Chapter 6: Writing Politics

Any émigré intellectual who wishes to remain alive must either lose his nationality or accept the revolution in one way or another.

-- D.S. Mirsky, 1931

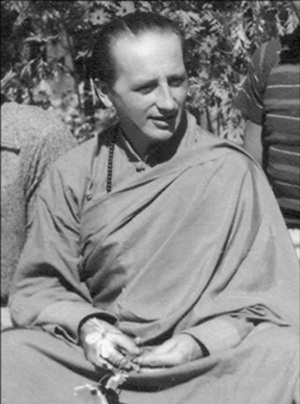

GOING TO GORKY

The final phase of Mirsky’s life in emigration began with an event that explicitly raised the idea of his going back to Russia: during the Christmas vacation of 1927-8 he went with Suvchinsky to visit Maksim Gorky in Sorrento. Many years later, Suvchinsky told Veronique Lossky: ‘One day Mirsky asked me to go with him, and we spent Christmas at Gorky’s … We were followed the whole time. Gorky tried to persuade us to go to Russia, saying “I’ll fix you up”, and he convinced Mirsky and me.’1 Suvchinsky told me: ‘I had known Gorky back in Petersburg-Petrograd and met him at Shalyapin’s. D.P. didn’t know him and asked me to introduce him. I exchanged letters with Gorky and we got visas through the poet Ungaretti, which at that time was not easy.’2

On what basis exactly Gorky promised Mirsky and Suvchinsky that he could ‘fix them up’ in Russia is a puzzle, because Gorky’s own standing at this tie was not at all clear. He had been given his marching orders by Lenin in October 1921 because of the persistent criticism he leveled at the new regime, chiefly in his journal Untimely Thoughts, on the basis of its record in human rights and freedom of information; he had not been back to Russia since.3 Gorky lived at first in Germany; in the spring of 1924 he moved to Sorrento. Mussolini would not allow him back onto Capri, where Gorky, as a political exile with a massive international reputation and correspondingly large income, had created a refuge for the Russian revolutionaries before 1914. In his rented villa in Sorrento he lived as before with a substantial entourage, which now included two additions of particular significance: the enigmatic Moura Budberg4 and also the more obvious eyes of the NKVD in the form of Gorky’s ‘secretary’, Pyotr Kryuchkov.

It is clear from Mirsky’s letters to Suvchinsky in the run-up to their visit that Mirsky not only made the necessary arrangements, but also paid Suvchinsky’s expenses. Giuseppe Ungaretti (1881-1970) was employed at the time in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Rome; he was the Italian literary adviser to Commerce, and Mirsky would have known him in that connection. Mirsky may not have been personally acquainted with Gorky, but the latter certainly knew who he was. Gorky had noted and commented on the publication of Vyorsts in one of his regular reports about what was going on in Western Europe, a letter of 24 July 1926 to A.K. Voronsky in Moscow:

The editor is Prince Svyatopolk-Mirsky, apparently the son of the one who promised to make a ‘spring’ in 1901-2. He’s a very clever and independent critic who writes superlative characterizations of Zaitsev, Merezhkovsky, Khodasevich and others. There are reprints of Artyom Vesyoly … Babel … Pasternak … But the Eurasians are in here too – Lev Shestov, Artur Lurie, and of course, Marina Tsvetaeva and Remizov. It’s a princely affair.5

In a letter written from Sorrento on 6 January 1928 to the novelist Olga Forsh, Gorky speaks of ‘the Eurasian Suvchinsky, who is living at the Minerva6 together with one of the descendants of Svyatopolk the Accursed’.7 Since Mirsky was anything but the kind of person who paid visits to celebrities just because they were celebrities, there must have been a weighty reason for his approaching Gorky. He had no illusions whatsoever about the ambiguities of Gorky’s personality and political stance; in his writings Mirsky had mercilessly formulated the ethical reservations about him that were standard among the émigré intelligentsia:

With an enormous insight into reality, Gorki has no love of truth. And as he has no motive to restrain him from telling half-truths, and insinuating untruths, his essays more often than not become grotesque distortions of reality. This practically nullifies his moral weight in the eyes of all Russians. And it seems Gorki will be richly repaid for his contempt of the Russian people. Even now he is not taken seriously except by foreigners, for the Bolsheviks use him only as a convenient signboard to be contemplated from beyond the pale.8

Side by side with remarks of this kind, though, Mirsky had constantly stressed Gorky’s pre-eminent status among living Russian writers, and spoken warmly of his efforts to maintain links between the divided worlds of Soviet and émigré culture. The obvious reason for going to see Gorky would have been in order to forge such a link, presumably with reference to the Eurasian movement, because at this stage Mirky did not want to go directly to an official Soviet representative. Meanwhile, several significant but inconclusive pointers suggest that in 1927 the Eurasian leadership did attempt a direct rapprochement with the Soviet authorities, as we will see.

To get Gorky back to Russia was an important objective of Soviet policy. Khodasevich observed in 1925: ‘The most compromising thing about the Bolshevik paradise is that those who adore it would do anything rather than live there.’9 He was referring specifically to Erenburg, but Gorky was the prime illustration of this notion in the public mind. After Gorky settled in at Sorrento, a stream of Soviet writers started to visit, always with the permission of their own and the Italian authorities, neither of which was easy to secure. His visitors eventually included several representatives of the new literary elite, both Party members and fellow-travelers: the poets Aseev and Marshak, the novelists Babel (whose Italian visa was facilitated by Mirsky), Olga Forsh, Vsevolod Ivanov, and Valentin Kataev, and the playwright Nikolay Erdman. In the autumn of 1927 Sholokhov was on his way, but he was refused an entry visa by the Italians. Just before Mirsky and Suvchinsky went to see Gorky, Anastasiya Tsvetaeva had paid him a visit, and towards the end of it she went to see her sister Marina in Paris; there may well have been some direct connection between this visit and that of the two Eurasians.10

Also in the autumn of 1927, Gorky was visited by Kamenev, who had just been appointed Soviet Ambassador to Italy;11 this seems to have been the moment when an agreement was struck that Gorky would come back to Russia. How and when he would come, though, was a ticklish business. For one thing, the state of Gorky’s health was more than a politically convenient excuse for his spending at least the winters outside Russia. But the main problem was, of course, the delicate relationship between Gorky and Stalin. Gorky had immaculate credentials as a close personal friend of Lenin, and such people were increasingly felt to be a threat by his successor.

