by Wikipedia

Accessed: 4/19/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Gestalt therapy is an existential/experiential form of psychotherapy that emphasizes personal responsibility, and that focuses upon the individual's experience in the present moment, the therapist–client relationship, the environmental and social contexts of a person's life, and the self-regulating adjustments people make as a result of their overall situation.

Gestalt therapy was developed by Fritz Perls, Laura Perls and Paul Goodman in the 1940s and 1950s, and was first described in the 1951 book Gestalt Therapy.

Overview

Edwin Nevis, co-founder of the Gestalt Institute of Cleveland, founder of the Gestalt International Study Center, and faculty member at the MIT Sloan School of Management, described Gestalt therapy as "a conceptual and methodological base from which helping professionals can craft their practice".[1] In the same volume, Joel Latner stated that Gestalt therapy is built upon two central ideas: that the most helpful focus of psychotherapy is the experiential present moment, and that everyone is caught in webs of relationships; thus, it is only possible to know ourselves against the background of our relationships to others.[2] The historical development of Gestalt therapy (described below) discloses the influences that generated these two ideas. Expanded, they support the four chief theoretical constructs (explained in the theory and practice section) that comprise Gestalt theory, and that guide the practice and application of Gestalt therapy.

Gestalt therapy was forged from various influences upon the lives of its founders during the times in which they lived, including: the new physics, Eastern religion, existential phenomenology, Gestalt psychology, psychoanalysis, experimental theatre, as well as systems theory and field theory.[3] Gestalt therapy rose from its beginnings in the middle of the 20th century to rapid and widespread popularity during the decade of the 1960s and early 1970s. During the '70s and '80s Gestalt therapy training centers spread globally; but they were, for the most part, not aligned with formal academic settings. As the cognitive revolution eclipsed Gestalt theory in psychology, many came to believe Gestalt was an anachronism. Because Gestalt therapists disdained the positivism underlying what they perceived to be the concern of research, they largely ignored the need to use research to further develop Gestalt theory and Gestalt therapy practice (with a few exceptions like Les Greenberg, see the interview: "Validating Gestalt"[4]). However, the new century has seen a sea of change in attitudes toward research and Gestalt practice.

Gestalt therapy is not identical with Gestalt psychology but Gestalt psychology influenced the development of Gestalt therapy to a large extent.[5]

Gestalt therapy focuses on process (what is actually happening) over content (what is being talked about).[6] The emphasis is on what is being done, thought, and felt at the present moment (the phenomenality of both client and therapist), rather than on what was, might be, could be, or should have been. Gestalt therapy is a method of awareness practice (also called "mindfulness" in other clinical domains), by which perceiving, feeling, and acting are understood to be conducive to interpreting, explaining, and conceptualizing (the hermeneutics of experience).[7] This distinction between direct experience versus indirect or secondary interpretation is developed in the process of therapy. The client learns to become aware of what he or she is doing and that triggers the ability to risk a shift or change.[8]

The objective of Gestalt therapy is to enable the client to become more fully and creatively alive and to become free from the blocks and unfinished business that may diminish satisfaction, fulfillment, and growth, and to experiment with new ways of being.[9] For this reason Gestalt therapy falls within the category of humanistic psychotherapies. As Gestalt therapy includes perception and the meaning-making processes by which experience forms, it can also be considered a cognitive approach. Also, because Gestalt therapy relies on the contact between therapist and client, and because a relationship can be considered to be contact over time, Gestalt therapy can be considered a relational or interpersonal approach. As it appreciates the larger picture which is the complex situation involving multiple influences in a complex situation, it can also be considered a multi-systemic approach. In addition, the processes of Gestalt therapy are experimental, involving action, Gestalt therapy can be considered both a paradoxical and an experiential/experimental approach.[7]

When Gestalt therapy is compared to other clinical domains, a person can find many matches, or points of similarity. "Probably the clearest case of consilience is between gestalt therapy's field perspective and the various organismic and field theories that proliferated in neuroscience, medicine, and physics in the early and mid-20th century. Within social science there is a consilience between gestalt field theory and systems or ecological psychotherapy; between the concept of dialogical relationship and object relations, attachment theory, client-centered therapy and the transference-oriented approaches; between the existential, phenomenological, and hermeneutical aspects of gestalt therapy and the constructivist aspects of cognitive therapy; and between gestalt therapy's commitment to awareness and the natural processes of healing and mindfulness, acceptance and Buddhist techniques adopted by cognitive behavioral therapy."[10]

