by Kidder Smith

Tricycle

Summer 2001

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

-- A Zen Nazi in Wartime Japan: Count Dürckheim and his Sources—D.T. Suzuki, Yasutani Haku’un and Eugen Herrigel, by Brian Victoria

-- Buddhism and Disasters: From World War II to Fukushima, by Brian Victoria

-- Corporate Zen in Postwar Japan, Chapter Eleven, [Excerpt] from "Zen at War", by Brian Daizen Victoria

-- D.T. Suzuki, Zen and the Nazis, by Brian Daizen Victoria

-- Other Zen Masters and Scholars in the War Effort, Chapter Nine, [Excerpt] from "Zen at War", by Brian Daizen Victoria

-- The Emergence of Imperial-State Zen and Soldier Zen [Chapter Eight], [Excerpt] from "Zen at War", by Brian Daizen Victoria

-- The Formation and Principles of Count Dürckheim’s Nazi Worldview and his interpretation of Japanese Spirit and Zen, by Karl Baier

-- The Postwar Zen Responses to Imperial-Way Buddhism, Imperial-State Zen, and Soldier, Zen, Chapter Ten, [Excerpt] from "Zen at War", by Brian Daizen Victoria

-- Was It Buddhism? Chapter Twelve, [Excerpt] from "Zen at War", by Brian Daizen Victoria

-- Zen as a Cult of Death in the Wartime Writings of D.T. Suzuki, by Brian Victoria

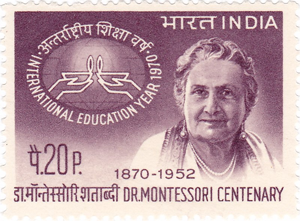

The author’s great-grandfather, Wilbur Eliot Wilder, who began a family lineage of military involvement © Kidder Smith

It was an unanticipated homecoming for me, addressing a West Point audience on military matters a few years ago. My original connection to the United States Military Academy runs through my great-grandfather, class of ’77, who’d gone on to win the Congressional Medal of Honor for action against a Native American uprising in the Southwest. His son, my grandfather, graduated from the Academy in 1907; his only son, my uncle, went from Harvard to military intelligence in Korea, and from there to the CIA. But I became Buddhist soon after leaving high school, and I graduated from college as a conscientious objector, refusing the draft because of religious opposition to war of any kind. Yet, paradoxically, it was Buddhism that brought me back to West Point.

In 1975 I began studying with Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, a Tibetan meditation master who, in addition to retreats, schools, and monasteries, had his own military organization. This was the Dorje Kasung, or Vajra Guard, a group based on Buddhist principles of nonaggression—no one was armed, and we didn’t even practice the martial arts. Instead, this military was a means by which Trungpa Rinpoche taught dharma to a self-selected subset of students.

The very notion of a Buddhist military is itself rife with paradox. Yet this is an army whose aim is victory over aggression, rather than victory through warfare. Its fundamental principles respect the Buddhist precept against taking life, but they also respect all people and things. Instead of focusing on combat, then, this army is a form of Buddhist practice. Like all Buddhist practice, it is a form of mind training.

The Boulder guru keeps a household protection squad, known as the Vajra Guard. They are the Beefeaters of Buddhism. When the guru goes out in public, so do they. (In between times, they meditate.) The rumor is, they're armed with M-16's. Others say it's submachine guns....

Q. You've said you've lately been pretty upset over this whole issue. Did you go to see Trungpa specifically because of this?

[Allen Ginsberg] Well, I was blowing my top a few weeks ago, so I went to see him. I said, "What happens if you ask me to kill Merwin?" That was my idea.

Q. You shouldn't put ideas in his head.

A. It was in my head, so why shouldn't I? I mean, the whole point is that that's precisely what you should consider.

Q. If you make a test out of it--

A. Ah.

Q. Was he reassuring?

A. Yeah. Well, he was somewhat reassuring. He was sitting there really sweet, actually. I'd gone to see this monster.

Q. This what?

A. Well, I'd built up this monster in my head. And he explained what -- "I was just talking about my roots, with Dana." But I'd built up this monster. That was my paranoia, the kind that builds up in precisely this kind of situation.