Mirsky expressed the public face of his private feelings about his visit in a letter he wrote to Gorky from London on 2 February 1928:

I have been meaning to write to you ever since I left, and I still can’t find the right words to tell you what an enormous blessing our meeting was for me. I probably never will be able to, but I feel that I was not in Sorrento but in Russia, and that this time I spent in Russia really straightened me out. There is no other man who could bear Russia within himself like you do, and not only Russia, but also that quality without which Russia cannot exist – humanity…. As we were leaving, Suvchinsky said to me ‘We never saw Tolstoy, though!’ Tolstoy was the only person we could think of. But you are more Russian, you ‘represent’ Russia, more than Tolstoy did.12

Writing a week later, on 9 February 1928, Mirsky put to Suvchinsky a leading question, and answered it himself: ‘I keep asking myself what divides us (me) from the Communists? Only first principles.’ Mirsky attributed particularly great important to the visit to Gorky in the account of his intellectual development that he wrote after he had joined the Communist Party in 1931:

Leaving aside the unforgettable impression made on me by the great charmer that was Gorky, this visit was our first direct contact with ‘the other side of the barricade’ and our first breath of pure materialist air from regions uninfected by the metaphysical miasma we had been breathing.13

At this time, though, the thoughts of going back to Russia that Mirsky says were stimulated by the visit to Gorky were left to lie fallow; nearly three years went by before Mirsky next contacted him. As we shall see, Mirsky was not at first thinking in terms of going back for good. In fact, until about a year before he actually left for Moscow, he seems to have conceived the enterprise as a visit and no more. Gorky’s example, or perhaps even Gorky’s own advice, may have suggested that it would be possible to go and come back.

AMERICA

Instead of turning irrevocably east, Mirsky did the opposite. He finally paid his long-mooted visit to the USA in the summer of 1928, as a result of an invitation from Columbia University that had been brokererd by Michael Florinsky. After this visit, Mirsky considered taking up a permanent academic appointment in America. The idea of America had been part of his consciousness since his earliest days in emigration: through the intermediacy of Bernard Pares, whose connections with American Russianists were of long standing, Mirsky’s books had found parallel American publishers, and he had contemplated a lecture tour as early as 1924. After Florinsky moved to New York in 1926, one of his first letters sounds Mirsky out about a possible job at Columbia University. Later, Florinsky offered to fix up a lecture tour so that Mirsky could have a look round. On 6 December 1926 Mirsky replied that he would be glad to come, but ‘for this I’d like to receive a goodly amount of dollars, since three weeks on the ocean is worth that’. He also said that he could only be released in the summer term. On 14 February 1927 Mirsky told Florinsky that he had had an invitation from Clarence Manning14 to give a lecture series from 1 to 15 July 1928 for 600 dollars. Very soon after this, though, Mirsky made an abrupt about-turn, telling Florinsky: ‘I must say honestly, though, that I absolutely don’t want to come to America, and I’ll take it on only out of a sense of duty. To hell with it [Nu ee sovsem]. I attach three copies of my biography.’

Eventually Mirsky sailed for America on 27 June 1928. Two letters survive that he wrote to Suvchinsky from New York. In the first, he hints that something to do with the Eurasian connection had gone seriously wrong there. Malevsky-Malevich had been active on behalf of the Eurasians, and Mirsky took a dim view of the results:

Unfortunately, I’m not seeing much of the Americans. The Russians are mediocrities, on the whole worse than those in Paris, with a few exceptions. I haven’t seen any Eurasians and I think it’s not worth it, I can see from here they’re mediocrities. Malevsky has debauched himself here to the limit. Perhaps I’ll still try and say a few warm words to them.15

In the second letter from New York, written on 9 August, Mirsky claims to have established a link with the Department of State and to be trying to fix up a meeting with the head of the Russian section for Suvchinsky or Arapov when that person is next in Paris. Whether anything came of this is unknown, but it seems unlikely that anything did. Mirsky gave three lectures at Columbia, Cornell, and Chicago. The lecture at the University of Chicago was delivered on 31 July in the Harper Assembly Room, and its subject comes as rather a surprise in the light of the way Mirsky’s views were developing at this time: ‘Elements of Russian Civilization: Russia and the Orthodox Church’.16

EURASIANISM EXPANDS

Meanwhile, at the same time as he was planning his trip to America and writing his major historical works in English, the main concern of Mirsky’s practical life increasingly became Russian politics, and in particular the politics of the Eurasian movement. The letters to Suvchinsky show that from about the middle of 1926 Mirsky was constantly offering advice about the policy decisions that were being taken by the Eurasian leadership.

Mirsky was not the only, not yet the most influential, newcomer to the leadership of the movement at this time. Lev Karsavin became involved with Eurasianism soon after he arrived in Berlin in 1923.17 Karsavin’s candidacy for a leading position in the movement was initially treated with considerable reservation by Trubetskoy and Savitsky, but Suvchinsky apparently convinced them to take him on purely as an expert adviser. In talking about Karsavin in this connection, Suvchinsky uses the current Soviet slang term for an expert, spets, which Savitsky thought deeply suspicious when the branch of expertise concerned was religion. Mirsky’s reaction to Karsavin was similar, and ominous; he wrote to Suvchinsky on 8 August 1926:

Forgive me, but I can’t help sensing in [Karsavin] something that is in the highest degree spiritually unsound … -- his entire approach is the purest utilitarianism, isn’t it? He’s a nihilist and a blasphemer, and his very theologizing looks to me like a sort of refined defamation.

