India Houseby Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/26/19

-- Fort William-India House Correspondence, and Other Contemporary Papers Relating Thereto, Vol. I: 1748-1756, edited by K. K. Datta, M.A., Ph.D.-- History of the Province of Behar, From "The History, Antiquities, Topography, and Statistics of Eastern India; Surveyed Under the Orders of the Supreme Government and Collated from the Original Documents at the East India House, With the Permission of the Honourable Court of Directors, by Montgomery Martin

Clockwise from top left: Dhingra, Aiyar, Savarkar, Bapat, Gonne, Acharya, Kanhere and Pillai.

Clockwise from top left: Dhingra, Aiyar, Savarkar, Bapat, Gonne, Acharya, Kanhere and Pillai.

Centre: The Indian Sociologist, September 1908 issue.India House was a student residence that existed between 1905 and 1910 at Cromwell Avenue in Highgate, North London. With the patronage of lawyer Shyamji Krishna Varma, it was opened to promote nationalist views among Indian students in Britain. This institute used to grant scholarships to Indian youths for higher studies in England. The building rapidly became a hub for political activism, one of the most prominent for overseas revolutionary Indian nationalism. "India House" came to informally refer to the nationalist organisations that used the building at various times.Patrons of India House published an anti-colonialist newspaper, The Indian Sociologist, which the British Raj banned as "seditious".[1] A number of prominent Indian revolutionaries and nationalists were associated with India House, including Vinayak Damodar Savarkar,

Bhikaji Cama, V.N. Chatterjee, Lala Har Dayal, V.V.S. Aiyar, M.P.T. Acharya and P.M. Bapat.

In 1909, a member of India House, Madan Lal Dhingra, assassinated Sir W.H. Curzon Wyllie, political aide-de-camp to the Secretary of State for India.

The investigations by Scotland Yard and the Indian Political Intelligence Office that followed the assassination sent the organisation into decline. A crackdown on India House activities by the Metropolitan Police prompted a number of its members to leave Britain for France, Germany and the United States. Many members of the house were involved in revolutionary conspiracies in India. The network created by India House played a key part in the Hindu–German Conspiracy for nationalist revolution in India during World War I. In the coming decades, India House alumni went on to playing a leading role in the founding of Indian communism and Hindu nationalism.BackgroundThe consolidation of the British East India Company's rule in the Indian subcontinent during the 18th century brought about socio-economic changes which led to the rise of an Indian middle class and steadily eroded pre-colonial socio-religious institutions and barriers.[2] The emerging economic and financial power of Indian business-owners and merchants and the professional class brought them increasingly into conflict with the British Raj. A rising political consciousness among the native Indian social elite (including lawyers, doctors, university graduates, government officials and similar groups) spawned an Indian identity[3][4] and fed a growing nationalist sentiment in India in the last decades of the nineteenth century.[5]

The creation in 1885 of the Indian National Congress in India by the political reformer A.O. Hume intensified the process by providing an important platform from which demands could be made for political liberalisation, increased autonomy, and social reform.[6]

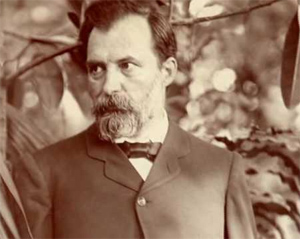

Allan Octavian Hume, CB ICS (4 June 1829 – 31 July 1912[1]) was a member of the Imperial Civil Service (later the Indian Civil Service), a political reformer, ornithologist and botanist who worked in British India. He was one of the founders of the Indian National Congress. A notable ornithologist, Hume has been called "the Father of Indian Ornithology" and, by those who found him dogmatic, "the Pope of Indian ornithology".[2]

As an administrator of Etawah, he saw the Indian Rebellion of 1857 as a result of misgovernance and made great efforts to improve the lives of the common people. The district of Etawah was among the first to be returned to normality and over the next few years Hume's reforms led to the district being considered a model of development. Hume rose in the ranks of the Indian Civil Service but like his father Joseph Hume, the radical MP, he was bold and outspoken in questioning British policies in India. He rose in 1871 to the position of secretary to the Department of Revenue, Agriculture, and Commerce under Lord Mayo. His criticism of Lord Lytton however led to his removal from the Secretariat in 1879....

He was briefly a follower of the theosophical movement founded by Madame Blavatsky. He left India in 1894 to live in London from where he continued to take an interest in the Indian National Congress, apart from taking an interest in botany and founding the South London Botanical Institute towards the end of his life.

-- Allan Octavian Hume, by Wikipedia

The leaders of the Congress advocated dialogue and debate with the Raj administration to achieve their political goals. Distinct from these moderate voices (or loyalists) who did not preach or support violence was the nationalist movement, which grew particularly strong, radical and violent in Bengal and in Punjab. Notable, if smaller, movements also appeared in Maharashtra, Madras and other areas across the south.[6] The controversial 1905 partition of Bengal escalated the growing unrest, stimulating radical nationalist sentiments and becoming a driving force for Indian revolutionaries.[7]

From its inception, the Congress had also sought to shape public opinion in Britain in favour of Indian political autonomy.[6][8] The Congress's British Committee, established in 1889, published a periodical called India which featured moderate, loyalist opinion and provided information about India tailored to a British readership.[9]

The committee was successful in calling the British public's attention to issues of civil liberties in India, but it largely failed to bring about political change, prompting socialists such as Henry Hyndman to advocate a more radical approach.[10] In 1893 an "Indian committee" was established in the British Parliament as a pressure group to influence policy directly,[10][11][12] but it grew increasingly distant from an emerging movement which advocated absolute Indian self-governance. Nationalist leaders in India (such as Bipin Chandra Pal, who led the agitation against the Bengal partition) and Indian students in Britain criticised the committee for what they perceived as its overcautious approach.[8][11] Against this background, coincident with the political upheaval caused by the 1905 partition of Bengal, a nationalist lawyer named Shyamji Krishna Varma founded India House in London.[13]

India HouseIndia House is a large Victorian Mansion at 65 Cromwell Avenue, Highgate, North London. It was inaugurated on 1 July 1905 by Henry Hyndman in a ceremony attended by, among others, Dadabhai Naoroji, Charlotte Despard and Bhikaji Cama[14] When opened as a student-hostel in 1905, it provided accommodation for up to thirty students.[15] In addition to being a student-hostel, the mansion also served as the headquarters for several organisations, the first of which was the Indian Home Rule Society (IHRS).

