Re: Freda Bedi, by Wikipedia

Part 1 of 2

H. G. Wells

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 7/4/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

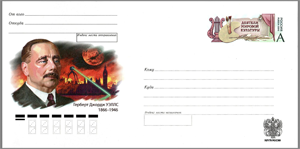

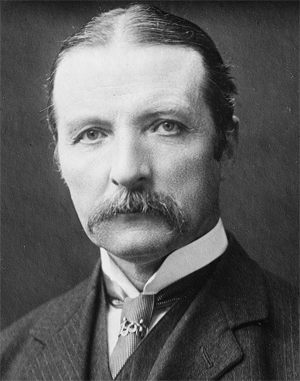

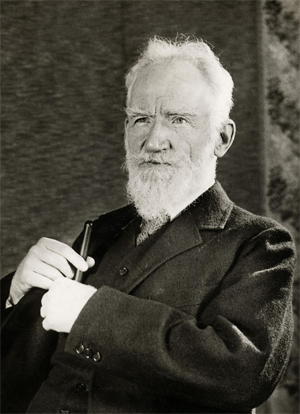

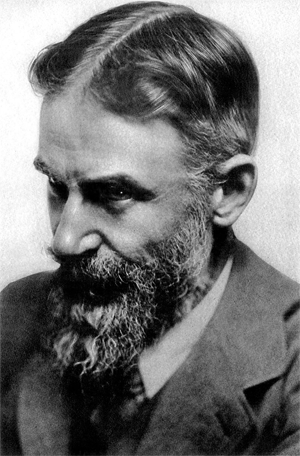

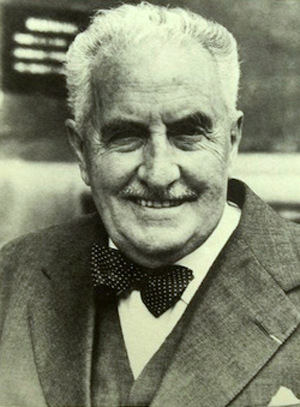

H. G. Wells

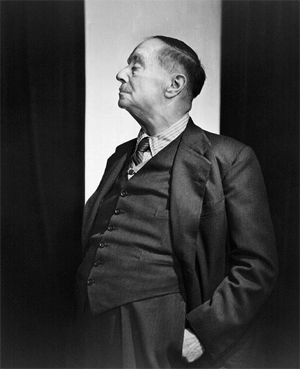

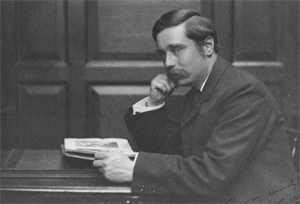

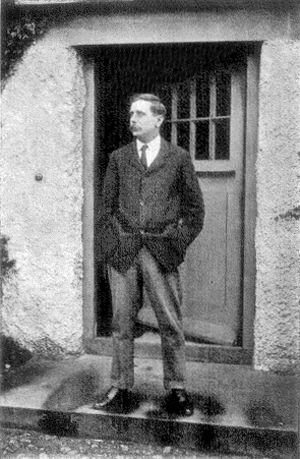

Photograph by George Charles Beresford, 1920

Born Herbert George Wells

21 September 1866

Bromley, Kent, England

Died 13 August 1946 (aged 79)

Regent's Park, London, England

Occupation Novelist, teacher, historian, journalist

Alma mater Royal College of Science (Imperial College London)

Genre Science fiction (notably social science fiction), social realism

Subject World history, progress

Notable works

The Outline of History

The Country of the Blind

The Red Room

Fiction:

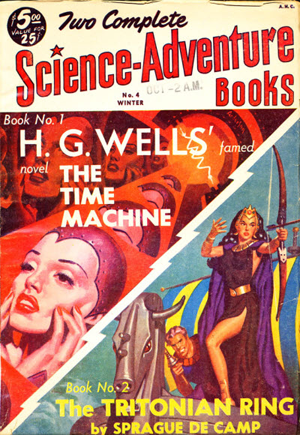

The Time Machine

The Invisible Man

The War of the Worlds

The Island of Doctor Moreau

The First Men in the Moon

The Shape of Things to Come

When the Sleeper Wakes

Years active 1895–1946

Spouse Isabel Mary Wells

(1891–1894, divorced)

Amy Catherine Robbins (1895–1927, her death)

Children George Phillip "G. P." Wells (1901–1985)

Frank Richard Wells (1903–1982)

Anna-Jane Kennard (1909–2010[1][2])

Anthony West (1914–1987)

Relatives Joseph Wells (father)

Sarah Neal (mother)

Herbert George Wells[3][4] (21 September 1866 – 13 August 1946) was an English writer. He was prolific in many genres, writing dozens of novels, short stories, and works of social commentary, satire, biography, and autobiography, and even including two books on recreational war games. He is now best remembered for his science fiction novels and is often called a "father of science fiction", along with Jules Verne and Hugo Gernsback.[5][6][a]

During his own lifetime, however, he was most prominent as a forward-looking, even prophetic social critic who devoted his literary talents to the development of a progressive vision on a global scale. A futurist, he wrote a number of utopian works and foresaw the advent of aircraft, tanks, space travel, nuclear weapons, satellite television and something resembling the World Wide Web.[7] His science fiction imagined time travel, alien invasion, invisibility, and biological engineering. Brian Aldiss referred to Wells as the "Shakespeare of science fiction".[8] Wells rendered his works convincing by instilling commonplace detail alongside a single extraordinary assumption – dubbed “Wells’s law” – leading Joseph Conrad to hail him in 1898 as "O Realist of the Fantastic!".[9] His most notable science fiction works include The Time Machine (1895), The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897), The War of the Worlds (1898) and the military science fiction The War in the Air (1907). Wells was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature four times.[10]

Wells's earliest specialised training was in biology, and his thinking on ethical matters took place in a specifically and fundamentally Darwinian context.[11] He was also from an early date an outspoken socialist, often (but not always, as at the beginning of the First World War) sympathising with pacifist views. His later works became increasingly political and didactic, and he wrote little science fiction, while he sometimes indicated on official documents that his profession was that of journalist.[12] Novels such as Kipps and The History of Mr Polly, which describe lower-middle-class life, led to the suggestion that he was a worthy successor to Charles Dickens,[13] but Wells described a range of social strata and even attempted, in Tono-Bungay (1909), a diagnosis of English society as a whole. Wells was a diabetic and co-founded the charity The Diabetic Association (known today as Diabetes UK) in 1934.[14]

Life

Early life

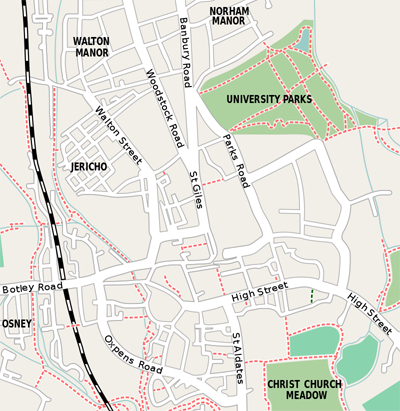

Herbert George Wells was born at Atlas House, 162 High Street in Bromley, Kent,[15] on 21 September 1866.[4] Called "Bertie" in the family, he was the fourth and last child of Joseph Wells (a former domestic gardener, and at the time a shopkeeper and professional cricketer) and his wife, Sarah Neal (a former domestic servant). An inheritance had allowed the family to acquire a shop in which they sold china and sporting goods, although it failed to prosper: the stock was old and worn out, and the location was poor. Joseph Wells managed to earn a meagre income, but little of it came from the shop and he received an unsteady amount of money from playing professional cricket for the Kent county team.[16] Payment for skilled bowlers and batsmen came from voluntary donations afterwards, or from small payments from the clubs where matches were played.

A defining incident of young Wells's life was an accident in 1874 that left him bedridden with a broken leg.[4] To pass the time he began to read books from the local library, brought to him by his father. He soon became devoted to the other worlds and lives to which books gave him access; they also stimulated his desire to write. Later that year he entered Thomas Morley's Commercial Academy, a private school founded in 1849, following the bankruptcy of Morley's earlier school. The teaching was erratic, the curriculum mostly focused, Wells later said, on producing copperplate handwriting and doing the sort of sums useful to tradesmen. Wells continued at Morley's Academy until 1880. In 1877, his father, Joseph Wells, suffered a fractured thigh. The accident effectively put an end to Joseph's career as a cricketer, and his subsequent earnings as a shopkeeper were not enough to compensate for the loss of the primary source of family income.[17]

Wells spent the winter of 1887-88 convalescing at Uppark, where his mother, Sarah, was housekeeper.[18]

No longer able to support themselves financially, the family instead sought to place their sons as apprentices in various occupations.[19] From 1880 to 1883, Wells had an unhappy apprenticeship as a draper at the Southsea Drapery Emporium, Hyde's.[20] His experiences at Hyde's, where he worked a thirteen-hour day and slept in a dormitory with other apprentices,[15] later inspired his novels The Wheels of Chance, The History of Mr Polly, and Kipps, which portray the life of a draper's apprentice as well as providing a critique of society's distribution of wealth.[21]

Wells's parents had a turbulent marriage, owing primarily to his mother's being a Protestant and his father's being a freethinker. When his mother returned to work as a lady's maid (at Uppark, a country house in Sussex), one of the conditions of work was that she would not be permitted to have living space for her husband and children. Thereafter, she and Joseph lived separate lives, though they never divorced and remained faithful to each other. As a consequence, Herbert's personal troubles increased as he subsequently failed as a draper and also, later, as a chemist's assistant. However, Uppark had a magnificent library in which he immersed himself, reading many classic works, including Plato's Republic, Thomas More's Utopia, and the works of Daniel Defoe.[22] This would be the beginning of Wells's venture into literature.