The generation that was born in the years of Dostoevsky’s evil deeds (Notes from Underground, 1864-1881!) will not bring forth sound fruit. And if you take him on purely as a spets in theology, isn’t that doing things the Latin way? Does Orthodoxy really have any familiarity with this kind of spetsish theologianizing that has no connection with the spiritual essence?

Karsavin moved to Paris in July 1926 and settled in Clamart, where Suvchinsky and also Berdyaev (and later Tsvetaeva) lived. That autumn Karsavin instituted a Eurasian seminar there; it became the ideological engine of the movement. This was the first articulation of the schism between Paris and Prague that was to wreck Eurasianism in 1929.

Three other men became prominent in the Eurasian movement at the same time. Vladimir Nikolaevich Ilin (1890-1974) was another philosopher who had been expelled from Russia in 1922; he had contributed an essay to the Eurasian volume of 1923 on East-West ecclesiastical relations. He was resident in Prague. The legal scholar Nikolay Nikolaevich Alekseev (1879-1964) was also resident in Prague; from 1926 he began publishing essays that attempt to construct a Eurasian theory of the state and law. Finally, Vasily Petrovich Nikitin (1885-1960) began contributing essays to Eurasian publications on the relations between Russia-Eurasia and the Middle East.

The contemporary published documents give no precise indication about how the Eurasian movement was formally managed. Though the Eurasian Chronicle contains a good deal of information about various events, there are no systematic reports of when and where meetings were held or how many people attended them, not to mention any financial accounts. It may well be that there was in fact no formally constituted structure, no protocols and formalized proceedings. Some evidence about the high command of the Eurasian movement after 1925, though, has emerged from the previously secret materials that have become available since the downfall of the USSR.

The earliest such documents are two ‘Protocols’ of March 1923 in which ‘the three Ps’, as they call themselves – Arapov, Suvchinsky, and Savitsky (who shared the first name Pyotr) – discuss Eurasian publishing policy, and another ‘Protocol’ of June 1923 in which the same three set out a concise definition of the nature and aims of the movement. Their concluding paragraph is of considerable interest:

In practical matters, the first and foremost essential is circumspection. Effort should be concentrated in the first instance on spreading the spiritual influence of Eurasian ideas in Russia, and in the second, on the creation of a circle of persons spiritually connected with each other and variously gifted in terms of action.18

In 1927 Karsavin left Paris to take up a teaching post at the University of Kaunas in Lithuania, but he remained an active Eurasian until the schism of 1929.19 He lived in Kaunas until 1940, when his university removed to Vilnius. He lost his job after the Soviet occupation in 1945, and was duly arrested on 9 July 1949. He was then interrogated, mainly about the Eurasian movement.20 He stated that in 1926, when he first became involved, there was a Council (Soviet), which consisted of five men. In the order in which Karsavin names them, and which seems to indicate a hierarchy at least in his mind, they were: Trubetskoy, Savitsky, Suvchinsky, Arapov, and Malevsky-Malevich. At a congress in Prague in 1926, this Council chose a four-man Politbyuro – the Soviet-style term is indicative – which consisted of Trubetskoy, Suvchinsky, Malevsky-Malevich, and Arapov. The Council was then expanded; Karsavin himself joined it, but according to his own testimony he soon resigned. Three others joined the Council in or around 1926, precisely at what date Karsavin does not say; they were ‘the former Russian consul in Persia, Nikitin; colonel of the Tsar’s army Svyatopolk-Mirsky; and the officer Artomonov’. If this statement is accurate, it means that in the run-up to the schism the governing body of the Eurasian movement consisted of eight men, of whom Mirsky was one.

Karsavin himself seems to have been involved only in the public activities of the Eurasians. There was, though, another side to the movement, which Karsavin does not discuss, but which may be inferred from a passage in Mirsky’s essay of 1927:

In practical politics the Eurasians condemn all counter-revolutionary activity, not to speak of political terror or foreign intervention. They do not, however, abdicate from making propaganda for their ideas in the U.S.S.R., and signs are not lacking that these ideas are being favourably accepted inside the Union by ever-increasing numbers.21

Behind this coy reference to propaganda for their ideas in the USSR there lay in fact an extensive covert operation.

All the published accounts of Eurasianism suggest that it began as a purely intellectual enterprise, but was then hijacked and betrayed in about 1925-6 by politically motivated scoundrels, with Mirsky prominent among them. The story is usually told as a decline and fall from the innocence of the preternatural spiritual quest of the Russian intelligentsia to a Boshevik-bedevilled mess of cynical politicking.

This interpretation is not seriously defensible. Apart from anything else, the financial support that enabled the Eurasian movement, the ‘Spalding money’, came from a source whose motivation may not have been purely philanthropic, to say the least, and it was secured not by the Continental intellectuals but, according to most accounts, by Malevsky-Malevich, and negotiated with the aid of Arapov. Malevsky-Malevich and Arapov were quite different from Trubetskoy and Savitsky. They came not from intelligentsia, but from the executive arm of the old Imperial ruling class. Like Mirsky, they had both been career army officers in crack regiments, and they had served in the high command of the White armies during the Civil War. Exactly how much Mirsky knew about their activity when he wrote the passage about not abdicating from making propaganda in the USSR is unclear, but there is considerable circumstantial evidence to suggest that in fact he knew a great deal.

The role of Savitsky in all this is enigmatic. He was by no means a closeted intellectual of the kind that Trubetskoy made himself out to be.22 There is abundant evidence to suggest that Savitsky really did believe that the Eurasians could take power in Russia, that he fancied his own chances of assuming a leading position, and that he was deeply involved in political manoeuvring and covert activities. He made at least one covert trip to Russia, in the latter half of January and early February 1927, and boasted about the warmth of his reception, especially the fact that he was able to take Communion at a Moscow church.

