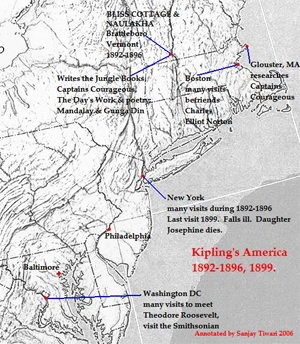

Part 2 of 2

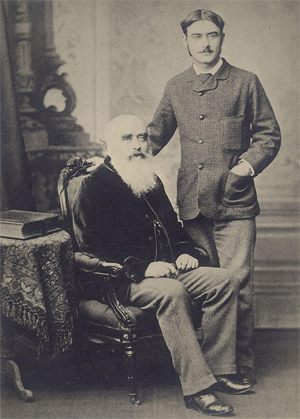

Death of John Kipling 2nd Lt John Kipling

2nd Lt John Kipling Memorial to 2nd Lt John Kipling in Burwash Parish Church, Sussex, England

Memorial to 2nd Lt John Kipling in Burwash Parish Church, Sussex, EnglandKipling's son John was killed in action in the First World War, at the Battle of Loos in September 1915, at age 18. John had initially wanted to join the Royal Navy, but having had his application turned down after a failed medical examination due to poor eyesight, he opted to apply for military service as an Army officer. But again, his eyesight was an issue during the medical examination. In fact, he tried twice to enlist but was rejected. His father had been lifelong friends with Lord Roberts, former commander-in-chief of the British Army, and colonel of the Irish Guards, and at Rudyard's request, John was accepted into the Irish Guards.[73]

John Kipling was sent to Loos two days into the battle in a reinforcement contingent. He was last seen stumbling through the mud blindly, with a possible facial injury. A body identified as his was found in 1992, although that identification has been challenged.[77][78][79] In 2015, the Commonwealth War Grave Commission confirmed that they had correctly identified the burial place of John Kipling;[80] they record his date of death as 27 September 1915, and that he is buried at St Mary's A.D.S. Cemetery, Haisnes.[81]

After his son's death, Kipling wrote, "If any question why we died / Tell them, because our fathers lied." It is speculated that these words may reveal his feelings of guilt at his role in getting John a commission in the Irish Guards.[82] Others, such as English professor Tracy Bilsing, contend that the line is referring to Kipling's disgust that British leaders failed to learn the lessons of the Boer War, and were not prepared for the struggle with Germany in 1914, with the "lie" of the "fathers" being that the British Army was prepared for any war when it was not.[73]

John's death has been linked to Kipling's 1916 poem "My Boy Jack", notably in the play My Boy Jack and its subsequent television adaptation, along with the documentary Rudyard Kipling: A Remembrance Tale. However, the poem was originally published at the head of a story about the Battle of Jutland and appears to refer to a death at sea; the 'Jack' referred to is probably a generic 'Jack Tar'.[83] In the Kipling family, Jack was the name of the family dog while John Kipling was always John, making the identification of the protagonist of "My Boy Jack" with John Kipling somewhat questionable. However, it is true that Kipling was emotionally devastated by the death of his son. It is said that Kipling helped assuage his grief over his son's death by reading the novels of Jane Austen aloud to his wife and daughter.[84] During the war, he wrote a booklet The Fringes of the Fleet[85] containing essays and poems on various nautical subjects of the war. Some of the poems were set to music by English composer Edward Elgar.

Kipling became friends with a French soldier named Maurice Hammoneau whose life had been saved in the First World War when his copy of Kim, which he had in his left breast pocket, stopped a bullet. Hammoneau presented Kipling with the book, with bullet still embedded, and his Croix de Guerre as a token of gratitude. They continued to correspond, and when Hammoneau had a son, Kipling insisted on returning the book and medal.[86]

On 1 August 1918, a poem, "The Old Volunteer", appeared under his name in The Times. The next day, he wrote to the newspaper to disclaim authorship, and a correction appeared. Although The Times employed a private detective to investigate, and the detective appears to have suspected Kipling himself of being the author, the identity of the hoaxer was never established.[87]

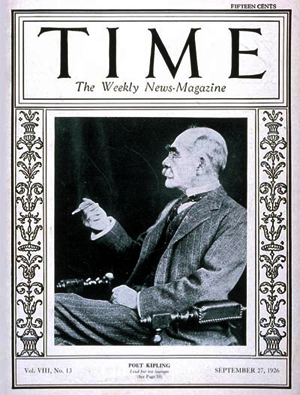

After the war (1918–1936) Kipling, aged 60, on the cover of Time magazine, 27 September 1926.

Kipling, aged 60, on the cover of Time magazine, 27 September 1926.Partly in response to John's death, Kipling joined Sir Fabian Ware's Imperial War Graves Commission (now the Commonwealth War Graves Commission), the group responsible for the garden-like British war graves that can be found to this day dotted along the former Western Front and all the other locations around the world where troops of the British Empire lie buried.

His most significant contributions to the project were his selection of the biblical phrase, "Their Name Liveth For Evermore" (Ecclesiasticus 44.14, KJV), found on the Stones of Remembrance in larger war cemeteries, and his suggestion of the phrase "Known unto God" for the gravestones of unidentified servicemen. He also chose the inscription "The Glorious Dead" on the Cenotaph, Whitehall, London. Additionally, he wrote a two-volume history of the Irish Guards, his son's regiment: it was published in 1923 and is considered to be one of the finest examples of regimental history.[88]

Kipling's moving short story, "The Gardener", depicts visits to the war cemeteries, and the poem "The King's Pilgrimage" (1922) depicts a journey which King George V made, touring the cemeteries and memorials under construction by the Imperial War Graves Commission. With the increasing popularity of the automobile, Kipling became a motoring correspondent for the British press, and wrote enthusiastically of his trips around England and abroad, even though he was usually driven by a chauffeur.