Contemporary theory and practice

The theoretical foundations of Gestalt therapy essentially rests atop four "load-bearing walls": phenomenological method, dialogical relationship, field-theoretical strategies, and experimental freedom.[11] Although all these tenets were present in the early formulation and practice of Gestalt therapy, as described in Ego, Hunger and Aggression (Perls, 1947) and in Gestalt Therapy, Excitement and Growth in the Human Personality (Perls, Hefferline, & Goodman, 1951), the early development of Gestalt therapy theory emphasized personal experience and the experiential episodes understood as "safe emergencies" or experiments. Indeed, half of the Perls, Hefferline, and Goodman book consists of such experiments. Later, through the influence of such people as Erving and Miriam Polster, a second theoretical emphasis emerged: namely, contact between self and other, and ultimately the dialogical relationship between therapist and client.[12] Later still, field theory emerged as an emphasis.[13] At various times over the decades, since Gestalt therapy first emerged, one or more of these tenets and the associated constructs that go with them have captured the imagination of those who have continued developing the contemporary theory of Gestalt therapy. Since 1990 the literature focused upon Gestalt therapy has flourished, including the development of several professional Gestalt journals. Along the way, Gestalt therapy theory has also been applied in Organizational Development and coaching work. And, more recently, Gestalt methods have been combined with meditation practices into a unified program of human development called Gestalt Practice, which is used by some practitioners.

Phenomenological method

The goal of a phenomenological exploration is awareness.[14] This exploration works systematically to reduce the effects of bias through repeated observations and inquiry.[15]

The phenomenological method comprises three steps: (1) the rule of epoché, (2) the rule of description, and (3) the rule of horizontalization.[16] Applying the rule of epoché one sets aside one's initial biases and prejudices in order to suspend expectations and assumptions. Applying the rule of description, one occupies oneself with describing instead of explaining. Applying the rule of horizontalization one treats each item of description as having equal value or significance.

The rule of epoché sets aside any initial theories with regard to what is presented in the meeting between therapist and client. The rule of description implies immediate and specific observations, abstaining from interpretations or explanations, especially those formed from the application of a clinical theory superimposed over the circumstances of experience. The rule of horizontalization avoids any hierarchical assignment of importance such that the data of experience become prioritized and categorized as they are received. A Gestalt therapist using the phenomenological method might say something like, “I notice a slight tension at the corners of your mouth when I say that, and I see you shifting on the couch and folding your arms across your chest ... and now I see you rolling your eyes back”. Of course, the therapist may make a clinically relevant evaluation, but when applying the phenomenological method, temporarily suspends the need to express it.[17]

Dialogical relationship

To create the conditions under which a dialogic moment might occur, the therapist attends to his or her own presence, creates the space for the client to enter in and become present as well (called inclusion), and commits him or herself to the dialogic process, surrendering to what takes place, as opposed to attempting to control it.[15] With presence, the therapist judiciously “shows up” as a whole and authentic person, instead of assuming a role, false self or persona. The word 'judicious' used above refers to the therapist's taking into account the specific strengths, weaknesses and values of the client. The only 'good' client is a 'live' client, so driving a client away by injudicious exposure of intolerable [to this client] experience of the therapist is obviously counter-productive. For example, for an atheistic therapist to tell a devout client that religion is myth would not be useful, especially in the early stages of the relationship. To practice inclusion is to accept however the client chooses to be present, whether in a defensive and obnoxious stance or a superficially cooperative one. To practice inclusion is to support the presence of the client, including his or her resistance, not as a gimmick but in full realization that this is how the client is actually present and is the best this client can do at this time. Finally, the Gestalt therapist is committed to the process, trusts in that process, and does not attempt to save him or herself from it (Brownell, in press, 2009, 2008)).

Field-theoretical strategies

Field theory is a concept borrowed from physics in which people and events are no longer considered discrete units but as parts of something larger, which are influenced by everything including the past, and observation itself. “The field” can be considered in two ways. There are ontological dimensions and there are phenomenological dimensions to one's field. The ontological dimensions are all those physical and environmental contexts in which we live and move. They might be the office in which one works, the house in which one lives, the city and country of which one is a citizen, and so forth. The ontological field is the objective reality that supports our physical existence. The phenomenological dimensions are all mental and physical dynamics that contribute to a person's sense of self, one's subjective experience—not merely elements of the environmental context. These might be the memory of an uncle's inappropriate affection, one's color blindness, one's sense of the social matrix in operation at the office in which one works, and so forth. The way that Gestalt therapists choose to work with field dynamics makes what they do strategic.[18] Gestalt therapy focuses upon character structure; according to Gestalt theory, the character structure is dynamic rather than fixed in nature. To become aware of one's character structure, the focus is upon the phenomenological dimensions in the context of the ontological dimensions.

Experimental freedom

Gestalt therapy is distinct because it moves toward action, away from mere talk therapy, and for this reason is considered an experiential approach.[19] Through experiments, the therapist supports the client's direct experience of something new, instead of merely talking about the possibility of something new. Indeed, the entire therapeutic relationship may be considered experimental, because at one level it is a corrective, relational experience for many clients, and it is a "safe emergency" that is free to turn out however it will. An experiment can also be conceived as a teaching method that creates an experience in which a client might learn something as part of their growth.[20] Examples might include: (1) Rather than talking about the client's critical parent, a Gestalt therapist might ask the client to imagine the parent is present, or that the therapist is the parent, and talk to that parent directly; (2) If a client is struggling with how to be assertive, a Gestalt therapist could either (a) have the client say some assertive things to the therapist or members of a therapy group, or (b) give a talk about how one should never be assertive; (3) A Gestalt therapist might notice something about the non-verbal behavior or tone of voice of the client; then the therapist might have the client exaggerate the non-verbal behavior and pay attention to that experience; (4) A Gestalt therapist might work with the breathing or posture of the client, and direct awareness to changes that might happen when the client talks about different content. With all these experiments the Gestalt therapist is working with process rather than content, the How rather than the What.