The most detailed account published so far of the covert activities of the Eurasians comes from another source that only became available after the collapse of the USSR. On the night of 9/10 October 1939, just over a year after he was repatriated to Russia, Sergey Efron was arrested, and subjected to lengthy interrogation.23 The main focus was his participation in the Eurasian movement. His captors’ task was to build the case that the Eurasians had been a prime focus of anti-Soviet activity in the emigration, and to incriminate everyone who had been involved in it.24 Efron appears to have conducted himself with immense fortitude under interrogation. There is no reason to suppose that he told anything but the truth when his mental balance was judged to be disturbed; he was confined for a while in the psychiatric section of the Butyrka Prison after attempting suicide, and he was repeatedly beaten. The contents of these interrogations are grotesque to a degree that makes Darkness at Noon seem infantile. Efron repeatedly ‘confesses’ that he did indeed make contact with various Western intelligence services, but his equally genuine insistence that he did so under instructions from his GPU controller is unacceptable to the NKVD interrogator of 1939, because this aspect of the truth does not fit his brief, which was to prove that Efron was working against the USSR as a hired agent of foreign powers and not on behalf of it as a willing collaborator.

Efron stated that the Eurasians had two principal political goals for the future of Russia: first, the replacement of the economic monopoly of the state by state capitalism; and secondly, the replacement of Communists in the Soviet administrative structure by Eurasian sympathizers. To work for these goals there was a covert wing within the movement in emigration. Its activity was divided into three sectors. The first sector, said Efron, was concerned with the dispatch of Eurasian literature into the USSR, using in part the Polish diplomatic bag. This sector was organized by Konstantin Rodzevich and Pyotr Arapov. The second sector was concerned with sending emissaries into the USSR. This was undertaken through a body that Efron refers to as ‘the Trust’. Efront does not immediately say who ran this sector, but from his subsequent answers it is clear that the principal figure involved was also Pyotr Arapov. The task of the third sector, much less covert, was to spread Eurasian propaganda among Russians in France. This activity was organized by Efron himself; he would arrange meetings and discussion sessions, to which Soviet citizens living abroad as well as émigrés would be invited.

With the hindsight of seventy years, these goals and methods may seem intrinsically unrealistic, but in fact they represent one particular facet of the extensive practical efforts to undermine the Soviet regime that began in the emigration when the regime itself began, and ceased only with the collapse of the USSR in 1991. From the perspective of the post-Soviet period, one fundamental similarity between the Eurasian programme and that of Stalin’s CPSU is more striking than anything else: the Eurasians had no respect for what Mirsky once called ‘the paraphernalia of liberal democracy’, by which he meant government by popularly elected representatives. Mirsky explained Eurasian thinking on this point as follows:

They have given the name of ‘ideocracy’ to the system of government they propose. They visualize it as exercised by a unique party united by one idea, but an idea accepted by the symphonic personality of the People. Here again Communism and Fascism have to be regarded as rough approximations to a perfect ideocratic state. The insufficiency of Fascism lies in the essential jejuneness of its ruling idea, which has little content apart from the mere will to organize. The insufficiency of Communism lies in the only too obvious contradiction between a policy that is ideocratic in practice, and the materialist philosophy it is based on, which denies the reality of ideas, and reduces all history to processes of necessity.25

In Mirsky’s mind, this contradiction was soon to be resolved, as it was for so many others, by an acceptance of Stalin as the embodiment of ‘willed necessity’ (to cite a standard Soviet definition of freedom); Mirsky thus found a focus for the voluntarist principle that was central to all his positive judgments. But the fundamentally anti-democratic position of Eurasianism made it vitally cognate with the Soviet system, so that the politically minded Eurasians could reasonably think in terms of taking over that system and re-ideologizing it rather than conducting another revolution that involved the masses.

The most intriguing aspect of Efron’s deposition of 1939 concerns what he refers to as ‘the Trust’. This has long been known to have been the cover-name used for the most successful operation mounted by the Soviet secret service in the 1920s. Its activities have been described several times in English and elsewhere, but the Eurasians make hardly any appearance in these accounts.26 The Trust was a fictional anti-Soviet organization on Soviet territory invented by the GPU to smoke out, draw in, and eventually control anti-Soviet activity based abroad. The only authoritative account of this organization by someone who was actually involved with it outside Russia was written by S.L. Voitsekhovsky, a former White officer who was in emigration from September 1921 and seems to have become involved in covert activity very soon after that.27 Voitsekhovsky never makes clear the precise relationship between the émigré monarchist organizations on the one hand and the Eurasians on the other. This would appear to be because for him, as for many others, the relationship never actually was clear at the time. They evidently used the same channels of communication and shared some personnel, principally Pyotr Arapov. Several Russian scholars have stated with great confidence on the basis of archival documents that the Trust in fact penetrated the Eurasian movement via Pyotr Arapov as early as December 1922.28 Arapov did not simply write letters and send money into Russia; he was also a courier.

Pyotr Semyonovich Arapov remains one of the most enigmatic figures in Mirsky’s life. Apparently a few years younger than Mirsky, he was a nephew of General Vrangel, commanded his personal escort during the Civil War, and earned a reputation for ruthless cruelty.

Chapters Four through Seven examine Aufbau's rise and fall in Munich from 1920 to 1923. Aufbau gained its initial impetus from the cooperation between former volkisch German and White emigre Kapp Putsch conspirators located in Bavaria and General Piotr Vrangel's Southern Russian Armed Forces, which were based on the Crimean Peninsula in the Ukraine. Scheubner-Richter led a dangerous mission to the Crimea to specify the terms of mutual support between his right-wing German and White emigre backers in Bavaria and Vrangel's regime. The Red Army soon overran the Crimean Peninsula and sent Vrangel and his soldiers fleeing, but Scheubner-Richter nonetheless turned Aufbau into the dynamic focal point of volkisch German-White emigre collaboration.