Indian Home Rule Society Bhikaji Cama with the Stuttgart flag, 1907. A number of India House members attended the socialist conference that year, and Cama herself worked closely with Krishna Varma.Krishna Varma

Bhikaji Cama with the Stuttgart flag, 1907. A number of India House members attended the socialist conference that year, and Cama herself worked closely with Krishna Varma.Krishna Varma admired Swami Dayananda Saraswati's cultural nationalism and believed in Herbert Spencer's dictum that "Resistance to aggression is not simply justified, but imperative".[16]

A graduate of Balliol College, Oxford, he returned to India in the 1880s and served as divan (administrator) of a number of princely states, including Ratlam and Junagadh. He preferred this position to working under what he considered the alien rule of Britain.[16] However,

a supposed conspiracy of local British officials at Junagadh, compounded by differences between Crown authority and British Political Residents regarding the states, led to Varma's dismissal.[17] He returned to England, where he found freedom of expression more favourable. Varma's views were staunchly anti-colonial, extending even to support for the Boers during the Second Boer War in 1899.[16]

Krishna Varma co-founded the IHRS in February 1905,[18] with Bhikaji Cama, S.R. Rana, Lala Lajpat Rai and others,[11][19][20] as a rival organisation to the British Committee of the Congress.[21] Subsequently, Krishna Varma used his considerable financial resources to offer scholarships to Indian students in memory of leaders of the 1857 uprising, on the condition that the recipients would not accept any paid post or honorary office from the British Raj upon their return home.[16] These scholarships were complemented by three endowments of 2000 Rupees courtesy S.R. Rana, in memory of Rana Pratap Singh.[22] Open to "Indians only", the IHRS garnered significant support from Indians – especially students – living in Britain. Funds received by Indian students as scholarships and bursaries from universities also found their way to the organisation. Following the model of Victorian public institutions,[23] the IHRS adopted a constitution. The aim of the IHRS, clearly articulated in this constitution, was to "secure Home Rule for India, and to carry on a genuine Indian propaganda in this country by all practicable means".[24] It recruited young Indian activists, raised funds, and possibly collected arms and maintained contact with revolutionary movements in India.[8][25] The group professed support for causes in sympathy with its own, such as Turkish, Egyptian and Irish republican nationalism.[19]

The Paris Indian Society, a branch of the IHRS, was launched in 1905 under the patronage of Bhikaji Cama, Sardar Singh Rana and B.H. Godrej.[26] A number of India House members who later rose to prominence – including V.N. Chatterjee, Har Dayal and Acharya and others – first encountered the IHRS through this Paris Indian Society.[27]

Cama herself was at this time deeply involved with the Indian revolutionary cause, and she nurtured close links with both French and exiled Russian socialists.[28][29] Lenin's views are thought to have influenced Cama's works at this time, and Lenin is believed to have visited India House during one of his stays in London.[30][31] In 1907, Cama, along with V.N. Chatterjee and S.R. Rana, attended the Socialist Congress of the Second International in Stuttgart. There, supported by Henry Hyndman, she demanded recognition of self-rule for India and in a famous gesture unfurled one of the first Flags of India.[32]The Indian Sociologist August 1909 issue of The Indian Sociologist. Guy Aldred was prosecuted for his comments in this issue purportedly supporting Dhingra and supporting anti-colonial anarchism.

August 1909 issue of The Indian Sociologist. Guy Aldred was prosecuted for his comments in this issue purportedly supporting Dhingra and supporting anti-colonial anarchism.In 1904, Krishna Varma founded The Indian Sociologist (TIS), a penny monthly (with Spencer's dictum as its motto),[16] as a challenge to the British Committee's Indian.[8] The title of the publication was intended to convey Krishna Varma's conviction that the ideological basis of Indian independence from Britain was to the discipline of sociology.[33] TIS was critical of the moderate loyalist approach and its appeal to British liberalism, exemplified by the work of Indian leader G.K. Ghokale; instead, TIS advocated Indian self-rule. It was critical of the British Committee, whose members – being mostly from the Indian Civil Service – were in Krishna Varma's view complicit in exploitation of India.[8] TIS quoted extensively from the works of British writers, which Krishna Varma interpreted to explain his views that the Raj was colonial exploitation, and that the Indians had a right to oppose it, by violence if necessary.[8] It advocated confrontation and demands rather than petition and accommodation.[34] However, Krishna Varma's views and justifications of political violence in nationalist struggle were still cautious, considering violence as a last resort. His support was initially intellectual, and he was not actively involved in planning revolutionary violence.[35] Freedom of the press and the liberal approach of the British establishment meant Krishna Varma could air views that would have been rapidly suppressed in India.[8]

The views expressed in TIS drew criticisms from ex-Indian civil servants in the British press and Parliament. Highlighting Krishna Varma's citation of British writers and lack of reference to Indian tradition or values, they argued that he was disconnected from the Indian situation and Indian feelings, and was intellectually dependent on Britain.[36] Valentine Chirol, foreign editor of The Times, who had close associations with the Raj, accused Krishna Varma of preaching "disloyal sentiments" to Indian students, and demanded he be prosecuted.[37][38] Chirol later described India House as "the most dangerous organisation outside India".[10][39] Krishna Varma and TIS also drew the attention of King Edward VII. Greatly concerned, the King asked John Morley, the Secretary of State for India, to stop the publication of such messages.[40] Morley refused to take any action contrary to his liberal political principles, but Chirol's tirade against TIS and Krishna Varma forced the Government to investigate.[35] Detectives visited India House and interviewed the printers of its publication. Krishna Varma saw these actions as the start of a crackdown on his work and, fearing arrest, moved to Paris in 1907; he never returned to Britain.[37][17]

SavarkarSee also: V.N. Chatterjee, V.V.S. Aiyar, and Hind Swaraj

After Krishna Varma's departure, the organisation found a new leader in Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, a law student who had first arrived in London in 1906 on scholarship from Krishna Varma. Savarkar was an admirer of the Italian nationalist philosopher Giuseppe Mazzini and a protégé of the Indian Congress leader, Bal Gangadhar Tilak.[36][41][42] He was associated with the nationalist movement in India, having founded the Abhinav Bharat Society (Young India Society) in 1906 while studying at Fergusson College in Pune (these links put him in contact with the still largely unknown Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi.[36][43][44]) In London, Savarkar's fiery nationalist views had at first alienated the residents of India House, most significantly V.V.S. Aiyar. Over time, however, he became a central figure in the organisation.[45] He devoted his efforts to writing nationalist material, organising public meetings and demonstrations,[19] and establishing branches of Abhinav Bharat in the country.[46] [b]He kept in touch with B.G. Tilak in India, to whom he passed on manuals on bomb-making.[47]

Impressed and influenced by the Italian wars of Independence, Savarkar believed in an armed revolution in India and was prepared to seek assistance from Germany toward this end. He proposed the indoctrination of Indian soldiery in the British army, just as the Young Italy movement had indoctrinated Italians serving in the Austrian forces.[48] In London, Savarkar founded the Free India Society (FIS), and in December 1906 he opened a branch of Abhinav Bharat.[49][50] This organisation drew a number of radical Indian students, including P.M. Bapat, V.V.S. Aiyar, Madanlal Dhingra, and V.N. Chatterjee.[51] Savarkar had lived in Paris for some time, and frequently visited the city after moving to London.[42] By 1908, he had recruited to the organisation a number of Indian businessmen residing in Paris. During one visit, Savarkar met Gandhi again when the latter visited India House in 1906 and 1909, and his hardline views may have influenced Gandhi's opinion on nationalist violence.[52]

TransformationSee also: M. P. T. Acharya

India House, which now housed the Abhinav Bharat Society and its relatively peaceful front the Free India Society, rapidly developed into a radical meeting ground quite different from the IHRS. Unlike the latter, it became wholly self-reliant with regard to finances and organisation, and it developed independent nationalist ideologies that moved away from European philosophies.