Noteworthy issues

Self

In field theory, self is a phenomenological concept, existing in comparison with other. Without the other there is no self, and how one experiences the other is inseparable from how one experiences oneself. The continuity of selfhood (functioning personality) is something that is achieved in relationship, rather than something inherently "inside" the person. This can have its advantages and disadvantages. At one end of the spectrum, someone may not have enough self-continuity to be able to make meaningful relationships, or to have a workable sense of who she is. In the middle, her personality is a loose set of ways of being that work for her, including commitments to relationships, work, culture and outlook, always open to change where she needs to adapt to new circumstances or just want to try something new. At the other end, her personality is a rigid defensive denial of the new and spontaneous. She acts in stereotyped ways, and either induces other people to act in particular and fixed ways towards her, or she redefines their actions to fit with fixed stereotypes.

In Gestalt therapy, the process is not about the self of the client being helped or healed by the fixed self of the therapist; rather it is an exploration of the co-creation of self and other in the here-and-now of the therapy. There is no assumption that the client will act in all other circumstances as he or she does in the therapy situation. However, the areas that cause problems will be either the lack of self-definition leading to chaotic or psychotic behaviour, or the rigid self-definition in some area of functioning that denies spontaneity and makes dealing with particular situations impossible. Both of these conditions show up very clearly in the therapy, and can be worked with in the relationship with the therapist.

The experience of the therapist is also very much part of the therapy. Since we co-create our self-other experiences, the way a therapist experiences being with a client is significant information about how the client experiences themselves. The proviso here is that a therapist is not operating from their own fixed responses. This is why Gestalt therapists are required to undertake significant therapy of their own during training.

From the perspective of this theory of self, neurosis can be seen as fixed predictability—a fixed Gestalt—and the process of therapy can be seen as facilitating the client to become unpredictable: more responsive to what is in the client's present environment, rather than responding in a stuck way to past introjects or other learning. If the therapist has expectations of how the client should end up, this defeats the aim of therapy.

Change

In what has now become a "classic" of Gestalt therapy literature, Arnold R. Beisser described Gestalt's paradoxical theory of change.[21] The paradox is that the more one attempts to be who one is not, the more one remains the same. Conversely, when people identify with their current experience, the conditions of wholeness and growth support change. Put another way, change comes about as a result of "full acceptance of what is, rather than a striving to be different."[22]

The empty chair technique

Empty chair technique or chairwork is typically used in Gestalt therapy when a patient might have deep-rooted emotional problems from someone or something in their life, such as relationships with themselves, with aspects of their personality, their concepts, ideas, feelings, etc., or other people in their lives. The purpose of this technique is to get the patient to think about their emotions and attitudes.[23] Common things the patient addresses in the empty chair are another person, aspects of their own personality, a certain feeling, etc., as if that thing were in that chair.[24] They may also move between chairs and act out two or more sides of a discussion, typically involving the patient and persons significant to them. It uses a passive approach to opening up the patient's emotions and pent-up feelings so they can let go of what they have been holding back. A form of role-playing, the technique focuses on exploration of self and is used by therapists to help patients self-adjust. Gestalt techniques were originally a form of psychotherapy, but are now often used in counseling, for instance, by encouraging clients to act out their feelings helping them prepare for a new job.[25] The purpose of the technique is so the patient will become more in touch with their feelings and have an emotional conversation that clears up any long-held feelings or reaction to the person or object in the chair.[26] When used effectively, it provides an emotional release and lets the client move forward in their life.

Historical development

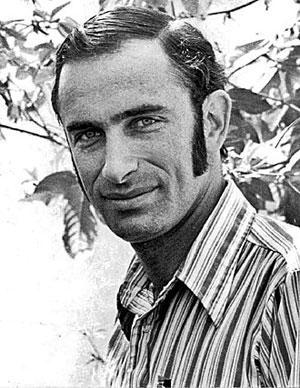

Fritz Perls was a German-Jewish psychoanalyst who fled Europe with his wife Laura Perls to South Africa in order to escape Nazi oppression in 1933.[27] After World War II, the couple emigrated to New York City, which had become a center of intellectual, artistic and political experimentation by the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Early influences

Perls grew up on the bohemian scene in Berlin, participated in Expressionism and Dadaism, and experienced the turning of the artistic avant-garde toward the revolutionary left. Deployment to the front line, the trauma of war, anti-Semitism, intimidation, escape, and the Holocaust are further key sources of biographical influence.[27]

