet with Maurice Strong". Article. Retrieved April 1, 2016 – via Forbes website.

19. Stephen Gascoyne. "The Grit of a Colorado Water War Plan to Pump Water from the San Luis Valley Threatens Future of a National Monument". The Christian Science Monitor. Quetia, subscription required. Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

20. Colorado Supreme Court (May 9, 1994). "American Water Development Inc. v. City of Alamosa" (Court decision). Retrieved June 9, 2011.

21. "Rural area beats back water diversion plan" article by Barry Noreen, High Country News May 30, 1994

22. "District of Massachusetts Class Action Complaint No. 97". May 1, 1997. Retrieved April 1, 2016 – via University of Standford Education.

23. Leung, Shirley (January 22, 2014). "Molten Metal Revisited". Boston Globe. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

24. Ward, Barbara; Dubos, Rene. Only One Earth. May 25, 1972. Andre Deutsch ISBN 0233963081

25. http://www.unep.org Website of the United Nations Environment Programme

26. "A super agency?". Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2008-01-14.[dead link] Member account login required to access full article.

27. Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio, 1992

28. Tribute Special Supplement: On the Road to Rio. (1991). World Media Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

29. "Rio Organizer Says Summit Fell Short:" Environmental Principles Approved", article by Michael Weisskopf and Julia Preston in The Washington Post June 15, 1992, accessed September 8, 2010

30. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-12-19. Retrieved 2009-12-18.

31. "University of Peace Makes New Appointments and Agrees on Major Expansion". Science Blog. Retrieved 2008-01-05.

32. "UN urges North Korea-US talks". London: British Broadcasting Corporation. April 4, 2003. Retrieved 2008-01-05.

33. Kimitch, Rebecca (October 15, 2004). "University for Peace not Peaceful, Nor Transparent". Tico Times. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

34. Rosett, Claudia (October 11, 2008). "Maurice Strong: The U.N.'s Man of Mystery - WSJ.com". online.wsj.com. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

35. Rosett, Claudia (January 10, 2006). "Strong Implications". National Review. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

36. Hickman, Leo (June 23, 2010). "Maurice Strong on climate 'conspiracy', Bilberberg and population control". The Guardian. London. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

37. Russell, George (June 20, 2012). "EXCLUSIVE: Godfather of Global Green Thinking Steps Out of Shadows at Rio+20". Fox News. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

38. McLeod, Judi (September 1, 2003). "On the way to Parliament: Uncle Mo in Activist Mode". Canada Free Press. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

39. Izzard, John (December 2, 2015). "Maurice Strong, Climate Crook". Quadrant. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

40. http://abcnews.go.com/International/wir ... s-35463459

41. "The Honourable Maurice STRONG: Obituary". legacy.com.

42. "Memorial Service for the Honourable Maurice Strong"(Press release). Ottawa: Governor General of Canada. January 26, 2016. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

43. Cohen, Andrew (January 26, 2016). "Cohen: Maurice Strong was the Earth's Mr. Fix-It". The Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

44. "CPAC Special - Maurice F. Strong Memorial". cpac.ca. January 27, 2016.

45. "'A truly great citizen of Canada': Maurice Strong remembered in Ottawa". Canadian Press. January 28, 2016.

46. Foster, Peter (November 29, 2015). "The man who shaped the climate agenda in Paris, Maurice Strong, leaves a complicated legacy". The National Post. Toronto.

47. "Order of Canada: Maurice F. Strong". http://www.gg.ca.

48. http://www.gg.ca/honour.aspx?id=43398&t=6&ln=Strong

49. http://www.gg.ca/honour.aspx?id=104780&t=13&ln=Strong

50. Canada Gazette Part I, Vol. 132, No. 26 Archived2013-05-22 at the Wayback Machine

51. http://www8.nationalacademies.org/onpin ... D=12032003

52. "Environmental Sustainability with Maurice Strong".

53. http://www.ewire.com/display.cfm/Wire_ID/1307Archived 2006-11-10 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on December 27, 2007

54. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-09-27. Retrieved 2016-02-09. Retrieved on December 27, 2007

55. http://mea.gov.in/pressbriefing/2004/07 ... mRetrieved on December 27, 2007

56. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-01-06. Retrieved 2016-02-09. Retrieved on December 27, 2007

57. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-05-02. Retrieved 2016-02-09. Retrieved on December 27, 2007

58. http://www.lindberghfoundation.org/inde ... 5Retrieved on December 27, 2007

59. http://www.mauricestrong.net/index.php/ ... ainmenu-20 Retrieved on July 16, 2014

60. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-04-02. Retrieved 2016-02-09. Retrieved on December 27, 2007

61. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-08-05. Retrieved 2016-02-09. Retrieved on December 27, 2007

62. "Honorary Degree Citation - Maurice Frederick Strong | Concordia University Archives". archives.concordia.ca. Retrieved 2016-03-30.

63. http://www.rsc.ca/index.php?page_id=70& ... 1Retrieved on December 27, 2007

64. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-12-07. Retrieved 2016-02-09. Retrieved on December 27, 2007

65. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-08-02. Retrieved 2009-09-04. Retrieved on January 13, 2008

66. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-03-26. Retrieved 2016-02-09. Retrieved on January 13, 2008

External links

• "Maurice Strong". NNDB.

• "Maurice F. Strong Papers". Environmental Science and Public Policy Archives, Harvard College Library, Harvard University. 30 May 2003. Archived from the original on 2008-01-01. Retrieved 2007-12-31. - Papers, 1948-2000

• Official website of Maurice Strong

• University for Peace

• "The World Mourns One of its Greats: Maurice Strong Dies, His Legacy Lives On" UNEP news on his death[permanent dead link]