Teacher

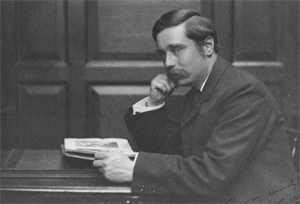

Wells studying in London c. 1890

In October 1879, Wells's mother arranged through a distant relative, Arthur Williams, for him to join the National School at Wookey in Somerset as a pupil–teacher, a senior pupil who acted as a teacher of younger children.[20] In December that year, however, Williams was dismissed for irregularities in his qualifications and Wells was returned to Uppark. After a short apprenticeship at a chemist in nearby Midhurst and an even shorter stay as a boarder at Midhurst Grammar School, he signed his apprenticeship papers at Hyde's. In 1883, Wells persuaded his parents to release him from the apprenticeship, taking an opportunity offered by Midhurst Grammar School again to become a pupil–teacher; his proficiency in Latin and science during his earlier short stay had been remembered.[16][20]

The years he spent in Southsea had been the most miserable of his life to that point, but his good fortune at securing a position at Midhurst Grammar School meant that Wells could continue his self-education in earnest.[16] The following year, Wells won a scholarship to the Normal School of Science (later the Royal College of Science in South Kensington, now part of Imperial College London) in London, studying biology under Thomas Henry Huxley.[23] As an alumnus, he later helped to set up the Royal College of Science Association, of which he became the first president in 1909. Wells studied in his new school until 1887, with a weekly allowance of 21 shillings (a guinea) thanks to his scholarship. This ought to have been a comfortable sum of money (at the time many working class families had "round about a pound a week" as their entire household income)[24] yet in his Experiment in Autobiography, Wells speaks of constantly being hungry, and indeed photographs of him at the time show a youth who is very thin and malnourished.[25]

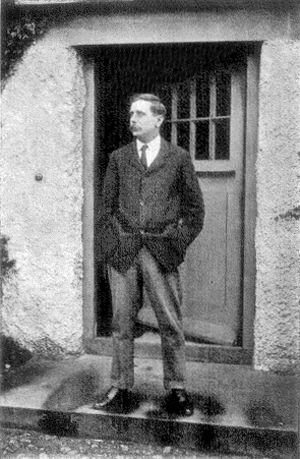

H. G. Wells in 1907 at the door of his house at Sandgate

He soon entered the Debating Society of the school. These years mark the beginning of his interest in a possible reformation of society. At first approaching the subject through Plato's Republic, he soon turned to contemporary ideas of socialism as expressed by the recently formed Fabian Society and free lectures delivered at Kelmscott House, the home of William Morris. He was also among the founders of The Science School Journal, a school magazine that allowed him to express his views on literature and society, as well as trying his hand at fiction; a precursor to his novel The Time Machine was published in the journal under the title The Chronic Argonauts. The school year 1886–87 was the last year of his studies.[23]

During 1888, Wells stayed in Stoke-on-Trent, living in Basford. The unique environment of The Potteries was certainly an inspiration. He wrote in a letter to a friend from the area that "the district made an immense impression on me." The inspiration for some of his descriptions in The War of the Worlds is thought to have come from his short time spent here, seeing the iron foundry furnaces burn over the city, shooting huge red light into the skies. His stay in The Potteries also resulted in the macabre short story "The Cone" (1895, contemporaneous with his famous The Time Machine), set in the north of the city.[26]

After teaching for some time, he was briefly on the staff of Holt Academy in Wales[27] – Wells found it necessary to supplement his knowledge relating to educational principles and methodology and entered the College of Preceptors (College of Teachers). He later received his Licentiate and Fellowship FCP diplomas from the College. It was not until 1890 that Wells earned a Bachelor of Science degree in zoology from the University of London External Programme. In 1889–90, he managed to find a post as a teacher at Henley House School in London, where he taught A. A. Milne (whose father ran the school).[28][29] His first published work was a Text-Book of Biology in two volumes (1893).[30]

Upon leaving the Normal School of Science, Wells was left without a source of income. His aunt Mary—his father's sister-in-law—invited him to stay with her for a while, which solved his immediate problem of accommodation. During his stay at his aunt's residence, he grew increasingly interested in her daughter, Isabel. He would later go on to court her. To earn money, he began writing short humorous articles for journals such as The Pall Mall Gazette, later collecting these in volume form as Select Conversations with an Uncle (1895) and Certain Personal Matters (1897). So prolific did Wells become at this mode of journalism that many of his early pieces remain unidentified. According to David C Smith, "Most of Wells's occasional pieces have not been collected, and many have not even been identified as his. Wells did not automatically receive the byline his reputation demanded until after 1896 or so ... As a result, many of his early pieces are unknown. It is obvious that many early Wells items have been lost."[31] His success with these shorter pieces encouraged him to write book-length work, and he published his first novel, The Time Machine, in 1895.[32]

Personal life

141 Maybury Rd, Woking, where Wells lived from May 1895 until late 1896[33]

In 1891, Wells married his cousin Isabel Mary Wells (1865–1931; from 1902 Isabel Mary Smith). The couple agreed to separate in 1894, when he had fallen in love with one of his students, Amy Catherine Robbins (1872–1927; later known as Jane), with whom he moved to Woking, Surrey in May 1895. They lived in a rented house, 'Lynton', (now No.141) Maybury Road in the town centre for just under 18 months[34] and married at St Pancras register office in October 1895.[35] His short period in Woking was perhaps the most creative and productive of his whole writing career,[34] for while there he planned and wrote The War of the Worlds and The Time Machine, completed The Island of Doctor Moreau, wrote and published The Wonderful Visit and The Wheels of Chance, and began writing two other early books, When the Sleeper Wakes and Love and Mr Lewisham.[34][36]

In late summer 1896, Wells and Jane moved to a larger house in Worcester Park, near Kingston upon Thames, for two years; this lasted until his poor health took them to Sandgate, near Folkestone, where he constructed a large family home, Spade House, in 1901. He had two sons with Jane: George Philip (known as "Gip"; 1901–1985) and Frank Richard (1903–1982).[37] Jane died 6 October 1927, in Dunmow, at the age of 55.

Wells had affairs with a significant number of women.[38] In December 1909, he had a daughter, Anna-Jane, with the writer Amber Reeves,[39] whose parents, William and Maud Pember Reeves, he had met through the Fabian Society. Amber had married the barrister G. R. Blanco White in July of that year, as co-arranged by Wells. After Beatrice Webb voiced disapproval of Wells' "sordid intrigue" with Amber, he responded by lampooning Beatrice Webb and her husband Sidney Webb in his 1911 novel The New Machiavelli as 'Altiora and Oscar Bailey', a pair of short-sighted, bourgeois manipulators. Between 1910–1913, novelist Elizabeth von Arnim was one of his mistresses.[40] In 1914, he had a son, Anthony West (1914–1987), by the novelist and feminist Rebecca West, 26 years his junior.[41] In 1920–21, and intermittently until his death, he had a love affair with the American birth control activist Margaret Sanger.[42] Between 1924 and 1933 he partnered with the 22-year younger Dutch adventurer and writer Odette Keun, with whom he lived in Lou Pidou, a house they built together in Grasse, France. Wells dedicated his longest book to her (The World of William Clissold, 1926).[43] When visiting Maxim Gorky in Russia 1920, he had slept with Gorky's mistress Moura Budberg, then still Countess Benckendorf and 27 years his junior. In 1933, when she left Gorky and emigrated to London, their relationship renewed and she cared for him through his final illness. Wells asked her to marry him repeatedly, but Budberg strongly rejected his proposals.[44][45]

In Experiment in Autobiography (1934), Wells wrote: "I was never a great amorist, though I have loved several people very deeply".[46] David Lodge's novel A Man of Parts (2011)—a 'narrative based on factual sources' (author's note)—gives a convincing and generally sympathetic account of Wells's relations with the women mentioned above, and others.[47]

Director Simon Wells (born 1961), the author's great-grandson, was a consultant on the future scenes in Back to the Future Part II (1989).[48]

Artist

One of the ways that Wells expressed himself was through his drawings and sketches. One common location for these was the endpapers and title pages of his own diaries, and they covered a wide variety of topics, from political commentary to his feelings toward his literary contemporaries and his current romantic interests. During his marriage to Amy Catherine, whom he nicknamed Jane, he drew a considerable number of pictures, many of them being overt comments on their marriage. During this period, he called these pictures "picshuas".[49] These picshuas have been the topic of study by Wells scholars for many years, and in 2006, a book was published on the subject.[50]

Writer

Statue of a tripod from The War of the Worlds in Woking, England. The book is a seminal depiction of a conflict between mankind and an extraterrestrial race.