Perls served in the German Army during World War I, and was wounded in the conflict. After the war he was educated as a medical doctor. He became an assistant to Kurt Goldstein, who worked with brain-injured soldiers. Perls went through a psychoanalysis with Wilhelm Reich and became a psychiatrist. Perls assisted Goldstein at Frankfurt University where he met his wife Lore (Laura) Posner, who had earned a doctorate in Gestalt psychology.[28] They fled Nazi Germany in 1933 and settled in South Africa. Perls established a psychoanalytic training institute and joined the South African armed forces, serving as a military psychiatrist. During these years in South Africa, Perls was influenced by Jan Smuts and his ideas about "holism".

In 1936 Fritz Perls attended a psychoanalysts' conference in Marienbad, Czechoslovakia, where he presented a paper on oral resistances, mainly based on Laura Perls's notes on breastfeeding their children. Perls's paper was turned down. Perls did present his paper in 1936, but it met with "deep disapproval."[29] Perls wrote his first book, Ego, Hunger and Aggression (1942, 1947), in South Africa, based in part on the rejected paper. It was later re-published in the United States. Laura Perls wrote two chapters of this book, but she was not given adequate recognition for her work.

The seminal book

Perls's seminal work was Gestalt Therapy: Excitement and Growth in the Human Personality, published in 1951, co-authored by Fritz Perls, Paul Goodman, and Ralph Hefferline (a university psychology professor and sometime patient of Fritz Perls). Most of Part II of the book was written by Paul Goodman from Perls's notes, and it contains the core of Gestalt theory. This part was supposed to appear first, but the publishers decided that Part I, written by Hefferline, fit into the nascent self-help ethos of the day, and they made it an introduction to the theory. Isadore From, a leading early theorist of Gestalt therapy, taught Goodman's Part II for an entire year to his students, going through it phrase by phrase.

First instances of Gestalt therapy

Fritz and Laura founded the first Gestalt Institute in 1952, running it out of their Manhattan apartment. Isadore From became a patient, first of Fritz, and then of Laura. Fritz soon made From a trainer, and also gave him some patients. From lived in New York until his death, at age seventy-five, in 1993. He was known worldwide for his philosophical and intellectually rigorous take on Gestalt therapy. Acknowledged as a supremely gifted clinician, he was indisposed to writing, so what remains of his work is merely transcripts of interviews.[30]

Of great importance to understanding the development of Gestalt therapy is the early training which took place in experiential groups in the Perls's apartment, led by both Fritz and Laura before Fritz left for the West Coast, and after by Laura alone. These "trainings" were unstructured, with little didactic input from the leaders, although many of the principles were discussed in the monthly meetings of the institute, as well as at local bars after the sessions. Many notable Gestalt therapists emerged from these crucibles in addition to Isadore From, e.g., Richard Kitzler, Dan Bloom, Bud Feder, Carl Hodges, and Ruth Ronall. In these sessions, both Fritz and Laura used some variation of the "hot seat" method, in which the leader essentially works with one individual in front of an audience with little or no attention to group dynamics. In reaction to this omission emerged a more interactive approach in which Gestalt-therapy principles were blended with group dynamics; in 1980, the book Beyond the Hot Seat, edited by Feder and Ronall, was published, with contributions from members of both the New York and Cleveland Institutes, as well as others.

Fritz left Laura and New York in 1960, briefly lived in Miami, and ended up in California. Jim Simkin was a psychotherapist who became a client of Perls in New York and then a co-therapist with Perls in Los Angeles. Simkin was responsible for Perls's going to California, where Perls began a psychotherapy practice. Ultimately, the life of a peripatetic trainer and workshop leader was better suited to Fritz's personality—starting in 1963, Simkin and Perls co-led some of the early Gestalt workshops and training groups at Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California, where Perls eventually settled and built a home. Jim Simkin then purchased property next to Esalen and started his own training center, which he ran until his death in 1984. Simkin refined his precise version of Gestalt therapy, training psychologists, psychiatrists, counselors and social workers within a very rigorous, residential training model.

The schism

In the 1960s, Perls became infamous among the professional elite for his public workshops at Esalen Institute. Isadore From referred to some of Fritz's brief workshops as "hit-and-run" therapy, because of Perls's alleged emphasis on showmanship with little or no follow-through—but Perls never considered these workshops to be complete therapy; rather, he felt he was giving demonstrations of key points for a largely professional audience. Unfortunately, some films and tapes of his work were all that most graduate students were exposed to, along with the misperception that these represented the entirety of Perls's work.

When Fritz Perls left New York for California, there began to be a split with those who saw Gestalt therapy as a therapeutic approach similar to psychoanalysis. This view was represented by Isadore From, who practiced and taught mainly in New York, as well as by the members of the Cleveland Institute, which was co-founded by From. An entirely different approach was taken, primarily in California, by those who saw Gestalt therapy not just as a therapeutic modality, but as a way of life. The East Coast, New York–Cleveland axis was often appalled by the notion of Gestalt therapy leaving the consulting room and becoming a way of life on the West Coast in the 1960s (see the "Gestalt prayer").