After the war, Kipling was sceptical about the Fourteen Points and the League of Nations, but he had great hopes that the United States would abandon isolationism and that the post-war world would be dominated by an Anglo-French-American alliance.[89] Kipling hoped that the United States would take on a League of Nations mandate for Armenia as the best way of preventing isolationism, and hoped that Theodore Roosevelt, whom Kipling admired, would once again become president.[89] Kipling was saddened by Roosevelt's death in 1919, believing that his friend was the only American politician capable of keeping the United States in the "game" of world politics.[90]

Kipling was very hostile towards communism, writing about the Bolshevik take-over in 1917 that one sixth of the world had "passed bodily out of civilization".[91] In a 1918 poem, Kipling wrote about Soviet Russia that everything good in Russia had now been destroyed by the Bolsheviks and all that was left was "the sound of weeping and the sight of burning fire, and the shadow of a people trampled into the mire".[91]

In 1920, Kipling co-founded the Liberty League[92] with Haggard and Lord Sydenham. This short-lived enterprise focused on promoting classic liberal ideals as a response to the rising power of communist tendencies within Great Britain, or, as Kipling put it, "to combat the advance of Bolshevism".[93][94]

Kipling (second from left) as rector of the University of St Andrews, Scotland in 1923

Kipling (second from left) as rector of the University of St Andrews, Scotland in 1923In 1922, Kipling, who had made reference to the work of engineers in some of his poems, such as "The Sons of Martha", "Sappers", and "McAndrew's Hymn",[95] and in other writings, including short story anthologies such as The Day's Work,[96] was asked by University of Toronto civil engineering professor Herbert E. T. Haultain for his assistance in developing a dignified obligation and ceremony for graduating engineering students. Kipling was enthusiastic in his response and shortly produced both, formally entitled "The Ritual of the Calling of an Engineer". Today, engineering graduates all across Canada are presented with an iron ring at the ceremony as a reminder of their obligation to society.[97][98] In 1922 Kipling also became Lord Rector of St Andrews University in Scotland, a three-year position.

Kipling, who was a Francophile, argued strongly for an Anglo-French alliance to uphold the peace, calling Britain and France in 1920 the "twin fortresses of European civilization".[99] Along the same lines, Kipling repeatedly warned against revising the Treaty of Versailles in Germany's favour, which he predicted would lead to a new world war.[99] An admirer of Raymond Poincaré, Kipling was one of the few British intellectuals who supported the French Occupation of the Ruhr in 1923 at a time when the British government and most public opinion was against the French position.[100] In contrast to the popular British view of Poincaré as a cruel bully intent on impoverishing Germany by seeking unreasonable reparations, Kipling argued that Poincaré was only rightfully trying to preserve France as a great power in the face of an unfavourable situation.[100] Kipling argued that even before 1914, Germany's larger economy and higher birth rate had made that country stronger than France; with much of France devastated by the war, and the French suffering heavy losses that the low French birth rate would have trouble replacing while Germany was mostly undamaged and still with a higher birth rate, he reasoned that the future would advantage German domination if Versailles were revised in Germany's favour. He wrote that it was madness for Britain to seek to pressure France to revise Versailles in Germany's favour.[100]

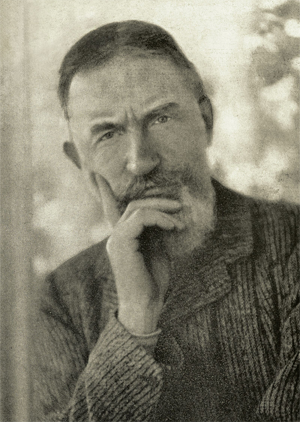

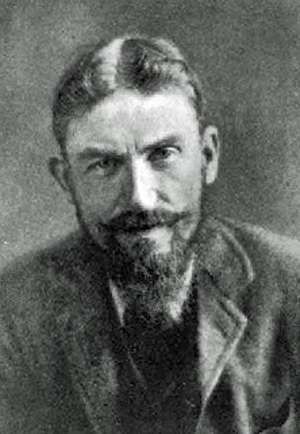

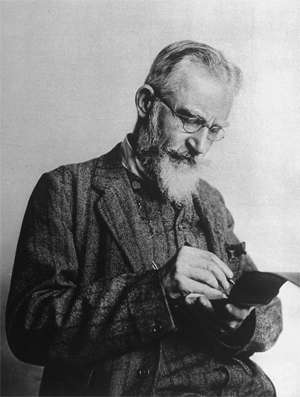

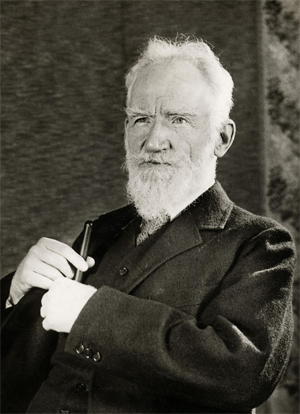

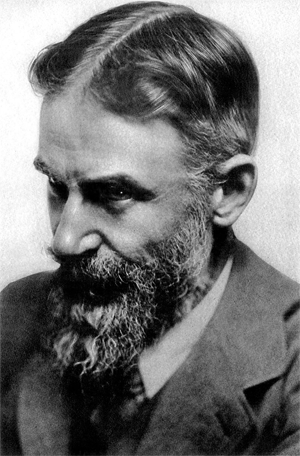

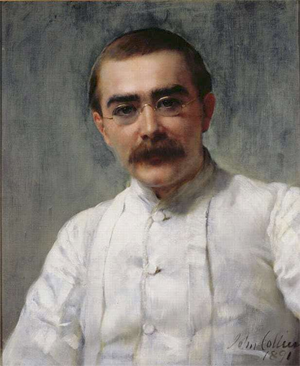

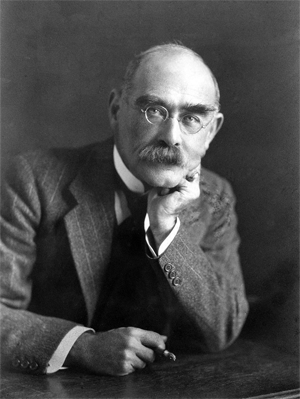

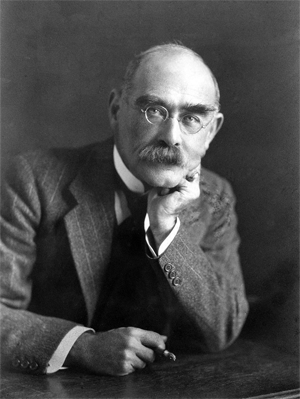

Kipling late in his life, portrait by Elliott & Fry.