Some of his early novels, called "scientific romances", invented several themes now classic in science fiction in such works as The Time Machine, The Island of Doctor Moreau, The Invisible Man, The War of the Worlds, When the Sleeper Wakes, and The First Men in the Moon. He also wrote realistic novels that received critical acclaim, including Kipps and a critique of English culture during the Edwardian period, Tono-Bungay. Wells also wrote dozens of short stories and novellas, including, "The Flowering of the Strange Orchid", which helped bring the full impact of Darwin's revolutionary botanical ideas to a wider public, and was followed by many later successes such as "The Country of the Blind" (1904).[51]

According to James Gunn, one of Wells's major contributions to the science fiction genre was his approach, which he referred to as his "new system of ideas".[52] In his opinion, the author should always strive to make the story as credible as possible, even if both the writer and the reader knew certain elements are impossible, allowing the reader to accept the ideas as something that could really happen, today referred to as "the plausible impossible" and "suspension of disbelief". While neither invisibility nor time travel was new in speculative fiction, Wells added a sense of realism to the concepts which the readers were not familiar with. He conceived the idea of using a vehicle that allows an operator to travel purposely and selectively forwards or backwards in time. The term "time machine", coined by Wells, is now almost universally used to refer to such a vehicle.[22] He explained that while writing The Time Machine, he realized that "the more impossible the story I had to tell, the more ordinary must be the setting, and the circumstances in which I now set the Time Traveller were all that I could imagine of solid upper-class comforts."[53] In "Wells's Law", a science fiction story should contain only a single extraordinary assumption. Being aware the notion of magic as something real had disappeared from society, he, therefore, used scientific ideas and theories as a substitute for magic to justify the impossible. Wells's best-known statement of the "law" appears in his introduction to The Scientific Romances of H. G. Wells (1933),

Dr. Griffin / The Invisible Man is a brilliant research scientist who discovers a method of invisibility, but finds himself unable to reverse the process. An enthusiast of random and irresponsible violence, Griffin has become an iconic character in horror fiction.[55] The Island of Doctor Moreau sees a shipwrecked man left on the island home of Doctor Moreau, a mad scientist who creates human-like hybrid beings from animals via vivisection.[56] The earliest depiction of uplift, the novel deals with a number of philosophical themes, including pain and cruelty, moral responsibility, human identity, and human interference with nature.[57] Though Tono-Bungay is not a science-fiction novel, radioactive decay plays a small but consequential role in it. Radioactive decay plays a much larger role in The World Set Free (1914). This book contains what is surely his biggest prophetic "hit", with the first description of a nuclear weapon.[58] Scientists of the day were well aware that the natural decay of radium releases energy at a slow rate over thousands of years. The rate of release is too slow to have practical utility, but the total amount released is huge. Wells's novel revolves around an (unspecified) invention that accelerates the process of radioactive decay, producing bombs that explode with no more than the force of ordinary high explosives—but which "continue to explode" for days on end. "Nothing could have been more obvious to the people of the earlier twentieth century", he wrote, "than the rapidity with which war was becoming impossible ... [but] they did not see it until the atomic bombs burst in their fumbling hands".[58] In 1932, the physicist and conceiver of nuclear chain reaction Leó Szilárd read The World Set Free (the same year Sir James Chadwick discovered the neutron), a book which he said made a great impression on him.[59]

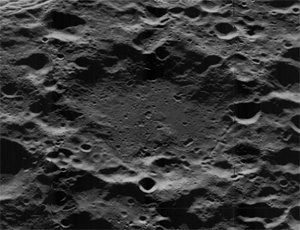

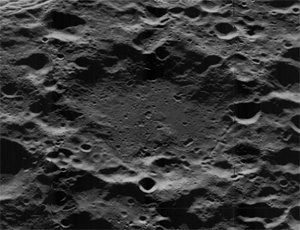

The H. G. Wells crater, located on the far side of the Moon, was named after the author of The First Men in the Moon (1901) in 1970.

Wells also wrote non-fiction. His first non-fiction bestseller was Anticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress upon Human Life and Thought (1901). When originally serialised in a magazine it was subtitled "An Experiment in Prophecy", and is considered his most explicitly futuristic work. It offered the immediate political message of the privileged sections of society continuing to bar capable men from other classes from advancement until war would force a need to employ those most able, rather than the traditional upper classes, as leaders. Anticipating what the world would be like in the year 2000, the book is interesting both for its hits (trains and cars resulting in the dispersion of populations from cities to suburbs; moral restrictions declining as men and women seek greater sexual freedom; the defeat of German militarism, and the existence of a European Union) and its misses (he did not expect successful aircraft before 1950, and averred that "my imagination refuses to see any sort of submarine doing anything but suffocate its crew and founder at sea").[60][61]

His bestselling two-volume work, The Outline of History (1920), began a new era of popularised world history. It received a mixed critical response from professional historians.[62] However, it was very popular amongst the general population and made Wells a rich man. Many other authors followed with "Outlines" of their own in other subjects. He reprised his Outline in 1922 with a much shorter popular work, A Short History of the World, a history book praised by Albert Einstein,[63] and two long efforts, The Science of Life (1930) and The Work, Wealth and Happiness of Mankind (1931).[64][65] The "Outlines" became sufficiently common for James Thurber to parody the trend in his humorous essay, "An Outline of Scientists"—indeed, Wells's Outline of History remains in print with a new 2005 edition, while A Short History of the World has been re-edited (2006).[66]

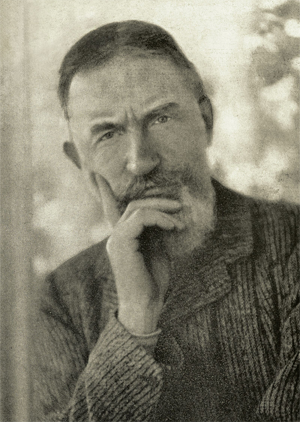

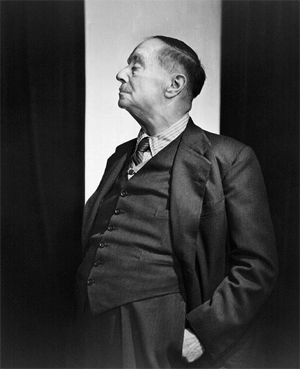

H. G. Wells c. 1918

From quite early in Wells's career, he sought a better way to organise society and wrote a number of Utopian novels. The first of these was A Modern Utopia (1905), which shows a worldwide utopia with "no imports but meteorites, and no exports at all";[67] two travellers from our world fall into its alternate history. The others usually begin with the world rushing to catastrophe, until people realise a better way of living: whether by mysterious gases from a comet causing people to behave rationally and abandoning a European war (In the Days of the Comet (1906)), or a world council of scientists taking over, as in The Shape of Things to Come (1933, which he later adapted for the 1936 Alexander Korda film, Things to Come). This depicted, all too accurately, the impending World War, with cities being destroyed by aerial bombs. He also portrayed the rise of fascist dictators in The Autocracy of Mr Parham (1930) and The Holy Terror (1939). Men Like Gods (1923) is also a utopian novel. Wells in this period was regarded as an enormously influential figure; the critic Malcolm Cowley stated: "by the time he was forty, his influence was wider than any other living English writer".[68]

Wells contemplates the ideas of nature and nurture and questions humanity in books such as The Island of Doctor Moreau. Not all his scientific romances ended in a Utopia, and Wells also wrote a dystopian novel, When the Sleeper Wakes (1899, rewritten as The Sleeper Awakes, 1910), which pictures a future society where the classes have become more and more separated, leading to a revolt of the masses against the rulers.[69] The Island of Doctor Moreau is even darker. The narrator, having been trapped on an island of animals vivisected (unsuccessfully) into human beings, eventually returns to England; like Gulliver on his return from the Houyhnhnms, he finds himself unable to shake off the perceptions of his fellow humans as barely civilised beasts, slowly reverting to their animal natures.[70]

Wells also wrote the preface for the first edition of W. N. P. Barbellion's diaries, The Journal of a Disappointed Man, published in 1919. Since "Barbellion" was the real author's pen name, many reviewers believed Wells to have been the true author of the Journal; Wells always denied this, despite being full of praise for the diaries.[71]