An alternative view of this split saw Perls in his last years continuing to develop his a-theoretical and phenomenological methodology, while others, inspired by From, were inclined to theoretical rigor which verged on replacing experience with ideas.

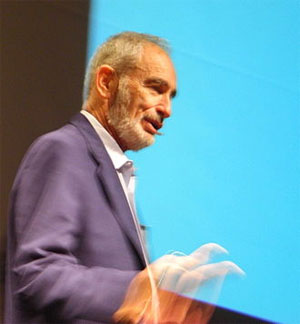

The split continues between what has been called "East Coast Gestalt" and "West Coast Gestalt," at least from an Amerocentric point of view. While the communitarian form of Gestalt continues to flourish, Gestalt therapy was largely replaced in the United States by Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, and many Gestalt therapists in the U.S. drifted toward organizational management and coaching. At the same time, contemporary Gestalt Practice (to a large extent based upon Gestalt therapy theory and practice) was developed by Dick Price, the co-founder of Esalen Institute.[31] Price was one of Perls's students at Esalen.

Post-Perls

In 1969, Fritz Perls left the United States to start a Gestalt community at Lake Cowichan on Vancouver Island, Canada. He died almost one year later, on 14 March 1970, in Chicago. One member of the Gestalt community was Barry Stevens. Her book about that phase of her life, Don't Push the River, became very popular. She developed her own form of Gestalt therapy body work, which is essentially a concentration on the awareness of body processes.[32]

The Polsters

Erving and Miriam Polster started a training center in La Jolla, California, which also became very well known, as did their book, Gestalt Therapy Integrated, in the 1970s.[33]

The Polsters played an influential role in advancing the concept of contact-boundary phenomena. The standard contact-boundary resistances in Gestalt theory were confluence, introjection, projection and retroflection. A disturbance described by Miriam and Erving Polster was deflection, which referred to a means of avoiding contact. Instances of boundary phenomena can have pathological or non-pathological aspects; for example, it is appropriate for an infant and mother to merge, or become "confluent," but inappropriate for a client and therapist to do so. If the latter do become confluent, there can be no growth, because there is no boundary at which one can contact the other: the client will not be able to learn anything new, because the therapist essentially becomes an extension of the client.

Influences upon Gestalt therapy

Some examples

There were a variety of psychological and philosophical influences upon the development of Gestalt therapy, not the least of which were the social forces at the time and place of its inception. Gestalt therapy is an approach that is holistic (including mind, body, and culture). It is present-centered and related to existential therapy in its emphasis on personal responsibility for action, and on the value of "I–thou" relationship in therapy. In fact, Perls considered calling Gestalt therapy existential-phenomenological therapy. "The I and thou in the Here and Now" was a semi-humorous shorthand mantra for Gestalt therapy, referring to the substantial influence of the work of Martin Buber—in particular his notion of the I–Thou relationship—on Perls and Gestalt. Buber's work emphasized immediacy, and required that any method or theory answer to the therapeutic situation, seen as a meeting between two people.[34] Any process or method that turns the patient into an object (the I–It) must be strictly secondary to the intimate, and spontaneous, I–Thou relation. This concept became important in much of Gestalt theory and practice.

Both Fritz and Laura Perls were students and admirers of the neuropsychiatrist Kurt Goldstein. Gestalt therapy was based in part on Goldstein's concept called Organismic theory. Goldstein viewed a person in terms of a holistic and unified experience; he encouraged a "big picture" perspective, taking into account the whole context of a person's experience. The word Gestalt means whole, or configuration. Laura Perls, in an interview, denotes the Organismic theory as the base of Gestalt therapy.[28]

There were additional influences on Gestalt therapy from existentialism, particularly the emphasis upon personal choice and responsibility.

The late 1950s–1960s movement toward personal growth and the human potential movement in California fed into, and was itself influenced by, Gestalt therapy. In this process Gestalt therapy somehow became a coherent Gestalt, which is the Gestalt psychology term for a perceptual unit that holds together and forms a unified whole.

Psychoanalysis

Fritz Perls trained as a neurologist at major medical institutions and as a Freudian psychoanalyst in Berlin and Vienna, the most important international centers of the discipline in his day. He worked as a training analyst for several years with the official recognition of the International Psychoanalytic Association (IPA), and must be considered an experienced clinician.[27] Gestalt therapy was influenced by psychoanalysis: it was part of a continuum moving from the early work of Freud, to the later Freudian ego analysis, to Wilhelm Reich and his character analysis and notion of character armor, with attention to nonverbal behavior; this was consonant with Laura Perls's background in dance and movement therapy. To this was added the insights of academic Gestalt psychology, including perception, Gestalt formation, and the tendency of organisms to complete an incomplete Gestalt and to form "wholes" in experience.