Under Savarkar's influence, it drew inspiration from past Indian revolutionary movements, religious scriptures (including the Bhagavad Gita), and Savarkar's own studies in Indian history, including The Indian War of Independence.[23] Savarkar translated Giuseppe Mazzini's autobiography into Marathi and extolled the virtues of secret societies.[38] India House today. A blue plaque commemorates Savarkar's stay during its turbulent history.

India House today. A blue plaque commemorates Savarkar's stay during its turbulent history.India House was soon transformed into the headquarters of the Indian revolutionary movement in Britain.[15] Its newest members were young men and women in London who came from all over India.[53] A large number, each comprising about a quarter of the total membership, were from Bengal and Punjab, while a significant but smaller group came from Bombay and Maharashtra.[53] The Free India Society had a semi-religious oath of initiation, and served as a cover for the Abhinav Bharat Society's meetings.[51] The members were predominantly Hindus. Most were students in their mid-twenties, and usually belonged to the Indian social elite, from families of millionaires, mill owners, lawyers and doctors.

Nearly seventy people, including several women, regularly attended the Sunday evening meetings at which Savarkar gave lectures on topics ranging from the philosophy of revolution to bomb-making and assassination techniques.[15] Only a small proportion of these recruits to the society were known to have previously engaged in political activity or the Swadeshi movement in India.[53]

]b]Abhinav Bharat Society had two goals: to create through propaganda in Europe and North America an Indian public opinion in favour of nationalist revolution, and to raise funds, knowledge and supplies to carry out such a revolution.[/b][54] It emphasised actions of self-sacrifice by its members for the Indian cause. These were revolutionary activities which the masses could emulate, but which did not require a mass movement.[53]

The outbuilding of India House was converted to a "war workshop" where chemistry students attempted to produce explosives and manufacture bombs, while the printing press turned out "seditious" literature, including bomb-making manuals and pamphlets promoting violence toward Europeans in India. In the house was an arsenal of small arms that were intermittently dispatched to India through different avenues.[15] Savarkar was at the heart of these, spending a great deal of time in the explosives workshop and emerging on some evenings, according to a fellow revolutionary, "with telltale yellow stains of picric acid on his hands".[55] The residents of India House and members of Abhinav Bharat practiced shooting at a range in Tottenham Court Road in central London, and rehearsed assassinations they planned to carry out.[55]

The deliveries of weapons to India included, among others, a number of Browning pistols smuggled by Chaturbhuj Amin, Chanjeri Rao, and V. V. S. Aiyar when they returned to India.[56] Revolutionary literature was shipped under false covers and from different addresses to prevent detection by Indian postal authorities.[55] Savarkar's The Indian War of Independence was published (in 1909) and was considered inflammatory enough to be removed from the catalogue of the British Library to prevent Indian students from accessing it.[57] Sometime in 1908, India House acquired a manual for making bombs. Some suggest Savarkar acquired this in the French capital from a bomb manual given to Hemchandra Das – a Bengali revolutionary of the Anushilan Samiti – by a Russian revolutionary in Paris by the name of Nicholas Safranski.[58] Others opine that it was acquired through Russian revolutionaries in Paris by Bapat.[59] Bapat was declared absconder (a fugitive) in the Alipore bomb case of 1909, which followed the attempt to bomb a district magistrate's carriage in Bengal by Khudiram Bose.[60]

By 1908, the popularity of the India House group had overtaken the London Indian Society (LIS), established in 1865 by Dadabhai Naoroji and until then the largest association of Indians in London. Subsequently, India House took over the control of LIS when, at the annual general meeting that year, members of India House packed the gathering and ousted the old guard of the society.[61]CulminationSee also: Madan Lal Dhingra

Cover of the Paris Bande Mataram following Madanlal Dhingra's execution in August 1909. The Paris Indian Society replaced India House as the hotbed of seditious activities in the continent after 1909.

Cover of the Paris Bande Mataram following Madanlal Dhingra's execution in August 1909. The Paris Indian Society replaced India House as the hotbed of seditious activities in the continent after 1909.The activities of India House did not go unnoticed. In addition to questions raised in official Indian and British circles, Savarkar's unrestrained views had been published in English newspapers including the Daily Mail, Manchester Guardian and Dispatch.

By 1909, India House was under surveillance from Scotland Yard and Indian intelligence, and its activities were considerably curtailed.[62] Savarkar's elder brother Ganesh was arrested in India in June of that year, and was tried and exiled to the penal colony in the Andamans for publication of seditionist literature.[63]

Savarkar's speeches grew increasingly strident and called for revolution, widespread violence, and murder of all Englishmen in India.[63] The culmination of these events was the assassination of Sir William H. Curzon Wyllie, the political aide-de-camp to the Secretary of State for India, by Madanlal Dhingra on the evening of 1 July 1909, at a meeting of Indian students in the Imperial Institute in London.[63] Dhingra was arrested and later tried and executed.