H. G. Wells, one day before his 60th birthday, on the front cover of Time magazine, 20 September 1926

In 1927, a Canadian teacher and writer Florence Deeks unsuccessfully sued Wells for infringement of copyright and breach of trust, claiming that much of The Outline of History had been plagiarised from her unpublished manuscript,[72] The Web of the World's Romance, which had spent nearly nine months in the hands of Wells's Canadian publisher, Macmillan Canada.[73] However, it was sworn on oath at the trial that the manuscript remained in Toronto in the safekeeping of Macmillan, and that Wells did not even know it existed, let alone had seen it.[74] The court found no proof of copying, and decided the similarities were due to the fact that the books had similar nature and both writers had access to the same sources.[75] In 2000, A. B. McKillop, a professor of history at Carleton University, produced a book on the case, The Spinster & The Prophet: Florence Deeks, H. G. Wells, and the Mystery of the Purloined Past.[76] According to McKillop, the lawsuit was unsuccessful due to the prejudice against a woman suing a well-known and famous male author, and he paints a detailed story based on the circumstantial evidence of the case.[77] In 2004, Denis N. Magnusson, Professor Emeritus of the Faculty of Law, Queen's University, Ontario, published an article on Deeks v. Wells. This re-examines the case in relation to McKillop's book. While having some sympathy for Deeks, he argues that she had a weak case that was not well presented, and though she may have met with sexism from her lawyers, she received a fair trial, adding that the law applied is essentially the same law that would be applied to a similar case today (i.e., 2004).[78]

In 1933, Wells predicted in The Shape of Things to Come that the world war he feared would begin in January 1940,[79] a prediction which ultimately came true four months early, in September 1939, with the outbreak of World War II.[80] In 1936, before the Royal Institution, Wells called for the compilation of a constantly growing and changing World Encyclopaedia, to be reviewed by outstanding authorities and made accessible to every human being. In 1938, he published a collection of essays on the future organisation of knowledge and education, World Brain, including the essay "The Idea of a Permanent World Encyclopaedia".[81]

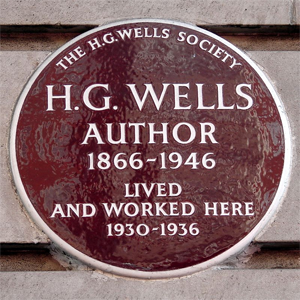

Plaque by the H. G. Wells Society at Chiltern Court, Baker Street in the City of Westminster, London, where Wells lived between 1930 and 1936

Prior to 1933, Wells's books were widely read in Germany and Austria, and most of his science fiction works had been translated shortly after publication.[82] By 1933, he had attracted the attention of German officials because of his criticism of the political situation in Germany, and on 10 May 1933, Wells's books were burned by the Nazi youth in Berlin's Opernplatz, and his works were banned from libraries and book stores.[82] Wells, as president of PEN International (Poets, Essayists, Novelists), angered the Nazis by overseeing the expulsion of the German PEN club from the international body in 1934 following the German PEN's refusal to admit non-Aryan writers to its membership. At a PEN conference in Ragusa, Wells refused to yield to Nazi sympathisers who demanded that the exiled author Ernst Toller be prevented from speaking.[82] Near the end of the World War II, Allied forces discovered that the SS had compiled lists of people slated for immediate arrest during the invasion of Britain in the abandoned Operation Sea Lion, with Wells included in the alphabetical list of "The Black Book".[83]

Seeking a more structured way to play war games, Wells also wrote Floor Games (1911) followed by Little Wars (1913), which set out rules for fighting battles with toy soldiers (miniatures).[84] Little Wars is recognised today as the first recreational war game and Wells is regarded by gamers and hobbyists as "the Father of Miniature War Gaming".[85] A pacifist prior to the First World War, Wells stated "how much better is this amiable miniature [war] than the real thing".[84] According to Wells, the idea of the miniature war game developed from a visit by his friend Jerome K. Jerome. After dinner, Jerome began shooting down toy soldiers with a toy cannon and Wells joined in to compete.[84]

Travels to Russia

Wells visited Russia three times: 1914, 1920 and 1934. During his second visit, he saw his old friend Maxim Gorky and with Gorky's help, met Vladimir Lenin. In his book Russia in the Shadows, Wells portrayed Russia as recovering from a total social collapse, "the completest that has ever happened to any modern social organisation."[86] On 23 July 1934, after visiting U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Wells went to the Soviet Union and interviewed Joseph Stalin for three hours for the New Statesman magazine, which was extremely rare at that time. He told Stalin how he had seen 'the happy faces of healthy people' in contrast with his previous visit to Moscow in 1920.[87] However, he also criticised the lawlessness, class-based discrimination, state violence, and absence of free expression. Stalin enjoyed the conversation and replied accordingly. As the chairman of the London-based PEN Club, which protected the rights of authors to write without being intimidated, Wells hoped by his trip to USSR, he could win Stalin over by force of argument. Before he left, he realized that no reform was to happen in the near future.[88][89]

Final years

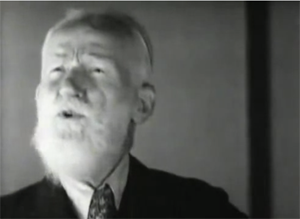

H. G. Wells in 1943

Wells's literary reputation declined as he spent his later years promoting causes that were rejected by most of his contemporaries as well as by younger authors whom he had previously influenced. In this connection, George Orwell described Wells as "too sane to understand the modern world".[90] G. K. Chesterton quipped: "Mr Wells is a born storyteller who has sold his birthright for a pot of message".[91]

Wells had diabetes,[92] and was a co-founder in 1934 of The Diabetic Association (now Diabetes UK, the leading charity for people with diabetes in the UK).[93]

On 28 October 1940, on the radio station KTSA in San Antonio, Texas, Wells took part in a radio interview with Orson Welles, who two years previously had performed a famous radio adaptation of The War of the Worlds. During the interview, by Charles C Shaw, a KTSA radio host, Wells admitted his surprise at the widespread panic that resulted from the broadcast but acknowledged his debt to Welles for increasing sales of one of his "more obscure" titles.[94]

Death

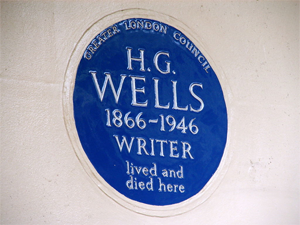

Commemorative blue plaque at Wells' final home in Regent's Park, London

Wells died of unspecified causes on 13 August 1946, aged 79, at his home at 13 Hanover Terrace, overlooking Regent's Park, London.[95][96] In his preface to the 1941 edition of The War in the Air, Wells had stated that his epitaph should be: "I told you so. You damned fools".[97] Wells' body was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium on 16 August 1946; his ashes were subsequently scattered into the English Channel at "Old Harry Rocks".[98]

A commemorative blue plaque in his honour was installed by the Greater London Council at his home in Regent's Park in 1966.[99]

Futurist

A renowned futurist and “visionary”, Wells foresaw the advent of aircraft, tanks, space travel, nuclear weapons, satellite television and something resembling the World Wide Web.[7] Asserting that “Wells visions of the future remain unsurpassed”, John Higgs, author of Stranger Than We Can Imagine: Making Sense of the Twentieth Century, states that in the late 19th century Wells “saw the coming century clearer than anyone else. He anticipated wars in the air, the sexual revolution, motorised transport causing the growth of suburbs and a proto-Wikipedia he called the “world brain”. He foresaw world wars creating a federalised Europe. Britain, he thought, would not fit comfortably in this New Europe and would identify more with the US and other English-speaking countries. In his novel The World Set Free, he imagined an “atomic bomb” of terrifying power that would be dropped from aeroplanes. This was an extraordinary insight for an author writing in 1913, and it made a deep impression on Winston Churchill.”[100]

In a review of The Time Machine for the New Yorker magazine, Brad Leithauser writes, “At the base of Wells’s great visionary exploit is this rational, ultimately scientific attempt to tease out the potential future consequences of present conditions—not as they might arise in a few years, or even decades, but millennia hence, epochs hence. He is world literature’s Great Extrapolator. Like no other fiction writer before him, he embraced “deep time.”[101]

Political views

Main article: Political views of H.G. Wells

An avid reader of Wells' books, Winston Churchill wrote to the author in 1906, stating "I owe you a great debt", two days before giving an early landmark speech that the state should support its citizens, providing pensions, insurance and child welfare.[102]

A socialist, Wells’ contemporary political impact was limited, excluding his fiction's positivist stance on the leaps that could be made by physics towards world peace. Winston Churchill was an avid reader of Wells' books, and after they first met in 1902 they kept in touch until Wells died in 1946.[102] As a junior minister Churchill borrowed lines from Wells for one of his most famous early landmark speeches in 1906, and as Prime Minister the phrase "the gathering storm" — used by Churchill to describe the rise of Nazi Germany — had been written by Wells in The War of the Worlds, which depicts an attack on Britain by Martians.[102] Wells's extensive writings on equality and human rights, most notably his most influential work, The Rights of Man (1940), laid the groundwork for the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was adopted by the United Nations shortly after his death.[103][104]