Central to Fritz and Laura Perls's modifications of psychoanalysis was the concept of dental or oral aggression. In Ego, Hunger and Aggression (1947), Fritz Perls's first book, to which Laura Perls contributed[35] (ultimately without recognition), Perls suggested that when the infant develops teeth, he or she has the capacity to chew, to break food apart, and, by analogy, to experience, taste, accept, reject, or assimilate. This was opposed to Freud's notion that only introjection takes place in early experience. Thus Perls made assimilation, as opposed to introjection, a focal theme in his work, and the prime means by which growth occurs in therapy.

In contrast to the psychoanalytic stance, in which the "patient" introjects the (presumably more healthy) interpretations of the analyst, in Gestalt therapy the client must "taste" his or her own experience and either accept or reject it—but not introject or "swallow whole." Hence, the emphasis is on avoiding interpretation, and instead encouraging discovery. This is the key point in the divergence of Gestalt therapy from traditional psychoanalysis: growth occurs through gradual assimilation of experience in a natural way, rather than by accepting the interpretations of the analyst; thus, the therapist should not interpret, but lead the client to discover for him- or herself.

The Gestalt therapist contrives experiments that lead the client to greater awareness and fuller experience of his or her possibilities. Experiments can be focused on undoing projections or retroflections. The therapist can work to help the client with closure of unfinished Gestalts ("unfinished business" such as unexpressed emotions towards somebody in the client's life). There are many kinds of experiments that might be therapeutic, but the essence of the work is that it is experiential rather than interpretive, and in this way, Gestalt therapy distinguishes itself from psychoanalysis.

Principal influences: a summary list

• Otto Rank's invention of "here-and-now" therapy and Rank's post-Freudian book Art and Artist (1932), both of which strongly influenced Paul Goodman.

• Wilhelm Reich's psychoanalytic developments, especially his early character analysis, and the later concept of character armor and its focus on the body.

• Jacob Moreno's psychodrama, principally the development of enactment techniques for the resolution of psychological conflicts.

• Kurt Goldstein's holistic theory of the organism, based on Gestalt theory.

• Martin Buber's philosophy of relationship and dialogue ("I–Thou").

• Kurt Lewin's field theory as applied to the social sciences and group dynamics.

• European phenomenology of Franz Brentano, Edmund Husserl, Martin Heidegger, and Maurice Merleau-Ponty.

• The existentialism of Kierkegaard over that of Sartre, rejecting nihilism.

• Carl Jung's psychology, particularly the polarities concept.

• Some elements from Zen Buddhism.

• Differentiation between thing and concept from Zen and the works of Alfred Korzybski.

• The American pragmatism of William James, George Herbert Mead, and John Dewey.

Current status

Gestalt therapy reached a zenith in the United States in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Since then, it has influenced other fields like organizational development, coaching, and teaching. Many of its contributions have become assimilated into other current schools of therapy. In recent years, it has seen a resurgence in popularity as an active, psychodynamic form of therapy which has also incorporated some elements of recent developments in attachment theory. There are, for example, four Gestalt training institutes in the New York City metropolitan area alone, not to mention dozens of others worldwide.

Gestalt therapy continues to thrive as a widespread form of psychotherapy, especially throughout Europe, where there are many practitioners and training institutions. Dan Rosenblatt led Gestalt therapy training groups and public workshops at the Tokyo Psychotherapy Academy for seven years. Stewart Kiritz continued in this role from 1997 to 2006.

The form of Gestalt Practice initially developed at Esalen Institute by Dick Price has spawned numerous offshoots.

Training of Gestalt therapists

Pedagogical approach

Many Gestalt therapy training organizations exist worldwide. Ansel Woldt asserted that Gestalt teaching and training are built upon the belief that people are, by nature, health-seeking. Thus, such commitments as authenticity, optimism, holism, health, and trust become important principles to consider when engaged in the activity of teaching and learning—especially Gestalt therapy theory and practice.[36]

Associations

The Association for the Advancement of Gestalt Therapy (AAGT) holds a biennial international conference in various locations—the first was in New Orleans, in 1995. Subsequent conferences have been held in San Francisco, Cleveland, New York, Dallas, St. Pete's Beach, Vancouver (British Columbia), Manchester (England), and Philadelphia. In addition, the AAGT holds regional conferences, and its regional network has spawned regional conferences in Amsterdam, the Southwest and the Southeast of the United States, England, and Australia. Its Research Task Force generates and nurtures active research projects and an international conference on research.[37]

The European Association for Gestalt Therapy (EAGT), founded in 1985 to gather European individual Gestalt therapists, training institutes, and national associations from more than twenty European nations.[38]

Gestalt Australia and New Zealand (GANZ) was formally established at the first "Down Under" Gestalt Therapy Conference held in Perth in September 1998.[39]

See also

• Topdog vs. underdog

• Violet Oaklander

References

1. Nevis, E. (2000) Introduction, in Gestalt therapy: Perspectives and Applications. Edwin Nevis (ed.). Cambridge, MA: Gestalt Press. p. 3.