In the aftermath of the assassination, India House was rapidly shut down. Investigations into the killing were expanded to look for broader conspiracies originating from India House; although Scotland Yard stated that none existed, Indian intelligence sources suggested otherwise.[64] These sources further suggested that Dhingra's intended target was John Morley, the Secretary of State for India himself. Savarkar possessed a copy of a written political statement by Dhingra which was confiscated at the latter's arrest. Its existence was denied by police, but through Irish sympathiser David Garnett Savarkar had this published in the Daily News on the day Dhingra was sentenced to death.[65] A number of sources suggested the assassination was in fact Savarkar's idea, and that he planned further action in Britain as well as India.[64] In March 1910, Savarkar was arrested upon his return to London from Paris and later deported to India.[66] While he was held at Brixton Prison during the deportation hearing, an attempt was made in May 1910 by the remnant of India House to storm his prison van and free him. This plot was coordinated with help from Irish republicans led by Maud Gonne. However, the plan failed when the ambush stormed an empty decoy van while Savarkar was transported along a different route.[67]

In the following year, police and political sources brought pressure on the residents of India House to leave England. While some of its leaders like Krishna Varma had already fled to Europe, others like Chattopadhyaya moved to Germany. Many others moved to Paris.[68] With the influence and work of a large number of nationalist students moving to the city, the Paris Indian Society gradually took India House's place as the centre of Indian nationalism on the continent.[69]CountermeasuresAlthough India House had stated its goals in The Indian Sociologist, the threat arising from the organisation was initially not considered serious by either Indian intelligence or British Special Branch.[57][70] This was compounded by a lack of clarity and communication from the Department of Criminal Intelligence operating in India under Charles Cleveland, and Scotland Yard's Special Branch.[57] Lack of direction and information from Indian political intelligence, compounded by Lord Morley's reluctance to engage in postal censorship,[71] led to Special Branch underestimating the threat.[71]

Scotland YardIn spite of these problems, and although Special Branch was wholly inexperienced in dealing with political crime,[70] the first observations of India House by Scotland Yard began as early as 1905. Detectives attended Sunday meetings at India House in May 1907, where they gained access to seditious literature.[71] The appearance of one agent, disguised as an Irish-American by the name of O'Brien, convinced Krishna Varma of the need to decamp to Paris.[71] In June 1908, concrete plans for cooperation between Indian and British police were arranged between India Office and Scotland Yard; the decision was made to place an ex-Indian policeman in charge of surveillance of India House.[72]

The arrival of B.C. Pal and G.S. Khaparde in London in 1908 further stirred the matter, since both were known to have been radical nationalist politicians in India. By September 1908, an agent had been installed within India House who was able to invite detectives to the Sunday night meetings of the Free India Society (attendance for Europeans was by invitation only).[72] The agent passed on some additional information, but was not able to infiltrate Savarkar's inner circle. Savarkar himself did not come under special scrutiny as a dangerous suspect until November 1909, when the agent delivered information about discussions of assassinations at Indian House. The agent may have been a young Maharashtrian by the name of Kirtikar, who had arrived at India House as an acquaintance of V.V.S. Aiyar, ostensibly to study dentistry in London. Kirtikar was discovered after Aiyar made enquiries at the London Hospital where he was supposed to be training, and was one night forced by Savarkar to confess at gun-point.[73]

After this incident, Kirtikar's reports were probably screened by Savarkar before they were passed on to Scotland Yard. M.P.T. Acharya was at this time instructed by Aiyar and Savarkar to set himself up as an informer to Scotland Yard; they believed this would provide information to the police and help corroborate the reports sent by Kirtikar.[45] Although it pursued Indian students and shadowed them closely, Scotland Yard was severely criticised for its inability to penetrate the organisation. The Viceroy's secretary, William Lee-Warner, was assaulted twice in London: he was slapped in the face in his office by a young Bengali student named Kunjalal Bhattacharji and assaulted in a London park by another Indian student. The Yard's inefficiency was blamed for these events.[72]

Department of Criminal IntelligenceUnknown to Scotland Yard,[74] by the beginning of 1909 the Indian Department of Criminal Intelligence (DCI) had made covert efforts of its own to infiltrate India House, with more success. An agent named "C" had been residing in India House for nearly a year; after convincing the residents that he was a genuine patriot, he began reporting back to India.[74][75] Possible reasons why DCI did not inform the Yard include a wish not to interfere with London investigations, a desire to maintain control over "C", and a fear of being accused of "deviousness" by the Yard.[74]

However, the DCI agent's first reports in early 1909 were of little value. Only in the months immediately preceding the Curzon Wyllie assassination did they prove useful. In June, the agent described the shooting practice at Tottenham Court range and rifle practice in the back of India House. This was followed by reports of Savarkar and V.V.S. Aiyar (who was considered his lieutenant) advising M.P.T. Acharya on acts of martyrdom.[74] Following the arrest and subsequent transportation of Savarkar's elder brother Ganesh in India on 9 June 1909,[63] C reported increasing ferocity and calls for vengeance in Savarkar's speeches.[63][74] In the following weeks, Savarkar was barred from joining the bar due to his political activity.[64] These were the events leading up to the assassination of Sir Curzon Wyllie. Although it was believed that Savarkar may have personally instructed or trained Dhingra, Metropolitan police were unable to bring a prosecution against the former since he had an alibi for the night.[76]

Indian Special BranchIn the aftermath of Curzon Wyllie's assassination, Metropolitan Police Special Branch was reorganised in July 1909 following a meeting between India Office and the Commissioner of Police Sir Edward Henry. This led to the opening of an Indian Special Branch with a staff of 38 officers by the end of July.[77] It received considerable resources during the investigation of Curzon Wyllie's assassination, and satisfied the demands of Indian Criminal Intelligence with regard to monitoring the Indian seditionist movement in Britain.[77]

The police brought strong pressure on India House and began gathering intelligence on Indian students in London. These, along with threats to their careers, robbed India House of its student support base. It slowly began to disassemble as a centre of radical Indian Nationalism. As Thirumal Acharya described bitterly, the residence was treated akin to a "leper's home" by the Indian students in the city.[78] In addition, although student political activism could not be curtailed too heavily for fear of accusations of repression, the British Government successfully implemented laws to curtail the publication and distribution of nationalist or seditious material from Britain. Among these was Bipin Pal's Swaraj, which was forced to close, an event which ultimately drove Pal to penury and mental collapse in London.[78] India House ceased to be an influence in Britain.[79]

InfluencePolitical activities at India House were chiefly aimed at young Indians, especially students, in Britain. Political discontent was at the time growing steadily among this group, especially those in touch with the professional class in India and those studying in depth the philosophies of European liberalism.[80] Their discontent was noted among British academic and political circles quite early on, with some voicing fear that these students would take refuge in extremist politics.[80]

Nationalist movementSee also: A.M.T. Jackson, Anant Kanhere, Anushilan Samiti, and Hind Swaraj

A committee set up in 1907 under Sir William Lee-Warner to investigate political unrest among Indian students in Britain noted the strong influence that India House had on this group.[81][82] This was while India House was under the stewardship of Shyamji Krishna Varma.[83] Indian students who discussed the community at the time described the growing influence of India House – especially in the context of the 1905 partition of Bengal – and attributed to this influence the decrease in the number of Indian applicants for Government posts and the Indian Civil Service. The Indian Sociologist attracted considerable attention in London newspapers.[84] Others, however, disagreed with these views and described India House's appeal as limited. S.D. Bhaba, president of the Indian Christian Union, once described Krishna Varma as a man "whose bark was worse than his bite".[84]