Kipling late in his life, portrait by Elliott & Fry.In 1924, Kipling was opposed to the Labour government of Ramsay MacDonald as "Bolshevism without bullets", but believing that Labour was a communist front organisation, he took the view that "excited orders and instructions from Moscow" would expose Labour as such an organisation to the British people.[101] Kipling's views were on the right and though he admired Benito Mussolini to a certain extent for a time in the 1920s, Kipling was against fascism, writing that Oswald Mosley was "a bounder and an arriviste". By 1935, he called Mussolini a deranged and dangerous egomaniac and in 1933 wrote, "The Hitlerites are out for blood".[102]

Despite his anti-communism, the first major translations of Kipling into Russian took place during Lenin's rule in the early 1920s, and during the interwar period, Kipling was very popular with Russian readers. Many of the younger Russian poets and writers such as Konstantin Simonov were influenced by Kipling.[103] Kipling's clarity of style, his use of colloquial language and the way in which he used rhythm and rhyme were considered to be major innovations in poetry that appealed to many of the younger Russian poets.[104] Though it was obligatory for Soviet journals to begin translations of Kipling with an introduction attacking him as a "fascist" and an "imperialist", such was Kipling's popularity with Russian readers that his works were not banned in the Soviet Union until 1939 with the signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.[103] Kipling's work was unbanned in the Soviet Union in 1941 after Operation Barbarossa, when Britain become a Soviet ally, but his work was banned again, this time for good, with the Cold War in 1946.[105]

A left-facing swastika in 1911, a symbol of good luck.

A left-facing swastika in 1911, a symbol of good luck. Covers of two of Kipling's books from 1919 (l) and 1930 (r) showing the removal of the swastika

Covers of two of Kipling's books from 1919 (l) and 1930 (r) showing the removal of the swastikaMany older editions of Rudyard Kipling's books have a swastika printed on their covers associated with a picture of an elephant carrying a lotus flower, reflecting the influence of Indian culture. Kipling's use of the swastika was based on the Indian sun symbol conferring good luck and the Sanskrit word meaning "fortunate" or "well-being".[106] He used the swastika symbol in both right- and left-facing orientations, and it was in general use by others at the time.[107][108]

In a note to Edward Bok written after the death of Lockwood Kipling in 1911, Rudyard said: "I am sending with this for your acceptance, as some little memory of my father to whom you were so kind, the original of one of the plaques that he used to make for me. I thought it being the Swastika would be appropriate for your Swastika. May it bring you even more good fortune."[106] Once the Nazis came to power and usurped the swastika, Kipling ordered that it should no longer adorn his books.[106] Less than a year before his death, Kipling gave a speech (titled "An Undefended Island") to the Royal Society of St George on 6 May 1935, warning of the danger which Nazi Germany posed to Britain.[109]

Kipling scripted the first Royal Christmas Message, delivered via the BBC's Empire Service by George V in 1932.[110][111] In 1934, he published a short story in The Strand Magazine, "Proofs of Holy Writ", which postulated that William Shakespeare had helped to polish the prose of the King James Bible.[112]

DeathKipling kept writing until the early 1930s, but at a slower pace and with much less success than before. On the night of 12 January 1936 he suffered a haemorrhage in his small intestine. He underwent surgery but died less than a week later on 18 January 1936, at the age of 70 of a perforated duodenal ulcer.[113][114] His death had previously been incorrectly announced in a magazine, to which he wrote, "I've just read that I am dead. Don't forget to delete me from your list of subscribers."[115]

The pallbearers at the funeral included Kipling's cousin, the Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, and the marble casket was covered by a Union Jack.[116] Kipling was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium in northwest London, and his ashes interred at Poets' Corner, part of the South Transept of Westminster Abbey, next to the graves of Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy.[116]

LegacyIn 2010, the International Astronomical Union approved that a crater on the planet Mercury would be named after Kipling—one of ten newly discovered impact craters observed by the MESSENGER spacecraft in 2008–9.[117] In 2012, an extinct species of crocodile, Goniopholis kiplingi, was named in his honour, "in recognition for his enthusiasm for natural sciences".[118]

More than 50 unpublished poems by Kipling, discovered by the American scholar Thomas Pinney, were released for the first time in March 2013.[119]

Kipling's writing has strongly influenced other writers. Kipling's stories for adults remain in print and have garnered high praise from writers as different as Poul Anderson, Jorge Luis Borges, and Randall Jarrell who wrote that, "After you have read Kipling's fifty or seventy-five best stories you realize that few men have written this many stories of this much merit, and that very few have written more and better stories."[120]

His children's stories remain popular, and his Jungle Books have been made into several movies. The first was made by producer Alexander Korda, and other films have been produced by The Walt Disney Company. A number of his poems were set to music by Percy Grainger. A series of short films based on some of his stories was broadcast by the BBC in 1964.[121] Kipling's work is still popular today.

The poet T. S. Eliot edited A Choice of Kipling's Verse (1941) with an introductory essay.[122] Eliot was aware of the complaints that had been levelled against Kipling and he dismissed them one by one: that Kipling is 'a Tory' using his verse to transmit right wing political views, or 'a journalist' pandering to popular taste; while Eliot writes "I cannot find any justification for the charge that he held a doctrine of race superiority."[123] Eliot finds instead,

An immense gift for using words, an amazing curiosity and power of observation with his mind and with all his senses, the mask of the entertainer, and beyond that a queer gift of second sight, of transmitting messages from elsewhere, a gift so disconcerting when we are made aware of it that thenceforth we are never sure when it is not present: all this makes Kipling a writer impossible wholly to understand and quite impossible to belittle.