Q. So rather than dispel that situation by making a clear statement on it to his disciples, he feels that they should just work their way through it by themselves?

A. No. When I went to see him I asked him exactly that question. You see, the nature of the teaching and the teaching methods is such that it's very hard. How do you talk about Vajrayana teachings in public? It's very hard to do. And it's made even more difficult by the American situation, where everything is slowly coming out anyway.

Q. Undoubtedly all this is coming out.

A. The point I guess that most struck me was -- you see, Merwin was free to leave or free to stay. Trungpa encouraged him to stay, and went out of his way to put himself in danger, in a sense. So I don't know what the rights and wrongs of it are, but I find more and more my consideration of it is not so much that Trungpa was wrong, but that he was indiscreet. So I say to myself, he was indiscreet. And then I realize what a shitty viewpoint that is. You know, that's a political viewpoint. And you know, the worst charge I have against him is he was indiscreet, and put me in a situation where I have to be here and explain it and go through all of this scandal. As if I haven't had enough with L.S.D. and enough with fag liberation, now I've got to go through Vajrayana, and pretty soon they're going to have articles in Harpers by idiotic poets that I never hired to begin with! About Merwin whose poetry I don't care about anyway! With Ed Sanders freaking out and saying it's another Manson case! Because Ed's paranoia, actually -- Ed has a large quotient of paranoia too. Anything that reminds him of secrecy -- he's been all his life studying black magic and Aleister Crowley and playing around with all that on the sidelines. I mean, getting into the Manson thing, and then getting into Vajrayana and Trungpa and Merwin, is just sort of made for Ed Sanders. And all of Ed's paranoia. And it's made for my paranoia, because half the time I think, "maybe Trungpa's the C.I.A., and he's taking over my mind." Much less all the poets, who want the supreme egotism of poetry -- that poetry should be the supreme individualistic reference point, that nobody should be above the poets, and that if anybody is they'll get the American Civil liberties Union after them! The poets have a right to shit on anybody they want to. You know, the poets have got the divine right of poetry. They go around, you know, commit suicide. Burroughs commits murder, Gregory Corso borrows money from everybody and shoots up drugs for twenty years, but he's "divine Gregory." But poor old Trungpa, who's been suffering since he was two years old to teach the dharma, isn't allowed to wave his frankfurter! And if he does, the poets get real mad that their territory is being invaded!

And then I'm supposed to be like the diplomat poet, defending poetry against those horrible alien gooks with their weird Himalayan practices. And American culture! "How dare you criticize American culture!" Everybody's been criticizing it for twenty years, prophesizing the doom of America, how rotten America is. And Burroughs is talking about, "democracy, shit! What we need is a new Hitler." Democracy, nothing! They exploded the atom bomb without asking us. Everybody's defending American democracy. American democracy's this thing, this Oothoon. The last civilized refuge of the world -- after twenty years of denouncing it as the pits! You know, so now it's the 1970's, everyone wants to go back and say, "Oh, no, we've got it comfortable. Here are these people invading us with their mind control."

And particularly, most particularly, people who suck up to Castro and Mao Tse-Tung. That's the funniest part. All the people, even myself who'd had all sorts of hideous experiences with Marxism. Or who put up with Leroi Jones. It's never questioned, you'd never publicly question that -- write an article about Leroi Jones in Harpers! You know, pointing out the contradictions in his democratic thought. Or anybody's, for that matter.

So, yes, it is true that Trungpa is questioning the very foundations of American democracy. Absolutely. And pointing out that the whole -- for one thing, he's an atheist. So he's pointing out that "In God we trust" is printed on the money. And that "we were endowed with certain inalienable rights, including life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness." That Merwin has been endowed by his creator with certain inalienable rights, including life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Trungpa is asking if there's any deeper axiomatic basis than some creator coming along and guaranteeing his rights.