-- The Russian Roots of Nazism: White Emigres and the Making of National Socialism, 1917-1945, by Michael Kellogg

In emigration, he seems to have been prominent in both the militant monarchist and the Eurasian movements. Under interrogation, Sergey Efron said that Arapov told him that he was connected with the intelligence services of Poland, Germany, and perhaps England; and that he had made these connections at the behest of the GPU. It seems abundantly clear that Arapov had been a Soviet agent from the start, but his motives and procedures for becoming one have gone with him to his unmarked grave. Suvchinsky and Savitsky knew about his connections with the Trust and his trips to Russia, but they seem to have taken all this at face value.

The nature of Mirsky’s relationship with Arapov, and some details of Arapov’s activities, can be reconstructed from the many passing references to him in Mirsky’s letters to Suvchinsky. Arapov lived with the Golitsyn family, Mirsky’s old friends, at Chessington in Surrey. He appears to have had no regular employment, but nonetheless to have been able to travel frequently between England and the Continent without difficulty. Mirsky first came into contact with Arapov late in 1922. The evidence in Mirsky’s letters to Suvchinsky about Arapov indicates that Mirsky regarded him as a ruthless, even unscrupulous man of action whose limited intellectual capabilities were an invaluable corrective to the endless theorizing of Savitsky and Suvchinsky. A firm friendship developed between the two men during the 1920s. Mirsky says several times that he misses Arapov badly when the latter is away on his various missions; it can be inferred from Mirsky’s letters to Suvchinsky that Arapov went to Russia in February 1925, February 1928, and December 1929. There may well have been other trips; the first of them may have taken place in September 1924.29

In strong contrast to his attitude towards Aropov, it is clear from the letters to Suvchinsky that Mirsky soon came to detest the other leading Eurasian who was based in England, Pyotr Nikolaevich Malevsky-Malevich (1891-1974). The latter published a New Party in Russia (London, 1928), which Mirsky derided almost as sarcastically as he did Spalding’s effort of the same year.30 The fact that these two books, the only contemporary accounts of the Eurasian movement in a language other than Russian, were published in English in London, suggests that they might have been undertaken as an effort to convince some paymaster of the value that was being obtained for his money. Where Malevsky-Malevich’s funding came from is obscure; like Arapov, he seems to have been a frequent international traveler on Eurasian and other business – he was certainly the principal Eurasian connection with the USA – but not to have held any kind of salaried post. Whatever may be the case, Malevsky-Malevich remains the most mysterious figure in the Eurasian high command.

THE NEWSPAPER EURASIA

Mirsky was back in London from America on 28 August 1928. In the first fort-night of October he sent off to Suvchinsky in Paris his first contributions to the newspaper that had been proposed in Eurasian circles.31 Mirsky then wrote an enigmatic letter to Suvchinsky on 16 October in which he outlines a project he calls ‘hommage a l’URSS’. He tells Suvchinsky that John Squire had promised an article on Lenin, and that on Leonard Woolf’s advice he had written to Maurice Dobb, Kingsley Martin,32 and Lowes Dickinson.33 Mirsky asks Suvchinsky what he should tell ‘these gents’ about fees. It looks as if this was a plan to get some prominent British left-wingers to write something about Soviet Russia.

Mirsky wrote to Salomeya Halpern from London on 6 November 1928 that he had been impossibly busy with Eurasian business during his recent time in Paris and unable to find the time to see even her. He did find the time to meet Mayakovsky on this occasion, though, and described him in this letter offhandedly – showing his own customary lack of seriousness towards Halpern – as ‘a very serious man’. For the public record he later said something much more substantial:

A future biographer will be faced with establishing to what extent this soul, ‘squeezed out’ of his work, found its revenge by manifesting itself in life. People who knew Mayakovsky well will perhaps write about this. On people who knew him superficially (like myself) he made, in the last years of his life, an impression of the greatest self-restraint and of feeling a sense of responsibility for every word he said.34

This meeting with Mayakovsky undoubtedly fuelled Mirsky’s push to have Tsvetaeva’s notorious salutation to him published in Eurasia.

The salutation itself has a headline in small type that runs over two columns: ‘V.V. Mayakovsky in Paris’, and beneath it: ‘V.V. Mayakovsky is presently a guest in Paris. The poet has given more than one public reading of his work. The editorial board of Eurasia offer below Marina Tsvetaeva’s salutation to him.’ Tsvetaeva’s words are set in two vertically parallel columns:

On 22 April 1922, the eve of my departure from Russia, early in the morning, on the completely deserted Kuznetsky I met Mayakovsky. ‘Well then, Mayakovsky, what message d’you want me to pass on to Europe?’

That the truth is over here.’

On 7 November 1928, late in the evening, as I was coming out of the Café Voltaire somebody asked me:

‘What d’you say about Russia after hearing Mayakovsky?’ – and I replied without hesitation: ‘That the power is over there.’

This item was not carried demonstratively on the front page of the first issue of Eurasia, as has sometimes been asserted, but as a tiny item squeezed into the top right-hand corner of the back page. This is telling evidence about how few people have actually ever seen the original; a complete run of the newspaper is perhaps the rarest of all Eurasian printed documents.

The first issue begins with an anonymous editorial that takes up half the front page and does not mention Eurasianism by name at all; instead, it speculates about various attitudes towards the Russian revolution and the building of the New Russia. An article by Trubetskoy, ‘Ideocracy and the Proleteriat’, begins at the top of the extreme right-hand column of the first page and continues on the top right-hand third of the second page. Its tone is strongly pro-Soviet, endorsing the dictatorship of the Party. The article continues in the second issue on 1 December. This was to be the only article Trubetskoy contributed to the newspaper. The dominant think-pieces that carry a signature in the first and other early issues are by Karsavin; his ‘The Meaning of Revolution’ occupies what Russians call the ‘cellar’ at the bottom of the first and second pages, and spills over onto the third. The middle sections of thepaper bring on some much more obscure figures. ‘An Assessment of the Economic Situation of the USSR’ by A.S. Adler, and ‘Points of Departure of Our Politics’ by N.N. Alekseev both manage to end on a hyphenated word on page 3 and continue on page 4, but at least they both end there without further spillage. The first issue also contains three anonymous items containing summary information, one concerning economic developments in the USSR, the second concerning major international events, and the third concerning events in the Russian emigration. Nikitin occupies the cellars on pages 5 and 6 with ‘The East and Us’. Then, relegated to the back as usual, come cultural affairs. There is a turgid survey article of current French literature over the odd signature ‘Ajaxes’, which the letters of Mirsky to Suvchinsky reveal to have been a pseudonym used by Malevsky-Malevich. And finally, at the back, comes Mirsky.