— T.S. Eliot[124]

Of Kipling's verse, such as his Barrack-Room Ballads, Eliot writes "of a number of poets who have written great poetry, only ... a very few whom I should call great verse writers. And unless I am mistaken, Kipling's position in this class is not only high, but unique."[125]

In response to Eliot, George Orwell wrote a long consideration of Kipling's work for Horizon in 1942, noting that although as a "jingo imperialist" Kipling was "morally insensitive and aesthetically disgusting", his work had many qualities which ensured that while "every enlightened person has despised him ... nine-tenths of those enlightened persons are forgotten and Kipling is in some sense still there". Orwell said:

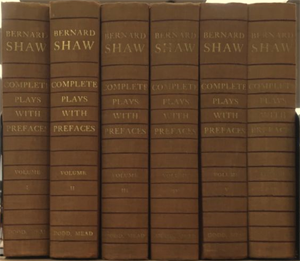

One reason for Kipling's power [was] his sense of responsibility, which made it possible for him to have a world-view, even though it happened to be a false one. Although he had no direct connexion with any political party, Kipling was a Conservative, a thing that does not exist nowadays. Those who now call themselves Conservatives are either Liberals, Fascists or the accomplices of Fascists. He identified himself with the ruling power and not with the opposition. In a gifted writer this seems to us strange and even disgusting, but it did have the advantage of giving Kipling a certain grip on reality. The ruling power is always faced with the question, 'In such and such circumstances, what would you do?', whereas the opposition is not obliged to take responsibility or make any real decisions. Where it is a permanent and pensioned opposition, as in England, the quality of its thought deteriorates accordingly. Moreover, anyone who starts out with a pessimistic, reactionary view of life tends to be justified by events, for Utopia never arrives and 'the gods of the copybook headings', as Kipling himself put it, always return. Kipling sold out to the British governing class, not financially but emotionally. This warped his political judgement, for the British ruling class were not what he imagined, and it led him into abysses of folly and snobbery, but he gained a corresponding advantage from having at least tried to imagine what action and responsibility are like. It is a great thing in his favour that he is not witty, not 'daring', has no wish to épater les bourgeois. He dealt largely in platitudes, and since we live in a world of platitudes, much of what he said sticks. Even his worst follies seem less shallow and less irritating than the 'enlightened' utterances of the same period, such as Wilde's epigrams or the collection of cracker-mottoes at the end of Man and Superman.

— George Orwell[126]

The poet Alison Brackenbury writes that "Kipling is poetry's Dickens, an outsider and journalist with an unrivalled ear for sound and speech."[127]

The English folk singer Peter Bellamy was a great lover of Kipling's poetry, much of which he believed to have been influenced by English traditional folk forms. He recorded several albums of Kipling's verse set to traditional airs, or to tunes of his own composition written in traditional style.[128] However, in the case of the bawdy folk song, "The Bastard King of England", which is commonly credited to Kipling, it is believed that the song is actually misattributed.[129]

Kipling is often quoted in discussions of contemporary British political and social issues. In 1911, Kipling wrote the poem The Reeds of Runnymede that celebrated Magna Carta, and summoned up the vision of the ‘stubborn Englishry’ determined to defend their rights. In 1996, the following verses of the poem were quoted by former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher warning against the encroachment of the European Union on national sovereignty:

At Runnymede, at Runnymede,

Oh, hear the reeds at Runnymede:

‘You musn’t sell, delay, deny,

A freeman’s right or liberty.

It wakes the stubborn Englishry,

We saw ’em roused at Runnymede!

… And still when Mob or Monarch lays

Too rude a hand on English ways,

The whisper wakes, the shudder plays,

Across the reeds at Runnymede.

And Thames, that knows the mood of kings,

And crowds and priests and suchlike things,

Rolls deep and dreadful as he brings

Their warning down from Runnymede![130]

Political singer-songwriter Billy Bragg, who attempts to reclaim English nationalism from the right-wing, has reclaimed Kipling for an inclusive sense of Englishness.[131] Kipling's enduring relevance has been noted in the United States, as it has become involved in Afghanistan and other areas about which he wrote.[132][133][134]

Links with camping and ScoutingIn 1903, Kipling gave permission to Elizabeth Ford Holt to borrow themes from the Jungle Books to establish Camp Mowglis, a summer camp for boys on the shores of Newfound Lake in New Hampshire. Throughout their lives, Kipling and his wife Carrie maintained an active interest in Camp Mowglis, which is still in operation and continues the traditions that Kipling inspired. Buildings at Mowglis have names such as Akela, Toomai, Baloo, and Panther. The campers are referred to as "the Pack", from the youngest "Cubs" to the oldest campers living in "Den".[135]

Kipling's links with the Scouting movements were also strong. Robert Baden-Powell, the founder of Scouting, used many themes from The Jungle Book stories and Kim in setting up his junior movement, the Wolf Cubs. These connections still exist today, such as the continued popularity of "Kim's Game" in the Scouting movement. The movement is named after Mowgli's adopted wolf family, and the adult helpers of Wolf Cub Packs adopt names taken from The Jungle Book, especially the adult leader who is called Akela after the leader of the Seeonee wolf pack.[136]

Kipling's home at Burwash Bateman's, Kipling's beloved home – which he referred to as "A good and peaceable place" – in Burwash, East Sussex, is now a public museum dedicated to the author.[137]

Bateman's, Kipling's beloved home – which he referred to as "A good and peaceable place" – in Burwash, East Sussex, is now a public museum dedicated to the author.[137]After the death of Kipling's wife in 1939, his house, Bateman's in Burwash, East Sussex, South East England, where he had lived from 1902 until 1936, was bequeathed to the National Trust and is now a public museum dedicated to the author. Elsie Bambridge, his only child who lived to maturity, died childless in 1976, and also bequeathed her copyrights to the National Trust, which in turn donated them to the University of Sussex to ensure better public access.[138]