His efforts regarding the League of Nations, on which he collaborated on the project with Leonard Woolf with the booklets The Idea of a League of Nations, Prolegomena to the Study of World Organization, and The Way of the League of Nations, became a disappointment as the organization turned out to be a weak one unable to prevent the Second World War, which itself occurred towards the very end of his life and only increased the pessimistic side of his nature.[105] In his last book Mind at the End of Its Tether (1945), he considered the idea that humanity being replaced by another species might not be a bad idea. He referred to the era between the two World Wars as "The Age of Frustration".[106]

H. G. Wells

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 7/4/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

The vigilance, albeit belated, of the British security service provides a window on the membership and activities of the October Club. Cambridge student communism in the 1930s spawned a celebrated cluster of Soviet agents at the heart of the British establishment. When this became apparent twenty years later with the defection to Moscow of two senior figures in British intelligence, Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean, MI5 became alarmed about how little they knew about Oxford communists at that time. They resolved to find out -- and were assiduous in approaching one-time members of the October Club who might be happy to share information about their former comrades. They were fortunate that the club's founder -- an American, Frank Strauss Meyer -- had recanted of his student communism and was happy to cooperate. [33] And still more valuable for MI5, another onetime member of the October Club, Francois Lafitte, divulged the names of all the Oxford student communists he could recall. Freda and Bedi were both on the list -- 'Seemed to me both to be close fellow-travellers. They married and went to Lahore ... ' -- and so too was Sajjad Zaheer, a 'very capable Indian and close friend of Olive Shapley.' [34]

Meyer and others established the October Club at the close of 1931, as a left-wing breakaway from the Labour Club. 'We decided to organize the October Club quite on our own, with the idea of using it to attract those interested in Communism and forming a guiding group inside it,' Meyer told MI5. 'At the beginning we had considerable contempt for the official Communist Party' -- a suspicion which was reciprocated. The Communist Party of Great Britain was at the time a small, workerist and distinctly sectarian force of a few thousand members. [35] By the spring of 1932, the October Club's core of ten or twelve activists had joined the party, and after its first year of activity that number had doubled and the club's membership was in the hundreds. In its early months, the October Club achieved attention with a string of big name speakers, one of whom, H.G. Wells, was subject to barracking for being critical of Moscow. Escapades such as singing the communist anthem 'The Internationale' at an Armistice Day service to honour the war dead and street fights with fascist students earned the club a certain notoriety. The political atmosphere at the time was highly charged, and the Oxford Union's resounding endorsement in February 1933 of a motion 'that this House will in no circumstances fight for its King and Country' caught global attention; the Daily Express lamented that 'the woozy-minded Communists, the practical jokers, and the sexual indeterminates of Oxford have scored a great success with the publicity that has followed this victory.' In the wake of that controversy, a book on Young Oxford and War was rushed out, edited by V.K. Krishna Menon and with contributions from students of various political loyalties. Dick Freeman, a founder of the October Club, wrote about the radicalisation of Oxford students, and the emotional and political impact of the reception and support given in October 1932 to unemployed hunger marchers from the north -- for many students the first direct experience of the poverty and misery of those without work. [36] The October Club made a political impact out of all proportion to its numbers. Michael Foot, an Oxford student (and a Liberal) at the time and later a leader of the Labour Party, commended it as 'the most lively and enthusiastic club in Oxford.' [37]

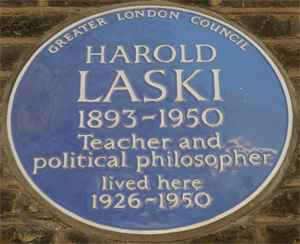

Freda, along with many October Club stalwarts, had started out as a member of the Labour Club and then gravitated towards the breakaway group. 'The idealism of our generation was the idealism of helping the underprivileged,' she recalled. 'If the Labour Club to which I belonged ... had any meaning, it was showing that we cared if people hadn't got enough food when they took the government dole, and we did care if the hunger marchers went all the way from Reading to London, we cared if there were children in the slums with no shoes and that children hadn't got enough food.' Her years in Oxford, she said, were 'radical years ... we used to attend all the clubs like the Labour Club and later on the more extreme October Club ... The whole atmosphere was electric with social demands and social change. We were, as it were, the Depression generation.' [38] Both Freda and Bedi attended the socialist G.D.H. Cole's lectures and Harold Laski's seminars on Marx and -- in a joint activity which served to demonstrate both their intellectual and personal compatibility -- they scoured the British Library to track down Marx's journalism about India....

When the playwright George Bernard Shaw came to address the October Club, Sajjad Zaheer recalled, there were fears of an attempt to stop him speaking. 'So we decided to defend that meeting and among the chief defenders of the meeting was my dear friend, B.P.L. Bedi, who was at that time physically the strongest man at Oxford.' [41]

-- 2: The Gates of the World. The Lives of Freda: The Political, Spiritual and Personal Journeys of Freda Bedi -- EXCERPT, by Andrew Whitehead

And how will the new republic treat the inferior races? How will it deal with the black? how will it deal with the yellow man? how will it tackle that alleged termite in the civilized woodwork, the Jew? Certainly not as races at all. It will aim to establish, and it will at last, though probably only after a second century has passed, establish a world state with a common language and a common rule. All over the world its roads, its standards, its laws, and its apparatus of control will run. It will, I have said, make the multiplication of those who fall behind a certain standard of social efficiency unpleasant and difficult… The Jew will probably lose much of his particularism, intermarry with Gentiles, and cease to be a physically distinct element in human affairs in a century or so. But much of his moral tradition will, I hope, never die. … And for the rest, those swarms of black, and brown, and dirty-white, and yellow people, who do not come into the new needs of efficiency?

Well, the world is a world, not a charitable institution, and I take it they will have to go. The whole tenor and meaning of the world, as I see it, is that they have to go. So far as they fail to develop sane, vigorous, and distinctive personalities for the great world of the future, it is their portion to die out and disappear.

-- Political Views of H.G. Wells

The Coefficients was a monthly dining club founded in 1902 by the Fabian campaigners Sidney and Beatrice Webb as a forum for British socialist reformers and imperialists of the Edwardian era. The name of the dining club was a reflection of the group's focus on "efficiency".

The Webbs proposed that the club's membership reflect the entire gamut of political beliefs, and "proposed to collect politicians from each of the parties". Representing the Liberal Imperialists were Sir Edward Grey and Richard Burdon Haldane; the Tories were represented by economist William Hewins and editor of the National Review Leopold Maxse; and the British military was represented by Leo Amery, an "expert on the conditions of the army", and Carlyon Bellairs, a naval officer.

The club's membership included:

• H. G. Wells, novelist

-- Coefficients (dining club), by Wikipedia

H. G. Wells

Photograph by George Charles Beresford, 1920

Born Herbert George Wells

21 September 1866

Bromley, Kent, England

Died 13 August 1946 (aged 79)

Regent's Park, London, England

Occupation Novelist, teacher, historian, journalist

Alma mater Royal College of Science (Imperial College London)

Genre Science fiction (notably social science fiction), social realism

Subject World history, progress

Notable works

The Outline of History

The Country of the Blind

The Red Room

Fiction:

The Time Machine

The Invisible Man

The War of the Worlds

The Island of Doctor Moreau

The First Men in the Moon

The Shape of Things to Come

When the Sleeper Wakes

Years active 1895–1946

Spouse Isabel Mary Wells

(1891–1894, divorced)

Amy Catherine Robbins (1895–1927, her death)

Children George Phillip "G. P." Wells (1901–1985)

Frank Richard Wells (1903–1982)

Anna-Jane Kennard (1909–2010[1][2])

Anthony West (1914–1987)

Relatives Joseph Wells (father)

Sarah Neal (mother)

Herbert George Wells[3][4] (21 September 1866 – 13 August 1946) was an English writer. He was prolific in many genres, writing dozens of novels, short stories, and works of social commentary, satire, biography, and autobiography, and even including two books on recreational war games. He is now best remembered for his science fiction novels and is often called a "father of science fiction", along with Jules Verne and Hugo Gernsback.[5][6][a]

During his own lifetime, however, he was most prominent as a forward-looking, even prophetic social critic who devoted his literary talents to the development of a progressive vision on a global scale. A futurist, he wrote a number of utopian works and foresaw the advent of aircraft, tanks, space travel, nuclear weapons, satellite television and something resembling the World Wide Web.[7] His science fiction imagined time travel, alien invasion, invisibility, and biological engineering. Brian Aldiss referred to Wells as the "Shakespeare of science fiction".[8] Wells rendered his works convincing by instilling commonplace detail alongside a single extraordinary assumption – dubbed “Wells’s law” – leading Joseph Conrad to hail him in 1898 as "O Realist of the Fantastic!".[9] His most notable science fiction works include The Time Machine (1895), The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897), The War of the Worlds (1898) and the military science fiction The War in the Air (1907). Wells was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature four times.[10]