At some stage during the early work on the paper, Suvchinsky drafted an article under the title ‘The Revolution and Power’, which is a kind of pro-Soviet manifesto and eventually appeared in No. 8 on 12 January 1929. The manuscript text was shown to Trubetskoy, who wrote a letter strongly objecting to it. On 1 December 1928 Mirsky wrote to Suvchinsky that he had just seen Malevsky-Malevich, who had shown him Trubetskoy’s letter about this article. Mirsky responded:

This is of course a very serious crisis, and in my opinion we should try and deepen it, i.e. go for a final break. It’s clear that this is what Trubetskoy wants, and I don’t blame him all that much, knowing how much of a burden Eurasianism and politics are for him as a brake on his scholarly activity. But on the other hand we must not allow this completely unpublic-spirited man to put a brake on the work of Eurasianism. In my opinion there can be no question of any kind of ‘bans’ on the paper by Trubetskoy, nor of a kurultai [Eurasian council of state] to wind it up. We must accept the challenge and sever the diseased member (luckily not the prick, as it happens).

The conclusion of Mirsky’s argument is outrageous, and typically maximalist: he urges that two of the pillars of the movement be expelled from it:

Meanwhile, this incident demonstrates that the present organizational system of Eurasianism (‘the ‘group of five’) is completely unsatisfactory. It is essential to ‘democratize’ Eurasianism, to make it into a party … [We] need a big congress, with the central committee + representatives of the local organizations. There is no need to chase after representation from the USSR (which will in fact be representation by the GPU). The congress must be public (or at least open) and be of an agitational nature. The only alternative is a retreat to intelligentsia positions, turning [the movement] into a purely ideological circle, but even in that case it’s essential to distinguish it from the underground. But the thing I do insist on unconditionally is the immediate expulsion of Trubetskoy and Savitsky from Eurasianism, unless of course they submit unconditionally. But any more negotiations with them are impermissible. I understand that this break will be painful for you, but it’s essential, for otherwise Eurasianism is doomed to rot alive. (Each of us rotting individually is enough.) We must acknowledge the position that has already been created (and created by you). Eurasianism is you and the Paris group. There is nothing else worth talking about.

’ARE WE TRYING TO INFLUENCE STALIN?’

The seventh issue of Eurasia, published on 5 January 1929, carried Trubetskoy’s letter stating that he was leaving the editorial board and the Eurasian movement as a whole. From the tenth issue onwards the newspaper has an increasingly perfunctory feel. It may eventually become possible to establish the authorship of the anonymous articles and those signed by otherwise unknown persons and, in particular, to establish whether or not any of these pieces came from Soviet sources. The letters to Suvchinsky make it clear that even Mirsky did not know who had written some of these items. They are for the most quite unreadable; hindsight makes them risibly wide of the mark as the pointers to the future they were intended to be – even before Marxist inevitability entered the scene.

The unsigned leaders spelled out an increasingly hard pro-Stalin line, especially in discussing the left-wing and other deviations that had recently rocked the Soviet political boat. A series of anonymous articles on ‘The Problem of Ideocracy’ began in No. 12, published on 9 February 1929, and went on and on; as we shall see, these articles were written by Suvchinskyi, and subjected to increasingly harsh criticism by Mirsky in his eltters. The summaries of economic developments and the reports of what was going on in the USSR at the time, though, retain some interest since they manage to maintain a critical edge.

The single fresh voice to appear was that of the only woman to have made a serious contribution to Eurasianism, and then, as we see now, when it was staggering towards its demise: this was Mirsky’s protégée Emiliya Emmanuilovna Litauer, who contributed an extensive series of reviews on philosophical topics. They began with a piece on Heidegger’s Sein und Zeit in No. 2 and went on to tackle some more of the most serious publications in current Continental philosophy; this is technical philosophy on a high level of competence, and it contrasts strongly with the woolly ‘philosophizing’ of such as Karsavin and Suvchinsky.

The latter issues of Eurasia did succeed in attracting some advertising, which to the mentality of seventy years later is much more attractive as literary text than the ponderous articles that precede it. The advertisements tout the services of various Russian-speaking lawyers and doctors in Paris, along with some tailors and oculists; as always, the patent medicines are the most arresting items on offer.

On 26 January 1929 Mirsky informed Suvchinsky that he was so busy writing a big book – he was referring to Russia: A Social History – that he now had too little time to write serious articles for Eurasia. On 13 March 1919 Mirsky tried again for a showdown with Suvchinsky:

When I come over I want to confront directly the question of what we’re doing and what we want. It’s not a matter of the content of Eurasianism, but the way it impinges on real life. Do we anticipate taking power? Are we educating a younger generation? Are we addressing problems that are of general use for anybody besides ourselves? Are we trying to influence Stalin?