Because one of the interesting things that the Buddhists point out is that there's always a sneaking God around somewhere, putting down these inalienable rights. Urizen is around somewhere. And they're having to deal not only with the Communists, and the fascists, and the capitalists, they also have to deal with the whole notion of God, which is built right into the Bill of Rights. The whole foundation of American democracy is built on that, and it's as full of holes as Swiss cheese.....

Q. You read for us some of the poems to the aggressive deities, the ones Merwin didn't like. They had lines like, "as night falls, you cut the aorta of the perverter of the teachings," and "you enjoy drinking the hot blood of the ego."

A. Right. So he didn't like "drink the hot blood of the ego."

Q. Or, "cut the aorta of the perverter of the teachings"?

A. That would be Chogyam Trungpa if he was perverting the teachings.

Q. Trungpa would get his aorta cut?

A. Well, the aorta's the life-blood.

Q. So that's just metaphorical?

A. Oh, I suppose so. You might take it literally. Who knows. If I were Burroughs I would say, "of course it's literal."

-- The Great Naropa Poetry Wars, With a Copious Collection of Germane Documents Assembled by the Author, by Tom Clark

It was a flowering such as had never been seen before. Naropa University opened its doors. Every major city in the United States and Europe had a Vajradhatu meditation center and ambassadors were sent out from the Court of Shambhala. When the Prince gripped my arm for support he guided me through the halls, streets, and airports. His step was sure and firm. It was as if I were the crippled one instead of him. The Court was filled with activity.

In one week I had a schedule of over 150 volunteer servants: guards, drivers, cooks, cleaners, nannies, gardeners, servers, secretaries, shoppers, and waiters. All were wanting to participate in the flowering energy that filled the Court, which made it indeed seem to stretch over several miles with a park in the center on the top of a great circular mountain. What had been created was an openness where everything could be explored. We were encouraged to practice, study, and investigate our inner and outer worlds and examine any resulting pain or pleasure.

In the midst of this creative turmoil the Prince challenged me on my military propensities with a casual remark made into the bathroom mirror one morning.

"When we take over Nova Scotia, Johnny, you will need to attack some of the small military bases there."

''Attack military bases!" I said with surprise. "Me?"

"Well, not alone," smiled the Prince, still looking into the mirror examining his freshly brushed teeth. "You could have a commando unit of Jeeps and halftracks." He was looking at me in the mirror as he continued, "You had a halftrack once, didn't you?"

"Yes," I replied, remembering the olive drab army vehicle I owned at the farming school I once ran, seemingly a hundred years ago.

"Well?" the Prince's voice sounded.

My mind activated like a World War II movie as our intrepid band in Jeeps and halftracks raced along the curved snake-like back roads of Nova Scotia toward the unsuspecting enemy. My khaki wool uniform blended with the green countryside, I gripped the metal frame of the Thompson machine gun in my capable hands. On my head was the red beret bearing the Trident badge and the motto "Victory Over War." I smelled the engine oil fumes mixing with the flower perfumes of the country lane as we whipped along on our desperate mission. The sun glinted on our bayonets, or wait, perhaps it was night ...

"Well?" asked the Prince again.

"Oh, oh," was the reply, as I returned from the battle to the bathroom. "Yes, yes, Sir," I said. "We could do that."

"Good," continued the Prince. "You might have to kill one or two.

Kill one or two? What's that mean-kill one or two? was my silent response.

"But I thought we are not supposed to kill," I said, somewhat alarmed.

"Just a few resisters," said the Prince.

Resister, what the fuck is a resister? ran through my mind. Out loud I asked, "Resister? What kind of a resister?"

"Someone may resist enlightenment," stated the Prince.

"Oh, those. Well, yes, we could take care of them," I reassured him.

"Good, good," said the Prince, turning to leave the bathroom. As he opened the door he concluded with, "Well, Major Perks, perhaps you could put all of that together."