Wells's earliest specialised training was in biology, and his thinking on ethical matters took place in a specifically and fundamentally Darwinian context.[11] He was also from an early date an outspoken socialist, often (but not always, as at the beginning of the First World War) sympathising with pacifist views. His later works became increasingly political and didactic, and he wrote little science fiction, while he sometimes indicated on official documents that his profession was that of journalist.[12] Novels such as Kipps and The History of Mr Polly, which describe lower-middle-class life, led to the suggestion that he was a worthy successor to Charles Dickens,[13] but Wells described a range of social strata and even attempted, in Tono-Bungay (1909), a diagnosis of English society as a whole. Wells was a diabetic and co-founded the charity The Diabetic Association (known today as Diabetes UK) in 1934.[14]

Life

Early life

Herbert George Wells was born at Atlas House, 162 High Street in Bromley, Kent,[15] on 21 September 1866.[4] Called "Bertie" in the family, he was the fourth and last child of Joseph Wells (a former domestic gardener, and at the time a shopkeeper and professional cricketer) and his wife, Sarah Neal (a former domestic servant). An inheritance had allowed the family to acquire a shop in which they sold china and sporting goods, although it failed to prosper: the stock was old and worn out, and the location was poor. Joseph Wells managed to earn a meagre income, but little of it came from the shop and he received an unsteady amount of money from playing professional cricket for the Kent county team.[16] Payment for skilled bowlers and batsmen came from voluntary donations afterwards, or from small payments from the clubs where matches were played.

A defining incident of young Wells's life was an accident in 1874 that left him bedridden with a broken leg.[4] To pass the time he began to read books from the local library, brought to him by his father. He soon became devoted to the other worlds and lives to which books gave him access; they also stimulated his desire to write. Later that year he entered Thomas Morley's Commercial Academy, a private school founded in 1849, following the bankruptcy of Morley's earlier school. The teaching was erratic, the curriculum mostly focused, Wells later said, on producing copperplate handwriting and doing the sort of sums useful to tradesmen. Wells continued at Morley's Academy until 1880. In 1877, his father, Joseph Wells, suffered a fractured thigh. The accident effectively put an end to Joseph's career as a cricketer, and his subsequent earnings as a shopkeeper were not enough to compensate for the loss of the primary source of family income.[17]

Wells spent the winter of 1887-88 convalescing at Uppark, where his mother, Sarah, was housekeeper.[18]

No longer able to support themselves financially, the family instead sought to place their sons as apprentices in various occupations.[19] From 1880 to 1883, Wells had an unhappy apprenticeship as a draper at the Southsea Drapery Emporium, Hyde's.[20] His experiences at Hyde's, where he worked a thirteen-hour day and slept in a dormitory with other apprentices,[15] later inspired his novels The Wheels of Chance, The History of Mr Polly, and Kipps, which portray the life of a draper's apprentice as well as providing a critique of society's distribution of wealth.[21]

Wells's parents had a turbulent marriage, owing primarily to his mother's being a Protestant and his father's being a freethinker. When his mother returned to work as a lady's maid (at Uppark, a country house in Sussex), one of the conditions of work was that she would not be permitted to have living space for her husband and children. Thereafter, she and Joseph lived separate lives, though they never divorced and remained faithful to each other. As a consequence, Herbert's personal troubles increased as he subsequently failed as a draper and also, later, as a chemist's assistant. However, Uppark had a magnificent library in which he immersed himself, reading many classic works, including Plato's Republic, Thomas More's Utopia, and the works of Daniel Defoe.[22] This would be the beginning of Wells's venture into literature.

Teacher

Wells studying in London c. 1890

In October 1879, Wells's mother arranged through a distant relative, Arthur Williams, for him to join the National School at Wookey in Somerset as a pupil–teacher, a senior pupil who acted as a teacher of younger children.[20] In December that year, however, Williams was dismissed for irregularities in his qualifications and Wells was returned to Uppark. After a short apprenticeship at a chemist in nearby Midhurst and an even shorter stay as a boarder at Midhurst Grammar School, he signed his apprenticeship papers at Hyde's. In 1883, Wells persuaded his parents to release him from the apprenticeship, taking an opportunity offered by Midhurst Grammar School again to become a pupil–teacher; his proficiency in Latin and science during his earlier short stay had been remembered.[16][20]

The years he spent in Southsea had been the most miserable of his life to that point, but his good fortune at securing a position at Midhurst Grammar School meant that Wells could continue his self-education in earnest.[16] The following year, Wells won a scholarship to the Normal School of Science (later the Royal College of Science in South Kensington, now part of Imperial College London) in London, studying biology under Thomas Henry Huxley.[23] As an alumnus, he later helped to set up the Royal College of Science Association, of which he became the first president in 1909. Wells studied in his new school until 1887, with a weekly allowance of 21 shillings (a guinea) thanks to his scholarship. This ought to have been a comfortable sum of money (at the time many working class families had "round about a pound a week" as their entire household income)[24] yet in his Experiment in Autobiography, Wells speaks of constantly being hungry, and indeed photographs of him at the time show a youth who is very thin and malnourished.[25]

H. G. Wells in 1907 at the door of his house at Sandgate

He soon entered the Debating Society of the school. These years mark the beginning of his interest in a possible reformation of society. At first approaching the subject through Plato's Republic, he soon turned to contemporary ideas of socialism as expressed by the recently formed Fabian Society and free lectures delivered at Kelmscott House, the home of William Morris. He was also among the founders of The Science School Journal, a school magazine that allowed him to express his views on literature and society, as well as trying his hand at fiction; a precursor to his novel The Time Machine was published in the journal under the title The Chronic Argonauts. The school year 1886–87 was the last year of his studies.[23]

During 1888, Wells stayed in Stoke-on-Trent, living in Basford. The unique environment of The Potteries was certainly an inspiration. He wrote in a letter to a friend from the area that "the district made an immense impression on me." The inspiration for some of his descriptions in The War of the Worlds is thought to have come from his short time spent here, seeing the iron foundry furnaces burn over the city, shooting huge red light into the skies. His stay in The Potteries also resulted in the macabre short story "The Cone" (1895, contemporaneous with his famous The Time Machine), set in the north of the city.[26]

After teaching for some time, he was briefly on the staff of Holt Academy in Wales[27] – Wells found it necessary to supplement his knowledge relating to educational principles and methodology and entered the College of Preceptors (College of Teachers). He later received his Licentiate and Fellowship FCP diplomas from the College. It was not until 1890 that Wells earned a Bachelor of Science degree in zoology from the University of London External Programme. In 1889–90, he managed to find a post as a teacher at Henley House School in London, where he taught A. A. Milne (whose father ran the school).[28][29] His first published work was a Text-Book of Biology in two volumes (1893).[30]

Upon leaving the Normal School of Science, Wells was left without a source of income. His aunt Mary—his father's sister-in-law—invited him to stay with her for a while, which solved his immediate problem of accommodation. During his stay at his aunt's residence, he grew increasingly interested in her daughter, Isabel. He would later go on to court her. To earn money, he began writing short humorous articles for journals such as The Pall Mall Gazette, later collecting these in volume form as Select Conversations with an Uncle (1895) and Certain Personal Matters (1897). So prolific did Wells become at this mode of journalism that many of his early pieces remain unidentified. According to David C Smith, "Most of Wells's occasional pieces have not been collected, and many have not even been identified as his. Wells did not automatically receive the byline his reputation demanded until after 1896 or so ... As a result, many of his early pieces are unknown. It is obvious that many early Wells items have been lost."[31] His success with these shorter pieces encouraged him to write book-length work, and he published his first novel, The Time Machine, in 1895.[32]

Personal life

141 Maybury Rd, Woking, where Wells lived from May 1895 until late 1896[33]

In 1891, Wells married his cousin Isabel Mary Wells (1865–1931; from 1902 Isabel Mary Smith). The couple agreed to separate in 1894, when he had fallen in love with one of his students, Amy Catherine Robbins (1872–1927; later known as Jane), with whom he moved to Woking, Surrey in May 1895. They lived in a rented house, 'Lynton', (now No.141) Maybury Road in the town centre for just under 18 months[34] and married at St Pancras register office in October 1895.[35] His short period in Woking was perhaps the most creative and productive of his whole writing career,[34] for while there he planned and wrote The War of the Worlds and The Time Machine, completed The Island of Doctor Moreau, wrote and published The Wonderful Visit and The Wheels of Chance, and began writing two other early books, When the Sleeper Wakes and Love and Mr Lewisham.[34][36]

In late summer 1896, Wells and Jane moved to a larger house in Worcester Park, near Kingston upon Thames, for two years; this lasted until his poor health took them to Sandgate, near Folkestone, where he constructed a large family home, Spade House, in 1901. He had two sons with Jane: George Philip (known as "Gip"; 1901–1985) and Frank Richard (1903–1982).[37] Jane died 6 October 1927, in Dunmow, at the age of 55.