Novelist and poet Sir Kingsley Amis wrote a poem, 'Kipling at Bateman's', after visiting Kipling's Burwash home (Amis' father had lived in Burwash briefly in the 1960s) as part of a BBC television series on writers and their houses.[139]

In 2003, actor Ralph Fiennes read excerpts from Kipling's works from the study in Bateman's, including, The Jungle Book, Something of Myself, Kim, and The Just So Stories, and poems, including "If ..." and "My Boy Jack", for a CD published by the National Trust.[140][141]

Reputation in IndiaIn modern-day India, whence he drew much of his material, Kipling's reputation remains controversial, especially amongst modern nationalists and some post-colonial critics. Rudyard Kipling was a prominent supporter of Colonel Reginald Dyer, who was responsible for the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar (in the province of Punjab). Kipling called Dyer "the man who saved India" and also initiated collections for the latter's homecoming prize.[142] However, Subhash Chopra, in his book Kipling Sahib – the Raj Patriot, writes that the benefit fund was started by The Morning Post newspaper and not by Kipling and that Kipling made no contribution to the Dyer fund. While Kipling's name was conspicuously absent from the list of donors as published in The Morning Post, he clearly admired Dyer.[143]

Other contemporary Indian intellectuals such as Ashis Nandy have taken a more nuanced view of his work. Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of independent India, often described Kipling's novel Kim as one of his favourite books.[144][145]

G V Desani, an Indian writer of fiction, had a more negative opinion of Kipling. He alludes to Kipling in his novel, All About H. Hatterr:

I happen to pick up R. Kipling's autobiographical "Kim".

Therein, this self-appointed whiteman's burden-bearing sherpa feller's stated how, in the Orient, blokes hit the road and think nothing of walking a thousand miles in search of something.

Indian writer Khushwant Singh wrote in 2001 that he considers Kipling's "If—" "the essence of the message of The Gita in English",[146] referring to the Bhagavad Gita, an ancient Indian scripture.

Indian writer R. K. Narayan said, "Kipling, the supposed expert writer on India, showed a better understanding of the mind of the animals in the jungle than of the men in an Indian home or the marketplace."[147]

In November 2007, it was announced that Kipling's birth home in the campus of the J J School of Art in Mumbai would be turned into a museum celebrating the author and his works.[148]

BibliographyMain article: Rudyard Kipling bibliography

Kipling's bibliography includes fiction (including novels and short stories), non-fiction, and poetry. Several of his works were collaborations.

See also• List of Nobel laureates in Literature

• HMS Birkenhead (1845)

References1. The Times, (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12

2. "The Man who would be King". Notes on the text by John McGivering. kiplingsociety.co.uk

3. Rutherford, Andrew (1987). General Preface to the Editions of Rudyard Kipling, in "Puck of Pook's Hill and Rewards and Fairies", by Rudyard Kipling. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-282575-5

4. Jump up to:a b c d e Rutherford, Andrew (1987). Introduction to the Oxford World's Classics edition of "Plain Tales from the Hills", by Rudyard Kipling. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-281652-7

5. James Joyce considered Tolstoy, Kipling and D'Annunzio to be the "three writers of the nineteenth century who had the greatest natural talents", but that "he did not fulfill that promise". He also noted that the three writers all "had semi-fanatic ideas about religion, or about patriotism". Diary of David Fleischman, 21 July 1938, quoted in James Joyce by Richard Ellmann, p. 661, Oxford University Press (1983) ISBN 0-19-281465-6

6. Alfred Nobel Foundation. "Who is the youngest ever to receive a Nobel Prize, and who is the oldest?". Nobelprize.com. p. 409. Archived from the original on 25 September 2006. Retrieved 30 September 2006.

7. Birkenhead, Lord. (1978). Rudyard Kipling, Appendix B, "Honours and Awards". Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London; Random House Inc., New York

8. Lewis, Lisa. (1995). Introduction to the Oxford World's Classics edition of "Just So Stories", by Rudyard Kipling. Oxford University Press. pp.xv-xlii. ISBN 0-19-282276-4

9. Quigley, Isabel. (1987). Introduction to the Oxford World's Classics edition of "The Complete Stalky & Co.", by Rudyard Kipling. Oxford University Press. pp. xiii–xxviii. ISBN 0-19-281660-8

10. Said, Edward. (1993). Culture and Imperialism. London: Chatto & Windus. p. 196. ISBN 0-679-75054-1.

11. Sandison, Alan. (1987). Introduction to the Oxford World's Classics edition of Kim, by Rudyard Kipling. Oxford University Press. pp. xiii–xxx. ISBN 0-19-281674-8

12. Orwell, George (30 September 2006). "Essay on Kipling". Archived from the original on 18 September 2006. Retrieved 30 September2006.

13. Douglas Kerr, University of Hong Kong (30 May 2002). "Rudyard Kipling." The Literary Encyclopedia. The Literary Dictionary Company. 26 September 2006.

14. Carrington, C.E. (Charles Edmund). (1955). Rudyard Kipling: His Life and Work. Macmillan & Co.

15. Flanders, Judith. (2005). A Circle of Sisters: Alice Kipling, Georgiana Burne-Jones, Agnes Poynter, and Louisa Baldwin. W.W. Norton and Company, New York. ISBN 0-393-05210-9

16. Gilmour

17. "My Rival" 1885. Notes edited by John Radcliffe. kiplingsociety.co.uk

18. Gilmour, p. 32

19. thepotteries.org (13 January 2002). "did you know . ..." The potteries.org. Retrieved 2 October 2006.

20. Ahmed, Zubair (27 November 2007). "Kipling's India home to become museum". BBC News. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

21. Sir J.J. College of Architecture (30 September 2006). "Campus". Sir J. J. College of Architecture, Mumbai. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2006.