The file that was kept on Mirsky after his arrest states that on 24 April 1929 he took part in a meeting of the Eurasian Council; but what transpired has not been discovered so far. On 14 May 1929 Mirsky wrote one of his most peremptory letters to Suvchinsky, treating him now almost like a child. This is the ultimate example of Mirsky’s ‘numbered points’ procedure. He is reacting to the draft of an article, and begins by objecting to the way Suvchinsky makes his philosophy too overt. This is the beginning of a sustained assault:

Secondly, I object to your manner of philosophizing; in the articles about ideocracy, you’ve started writing without knowing how you were going to finish. You’ve been doing your thinking in public. This spadework should be done in private behind closed doors (in the bog, maybe). Thirdly, the philosophical part must be either a) immediately comprehensible, or b) if that is not possible, it must be written in absolutely precise and sustained terminology, and that terminology must be as far as possible 1) uniform, 2) avoid phenomenological language, which is alien to us, and stay close to Hegel, 3) when a new term or one that is not generally understood is introduced, a precise definition must be given immediately (which in the case of new concepts will even precede the appearance of the term itself, thus: this is what we call this process (or these facts)); for example, it took me a long time to understand in which of very many senses you were using the word ‘anthropology’, 4) if a concept is not absolutely new, then you shouldn’t dream up a new word for it, 5) the main thing is to stay completely away from unusual words that do not have an absolutely precise meaning.

In August 1929 Mirsky’s biography of Lenin was commissioned, and he set to work on the reading that would, as he soon asserted, redefine and clarify his entire attitude, leaving all half-way houses behind. On 1 September he peremptorily told Suvchinsky that with Efron and Rodzevich he had decided to close the newspaper after the next issue. He also emphasized that there was no further reason for him to stay in the same organization as Malevich. It took the rest of the year for the affairs of the newspaper to be wound up.

By the time the newspaper closed, Mirsky had published about forty separate items in it. Not surprisingly, his original role was that of the leading spokesman on literature and culture. His first two contributions appeared together in the back pages of the first issue. One of them is an essay on Tolstoy, a pendant to the magnificent articles in English of 1928, the centenary of Tolstoy’s birth, and it concludes with the noblest declaration of his sense of personal ethics that Mirsky ever set down. His familiar emphasis on the creative will is replaced here by a stress on the ethical implications of the passivity he could not tolerate:

Tolstoy’s prophetic inspiration was eventually more powerful than the commandments he invented. We do not believe him when he says that to serve the cause of social justice it is better to do nothing. But the fact that each one of us bears within ourselves responsibility for present untruth; that not a single one of our submissions to this untruth is morally indifferent; that he who is not with the truth is against it, and that there can be no neutrality in this argument; that the first obligation of a man and a Christian is his obligation towards the community of his brothers; than any wealth of the one is founded on the poverty of others, and is therefore criminal and ought to be abolished – all this remains true, and it was all said by Tolstoy more loudly, more powerfully, and more pitilessly than by anybody else, and Tolstoy will always remain the Teacher.35

The second item by Mirsky in this first issue, though, contrasts strangely with the ringing confidence of the piece on Tolstoy. It is a review of the younger Soviet poet Bagritsky’s collection The South-West, an dis crushed in small type onto the back page underneath Tsvetaeva’s greeting. Mirsky singles out and cites one poem from the book as ‘not only one of the best lyric poems of the post-revolutionary period, but one that both in terms of its theme and its tone must necessarily be very close for many men of our generation’:

Against black breath and faithful wife

We’ve been inoculated by greensickness.

Our years have been tried by hoof and stone,

Our fluids suffused with evergreen wormwood.—

Wormwood that’s bitter upon our liops …36

Mirsky supplied some more pieces to Eurasia on literary subjects as 1929 went on, none of them up to his highest standards except for two, which discuss Khlebnikov and Chekhov.37 There are two articles, again characteristically on rising Soviet authors – one on Nikolay Tikhonov and the other called ‘Prose by Poets’, one of his old warhorses. There is also what became almost the final word Mirsky published about Russian émigré literature; his opinion corresponds very closely to what he said on the same topic for Slavisch Rundschau. And there is another interesting piece on literature and cinema.38

Mirsky contributed his most significant articles to Eurasia on non-literary subjects. They are the most explicitly pro-Soviet items in the newspaper. Mirsky’s largest contribution was a doggedly factual thirteen-part series on ‘The Nationalities of the USSR’. It reads in fact like a translation of the appropriate parts of his Russia: A Social History. In a series of purely political articles Mirsky contributed between January and March 1929 he speaks explicitly as a Eurasian, examining the compatibility of Marxist and other ideas with the standpoint of the movement. They begin with ‘The Proletariat and the Idea of Class’ on 19 January, continue with ‘Our Marxism’ on 2 February, ‘Three Theses on Ideocracy’ on 9 February, ‘The Problem of the Difference between Russia and Europe’ on 23 February, and culminate with a three-part discussion of ‘The Social Nature of Russian Power’ that ran to the end of March. In these articles, Mirsky essentially redefines Eurasianism in the spirit of his nascent Marxism; the end result is to present the case that there is no further justification for the independent existence of Eurasianism itself.

The schism in the Eurasian movement, and the political articles Mirsky contributed to the newspaper in 1929, it goes without saying, related to the contemporary events in Russia and elsewhere that made this year a turning-point. In Russia, Stalin decisively consolidated his power. In 1927, he had eliminated the Left Opposition – Trotsky and his followers. In 1928 he conducted the elimination of the Right Opposition, the comrades who had supported him against Trotsky – chief among them Kamenev and Zinoviev, who were soon followed by Bukharin, Rykov, and Tomsky. Stalin then brought back Radek, Zinoviev, and Kamenev, humiliated and cowed. In December 1928 the extension of Soviet power to the countryside, the brutal anti-kulak campaign, began. On the industrial front, the Shakhty trial was mounted at the same time. In February 1929, Trotsky was expelled from the USSR. The collectivization of agriculture and the first Five-Year Plan were pushed ahead. Elsewhere in Europe, the first triumphal Nazi rally was held in Nuremberg as the party’s elected representation rose in the Reichstag; the British parliament acquired a precarious Labour majority;39 and in the USA, on ‘Black Thursday’, 24 October 1929, the New York stock market collapsed. On 17 October 1929 Mirsky ended a letter to Suvchinsky with an eloquent sentence: ‘In my room are installed as the only decorations a World Map (published by Moscow Worker Press) and a portrait of Stalin looking at it.’