Wells had affairs with a significant number of women.[38] In December 1909, he had a daughter, Anna-Jane, with the writer Amber Reeves,[39] whose parents, William and Maud Pember Reeves, he had met through the Fabian Society. Amber had married the barrister G. R. Blanco White in July of that year, as co-arranged by Wells. After Beatrice Webb voiced disapproval of Wells' "sordid intrigue" with Amber, he responded by lampooning Beatrice Webb and her husband Sidney Webb in his 1911 novel The New Machiavelli as 'Altiora and Oscar Bailey', a pair of short-sighted, bourgeois manipulators. Between 1910–1913, novelist Elizabeth von Arnim was one of his mistresses.[40] In 1914, he had a son, Anthony West (1914–1987), by the novelist and feminist Rebecca West, 26 years his junior.[41] In 1920–21, and intermittently until his death, he had a love affair with the American birth control activist Margaret Sanger.[42] Between 1924 and 1933 he partnered with the 22-year younger Dutch adventurer and writer Odette Keun, with whom he lived in Lou Pidou, a house they built together in Grasse, France. Wells dedicated his longest book to her (The World of William Clissold, 1926).[43] When visiting Maxim Gorky in Russia 1920, he had slept with Gorky's mistress Moura Budberg, then still Countess Benckendorf and 27 years his junior. In 1933, when she left Gorky and emigrated to London, their relationship renewed and she cared for him through his final illness. Wells asked her to marry him repeatedly, but Budberg strongly rejected his proposals.[44][45]

In Experiment in Autobiography (1934), Wells wrote: "I was never a great amorist, though I have loved several people very deeply".[46] David Lodge's novel A Man of Parts (2011)—a 'narrative based on factual sources' (author's note)—gives a convincing and generally sympathetic account of Wells's relations with the women mentioned above, and others.[47]

Director Simon Wells (born 1961), the author's great-grandson, was a consultant on the future scenes in Back to the Future Part II (1989).[48]

Artist

One of the ways that Wells expressed himself was through his drawings and sketches. One common location for these was the endpapers and title pages of his own diaries, and they covered a wide variety of topics, from political commentary to his feelings toward his literary contemporaries and his current romantic interests. During his marriage to Amy Catherine, whom he nicknamed Jane, he drew a considerable number of pictures, many of them being overt comments on their marriage. During this period, he called these pictures "picshuas".[49] These picshuas have been the topic of study by Wells scholars for many years, and in 2006, a book was published on the subject.[50]

Writer

Statue of a tripod from The War of the Worlds in Woking, England. The book is a seminal depiction of a conflict between mankind and an extraterrestrial race.

Some of his early novels, called "scientific romances", invented several themes now classic in science fiction in such works as The Time Machine, The Island of Doctor Moreau, The Invisible Man, The War of the Worlds, When the Sleeper Wakes, and The First Men in the Moon. He also wrote realistic novels that received critical acclaim, including Kipps and a critique of English culture during the Edwardian period, Tono-Bungay. Wells also wrote dozens of short stories and novellas, including, "The Flowering of the Strange Orchid", which helped bring the full impact of Darwin's revolutionary botanical ideas to a wider public, and was followed by many later successes such as "The Country of the Blind" (1904).[51]

According to James Gunn, one of Wells's major contributions to the science fiction genre was his approach, which he referred to as his "new system of ideas".[52] In his opinion, the author should always strive to make the story as credible as possible, even if both the writer and the reader knew certain elements are impossible, allowing the reader to accept the ideas as something that could really happen, today referred to as "the plausible impossible" and "suspension of disbelief". While neither invisibility nor time travel was new in speculative fiction, Wells added a sense of realism to the concepts which the readers were not familiar with. He conceived the idea of using a vehicle that allows an operator to travel purposely and selectively forwards or backwards in time. The term "time machine", coined by Wells, is now almost universally used to refer to such a vehicle.[22] He explained that while writing The Time Machine, he realized that "the more impossible the story I had to tell, the more ordinary must be the setting, and the circumstances in which I now set the Time Traveller were all that I could imagine of solid upper-class comforts."[53] In "Wells's Law", a science fiction story should contain only a single extraordinary assumption. Being aware the notion of magic as something real had disappeared from society, he, therefore, used scientific ideas and theories as a substitute for magic to justify the impossible. Wells's best-known statement of the "law" appears in his introduction to The Scientific Romances of H. G. Wells (1933),

As soon as the magic trick has been done the whole business of the fantasy writer is to keep everything else human and real. Touches of prosaic detail are imperative and a rigorous adherence to the hypothesis. Any extra fantasy outside the cardinal assumption immediately gives a touch of irresponsible silliness to the invention.[54]

Dr. Griffin / The Invisible Man is a brilliant research scientist who discovers a method of invisibility, but finds himself unable to reverse the process. An enthusiast of random and irresponsible violence, Griffin has become an iconic character in horror fiction.[55] The Island of Doctor Moreau sees a shipwrecked man left on the island home of Doctor Moreau, a mad scientist who creates human-like hybrid beings from animals via vivisection.[56] The earliest depiction of uplift, the novel deals with a number of philosophical themes, including pain and cruelty, moral responsibility, human identity, and human interference with nature.[57] Though Tono-Bungay is not a science-fiction novel, radioactive decay plays a small but consequential role in it. Radioactive decay plays a much larger role in The World Set Free (1914). This book contains what is surely his biggest prophetic "hit", with the first description of a nuclear weapon.[58] Scientists of the day were well aware that the natural decay of radium releases energy at a slow rate over thousands of years. The rate of release is too slow to have practical utility, but the total amount released is huge. Wells's novel revolves around an (unspecified) invention that accelerates the process of radioactive decay, producing bombs that explode with no more than the force of ordinary high explosives—but which "continue to explode" for days on end. "Nothing could have been more obvious to the people of the earlier twentieth century", he wrote, "than the rapidity with which war was becoming impossible ... [but] they did not see it until the atomic bombs burst in their fumbling hands".[58] In 1932, the physicist and conceiver of nuclear chain reaction Leó Szilárd read The World Set Free (the same year Sir James Chadwick discovered the neutron), a book which he said made a great impression on him.[59]

The H. G. Wells crater, located on the far side of the Moon, was named after the author of The First Men in the Moon (1901) in 1970.

Wells also wrote non-fiction. His first non-fiction bestseller was Anticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress upon Human Life and Thought (1901). When originally serialised in a magazine it was subtitled "An Experiment in Prophecy", and is considered his most explicitly futuristic work. It offered the immediate political message of the privileged sections of society continuing to bar capable men from other classes from advancement until war would force a need to employ those most able, rather than the traditional upper classes, as leaders. Anticipating what the world would be like in the year 2000, the book is interesting both for its hits (trains and cars resulting in the dispersion of populations from cities to suburbs; moral restrictions declining as men and women seek greater sexual freedom; the defeat of German militarism, and the existence of a European Union) and its misses (he did not expect successful aircraft before 1950, and averred that "my imagination refuses to see any sort of submarine doing anything but suffocate its crew and founder at sea").[60][61]

His bestselling two-volume work, The Outline of History (1920), began a new era of popularised world history. It received a mixed critical response from professional historians.[62] However, it was very popular amongst the general population and made Wells a rich man. Many other authors followed with "Outlines" of their own in other subjects. He reprised his Outline in 1922 with a much shorter popular work, A Short History of the World, a history book praised by Albert Einstein,[63] and two long efforts, The Science of Life (1930) and The Work, Wealth and Happiness of Mankind (1931).[64][65] The "Outlines" became sufficiently common for James Thurber to parody the trend in his humorous essay, "An Outline of Scientists"—indeed, Wells's Outline of History remains in print with a new 2005 edition, while A Short History of the World has been re-edited (2006).[66]

H. G. Wells c. 1918

From quite early in Wells's career, he sought a better way to organise society and wrote a number of Utopian novels. The first of these was A Modern Utopia (1905), which shows a worldwide utopia with "no imports but meteorites, and no exports at all";[67] two travellers from our world fall into its alternate history. The others usually begin with the world rushing to catastrophe, until people realise a better way of living: whether by mysterious gases from a comet causing people to behave rationally and abandoning a European war (In the Days of the Comet (1906)), or a world council of scientists taking over, as in The Shape of Things to Come (1933, which he later adapted for the 1936 Alexander Korda film, Things to Come). This depicted, all too accurately, the impending World War, with cities being destroyed by aerial bombs. He also portrayed the rise of fascist dictators in The Autocracy of Mr Parham (1930) and The Holy Terror (1939). Men Like Gods (1923) is also a utopian novel. Wells in this period was regarded as an enormously influential figure; the critic Malcolm Cowley stated: "by the time he was forty, his influence was wider than any other living English writer".[68]

Wells contemplates the ideas of nature and nurture and questions humanity in books such as The Island of Doctor Moreau. Not all his scientific romances ended in a Utopia, and Wells also wrote a dystopian novel, When the Sleeper Wakes (1899, rewritten as The Sleeper Awakes, 1910), which pictures a future society where the classes have become more and more separated, leading to a revolt of the masses against the rulers.[69] The Island of Doctor Moreau is even darker. The narrator, having been trapped on an island of animals vivisected (unsuccessfully) into human beings, eventually returns to England; like Gulliver on his return from the Houyhnhnms, he finds himself unable to shake off the perceptions of his fellow humans as barely civilised beasts, slowly reverting to their animal natures.[70]