22. Aklekar, Rajendra (12 August 2014). "Red tape keeps Kipling bungalow in disrepair". Mumbai Mirror. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

23. Kipling, Rudyard (1894) "To the City of Bombay", dedication to Seven Seas, Macmillan & Co.

24. Murphy, Bernice M. (21 June 1999). "Rudyard Kipling – A Brief Biography". School of English, The Queen's University of Belfast. Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 6 October2006.

25. Kipling, Rudyard (1935). "Something of Myself". Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2008.

26. Pinney, Thomas (2011) [2004]. "Kipling, (Joseph) Rudyard (1865–1936)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/34334.(Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

27. Pinney, Thomas (1995). "A Very Young Person, Notes on the text". Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

28. Carpenter, Humphrey and Prichard, Mari. (1984). Oxford Companion to Children's Literature. Oxford University Press. pp. 296–297. ISBN 0192115820.

29. Chums, No. 256, Vol. V, 4 August 1897, page 798

30. Neelam, S (8 June 2008). "Rudyard Kipling's Allahabad bungalow in shambles". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

31. Kipling, Rudyard,--1865-1936—Homes & haunts—India—Allahabad (from the collection of William Carpenter)". Library of Congress USA. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

32. Scott, p. 315

33. Pinney, Thomas (editor). Letters of Rudyard Kipling, volume 1. Macmillan & Co., London and NY

34. Hughes, James (2010). "Those Who Passed Through: Unusual Visits to Unlikely Places". New York History. 91 (2): 146–151. JSTOR 23185107.

35. Kipling, Rudyard (1956) Kipling: a selection of his stories and poems, Volume 2 pp.349 Doubleday, 1956

36. Coates, John D. (1997). The Day's Work: Kipling and the Idea of Sacrifice. Fairleigh University Press. p. 130. ISBN 083863754X.

37. Kaplan, Robert D. (1989) Lahore as Kipling Knew It. The New York Times. Retrieved 9 March 2008

38. Kipling, Rudyard (1996) Writings on Writing. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44527-2. see pp. 36, 173

39. Mallet, Phillip. (2003). Rudyard Kipling: A Literary Life. Palgrave Macmillan, New York. ISBN 0-333-55721-2

40. Ricketts, Harry. (1999). Rudyard Kipling: A life. Carroll and Graf Publishers Inc., New York. ISBN 0-7867-0711-9

41. Kipling, Rudyard. (1920). Letters of Travel (1892–1920). Macmillan & Co.

42. Nicolson, Adam. (2001). Carrie Kipling 1862–1939 : The Hated Wife. Faber & Faber, London. ISBN 0-571-20835-5

43. Pinney, Thomas (editor). Letters of Rudyard Kipling, volume 2. Macmillan & Co.

44. Kipling, Rudyard. 1899. The White Man's Burden. Published simultaneously in The Times, London, and McClure's Magazine (U.S.) 12 February 1899

45. Snodgrass, Chris. (2002). A Companion to Victorian Poetry. Blackwell, Oxford

46. Kipling, Rudyard. (July 1897). "Recessional'". The Times, London

47. "Something of Myself", pub. 1935, South Africa Chapter

48. Reilly, Bernard F., Center for Research Libraries, Chicago, Illinois. email to Marion Wallace The Friend newspaper, Orange Free State, South Africa

49. Carrington, C. E., (1955) The life of Rudyard Kipling, Doubleday & Co., Garden City, NY, p. 236

50. Kipling, Rudyard (18 March 1900). "Kipling at Cape Town: Severe Arraignment of Treacherous Afrikanders and Demand for Condign Punishment By and By" (PDF). The New York Times. p. 21.

51. "Kipling.s Sussex: The Elms". Kipling.org.

52. "Bateman's: Jacobean house, home of Rudyard Kipling". National Trust.org.

53. Carrington, C. E., (1955) The life of Rudyard Kipling, p. 286

54. "Bateman's House". Nationaltrust.org.uk. 17 November 2005. Archived from the original on 17 January 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

55. "Writers History – Kipling Rudyard". writershistory.com. Archived from the original on 25 April 2015.

56. Scott, pp. 318–319

57. Leoshko, J. (2001). "What is in Kim? Rudyard Kipling and Tibetan Buddhist Traditions". South Asia Research. 21 (1): 51–75.

58. Gilmour, p. 206

59. Bennett, Arnold (1917). Books and Persons Being Comments on a Past Epoch 1908–1911. London: Chatto & Windus.

60. Fred Lerner. "A Master of Our Art: Rudyard Kipling and modern Science Fiction". The Kipling Society.

61. Nomination Database. Nobelprize.org. Retrieved on 4 May 2017.

62. "Nobel Prize in Literature 1907 – presentation Speech". Nobelprize.org.

63. Emma Jones (1 October 2004). The Literary Companion. Robson. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-86105-798-3.

64. Jump up to:a b c MacKenzie, David & Dutil, Patrice (2011) Canada 1911: The Decisive Election that Shaped the Country. Toronto: Dundurn. p. 211. ISBN 1554889472.

65. Gilmour, p. 242

66. Gilmour, p. 243

67. Gilmour, p. 241

68. Gilmour, pp. 242–244

69. Gilmour, p. 244

70. Mackey, Albert G. (1946). Encyclopedia of Freemasonry, Vol. 1. Chicago: The Masonic History Co.

71. Our brother Rudyard Kipling. Masonic lecture. Albertpike.wordpress.com (7 October 2011). Retrieved on 4 May 2017.

72. "Official Visit to Meridian Lodge No. 687" (PDF). 12 February 2014.

73. Bilsing, Tracey (Summer 2000). "The Process of Manufacture of Rudyard Kipling's Private Propaganda" (PDF). War Literature and the Arts. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

74. Gilmour, p. 250.

75. J Gilmour, p. 251.

76. "Full text of "The new army in training"". archive.org.

77. Brown, Jonathan (28 August 2006). "The Great War and its aftermath: The son who haunted Kipling". The Independent. Retrieved 3 May2018. It was only his father's intervention that allowed John Kipling to serve on the Western Front - and the poet never got over his death.

78. Quinlan, Mark (11 December 2007). "The controversy over John Kipling's burial place". War Memorials Archive Blog. Retrieved 3 May2018.