I spent the next several hours studying Army surplus catalogs and The Shotgun News. At the local gun store I picked up copies of Commando and SAS Training Manuals. I made a list of equipment and concluded that this "invasion" was going to be costly. I went to the Prince.

"Where will we get the money to organize this armed commando force, Sir?" I said, almost saluting.

"Perhaps we could steal the equipment," he suggested.

"Wow," I exclaimed. "You mean like a covert operation." The words and idea thrilled me.

"Exactly," said the Prince. ''And we need a code name for it." He contemplated for a moment and then said, "How about Operation Deep Cut?" As I turned the words over in my mind he continued, "Yes, what is needed here is a surgical strike."

I excitedly repeated the code name, "Operation Deep Cut, covert operation Surgical Strike." This was going to be worth killing just one or two!

"Yes," said the Prince with delight. "Buy some books on tactics and strategy. We should all study them. And you, Major Perks, will be in command." I could hardly wait to take my leave and get started on the campaign. I put on my military hat, saluted the Prince, and ran out of the room, tripping and falling down half the stairs in my haste. The Prince's head popped out of his sitting room doorway. ''Are you okay, Major?" he called down to me.

"Yes, Sir, fine, Sir. I just missed a step," I replied, pulling my uniform straight.

"Good," he said. "Jolly good, jolly, jolly good. Carry on, Major." I saluted again and rushed down the remaining stairs.

I could not wait to tell the other officers in the military about my secret mission. They were all amazed. "Have you told David yet?" was Jim's response. "Not yet," I replied. David was the Head of the Military, now that Jerry had dropped out. I could not fathom why the Prince had chosen David for this position. David was a very unmilitary, slight of build, a Jewish intellectual. He looked more like Mr. Peepers in a uniform -- nothing like Montgomery or Patton.

"I bet his balls shrivel up like raisins when I tell him about this," I scoffed. Indeed, David was quite alarmed at my description of "killing one or two resisters."

"Let me talk to Rinpoche before you do anything," he said anxiously, falling back in his chair.

"Okay," I said, adding with a tone of command, "go ahead, but it's all set. The Prince said so."

Later the Prince called me into his sitting room. I explained that David seemed hesitant about killing a few resisters.

"Oh, he's such a Jewish intellectual," said the Prince.

"Why, that's exactly what I think," I agreed.

"Really?" said the Prince, looking at me with curiosity. "Good, jolly good. You carry on, Major. I'll take care of David and tell him you have a free hand." I left hurriedly to tell the other officers the latest news on my secret commando operation....

Lady Diana, the Prince's wife, had confiscated his Scottish Eliot Clan kilt some months back because she felt he did not look good in Scottish regalia. It was rumored that the missing kilt was hidden at the mother-in-law's house.

"What we need is a practice run," said the Prince to me one morning. "Major, here's a job for your new commando group. We will invite Diana and my in-laws to the Court for dinner and while everyone is here your group will retrieve my kilt."

I saluted with a very big "Yes, Sir" and ran off to inform my comrades-in-arms.

The mother-in-law's house was situated in a small field near the edge of town. On the night in question we waited in our darkened limousine on a side road by the Court. There were four of us, dressed in black. We watched in nervous excitement as the mother-in-law's car pulled up to the Court. and the occupants entered the building. "Let's go," I commanded in a hushed military tone, and the driver sped toward our goal. Near the house he shut off the headlights and silently rolled to a stop in the shadows. We rolled out into the grass ditch and crawled on our bellies across the lawn. I pushed at one of the dining room windows. It opened and I was halfway through when Walter hissed, "The front door is open."

It was too late, however, as I was already pinned in the open window frame by the top window which had slid down on my back. My legs were dangling outside and my arms and head were inside the dining room. The others entered the dark house in a more upright fashion and hauled me through by yanking on my arms....

Triumphantly we returned to the Court. Dinner was finished and dessert was about to be served. I placed the kilt on a silver tray and presented it to the Prince and the seated guests. Lady Diana cried out laughingly "Oh no, Darling" to the Prince, who beamed and gave me the thumbs up sign. The other guests were delightedly amused.