Under Savarkar, the organisation became the focus of the Indian revolutionary movement abroad and one of the most important links between revolutionary violence in India and Britain.[63][66][76] Although the organisation welcomed both moderates and those with extremist views, the former outnumbered the latter.[84] Significantly, a number of the residents, especially those who agreed with Savarkar's views, did not have any history of participation in nationalist movements in India, suggesting they were indoctrinated during their stay at India House.[53]

More significantly, India House was a source of arms and seditious literature that was rapidly distributed in India. In addition to The Indian Sociologist, pamphlets like Bande Mataram and Oh Martyrs! by Savarkar extolled revolutionary violence. Direct influences and incitement from India House were noted in several incidents of political violence, including assassinations, in India at the time.[49][57][85] One of the two charges against Savarkar during his trial in Bombay was for abetting the murder of the District Magistrate of Nasik, A.M.T. Jackson, by Anant Kanhere in December 1909. The arms used were directly traced through an Italian courier to India House. Ex-India House residents M.P.T. Acharya and V.V.S. Aiyar were noted in the Rowlatt report to have aided and influenced political assassinations, including the murder of Robert D'Escourt Ashe at the hands of Vanchi Iyer.[49] The Paris-Safranski link was strongly suggested by French police to be involved in the 1907 attempt in Bengal to derail the train carrying the Lieutenant-Governor Sir Andrew Fraser.[86] The activities of nationalists abroad is believed to have shaken the loyalty of a number of native regiments of the British Indian Army.[87] The assassination of Curzon Wyllie was highly publcised.[88] The symbolic impact of Dhingra's actions on the colonial authorities and on the Indian revolutionary movement was profound at the time.[89] The British empire had never been targeted in its own metropolis.[88] Dhingra's last statement is said to have earned the admiration of Winston Churchill, who described it as the finest ever made in the name of Patriotism.[88]

India House and its activities had some influence on the subsequent nonviolent philosophy adopted by Gandhi.[52] He had met some members of India House, including Savarkar, in London as well as in India, and disagreed with the adoption of nationalist and political philosophies from the west. Gandhi dismissively labelled this revolutionary violence as anarchist and its practitioners as "The Modernists".[52] Some of his subsequent writings, including Hind Swaraj, were opposed to the activities of Savarkar and Dhingra, and disputed the argument that violence was innocent if perpetrated under a nationalist identity or while under Colonial victimhood.[52]

It was against this strategy of revolutionary violence – and in recognition of its consequences – that the formative background of Gandhian nonviolence was framed.[52]India Houses abroadSee also: Har Dayal, Mohammed Barkatullah, Taraknath Das, and Ghadar party

Following the example laid by the original India House, India Houses were opened in the United States and in Japan.[90] Krishna Varma had built close contacts with the Irish Republican movement. As a result, articles from The Indian Sociologist were reprinted in the United States in the Gaelic American. In addition, with the efforts of the growing Indian student population, other organisations mirroring India House emerged. The first of these was the Pan-Aryan Association, modelled after the Indian Home Rule Society, opened in 1906 through the joint Indo-Irish efforts of Mohammed Barkatullah, S.L. Joshi and George Freeman.[1] Barkatullah himself had been closely associated with Krishna Varma during his earlier stay in London, and his subsequent career in Japan put Barkatullah at the heart of Indian political activities there.[1]

The American branch also invited Bhikaji Cama – who at the time was close to the works of Krishna Varma – to give a series of lectures in the United States.

An India House, though not officially allied to the London organisation, was founded in Manhattan in New York in January 1908 with funds from a wealthy lawyer of Irish descent named Myron Phelps. Phelps admired Swami Vivekananda, and the Vedanta Society (established by the Swami) in New York was at the time under Swami Abhedananda, who was considered "seditionist" by the British.[90] In New York, Indian students and ex-residents of London India House took advantage of liberal press laws to circulate The Indian Sociologist and other nationalist literature.[90] New York increasingly became an important centre for the global Indian movement; Free Hindustan, a political revolutionary journal published by Taraknath Das, closely mirroring The Indian Sociologist, moved from Vancouver and Seattle to New York in 1908. Das collaborated extensively with the Gaelic American with help from George Freeman before Free Hindustan was proscribed in 1910 under British diplomatic pressure.[91] After 1910, the American east coast activities began to decline and gradually shifted to San Francisco. The arrival of Har Dayal around this time bridged the gap between the intellectual agitators and the predominantly Punjabi labour workers and migrants, laying the foundations of the Ghadar movement.[91]

An India House was opened in Tokyo in 1907.[92] The city – like London and New York – had by the end of the 19th century a steadily growing Indian student population, with whom Krishna Varma kept in close contact. However, Krishna Varma was initially concerned about spreading his resources too thin, especially since the Japanese centre lacked a strong leadership. He further feared interference from Japan, which was on friendly terms with Britain.[92] Nonetheless, the presence of revolutionaries from Bengal and close correspondence between the London and Tokyo houses allowed the latter to gain prominence in The Indian Sociologist. The India House in Tokyo was a residence for sixteen Indian students in 1908; it accepted students from other Asian countries including Ceylon, aiming to build a broad foundation for Indian nationalism based on pan-Asiatic values. The movement gained new momentum after Barkatullah, on the advice of Krishna Varma and George Freeman, moved from New York to Tokyo in 1909.[92]

Taking up the post of Professor of Urdu at Tokyo University, Barkatullah was responsible for East Asian distribution of The Indian Sociologist and other nationalist literature from London. His work at the time also included the publication of Islamic Fraternity, which was financed by the Ottoman Empire. Barkatullah transformed it into an anti-British mouthpiece, invited contributions from Krishna Varma, and advocated Hindu–Muslim unity in India.[93] He published other nationalist pamphlets which found their way to the Pacific coast and East Asian settlements. Further, Barkatullah established links with prominent Japanese politicians including Okawa Shumei, whom he won over to the Indian cause.[93] British CID, concerned about the threat that Barkatullah's work posed to the empire, exerted diplomatic pressure to have Islamic Fraternity closed down in 1912. Barkatullah was denied tenure and was forced to leave Japan in 1914.[93]World War ISee also: Intelligence Bureau for the East

Ghadar di gunj, an early Ghadarite compilation of nationalist and socialist literature, was banned in India in 1913. The Ghadrite movement was involved in the Hindu–German Conspiracy during WWI.

Ghadar di gunj, an early Ghadarite compilation of nationalist and socialist literature, was banned in India in 1913. The Ghadrite movement was involved in the Hindu–German Conspiracy during WWI.Following the liquidation of India House in 1909 and 1910, its members gradually dispersed to different countries in Europe, including France and Germany, as well as the United States.