79. "Solving the mystery of Rudyard Kipling's son". BBC News Magazine. 18 January 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

80. McGreevy, Ronan (25 September 2015). "Grave of Rudyard Kipling's son correctly named, says authority". The Irish Times. Retrieved 3 May2018.

81. "Casualty record: Lieutenant Kipling, John". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

82. Webb, George (1997). Foreword to: Kipling, Rudyard. The Irish Guards in the Great War. 2 vols. Spellmount. p. 9

83. Southam, Brian (6 March 2010). "Notes on "My Boy Jack"". Retrieved 23 July 2011.

84. "The Many Lovers of Miss Jane Austen", BBC2 broadcast, 9 pm 23 December 2011

85. The Fringes of the Fleet, Macmillan & Co., 1916

86. Original correspondence between Kipling and Maurice Hammoneau and his son Jean Hammoneau concerning the affair at the Library of Congress under the title: How "Kim" saved the life of a French soldier : a remarkable series of autograph letters of Rudyard Kipling, with the soldier's Croix de Guerre, 1918–1933. (LOC Ref#2007566938) [1]. The library also possesses the actual French 389-page paperback edition of Kim that saved Hammoneau's life, (LOC Ref 2007581430) [2]

87. Simmers, George (27 May 1918). "A Kipling Hoax". The Times.

88. Kipling, Rudyard (1923). The Irish Guards in the Great War. 2 vols. London.

89. Gilmour, p. 273.

90. Gilmour, pp. 273–274.

91. Hodgson, p. 1060.

92. "The Liberty League—a campaign against Bolshevism | Jot101". jot101.com. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

93. Miller, David and Dinan, William (2008) A Century of Spin. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-7453-2688-7

94. Gilmour, p. 275.

95. Kipling, Rudyard (1940) The Definitive edition of Rudyard Kipling's verse. Hodder & Stoughton.

96. "The day's work". Internet Archive.

97. "The Iron Ring". Ironring.ca. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

98. "The Calling of an Engineer". Ironring.ca. Retrieved 24 November2012.

99. Gilmour, p. 300.

100. Gilmour, pp. 300–301.

101. Gilmour, p. 293.

102. Gilmour, pp. 302, 304.

103. Hodgson, pp. 1059–1060.

104. Hodgson, pp. 1062–1063.

105. Hodgson, p. 1059.

106. Smith, Michael."Kipling and the Swastika". Kipling.org.

107. Schliemann, H, Troy and its remains, London: Murray, 1875, pp. 102, 119–20

108. Boxer, Sarah (29 June 2000). "One of the World's Great Symbols Strives for a Comeback". Think Tank. The New York Times. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

109. Rudyard Kipling, War Stories and Poems (Oxford Paperbacks, 1999), pp. xxiv–xxv

110. Knight, Sam (17 March 2017). "'London Bridge is down': the secret plan for the days after the Queen's death". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

111. Rose, Kenneth (1983). King George V. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 394. ISBN 978-1-84212-001-9.

112. Short Stories from the Strand, The Folio Society, 1992

113. Harry Ricketts (December 2000). Rudyard Kipling: A Life. Carroll & Graf. pp. 388–. ISBN 978-0-7867-0830-7. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

114. Rudyard Kipling's Waltzing Ghost: The Literary Heritage of Brown's Hotel, paragraph 11, Sandra Jackson-Opoku, Literary Traveler

115. Chernega, Carol (2011). "A Dream House: Exploring the Literary Homes of England". p. 90. Dog Ear Publishing. p. 90. ISBN 1457502461.

116. "History – Rudyard Kipling". Westminster abbey.org.

117. Article from the Red Orbit News network 16 March 2010. Retrieved 18 March 2010

118. "Rudyard Kipling inspires naming of prehistoric crocodile". BBC Online. 20 March 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

119. Flood, Alison (25 February 2013). "50 unseen Rudyard Kipling poems discovered". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

120. Jarrell, Randall (1999). "On Preparing to Read Kipling." No Other Book: Selected Essays. New York: HarperCollins.

121. The Indian Tales of Rudyard Kipling on IMDb

122. Eliot. Eliot's essay occupies 31 pages.

123. Eliot, p. 29.

124. Eliot, p. 22.

125. Eliot, p. 36.

126. Orwell, George (February 1942). "Rudyard Kipling". Horizon. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

127. Brackenbury, Alison. "Poetry Hero: Rudyard Kipling". Poetry News. The Poetry Society (Spring 2011). Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

128. Pareles, Jon (26 September 1991). "Peter Bellamy, 47; British Folk Singer Who Wrote Opera". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 July2014.

129. "Bastard King of England, The". fresnostate.edu.

130. “Keith Joseph Memorial Lecture ("Liberty and Limited Government")”. Margaret Thatcher.org. 1996 Jan 11.

131. "BBC Radio 4 – Rhyme and Reason, Billy Bragg". BBC.

132. WORLD VIEW: Is Afghanistan turning into another Vietnam?, Johnathan Power, The Citizen, 31 December 2010

133. Is America waxing or waning?, Andrew Sullivan, The Atlantic, 12 December 2010

134. Dufour, Steve. "Rudyard Kipling, official poet of the 911 War". 911poet.blogspot.com.

135. "History of Mowglis". Retrieved 26 November 2013.

136. "ScoutBase UK: The Library – Scouting history – Me Too! – The history of Cubbing in the United Kingdom 1916–present". Scoutbase.org.uk. Archived from the original on 25 November 2005. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

137. "History at Bateman's". National Trust. 22 February 2019.

138. Howard, Philip (19 September 1977) "University library to have Kipling papers". The Times", p.1

139. leader, Zachary (2007). The Life of Kingsley Amis. Vintage. pp. 704–705. ISBN 0375424989.

140. "Personal touch brings Kipling's Sussex home to life". The Argus.

141. "Rudyard Kipling Readings by Ralph Fiennes".Allmusic.