In the following weeks we undertook other commando operations with odd code names: Operation Awake, Operation Blue Pancake, Operation Secret Mind, and Operation Snow White. "Why Snow White?" I asked the Prince. "Because she has to be woken up," was the reply. That made no sense to me. Why did you need to wake up a military operation when we were already totally awake and combat ready? I labeled the answer as crazy and added it to the collection.

During this time I started to have flashbacks to my childhood during the war. I had dreams of the bombing, the bodies in the yellow shrouds, the news footage of concentration camps. I began to feel confused about which was real, my remembrances of things past, the present military operations and the Court, or the future takeover of Nova Scotia. My uneasy feelings returned as did the panic attacks.

I did the same old stuff to avoid confronting any of it. I immersed myself in work, sex, entertainment, alcohol, and food. I knew I was okay, if only I could get myself together. I poured out my woes to the Prince, who was no help. In fact, he did not seem to understand at all and was quite unsympathetic. The more I freaked out the more demands he made on me....

"How are things going for the military encampment?" he asked....

-- The Mahasiddha and His Idiot Servant, by John Riley Perks

This year of building the kingdom:

Dealing with the four seasons,

Studying how millet grows

And how the birds form their eggs;

Interested in studying how Tampax are made,

And how furniture can be gold-leafed;

Studying the construction of my home,

How the whitewash of the plain wood can be dignified,

How we could develop terry cloth on our floor,

How my dapons can shoot accurately

-- First Thought Best Thought, 108 Poems, by Chogyam Trungpa

Trungpa Rinpoche was born in eastern Tibet in about 1939 and came to America by way of Oxford University, in 1970. He established a series of meditation centers across the United States and Europe and founded Naropa Institute (now Naropa University) in Boulder, Colorado. Though he died in 1987, the institutions he founded still flourish today under the direction of Shambhala International, based in Halifax, Nova Scotia. His students have been in many ways a conventional church group—people who hold day jobs and share variously in the community’s religious activities, keeping the books, maintaining the mailing list, teaching or taking a class at a local center, doing a solo meditation retreat. Some might also participate in the military, wearing blue blazers and gray skirts or trousers as they drive visiting Tibetan monks to the airport, escort a teacher to a talk, or act as security guards at public events. Here their practice has been the basic firmness of good manners, rooted in alertness and thoughtfulness, ready to say “No, you may not” or “Of course I will.” As such, it is an extension of training in mindfulness, awareness, and kindness, from which also arises the confidence to resist being pulled away from one’s center.

Many of us were doubtless working through difficult relationships with power and hierarchy—why else had we been drawn to this military?

Since the late 1970s members of this military have been invited to apply for a week-long summer encampment held in the Colorado Rockies or the hills of rural Nova Scotia. About eighty of us attended in any year. The style of practice combined monasticism with a boy—or girl-scout outing: khaki uniforms where one would traditionally find robes, individual pup tents in the place of cells, bugles or bagpipes instead of church bells, and drilling in formation in addition to more traditional forms of contemplative practice.

My own motives for participating? The desire to get into the outdoors with good old friends and to satisfy my curiosity about this odd practice.

In early years we’d rise at 6:30, wash or shave in hand mirrors, eat breakfast from our mess kit, and sit in meditation—outdoors, on the ground, in our jungle boots—for an hour. One afternoon there was a wedding. Trungpa Rinpoche might give a talk in the evenings. Gradually, further Buddhist practice forms seeped through the encampment. In 1979 he introduced oryoki, the Zen style of eating from three nested bowls. Meals began with chants and were conducted in silence; formal hand gestures indicated when one wished more food. After eating, each soldier was served hot water with which to clean his or her bowls. Thus oryoki became our new mess kits. Later Shibata Sensei, a Japanese archery master, designed an outdoor shrine room for us, where the decorum of indoor meditation could flourish on the rugged earth.