2. Latner, J. (2000) The Theory of Gestalt Therapy, in Gestalt therapy: Perspectives and Applications, Edwin Nevis (ed.) Cambridge, MA: Gestalt Press.

3. Mackewn, J. (1997) Developing Gestalt Counselling. London, UK: Sage publications; Bowman, C. & Brownell, P. (2000) Prelude to Contemporary Gestalt Therapy. Gestalt!, vol. 4, no. 3, available at http://www.g-gej.org/4-3/prelude.html Archived 6 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine

4. Validating Gestalt. An Interview with Researcher, Writer, and Psychotherapist Leslie Greenberg by Leslie Grennberg and Philip Brownell; in: Gestalt!, 1/1997.[1] Archived 8 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine

5. Some Gestalt psychologists distanced themselves strongly from Gestalt therapy, like Henle, M. (1978): Gestalt psychology and Gestalt therapy, in: Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 14 (1), pg. 23-32. Henle, however, restricts herself explicitly to only three of Perls' books from 1969 and 1972, leaving out Perls' earlier work, and Gestalt therapy in general. See Barlow criticizing Henle: Allen R. Barlow: Gestalt Therapy and Gestalt Psychology. Gestalt – Antecedent Influence or Historical Accident, in: The Gestalt Journal, Volume IV, Number 2, Fall, 1981.

6. John Sommers-Flanagan; Rita Sommers-Flanagan (2012). Counseling and Psychotherapy Theories in Context and Practice: Skills, Strategies, and Techniques, 2nd edition. John Wiley & Sons. p. 199. ISBN 0470617934.

7. Brownell, P. (2010) Gestalt Therapy: A Guide to Contemporary Practice. New York, NY: Springer Publishing

8. Beisser, A. (1970) The Paradoxical Theory of Change. In J. Fagan & I. Shepherd (eds.) Gestalt Therapy Now: Theory, Techniques, and Applications, pp. 77-80. Palo Alto, CA: Science and Behavior Books

9. Joseph Zinker (1977). The Creative Process in Gestalt Therapy. New York, Vintage Books.

10. Brownell, P. (2010) Gestalt Therapy: A Guide to Contemporary Practice. New York, NY: Springer Publishing. p. 174.

11. Brownell, P., ed.(2008) Handbook for Theory, Research, and Practice in Gestalt Therapy, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

12. Polster, E. & Polster, M. (1973) Gestalt Therapy Integrated: Contours of theory and practice. New York, NY: Brunner-Mazel.

13. Wheeler, G. (1991) Gestalt : A new approach to contact and resistance. New York, NY: Gardner.

14. Yontef, G. (1993) Awareness, Dialogue, and Process, essays on Gestalt therapy. Highland, NY: The Gestalt Journal Press, Inc.

15. Yontef, G. (2005) Gestalt Therapy Theory of Change, in Gestalt Therapy, History, Theory, and Practice. Ansel Woldt & Sarah Toman (eds). London, UK: Sage Publications

16. Spinelli, E. (2005) The interpreted world, an introduction to phenomenological psychology, 2nd edition. London, UK: Sage Publications.

17. Brownell, P. (2009) Gestalt therapy in The Professional Counselor's Desk Reference, Mark A. Stebnicki, Ph.D. and Irmo Marini, Ph.D. (eds.), New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

18. Brownell, P. (2010) Gestalt Therapy: A Guide to Contemporary Practice, New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

19. Crocker, S. (1999) A well-lived life, essays in Gestalt therapy. Cambridge, MA: Gestalt Press.

20. Melnick, J., March Nevis, S. (2005) Gestalt Therapy Methodology in Gestalt Therapy, History, Theory, and Practice. Ansel Woldt & Sarah Toman (eds). London, UK: Sage Publications

21. Beisser, A. (1970) The paradoxical theory of change, in J.Fagan & I Shepherd (eds) Gestalt Therapy Now: Theory, Techniques, Applications. Palo Alto, CA: Science and Behavior Books.

22. Houston, G. (2003) Brief Gestalt Therapy. London, UK: Sage Publications.

23. gdh. "Chapter15 - page 21 of 108". http://www.psychologicalselfhelp.org.

24. Nichol, M. P. & Schwartz, R. C. (2008). Family Therapy: Concepts and Methods (8th ed.). New York: Pearson Education. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-205-54320-5.

25. Daniel L. Schacter; Daniel T. Gilbert; Daniel M. Wegner (2011). Psychology(2nd ed.). New York, NY: Worth Publishers. p. 602–603. ISBN 1429237198.

26. "Cool Intervention #9: The Empty Chair". Psychology Today.

27. Bernd Bocian (2010). Fritz Perls in Berlin 1893 - 1933. Expressionism - Psychoanalysis - Judaism. EHP Verlag Andreas Kohlhage, Bergisch Gladbach.