The network founded at India House was to be key in the efforts by the Indian revolutionary movement against the British Raj through World War I. During the war, the Berlin Committee in Germany, the Ghadar Party in North America, and the Indian revolutionary underground attempted to transport men and arms from United States and East Asia into India, intended for a revolution and mutiny in the British Indian Army. During the conspiracy, the revolutionaries collaborated extensively with the Irish Republican Brotherhood, Sinn Féin, Japanese patriotic societies, Ottoman Turkey and, most prominently, the German Foreign Office. The conspiracy has since been called The Hindu–German Conspiracy.[94][95] Among other efforts, the alliance attempted to rally Afghanistan against British India.[96][/b]

A number of failed mutinies erupted in India in 1914 and 1915, of which the Ghadar Conspiracy, the Singapore Mutiny, and the Christmas Day Plot were the most notable. The threat posed by the conspiracy was key in the passage of the Defence of India Act 1915, and suppression of the movement necessitated an international counter-intelligence operation on the part of the British empire lasting nearly ten years.[97] Among the more famous recruits of this intelligence operation was W. Somerset Maugham, tasked to assassinate V. N. Chatterjee, who worked with the Berlin committee.[98]

Indian political intelligence

At this time, the foundation was laid for British counter-intelligence operations against the Indian revolutionary movement. In January 1910, John Arnold Wallinger, the Superintendent of Police at Bombay, was reassigned to the India Office in London, where he established the Indian Political Intelligence Office. Wallinger used his considerable skills to establish contacts with police officials in London, Paris and throughout continental Europe, creating a network of informants and spies.[99] During World War I, this organisation, working with the French Political Police, called the Sûreté,[100] was key in tracing the Indo-German conspiracy and attempted to assassinate ex-members of India House who were at the time planning a nationalist mutiny in British India.[98] Somerset Maugham, who was among Wallinger's recruits, later based some of his characters and stories on his experiences during the war.[101] Wallinger's organisation was renamed Indian Political Intelligence in 1921, and later expanded to form the Intelligence Bureau in independent India.[102]

Indian Communism

From the time it was founded, India House cultivated a close relationship with socialist movements in Europe. Prominent Socialists of the time like Henry Hyndman were closely linked to the house. Cama cultivated a close relationship with French Socilaists and Russian communists. The IHRS delegation to Stuttgart in 1907 is known to have met with Hyndman, Karl Liebknecht, Jean Jaurès, Rosa Luxemburg and Ramsay MacDonald. Chatterjee moved to Paris in 1909 and joined the French Socialist Party.[103] M.P.T. Acharya was introduced to the socialist circle in Paris in 1910.[104] With the help of the socialists in Paris, notably Jean Longuet, the Paris Indian Society brought pressure on the French Government when Savarkar was rearrested at Marseille after escaping from a ship that was deporting him to India.[105] Acharya utillused press freedom in France and the socialist platform to press for Savarkar's re-extradition to France and built French public opinion in support of such moves. Under public pressure at home, the French Government conceded and made a request to Britain, which was ultimately settled in Britain's favour at the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague.[105] The Paris Indian Society became one of the most powerful Indian organisations outside India at the time,[69] and grew to initiate contacts with not only French Socialists, but also those in continental Europe.[69] It sent delegates to the International Socialist Congress in August 1910, where Krishna Varma and Iyer succeeded in having a resolution passed demanding Savarkar's release and his extradition to France.[105]

[size=110;After World War I, ex-members of India House and erstwhile members of the Berlin Committee and the Indian revolutionary movement increasingly turned to the young Soviet Union, becoming closely associated with communism. The Berlin India Committee moved to Stockholm after the war. Led by V. N. Chatterjee, the committee wrote to Leon Trotsky to secure Bolshevik aid for the accused at the Hindu–German Conspiracy Trial.[106] Many involved in the conspiracy subsequently moved to Soviet Russia. When the Communist Party of India was founded in Tashkent in October 1920, a number of its founding members, including M. P. T. Acharya, Virendranath Chatterjee, Champakaraman Pillai and Abdul Rab, had been associated with India House or the Paris Indian Society.[107][108][109] Individuals like Acharya attended the second congress of the Communist International. Chatterjee and Acharya later worked with the League against Imperialism. Moving to Weimar Germany after the war, Chatterjee's program of revolutionary nationalism developed into the Indian Independence Party in 1922 which won Chicherin's approval and Comintern funding.[110] Chatto later joined the German Communist party. In 1927, Chatto accompanied Jawaharlal Nehru to the Brussels Conference of the League against Imperialism. However support from Soviet Russia for Chatterjee's program waned as M. N. Roy, a Bengali revolutionary in Moscow previously of the Anushilan Samiti was considered more close to ideology of Marxism than Chatterjee's aims of nationalist revolution. Roy steadily developed the Indian Communist Party with Stalin's encouragement and support. Chatterjee and Pillai later moved to Soviet Russia where they are believed to have been shot in Stalin's purges.Hindu nationalismA branch of the nationalist and revolutionary philosophy that arose from India House, especially from the works of V.D. Savarkar, was consolidated in India in the 1920s as an explicit ideology of Hindu nationalism. Exemplified by the Hindu Mahasabha, it was distinct from Gandhian devotionalism,[52] and acquired the support of a mass movement that has been described by some as chauvinist.[52] The Indian War of Independence is considered one of Savarkar's most influential works in developing and framing ideas of masculine Hinduism.[111] Amongst Savarkar's work during his stay at India House was a history of the Maratha Confederacy which he described as an exemplary Hindu empire (Hindu Padpadshahi).[52] Further, the Spencerian theories of evolutionism and functionalism that Savarkar examined at India House strongly influenced his social and political philosophy, and helped lay the foundations of early Hindu nationalism.[54] It charted the latter's approach to state, society and colonialism, and Spencer's doctrines led Savarkar to stress a "rationalist" and "scientific" approach to national evolution, as well as military aggression for national survival. A number of his ideas featured prominently in Savarkar's works well into his political writings and works with the Hindu Mahasabha.[54][112]

Commemoration Kranti Tirth, Shyamji Krishna Varma Memorial, Mandvi, Kutch. Replica of India House is visible in background.