But it was marching that distinguished the encampment from anyone’s previous experience of a meditation retreat or camping out in the woods. Much of the morning and afternoon, especially at first, was given over to the practice. It was real army drill. Our sergeant major was a white South African, trained in their army before becoming Buddhist and emigrating to North America. The physical movements, the commands, and our responses were as close to that form as we could manage.

Only a few of us had had previous military experience, and at first we weren’t especially good at drill. I in particular had difficulty getting my arms to swing right—they were always too tight or too loose, too controlled and stiff or too woggly. As a college freshman I’d been inducted by my Chinese teacher into the local ballet school’s Christmas production, which had a chronic shortage of males. As “court dancer” I’d walked through simple steps with a beautiful costumed young woman on my arm. Drill was less romantic, but as I mimicked the steps, it rather resembled klutzy open-air ballet.

The tone, though, was different from both ballet school and the conventional military. The sergeant would yell at me (“Peas in a piss-pot” and other bits of nifty foreign military slang). But it was not possible for him to insult or demean me, to soil the place—his authority was transparent, fictive, created by our participation in this creation of our teacher. So I worked hard to make drill beautiful, sharp, and powerful. If I didn’t get it right, it really didn’t matter very much. And if I did get it right—which by the end of the week I had somewhat accomplished—it didn’t matter very much either. Each way was equally perfect within that vast space, that expanse, unstated, unstatable, of which the mountain atmosphere was a tiny simulacrum.

From that space, we Buddhists say, arises dance, thought, compassion, mind, everything. It was the experience of that huge space that particularly marked and defined our activity, that distinguished our drill from that of other military organizations. It was the container, and also the foundation, and also the inseparable nature of these forms that we practiced and thus transformed.

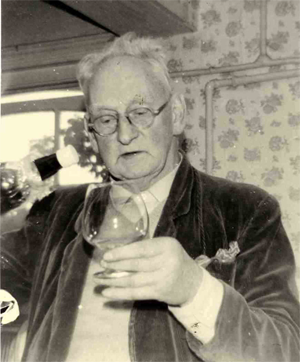

The author’s teacher, Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, created the Vajra Guard, an unarmed Buddhist military group, in the 1970s. He is seen here surveying an encampment

And in the process drill became meditation. Sharp attention to the details of physical movement. A clear awareness of the expanse around them. As with meditation on the breath, such movements defined our attention only in the moment, disappearing as they occurred. However demanding the details, they did not fully occupy our minds, which remained precisely focused and widely opened—at once alert and relaxed. And nothing was accomplished, except mind arising unobstructedly within our activity. Thus meditation in action.

One of my reactions was to feel grounded in simplicity, nothing to gain or lose. I recalled the image of Fudo, the fierce, enflamed Zen deity whose name means “unmoving”—unable to be thrown off my seat, I was fully connected but at the same time imperturbable. No one could fuck with me. Nor had I any wish to fuck with anyone. At the same time this certainly wasn’t my power, neither originating from, nor located in, any familiar sense of myself. It was rather a quality that had become publicly and generally available due to our practice. Bound by attention to the forms of practice, each of us, relinquishing smaller aims, discovered that self-existent field of power.

Another reaction was wonderment, as when something seeming solid shows its transparent nature and an unexpected vista falls open before you: the dearness of all creatures, rocks and earth, the huge life-force of the waterless highlands of our midcontinent. Accompanying this was a light and generous absurdity. As Trungpa Rinpoche put it in the slogan he bestowed on his military: “If you can maintain your sense of humor and a distrust of the rules laid down around you, there will be success.” Absurd, but also most precise and dignified, the unfolding of our dance, no star performers, only movement, mountains, the power of gestures, a naked ritual with no reference point outside itself.

And so the military forms of my forefathers were purified and transformed. In that moment aggression became superfluous, untenable—I had lost all inclination to it. Nor could traditional military hierarchy find a purchase on me. It was a first step toward victory over war.