28. For Goldstein's influence on the theory and practice of Gestalt therapy see: Allen R. Barlow: Gestalt Therapy and Gestalt Psychology. Gestalt-antecedent influence or historical accident, The Gestalt Journal, Volume IV, Number 2, (Fall, 1981)

29. Perls, F., (1969) In and Out the Garbage Pail Lafayette, CA: Real People Press.

30. "Oral Link". http://www.gestalt.org.

31. "Esalen Founders - Esalen". http://www.esalen.org.

32. Stevens, B. (1970) Don't Push the River (It Flows by Itself), Lafaette, CA: Real People Press.

33. Gestalt therapy integrated : contours of theory and practice, by Erving Polster and Miriam Polster, New York : Vintage Books, 1974

34. Buber, Martin; Rogers, Carl Ransom; Anderson, Rob; Cissna, Kenneth N. (14 August 1997). "The Martin Buber - Carl Rogers Dialogue: A New Transcript With Commentary". SUNY Press – via Google Books.

35. "Oral Link". http://www.gestalt.org.

36. Woldt, A. (2005) Pre-text: Gestalt pedagogy: Creating the field for teaching and learning, in Ansel Woldt & Sarah Toman (eds), Gestalt Therapy, History, Theory, and Practice. London, UK: Sage Publications.

37. "AAGT – Association for the Advancement of Gestalt Therapy". http://www.aagt.org.

38. ... "EAGT European Association for Gestalt Therapy". http://www.eagt.org.

39. GANZ Gestalt Australia & New Zealand

Further reading

• Perls, F. (1969) Ego, Hunger, and Aggression: The Beginning of Gestalt Therapy. New York, NY: Random House. (originally published in 1942, and re-published in 1947)

• Perls, F. (1969) Gestalt Therapy Verbatim[permanent dead link]. Moab, UT: Real People Press.

• Perls, F. (1969) In and Out the Garbage Pail. Lafayette, CA: Real People Press.

• Perls, F., Hefferline, R., & Goodman, P. (1951) Gestalt Therapy: Excitement and growth in the human personality. New York, NY: Julian.

• Perls, F. (1973) The Gestalt Approach & Eye Witness to Therapy. New York, NY: Bantam Books.

• Brownell, P. (2012) Gestalt Therapy for Addictive and Self-Medicating Behaviors. New York, NY: Springer Publishing.

• Levine, T.B-Y. (2011) Gestalt Therapy: Advances in Theory and Practice. New York, NY: Routledge.

• Bloom, D. & Brownell, P. (eds)(2011) Continuity and Change: Gestalt Therapy Now. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing

• Mann, D. (2010) Gestalt Therapy: 100 Key Points & Techniques. London & New York: Routledge.

• Bocian, B. (2010): "Fritz Perls in Berlin 1893 - 1933. Expressionism - Psychonalysis - Judaism". Bergisch Gladbach: EHP Verlag Andreas Kohlhage. ISBN 978-3-89797-068-7

• Brownell, P. (2010) Gestalt Therapy: A Guide to Contemporary Practice. New York, NY, US: Springer Publishing

• Truscott, D. (2010) Gestalt therapy. In Derek Truscott, Becoming An Effective Psychotherapist: Adopting a Theory of Psychotherapy That's Right for You and Your Client, pp. 83–96. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association.

• Brownell, P. (2009) Gestalt therapy. In Irmo Marini and Mark Stebnicki (eds) The Professional Counselor's Desk Reference, pp. 399–407. New York, NY, US: Springer Publishing Co.

• Staemmler, F-M. (2009) Aggression, Time, and Understanding: Contributions to the Evolution of Gestalt Therapy. New York, NY, US: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; GestaltPress Book

• Brownell, P. (ed.) (2008) Handbook for Theory, Research, and Practice in Gestalt Therapy. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing

• Polster, E. & Polster, M. (1973) Gestalt Therapy Integrated: Contours of theory and practice. New York, NY: Brunner-Mazel.

• Shorkey, C. & Uebel, M. (2008). Gestalt Therapy. In Terry Mizrahi and Larry Davis (eds) Encyclopedia of Social Work, 20th Edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

• Woldt, A. & Toman, S. (2005) "Gestalt Therapy: History, Theory and Practice." Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

• Bretz, HJ. (1994) "A Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Gestalt Therapy" {Pub Med}

• Yontef, Gary (1993). Awareness, Dialogue, and Process (pbk. ed.). The Gestalt Journal Press. ISBN 0939266202.

• Crocker, Sylvia Fleming (1999). A Well-Lived Life, Essays in Gestalt Therapy (pbk. ed.). SAGE Publications. ISBN 0881632872.

• Toman, Sarah; Woldt, Ansel, eds. (2005). Gestalt Therapy History, Theory, and Practice (pbk. ed.). Gestalt Press. ISBN 0761927913.

External links

• Resources in your library

• Resources in other libraries

• Gestalt therapy at Curlie