Kranti Tirth, Shyamji Krishna Varma Memorial, Mandvi, Kutch. Replica of India House is visible in background.Krishna Varma's ashes along with those of his wife Bhanuben were repatriated to India in 2003 from Switzerland. Kachchh University, established by Gujarat government, is named in his honour. In 2010, a memorial named Kranti Teerth (Lit: Warrior's rest) was unveiled in his home town of Mandavi in Gujarat by (then) chief minister of Gujarat Narendra Modi.[113] Spread over 52 acres, the memorial complex houses a replica of India House building at Highgate along with statues of Krishna Varma and his wife. Urns containing Krishna Verma's ashes, those of his wife, and a gallery dedicated to earlier activists of Indian independence movement is housed within the memorial. Krishna Verma was disbarred from the Inner Temple in 1909. This decision was revisited in 2015, and a unanimous decision taken to posthumously re-instate him.[31] Savarkar's stay at India House is today commemorted with a blue plaque by English Heritage. Members of India House have been commemorated at various times independent India. Bhikaji Cama, Krishna Varma, Savarkar, among others have had commemorative postage stamps released by India Post. V. N. Chatterjee is commemorated at the Nehru Memorial Museum in New Delhi, where his name and photo is exhibited in a room for Indian revolutionaries. Dimitrov Museum in Leipzig housed a section on Chatterjee before it closed in 1989.[114]

Notes1. Fischer-Tinē 2007, p. 334

2. Mitra 2006, p. 63

3. Croitt & Mjøset 2001, p. 158

4. Desai 2005, p. xxxiii

5. Desai 2005, p. 30

6. Yadav 1992, p. 6

7. Bose & Jalal 1998, p. 117

8. Owen 2007, p. 63

9. Owen 2007, p. 37

10. Yadav 1992, p. 7

11. Owen 2007, p. 62

12. Pasricha 2008, p. 32

13. Abel 2005, p. 110

14. "India House". Open University. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

15. Hopkirk 1997, p. 44

16. Qur 2005, p. 123

17. b Johnson 1994, p. 119

18. Majumdar 1971, p. 299

19. Innes 2002, p. 171

20. Joseph 2003, p. 59

21. Joseph 2003, p. 58

22. Bose 2002, p. 4

23. Owen 2007, p. 67

24. Fischer-Tinē 2007, p. 330

25. Parekh 1999, p. 158

26. Sareen 1979, p. 38

27. Baruwa 2004, p. 24

28. Mahmud 1994, p. 67

29. Bose 2002, p. xix

30. Adhikari et al. 1970, p. 136

31. Bowcott, Owen. "Indian lawyer disbarred from Inner Temple a century ago is reinstated". The Guardian. Retrieved 2015-11-12.

32. Mahmud 1994, p. 47

33. Parekh 1999, p. 159

34. Israel 2002, p. 246

35. Owen 2007, p. 64

36. Owen 2007, p. 66

37. Owen 2007, p. 65

38. Yadav 1992, p. 8

39. Chirol 1910, p. 148

40. Lee 2004, p. 379

41. Bhatt 2001, p. 80

42. Joseph 2003, p. 61

43. Jaffrelot 1996, p. 26

44. Puniyani 2005, p. 212

45. Yadav 1992, p. 12

46. Parel 2000, p. 123

47. Wolpert 1962, p. 169

48. Ghodke 1990, p. 123

49. Yadav 1992, p. 4

50. Yadav 1992, p. 82

51. Yadav 1992, p. 9

52. Bhatt 2001, p. 83

53. Owen 2007, p. 70

54. Bhatt 2001, p. 81

55. Hopkirk 2001, p. 45

56. Popplewell 1995, p. 133

57. Hopkirk 2001, p. 46

58. Yadav 1992, p. 300

59. Heehs 1993, p. 90,91

60. Popplewell 1995, p. 98

61. Owen 2007, p. 72

62. Owen 2007, p. 71

63. Yadav 1992, p. 15

64. Popplewell 1995, p. 131

65. Fryer 1984, p. 269

66. Hopkirk 2001, p. 49

67. McMinn 1992, p. 299

68. Yadav 1992, p. 22

69. Yadav 1992, p. 26

70. Popplewell 1995, p. 127

71. Popplewell 1995, p. 128

72. Popplewell 1995, p. 129

73. Popplewell 1995, p. 130

74. Popplewell 1995, p. 130

75. Andreas & Nadelmann 2006, p. 74

76. Hopkirk 2001, p. 50

77. Popplewell 1995, p. 132

78. Owen 2007, p. 73

79. Popplewell 1995, pp. 138–140,142

80. Lahiri 2000, p. 125

81. Chambers 2015, p. in; References, chapter 2

82. Lahiri 2000, pp. 124–126

83. Lahiri 2000, pp. 124–128

84. Lahiri 2000, p. 126

85. Majumdar 1966, p. 121,147

86. Popplewell 1995, p. 135

87. Lahiri 2000, p. 129

88. "Dhingra, Madan Lal. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Oxford University Press. Retrieved 29 October2015.

89. Tickell 2013, p. 137

90. Fischer-Tinē 2007, p. 333

91. Fischer-Tinē 2007, p. 335

92. Fischer-Tinē 2007, p. 337

93. Fischer-Tinē 2007, p. 338

94. Hoover 1985, p. 252

95. Brown 1948, p. 300

96. Strachan 2001, p. 788

97. Hopkirk 2001, p. 41

98. Popplewell 1995, p. 234

99. Andreas & Nadelmann 2006, p. 75

100. Popplewell 1995, p. 216,217

101. Popplewell 1995, p. 230

102. Dover, Goodman & Hilleband 2013, p. 183

103. Sinha 2014, p. 48

104. Yadav 1992, p. 24

105. Yadav 1992, p. 25

106. Price 2005, p. 68

107. Radhan 2002, p. 120

108. Yadav 1992, p. 53

109. Strachan 2001, p. 815

110. Price 2005, p. 109

111. Bannerjee 2005, p. 50

112. Bhatt 2001, p. 82

113. TNN. "Modi dedicates 'Kranti Teerth' memorial to Shyamji Krishna Verma". The Times of India. Retrieved 2015-11-12.

114. Kara 1986, p. 17

References• Adhikari, G; Rao, MB; Sen, Mohit (1970), Lenin and India, Jhansi, India: People's Publishing House.

• Abel, M (2005), Glimpses of Indian National Movement, Hyderabad, India: ICFAI University press, ISBN 81-7881-420-X.

• Andreas, Peter; Nadelmann, Avram (2006), Policing the Globe: Criminalization and Crime Control in International Relations, Oxford: Oxford University Press US, ISBN 0-19-508948-0.

• Bannerjee, Sikata (2005), Make Me a Man! Masculinity, Hinduism, and Nationalism in India, Albany, New York: SUNY press, ISBN 0-7914-6367-2.

• Baruwa, Niroda Kumara (2004), Chatto, the Life and Times of an Indian Anti-imperialist in Europe., Oxford University Press India, ISBN 978-0-19-566547-5.

• Bhatt, Chetan (2001), Hindu Nationalism: Origins, Ideologies and Modern Myths, Oxford: Berg Publishers, ISBN 1-85973-348-4.