In chapter 2, "Sources of Bushido." Nitobe clarified the relationship between Bushido and Zen as follows:I may begin with Buddhism. It furnished a sense of calm trust in Fate, a quiet submission to the inevitable, that stoic composure in sight of danger or calamity, that disdain of life and friendliness with death. A foremost teacher of swordsmanship, when he saw his pupil master the utmost of his art, told him, "Beyond this my instruction must give way to Zen teaching."3

Nitobe offered little detailed explanation of Zen teaching, but he did write that:[Zen's] method is contemplation, and its purport, so far as I understand it, [is] to be convinced of a principle that underlies all phenomena, and, if it can, of the Absolute itself, and thus to put oneself in harmony with this Absolute. Thus defined, the teaching was more than the dogma of a sect, and whoever attains to the perception of the Absolute rises above mundane things and awakes "to a new Heaven and a new Earth."4

-- The Emergence of Imperial-State Zen and Soldier Zen [Chapter Eight], [Excerpt] from "Zen at War", by Brian Daizen Victoria

One sunny afternoon our squad was policing the camp — thirty people in a single rank, double arms’ length apart, searching the ground for cigarette butts and trash. The officer in charge, somehow displeased, yelled that we’d have to do this all afternoon if we didn’t do it properly, to which we responded that it was such a beautiful day it would indeed be wonderful to do so.

That response wouldn’t work in most other environments, military or not. Aggression is plenty real, gritty and full of sorrow, all around us. And victory over war means learning how to work with all of it.

We’d rise at 6:30, wash or shave in hand mirrors, eat breakfast from our mess kit, and sit in meditation—outdoors, on the ground, in our jungle boots—for an hour.

How well did we do? We learned, sometimes, to spot parts of our aggression, loud and raw against this background of space, and let it pop with an embarrassed twitch, dissolve. But like that officer, we weren’t always able to tune into the generosity of something large beyond thinking. Many of us were doubtless working through difficult relationships with power and hierarchy—why else had we been drawn to this military? Encampment was physically inconvenient, and some city guys never got used to sleeping on the ground in their clothes. Combined mild irritants enhanced our basic ego-tendencies, strengthening our habitual patterns and sometimes reconverting those military forms we thought we had transmuted. On one occasion Trungpa Rinpoche reviewed the troops, each of us standing stiffly at attention beside our pup tent as he walked round the camp circle. Gathering us together just after, he remarked, “It makes me sad that none of you soldiers was brave enough to smile when I walked past.” Thus while encampment intensified our neurotic reactions, it also provided a space in which these distortions of our true nature became apparent to all.

Trungpa Rinpoche also found ways to heighten our paranoia, and then release it. In Colorado our entire water supply rested in a large, wheeled tanker, hauled up creaking from the valley below. I was on sentry duty late one sagebrush-scented night, when a shout rattled through the camp: someone had cut the tanker’s hose, and four days’ water had flowed away. Had anyone spotted a lurker? Was a saboteur concealed among us? The whole camp was roused, soldiers fell out in uniform and stood at attention, while busy officers sought intelligence from the groggy night. Orders came from somewhere for drill. Then we were before Trungpa Rinpoche, presenting ourselves one by one for interrogation. As I approached him, I was given a splosh of Tabasco in my palm to lick as a kind of truth-oath. Then in his Oxford-accented tenor he asked me, “Kidder, did you cut the hose?” “No, sir!” I replied, and gave him a wet kiss on the cheek. And eventually we were all back to bed.

At some point in that goofy midnight exercise it occurred to me that only one person would have enjoyed cutting the hose: Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche. It perfectly disrupted our normal sense of things, giving him and us the occasion for a joyful confusion, as soldiers sought earnestly for external enemies—a traitor? pranksters? militant pacifists?—only to find nothing there but the habits of our own mind. Still more, we met him eye to eye for a brief meditation interview, snatched out of our normal time for sleep. No perpetrator was ever identified, and nothing explained. It was left to each of us to figure out what had happened or to hear it from a friend, like the secret punch line of an intensely practical joke. And thus our paranoia was self-liberated.