Wells also wrote the preface for the first edition of W. N. P. Barbellion's diaries, The Journal of a Disappointed Man, published in 1919. Since "Barbellion" was the real author's pen name, many reviewers believed Wells to have been the true author of the Journal; Wells always denied this, despite being full of praise for the diaries.[71]

H. G. Wells, one day before his 60th birthday, on the front cover of Time magazine, 20 September 1926

In 1927, a Canadian teacher and writer Florence Deeks unsuccessfully sued Wells for infringement of copyright and breach of trust, claiming that much of The Outline of History had been plagiarised from her unpublished manuscript,[72] The Web of the World's Romance, which had spent nearly nine months in the hands of Wells's Canadian publisher, Macmillan Canada.[73] However, it was sworn on oath at the trial that the manuscript remained in Toronto in the safekeeping of Macmillan, and that Wells did not even know it existed, let alone had seen it.[74] The court found no proof of copying, and decided the similarities were due to the fact that the books had similar nature and both writers had access to the same sources.[75] In 2000, A. B. McKillop, a professor of history at Carleton University, produced a book on the case, The Spinster & The Prophet: Florence Deeks, H. G. Wells, and the Mystery of the Purloined Past.[76] According to McKillop, the lawsuit was unsuccessful due to the prejudice against a woman suing a well-known and famous male author, and he paints a detailed story based on the circumstantial evidence of the case.[77] In 2004, Denis N. Magnusson, Professor Emeritus of the Faculty of Law, Queen's University, Ontario, published an article on Deeks v. Wells. This re-examines the case in relation to McKillop's book. While having some sympathy for Deeks, he argues that she had a weak case that was not well presented, and though she may have met with sexism from her lawyers, she received a fair trial, adding that the law applied is essentially the same law that would be applied to a similar case today (i.e., 2004).[78]

In 1933, Wells predicted in The Shape of Things to Come that the world war he feared would begin in January 1940,[79] a prediction which ultimately came true four months early, in September 1939, with the outbreak of World War II.[80] In 1936, before the Royal Institution, Wells called for the compilation of a constantly growing and changing World Encyclopaedia, to be reviewed by outstanding authorities and made accessible to every human being. In 1938, he published a collection of essays on the future organisation of knowledge and education, World Brain, including the essay "The Idea of a Permanent World Encyclopaedia".[81]

Plaque by the H. G. Wells Society at Chiltern Court, Baker Street in the City of Westminster, London, where Wells lived between 1930 and 1936

Prior to 1933, Wells's books were widely read in Germany and Austria, and most of his science fiction works had been translated shortly after publication.[82] By 1933, he had attracted the attention of German officials because of his criticism of the political situation in Germany, and on 10 May 1933, Wells's books were burned by the Nazi youth in Berlin's Opernplatz, and his works were banned from libraries and book stores.[82] Wells, as president of PEN International (Poets, Essayists, Novelists), angered the Nazis by overseeing the expulsion of the German PEN club from the international body in 1934 following the German PEN's refusal to admit non-Aryan writers to its membership. At a PEN conference in Ragusa, Wells refused to yield to Nazi sympathisers who demanded that the exiled author Ernst Toller be prevented from speaking.[82] Near the end of the World War II, Allied forces discovered that the SS had compiled lists of people slated for immediate arrest during the invasion of Britain in the abandoned Operation Sea Lion, with Wells included in the alphabetical list of "The Black Book".[83]

Seeking a more structured way to play war games, Wells also wrote Floor Games (1911) followed by Little Wars (1913), which set out rules for fighting battles with toy soldiers (miniatures).[84] Little Wars is recognised today as the first recreational war game and Wells is regarded by gamers and hobbyists as "the Father of Miniature War Gaming".[85] A pacifist prior to the First World War, Wells stated "how much better is this amiable miniature [war] than the real thing".[84] According to Wells, the idea of the miniature war game developed from a visit by his friend Jerome K. Jerome. After dinner, Jerome began shooting down toy soldiers with a toy cannon and Wells joined in to compete.[84]

Travels to Russia

Wells visited Russia three times: 1914, 1920 and 1934. During his second visit, he saw his old friend Maxim Gorky and with Gorky's help, met Vladimir Lenin. In his book Russia in the Shadows, Wells portrayed Russia as recovering from a total social collapse, "the completest that has ever happened to any modern social organisation."[86] On 23 July 1934, after visiting U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Wells went to the Soviet Union and interviewed Joseph Stalin for three hours for the New Statesman magazine, which was extremely rare at that time. He told Stalin how he had seen 'the happy faces of healthy people' in contrast with his previous visit to Moscow in 1920.[87] However, he also criticised the lawlessness, class-based discrimination, state violence, and absence of free expression. Stalin enjoyed the conversation and replied accordingly. As the chairman of the London-based PEN Club, which protected the rights of authors to write without being intimidated, Wells hoped by his trip to USSR, he could win Stalin over by force of argument. Before he left, he realized that no reform was to happen in the near future.[88][89]

Final years

H. G. Wells in 1943

Wells's literary reputation declined as he spent his later years promoting causes that were rejected by most of his contemporaries as well as by younger authors whom he had previously influenced. In this connection, George Orwell described Wells as "too sane to understand the modern world".[90] G. K. Chesterton quipped: "Mr Wells is a born storyteller who has sold his birthright for a pot of message".[91]

Wells had diabetes,[92] and was a co-founder in 1934 of The Diabetic Association (now Diabetes UK, the leading charity for people with diabetes in the UK).[93]

On 28 October 1940, on the radio station KTSA in San Antonio, Texas, Wells took part in a radio interview with Orson Welles, who two years previously had performed a famous radio adaptation of The War of the Worlds. During the interview, by Charles C Shaw, a KTSA radio host, Wells admitted his surprise at the widespread panic that resulted from the broadcast but acknowledged his debt to Welles for increasing sales of one of his "more obscure" titles.[94]

Death

Commemorative blue plaque at Wells' final home in Regent's Park, London

Wells died of unspecified causes on 13 August 1946, aged 79, at his home at 13 Hanover Terrace, overlooking Regent's Park, London.[95][96] In his preface to the 1941 edition of The War in the Air, Wells had stated that his epitaph should be: "I told you so. You damned fools".[97] Wells' body was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium on 16 August 1946; his ashes were subsequently scattered into the English Channel at "Old Harry Rocks".[98]

A commemorative blue plaque in his honour was installed by the Greater London Council at his home in Regent's Park in 1966.[99]

Futurist

A renowned futurist and “visionary”, Wells foresaw the advent of aircraft, tanks, space travel, nuclear weapons, satellite television and something resembling the World Wide Web.[7] Asserting that “Wells visions of the future remain unsurpassed”, John Higgs, author of Stranger Than We Can Imagine: Making Sense of the Twentieth Century, states that in the late 19th century Wells “saw the coming century clearer than anyone else. He anticipated wars in the air, the sexual revolution, motorised transport causing the growth of suburbs and a proto-Wikipedia he called the “world brain”. He foresaw world wars creating a federalised Europe. Britain, he thought, would not fit comfortably in this New Europe and would identify more with the US and other English-speaking countries. In his novel The World Set Free, he imagined an “atomic bomb” of terrifying power that would be dropped from aeroplanes. This was an extraordinary insight for an author writing in 1913, and it made a deep impression on Winston Churchill.”[100]

In a review of The Time Machine for the New Yorker magazine, Brad Leithauser writes, “At the base of Wells’s great visionary exploit is this rational, ultimately scientific attempt to tease out the potential future consequences of present conditions—not as they might arise in a few years, or even decades, but millennia hence, epochs hence. He is world literature’s Great Extrapolator. Like no other fiction writer before him, he embraced “deep time.”[101]

Political views

Main article: Political views of H.G. Wells

An avid reader of Wells' books, Winston Churchill wrote to the author in 1906, stating "I owe you a great debt", two days before giving an early landmark speech that the state should support its citizens, providing pensions, insurance and child welfare.[102]

A socialist, Wells’ contemporary political impact was limited, excluding his fiction's positivist stance on the leaps that could be made by physics towards world peace. Winston Churchill was an avid reader of Wells' books, and after they first met in 1902 they kept in touch until Wells died in 1946.[102] As a junior minister Churchill borrowed lines from Wells for one of his most famous early landmark speeches in 1906, and as Prime Minister the phrase "the gathering storm" — used by Churchill to describe the rise of Nazi Germany — had been written by Wells in The War of the Worlds, which depicts an attack on Britain by Martians.[102] Wells's extensive writings on equality and human rights, most notably his most influential work, The Rights of Man (1940), laid the groundwork for the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was adopted by the United Nations shortly after his death.[103][104]