• Bose, Arun (2002), Indian Revolutionaries Abroad, 1905–1927: Select Documents, Volume 1, New Delhi: ICHR, ISBN 81-7211-123-1.

• Chambers, Claire (2015), Britain Through Muslim Eyes: Literary Representations, 1780–1988, New Delhi: Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-230-25259-2.

• Bose, Sugata; Jalal, Ayesha (1998), Modern South Asia: History, Culture, Political Economy, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-16952-6.

• Brown, Giles (1948), "The Hindu Conspiracy, 1914–1917", The Pacific Historical Review, University of California Press, 17 (3): 299–310, doi:10.2307/3634258, ISSN 0030-8684.

• Chirol, Valentine (1910), Indian Unrest, London: MacMillan and Co., ISBN 0-543-94122-1.

• Croitt, Raymond D; Mjøset, Lars (2001), When Histories Collide, Oxford, UK: AltaMira, ISBN 0-7591-0158-2.

• Desai, A.R (2005), Social Background of Indian Nationalism, Mumbai: Popular Prakashan, ISBN 81-7154-667-6.

• Dover, Robert; Goodman, Michael; Hilleband, Claudia (2013), Routledge Companion to Intelligence Studies, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-50752-3.

• Fryer, Peter (1984), Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain, University of Alberta, ISBN 978-0-86104-749-9

• Ghodke, H.M. (1990), Revolutionary nationalism in western India:On the contribution of Maharashtra to the Indian freedom struggle., Classical Publishing Company, ISBN 81-7054-112-3

• Heehs, Peter (1993), The Bomb in Bengal: The Rise of Revolutionary Terrorism in India, 1900–1910, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-563350-4

• Hopkirk, Peter (1997), Like Hidden Fire: The Plot to Bring Down the British Empire, Kodansha Globe, ISBN 1-56836-127-0

• Fischer-Tinē, Harald (2007), "Indian Nationalism and the 'world forces': Transnational and diasporic dimensions of the Indian freedom movement on the eve of the First World War", Journal of Global History, Cambridge University Press, 2 (3): 325–344, doi:10.1017/S1740022807002318, ISSN 1740-0228.

• Hoover, Karl (1985), "The Hindu Conspiracy in California, 1913–1918", German Studies Review, German Studies Association, 8 (2): 245–261, doi:10.2307/1428642, ISSN 0149-7952, JSTOR 1428642.

• Hopkirk, Peter (2001), On Secret Service East of Constantinople, Oxford: Oxford Paperbacks, ISBN 0-19-280230-5.

• Innes, Catherine Lynnette (2002), A History of Black and Asian Writing in Britain, 1700–2000, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-64327-9.

• Israel, Milton (2002), Communications and Power: Propaganda and the Press in the Indian National Struggle, 1920–1947, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-46763-6.

• Jaffrelot, Christofer (1996), The Hindu Nationalist Movement and Indian Politics, London: C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, ISBN 1-85065-301-1.

• Johnson, K. Paul (1994), The Masters Revealed: Madame Blavatsky and the Myth of the Great White Lodge, Albany, New York: SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-2063-9.

• Joseph, George Verghese (2003), George Joseph, the Life and Times of a Kerala Christian Nationalist, Hyderabad, India: Orient Longman, ISBN 81-250-2495-6.

• Lahiri, Shompa (2000), Indians in Britain: Anglo-Indian Encounters, Race and Identity, 1880–1930, London: Frank Cass publishers, ISBN 0-7146-8049-4.

• Kara, Maniben (Ed) (1986), The Radical Humanist, Vol 50, Bombay: Indian Renaissance Institute.

• Lee, Sidney (2004), King Edward VII: A Biography Part II, Oxford, UK: Kessinger Publishing, ISBN 1-4179-3235-X.

• Mahmud, Syed Jafar (1994), Pillars of Modern India, New Delhi: Ashis Publishing House, ISBN 81-7024-586-9.

• Majumdar, Ramesh C (1971), History of the Freedom Movement in India (Vol I), Calcutta: Firma K. L. Mukhopadhyay, ISBN 81-7102-099-2.

• Majumdar, Bemanbehari (1966), Militant Nationalism in India and Its Socio-religious Background, 1897–1917, Calcutta: General Printers and Publishers

• McMinn, Joseph (1992), The Internationalism of Irish Literature and Drama, Savage, Maryland: Barnes & Noble, ISBN 0-389-20962-7.

• Mitra, Subrata K (2006), The Puzzle of India's Governance: Culture, Context and Comparative Theory, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-34861-7.

• Owen, Nicholas (2007), The British Left and India, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-923301-2.

• Parekh, Bhiku C. (1999), Colonialism, Tradition and Reform: An Analysis of Gandhi's Political Discourse, New Delhi: Sage Publications, ISBN 0-7619-9383-5.

• Pasricha, Ashu (2008), The Encyclopaedia Eminent Thinkers, New Delhi: Concept Publishing Co, ISBN 978-81-8069-491-2.

• Parel, Antony (2000), Gandhi, Freedom, and Self-rule, Oxford: Lexington Books, ISBN 0-7391-0137-4.

• Popplewell, Richard J (1995), Intelligence and Imperial Defence: British Intelligence and the Defence of the Indian Empire 1904–1924, London: Frank Cass, ISBN 0-7146-4580-X.

• Price, Ruth (2005), The Lives of Agnes Smedley, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-534386-1.

• Puniyani, Ram (2005), Religion, power & violence, New Delhi: Sage Publications, ISBN 0-7619-3338-7.

• Qur, Moniruddin (2005), History of Journalism, New Delhi: Anmol Publications, ISBN 81-261-2355-9.

• Radhan, O.P (2002), Encyclopaedia of Political Parties, New Delhi: Anmol, ISBN 81-7488-865-9.

• Sareen, Tilak Raj (1979), Indian Revolutionary Movement Abroad, 1905–1921., New Delhi: Sterling.

• Sinha, Babli (2014), South Asian Transnationalisms: Cultural Exchange in the Twentieth Century., Oxford: Routledge, ISBN 9780415556187.

• Strachan, Hew (2001), The First World War. Volume I: To Arms, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-926191-1.

• Tickell, Alex (2013), Terrorism, Insurgency and Indian-English Literature, 1830-1947, Routledge, ISBN 0-19-926191-1.

• von Pochhammer, Wilhelm (2005), India's Road to Nationhood. (2nd edition), Mumbai: Allied Publishers, ISBN 81-7764-715-6.

• Wolpert, Stanley (1962), Tilak and Gokhale: Revolution and Reform in the Making of Modern India, University of California Press.

• Yadav, B.D (1992), M.P.T. Acharya, Reminiscences of an Indian Revolutionary, New Delhi: Anmol Publications Pvt ltd, ISBN 81-7041-470-9.