On 31 October 1929 Mirsky wrote Suvchinsky what is essentially his farewell to Eurasianism, a letter also tantamount to a farewell to Suvchinsky as a serious ally. The disenchanted attitude towards the USSR here is particularly remarkable; Mirsky had no illusions whatsoever about the way he and the others were viewed by the Soviet authorities. He thinks about his own possible contribution in terms of service, as a subordinate working to external command:

[The] authorities will never agree to let in a group of people who wish to develop a new ideology … [As] a group we can be useful only through what we do here. Only here can we retain the external independence that alone can give us some kind of authority. Over there we can work only as individuals, and then only if we entirely and unconditionally enter the orbit of the C[ommunity] P[arty] (which I personally would agree to do, but I shan’t go there for a long time yet because I think there’s a greater need for me here, if I’m needed at all)… As far as I’m concerned, the ideology of Eurasianism was only a means, a working hypothesis, which has no fulfilled its function. I’ve said all this (approximately) to Arapov too, and he accuses me of defeatism, aber ich kann nicht anders.

In his next paragraph, Mirsky unwittingly foretells his own personal fate; ‘to be sent to places far removed’ was the Tsarist administration’s language for internal exile, and it persisted into the Soviet period:

Going back to practical matters, and once again absolutely condemning the idea of transferring to the Union, at the same time I would very much welcome it if you made a trip there, with Arapov or without. With your well-known ability to butter up and charm people, such a trip might bring good results. But of course one can only consider this if there is a favorable solution to our practice problems. Any kind of transition from visit to residence will of course end badly, most likely of all in places more or less far removed.

Mirsky goes on to dismiss the course he was shortly to take:

One could still think about Gorky, but you understand of course that a connection with Gorky can only come about as a result of the liquidation of organized Eurasianism and a transition to a broad alliance of non-party Leninist-Stalinists. I would welcome an alliance of that kind, of course, and there is a place in it for us. But in practice I don’t believe in it. Everything that has ever been done on Gorky’s initiative has always been afflicted with sterility.

On 11 November 1929 he told Suvchinsky: ‘I’m writing to you just after finishing the Leader’s October article.40 I’ll read the rest of it on the way to Oxford, where I’m going with Arapov to give a lecture.’ This was the occasion when Mirsky was observed by Isaiah Berlin, who gave me a completely different account of what went on that evening from the published account of the meeting. The report in the Oxford Magazine summarizes a familiar line of Mirsky’s about Pushkin’s non-metaphorical style; Berlin, however, insisted that Mirsky was drunk and incapable of coherent speech and thought.41

This was probably one of the occasions on which Mirsky stayed with the Spaldings; in the words of the daughter of the family: ‘In those days we lived in Shotover outside Oxford and I seem to remember that Prince Mirsky mostly stayed in a cottage, then called Domic [Russian domik, ‘little house’], with the Narishkins at the bottom of our garden.’ This may have been the same visit Miss Spalding was speaking about when she said: ‘I certainly remember my parents being much put out when they had invited a number of people to tea to hear, as they expected, Prince Mirsky talking along White Russian lines, to find that over night he had turned Red.’42

MIRSKY’S MARXISM

Mirsky actually proclaimed himself a committed Communist in a letter written to Suvchinsky from London two days after the trip with Arapov to Oxford, on 13 November 1929. Two years later he published an account of how his conversion came about. It points to several factors that influenced his decision. In particular, Mirsky named three living men who played a part in converting him to Marxism. Two of them were Russians. The first, as we might expect, was Gorky, whose ‘Marxism’ was of an extremely peculiar kind, indistinguishable in fact from Nietzscheanism. The second was the historian M.N. Pokrovsky, whose work Mirsky translated, as we have seen. The third was an Englishman, Maurice Dobb (1900-76), lecturer in economics at the University of Cambridge from 1924, and a founder member of the Communist Party of Great Britain in 1920. In Mirsky’s reference to Dobb, the use of the word ‘realities’ is piquant:

The third source of help was a growing acquaintance with Soviet realities – especially with the great economic achievement of the period of recovery. Maurice Dobb’s Economic Developments in Soviet Russia was of particular assistance. It made me finally understand that the Nep was not transforming Russia into a peasant bourgeois community, but was indeed heading towards Socialism.43

On 11 November 1929 in London, after watching Battleship Potemkin, Mirsky met Eisenstein and Aleksandrov,44 and with the latter, as he told Suvchinsky, he had ‘a long and interesting conversation – he spoke about Soviet construction, the state farms, and all this in such an encouraging spirit (very concrete) that I was even more confirmed in the general line’. Mirsky’s next letter to Suvchinsky, written on 13 November, is characteristically categorical:

Workers of the World, Unite!

That Marxism is correct as a theory of history is for me not conditional but absolute. … I assert the absolute value of Marxism as a historian, and this is my considered and tested conviction, formed precisely through the study of precapitalist periods. The only matter in which I do not go along with current Marxism is that I do not draw conclusions of a metaphysical nature from the absolute correctness of historical materialism.

The last letter to Suvchinsky of the intensive series that began when Mirsky became seriously involved with Eurasianism in 1926 was written on 22 January 1930. Mirsky tells his friend that he has got down to writing his biography of Lenin. To judge from the remainder of the letter, nothing untoward had happened between the two men. But there was then a sixteen-month break in the correspondence, at least from Mirsky’s side; he next wrote to Suvchinsky on 21 May 1931. What went on in the interval is impossible to reconstruct in any detail on the basis of the evidence currently available. Mirsky had nothing further to do with organized Eurasianism, except to pour scorn on it in his account of his conversion to Marxism. But it was in April 1930 that relations between Mirsky and Suvchinsky’s wife, Vera, reached a crisis, and the break with Suvchinsky doubtless had something to do with this.