142. "History repeats itself, in stopping short". telegraphindia.com.

143. Subhash Chopra (2016). Kipling Sahib : the Raj patriot. London: New Millennium. ISBN 9781858454405.

144. Globalization and educational rights: an intercivilizational analysis, Joel H. Spring, pg.137

145. Post independence voices in South Asian writings, Malashri Lal, Alamgīr Hashmī, Victor J. Ramraj, 2001. (Not surprisingly, a brief biographical aside practically identifies Nehru with Kim)

146. Khushwant Singh, Review of The Book of Prayer by Renuka Narayanan , 2001

147. "When Malgudi man courted controversy". The Hindu. Retrieved 13 October 2014

148. Ahmed, Zubair (27 November 2007). "Kipling's India home to become museum". BBC News. Retrieved 9 August 2008.

Cited sources• Eliot, T.S. (1941). A Choice of Kipling's Verse, made by T. S. Eliot with an essay on Rudyard Kipling. Faber and Faber.

• Gilmour, David (11 June 2003). The long recessional : the imperial life of Rudyard Kipling. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 9781466830004.

• Hodgson, Katherine (October 1998). "The Poetry of Rudyard Kipling in Soviet Russia". The Modern Language Review. 93 (4): 1058–1071. JSTOR 3736277.

• Scott, David (June 2011). "Kipling, the Orient, and Orientals: "Orientalism" Reoriented?". Journal of World History. 22 (2): 299–328 (315). JSTOR 23011713.

Further reading

Biography and criticism• Allen, Charles (2007) Kipling Sahib: India and the Making of Rudyard Kipling, Abacus, 2007. ISBN 978-0-349-11685-3

• Bauer, Helen Pike (1994) Rudyard Kipling: A Study of the Short Fiction New York: Twayne

• Birkenhead, Lord (Frederick Smith, 2nd Earl of Birkenhead) (1978) Rudyard Kipling (Worthing: Littlehampton Book Services Ltd.) ISBN 978-0-297-77535-5

• Carrington, Charles (1955). Rudyard Kipling: His Life and Work. London: Macmillan & Co.

• David, C. (2007). Rudyard Kipling: a critical study, New Delhi, Anmol, 2007. ISBN 81-261-3101-2

• Dillingham, William B (2005) Rudyard Kipling: Hell and Heroism New York: Palgrave Macmillan

• Gilbert, Elliot L. ed., (1965) Kipling and the Critics (New York: New York University Press)

• Gilmour, David. (2003) The Long Recessional: The Imperial Life of Rudyard Kipling New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-52896-9

• Green, Roger Lancelyn, ed., (1971) Kipling: the Critical Heritage (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul).

• Gross, John, ed. (1972) Rudyard Kipling: the Man, his Work and his World (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson)

• Harris, Brian (2014) "The Surprising Mr Kipling: An anthology and reassessment of the poetry of Rudyard Kipling (CreateSpace) ISBN 978-1-4942-2194-2

• Harris, Brian (2015) "The Two Sided Man" (CreateSpace) ISBN 1508712328.

• Kemp, Sandra. (1988) Kipling's Hidden Narratives Oxford: Blackwell

• Lycett, Andrew (1999). Rudyard Kipling. London, Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-81907-0

• Lycett, Andrew (ed.) (2010). Kipling Abroad, I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84885-072-9

• Mallett, Phillip (2003) Rudyard Kipling: A Literary Life Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

• Montefiore, Jan (ed.) (2013) In Time's Eye: Essays on Rudyard Kipling Manchester: Manchester University Press

• Narita, Tatsushi. T. S. Eliot and his Youth as 'A Literary Columbus'. Nagoya: Kougaku Shuppan, 2011

• Nicolson, Adam (2001) Carrie Kipling 1862–1939 : The Hated Wife. Faber & Faber, London. ISBN 0-571-20835-5

• Ricketts, Harry. (2001) Rudyard Kipling: A Life New York: Da Capo Press ISBN 0-7867-0830-1

• Rooney, Caroline, and Kaori Nagai, eds. Kipling and Beyond: Patriotism, Globalisation, and Postcolonialism (Palgrave Macmillan; 2011) 214 pages; scholarly essays on Kipling's "boy heroes of empire," Kipling and C.L.R. James, and Kipling and the new American empire, etc.

• Rutherford, Andrew, ed. (1964) Kipling's Mind and Art (Edinburgh and London: Oliver and Boyd)

• Sergeant, David, (2013) Kipling's Art of Fiction 1884–1901 (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

• Martin Seymour-Smith, Rudyard Kipling, (1990).

• Shippey, Tom, "Rudyard Kipling," in: Cahier Calin: Makers of the Middle Ages. Essays in Honor of William Calin, ed. Richard Utz and Elizabeth Emery (Kalamazoo, MI: Studies in Medievalism, 2011), pp. 21–23.

• Tompkins, J. M. S. (1959) The Art of Rudyard Kipling (London : Methuen) online edition

• Walsh, Sue (2010) Kipling's Children's Literature: Language, Identity, and Constructions of Childhood Farnham: Ashgate

• Wilson, Angus The Strange Ride of Rudyard Kipling: His Life and Works New York: The Viking Press, 1978. ISBN 0-670-67701-9

External links• Wikilivres has original media or text related to this article: Rudyard Kipling (in the public domain in New Zealand)

• The Kipling Society website

Other information

Works• Works by Rudyard Kipling at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about Rudyard Kipling at Internet Archive

• Works by Rudyard Kipling at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

• Works by Rudyard Kipling (not public domain in USA, so not available on Wikisource)

Resources• The Rudyard Kipling Collection maintained by Marlboro College.

• The Rudyard Kipling Poems by Poemist.

• Rudyard Kipling: The Books I Leave Behind exhibition, related podcast, and digital images maintained by the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University

• Rudyard Kipling at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

• The Rudyard Kipling Collections From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress

• Archival material at Leeds University Library

• Newspaper clippings about Rudyard Kipling in the 20th Century Press Archives of the German National Library of Economics