Members of the Vajra Guard gather to celebrate the opening of a camp in the 1979s © Marvin Moore.

But other teaching situations demand other means. In the front lines of daily life, long after encampment ends, and long before it ever began, we are surrounded by great swirls of our own and others’ aggression. How to meet it? It’s essential to maintain forms of practice—forms of kindness and attention—so that our harmful impulses can find ways to be re-formed. I once asked a Buddhist friend why he thought Trungpa Rinpoche had instituted the military. “Well,” he said, “how would you work with X?”, naming someone widely regarded as an impossible asshole. Hence the creation of an institution that could accommodate not only someone like me, a mild-mannered college professor, in the full range of my X-rated manifestations, but that also possessed the widest emancipatory power, with practice forms capable of shaping people of varying temperaments, abilities, interests, even using an obsession with authority or violence as bait in the transformation of some men and women who might never bring dharma to their lives through any other means. But the military was much more than a means of working with the unworkable. It was a provocation of the full gamut of our karma, like tossing a vajra (Tibetan symbol of the indestructible and indivisible reality) into the aggressive heart of America.

There was no real Tibetan precedent for these military forms. Instead, they were Trungpa Rinpoche’s own response to the energy of this country, his reshaping of pieces of our past and present. What guides the teacher in his or her creation of form? Is there a set of ethical principles that might contain it? An early Indian text, the Digha Nikaya, offers a hint to why there isn’t. The following passage, from Wm. Theodore de Bary’s The Buddhist Tradition, describes the Buddha (referred to as “the monk Gautama”) in his relationship to five moral fields—taking life, theft, improper sexual relations, lies, and slander:

The monk Gautama has given up injury to life, he has lost all inclination to it; he has laid aside the cudgel and the sword, and he lives modestly, full of mercy, desiring in compassion the welfare of all things living.

He has given up taking what is not given, he has lost all inclination to it…

And so the text continues through sexual relations, lies, and slander.

He has lost all inclination. He desires in compassion. That’s all it says. There are no commandments or guarantees, no higher authority. The foundation of all Buddhist ethics, then, is only the propensities of Buddha-mind.

Ultimately this is your mind. Before we’re fully confident of this, though, before our own actions emerge unobstructedly from space, before we discover our own power to create form, how do we make choices? How do we decide if it’s good to join the military, or to follow our teacher’s commands? After all, the Tibetan Buddhist master is very much a guru, someone to whom the student in varying degrees entrusts his/her life. And this hierarchy can be as severe as that of any military.

There is no certainty within this relative truth, and we are stuck here several ways at once. We rely on our basic decency, yet we must also step out of habit. We learn to trust ourselves, yet we wonder if that self exists and how far it’s reliable. Our teacher is steeped in lovingkindness, but her compassion may sometimes seem opaque and therefore may not quite reach our hearts . From practice, we get hints of something hugely good, but in fragments. Gradually we may come to fully trust our guru, but how can we do this before we know his mind and ours is the same? This is relationship with a spiritual teacher. The military practice intensifies it, reminding us how much is at stake, and of the traditional efficacy and danger of the tantric path, which works not only with the milder forms of human life but also with the ungainly, the disturbing, with alcohol, sex, and, in this case, with raw aggression, turning that fierce energy into a means to free all beings.

Today I live in Maine, in a small town that shares its space with the vast and open runways of a naval air station. Among the moms and dads of my daughter’s friends are several military people with whom I feel a profound yet uncertain fellowship. I suspect that, like my great-grandfather, they may have found the American military ennobling. I wonder if it has also allowed them to purify their own aggression until, seeing through the disciplines of form, they can offer protection to all beings in need.

Kidder Smith teaches Chinese history at Bowdoin College, where he also directs the Asian Studies Program. He has written extensively on the military texts of ancient China and on issues of Buddhist practice.